Published online Feb 18, 2023. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v14.i2.64

Peer-review started: September 1, 2022

First decision: December 19, 2022

Revised: December 22, 2022

Accepted: February 2, 2023

Article in press: February 2, 2023

Published online: February 18, 2023

Processing time: 169 Days and 11.4 Hours

Globally, complete neurological recovery of spinal cord injury (SCI) is still less than 1%, and 90% experience permanent disability. The key issue is that a phar

To investigate the regeneration mechanism of SCI and neuroprotective-neuroregenerative effects of HNSCs-secretome on subacute SCI post-laminectomy in rats.

An experimental study was conducted with 45 Rattus norvegicus, divided into 15 normal, 15 control (10 mL physiologic saline), and 15 treatment (30 μL HNSCs-secretome, intrathecal T10, three days post-traumatic). Locomotor function was evaluated weekly by blinded evaluators. Fifty-six days post-injury, specimens were collected, and spinal cord lesion, free radical oxidative stress (F2-Iso

HNSCs-secretome significantly improved locomotor recovery according to Basso, Beattie, Bresnahan (BBB) scores and increased neurogenesis (nestin, BDNF, and GDNF), neuroangiogenesis (VEGF), anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2), anti-inflammatory (IL-10 and TGF-β), but decreased pro-inflammatory (NF-κB, MMP9, TNF-α), F2-Isoprostanes, and spinal cord lesion size. The SCI regeneration mechanism is valid by analyzed outer model, inner model, and hypothesis testing in PLS SEM, started with pro-inflammation followed by anti-inflammation, anti-apoptotic, neuroangiogenesis, neurogenesis, and locomotor function.

HNSCs-secretome as a potential neuroprotective-neuroregenerative agent for the treatment of SCI and uncover the SCI regeneration mechanism.

Core Tip: The human neural stem cell secretomes is effective in spinal cord injury (SCI) treatment, based on locomotor function improvement, decreased size of spinal cord lesions, and biomarkers expression. Based on partial least squares structural equation modeling analysis, the regeneration mechanism of SCI started with pro-inflammation, anti-inflammation, anti-apoptotic, neuroangiogenesis, neurogenesis, finally, locomotor improvement.

- Citation: Semita IN, Utomo DN, Suroto H. Mechanism of spinal cord injury regeneration and the effect of human neural stem cells-secretome treatment in rat model. World J Orthop 2023; 14(2): 64-82

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v14/i2/64.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v14.i2.64

Spinal cord injury (SCI) can result in permanent neurologic deficits; complete SCI neurological recovery is still less than 1%, and 90% experience permanent disability[1]. Secondary damage is caused by oxidative stress, inflammation, ischemia, apoptosis, and glial scar formation[2]. It can result in axon regeneration failure, leading to neurological deterioration[2]. The SCI regeneration mechanism is still uncertain[3]. Pajer et al[4] stipulate that SCI pathophysiology can be divided into three overlapping stages: Acute, subacute, and chronic. The injury begins with trauma that results in microvascular damage in the form of bleeding, thrombosis, and vasospasm[5]. This microvascular damage causes the spinal cord to undergo hypoperfusion, hypoxia, and ischemia[6]. Ischemia in the spinal cord affects cellular and molecular inflammation processes, neuron and neuroglia cell apoptosis, and glial scar formation, which mechanically and chemically inhibit SCI regeneration[5,6].

SCI management is still controversial, as there is no global consensus guideline and no effective pharmacological neuroprotective-neuroregenerative agent[7,8]. Current SCI management is focused on treating the secondary injury[2]. The secretomes of stem cell help mitigate the risk of immune rejection, reduce the risk of tumorigenesis, and cryopreserve treatments while avoiding the issues of maintaining cell viability[9]. The secretomes of stem cell are more economical and readily available in emergency cases as they can be mass-produced[10].

The effect of human neural stem cells (HNSCs) secretome on SCI is still unclear. Consequently, this study aimed to investigate the SCI regeneration mechanism and HNSCs-secretome treatment effects on subacute SCI post-laminectomy by analyzing free radical oxidative stress (F2-Isoprostanes), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin-10 (IL-10), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), B cell lymphoma (Bcl)-2, nestin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), gleal cell line neurotrophic factor (GDNF), spinal cord lesion, and locomotor function. For this purpose, we used a well-established Rattus norvegicus model of SCI contusion-compression.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Faculty Dentistry, University of Jember (REC.1112/UN25.8/KEPK/DL/2021). All rats were approved by the animal health office (No.503/ A.1/0005. B/35.09.325/2020).

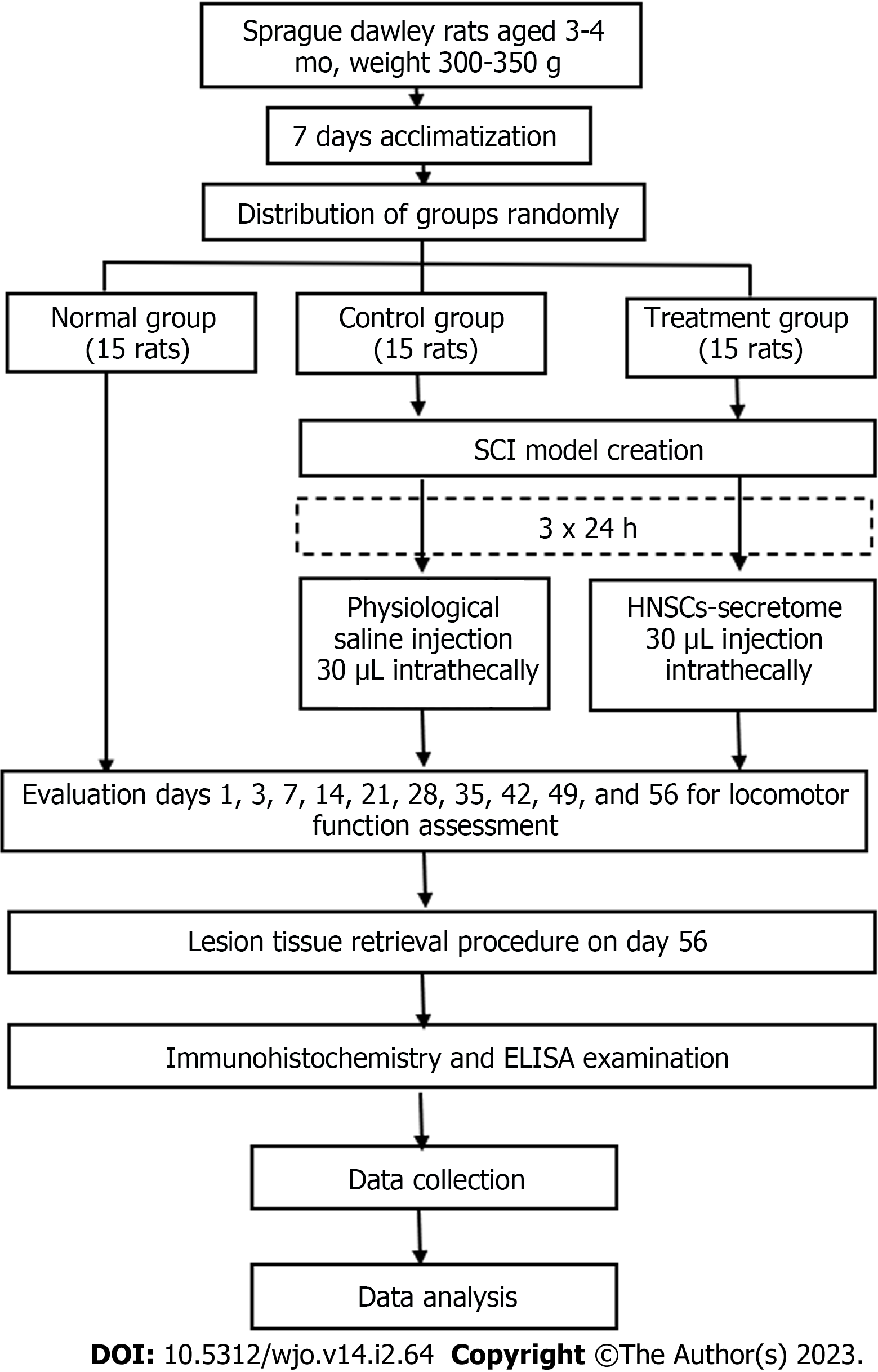

The research was a proper experimental study. The Lemeshow formula counted the sample size (n = 15 rats), with correction factors of 20%. The rats were randomly grouped into the following three groups: Normal (15 experimental rats did not have SCI and did not get HNSCs-secretome), control (15 experimental rats did have SCI with physiologic saline), and treatment (15 experimental rats did have SCI with HNSCs-secretome) (Figure 1). The treatment group received a 30 μL HNSCs-secretome intrathecal injection in T10 three days after the SCI and laminectomy. Treatment and control groups were replicated 15 times, and we observed the study over 56 d. The study’s independent variable was HNSCs-secretome treatment, whereas the dependent variables were GDNF, BDNF, nestin, Bcl-2, VEGF, TGF-β, IL-10, MMP9, F2-Isoprostanes, TNF-α, NF-κB, locomotor function, and spinal cord lesion size.

HNSCs-secretome is characterized by the presence of nerve cells as well as the nestin, BDNF, and growth associated protein-43. NSCs were derived from 2 × 5 × 106 adipose-mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) with fresh frozen nerve scaffolds under 5% hypoxic conditions. Secretom does not provide an immune compatibility effect, therefore in this study secretoms were used from humans, not from rats[3,11]. HNSCs-secretome 50 cc produced on June 21, 2021 at the Stem Cell Installation and Network Bank of RS Dr. Soetomo No. 301/VAL/FORM/BJRS/10/2021, with ethical clearance No. 0059/KEPK/ IX/2020.

The adult male Rattus norvegicus pure strain Sprague Dawley rats were three to four months old and weighed 300-350 g. Inclusion criteria were male, age 3-4 mo, weight 300-350 g, pure line, and healthy with a healthy statement from a veterinary polyclinic. The exclusion criteria were experimental rats that had received immunomodulatory therapy and were fatally ill. Acclimatization was carried out for seven days by one laboratory assistant and two veterinarians. The rats were kept in separate cages, consisting of a plastic box with woven wire as a cover, with each cage (45 cm × 30 cm × 15 cm) containing one rat. The floor mat was covered with wood shavings and a pad underneath to absorb urine and retain moisture. Air conditioning provided comfort and maintained a room temperature of 20-24 ˚C and humidity of 50%-70%. An exhaust fan was used to remove the ammonia smell, and the environment was a quiet room with 12-h light and dark cycles. The light sources were 300 Lux electric lamps positioned 1 m from the floor. The cage was cleaned every three days with soap and running water. Feed comprised 30-35 g of pellets (10% of bodyweight) and 30-35 mL of mineral water (10% of bodyweight).

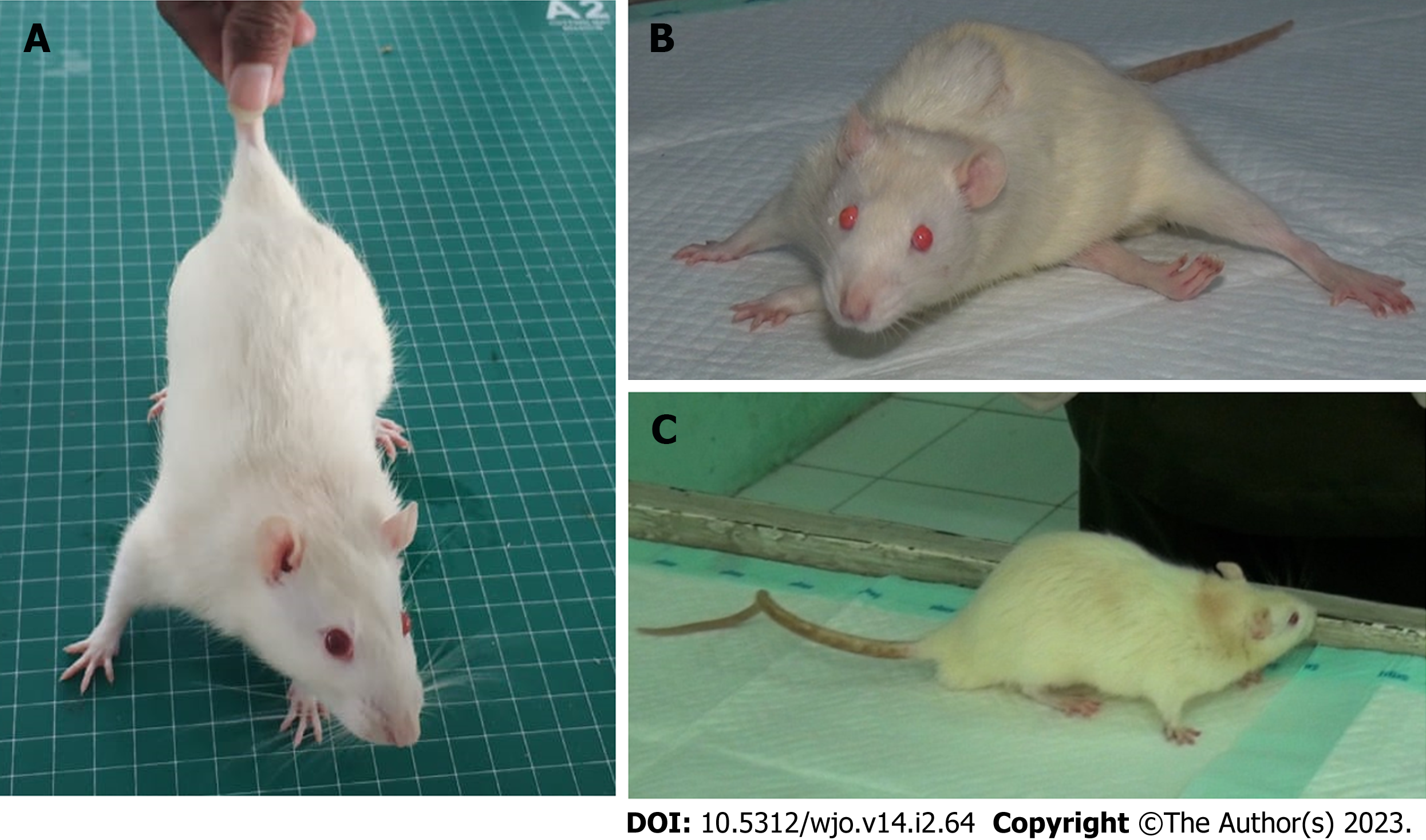

Contusion-compression of the spinal cord was performed with the commercially available spinal cord impactor aneurysm Yasargil clip, with a length of 7 mm and a 65 g load (equivalent to 150 k Dyne). The rats were anesthetized using ketamine (75 mg/kg) and acepromazine 3 mg/kg intraperitoneal. The rats were placed on a fixation board in a prone position, and the back fur was shaved to approximately 2 mm. The operating area was disinfected with 10% betadine and 75% alcohol. The surgical level was marked by tracing the level of the T12 rib to the T12 spinous process using a 2 cm skin incision. A T10-T11 partial laminectomy was conducted to expose the spinal cord. The tip of the titanium aneurysm Yasargil clip was placed at a 1-mm distance from the anterior and posterior of the spinal cord, and the spinal cord was impacted suddenly for 60 s by retracting the tip using an applicator. This retraction induced an SCI contusion-compression model with the dura appearing flat and cloudy white. The operating field was cleaned using saline, and the muscle and skin were sutured together in layers.

Three days post-injury, the treatment and control group rats were completely paraplegic. The control group was administered an intrathecal injection of 10 mL physiologic saline. The treatment group was administered an intrathecal injection of 30 μL HNSCs-secretome under general anesthesia, which was centered at the injury site and 1.5-2 mm deep from the dura to the subarachnoid space, with a tilt angle of 30°–40° using a 50 μL Hamilton Syringe. The rats received normal saline, tolfenamic acid 4 mg/kg, and enrofloxacin 10 mg/kg subcutane, were placed under a 5 W heating lamp. Manual bladder drainage was conducted twice daily until micturition was normal.

The Basso, Beattie, Bresnahan (BBB) open-field test was performed on days one, three, seven, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, and 56 after injury to assess locomotor expression. The BBB measures the tail, body, legs, trunk stability, limb movement, and toe clearance, all of which are examined to measure locomotor abilities. The score shows a range of numbers between 0 and 21. A score of 0 indicates no movement, whereas a score of 21 represents normal movement without a locomotor disorder. The data collector and outcome adjudicator/data analyst were blinded.

The rats' termination was carried out on day 56 through the induction of inhalation anesthetics. The 5-cm SCI was separated from the vertebral column and marked at the cranial end. The SCI materials were put in a pot and fixed in a 10% formalin buffer. All SCI specimens were sent to the Anatomy and Pathophysiology Laboratory for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and immunohistochemistry examination, tabulation of results, and analysis were conducted according to the blinding principle. The data collector and outcome adjudicator/data analyst were blinded.

With hematoxylin and eosin staining, measurements of the spinal cord lesions were carried out in both the control and treatment groups, then analyzed with Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software (Version 25, IBM) was used to analyze the differences between groups by non-parametric test, followed by Mann Whitney test. A P-value of more than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

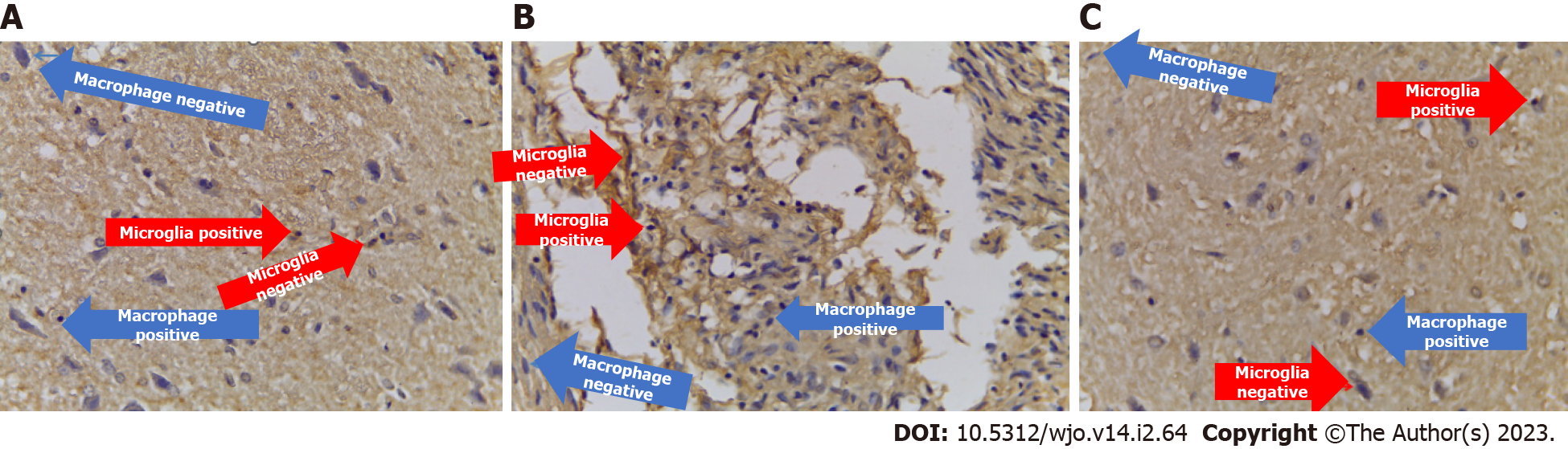

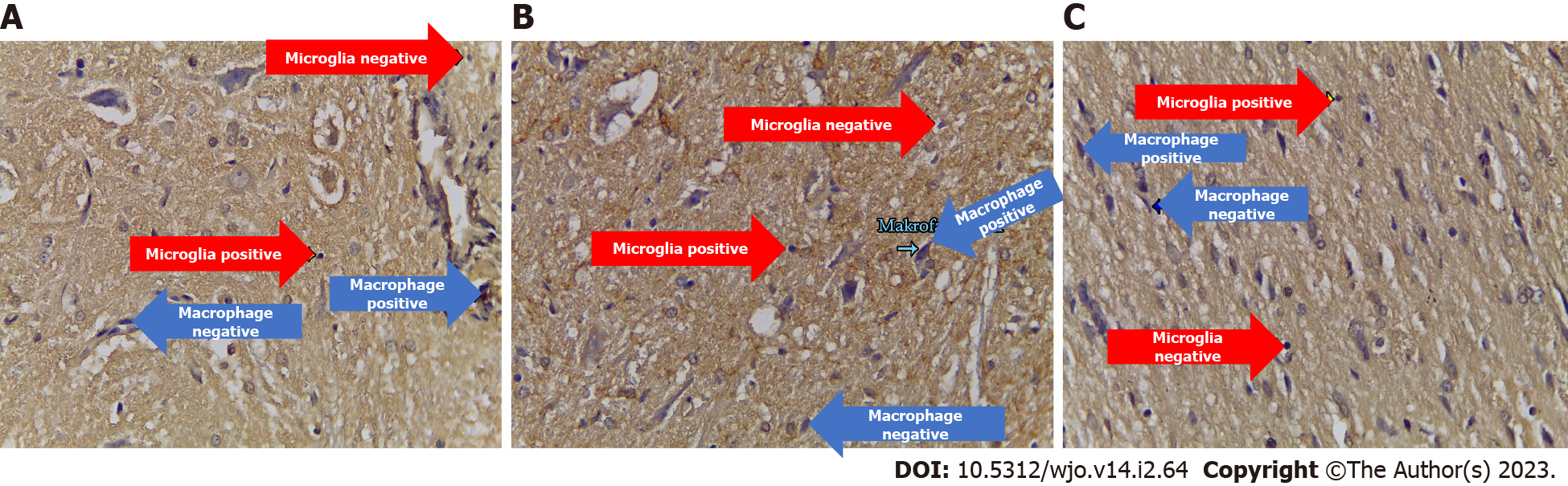

GDNF, BDNF, nestin, Bcl-2, VEGF, TGF-β, IL-10, MMP9, and NF-κB were evaluated using indirect immunohistochemical quantitative measurements. The data collector and outcome adjudicator/data analyst were blinded. Fifteen specimens of spinal cord tissue taken from animals in each group. In each group, we observed an average value of 10 fields of view, and every field of view had 625 μ2 with 400 × magnification.

Immunohistochemical operational procedures were as follows: The specimens were immersed in the xylol solution for 3-5 min, then in absolute ethanol for 1-3 min, and finally in 70% ethanol for 1-3 min. They were then washed 3 times with Aquabidest, and the edge of the slide was cleaned with a tissue. They were then dropped with H2O2 3%, incubated at room temperature for 10 min, washed 3 times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the edge of the slide was again cleaned with a tissue. They were then dropped with Trypsin 0.025%, and incubated at 37 °C for 6 min, washed 3 times in PBS, and the edge of the slide again cleaned with a tissue. Specimens were then dropped with Ultra V Block and incubated at room temperature for 5 min, with the edge of the slide cleaned again (no need to wash). They were then dropped with monoclonal antibody which has been diluted (1:100) and incubated at room temperature for 25-30 min, washed with PBS 3 times, and the edge of the slide cleaned with a tissue. Drops of biotin, incubation at room temperature for 10 min, washed with PBS 3 times, and the edge of the slide cleaned with a tissue. Specimens were then dropped with horseradish peroxidase polymer (streptavidin peroxidase conjugate), incubated at room temperature for 10 min, washed with PBS 3 times, and the edge of the slide cleaned with a tissue. They were then dropped with diaminobenzidine chromogen (20 mL/1 mL substrate), incubated at room temperature for 5-15 min in a dark room, washed Aquabidest 3 times, cleaned, painted with Meyer Hematoxylin at room temperature, then incubated for 6-15 min, washed in running water 3 times, and finally soaked in water for 10 min, drained, mounting, and microscopic readings were taken.

The specimen for ELISA was collected from cardiac blood. The TNF-α analysis used serum, and F2-Isoprostanes used plasma for the analysis. The ELISA kit for the TNF-α analysis used the Sandwich-ELISA principle, while the ELISA kit for the F2-Isoprostanes analysis used the Competitive-ELISA principle. TNF-α and F2-Isoprostanes were evaluated using quantitative measurements.

The data in this research is reported as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean. SPSS software (Version 25, IBM) was used to analyze the differences between groups by ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. A P-value of more than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS SEM) was used to analyze the pathway mechanism of SCI regeneration through analysis of the outer model, inner model, and hypothesis testing. The outer model measurement of PLS SEM is based on convergent validity, discriminant validity, and composite reliability. Convergent validity can be determined from the value of the loading factor and average variance extracted (AVE). If the loading factor value is more than 0.7, the correlation between indicator and variable is valid. If the AVE value more than 0.5, the ability of the variable value to represent the original data score is valid. Discriminant validity testing the construct indicator has a higher cross-loading value than other construct indicators, whereas composite reliability is used to measure the consistency of variables. If the composite reliability value is more than 0.7, it is declared valid.

Path bootstrapping analysis is a description of the inner model and the results of the path analysis hypothesis test, based on the original sample value and the statistical T value. If the statistical T value is greater than 1.9 (T table value) or the P value is less than 0.05, the direct effect of the latent va

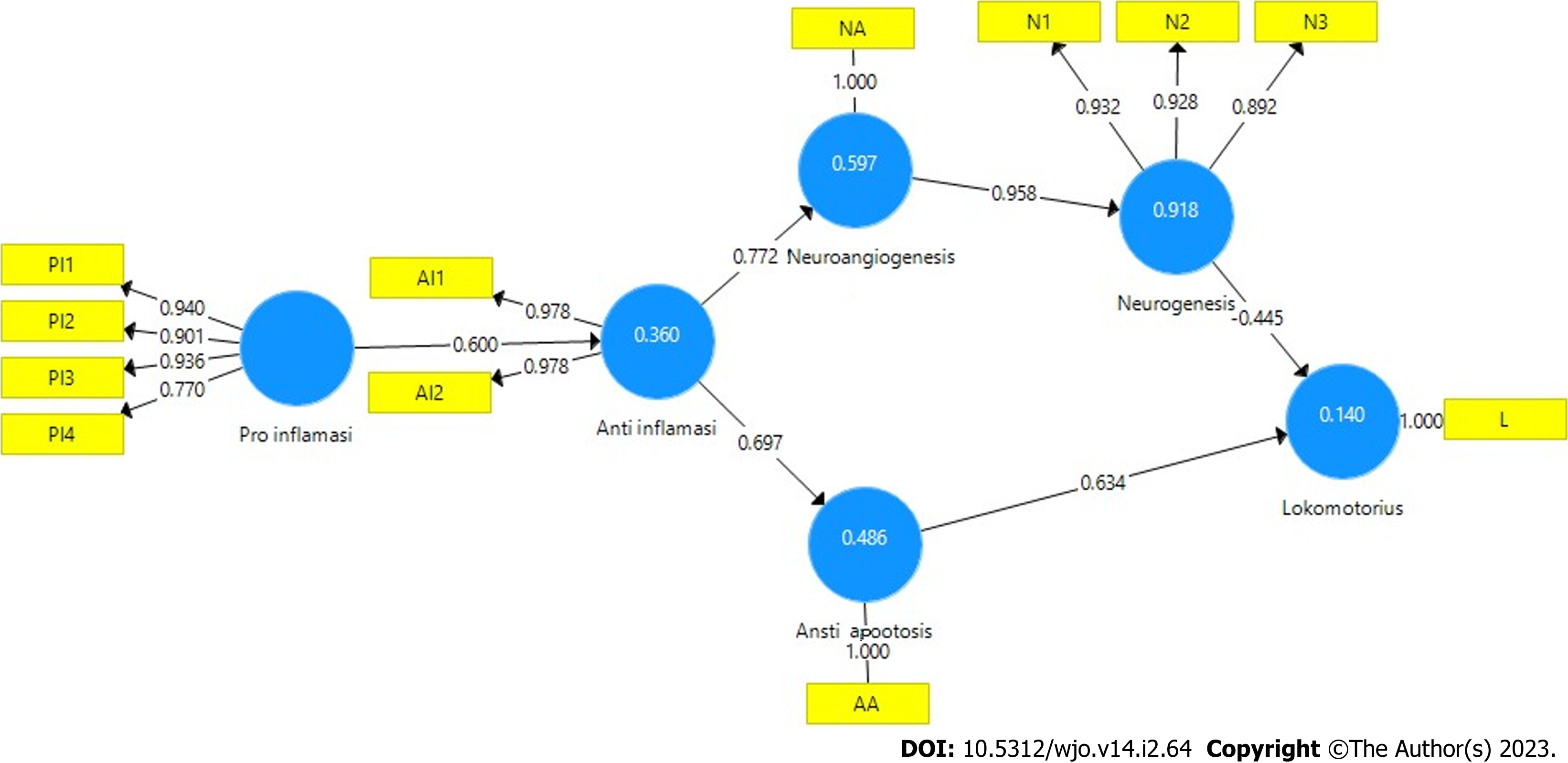

The SCI regeneration mechanism was analyzed using PLS SEM. The test results of the measurement model (outer model) are valid, based on the PLS algorithm (Figure 2), the analysis of convergent validity is more than 0.7 (Table 1), the AVE value is more than 0.5 (Table 2), the Cronbach’s Alpha value is more than 0.5 (Table 2), composite reliability is more than 0.7 (Table 2), and discriminant validity is good (Table 3).

| Anti apoptotic | Anti inflammatory | Lokomotorius | Neuroangiogenesis | Neurogenesis | Pro inflammatory | |

| Anti apoptotic | 1.000 | |||||

| Anti inflammatory 1 | 0.978 | |||||

| Anti inflammatory 2 | 0.978 | |||||

| Lokomotorius | 1.000 | |||||

| Neurogenesis 1 | 0.932 | |||||

| Neurogenesis 2 | 0.928 | |||||

| Neurogenesis 3 | 0.892 | |||||

| Neuroangiogenesi | 1.000 | |||||

| Pro inflammatory 1 | 0.940 | |||||

| Pro inflammatory 2 | 0.901 | |||||

| Pro inflammatory 3 | 0.936 | |||||

| Pro inflammatory 4 | 0.770 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | rho_A | Composite reliability | Average variance extracted | |

| Anti apoptotic | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Anti inflammatory | 0.954 | 0.954 | 0.978 | 0.956 |

| Lokomotorius | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Neuroangiogenesis | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Neurogenesis | 0.907 | 0.915 | 0.941 | 0.842 |

| Pro inflammatory | 0.917 | 0.979 | 0.938 | 0.792 |

| Anti apoptotic | Anti inflammatory | Lokomotorius | Neuroangiogenesis | Neurogenesis | Pro inflammatory | |

| Anti apoptotic | 1.000 | 0.697 | 0.271 | 0.850 | 0.815 | 0.085 |

| Anti inflammatory 1 | 0.663 | 0.978 | -0.293 | 0.714 | 0.704 | 0.642 |

| Anti inflammatory 2 | 0.699 | 0.978 | -0.140 | 0.796 | 0.739 | 0.532 |

| Lokomotorius | 0.271 | -0.220 | 1.000 | 0.064 | 0.072 | -0.869 |

| Neurogenesis 1 | 0.725 | 0.691 | -0.037 | 0.961 | 0.932 | 0.369 |

| Neurogenesis 2 | 0.776 | 0.612 | 0.313 | 0.862 | 0.928 | -0.006 |

| Neurogenesis 3 | 0.748 | 0.736 | -0.084 | 0.804 | 0.892 | 0.338 |

| Neuroangiogenesi | 0.850 | 0.772 | 0.064 | 1.000 | 0.958 | 0.319 |

| Pro inflammatory 1 | 0.078 | 0.580 | -0.865 | 0.268 | 0.201 | 0.940 |

| Pro inflammatory 2 | -0.073 | 0.496 | -0.760 | 0.192 | 0.118 | 0.901 |

| Pro inflammatory 3 | 0.257 | 0.654 | -0.740 | 0.455 | 0.392 | 0.936 |

| Pro inflammatory 4 | -0.206 | 0.153 | -0.881 | 0.012 | 0.046 | 0.770 |

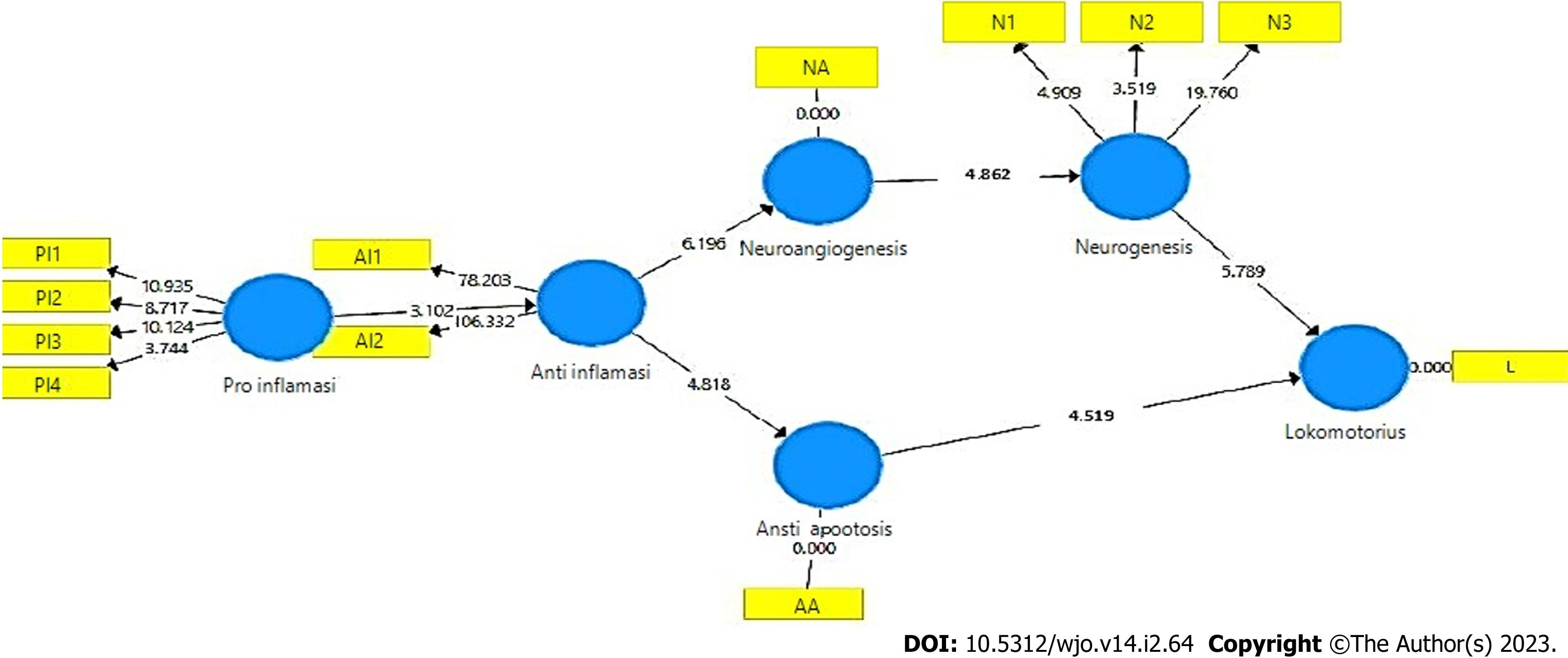

The results of the analysis of the inner model (structural model) using bootstrapping and blindfolding PLS SEM procedures are valid and show the path coefficients that are in accordance with the hypothesized theory, significant with T-statistics greater than 1.9 (T-table) and P value less than 0.05 (Figure 3, Table 4). The relationship between latent variables in the inner model was analyzed, with F square (effect size) more than 0.05 (Table 5), Q square (prediction relevance) more than 0 (Table 6), and path coefficients positive. For R square (coefficient of determination on endogenous variables), the anti-inflammatory value of 0.860 indicates an effect of 86%, the anti-apoptotic value of 0.680 indicates an effect of 68%, neuroangiogenesis of 0.776 indicates an effect of 77%, neurogenesis of 0.444 indicates an influence of 44%, and locomotory of 0.536 indicates an influence of 53% (Table 7).

| O | M | STDEV | T statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P values | |

| Anti apoptotic - > lokomotorius | 0.109 | 0.129 | 0.210 | 4.519 | 0.000 |

| Anti inflammatory - > anti apoptotic | 0.697 | 0.692 | 0.145 | 4.818 | 0.000 |

| Anti inflammatory- > neuroangiogenesis | 0.772 | 0.768 | 0.125 | 6.196 | 0.000 |

| Neuroangiogenesis - > neurogenesis | 0.176 | 0.183 | 0.258 | 4.682 | 0.000 |

| Neurogenesis - > lokomotorius | 0.754 | 0.782 | 0.130 | 5.789 | 0.000 |

| Pro inflammatory - > anti inflammatory | 0.600 | 0.622 | 0.193 | 3.102 | 0.002 |

| Anti apoptotic | Antiinflammatory | Lokomotorius | Neuroangiogenesis | Neurogenesis | Pro inflammatory | |

| Anti apoptotic | 0.197 | |||||

| Anti inflammatory | 2.126 | 3.458 | ||||

| Lokomotorius | ||||||

| Neuroangiogenesis | 0.797 | |||||

| Neurogenesis | 0.563 | |||||

| Pro inflammatory | 6.163 |

| SSO | SSE | Q² (= 1-SSE/SSO) | |

| Anti apoptotic | 15.000 | 8.131 | 0.458 |

| Anti inflammatory | 30.000 | 24.178 | 0.194 |

| Lokomotorius | 15.000 | 6.222 | 0.585 |

| Neuroangiogenesis | 15.000 | 13.410 | 0.106 |

| Neurogenesis | 45.000 | 44.724 | 0.006 |

| Pro inflammatory | 60.000 | 60.000 |

| R square | R square adjusted | |

| Anti apoptotic | 0.680 | 0.655 |

| Anti inflammatory | 0.860 | 0.850 |

| Lokomotorius | 0.536 | 0.459 |

| Neuroangiogenesis | 0.776 | 0.758 |

| Neurogenesis | 0.444 | 0.401 |

The rats were examined for eight weeks to assess the recovery of their motor function. Locomotor recovery recorded on day seven and continued until day 56. The treatment group’s mean BBB score was 19.93, whereas the control group’s score was 10.33. The mean difference in the BBB scores was 9.6 (BBB score 0-21). Based on the Tukey HSD test, control and treatment groups were different, with a significance value of P = 0.001 (P < 0.05). The treatment group demonstrated a higher effect on improving the value of locomotor recovery in the rat SCI subacute contusion-compression model (Figure 4).

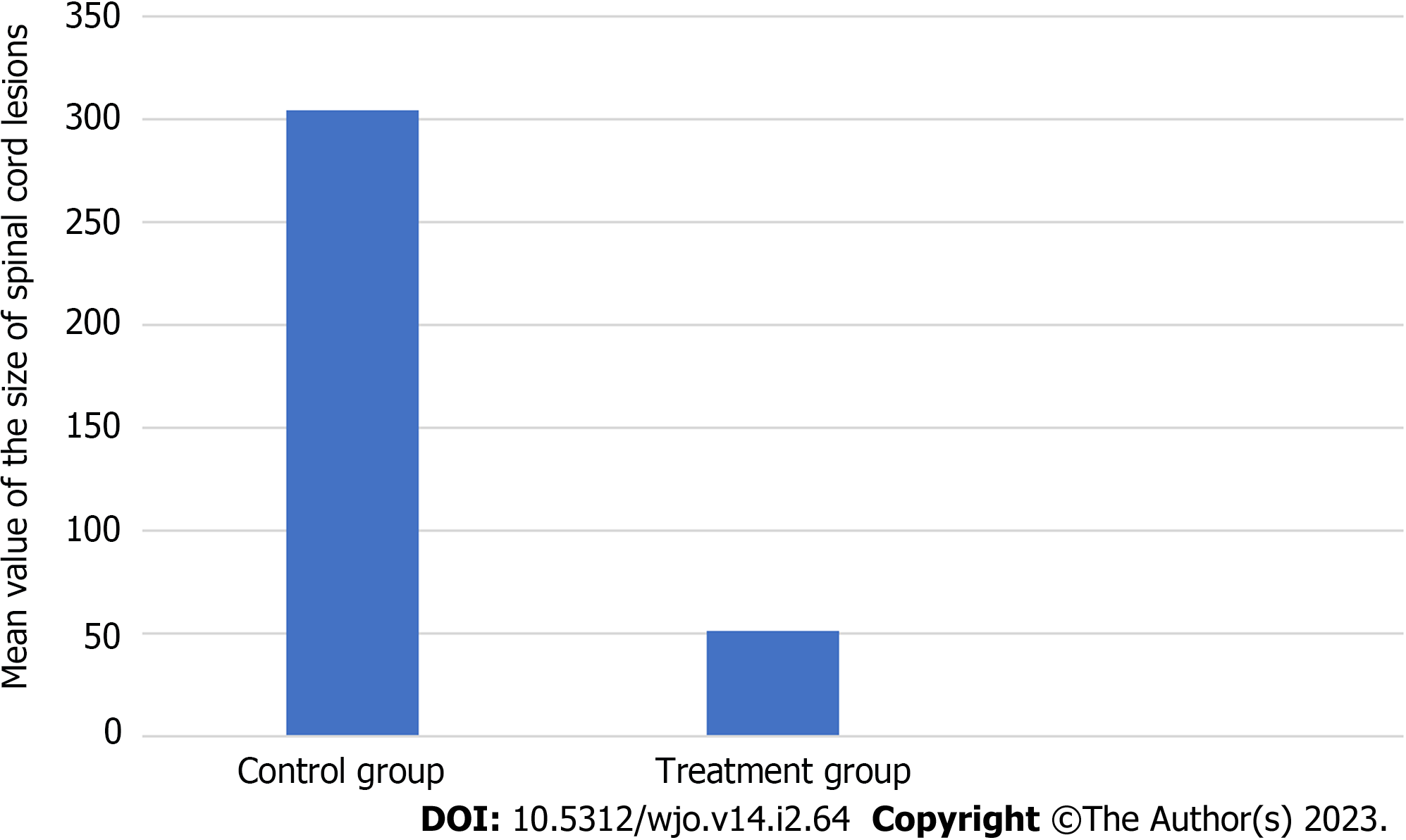

The results of measurements size of spinal cord lesions in the control and treatment groups, successive mean values of 304.019 and 51.676, with the non-parametric test (Mann Whitney) found a significant difference in the size of the spinal cord lesion with a P = 0.000 (Figure 5).

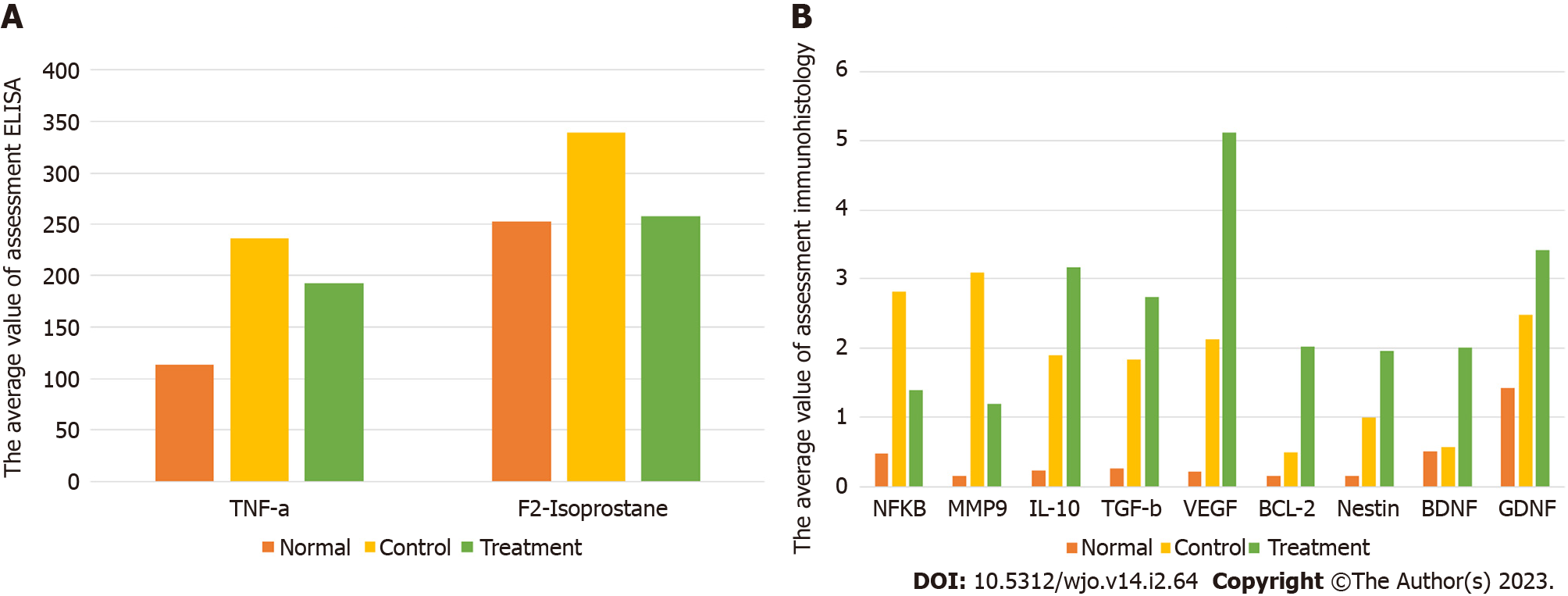

The examination results of oxidative stress (F2-Isoprostanes) showed a significant decrease in the treatment group compared to the control group, with significance values of P = 0.001. The level of F2-Isoprostanes in the treatment group 258.40, were smaller than the control groups 338.82 (Figure 6A, Table 8).

| Biomarker | Group | Group | P value | |

| Oxidative stress | F2-Isoprostanes | Treatment (mean = 258.40; SD = 12.45) | Normal (mean = 252.59; SD = 25.54) | 0.938 |

| Control (mean = 338.82; SD = 36.87) | 0.001 | |||

| Pro-inflammatory | NF-kB | Treatment (mean = 1.400; SD = 0.254) | Normal (mean = 0.475; SD = 0.206) | 0.003 |

| Control (mean = 2.820; SD = 0.531) | 0.000 | |||

| MMP-9 | Treatment (mean = 1.19; SD = 0.931) | Normal (mean = 0.160; SD = 0.213) | 0.217 | |

| Control (mean = 3.09; SD = 1.056) | 0.001 | |||

| TNF-α | Treatment (mean = 171.85; SD = 35.84) | Normal (mean = 105.07; SD = 11.34) | 0.002 | |

| Control (mean = 215.14; SD = 15.38) | 0.032 | |||

| Anti-inflammatory | IL-10 | Treatment (mean = 3.160; SD = 0.801) | Normal (mean = 0.240; SD = 0.167) | 0.000 |

| Control (mean = 1.900; SD = 0.734) | 0.022 | |||

| TGF-β | Treatment (mean = 2.740; SD = 0.684) | Normal (mean = 0.260; SD = 0.181) | 0.000 | |

| Control (mean = 1.840; SD = 0.572) | 0.047 | |||

| Neuroangiogenesis | VEGF | Treatment (mean = 5.12; SD = 0.878) | Normal (mean = 0.220; SD = 0.130) | 0.000 |

| Control (mean = 2.120; SD = 0.889) | 0.000 | |||

| Anti-apoptotic | Bcl-2 | Treatment (mean = 2.02; SD = 0.712) | Normal (mean = 0.160; SD = 0.151) | 0.000 |

| Control (mean = 0.500; SD = 0.380) | 0.001 | |||

| Neurogenesis | Nestin | Treatment (mean = 1.96; SD = 0.610) | Normal (mean = 0.160; SD = 0.114) | 0.000 |

| Control (mean = 1.000; SD = 0.524) | 0.018 | |||

| BDNF | Treatment (mean = 2.01; SD = 0.576) | Normal (mean = 0.40; SD = 0.482) | 0.000 | |

| Control (mean = 0.57; SD = 0.468) | 0.001 | |||

| GDNF | Treatment (mean = 3.420; SD = 2.480) | Normal (mean = 1.420; SD = 0.356) | 0.000 | |

| Control (mean = 2.480; SD = 0.788) | 0.043 |

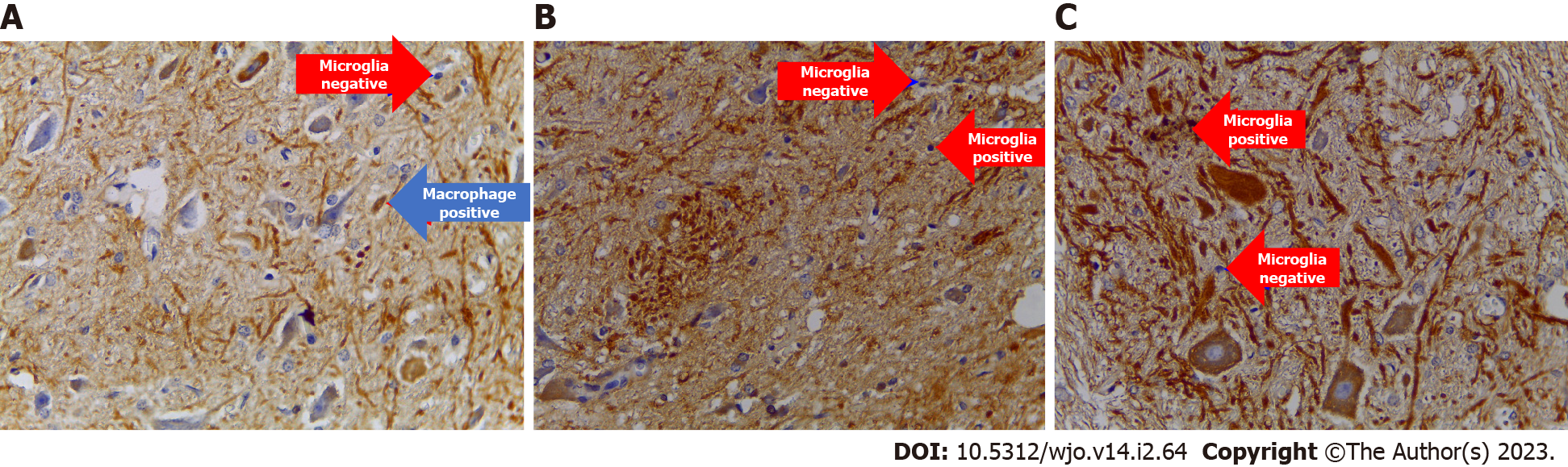

The examination results of neuro pro-inflammation biomarkers (NF-κB, TNF-α, and MMP9) showed a significant decrease in the treatment group compared to the control group, with successive significance values of P = 0.000, P = 0.032, and P = 0.001. The number of cells expressing NF-κB, TNF-α, and MMP9 in the treatment group, with successive mean values of 1.400, 171.85, and 1.19, were smaller than the control groups, with values of 2820, 215.1, and 3.09 (Figures 6A, 6B and Figure 7, Table 8).

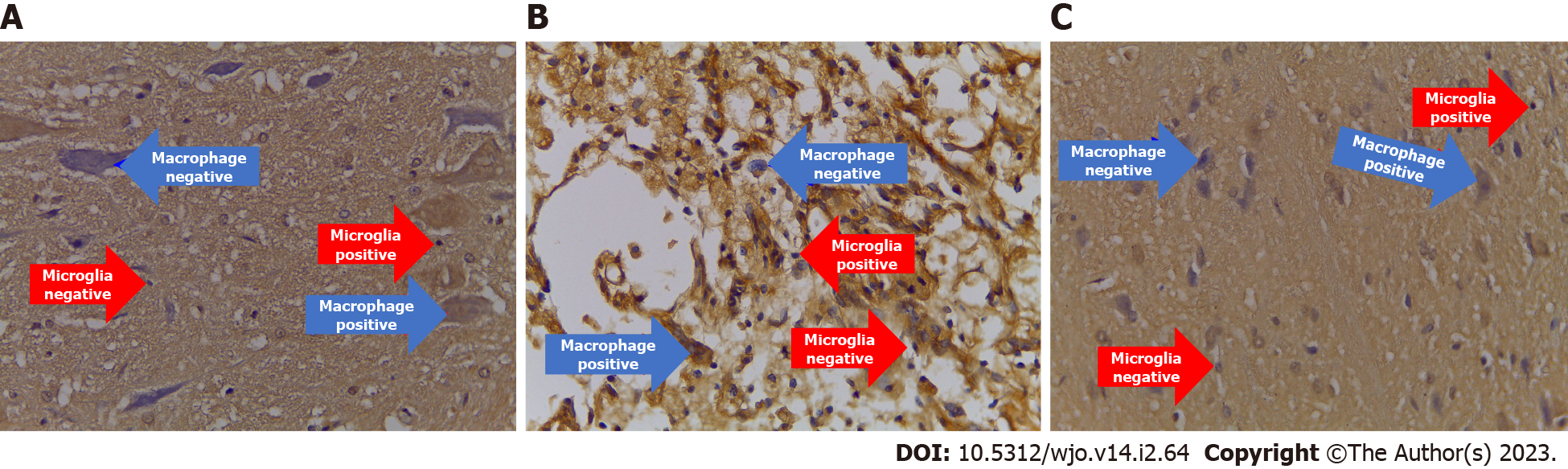

The immunohistochemical examination of neuro anti-inflammation biomarkers (IL-10 and TGF-β) showed a significant increase in the treatment group compared to the control group, with successive significance values of P = 0.022 and P = 0.047. The number of cells expressing IL-10 and TGF-β in the treatment group, with successive mean values of 3.160 and 2.740, were greater than the control groups, with values of 1.900 and 1.840 (Figures 6B and Figure 8, Table 8).

Neuroangiogenesis cytokine (VEGF): The number expressing VEGF in the treatment group significantly differed from the control group (P = 0.000). Moreover, the number of cells expressing VEGF in the treatment group (5.12) was greater than the control group (2.120) (Figures 6B and Figure 9, Table 8).

Anti-apoptotic cytokine (Bcl-2): The number expressing Bcl-2 in the treatment group significantly differed from the control group (P = 0.001). Moreover, the number of cells expressing Bcl-2 in the treatment group (2.02) was greater than the control group (0.500) (Figures 6B and 10, Table 8).

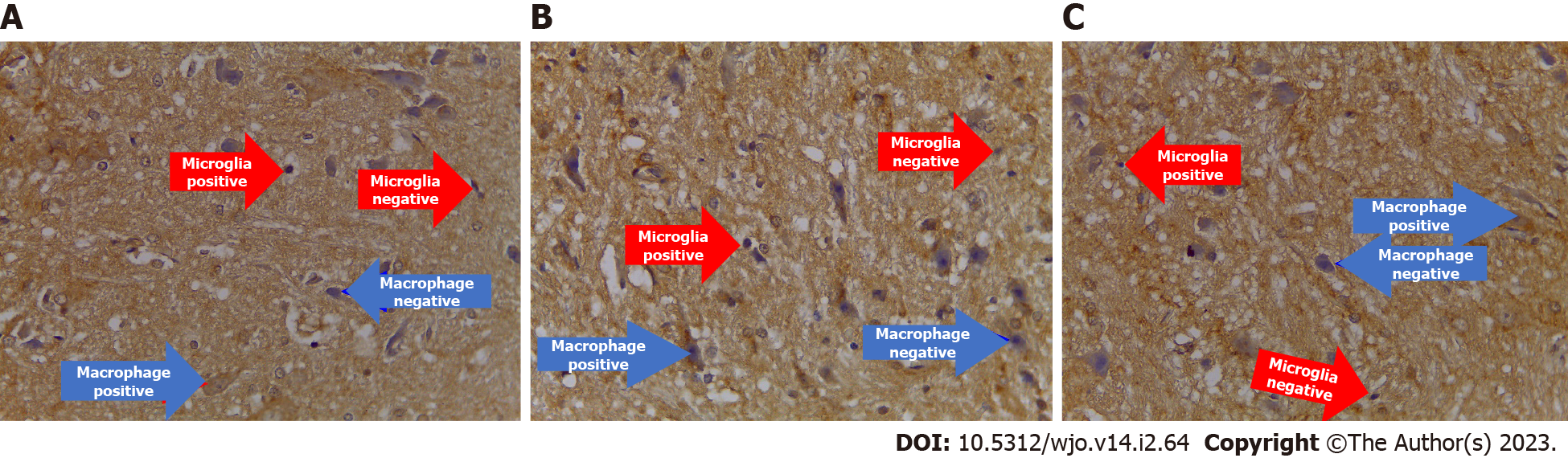

Neurogenesis cytokine (nestin, BDNF, GDNF): The results of the immunohistochemical examination of neurogenesis biomarkers (nestin, BDNF, and GDNF) showed a significant increase in the treatment group compared to the control group, with successive significance values of P = 0.018, P = 0.001, and P = 0.043. The number of cells expressing nestin, BDNF, and GDNF in the treatment group with successive mean values of 1.96, 2.01, and 3.420 were greater than the control groups, which had mean values of 1.00, 0.57, and 2.480 (Figures 6B and 11, Table 8).

After HNSCs-secretome intrathecal injections in model SCI post-laminectomy rats, the results showed that HNSCs-secretome increased locomotor function, decreased size of spinal cord lesion, increased GDNF, BDNF, nestin, VEGF, Bcl-2, TGF-β, IL-10, and decreased TNF-α, F2-Isoprostanes, MMP-9, NF-κB. The mechanism of SCI was valid, based on the analyzed outer model, inner model, and hypothesis testing. It began with pro-inflammation, anti-inflammation, anti-apoptotic, neuroangiogenesis, neurogenesis, and locomotor function.

The results of this study are in accordance with findings from Cunningham et al[3] who stated that MSC-secretome in brain ischemia could modulate neurogenesis with an increase in BDNF, GDNF, and NT3. Kim et al[12] stated that adipose derived stem cell-secretome can provide anti-free-radical effects and reduce oxidative stress with the expression of F2-Isoprostane. Honmou et al[13] also stated that mononuclear stem cell secretome in SCI inhibited microvascular obstruction and thrombosis, promoted vasodilation, immunomodulation, and neuroprotection, while Santos et al[14] and Yang et al[15] stated that NSC-secretome in SCI stimulated the transformation of phenotype M1 to phenotype M2 of macrophages, microglia, and astrocytes through PgE2, IL-10, TGF-β, proliferator-activated receptor gamma[14,15]. Macrophage M2 secreted anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-10, TGF-β, and hepatocyte growth factor, whereas macrophage M1 secreted pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MMP9, and F2-Isophostane[14,15]. Miranpuri et al[5] stated that after trauma, there was an increase in inflammatory cells, such as macrophages, neutrophils, dendrites, and T-cells, as a result of ruptured blood vessels and increased vascular permeability.

The results of the HNSCs-secretome in SCI study, there was a decrease in the oxidative stress cytokine F2-Isoprostane, accordance with previous research by Kim et al[12] who stated that NSC-secretome acts as an anti-free radical and anti-oxidative stress agent in mouse-model SCI. Santos et al[14] stated that NSC-secretome has an antioxidant role that reduces F2-Isoprostane by inhibiting endoperoxidase, arachidonic acid, and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Oxidative stress plays an important role in the secondary phase of SCI[16]. The high oxidative stress of F2-Isoprostan affects the production of pro-apoptotic proteins, inhibits the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, damage to the function of the mitochondria, and affects DNA fragmentation, resulting in apoptotic[17]. The decrease in antioxidants also through neurotrophic NSC factors such as BDNF by increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes super oxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, sulfiredoxin, and sestrin2[18]. Antioxidant activity reduces ROS, increases mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2, and restores the mitochondrial electron-coupling capacity to its original state by inducing the accumulation of phosphorylated cAMP response element binding protein in the mitochondrial matrix and membrane, assisting the synthesis of complex V mitochondria to protect apoptotic[13].

After administering HNSCs-secretome to SCI-affected rats, there was a decrease in the pro-inflammatory cytokines NF-κB, MMP9, and TNF-α. Cheng et al[19] stated that NSC-secretome in SCI can suppress the inflammatory process by reducing the number of macrophages and microglia, decreasing inducible nitric oxide synthase by promoting SCI regeneration. Rong et al[20] stated that a decrease in proinflammatory cytokines occurred due to the autophagy activity of macrophages after administration of NSC-secretome. TNF-α, MMP9, and F2-Isoprostan decreased due to the transformation of mac

The decrease in NF-κB levels in this study is in accordance with research conducted by Wang et al[21] and Chen et al[22], which stated that there was a decrease in NF-κB levels after MSC-secretome intervention in mouse-model SCI. Chen et al[22] stated that a decrease in NF-κB will encourage axon regeneration through the phosphatase and tensin homolog/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway, where NF-κB serves to provide intracellular signals for macrophages to release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as MMP9 and TNF-α.

In this study, after administering HNSCs-secretome to SCI-affected rats, there was a decrease in the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, accordance with five previous studies by Huang et al[23], Cizkova et al[24], Huang et al[25], and Borhani-Haghighi et al[26], who stated that there was a decrease in TNF-α after MSC-secretome intervention in mouse-model SCI. The cytokine TNF-α is the most influential proinflammatory mediator in SCI, followed by other proinflammatory mediators such as interferon gamma, IL-6, and IL-8[27]. M1 phenotype macrophages secrete TNF-α through several mechanisms, namely NF-κB signaling, mitogen activated protein kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, extrinsic apoptotic pathway, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2[28]. TNF-α influences the development of secondary injury by increasing inflammation, oxidative stress (F2-Isoprostane), and modulating apoptotic mechanisms[20]. TNF-α plays a role in increasing the endogenous migration of NSCs to the site of SCI by upregulating the chemokine receptors (CCR)2, CCR3, and CCR4 and motif C-C receptors[29].

This study showed that HNSCs-secretome in SCI could reduce MMP9 biomarkers, accordance with the research of Xin et al[30], who stated that there was a decrease in MMP9 and an increase in tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) after administration of human bone marrow MSC (hBMSC) secretome in mouse-model SCI. MMP9 is inhibited by TIMP, while TIMP is inhibited by TGF-β[5]. This system modulates macrophage invasion and myelin destruction, which has an important role in neuropathic pain and contributes to glail scar formation[5].

In this study, after administering HNSCs-secretome to SCI-affected rats, in addition to decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, there was also an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β. The increase in IL-10 cytokines accordance with a study conducted by Chudickova et al[31], who stated that there was an increase in IL-10 as an anti-inflammatory factor in the systemic immunological response after BMSC secretome intervention on SCI. IL-10 can decrease MMP9 synthesis, induce macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 phenotypes, reduce inflammatory response, and suppress inflammatory cells[32,33]. IL-10 can inhibit the initial effect of MMP9 in terms of the degradation of the basal lamina blood medulla spinal barrier matrix[5,32]. Previous studies have shown that systemic IL-10 injection results in significant neuroprotection and greater functional improvement after SCI trauma[33]. IL-10 also provides anti-apoptotic support to neurons, reduction of lesion size, and improvement of locomotor function[33,34].

In this study, TGF-β increased in the treatment group compared to the control and normal groups, accordance with research by Cunningham et al[3], who state that there was an increase in TGF-β after MSC-secretome intervention in the ischemic brain. In addition to TGF-β, other anti-inflammatory agents, including BDNF, CXCL12, GDNF, hypoxia-inducible factor -1alpha (HIF-1α), IL-10, and VEGF, were also found. TGF-β also plays a role in overcoming matrix degradation, which is caused by the effect of MMP9[5]. TGF-β is involved in neuronal repair and regeneration and has been observed to inhibit neuronal damage and stimulate cell survival, growth, proliferation, differentiation, and invasion of neurons and glial cells[33].

Neuroangiogenesis cytokine (VEGF): The results of the HNSCs-secretome study in SCI showed an increase in the neuroangiogenesis cytokine VEGF, accordance with three previous studies by Cizkova et al[24], Liu et al[35], and Zhong et al[36], who stated that there was an increase in VEGF after MSC-secretome administration in mouse-model SCI. Cunningham et al[3] stated that in addition to VEGF, there was also an increase in other angiogenesis factors such as PDGF, BDNF, GDNF, basic fibroblast growth factor, CXCL12, Ang-1, Ang-2, and HIF-1α. Zhong et al[36] stated that administration of NSC-secretome in acute SCI can increase the expression of VEGF-A, which promotes axon proliferation and the migration of spinal cord microvascular endothelial cells from the third day post-injection, reduces lesion size, glial scars, and improves locomotor function in a mouse-model of SCI. VEGF is the highest protein found in the angiogenesis process, while VEGF-A is more commonly found in NSC-secretomes than in NSCs themselves[36]. VEGF plays a role in neuroprotection, with blood vessel formation starting on day 3 to 10 and optimally on day 14, where perfusion, oxygenation, and carbohydrate metabolism occur[24,35-37].

Anti-apoptotic cytokine (Bcl-2): In this study, there was an increase in Bcl-2 as an anti-apoptotic factor of HNSCs-secretome in a mouse model of SCI, consistent with three previous studies by Huang et al[23], Liu et al[35], and Zhou et al[27], who stated that there was an increase in Bcl-2 levels after MSC-secretome intervention in mouse-model SCI. Rong et al[20] stated that there was an increase in Bcl-2 and a decrease in caspase 3 due to the role of secretome anti-apoptotic factors in SCI regeneration. Bcl-2 functions as an anti-apoptotic factor by blocking the release of cytochrome-c from the mitochondria into the cytosol, thereby preventing the activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9[27,38,39].

Neurogenesis growth Factor (nestin, BDNF, and GDNF): The results of the HNSCs-secretome study in SCI, an increase in the neurogenesis growth factors nestin, BDNF, and GDNF. Cunningham et al[3] state that neurogenesis in brain ischemia is influenced by an increase in BDNF and GDNF after MSC-secretome administration.

Červenka et al[40] state that HNSCs-secretome increases nestin levels in brain and spinal cord trauma, and nestin is a more significant biomarker than SRY-box 2, doublecortin, tubulin-3 chain, and mic

In this study, BDNF increased in the treatment group compared to the control and normal groups. Chudickova et al[31] and Gu et al[42] state that NSC-secretome in animal models with SCI, there was an increase in BDNF at week 1 and a maximum increase at week 6 that could reduce lesion size, minimize glial scar formation, and promote axon regeneration. BDNF is produced mostly by neuronal cells and is a neurotropin that is important in the regulation of neurogenetic processes such as increased axon collateral growth, nerve branching, dendrite formation, and synaptic plasticity[43]. BDNF works through cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1R) and CB2R receptors to promote neuronal differentiation and prevent nuclear degeneration[44]. In addition, BDNF also works through the tropomyosin kinase B receptor and low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (GFR) commonly called p75[45]. Shahsavari et al[46] state that BDNF has neurophysiological functions such as nociception, cognition, and memory.

In this study, GDNF increased sharply in the treatment and control groups compared to the normal group, and the treatment group was slightly higher than the control group. Cheng et al[19] and Zhong et al[36] found that NSC-secretome increase the occurrence of axon regeneration, collateral formation, and the occurrence of new circuits in axon pathways by activating neurons and glial cells. Rosich et al[47] state that GDNF plays a role in the spinal cord in reducing lesion size, cystic cavity, increasing locomotor function improvement, nerve differentiation, chemoattractant, migration, neuroprotectant, neuroplasticity, and axon regeneration. GDNF also exerts a substantial neuroprotective effect by increasing the number of neurons in the SCI and the supraspinal central canal area[48]. GDNF acts through GFRα 1-4 receptors and is rearranged during transfection tyrosine kinase[49]. GDNF is a neurotropin involved in increasing the number of motor neurons, regenerating distal nerve axons, forming synapses, and myelination[48].

Locomotor function BBB score: Locomotor function is one of the most significant therapeutic intervention goals demonstrating the efficacy of administering HNSCs-secretome treatment in subacute SCI. Administration of HNSCs-secretome significantly improved locomotor function starting on day 7 and continuing until day 56, with mean value is 19.93 and standard deviation is 6.28. This is in accordance with previous studies that showed an increase in locomotor function improvement after NSC-secretome intervention in three studies[19,20,36].

Spinal cord lession: The treatment group showed significant differences where the treatment group showed smaller lesion sizes compared to the control group, successive mean values of 304.019 and 51.676. This is in accordance with previous studies that showed an descreased size of spinal cord lesion after MSC-secretome intervention in three studies[24,31,37].

Mechanism of SCI regeneration: The mechanism of SCI regeneration is still uncertain[3,8]. In this study, we found that analysis of the outer model, inner model, and hypothesis testing were valid. SCI regeneration begins with pro-inflammation and continues with anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, neuroangiogenesis, neurogenesis, and locomotor function. Inner model by path bootstrapping analysis found that all pathways had positive original sample values, with T-statistics more than 1.96 and P-values more than 0.05, determined to be significantly different. The relationships between latent variables in the inner model were valid based on an F square (effect size) more than 0.05, Q square (prediction relevance) more than 0, and positive path coefficients. The R square (coefficient of determination on endogenous variables) anti-inflammatory value of 0.860 indicated an effect of 86%, the anti-apoptotic value of 0.680 indicated an effect of 68%, the neuroangiogenesis value of 0.776 indicated an effect of 77%, the neurogenesis value of 0.444 indicated an influence of 44%, and the locomotory value of 0.536 indicated an influence of 53%. The outer model was valid based on the PLS SEM algorithm, the convergent validity value was more than 0.7, the AVE value was more than 0.5, and the Cronbach’s alpha value was more than 0.5. The discriminant validity based on cross-loading indicator was higher than the other construct variable indicators, while composite reliability was more than 0.7.

Assinck et al[50] state that spinal cord regeneration has five mechanisms: neuroprotection, im

These findings may identify HNSCs-secretome as a neuroprotective-neuroregenerative agent for treating SCI. The SCI regeneration mechanism started with pro-inflammation and continued with anti-inflammation, anti-apoptotic, neuroangiogenesis, neurogenesis, and locomotor function.

Globally, complete neurological recovery of spinal cord injury (SCI) is still less than 1%, and 90% experience permanent disability. The key issue is that a pharmacological neuroprotective-neuroregenerative agent and SCI regeneration mechanism have not been found. The secretomes of stem cell are an emerging neurotrophic agent, but the effect of human neural stem cells (HNSCs) secretome on SCI is still unclear.

HNSCs-secretome is expected to be the basis for use in SCI cases in the primary research stage, translational research, and neurological research for the benefit of managing SCI disease problems.

To investigate the effects of HNSCs-secretome and the regeneration mechanism on subacute SCI in rats.

An experimental study was conducted with 45 Rattus norvegicus, divided into 15 normal, 15 control (10 mL physiologic saline), and 15 treatment (30 μL HNSCs-secretome, intrathecal T10, three days post-traumatic). The strategies to increase the HNSCs-secretome production capacity include hypoxic preconditioning, tissue engineering, and growth medium composition. Locomotor function was evaluated weekly by blinded evaluators. Fifty-six days post-injury, specimens were collected, immunohistochemical-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay assessment, and hematoxylin-eosin staining. We analyzed free radical oxidative stress (F2-Isoprostanes), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-10 (IL-10), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2), nestin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and spinal cord lesion. The regeneration mechanism of SCI was analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS SEM).

The regeneration mechanism of SCI is valid by analyzed outer model, inner model, and hypothesis testing in PLS SEM, started with pro-inflammation followed by anti-inflammation, anti-apoptotic, neuroangiogenesis, neurogenesis, and locomotor function. HNSCs-secretome significantly improved locomotor recovery, reduced spinal cord lesion size, increased neurogenesis (nestin, BDNF, and GDNF), neuroangiogenesis (VEGF), anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2), anti-inflammatory (IL-10 and TGF-β), but decreased pro-inflammatory (NF-κB, MMP9, TNF-α), F2-Isoprostanes.

HNSCs-secretome as a potential agent for the treatment of SCI and uncover the SCI regeneration mechanism.

Future research investigating the chronic phase of SCI models may provide further evidence regarding the mechanism of SCI regeneration given HNSCs-secretome injection.

The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr. dr. Ismail Hadisoebroto Dilogo, Sp.OT(K) and Prof. Dr. I Ketut Sudiana, Drs., M.Si Rank for their support and advice during the research.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Indonesia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lin L, China; Wang G, China S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:620-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liau LL, Looi QH, Chia WC, Subramaniam T, Ng MH, Law JX. Treatment of spinal cord injury with mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Biosci. 2020;10:112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cunningham CJ, Redondo-Castro E, Allan SM. The therapeutic potential of the mesenchymal stem cell secretome in ischaemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:1276-1292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pajer K, Bellák T, Nógrádi A. Stem Cell Secretome for Spinal Cord Repair: Is It More than Just a Random Baseline Set of Factors? Cells. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Miranpuri GS, Nguyen J, Moreno N, Yutuc NA, Kim J, Buttar S, Brown GR, Sauer SE, Singh CK, Kumar S, Resnick DK. Folic Acid Modulates Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Expression Following Spinal Cord Injury. Ann Neurosci. 2019;26:60-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Anjum A, Yazid MD, Fauzi Daud M, Idris J, Ng AMH, Selvi Naicker A, Ismail OHR, Athi Kumar RK, Lokanathan Y. Spinal Cord Injury: Pathophysiology, Multimolecular Interactions, and Underlying Recovery Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 726] [Article Influence: 145.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Wilson JR, Kwon BK, Burns AS, Martin AR, Hawryluk G, Harrop JS. A Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Acute Spinal Cord Injury: Introduction, Rationale, and Scope. Global Spine J. 2017;7:84S-94S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pajer K, Bellák T, Nógrádi A. The mutual interaction between the host spinal cord and grafted undifferentiated stem cells fosters the production of a lesion-induced secretome. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15:1844-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cunningham CJ, Enrich MV, Pickford MM, MacIntosh-Smith W, Huang W. The Therapeutic Potential of the Stem Cell Secretome for Spinal Cord Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. OBM Neurobiol. 2020;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Dilogo IH, Fiolin J. Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Conditioned Medium (MSC-CM) in the Bone Regeneration: A Systematic Review from 2007-2018. Annu Res Rev Biol. 2019;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Vizoso FJ, Eiro N, Cid S, Schneider J, Perez-Fernandez R. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies in Regenerative Medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 548] [Cited by in RCA: 877] [Article Influence: 109.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim OH, Hong HE, Seo H, Kwak BJ, Choi HJ, Kim KH, Ahn J, Lee SC, Kim SJ. Generation of induced secretome from adipose-derived stem cells specialized for disease-specific treatment: An experimental mouse model. World J Stem Cells. 2020;12:70-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Honmou O, Yamashita T, Morita T, Oshigiri T, Hirota R, Iyama S, Kato J, Sasaki Y, Ishiai S, Ito YM, Namioka A, Namioka T, Nakazaki M, Kataoka-Sasaki Y, Onodera R, Oka S, Sasaki M, Waxman SG, Kocsis JD. Intravenous infusion of auto serum-expanded autologous mesenchymal stem cells in spinal cord injury patients: 13 case series. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2021;203:106565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Santos MFD, Roxo C, Solá S. Oxidative-Signaling in Neural Stem Cell-Mediated Plasticity: Implications for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yang C, Sun J, Tian Y, Li H, Zhang L, Yang J, Wang J, Zhang J, Yan S, Xu D. Immunomodulatory Effect of MSCs and MSCs-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2021;12:714832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fakhri S, Sabouri S, Kiani A, Farzaei MH, Rashidi K, Mohammadi-Farani A, Mohammadi-Noori E, Abbaszadeh F. Intrathecal administration of naringenin improves motor dysfunction and neuropathic pain following compression spinal cord injury in rats: relevance to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Korean J Pain. 2022;35:291-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bavarsad K, Barreto GE, Hadjzadeh MA, Sahebkar A. Protective Effects of Curcumin Against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in the Nervous System. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:1391-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang C, Lu CF, Peng J, Hu CD, Wang Y. Roles of neural stem cells in the repair of peripheral nerve injury. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:2106-2112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cheng Z, Bosco DB, Sun L, Chen X, Xu Y, Tai W, Didier R, Li J, Fan J, He X, Ren Y. Neural Stem Cell-Conditioned Medium Suppresses Inflammation and Promotes Spinal Cord Injury Recovery. Cell Transplant. 2017;26:469-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rong Y, Liu W, Wang J, Fan J, Luo Y, Li L, Kong F, Chen J, Tang P, Cai W. Neural stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles attenuate apoptosis and neuroinflammation after traumatic spinal cord injury by activating autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang L, Pei S, Han L, Guo B, Li Y, Duan R, Yao Y, Xue B, Chen X, Jia Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Reduce A1 Astrocytes via Downregulation of Phosphorylated NFκB P65 Subunit in Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;50:1535-1559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen Y, Tian Z, He L, Liu C, Wang N, Rong L, Liu B. Exosomes derived from miR-26a-modified MSCs promote axonal regeneration via the PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway following spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huang JH, Yin XM, Xu Y, Xu CC, Lin X, Ye FB, Cao Y, Lin FY. Systemic Administration of Exosomes Released from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Attenuates Apoptosis, Inflammation, and Promotes Angiogenesis after Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:3388-3396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cizkova D, Cubinkova V, Smolek T, Murgoci AN, Danko J, Vdoviakova K, Humenik F, Cizek M, Quanico J, Fournier I, Salzet M. Localized Intrathecal Delivery of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Conditioned Medium Improves Functional Recovery in a Rat Model of Spinal Cord Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Huang JH, Xu Y, Yin XM, Lin FY. Exosomes Derived from miR-126-modified MSCs Promote Angiogenesis and Neurogenesis and Attenuate Apoptosis after Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. Neuroscience. 2020;424:133-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Borhani-Haghighi M, Navid S, Mohamadi Y. The Therapeutic Potential of Conditioned Medium from Human Breast Milk Stem Cells in Treating Spinal Cord Injury. Asian Spine J. 2020;14:131-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhou X, Chu X, Yuan H, Qiu J, Zhao C, Xin D, Li T, Ma W, Wang H, Wang Z, Wang D. Mesenchymal stem cell derived EVs mediate neuroprotection after spinal cord injury in rats via the microRNA-21-5p/FasL gene axis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;115:108818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Muhammad M. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha: A Major Cytokine of Brain Neuroinflammation. In: Behzadi P. Cytokines. United Kingdom: IntechOpen, 2020: 1-14. |

| 29. | Ullah M, Liu DD, Thakor AS. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Homing: Mechanisms and Strategies for Improvement. iScience. 2019;15:421-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 61.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xin W, Qiang S, Jianing D, Jiaming L, Fangqi L, Bin C, Yuanyuan C, Guowang Z, Jianguang X, Xiaofeng L. Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Attenuate Blood-Spinal Cord Barrier Disruption via the TIMP2/MMP Pathway After Acute Spinal Cord Injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58:6490-6504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chudickova M, Vackova I, Machova Urdzikova L, Jancova P, Kekulova K, Rehorova M, Turnovcova K, Jendelova P, Kubinova S. The Effect of Wharton Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Their Conditioned Media in the Treatment of a Rat Spinal Cord Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hellenbrand DJ, Reichl KA, Travis BJ, Filipp ME, Khalil AS, Pulito DJ, Gavigan AV, Maginot ER, Arnold MT, Adler AG, Murphy WL, Hanna AS. Sustained interleukin-10 delivery reduces inflammation and improves motor function after spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shen H, Xu B, Yang C, Xue W, You Z, Wu X, Ma D, Shao D, Leong K, Dai J. A DAMP-scavenging, IL-10-releasing hydrogel promotes neural regeneration and motor function recovery after spinal cord injury. Biomaterials. 2022;280:121279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Li S, Gu X, Yi S. The Regulatory Effects of Transforming Growth Factor-β on Nerve Regeneration. Cell Transplant. 2017;26:381-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Liu W, Wang Y, Gong F, Rong Y, Luo Y, Tang P, Zhou Z, Xu T, Jiang T, Yang S, Yin G, Chen J, Fan J, Cai W. Exosomes Derived from Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells Repair Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury by Suppressing the Activation of A1 Neurotoxic Reactive Astrocytes. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36:469-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhong D, Cao Y, Li CJ, Li M, Rong ZJ, Jiang L, Guo Z, Lu HB, Hu JZ. Neural stem cell-derived exosomes facilitate spinal cord functional recovery after injury by promoting angiogenesis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2020;245:54-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sun G, Li G, Li D, Huang W, Zhang R, Zhang H, Duan Y, Wang B. hucMSC derived exosomes promote functional recovery in spinal cord injury mice via attenuating inflammation. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2018;89:194-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Tsai MJ, Liou DY, Lin YR, Weng CF, Huang MC, Huang WC, Tseng FW, Cheng H. Attenuating Spinal Cord Injury by Conditioned Medium from Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J Clin Med. 2018;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Huang JH, Fu CH, Xu Y, Yin XM, Cao Y, Lin FY. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Epidural Fat-Mesenchymal Stem Cells Attenuate NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Improve Functional Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury. Neurochem Res. 2020;45:760-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Červenka J, Tylečková J, Kupcová Skalníková H, Vodičková Kepková K, Poliakh I, Valeková I, Pfeiferová L, Kolář M, Vaškovičová M, Pánková T, Vodička P. Proteomic Characterization of Human Neural Stem Cells and Their Secretome During in vitro Differentiation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:612560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gilbert EAB, Lakshman N, Lau KSK, Morshead CM. Regulating Endogenous Neural Stem Cell Activation to Promote Spinal Cord Injury Repair. Cells. 2022;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Gu M, Gao Z, Li X, Guo L, Lu T, Li Y, He X. Conditioned medium of olfactory ensheathing cells promotes the functional recovery and axonal regeneration after contusive spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 2017;1654:43-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Leech KA, Hornby TG. High-Intensity Locomotor Exercise Increases Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Individuals with Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:1240-1248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ferreira FF, Ribeiro FF, Rodrigues RS, Sebastião AM, Xapelli S. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Role in Cannabinoid-Mediated Neurogenesis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Mudjihartini N. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) dan proses penuaan: sebuah tinjauan. J Biomedika dan Kesehat. 2021;4:120-129. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 46. | Shahsavari F, Abbasnejad M, Esmaeili-Mahani S, Raoof M. The ability of orexin-A to modify pain-induced cyclooxygenase-2 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression is associated with its ability to inhibit capsaicin-induced pulpal nociception in rats. Korean J Pain. 2022;35:261-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Rosich K, Hanna BF, Ibrahim RK, Hellenbrand DJ, Hanna A. The Effects of Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor after Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:3311-3325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Deng LX, Liu NK, Wen RN, Yang SN, Wen X, Xu XM. Laminin-coated multifilament entubulation, combined with Schwann cells and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, promotes unidirectional axonal regeneration in a rat model of thoracic spinal cord hemisection. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16:186-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Fielder GC, Yang TW, Razdan M, Li Y, Lu J, Perry JK, Lobie PE, Liu DX. The GDNF Family: A Role in Cancer? Neoplasia. 2018;20:99-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Assinck P, Duncan GJ, Hilton BJ, Plemel JR, Tetzlaff W. Cell transplantation therapy for spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:637-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 618] [Article Influence: 77.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |