Peer-review started: July 20, 2017

First decision: August 7, 2017

Revised: August 26, 2017

Accepted: October 15, 2017

Article in press: October 16, 2017

Published online: November 2, 2017

Processing time: 123 Days and 16.8 Hours

Homoxygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia is characterized by a presence of several types of cutaneous xanthomas with an abnormal lipid profile. Some of these could be pathognomonic. Although these could be initially interpreted as isolated and localized benign disorders and offered surgical treatment, it has become increasingly clear that they could be a part of a systemic pathology. Here we describe a case of this rare disorder in a 19 years old non-obese young man who presented multiple, intertriginous, tuberous and tendinous xanthomas and had an associated abnormal lipid profile with elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. A detailed history with clinical assessment in the differential diagnosis and laboratory investigations led to a precise diagnosis.

Core tip: This article describes a contemporary approach to the differential diagnosis of xanthomas, and the morphological classification from a review of the literature, specifically reflect the clinical findings evidenced in this case report.

- Citation: Mastrolorenzo A, D’Errico A, Pierotti P, Vannucchi M, Giannini S, Fossi F. Pleomorphic cutaneous xanthomas disclosing homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. World J Dermatol 2017; 6(4): 59-65

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6190/full/v6/i4/59.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5314/wjd.v6.i4.59

The clinical picture of xanthomas is variable from yellow or orange dermal macules or papules, to soft or firm-hard subcutaneous plaques and tendinous nodules not attached to underlying structures, with normal-appearing overlying skin. In recent years, interest in xanthomas has been growing for several reasons, mainly because the pathogenetic mechanisms involved in the development seems to be similar to those in early stages of atherosclerotic plaques[1]. Cholesterol accumulation in tissues produces common dermatological manifestations as several types of cutaneous xanthomas[2]. The association of xanthomas with lipoprotein disorders was initially defined by Frederickson’s classification[3,4]. From that phenotypic classification the recent advances in molecular genetics led to the discovery of a broad group of disorders of the lipids metabolism disclosing the relationship between the development of xanthomas and hyperlipidemias[1,5,6].

Xanthomas can be classified following clinical as well as patho-anatomical schemes, addressing special attention to the needs of dermatologists and internal medicine specialists respectively. These correlated issues gave rise to the following groups which are useful in clinical practice: Normolipidaemic xanthomas (NX), hyperlipidaemic xanthomas (HX), and necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG)[1,7,8]. Nevertheless, xanthomas may be seen either as a primary disorder (primary dyslipidemia, an inherited abnormality of lipoprotein metabolism) or secondary disorder (hyperlipidemia secondary to systemic disease or medication)[1,4,9].

Cutaneous xanthomas may or may not be present with lipid metabolic disorders, usually depending on the severity of the lipid abnormality. Normolipidemic xanthomas mostly appear as diffuse flat skin lesions, while hyperlipidaemic types are polymorphous, often tuberous, and can affect either skin or tendons and joints. Recognition of these types of xanthomas may be facilitated on the basis of clinical morphology, presence or absence of inflammation, anatomic distribution, and development pattern, defining the primary type of lesion and histologic level of involvement. From a dermatological point of view these can be categorized in two specific subsets and each one with distinctive clinical associated features: (1) papulonodular xanthomas: Eruptive and tubero-eruptive xanthoma, xanthoma tuberosum (the term “tuberous” refers to the nodular character of these xanthomas) and tendineum; and (2) plane xanthomas: Plane and intertriginous xanthoma, striated palmar xanthoma and xanthelasma palpebrarum[1,4,9-11].

We report a case of a young man with multiple pleomorphic cutaneous xanthomas in association with a neglected Homoxygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (HoFH). This article thus presents a contemporary approach to the differential diagnosis of xanthomas, and the diagnostic criteria we propose was developed after a review of the literature, and reflect the clinical findings evidenced in our patient, seen at our dermatological facility.

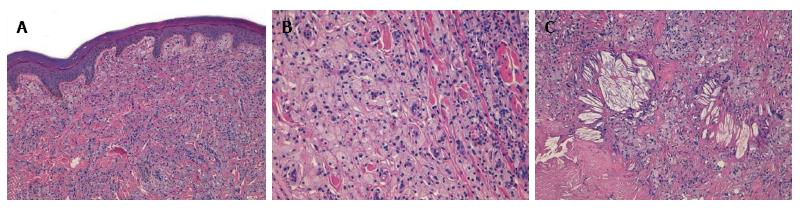

A 19 years old non-obese young man presented as an outpatient to our hospital with multiple, bilateral and symmetrical slow growing yellowish lesions of various forms over the dorsum of the elbows, knees, buttocks, ears, feet and hands. Biopsy of three representative and different skin lesions revealed them to be xanthomas characterized by the presence in the dermis of cholesterol crystalline aggregates surrounded by fibrosis and foamy cells (Figure 1).

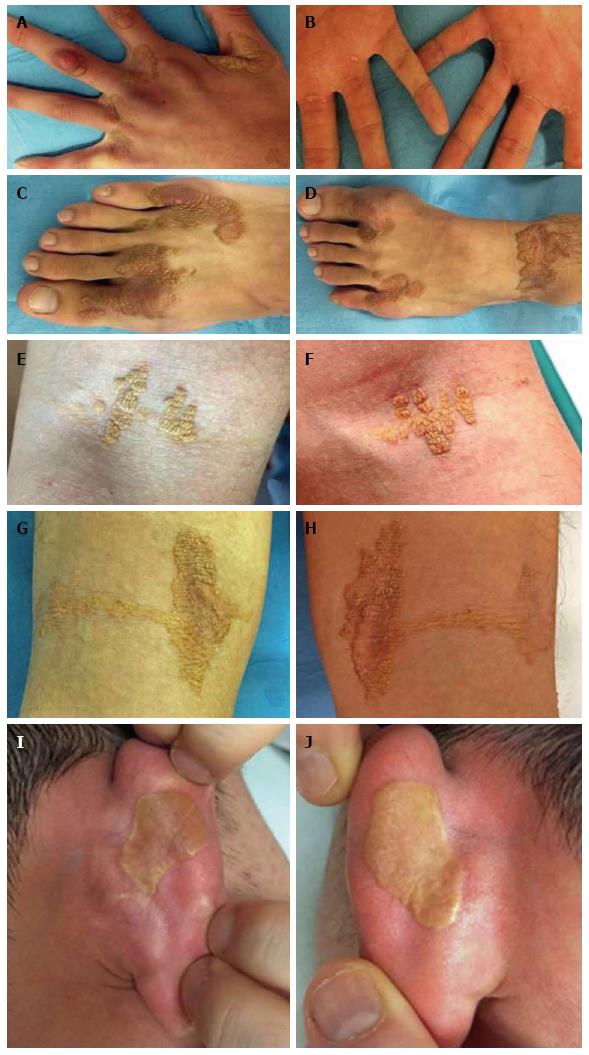

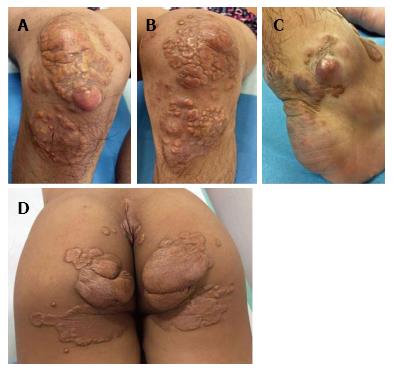

On dermatological examination each lesion was defined on morphological pattern. The following clinical forms have been recognized: (1) Xanthelasma: Involving the inner canthus of the left eye (Figure 2); (2) Intertriginous xanthomas and a confluence of plane-eruptive xanthomas (Figure 3): In finger web spaces (Figure 3A), toe web spaces (Figure 3C and D), and the flexural surfaces: the ankle crease (Figure 3D), the antecubital fossae (Figure 3E and F), the popliteal fossae (Figure 3G and H) and the creases of ears (Figure 3I and J); (3) Tendinous xanthomas (Figure 4): To form a single mass localized all over the Achilles tendon just above its insertion point to the calcaneal tuberosity; and (4) Tuberous xanthomas (Figure 5): Soft skin color or yellowish nodules and tumors, with a tendency to coalesce, localized on the knees (Figure 5A and B), malleolus (Figure 5C) and buttocks (Figure 5D).

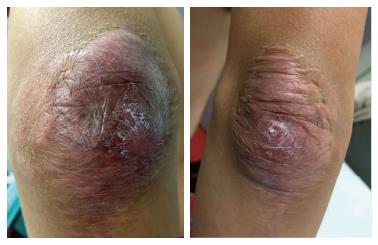

The lesions appeared at about 2 years of age on both lateral malleolus, at 3 years of age over the buttocks; they were originally asymptomatic then progressively increased in size and extent. At present time the size of the lesions varied between 1 cm × 1 cm × 1 cm to 10 cm × 5 cm (over the Achilles tendon, Figure 4) and 10 cm × 10 cm (over the buttocks, Figure 5D). On detailed clinical history the patient had symptoms of discomfort and pain in the elbows for bilateral massive tuberous xanthomas and at the age of 8, for significantly restricted joint mobility at these sites he had surgery in China in a rural hospital. Up to day the removed lesions did not recur (Figure 6). However, the discomfort and pain due to the large size of the masses of the buttocks and the limitation of his walking distance for the Achilles tendinous xanthomas progressively worsened resulting in significant disability.

Clinical examination did not reveal xanthomatous infiltration of cornea, oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal mucosae. The patient’s family history was remarkable in that both nonconsanguineous parents had a chronic hepatitis B and high total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels. The 17 years old sister had a mild hypercholesterolemia, but no other family members have shown any other inherited disorders and such similar xanthomas. The patient’s plasma TC level in the last six months ranged between 657 mg/dL and 990 mg/dL (reference value < 200), and LDL-C level was 557 mg/dL (reference value < 130). Triglycerides and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels were normal. Although not useful for the diagnosis or for clinical purposes, we also measured the plasma levels of other lipoproteins in order to better quantify the lipid profile of the patient. In particular plasma levels of apolipoprotein (Apo) A1 was normal, while the level of ApoB 345 mg/dL (reference value 55-140) and atherogenic lipoprotein (aLp) 734 mg/dL (reference value < 300) were increased.

Blood pressure was 16/11 kPa. Renal function tests, hemogram, thyroid function tests, immunoglobulins, erythrocyte sedimentation rate were all normal. The patient was suffering of a chronic hepatitis B with no current liver damage. He received a first course of entecavir therapy 0.5 mg once a day for the last 10 mo because he was tested positive for the hepatitis B “s” antigen (HBsAg), fluctuating or minimally elevated liver enzymes [alanine transaminase (ALT) 118 IU/L (reference value < 50) and aspartate transaminase (AST) 62 IU/L (reference value < 50) and very high viral load (real time HBV DNA 158000000 IU/mL)]. The patient was referred to our STDs Centre in order to establish if the dermatologic disorder was HBV-related. New test results for liver enzymes, HBV DNA, and sonography of the liver were negative.

Abdomino-pelvic ultrasonography, chest X-ray, brain magnetic resonance imaging and upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed no abnormality. No osseous pathology was noted on plain radiographs.

The patient was referred to the Metabolic Disease Centre of the University of Florence, Centre for dyslipidemia management. Echocardiography was normal. However, a transoesophageal echocardiogram revealed mild supravalvular aortic narrowing and a luminal irregularity of arch. The artery doppler ultrasound scan showed that the right carotid artery had the intima media 1.5 cm thick, and the right common femoral artery had formed atherosclerotic noncalcified plaques lesions and the intima media was 2.2 cm thick.

Based on the following findings including clinical picture, patient’s clinical history, clinical conditions still present in his family, and pathological and serological analysis the patient was diagnosed with HoFH and multiple xanthomas.

At this time the patient is treated with a combined treatment regimen of atorvastatin (20 mg/d), ezetimibe (10 mg/d), a low dose aspirin (100 mg/d) and LDL-C apheresis therapy every two weeks while on the list for anti-PCSK9 monoclonal antibody therapy.

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), is a primary hyperlipoproteinemia characterized by an autosomal codominant genetic disorder due to mutations in the LDL receptor gene located on chromosome 19. There are two types of FH: A Homozygous FH (HoFH), in that the individuals with two mutant LDL receptor alleles are much more affected than those with one mutant allele, Heterozygous FH (HeFH)[2,6,12]. HoFH is a rare form of inherited dyslipidemia often diagnosed early in childhood which in most cases is not detected. Originally, the prevalence of HoFH was estimated as 1 per million, with higher prevalence in countries with founder mutations, especially if consanguineous marriages were present. However, the HoFH prevalence is now estimated at one in 160000 to 300000[2,13]. The heteroxygous form is the most common with an incidence of 1 out 500, in which the patient has usually diagnosed as adult[12,13]. Despite published data, there is not agreement about how and when perform the screening in childhood but familial history of hypercholesterolemia in parents is crucial for detection and diagnosis of HoFH[2,11,14-16]. FH is a disease characterized by a triad: Elevated LDL-C, tendon xanthomas, and premature coronary heart disease[6]. HoFH should be suspected if both parents have HeFH where the probability of a child having HoFH is 1 in 4[16]. In HoFH patients, markedly elevated LDL-C concentration may be present at birth, as well as cutaneous xanthomas but generally present by the age of four. Corneal arcus is common by age ten and tendon xanthomas develop inevitably while coronary artery disease (CAD) develops from childhood on with high risk for a fatal or non-fatal coronary event by age thirty[5,13,15]. However, the presence of xanthomas increases the risk of CAD in patients with FH by as much as three fold. For a patient with cutaneous or tendon xanthomas, the probability of FH is very high; however, an absence of xanthoma does not rule out FH[6,15]. Epidemiologic data on cutaneous xanthomas are limited. Xanthomas are rarely seen before age twenty although those associated with FH are an exception. They tend to occur in both males and females without any sex predilection, develop inevitably and an exaggerated phenotype may be observed in patients with HoFH as was in our case[1,4,9,17,18]. The patient in the present study presented with multiple large xanthomas with a wide ranging distribution all over the body, and an onset at the age of two. The patient had an LDL-C level of 557 mg/dL, suggesting a high likelihood of HoFH. The patient was the offspring of two parents with HeFH, and appeared to have an inherited HoFH phenotype associated with an increased level of TC and serum LDL-C and more severe symptoms than the parents. The parents had mildly elevated levels of TC (father 330 mg/mL; mother 300 mg/mL), which, when combined with the absence of xanthomas, suggests that the parents suffered from HeFH. Only a minority of patients with lipoprotein disorders have xanthomas thus the estimation of plasma lipid levels alone may not be enough to properly identify a specific lipid metabolic disorder, on the contrary the presence of xanthoma lesions represent a useful marker for these diseases[4]. Therefore it seems logical that skin lesions have been described as the first symptom. Cutaneous xanthomas were first introduced in the medical field by Rayer[19] in 1835, when he described “yellow lesions on the eyelids”[19,20]. In 1851, Addison and Gull observed various forms of xanthomas naming those “vitiligoidea”[20,21]. This term was soon replaced by xanthoma by W. Frank Smith in 1869 and descriptive terms were added, such as “planum”, “multiplex” and “tuberosum”[10,12,22]. The unique association of FH and tendon xanthomas was reported by Fagge in 1873[6,23]. Xanthomas are seen in 40%-50% patients of FH and HeFH is the most common cause. Of the affected individuals 50% to 75% may complain of tendon xanthomas that rarely have been reported in the setting of normal plasma levels of cholesterol. The prevalence increases from 7% in the third decennium to 50% in the sixth decennium[1,4,10,15]. They are not palpable in up to 20% of individuals. Thus, to identify these xanthomas sonography is the most appropriate technique and is superior to clinical assessment, and even if not present an abnormal texture and thickening of Achilles tendon were demonstrated in 68% of subjects with FH[1,24,25]. Xanthelasma are seen in 23% of cases but they are the least specific of all xanthomas representing the vast majority of cases (> 95%) and because they are seen in many hyperlipidaemic and normolipidaemic states. About 65% of adult patients with xanthelasma may show normal plasma lipid levels. Tuberous xanthomas are reported in 10%-15% of cases and intertriginous xanthomas occurring occasionally[1,10]. The presence of tuberous and intertriginous xanthomas in a child with a markedly elevated plasma cholesterol level is strongly suggestive of HoFH. Intertriginous xanthomas have not been seen in the HeFH, in which plasma LDL-C are less markedly increased. In contrast, tuberoeruptive xanthomas are associated with several forms of hyperlipoproteinemia and rarely occur in patients with FH[1,4,9,10,12,16]. From detailed literature review and according to European Atherosclerosis Association Guidelines[6,13,16,26] our patient has met clinical criteria for a definite diagnosis of HoFH, even in the absence of a mutation on genetic testing, and was based on the following data: (1) High serum TC and LDL-C levels with normal triglyceride levels; (2) Appearance of xanthomas in the first decade of life; (3) Documentation of mildly elevated levels of LDL-C and TC and absence of xanthomas in both parents and in one of the siblings; (4) The presence of signs of atherosclerosis; and (5) The presence of multiple large xanthomas with a wide ranging distribution and above all, the rare pathognomonic intertriginous xanthomas, which have been described as a dermatological marker of this homozygous type.

In conclusion, this case highlights the importance of proper identification of nodular lesions and a differential diagnosis of specific subtypes of xanthomas by physicians and especially dermatologists. Xanthomas cannot be considered as simple cosmetic lesions as they are the earliest clinical indicators of lipidemic disorders. The publication of individual cases seems beneficial since this case study of HoFH wants to emphasise that this disorder remains critically under-diagnosed, and a delayed diagnosis could have potentially devastating consequences because these patients progress rapidly to atherosclerotic changes leading to aortic stenosis and CAD. Nonetheless a very important problem in these patients is that most of them do not feel ill enough until a severe CAD takes place.

Cutaneous xanthomas may or may not be present with lipid metabolic disorders, usually depending on the severity of the lipid abnormality.

Polymorphous cutaneous xanthomas in Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (HoFH).

The presence of specific lesions represents a useful marker to properly identify a specific hyperlipidaemic disorder.

High serum total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels with normal triglyceride levels.

Presence in the dermis of cholesterol crystalline aggregates surrounded by fibrosis and foamy cells.

HoFH is a rare form of inherited dyslipidemia now estimated with a prevalence of one in 160000 to 300000.

Atorvastatin, ezetimibe, low dose aspirin and LDL-C apheresis.

The presence, the clinical and dermatological features of multiple large xanthomas with a wide ranging distribution and above all, the rare pathognomonic intertriginous xanthomas, have been described as a dermatological marker of the HoFH.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Dermatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kaliyadan F, Palmirotta R, Vasconcellos C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Palacio CH, Harring TR, Nguyen NT, Goss JA, O’Mahony CA. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: case series and review of the literature. Case Rep Transplant. 2011;2011:154908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fredrickson DS, Levy RI, Lees RS. Fat transport in lipoproteins--an integrated approach to mechanisms and disorders. N Engl J Med. 1967;276:34-42 contd. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 756] [Cited by in RCA: 631] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cruz PD Jr, East C, Bergstresser PR. Dermal, subcutaneous, and tendon xanthomas: diagnostic markers for specific lipoprotein disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:95-111. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Yuan G, Wang J, Hegele RA. Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: an underrecognized cause of early cardiovascular disease. CMAJ. 2006;174:1124-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mabuchi H. Half a Century Tales of Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH) in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24:189-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jeziorska M, Hassan A, Mackness MI, Woolley DE, Tullo AB, Lucas GS, Durrington PN. Clinical, biochemical, and immunohistochemical features of necrobiotic xanthogranulomatosis. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:64-68. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Szalat R, Arnulf B, Karlin L, Rybojad M, Asli B, Malphettes M, Galicier L, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Harel S, Cordoliani F. Pathogenesis and treatment of xanthomatosis associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Blood. 2011;118:3777-3784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vargas-Flores E, Estrada-Alpizar L, Arenas-Osuna J. Tuberous Xanthomatosis as a Presentation of Familial Hypercholesterolemia. JSM Clin Case Rep. 2016;4:1114. |

| 10. | Kumar N, Anand S, Yadav C, Kataria H, Kumar P, Yadav S. Xanthomatosis and Orthopaedics: Review of literature. Int Res J Basic Clin Stud. 2014;2:78-81. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Fernandes M, Pereira P. A case of type IIa Homozygous Familial Hypercholestrolemia with cutaneous xanthomas. IJMRHS. 2015;1:1-3. |

| 12. | Jayaram S, Meera S, Kadi S, Sreenivasa N. An Interesting Case of Familial Homozygous Hypercholesterolemia-A Brief Review. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2012;27:309-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Janus ED. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia - Early recognition and early treatment improve outcomes. Atherosclerosis. 2017;260:147-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bermudez EB, Storey L, Mayo S, Simpson G. An Unusual Case of Multiple Tendinous Xanthomas Involving the Extremities and the Ears. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:340-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhao C, Kong M, Cao L, Zhang Q, Fang Y, Ruan W, Dou X, Gu X, Bi Q. Multiple large xanthomas: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:4327-4332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | France M. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: update on management. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2016;36:243-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Huijgen R, Stork AD, Defesche JC, Peter J, Alonso R, Cuevas A, Kastelein JJ, Duran M, Stroes ES. Extreme xanthomatosis in patients with both familial hypercholesterolemia and cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Clin Genet. 2012;81:24-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wani IH, Farooq M, Bhat MS, Lone A, Kamal Y, Latoo I. Lumpy bumpy Achilles with gait instability could be cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: Two case reports. FAOJ. 2014;7:3. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Rayer P. Plaques jaunes folliculeuses, developpées sur la paupière supérieure. Atlas du Traité des maladies de la peau, 1835: Pl VIII, figure 16, and Pl XXII, figure 15. |

| 20. | Fleischmajer R, Schragger AH. The clinical significance of cutaneous xanthomas. Postgrad Med J. 1970;46:671-677. [PubMed] |

| 21. |

Addison T, Gull W.

On a Certain Affection of the Skin: Vitiligoidea-Plana-Tuberosa, with Remarks and Plates. |

| 22. |

Smith FW.

On xanthoma or vitiligoidea. |

| 23. |

Fagge CH.

Xanthomatous disease of the skin. General xanthelasma or viltiligoides. |

| 24. | Junyent M, Gilabert R, Zambón D, Núñez I, Vela M, Civeira F, Pocoví M, Ros E. The use of Achilles tendon sonography to distinguish familial hypercholesterolemia from other genetic dyslipidemias. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2203-2208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dagistan E, Canan A, Kizildag B, Barut AY. Multiple tendon xanthomas in patient with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: sonographic and MRI findings. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:pii: bcr2013200755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cuchel M, Bruckert E, Ginsberg HN, Raal FJ, Santos RD, Hegele RA, Kuivenhoven JA, Nordestgaard BG, Descamps OS, Steinhagen-Thiessen E. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: new insights and guidance for clinicians to improve detection and clinical management. A position paper from the Consensus Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolaemia of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2146-2157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 760] [Cited by in RCA: 758] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |