Published online Jan 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i1.97848

Revised: October 28, 2024

Accepted: December 25, 2024

Published online: January 18, 2025

Processing time: 216 Days and 9.9 Hours

Demineralized bone matrix (DBM) is a commonly utilized allogenic bone graft substitute to promote osseous union. However, little is known regarding out

To evaluate the clinical and radiographic outcomes following DBM as a biological adjunct in foot and ankle surgical procedures.

During May 2023, the PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane library databases were systematically reviewed to identify clinical studies examining outcomes following DBM for the management of various foot and ankle pathologies. Data regarding study characteristics, patient demographics, subjective clinical outcomes, radio

In total, 363 patients (397 ankles and feet) received DBM as part of their surgical procedure at a weighted mean follow-up time of 20.8 ± 9.2 months. The most common procedure performed was ankle arthrodesis in 94 patients (25.9%). Other procedures performed included hindfoot fusion, 1st metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis, 5th metatarsal intramedullary screw fixation, hallux valgus correction, osteochondral lesion of the talus repair and unicameral talar cyst resection. The osseous union rate in the ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis cohort, base of the 5th metatarsal cohort, and calcaneal fracture cohort was 85.6%, 100%, and 100%, respectively. The weighted mean visual analog scale in the osteochondral lesions of the talus cohort improved from a pre-operative score of 7.6 ± 0.1 to a post-operative score of 0.4 ± 0.1. The overall complication rate was 27.2%, the most common of which was non-union (8.8%). There were 43 failures (10.8%) all of which warranted a further surgical procedure.

This current systematic review demonstrated that the utilization of DBM in foot and ankle surgical procedures led to satisfactory osseous union rates with favorable wound complication rates. Excellent outcomes were observed in patients undergoing fracture fixation augmented with DBM, with mixed evidence supporting the routine use of DBM in fusion procedures of the ankle and hindfoot. However, the low LOE together with the low QOE and significant heterogeneity between the included studies reinforces the need for randomized control trials to be conducted to identify the optimal role of DBM in the setting of foot and ankle surgical procedures.

Core Tip: Despite the prevalent use of demineralized bone matrix in foot and ankle surgeries, this systematic review uncovers a lack of robust evidence supporting its efficacy. While it demonstrates satisfactory osseous union rates and favorable complication profiles, the insufficiency of high-quality studies and significant heterogeneity across research call for caution in its clinical application, emphasizing the need for further well-designed investigations to establish its effectiveness definitively.

- Citation: Hartman H, Butler JJ, Calton M, Lin CC, Rettig S, Tishelman JC, Krebsbach S, Randall GW, Kennedy JG. Limited evidence to support demineralized bone matrix in foot and ankle surgical procedures: A systematic review. World J Orthop 2025; 16(1): 97848

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i1/97848.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i1.97848

Bone grafting is a frequently utilized procedure in foot and ankle surgery, particularly in the setting of fusion procedures and displaced fractures to promote osseous union[1]. The current gold standard grafting material is autologous cortico-cancellous bone graft, which is typically harvested from the ipsilateral iliac crest[1]. Autologous bone graft is an attractive adjunct in arthrodesis and fracture fixation due to its osteoinductive, osteoconductive and minimal osteogenic properties. However, autologous bone grafting is limited by the high donor site morbidity (8%-39%) in addition to the variable available bone stock[2]. In light of the drawbacks associated with autologous bone grafting, novel allogenic bone graft substitutes have been developed.

Demineralized bone matrix (DBM) is a pre-packaged allogenic bone graft substitute produced following extensive decalcification in addition to radiation procedures to minimize the risk of infection and potential immunogenic response[3]. DBM consists of an osteoconductive collagen-based scaffold and various bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) which potential[4]. DBM has gained popularity in the field of orthopedic surgery with an exponentially increasing number of DBM products becoming commercially available on the market over the last number of years due to favorable regulatory pathways allowing rapid delivery to the market[3].

In foot and ankle surgery, DBM has been utilized in ankle arthrodesis, hindfoot fusion procedures, midfoot arthrodesis procedures and fracture fixation with variable osseous union rates reported in the literature[5-14]. However, there has been no consensus regarding its effect on osseous union rates and complication rates.

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate clinical and radiographic outcomes following DBM as a biological adjunct in surgical procedures of the foot and ankle.

During May 2023, utilizing the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE & EMBASE databases, a systematic review was undergone based on the PRISMA guidelines[15]. The following search terms were used: [(Demineralized and bone and matrix) or (DBM)] and (foot or ankle or talus or talar or metatarsal or hindfoot or midfoot). Both the inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| At least 1 year follow-up | Less than 1 year follow-up |

| Human participants | Cadaver or animal studies |

| Minimum 5 patients per cohort | Less than five patients per cohort |

| Outcomes following demineralized bone matrix for foot and ankle surgical procedures | Systematic reviews or case reports |

| Written in English | Written in foreign language |

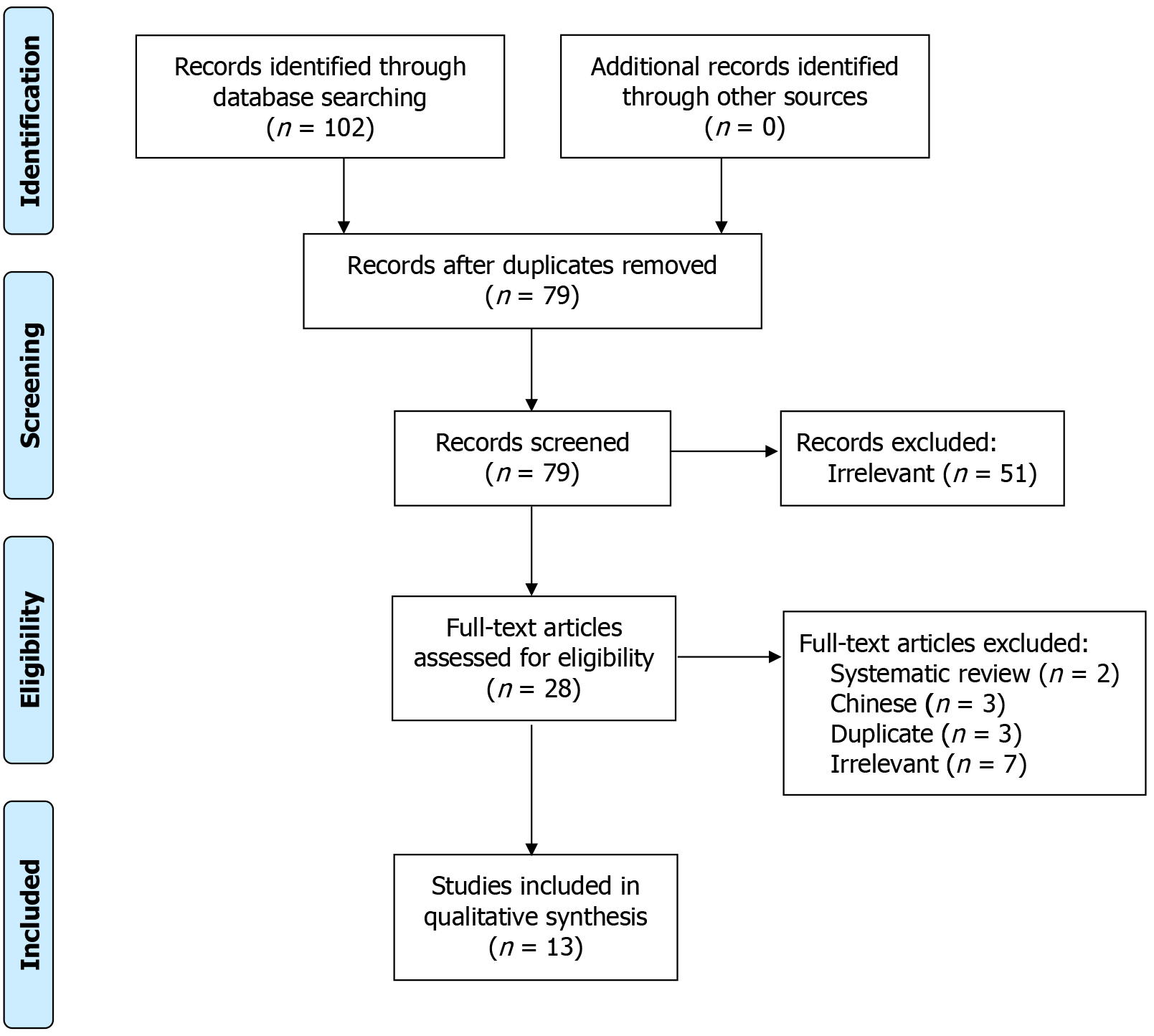

With 191 articles originally identified, there were 36 duplicates, and 22 were not in English. This left 133 articles to be screened by 2 independent reviewers. Articles were included if they were based on human patients, had a minimum of 5 patients, and if they were examining outcomes following surgical treatment of foot and ankle pathologies augmented with DBM. The minimum study threshold of 5 patients was set to allow for the inclusion of studies with sufficient sample diversity while avoiding case reports and minimizing intra-study variability. This left 13 studies to be analyzed.

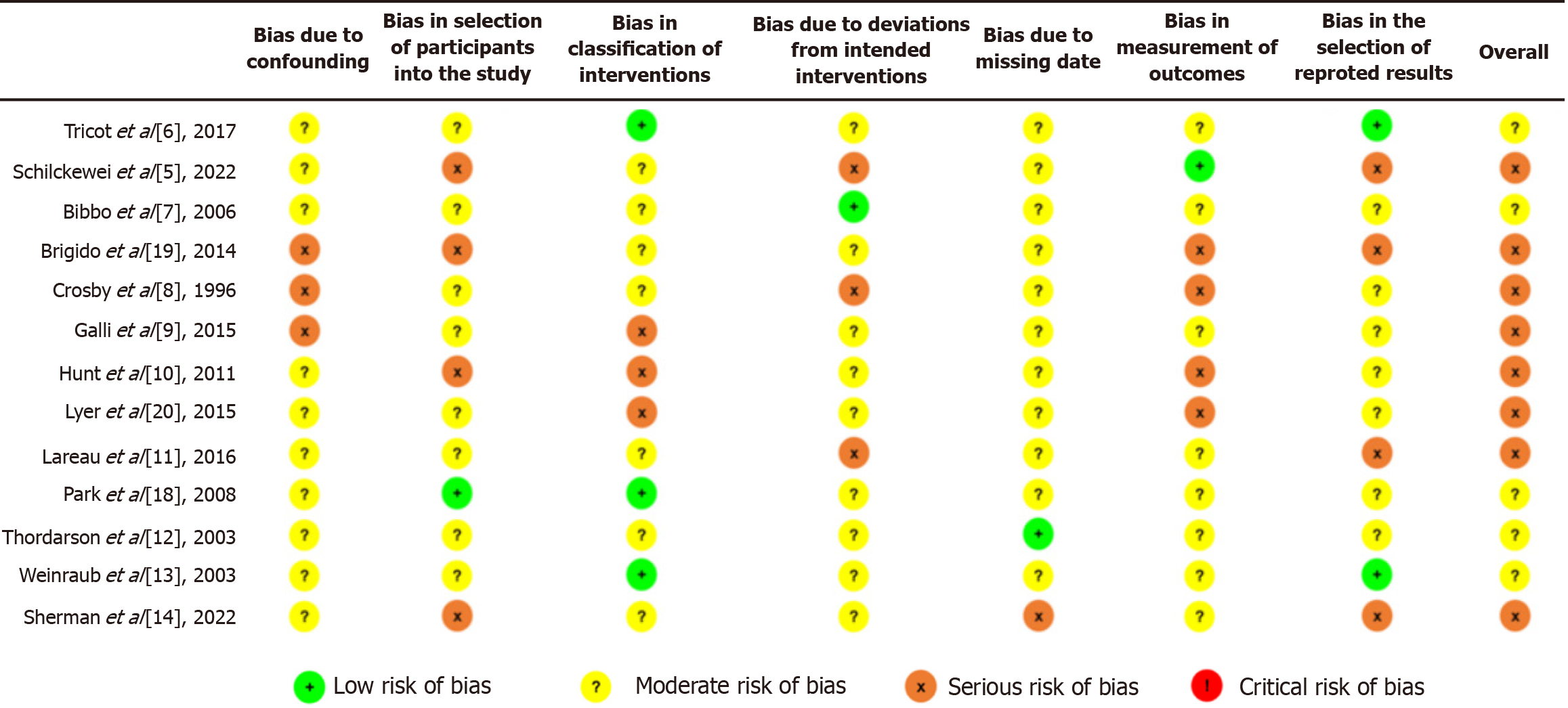

The level of evidence (LOE) was assessed according to the guidelines published by The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery[16]. The Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies-of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was utilized to complete assessment of the quality of clinical evidence and risk of bias for non-randomized studies (Figure 1)[17]. There were 7 domains within this tool, of which the first 2 address potential confounders and study participant selection. The third domain addresses classification of interventions, and the other 4 domains evaluate bias due to deviation from described interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and reported result selection. There is a final domain that provides an overall assessment of the study. Each domain has a risk-of-bias judgement set at ‘low’, ‘moderate’, ‘serious’, or ‘critical’ risk of bias, with an option of ‘no information’ as well.

The data from each study was extracted and assessed by two independent reviewers. Data on both the patient demographic and the characteristics of the surgical procedures were collected. Clinical and subjective outcomes, radiological parameters, union, complications, failures, and requirement for further procedures were evaluated.

All other statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary NC). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all continuous and categorical variables. Continuous variables were reported as weighted mean and estimated standard deviation, whereas categorical variables were reported as frequencies with percentages.

The search generated 191 studies (Figure 2). Only 13 of these met the inclusion and exclusion criteria of this systematic review. These studies were published between 1996 and 2022. Twelve of these studies were published within the past 20 years, and eight studies (61.5%) were published within the past 10 years.

Study characteristics and patient demographics are listed in Table 2. Five studies[6,7,12,13,18] were LOE III, and 8 studies[5,8-11,14,19,20] were LOE IV. No studies were classified as excellent quality using the ROBINS-I. According to ROBINS-I, there were 0 studies of low risk of bias, 5 studies of moderate risk, and 8 studies with serious risk (Figure 1).

| Ref. | LOE | Patients (N) | Ankles/Hindfoot/Joints (N) | Follow up (months) | Age | M/F | R/L | Surgical procedure | DBM utilized | DBM volume (cc) |

| Tricot et al[6] | 3 | 30 | 45 | 17 | 56.5 | 16/14 | n/r | TT arthrodesis = 6, TT + ST arthrodesis = 11, ST arthrodesis = 8, ST + TN arthrodesis = 2, ST + TN + CC arthrodesis = 2, CC arthrodesis = 0, TT + ST + TN + CC arthrodesis = 1 | DBM was supplied by the tissue bank at the Saint-Luc University Clinic in Brussels and made from allogenic cortical bone | 6 |

| Tricot et al[6] | 3 | 52 | 70 | 12.5 | 56 | 27/27 | n/r | TT arthrodesis = 9, TT + ST arthrodesis = 8, ST arthrodesis = 19, ST + TN arthrodesis = 6, ST + TN + CC arthrodesis = 6, CC arthrodesis = 2, TT + ST + TN + CC arthrodesis = 2 | DBM was supplied by the tissue bank at the Saint-Luc University Clinic in Brussels and made from allogenic cortical bone | 9 |

| Schlickewei et al[5] | 4 | 31 | 31 | 43 | 58.2 | 10/21 | 16/15 | Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis = 31 | DBX Inject (Depuy Synthes, Solothurn, Switzerland) | 2-5 |

| Bibbo and Patel[7] | 3 | 33 | 33 | 22.4 | 42.2 | 23/10 | 20/13 | Calcaneal fracture ORIF = 31 | Allomatrix (Wright Medical, Arlington, TN) | 5-10 |

| Brigido et al[19] | 4 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 43.2 | 6/7 | 10/3 | Demineralized subchondral allograft = 13 | SC Plug (Bacterin International, Belgrade, MT) | n/r |

| Crosby and Fitzgibbons[8] | 4 | 42 | 42 | 27 | 46 | 25/16 | n/r | Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis = 42 | n/r | n/r |

| Galli et al[9] | 4 | 12 | 12 | 24 | 43.9 | 5/7 | 9/3 | Demineralized Allograft Subchondral Bone = 12 | OsteoSponge SC (Bacterin, MT) | n/r |

| Hunt and Anderson[10] | 4 | 8 | 8 | 27.3 | 27 | 6/2 | 2/6 | Intramedullary screw fixation for Jones fracture = 8 | Ignite (Wright Medical, Arlington, TN) | 1-2 |

| Hunt and Anderson[10] | 4 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 15 | 0/1 | 0/1 | Intramedullary screw fixation for Jones fracture = 1 | Ignite (Wright Medical, Arlington, TN) | 1-2 |

| Iyer et al[20] | 4 | 17 | 17 | 28.8 | 47.7 | 3/14 | 8/9 | Akin osteotomy = 10, Second hammertoe correction = 6, Medial sesamoidectomy = 1 | Bonus DBM (Biomet, IN) | n/r |

| Lareau et al[11] | 4 | 25 | 25 | 6 | 24 | 25/0 | 10/15 | Intramedullary screw fixation for Jones fracture = 25 | Mini-Ignite (Wright Medical, Arlington, TN) | n/r |

| Park et al[18] | 3 | 9 | 10 | 33.7 | 18.9 | 6/3 | 3/5 | Cyst debridement and resection = 10 | Injecta Bone TR (Modumedi Ltd., Daegu, Korea) | n/r |

| Thordarson and Latteier[12] | 3 | 37 | 37 | 12 to 78 | 50.8 | 17/20 | n/r | TT arthrodesis = 5, ST arthrodesis = 6, ST + TN + CC arthrodesis = 20, CC arthrodesis = 1, TT + ST + TN + CC arthrodesis = 1, TTC arthrodesis = 3, TT + CC arthrodesis = 1 | Grafton Putty (Osteotech, NJ) | n/r |

| Thordarson and Latteier[12] | 3 | 26 | 26 | 12 to 78 | 49.9 | 12/14 | n/r | TT arthrodesis = 1, ST arthrodesis = 6, ST + TN + CC arthrodesis = 14, CC arthrodesis = 0, TT + ST + TN + CC arthrodesis = 1, TTC arthrodesis = 4, TT + CC arthrodesis = 0 | Orthoblast (SeaSpine, CA) | n/r |

| Weinraub and Cheung[13] | 3 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 62 | n/r | n/r | TN + ST + CC arthrodesis = 1 | n/r (MTF, NJ) | n/r |

| Weinraub and Cheung[13] | 3 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 43.9 | n/r | n/r | TN arthrodesis = 1, MCJ arthrodesis = 4, Evans osteotomy = 1, Evans + Cotton osteotomy = 1, ST arthrodesis = 2, 1st MTPJ arthrodesis = 1, ST + NC + 1st MTPJ arthrodesis = 1 | n/r (MTF, NJ) | n/r |

| Sherman et al[14] | 4 | 14 | 14 | 22.6 | 52.1 | 5/9 | n/r | TTC arthrodesis augmented with fresh-frozen femoral head allograft, cBMA, DBM = 14 | n/r | n/r |

From the 13 studies, 363 patients (397 ankles and feet), with a weighted mean age of 52.4 ± 14 years (range 15-62), received DBM as part of their surgical procedure. The weighted mean follow-up time was 20.8 ± 9.2 months (range 6-78). Of the 363 patients, 187 were male (53.1%) and 165 were female (46.9%). Amongst the 397 ankles and feet, 8 articles included which foot was operated on, of which 78 were right ankles, and 70 were left ankles. The weighted mean body mass index across 6 studies was 26.8 ± 3 kg/m2 (range 27.6-36.8). Of the 363 patients, 5 studies included data on smoking history, of which 48 patients (13.2%) had a history of smoking. Five studies reported data on diabetes, of which 10 patients (2.75%) were diabetic.

Eleven different formulations of DBM were utilized across the 13 studies including DBX Inject (Depuy Synthes, Solothurn, Switzerland), Allomatrix (Wright Medical, Arlington, TN), SC Plug (Bacterin International, Belgrade, MT), OsteoSponge SC (Bacterin International, MT), Ignite (Wright Medical, Arlington TN), Bonus DBM (Biomet, IN), Mini-Ignite (Wright Medical, Arlington, TN), Grafton Putty (Osteotech, NJ), Orthoblast (GenSci, CA), DBM sourced from Medical Transplantation Foundation (NJ), Injecta Bone TR (Modumedi Ltd., Daegu, Korea) and DBM sourced locally by the tissue bank at the Saint-Luc University Clinic in Brussels. All DBM formulations compiled in this systematic review are bone-derived, osteoconductive, and possibly, osteoinductive; however, variability in commercial supplier’s preparation methods may introduce difference in product efficacy, which should be considered when generalizing these conclusions.

In 6 studies[5,6,8,12-14], 245 patients (278 ankles and feet) underwent fusion procedures of the foot and/or ankle at a weighted mean follow-up time of 24.2 ± 11.9 months (range, 10-43).

No pre-operative nor post-operative patient reported outcome measurements (PROMs) were recorded.

All 6 studies reported data concerning osseous union (Table 3). In total, 238 ankles and feet (85.6%) achieved osseous union. There were 32 (11.5%) who non-unions, 2 (0.72%) delayed unions and 8 (2.9%) fibrous unions.

| Ref. | Patients (N) | Ankles/Hindfoot/Joints (N) | Union (%) | Non-union (%) | Complications | Failures | Secondary procedures |

| Tricot et al[6] | 30 | 45 | 37 (82.2) | 8 (17.8) | Nonunion = 8, heterotopic ossification = 2 | 11 | Repeat procedure = 11 |

| Tricot et al[6] | 52 | 70 | 62 (88.6) | 8 (11.4) | Nonunion = 8, heterotopic ossification = 4, infection = 3 | 10 | Repeat procedure = 10 |

| Schlickewei et al[5] | 31 | 31 | 27 (87.1) | 4 (12.9) | Nonunion = 4, superficial wound infection = 2, symptomatic hardware = 6 | 9 | Revision arthrodesis due to nonunion = 3, hardware removal = 6 |

| Bibbo and Patel[7] | 33 | 33 | 33 (100) | 0 (0) | Incisional nonhealing = 5, full-length wound dehiscense = 1, skin sloughing = 1 | n/r | n/r |

| Brigido et al[19] | 13 | 13 | n/r | n/r | DVT = 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Crosby and Fitzgibbons[8] | 42 | 42 | 31 (73.8) | 3 (7) | Nonunion = 3, delayed union = 2, infection = 5, symptomatic hardware = 10, stress fracture = 2, progressive symptomatic subtalar arthritis = 4, guide pin shear = 1 | n/r | Hardware removal = 4, open procedure = 1, electrical stimulation = 1, debridement = 1 |

| Galli et al[9] | 12 | 12 | n/r | n/r | DVT = 1 | 0 | n/r |

| Hunt and Anderson[10] | 8 | 8 | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | n/r |

| Hunt and Anderson[10] | 1 | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | n/r |

| Iyer et al[20] | 17 | 17 | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | Symptomatic hardware = 2, Arthritis = 3, 2nd toe hammering = 1, stiffness = 1, MTPJ pain = 3, prominent hardware = 1 | 11 | Modified lapidus = 4, hardware removal = 2 |

| Lareau et al[11] | 25 | 25 | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 | n/r | n/r |

| Park et al[18] | 9 | 10 | n/r | n/r | Residual defect = 5, Healed cyst = 5 | n/r | n/r |

| Thordarson and Latteier[12] | 37 | 37 | 32 (86.5) | 5 (13.5) | Nonunion = 5 | 5 | n/r |

| Thordarson and Latteier[12] | 26 | 26 | 24 (92.3) | 2 (7.7) | Nonunion = 2 | 2 | n/r |

| Weinraub and Cheung[13] | 1 | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | Nonunion = 1 | 1 | n/r |

| Weinraub and Cheung[13] | 12 | 12 | 12 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | n/r |

| Sherman et al[14] | 14 | 14 | 13 (92.9) | 1 (7.1) | Nonunion = 1, infection = 1 | 1 | n/r |

There were 79 complications (28.4%) reported, the most common of which was non-union in 32 patients (11.5%). Other complications included 2 patients (0.72%) with delayed union, 6 patients (2.2%) with heterotopic ossification, 16 patients (5.8%) with wound complications, 15 patients (5.4%) with hardware failure, 2 patients (0.72%) with stress fracture, and 4 patients (1.4%) with progressive subtalar arthritis. Of the 16 patients (5.8%) with wound complications, 14 patients (5.0%) had data reported on concomitant non-unions[6,7,8,14]. There were 2 reported non-unions (14.3%) among patients who had wound complications[6,14].

In total, 37 patients (13.3%) underwent secondary surgical procedures, the most common of which was arthrodesis in 22 patients (7.9%).

In 2 studies[10,11], 34 patients (34 feet), underwent intramedullary screw fixation of fractures of the base of the 5th metatarsal augmented with DBM at a weighted mean follow-up time of 20.8 ± 8.3 months (range, 12-27.3). No pre-operative nor post-operative PROMs were recorded. All 2 studies reported data concerning osseous union. In total, all 34 patients (100%) achieved osseous union. No complications, failures nor secondary surgical procedures were reported.

In 1 study[7], 33 patients (33 ankles) underwent open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) for the management of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures at a mean follow-up time of 29 months. No pre-operative nor post-operative PROMs were recorded. All 33 patients (100%) achieved osseous union. There were 5 (15.2%) complications reported, all of which were incisional wound complications.

In 2 studies[9,19], 25 patients (25 feet), underwent treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus (OLT) at a weighted mean follow-up time of 17.8 ± 8.5 months (range, 12-24). No pre-operative nor post-operative PROMs were recorded. In addition, no post-operative radiographic nor magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging was reported. There were 2 complications (8%) reported, both of which were deep vein thromboses. There were no secondary surgical procedures or failures reported.

In 1 study[20], 17 patients (17 feet), underwent correction of hallux valgus deformity. The follow-up time was 28.8 months. No pre-operative nor post-operative PROMs were recorded. There were 12 complications (64.7%), primarily related to symptomatic hardware in 4 patients (23.5%), arthritis in 3 patients (17.6%), second toe hammering (5.9%), and first metatarsal pain/stiffness in 4 patients (23.5%). In total, 6 patients (35.3%) underwent secondary surgical procedures, of which 4 patients (23.5%) underwent a modified Lapidus procedure, and 2 patients (11.8%) underwent hardware removal. In total, there were 11 failures (70.6%) reported, all of which experienced recurrence of the originally deformity.

In 1 study[18], 9 patients (10 feet) underwent treatment of a unicameral bone cyst at a mean follow-up time of 33.7 months. No pre-operative nor post-operative PROMs were recorded. There were 2 complications (20%) reported, all due to painless persistent cystic defect. There were no secondary surgical procedures or failures reported.

The most important finding of this current systematic review was the use of DBM in foot and ankle surgical procedures led to satisfactory osseous union rates with favorable complication rates. Excellent outcomes were observed in patients undergoing fracture fixation augmented with DBM, with mixed evidence supporting the routine use of DBM in fusion procedures of the ankle and hindfoot. However, the dearth of level I randomized control trials (RCTs) together with the low quality of evidence (QOE) and significant heterogeneity between the included studies limits the generation of any robust cross-sectional analysis.

There has a been a rapidly growing interest in the use of various biological adjuncts in orthopedic surgery in recent years, with purported benefits of increased union rates, lower infection rates, accelerated return to daily activities and no complications associated with donor site harvesting[21]. DBM has been proposed as an effective, if not superior alternative to autograft and allograft procedures in foot and ankle surgery. DBM was initially utilized in humans in 1889 who isolated DBM from oxen tibiae to treat long bone and cranial defects[22]. In 1965, Urist[23] were the first group to isolate human DBM to treat long bone and lumbar spine defects. Human DBM is isolated following decalcification using an acidic solution to isolate collagen (predominantly type I collagen, with trace amounts of type IV and X), non-collagen proteins, calcium phosphate, BMPs, transforming growth factor-β1 and insulin-like growth factor-1[3,21]. The insoluble collagen acts as a 3-dimensional osteoconductive scaffold for ingrowth of perivascular tissue, host capillaries and osteoprogenitor cells. The osteoinductive BMPs signal local mesenchymal stem cells to differentiate into osteoblasts and chondroblasts to promote new bone growth.

Outcomes following the utilization of DBM in the setting of foot and ankle surgery have not been well described to date. This systematic review found that DBM is most frequently used in various lower limb fusion procedures (51.8%), the most common of which was ankle arthrodesis (25.9%). Across 2 studies in this systematic review in which the data was accurately reported, there was a 79.5% fusion rate and an 9.6% non-union rate in the ankle arthrodesis cohort. A single arm retrospective case series by Crosby and Fitzgibbons[8] evaluated clinical and radiographic outcomes in 42 patients who underwent arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis using a bi-framed distraction technique augmented with DBM. The authors reported a 73.8% union rate, a 7% non-union rate and a 5.1% delayed union rate. Furthermore, a re

Non-union following hindfoot arthrodesis is a commonly encountered complication, with rates reported up to 41%[24]. In this current systematic review, DBM was utilized widely in hindfoot arthrodesis procedures (38.8%) in an effort to circumvent this challenging pathology. It was not possible to synthesize pooled union and non-union rates due to underreporting of the data across the studies. Tricot et al[6] conducted a retrospective comparative study evaluating outcomes between patients undergoing hindfoot arthrodesis and ankle arthrodesis who received autograft augmented with DBM compared to allograft augmented with DBM and cBMA. The authors reported similar fusion rates between the 2 cohorts, with a mean non-union rate of 15%. Furthermore, Sherman et al[14] reported a 90.9% fusion rate across 14 patients who underwent TTC arthrodesis augmented with DBM, cBMA and fresh-frozen femoral head allograft. Finally, Thordarson and Latteier[12] utilized various DBM products in both ankle and hindfoot fusion procedures, reporting a 10% non-union rate, which they described to be comparable to historical records.

This systematic review found that although DBM was a safe to utilize bone graft substitute, it did not provide superior osseous union rates in both ankle arthrodesis and hindfoot fusion procedures compared to those who did not receive DBM. While DBM may not confer any advantage with respect to union rates in younger, healthier patients with favorable biology, it may be an important biological adjunct in patients who are at risk of high donor site morbidity of autograft harvest such as the elderly. DBM has been shown to have a high osseous union rate of 83.9% in spinal fusion in the elderly who are at significant risk for graft donor site morbidities[25]. Similar studies in the elderly have yet to be performed for midfoot or hindfoot fusion procedures.

Three studies in this review utilized DBM in the management of traumatic fractures of the lower limb. Lareau et al[11], Hunt and Anderson[10] examined the use of DBM as a biological augment during screw fixation of fractures of the base of the 5th metatarsal in a cohort of 34 patients. All 34 patients (100%) achieved osseous union. Furthermore, Bibbo and Patel[7] examined outcomes following ORIF of calcaneal fractures augmented with DBM in 33 patients. All 33 patients (100%) achieved osseous union. Furthermore, 1 study in this review by Iyer et al[20] reported a 100% union rate following proximal medial closing wedge osteotomy for hallux valgus deformity. The osseous union rate reported in studies utilizing DBM as an adjunct in traumatic fractures of the lower limb closely resembles the rates of osseous union in surgical intervention of the calcaneus without the use of DBM. Adrian et al reported an osseous union rate of 96.8% in 31 patients receiving a minimally invasive calcaneal osteotomy[26], whereas Davis et al[27] reported a 100.0% osseous union rate in 33 patients treated with minimally invasive surgery for calcaneal fractures. This suggests that the excellent osseous union rates may not be entirely attributed to the addition of DBM as an augment.

OLT are difficult to treat pathologies in light of the poor regenerative capacity of the articular cartilage[28]. As a result, numerous biological adjuncts have been developed to address this debilitating pathology, including platelet-rich plasma, concentrated bone marrow aspirate and extracellular matrix cartilage allograft[28,29]. Two studies in this review investigated the effects of a cylindrical, malleable DBM to treat cystic OLTs that failed prior microfracture in a case series of 12 patients[9,19]. The authors reported significant improvement in subjective clinical outcomes at final follow-up, suggesting that DBM may be a valuable adjunct used to treat OLTs. However, these results must be interpreted with caution due to significant limitations with the study including the lack of utilization of a validated PROM, mean follow-up of 2 years and lack of post-operative MRI or arthroscopic evaluation of the reparative tissue.

Post-operative infections are a major source of morbidity in orthopedic surgery. Thus, a multitude of prophylactic measures have been devised to reduce the risk of wound complications including routine administration of prophylactic antibiotics, development of minimally invasive surgical techniques, utilization of bacteriocidal skin preparations, bacteriocidal wound irrigation, sterile draping, hoods, laminar airflow ventilation, ultraviolet lights, masks, helmet exhaust suits, and terminal room cleaning[30]. A proposed benefit of the use of DBM compared to autologous bone grafting is the potential lower infection rates due to the lack of donor site harvesting[7,21]. Overall, there was a 5.3% infection rate in this cohort, suggesting that DBM may be a potent strategy to mitigate against the development of wound related complications. In addition, DBM can be utilized as a vehicle for local antibiotic delivery to reduce the risk of infection. Bibbo and Patel[7] examined the rate of superficial and deep wound infections and the rate of osteomyelitis following the use of DBM combined with vancomycin powder in the management of 33 cases of calcaneal fractures. An overall infection rate of 15% was reported, all of which occurred in type III fractures. No cases of deep wound infections nor osteomyelitis were reported. Despite the litany of benefits associated with DBM, limitations with this allogenic bone graft exists. Disadvantages of DBM include low immunogenicity, which is vital for triggering a strong immune response to integrate the graft into the recipient site, variability in osteoinductive potential between products, inconsistency in surgeon handling of DBM products, variation in patient acceptance of grafting materials, high costs associated with certain DBM products and ethical challenges with regards to obtaining bone sources[31].

This systematic review has several inherent limitations. The criterion was limited to MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Library Database articles published exclusively in English. The included studies were of low QOE and primarily those of serious risk of bias, which introduces potential bias into this review. The data extraction process was carried out by 2 independent reviewers, rather than performed blindly, and later confirmed by the lead author. The studies in this review were extremely heterogenous, including varied conditions treated, surgical treatments performed, measurements reported, and DBM products utilized, limiting the ability to define precise indications for the use of DBM in foot and ankle surgical procedures.

This current systematic review demonstrated that the utilization of DBM in foot and ankle surgical procedures led to satisfactory osseous union rates with favorable complication rates. Excellent outcomes were observed in patients undergoing fracture fixation augmented with DBM, with mixed evidence supporting the routine use of DBM in fusion procedures of the ankle and hindfoot. However, the low LOE together with the low QOE and significant heterogeneity between the included studies reinforces the need for RCTs to be conducted to identify the optimal role of DBM in the setting of foot and ankle surgical procedures.

| 1. | Finkemeier CG. Bone-grafting and bone-graft substitutes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:454-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 728] [Cited by in RCA: 665] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Arrington ED, Smith WJ, Chambers HG, Bucknell AL, Davino NA. Complications of iliac crest bone graft harvesting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;300-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1064] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gruskin E, Doll BA, Futrell FW, Schmitz JP, Hollinger JO. Demineralized bone matrix in bone repair: history and use. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1063-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Urist MR, Dowell TA. Inductive substratum for osteogenesis in pellets of particulate bone matrix. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;61:61-78. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Schlickewei C, Neumann JA, Yarar-Schlickewei S, Riepenhof H, Valderrabano V, Frosch KH, Barg A. Does Demineralized Bone Matrix Affect the Nonunion Rate in Arthroscopic Ankle Arthrodesis? J Clin Med. 2022;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tricot M, Deleu PA, Detrembleur C, Leemrijse T. Clinical assessment of 115 cases of hindfoot fusion with two different types of graft: Allograft+DBM+bone marrow aspirate versus autograft+DBM. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103:697-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bibbo C, Patel DV. The effect of demineralized bone matrix-calcium sulfate with vancomycin on calcaneal fracture healing and infection rates: a prospective study. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:487-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Crosby LA, Fitzgibbons TC. Open reduction and internal fixation of type II intra-articular calcaneus fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:253-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Galli MM, Protzman NM, Bleazey ST, Brigido SA. Role of Demineralized Allograft Subchondral Bone in the Treatment of Shoulder Lesions of the Talus: Clinical Results With Two-Year Follow-Up. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2015;54:717-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hunt KJ, Anderson RB. Treatment of Jones fracture nonunions and refractures in the elite athlete: outcomes of intramedullary screw fixation with bone grafting. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1948-1954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lareau CR, Hsu AR, Anderson RB. Return to Play in National Football League Players After Operative Jones Fracture Treatment. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37:8-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Thordarson DB, Latteier M. Open reduction and internal fixation of calcaneal fractures with a low profile titanium calcaneal perimeter plate. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:217-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Weinraub GM, Cheung C. Efficacy of allogenic bone implants in a series of consecutive elective foot procedures. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2003;42:86-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sherman AE, Mehta MP, Nayak R, Mutawakkil MY, Ko JH, Patel MS, Kadakia AR. Biologic Augmentation of Tibiotalocalcaneal Arthrodesis With Allogeneic Bone Block Is Associated With High Rates of Fusion. Foot Ankle Int. 2022;43:353-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13930] [Cited by in RCA: 13358] [Article Influence: 834.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wright JG, Swiontkowski MF, Heckman JD. Introducing levels of evidence to the journal. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1-3. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham J, Jüni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schünemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JP. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7683] [Cited by in RCA: 10884] [Article Influence: 1209.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Park IH, Micic ID, Jeon IH. A study of 23 unicameral bone cysts of the calcaneus: open chip allogeneic bone graft versus percutaneous injection of bone powder with autogenous bone marrow. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29:164-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brigido SA, Protzman NM, Galli MM, Bleazey ST. The role of demineralized allograft subchondral bone in the treatment of talar cystic OCD lesions that have failed microfracture. Foot Ankle Spec. 2014;7:377-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iyer S, Demetracopoulos CA, Sofka CM, Ellis SJ. High Rate of Recurrence Following Proximal Medial Opening Wedge Osteotomy for Correction of Moderate Hallux Valgus. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36:756-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang H, Yang L, Yang XG, Wang F, Feng JT, Hua KC, Li Q, Hu YC. Demineralized Bone Matrix Carriers and their Clinical Applications: An Overview. Orthop Surg. 2019;11:725-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Senn on the Healing of Aseptic Bone Cavities by Implantation of Antiseptic Decalcified Bone. Ann Surg. 1889;10:352-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Urist MR. Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science. 1965;150:893-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4079] [Cited by in RCA: 3691] [Article Influence: 61.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Allport J, Ramaskandhan J, Siddique MS. Nonunion Rates in Hind- and Midfoot Arthrodesis in Current, Ex-, and Nonsmokers. Foot Ankle Int. 2021;42:582-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ajiboye RM, Hamamoto JT, Eckardt MA, Wang JC. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of concentrated bone marrow aspirate with allograft and demineralized bone matrix for posterolateral and interbody lumbar fusion in elderly patients. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:2567-2572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kendal AR, Khalid A, Ball T, Rogers M, Cooke P, Sharp R. Complications of minimally invasive calcaneal osteotomy versus open osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36:685-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Davis D, Seaman TJ, Newton EJ. Calcaneus Fractures. 2023 Jul 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Azam MT, Butler JJ, Duenes ML, McAllister TW, Walls RC, Gianakos AL, Kennedy JG. Advances in Cartilage Repair. Orthop Clin North Am. 2023;54:227-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Murawski CD, Kennedy JG. Operative treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1045-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Perry KI, Hanssen AD. Orthopaedic Infection: Prevention and Diagnosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25 Suppl 1:S4-S6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |