Published online Oct 18, 2013. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v4.i4.327

Revised: June 7, 2013

Accepted: June 19, 2013

Published online: October 18, 2013

Processing time: 249 Days and 19.7 Hours

We report a case of a 32 year-old male, admitted for a lytic lesion of the distal femur. One month after the first X-ray, clinical and imaging deterioration was evident. Open biopsy revealed fibrous dysplasia. Three months later, the lytic lesion had spread to the whole distal third of the femur reaching the articular cartilage. The malignant clinical and imaging features necessitated excision of the lesion and reconstruction with a custom-made total knee arthroplasty. Intra-operatively, no obvious soft tissue infiltration was evident. Nevertheless, an excision of the distal 15.5 cm of the femur including 3.0 cm of the surrounding muscles was finally performed. The histological examination of the excised specimen revealed central low-grade osteosarcoma. Based on the morphological features of the excised tumor, allied to the clinical findings, the diagnosis of low-grade central osteosarcoma was finally made although characters of a fibrous dysplasia were apparent. Central low-grade osteosarcoma is a rare, well-differentiated sub-type of osteosarcoma, with clinical, imaging, and histological features similar to benign tumours. Thus, initial misdiagnosis is usual with the condition commonly mistaken for fibrous dysplasia. Central low-grade osteosarcoma is usually treated with surgery alone, with rare cases of distal metastases. However, regional recurrence is quite frequent after close margin excision.

Core tip: We report a case of a 32 year-old male, admitted for a lytic lesion of the distal femur. Although open biopsy suggested fibrous dysplasia, clinical and radiological evaluation indicated malignancy. Histological examination of the excised specimen revealed central low-grade osteosarcoma. Central low-grade osteosarcoma is a rare, well-differentiated, sub-type of osteosarcoma, with clinical, imaging, and histological features in keeping with benign tumours. Thus, initial misdiagnosis is common, typically being mistaken for fibrous dysplasia. Central low-grade osteosarcoma is usually treated with surgery in isolation, with rare cases of distal metastases. However, regional recurrence is quite frequent after close margin excision.

- Citation: Vasiliadis HS, Arnaoutoglou C, Plakoutsis S, Doukas M, Batistatou A, Xenakis TA. Low-grade central osteosarcoma of distal femur, resembling fibrous dysplasia. World J Orthop 2013; 4(4): 327-332

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v4/i4/327.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v4.i4.327

Low-grade central osteosarcoma (LGCO) is a rare well-differentiated sub-type of osteosarcoma[1]. It is first described by Unni et al[2] who reported 27 patients with an “Intraosseous well-differentiated osteosarcoma”. Since then, only a few cases of LGCO have been reported being variously described as “well-differentiated intramedullary osteosarcoma”, “low grade intraosseous osteosarcoma”, “central osteosarcoma of low-grade malignancy”, or ” low-grade endosteal osteosarcoma”[2-5].

LGCO usually presents in the third decade of life, with an almost equal male to female ratio[2,3,6,7]. It represents less than 2% of all osteosarcomas[8]. Metaphyseal region of the long bones is usually affected, while distal femur and proximal tibia are involved in more than half of the cases and long bones in over 80%[2,3,6]. Its high differentiation and relatively low malignancy contribute to an extremely high rate of initial misdiagnoses, typically masquerading as fibrous dysplasia.

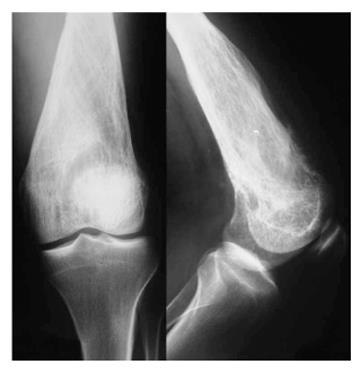

A 32 year-old male attended our institute complaining of pain and swelling of his left knee over a period of 3 to 4 mo. Clinical examination revealed a solid expansion of the distal femur with no signs of effusion or inflammation. Plain X-rays showed a lytic lesion occupying the distal third of the femur including the medial and lateral condyle, reaching the subchondral area of the knee joint (Figure 1A). Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1B and C) confirmed the lytic characters of the lesion which was found to spread mainly intramedullary, without expansion beyond the joint. Low signal was seen in T1-weight images and intermediate in STIR with areas of cortical interruption and periosteal reaction. Soft tissue infiltration was also evident focally. The patient was initially discharged and advised to avoid weight bearing with close observation.

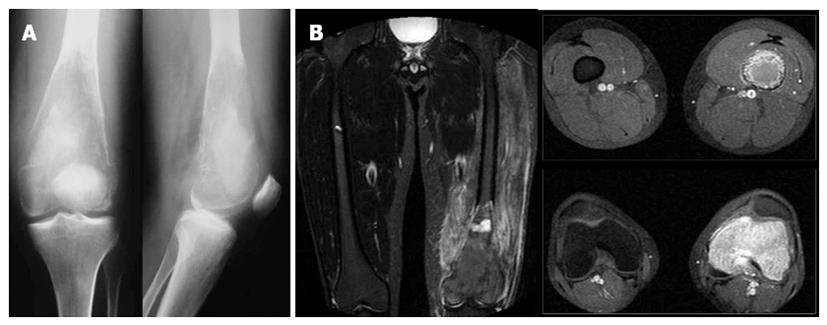

One month later, X-ray images revealed deterioration of the characteristics of the lesion, with more obvious lysis of the distal femur (Figure 2). Thick and coarse trabeculation had become apparent, while cortical perforation was found especially to the anterior cortex. Meanwhile, an methylene diphosphonate bone scan was performed, showing an increased uptake at the distal femur at the lesion area, with no further cephalic or distal expansion. No other spots of increased uptake were apparent in the rest of the skeleton. CT scan of the thoracic cavity and abdomen was also negative for metastasis.

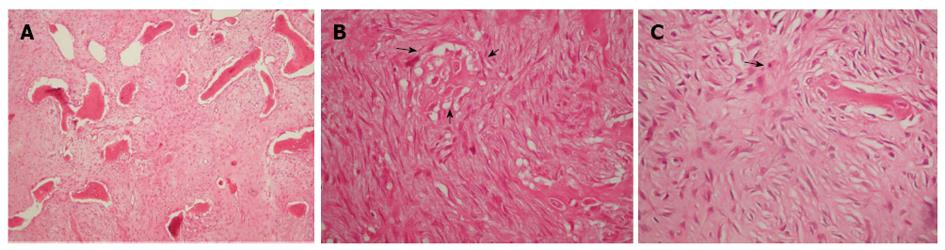

Open biopsy was performed obtaining bone specimens from the outer lateral condyle with 3 cm × 2 cm × 1 cm total dimensions. The tissue specimen consisted of multiple tan-grey fragments with a bony texture. Microscopic examination revealed a lesion consisting of fibrous and osseous components, in variable amounts in all sections. The fibrous stroma was composed of spindle-shaped cells without features of malignancy. Non-stress oriented trabeculae of immature bone without osteoblastic rimming, as well as haphazardly shaped trabeculae (“alphabet soup”) were also observed. The morphologic features were consistent with fibrous dysplasia.

However, the wide extent of the tumour and the involvement of both the femoral condyles and the subchondral area were considered to increase the risk of a pathological fracture or total joint surface depression. Moreover, the clear evidence of deterioration on the images allied to the signs of cortical perforation with focal soft tissue infiltration increased the clinical suspicion of malignancy. Therefore, despite the benign histological diagnosis, a wide excision of the upper femur (involving tumor removal with a margin of at least 3 cm of normal tissue) was undertaken followed by a hinged custom-made total knee arthroplasty (Howmedica Modular Resection System, Stryker Howmedica Osteonics, Inc).

Readmission of the patient for the arthroplasty procedure three months after the first admission, revealed a severely affected bone radiographically (Figure 3). Lysis of the distal femur with elimination of the bone trabeculation was accompanied by a compressive fracture of the metaphysis (Figures 3A, 4A). Severe pain was provoked even with partial weight bearing, while clinical examination revealed paradox mobility of the distal femur. A new MRI was performed. In contrast to the plain X-rays, the MRI showed similar findings to the previous image, with no evidence of wider extension of the lesion. However, a high signal to the STIR-weight images revealed an increased oedema of the surrounding muscles, probably due to a haematoma secondary to the fracture (Figure 3B).

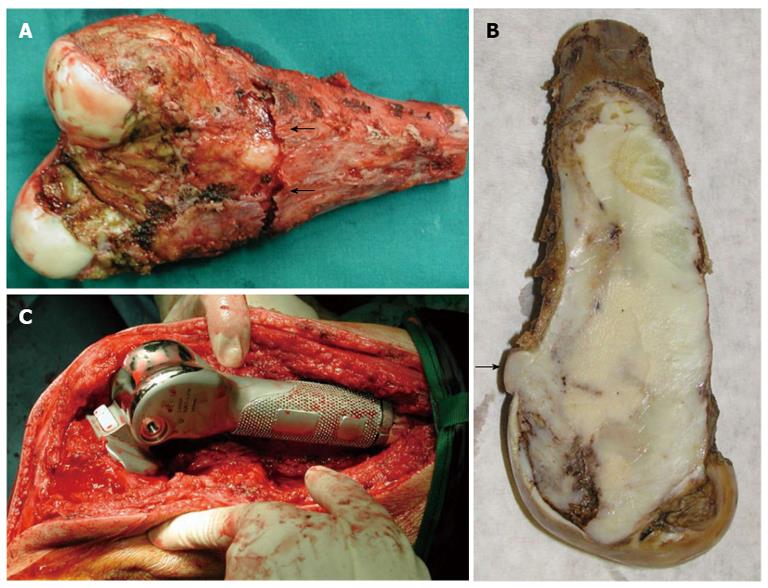

Intra-operatively, no obvious soft tissue infiltration was evident. Nevertheless, an excision of the distal 15.5 cm of the femur including 3.0 cm of the surrounding muscles was finally performed (Figure 4A and B).

Macroscopically, a large well-demarcated, grey-white mass with a firm and gritty texture, measuring 15.5 cm × 5.0 cm was excised and sent for histological evaluation. The tumor arose within the medullary cavity and extended from the cartilage surface to within 3 cm distance from the excision line (Figure 4A and B). The cartilage had a chondral lesion (Outerbridge grade I) with no signs of infiltration. The mass breached the cortex without infiltrating the overlying soft tissue. Microscopically, a hypocellular neoplasm with an infiltrative pattern of growth was observed. The stroma consisted of collagen-producing spindle cells with slight cytologic atypia and occasional mitotic figures. MIB-1 was expressed in less than 10% of the tumor cells. Upon careful microscopic examination of multiple sections, focal osteoid production was noted. The latter was eosinophilic, curvilinear, with small nubs, abortive lacunae formation and atypical neoplastic cells. There was no osteoblastic rimming. Based on the morphological features described allied to the clinical findings, the diagnosis of low-grade central osteosarcoma was made although characters of a fibrous dysplasia were apparent (Figure 5). Postoperatively, although the lesion was excised with healthy margin, preventive radiation of 60 Gy was finally delivered to the site.

After 7 years follow-up, the patient was apparently disease-free with no signs of implant mobility. Bone-scan imaging was performed annually following the surgery, with no signs of metastasis. The patient’s overall condition is very good with no ambulatory problems. However, there are frequent recurrences of subcutaneous and skin infection at the distal femur (a potential side-effect of radiotherapy secondary to the operation). This responded to antibiotics, requiring intravenous administration on two occasions. Limited range of motion to full extension and 40 degrees of flexion has developed postoperatively. This has responded well to physiotherapy including continuous passive motion assistance.

Since the first description of the low-grade central osteosarcoma, only a few case reports and fewer case series have been published in the literature[2,3,8-10]. The very low incidence of LGCO means that identifying the condition based on either the clinical, imaging or histological features of this tumour is complex. Moreover, the minimal cytological atypia, with the very low mitotic activity usually resembles more benign tumours. Differentiation from other conditions particularly fibrous dysplasia is complicated. Other conditions resembling this LGCO include ossifying or non-ossifying fibroma, aneurysmal bone cyst, or chondromyxoid fibroma or even malignant tumours such as parosteal osteosarcoma[3-5,10-23].

The clinical presentation on LGCO is heterogeneous usually manifesting as long-standing pain ranging from months to even several years before medical consultation is sought[8,24-26]. Mass, swelling or pathological fractures are rarely observed at the first admission[15].

There is also a highly variable radiographic appearance in LGCO[2,3,8,15,20]. The condition usually appears as a large medullary tumour often with trabeculation and sclerosis, with no periosteal new bone formation or soft tissue extension; it is thus easily mistaken for a benign lesion[8,10]. However, a potential cortical interruption due to localized destruction and soft tissue mass are the most typical radiographic findings leading to diagnosis[3,4,11]. It is believed that careful evaluation usually reveals at least a small region showing with cortical perforation, soft tissue shadows, or calcification, as well as periosteal reaction that should strengthen a suspicion of malignancy[6-8,15]. Nevertheless, 27 of the 90 patients in the Andresen et al[3] series show no aggressive features on the x-ray that could lead to a diagnosis of malignancy.

Andresen et al[3] described four radiographic patterns; a lytic with varying amounts of thick and coarse trabeculation, a predominantly lytic with few thin and incomplete trabecula, a densely sclerotic, and a mixed lytic and sclerotic subtype. It seems that radiographic appearance of a LGCO may evolve over a period of time. Our patient first appeared with a lytic lesion with varying trabeculation (Figure 1), while one month later it had altered into a mixed lytic and sclerotic lesion (Figure 2). The final image three months after the initial diagnosis was, however, clearly suggestive of the predominantly lytic pattern (Figure 3).

LGCO with sclerosis and lysis juxtaposed on the X-ray predisposes to a high incidence of misdiagnosis as this pattern is considered to radiographically mimic fibrous dysplasia in its morphology and matrix pattern[3]. The lesion usually extends to the end of the affected long bone, as found in 25 of 59 cases of Andersen series[3]. It usually reaches the subchondral bone without affecting the articular cartilage, as was also seen in the present case.

Although biopsy usually leads to the diagnosis, in the case of LGCO histology may be misleading, as arose in the present case. Inwards describes three main histological patterns of bone production, classifying the LGCO into three types: the fibrous dysplasia-like, the parosteal osteosarcoma-like and the desmoid-like[15]. In the fibrous dysplasia-like pattern, irregularly shaped spicules of woven bone are found even mimicking the classic “Chinese letters” pattern of fibrous dysplasia[10]. In that case misdiagnosis is likely and only further biopsy or radiographic findings may prevent it. The other two patterns also have histological features typically resembling parosteal osteosarcoma or desmoids tumour.

Seemingly benign features from either the clinical examination or the imaging or histological evaluation commonly lead to a misdiagnosis of LGCO. Choong et al[8] report a series of 20 cases of LGCO, 9 of each were initially misdiagnosed; one as chondrosarcoma while the other eight as benign lesions including fibrous dysplasia (3), nonossifying fibroma (2), fibroma (1), chondromyxoid fibroma (1) and simple bone cyst. Other tumours have also been diagnosed instead of LGCO, such as giant cell tumours, aneurysmal bone cysts, chondromyxoid fibromas, parosteal osteosarcomas or a malignant lymphoma[2,6,7,11,25].

There is agreement in the literature that wide excision is the only accepted treatment of LGCO, providing a very good prognosis. Wide excision is almost never followed by recurrence[6-8]. On the other hand, there is high incidence of local recurrence after inadequate surgical margins as with local excision of the tumour; this situation is highly likely to present with greater soft tissue and bony involvement. Recurrences are very often found to exhibit a higher histologic grade or dedifferentiation with the potential for metastases[14,15,27]. In the Mayo clinic series a 15% of the recurrences appeared as conventional osteosarcoma with poor prognosis[6]. Unni et al[2] report a high risk of transformation to conventional osteosarcoma if the lesion is initially treated only with curettage.

Choong et al[8] also report that an intralesional resection in 12 patients was associated with local recurrence to all of them. Four of the 12 recurrences were of a higher grade (25%), and 3 of these patients died of their disease. One was histologically undifferentiated. The time of the recurrence varies with a median period of 3 years, ranging from 3 months to even 14 years as found in one patient. Kurt et al[6] report two patients with initial diagnosis of fibrous dysplasia and long term recurrence following initial treatment with curettage. Both these patients eventually developed high-grade osteosarcoma 15 and 20 years after their initial curettage.

Distal metastases are rarely found from a LGCO but are more in keeping with a high-grade conventional osteosarcoma. Time of appearance varies with reported recurrence ranging from some months to several years after diagnosis[6,8]. Metastases can be pulmonary, osseous or to the lymph nodes[8]. It is the metastatic tumour from the higher-grade recurrence that can lead to death in patients with a low-grade central osteosarcoma[6,8,15].

A local recurrence with a higher clinical grade or signs of dedifferentiation, even if no metastases are apparent, is the only indication for adjuvant chemotherapy[6,8,11]. More aggressive forms of treatment such as amputation should not be required nowadays, with rare exceptions such as in the case of a diffuse tumor dedifferentiated to a high grade conventional osteosarcoma[8]. Radiotherapy is not generally mentioned in the literature as a treatment option for LGCO. However, in our case it was used due to the wide extension of the tumor in order to ensure the sterilization of the excision borders. It is nonetheless agreed that the treatment of low-grade central osteosarcoma is en-bloc resection with wide surgical margins, supported by the few published reports of prolonged follow-up.

LGCO is a rarely-encountered malignant tumour of the bones. Histologically it is a subtype of osteosarcoma, though with a much more favourable clinical outcome if treated appropriately. The typically late first diagnosis and the increased size of the initially found tumour, apparent with the low rate of recurrence or metastases, indicate its relatively benign progression. Nevertheless, its similarity to benign tumours and especially to fibrous dysplasia makes LGCO an insidious tumour, very often misdiagnosed and thus undertreated. The fibrous dysplasia-like histological pattern and the mixed lytic and sclerotic radiological pattern of LGCO are more likely to resemble fibrous dysplasia leading to misdiagnosis. An in-depth understanding of the histological features and its correlation to radiological and also clinical findings is instrumental in correct diagnosis.

Despite the extremely high incidence of misdiagnosis of a LGCO, very few specific diagnostic features have been described. However, lasting recent years there has been significant progress in identifying tools that will help the attending physician to correctly diagnose the type of lesion raising suspicion of its potential malignancy. Heat shock proteins (HSPs) for instance are known to overexpress in several tumours, and the HSP27 and HSP70 subtypes seem to allow discrimination between conventional and low-grade central osteosarcoma[28]. More interestingly, advances in immunohistochemistry and the understanding of chromosomal expression in sarcomas through the CDK4 and MDM2 proteins can facilitate safe differential diagnosis of a benign fibrous or fibro-osseous lesion rather than a low-grade osteosarcoma with its attendant requirement for appropriate surgical treatment[29,30]. Yoshida et al[29] report a very high percentage of sensitivity and specificity for the determination of low-grade osteosarcoma.

Nevertheless, detailed knowledge of the behaviour of this tumour remains the cornerstone of early diagnosis and appropriate treatment. A high level of suspicion should be held for any lesion in the metaepiphyseal region of a long bone with radiological findings suggesting malignancy, even in the presence of a benign histological diagnosis. In this instance LGCO should still be definitively excluded[3].

Additionally, the incidence of late recurrence or metastases, even up to 20 years after the excision of the tumour, makes long-term follow up important in order to ensure a long-term survival.

We would like to thank Padhraig S Fleming for expert language editing.

P- Reviewers Chen YK, Datta NS, Grote S, Schoffl V S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Wang CH

| 1. | Inward CY. Low-grade central osteosarcoma versus fibrous dysplasia. Pathol Case Rev. 2001;6:22-27. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Unni KK, Dahlin DC, McLeod RA, Pritchard DJ. Intraosseous well-differentiated osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1977;40:1337-1347. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Andresen KJ, Sundaram M, Unni KK, Sim FH. Imaging features of low-grade central osteosarcoma of the long bones and pelvis. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33:373-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Campanacci M, Bertoni F, Capanna R, Cervellati C. Central osteosarcoma of low grade malignancy. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1981;7:71-78. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sundaram M, Herbold DR, McGuire MH. Case report 370: Low grade (well-differentiated) intramedullary osteosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1986;15:338-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kurt AM, Unni KK, McLeod RA, Pritchard DJ. Low-grade intraosseous osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1990;65:1418-1428. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Bertoni F, Bacchini P, Fabbri N, Mercuri M, Picci P, Ruggieri P, Campanacci M. Osteosarcoma. Low-grade intraosseous-type osteosarcoma, histologically resembling parosteal osteosarcoma, fibrous dysplasia, and desmoplastic fibroma. Cancer. 1993;71:338-345. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Choong PF, Pritchard DJ, Rock MG, Sim FH, McLeod RA, Unni KK. Low grade central osteogenic sarcoma. A long-term followup of 20 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;198-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Schmitt H, Werner M, Sabo D, Bernd L, Delling G, Ewerbeck V. Low-grade central osteosarcoma. 3 case reports. Orthopade. 2002;31:208-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Muramatsu K, Hashimoto T, Seto S, Gondo T, Ihara K, Taguchi T. Low-grade central osteosarcoma mimicking fibrous dysplasia: a report of two cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:11-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Ellis JH, Siegel CL, Martel W, Weatherbee L, Dorfman H. Radiologic features of well-differentiated osteosarcoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151:739-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Franceschina MJ, Hankin RC, Irwin RB. Low-grade central osteosarcoma resembling fibrous dysplasia. A report of two cases. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1997;26:432-440. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Franchi A, Bacchini P, Della Rocca C, Bertoni F. Central low-grade osteosarcoma with pagetoid bone formation: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:288-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Iemoto Y, Ushigome S, Fukunaga M, Nikaido T, Asanuma K. Case report 679. Central low-grade osteosarcoma with foci of dedifferentiation. Skeletal Radiol. 1991;20:379-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Inward CY, Knuutila S. Low grade central osteosarcoma. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press 2002; 275-276. |

| 16. | Park YK, Yang MH, Choi WS, Lim YJ. Well-differentiated, low-grade osteosarcoma of the clivus. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24:386-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sim FH, Kurt AM, McLeod RA, Unni KK. Case report 628: Low-grade central osteosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1990;19:457-460. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Xipell JM, Rush J. Case report 340: Well differentiated intraosseous osteosarcoma of the left femur. Skeletal Radiol. 1985;14:312-316. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Yamaguchi T, Shimizu K, Koguchi Y, Saotome K, Ueda Y. Low-grade central osteosarcoma of the rib. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:490-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bonar SF. Central low-grade osteosarcoma: a diagnostic challenge. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:365-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Malhas AM, Sumathi VP, James SL, Menna C, Carter SR, Tillman RM, Jeys L, Grimer RJ. Low-grade central osteosarcoma: a difficult condition to diagnose. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:764796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Endo M, Yoshida T, Yamamoto H, Ishii T, Setsu N, Kohashi K, Matsunobu T, Iwamoto Y, Oda Y. Low-grade central osteosarcoma arising from bone infarct. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1184-1189. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Takagi S, Seo H, Aoki M, Nabeshima K, Naito M. Low-grade central osteosarcoma of the metatarsal bone: a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic analysis. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:5429-5435. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Barbera C, Tornetta P, Vigorita VJ, Zilles M, Etienne G. Leg pain in an 11-year-old boy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;264-270, 270-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ostrowski ML, Johnson ME, Smith PD, Chevez-Barrios P, Spjut HJ. Low-grade intraosseous osteosarcoma with prominent lymphoid infiltrate. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:868-871. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Song SH, Lee H, Song HR, Kim MJ, Park JH. Fibrocartilaginous intramedullary bone forming tumor of the distal femur mimicking osteosarcoma. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:631-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ogose A, Hotta T, Emura I, Imaizumi S, Takeda M, Yamamura S. Repeated dedifferentiation of low-grade intraosseous osteosarcoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:615-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Moon A, Bacchini P, Bertoni F, Olvi LG, Santini-Araujo E, Kim YW, Park YK. Expression of heat shock proteins in osteosarcomas. Pathology. 2010;42:421-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yoshida A, Ushiku T, Motoi T, Shibata T, Beppu Y, Fukayama M, Tsuda H. Immunohistochemical analysis of MDM2 and CDK4 distinguishes low-grade osteosarcoma from benign mimics. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1279-1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Dujardin F, Binh MB, Bouvier C, Gomez-Brouchet A, Larousserie F, Muret Ad, Louis-Brennetot C, Aurias A, Coindre JM, Guillou L. MDM2 and CDK4 immunohistochemistry is a valuable tool in the differential diagnosis of low-grade osteosarcomas and other primary fibro-osseous lesions of the bone. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:624-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |