Published online Mar 18, 2017. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.278

Peer-review started: October 19, 2016

First decision: November 14, 2016

Revised: November 27, 2016

Accepted: December 13, 2016

Article in press: December 14, 2016

Published online: March 18, 2017

Processing time: 154 Days and 20.8 Hours

To investigate the correlations between clinical outcomes and biopsychological variables in female patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA).

Seventy-seven patients with symptomatic knee OA were enrolled in this study. We investigated the age, body mass index (BMI), pain catastrophizing scale (PCS) and radiographic severity of bilateral knees using a Kellgren-Lawrence (K-L) grading system of the subjects. Subsequently, a multiple linear regression was conducted to determine which variables best correlated with main outcomes of knee OA, which were pain severity, moving capacity by measuring timed-up-and-go test and Japanese Knee Osteoarthritis Measure (JKOM).

We found that the significant contributor to pain severity was PCS (β = 0.555) and BMI (β = 0.239), to moving capacity was K-L grade (β = 0.520) and to PCS (β = 0.313), and to a JKOM score was PCS (β = 0.485) and K-L grade (β = 0.421), respectively.

The results suggest that pain catastrophizing as well as biological factors were associated with clinical outcomes in female patients with knee OA, irrespective of radiographic severity.

Core tip: Plenty of previous studies have focused on biological factors such as aging, gender, body mass index, ethnicity and history of knee injury for knee pain in cases where there was a discordant relationship between radiographic severity and symptoms in knee osteoarthritis (OA). However, in the present study, we found that pain catastrophizing thought was highly associated with knee-related clinical outcomes, irrespective of radiographic severity, for female patients with knee OA, especially pain severity and quality of life.

- Citation: Ikemoto T, Miyagawa H, Shiro Y, Arai YCP, Akao M, Murotani K, Ushida T, Deie M. Relationship between biological factors and catastrophizing and clinical outcomes for female patients with knee osteoarthritis. World J Orthop 2017; 8(3): 278-285

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v8/i3/278.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v8.i3.278

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a common problem causing knee pain and functional decline and disabilities in the elderly[1-3]. Although there is a widespread belief of inconsistency between clinical symptoms and radiographic disease severity[4], recent studies have revealed that knee symptoms were associated with not only disease severity but also female gender, aging, overweight and psychological factors[5-11], in spite of the fact that these independent variables are sometimes associated with each other.

To establish comprehensive outcome measures relevant to the disabilities, the OMERACT conference first convened in 1992 (OMERACT was originally an acronym for Outcome Measures in RA Clinical Trials, now it represents the more inclusive scope of “Outcome Measures in Rheumatology”). Several years later, a key objective of the OMERACT III conference was to establish a core set of outcome measures for OA[12]. A consensus was reached by at least 90% of expert participants that the following 4 domains should be evaluated for knee, hip, and hand OA: Pain, physical function, patient global assessment, and joint imaging.

On the other hand, although a number of previous studies have revealed that radiographic disease severity, female gender, aging, being overweight and psychological factors such as catastrophizing thought were related to knee OA symptoms, it still remains unclear which variables best correlated with clinical disability.

It has been established that women are more sensitive to pain than men[13], and more likely to complain of chronic musculoskeletal burden compared to men[14]. Moreover, it has been suggested that women reported greater levels of catastrophizing with more painful symptoms than men[15]. Recently, pain catastrophizing has been studied in patients suffering from knee OA[11,16], and Somers et al[16] have reported that pain catastrophizing rather than radiographic severity appears to be an important variable in understanding pain, disability, and physical function in overweight/obese patients with knee OA. Therefore, it would be important to understand the lack of relationships between the outcomes of knee OA and related variables for female patients with knee OA. Hence, the aim of the present study was to address the correlations between each of the clinical outcomes or between each outcome and relevant variables in knee OA patients with chronic pain or stiffness, limited to female participants using bivariate correlation and multivariate regression analysis. We speculated that pain catastrophizing rather than radiographic severity was a more influential factor for predicting the severity of knee pain, functional capacity, and quality of life for female patients with knee OA.

A previous study found relationships (pr2 = 0.10) between pain catastrophizing and pain severity of knee OA patients[16]. Based on this finding, the sample size for a power of 0.80 with two-tailed alpha at a 0.05 significance level to run a multivariate regression for seven predictors required a minimum of 74 subjects. After obtaining approval from the ethics committee, we announced research related to knee symptoms in female elderly patients 50 years of age or older from February to August 2015 and recruited participants who were interested in this study through physical-fitness center or orthopedic clinic located within Aichi Medical University. Before investigating their status, each subject was fully informed by the investigator 1: that content of this study and 2: that the personal information of the subject would be kept confidential.

Ninety-five people with chronic knee symptoms were interested in the study and they received a knee X-ray to confirm if they were eligible for the study. The eligibility criteria for this study were as follows: (1) female with knee symptoms persisting for at least three months or more; (2) 50 years old or older; (3) radiographic knee OA with a face of more than grade-2 according to the Kellgren-Lawrence (K-L) grading system on at least a unilateral knee, because most previous studies used grade-2 as a main defining feature for radiographic knee OA; and excluded (4) presence or history of major neurological disorders such as stroke and Parkinson’s disease, and history of total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

In the end, we enrolled 77 female patients with knee pain in this study.

Demographical background: First, we investigated the age, and body mass index (BMI) of the subjects. The BMI was calculated from weight and height measurements using the formula BMI = weight (in kg) divided by height (in m-2).

After investigation of the subjects’ demographic background (age, BMI), they underwent a radiographic examination of both knees by posterior-anterior view in the fixed standing position by a radiological technician. To avoid assessment error, all radiographs were assessed by two orthopedic physicians together (Tatsunori Ikemoto and Machiko Akao) according to the K-L grading system that uses the following grades: 0, normal; 1, possible osteophytes only; 2, definite osteophytes and possible joint space narrowing; 3, moderate osteophytes and/or definite joint space narrowing; and 4, large osteophytes, severe joint space narrowing, and/or bony sclerosis[17].

Previous studies related to knee OA have assessed either side, although OA often affects bilateral knees[18] and this bilaterality may amplify the magnitude of symptoms[19]. Firstly, we assigned the subjects into either a unilateral group or a bilateral group according to whether radiographic knee OA was observed in one side or both sides. Subsequently, we used the total score of both sides (e.g., if the right side was grade-2 and the left side was grade-1 then the total was 3) as radiographic severity because of the possibility that they have a substantial influence on the outcome measures despite asymptomatic knees[20].

The Japanese Knee Osteoarthritis Measure (JKOM) was developed to reflect the specifics of the Japanese cultural lifestyle, which is characterized by bending to the floor or standing up[21]. The validity and reliability of JKOM has been examined by comparing it with the widely accepted QOL measure, the Western Ontario and McMaster University osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) and the 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). The JKOM consists of a pain rating based on a visual analogue scale (VAS) which was a 100-mm line with “no pain” at one end and “worst pain possible” at the other end and scores for a subscale of four symptoms based on a disease-specific questionnaire addressing four dimensions: “Pain and stiffness in knee”, “condition in daily life”, “general activities” and “health conditions”, with 8, 10, 5 and 2 items, respectively. Each item is rated on an ordinal scale from 0-4, with higher scores indicating a symptom or medical condition of higher severity. The four symptom subscales can be scored separately or combined to represent the aggregated total symptoms. Lower JKOM scores indicate better QOL. We assessed the pain severity of participants in accordance with the VAS score.

Catastrophizing was assessed using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS). The PCS consists of 13 items that describe an individual’s specific beliefs about their pain and evaluates catastrophic thinking about pain[22].

Participants responded to each item using a Likert-type scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“all the time”). The scale provides a total score and scores on 3 subscales: Rumination (4 items), magnification (3 items), and helplessness (6 items)[23]. This scale is well known for its reliability and validity in the Japanese version[24]. Although catastrophizing is known to be a cognitive distortion closely linked to anxiety and depression[22], we confirmed that no subjects took anti-anxiety drugs or anti-depressants in the present study.

Timed up and go test (TUG) measures the time it takes a subject to stand up from a chair (46 cm seat height from the ground), walk a distance of 3 m, turn and walk back to the chair, and sit down[25]. All subjects performed two trials and the superior time was used. TUG was originally established as an objective measure of physical function in the elderly population. It is also used to assess the risk of falls in older adults[26].

Data were presented as mean and standard deviation and median because each variable resulted in not only parametric but also non-parametric distributions.

We assumed that there were three outcomes, which were pain rating, TUG, and the JKOM score as essential measures for knee OA based on the OMERACT III description. Firstly, we compared the differences in the scores of each outcome between the unilateral group and bilateral group by using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Subsequently, we also determined the four independent variables: Age, BMI, K-L grade, and PCS score, which were assumed to influence each clinical outcome. The relationship between each of the variables was analyzed using Spearman’s correlation for bivariate regression analysis. Further analysis using a stepwise multiple linear regression was conducted to determine which independent variables best correlated with the severity of each outcome measure.

For a priori power analysis, we used G*power3 software[27] to determine sample size for study destination. Bivariate correlation analysis and multivariate regression analysis were performed with SPSS software (version 20.0J; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Differences were always considered significant at a level of P < 0.05.

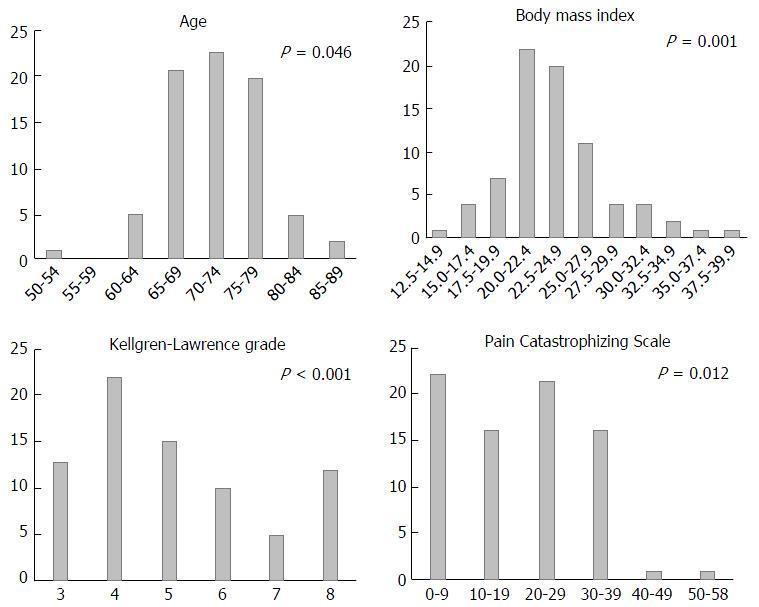

The subject characteristics are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1 shows the distributions of the scores of each independent variable.

| Variables | n = 77 |

| Age (yr) | 72 (50-86) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.7 (14.5-41.7) |

| K-L grade (Rt + Lt) | 5 (3-8) |

| PCS | 20 (0-50) |

| Pain rating (VAS) | 26 (0-99) |

| TUG (s) | 6.0 (4.1-16.5) |

| JKOM | 18 (1-81) |

The subjects were assigned as follow: 17 subjects (22%) in the unilateral group; and 60 subjects (78%) in the bilateral group. Comparisons of the dichotomous groups revealed that there were no significant differences in severity of knee pain and JKOM scores between the unilateral group and bilateral group, while TUG was significantly faster in the unilateral group than in the bilateral group (Table 2).

| Variables | Unilateral (n = 17) | Bilateral (n = 60) | P-value |

| Pain rating (VAS) | 24 (0-95) | 26 (0-99) | 0.51 |

| TUG (s) | 5.5 (4.4-7.2) | 6.3 (4.1-16.5) | 0.02 |

| JKOM | 13 (2-35) | 18 (1-81) | 0.23 |

The correlation coefficients (ρ) between each of the clinical outcomes or between each outcome and relevant variables using a bivariate regression analysis are shown in Table 3. Each outcome measure was significantly associated with each other. The pain rating showed significant positive correlations with K-L grade and PCS. TUG showed significant positive correlations with BMI, K-L grade, and PCS. The JKOM score showed a significant positive correlation with K-L grade and PCS.

In addition, the results of a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis for each outcome measure are shown in Table 4. We found that the significant contributor to a pain rating was PCS (β = 0.555) and BMI (β = 0.239), to TUG was K-L grade (β = 0.520) and PCS (β = 0.313), and to a JKOM score was PCS (β = 0.485) and K-L grade (β = 0.421), respectively.

| Outcome | Independent variables | R2 | Unstandardized coefficients: B | 95%CI for B | β | P-value |

| Pain rating | 0.397 | |||||

| BMI | 0.162 | 0.039-0.284 | 0.239 | 0.010 | ||

| PCS | 0.139 | 0.093-0.184 | 0.555 | < 0.001 | ||

| TUG | 0.431 | |||||

| K-L grade | 0.638 | 0.419-0.856 | 0.52 | < 0.001 | ||

| PCS | 0.053 | 0.023-0.082 | 0.313 | 0.001 | ||

| JKOM | 0.492 | |||||

| K-L grade | 4.556 | 2.737-6.374 | 0.421 | < 0.001 | ||

| PCS | 0.719 | 0.470-0.968 | 0.485 | < 0.001 |

In the present study, although there is some disagreement regarding our speculation, pain catastrophizing has been highly associated with knee-related clinical outcomes for female patients with knee OA, especially pain severity and QOL score. To our knowledge, this is the first report that comprehensively investigates the relationships between knee OA related outcomes and related factors limited to female samples.

Knee pain with OA is known as a cause of disabilities among older adults as well as low back pain[28,29]. Knee pain is also an important outcome for patients with knee OA. However, previous studies have focused on biological factors such as aging, gender, BMI, ethnicity and history of knee injury for knee pain in cases where there was a discordant relationship between radiographic severity and symptoms[4,30]. On the other hand, recent studies have suggested that there were apparent relationships between pain catastrophizing and physical disabilities as well as pain severity in both pediatric and adult patients with musculoskeletal disorders[11,31,32]. Moreover, Forsythe et al[33] have reported that preoperative PCS scores predicted the presence of postoperative pain in patients who received TKA for primary knee OA.

In the present study, we found no interrelationships between pain catastrophizing and age, BMI and radiographic severity, while pain catastrophizing was a significant predictor which correlated with pain severity, and disease-specific QOL scores in female patients with knee OA, irrespective of disease severity. This finding is not only consistent with a previous report[16], but also suggests that pain catastrophizing is an important factor rather than aging, and body weight associated with physical disabilities in female patients with knee OA, if radiographic severity is progressive.

The term catastrophizing was originally introduced by Ellis[34] and subsequently adapted by Beck et al[35] to describe a mal-adaptive cognitive style employed by patients with anxiety and depressive disorders. Keefe et al[36] found a high test-retest correlation between catastrophizing thought during a 6-mo period in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and suggested it was invariable. Three prospective studies of TKA have included measures of catastrophizing in their test batteries[31,37,38]. In these studies, catastrophizing scores did not significantly decline over time despite reduced pain in study participants and therefore it could be a personality trait such as neuroticism. By contrast, Wada et al[39] recently reported that a change in pain intensity was associated with a change in catastrophizing for patients with TKA during a 6-mo follow-up. Furthermore, a number of studies have examined whether pain catastrophizing is an active cognitive process variable in multidisciplinary pain treatment settings, and have shown that pre- to post-treatment reductions in pain catastrophizing are associated with reductions in pain severity[40-42]. Indeed, Marra et al[43] have reported that multidisciplinary intervention for knee OA was superior to usual care with an educational pamphlet in terms of overall improvements, pain and function scores according to the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities’ Osteoarthritis Index.

Besides, in the present study, TUG as an index of moving capacity was associated with not only disease severity but also pain catastrophizing after adjusting for BMI. We found that a correlation coefficient between TUG and K-L grade was higher than that between TUG and pain rating. This indicates that an assessment of bilateral knees may predict the moving capacity in female patients with knee OA, irrespective of pain severity. While a significant relationship between moving capacity and catastrophizing was consistent with a report by Somers et al[16], the underlying mechanism, which can explain the correlation between them, is still unknown. Perhaps, pain-related fear may be related to physical performance with effort (i.e., walking fast) in chronic pain[16,44].

Taken together, this study suggests that clinicians should make sure to include an assessment of radiographic severity bilaterally and pain catastrophizing to explain the outcome measures in female patients with knee OA. This is because they may be able to improve both functional capacity and symptoms even at a progressive stage without knee arthroplasty by psychological intervention, which ameliorates mal-adaptive cognition in patients with high catastrophizing thought.

Several limitations should be taken into account when interpreting our data. Firstly, this was a cross-sectional study, therefore causal relationships between each outcome score and related variables could not be identified. Further longitudinal investigation is necessary to identify the interactions between the chronology of outcome measures and changes in variables. Secondly, the severity of radiographic OA was only assessed by posterior-anterior view in this study, although knee joints consisted of three components. Lanyon et al[45] have reported that 24% of patients with radiographic knee OA was missed by not visualizing the patella-femoral joint. Thirdly, although we assess biological and psychological factors as influential variables on the outcome in knee OA, we didn’t evaluate the strength of the quadriceps, which has been consistently associated with knee pain and disabilities[46]. Furthermore, we didn’t evaluate the patient’s background such as underlying disease, educational level and previous treatment which might be associated with clinical outcome. Finally, we have emphasized catastrophizing for the outcome and mentioned the possibility of improving catastrophizing thought in patients with chronic pain by a multifaceted intervention. However, there is little consensus on the effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for knee OA pain[47]. Hence, we must attempt to ameliorate these limitations and conduct a further investigation into whether an intervention to catastrophizing in relation to knee pain can improve the clinical outcomes for the female patient with knee OA.

This study showed that pain catastrophizing was a significant predictor which correlated with pain severity, physical function, and disease-specific QOL scores in female patients with knee OA, irrespective of disease severity. This finding suggests that pain catastrophizing is an important factor to explain knee symptoms and disabilities in female patients with knee OA.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Matthew McLaughlin for his assistance in editing the manuscript.

There is a widespread belief of inconsistency between clinical symptoms and radiographic disease severity in knee osteoarthritis (OA). Recent studies revealed that knee symptoms were associated with not only disease severity but also female gender, aging, overweight and psychological factors. However, there is little evidence reporting comprehensive relationships between biological and psychological factors and severity of symptoms in female patients with knee OA.

Although a recent study has suggested that pain catastrophizing thought, as a psychological factor for pain symptoms, was associated with functional capacity as well as severity of knee pain in patients with knee OA, to what extent this psychological factor contributes to the severity of symptoms in female patients with knee OA, is still poorly understood. The research hotspot is to introduce the contributing degrees of both biological and psychological factors to the severity of symptoms in female patients with knee OA.

Knee pain is an important outcome for patients with knee OA. However, previous studies have focused on biological factors such as aging, gender, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity and history of knee injury for knee pain in cases where there was a discordant relationship between radiographic severity and symptoms. On the other hand, the study revealed that pain catastrophizing has been highly associated with knee-related clinical outcomes for female patients with knee OA, irrespective of disease severity, especially pain severity and QOL score. To our knowledge, this is the first report that comprehensively investigates the relationships between knee OA related outcomes and related factors limited to female samples.

This study suggests that clinicians should make sure to include an assessment of pain catastrophizing as well as radiographic severity to explain the outcome measures in female patients with knee OA, because they may be able to improve both functional capacity and symptoms even in a progressive stage without knee arthroplasty by psychological interventions which ameliorate mal-adaptive cognition in patients with high catastrophizing thought.

The term “catastrophizing” was originally introduced by Albert Ellis and subsequently adapted by Aaron Beck to describe a mal-adaptive cognitive style employed by patients with anxiety and depressive disorders. In the present study, catastrophizing was assessed using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) invented by Sullivan et al (1995). The PCS consists of 13 items that describe an individual’s specific beliefs about their pain and evaluates catastrophic thinking about pain.

The authors investigated the factors associated with clinical outcomes in female patients with knee OA. They concluded that pain catastrophizing scores well correlated with ADL scores and gait ability. The manuscript was concise and well written.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cui Q, Ohishi T, Tangtrakulwanich B, Vaishya R S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T, Brammah T, Busby H, Roxby M, Simmons A, Williams G. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 796] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sharma L, Kapoor D, Issa S. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18:147-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Muraki S, Oka H, Akune T, Mabuchi A, En-yo Y, Yoshida M, Saika A, Suzuki T, Yoshida H, Ishibashi H. Prevalence of radiographic knee osteoarthritis and its association with knee pain in the elderly of Japanese population-based cohorts: the ROAD study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:1137-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Bedson J, Croft PR. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 624] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Neogi T, Felson D, Niu J, Nevitt M, Lewis CE, Aliabadi P, Sack B, Torner J, Bradley L, Zhang Y. Association between radiographic features of knee osteoarthritis and pain: results from two cohort studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b2844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Andersen RE, Crespo CJ, Ling SM, Bathon JM, Bartlett SJ. Prevalence of significant knee pain among older Americans: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1435-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nguyen US, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Niu J, Zhang B, Felson DT. Increasing prevalence of knee pain and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: survey and cohort data. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:725-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Felson DT, Zhang Y, Anthony JM, Naimark A, Anderson JJ. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in women. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:535-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 621] [Cited by in RCA: 542] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jiang L, Tian W, Wang Y, Rong J, Bao C, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Wang C. Body mass index and susceptibility to knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:291-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Peltonen M, Lindroos AK, Torgerson JS. Musculoskeletal pain in the obese: a comparison with a general population and long-term changes after conventional and surgical obesity treatment. Pain. 2003;104:549-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Egert JR, Affleck G, Sullivan MJ, Caldwell DS. The relationship of gender to pain, pain behavior, and disability in osteoarthritis patients: the role of catastrophizing. Pain. 2000;87:325-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 505] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bellamy N, Kirwan J, Boers M, Brooks P, Strand V, Tugwell P, Altman R, Brandt K, Dougados M, Lequesne M. Recommendations for a core set of outcome measures for future phase III clinical trials in knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis. Consensus development at OMERACT III. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:799-802. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Racine M, Tousignant-Laflamme Y, Kloda LA, Dion D, Dupuis G, Choinière M. A systematic literature review of 10 years of research on sex/gender and pain perception - part 2: do biopsychosocial factors alter pain sensitivity differently in women and men? Pain. 2012;153:619-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Andorsen OF, Ahmed LA, Emaus N, Klouman E. High prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal complaints among women in a Norwegian general population: the Tromsø study. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Sullivan MJ, Fillingim RB. Catastrophizing as a mediator of sex differences in pain: differential effects for daily pain versus laboratory-induced pain. Pain. 2004;111:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, Pells JJ, Dixon KE, Waters SJ, Riordan PA, Blumenthal JA, McKee DC, LaCaille L, Tucker JM. Pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in osteoarthritis patients: relationships to pain and disability. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:863-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9311] [Cited by in RCA: 8886] [Article Influence: 130.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Naimark A, Weissman BN, Aliabadi P, Levy D. The incidence and natural history of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1500-1505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 477] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | White DK, Zhang Y, Felson DT, Niu J, Keysor JJ, Nevitt MC, Lewis CE, Torner JC, Neogi T. The independent effect of pain in one versus two knees on the presence of low physical function in a multicenter knee osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:938-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Taniguchi N, Matsuda S, Kawaguchi T, Tabara Y, Ikezoe T, Tsuboyama T, Ichihashi N, Nakayama T, Matsuda F, Ito H. The KSS 2011 reflects symptoms, physical activities, and radiographic grades in a Japanese population. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:70-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Akai M, Doi T, Fujino K, Iwaya T, Kurosawa H, Nasu T. An outcome measure for Japanese people with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1524-1532. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Sullivan MJL, Bishop S, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:432-524. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4428] [Cited by in RCA: 4459] [Article Influence: 148.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Van Damme S, Crombez G, Bijttebier P, Goubert L, Van Houdenhove B. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale: invariant factor structure across clinical and non-clinical populations. Pain. 2002;96:319-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Iwaki R, Arimura T, Jensen MP, Nakamura T, Yamashiro K, Makino S, Obata T, Sudo N, Kubo C, Hosoi M. Global catastrophizing vs catastrophizing subdomains: assessment and associations with patient functioning. Pain Med. 2012;13:677-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & amp; Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8741] [Cited by in RCA: 9347] [Article Influence: 274.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Beauchet O, Fantino B, Allali G, Muir SW, Montero-Odasso M, Annweiler C. Timed Up and Go test and risk of falls in older adults: a systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15:933-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13379] [Cited by in RCA: 16873] [Article Influence: 1124.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Song J, Chang RW, Dunlop DD. Population impact of arthritis on disability in older adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:248-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Stamm TA, Pieber K, Crevenna R, Dorner TE. Impairment in the activities of daily living in older adults with and without osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and chronic back pain: a secondary analysis of population-based health survey data. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Murphy LB, Moss S, Do BT, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, Barbour KE, Renner J, Kalsbeek W, Jordan JM. Annual Incidence of Knee Symptoms and Four Knee Osteoarthritis Outcomes in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:55-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sullivan MJ, Stanish W, Waite H, Sullivan M, Tripp DA. Catastrophizing, pain, and disability in patients with soft-tissue injuries. Pain. 1998;77:253-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Vervoort T, Goubert L, Eccleston C, Bijttebier P, Crombez G. Catastrophic thinking about pain is independently associated with pain severity, disability, and somatic complaints in school children and children with chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:674-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Forsythe ME, Dunbar MJ, Hennigar AW, Sullivan MJ, Gross M. Prospective relation between catastrophizing and residual pain following knee arthroplasty: two-year follow-up. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ellis A. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. NY, USA: Lyle Stuart 1962; . |

| 35. | Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. NY, USA: Guilford Press 1979; . |

| 36. | Keefe FJ, Brown GK, Wallston KA, Caldwell DS. Coping with rheumatoid arthritis pain: catastrophizing as a maladaptive strategy. Pain. 1989;37:51-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 487] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Roth ML, Tripp DA, Harrison MH, Sullivan M, Carson P. Demographic and psychosocial predictors of acute perioperative pain for total knee arthroplasty. Pain Res Manag. 2007;12:185-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT, Klick B, Katz JN. Catastrophizing and depressive symptoms as prospective predictors of outcomes following total knee replacement. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14:307-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Wade JB, Riddle DL, Thacker LR. Is pain catastrophizing a stable trait or dynamic state in patients scheduled for knee arthroplasty? Clin J Pain. 2012;28:122-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Jensen MP, McFarland CA. Increasing the reliability and validity of pain intensity measurement in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1993;55:195-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Lawler BK. Relationship of pain-specific beliefs to chronic pain adjustment. Pain. 1994;57:301-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. Changes in beliefs, catastrophizing, and coping are associated with improvement in multidisciplinary pain treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:655-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Marra CA, Cibere J, Grubisic M, Grindrod KA, Gastonguay L, Thomas JM, Embley P, Colley L, Tsuyuki RT, Khan KM. Pharmacist-initiated intervention trial in osteoarthritis: a multidisciplinary intervention for knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1837-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Geisser ME, Robinson ME, Miller QL, Bade SM. Psychosocial factors and functional capacity evaluation among persons with chronic pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13:259-276. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Lanyon P, O’Reilly S, Jones A, Doherty M. Radiographic assessment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the community: definitions and normal joint space. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:595-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Glass NA, Torner JC, Frey Law LA, Wang K, Yang T, Nevitt MC, Felson DT, Lewis CE, Segal NA. The relationship between quadriceps muscle weakness and worsening of knee pain in the MOST cohort: a 5-year longitudinal study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1154-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Helminen EE, Sinikallio SH, Valjakka AL, Väisänen-Rouvali RH, Arokoski JP. Effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioral group intervention for knee osteoarthritis pain: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |