Published online Jun 18, 2021. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v12.i6.412

Peer-review started: February 19, 2021

First decision: May 3, 2021

Revised: May 5, 2021

Accepted: June 4, 2021

Article in press: June 4, 2021

Published online: June 18, 2021

Processing time: 111 Days and 21.3 Hours

Fellowship directors (FDs) in sports medicine influence the future of trainees in the field of orthopaedics. Understanding the characteristics these leaders share must be brought into focus. For all current sports medicine FDs, our group analyzed their demographic background, institutional training, and academic experience.

To serve as a framework for those aspiring to achieve this position in orthopaedics and also identify opportunities to improve the position.

Fellowship programs were identified using both the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine and the Arthroscopy Association of North America Sports Medicine Fellowship Directories. The demographic and educational background data for each FD was gathered via author review of current curriculum vitae (CVs). Any information that was unavailable on CV review was gathered from institutional biographies, Scopus Web of Science, and emailed questionnaires. To ensure the collection of as many data points as possible, fellowship program coordinators, orthopaedic department offices and FDs were directly contacted via phone if there was no response via email. Demographic information of interest included: Age, gender, ethnicity, residency/fellowship training, residency/fellowship graduation year, year hired by current institution, time since training completion until FD appointment, length in FD role, status as a team physician and H-index.

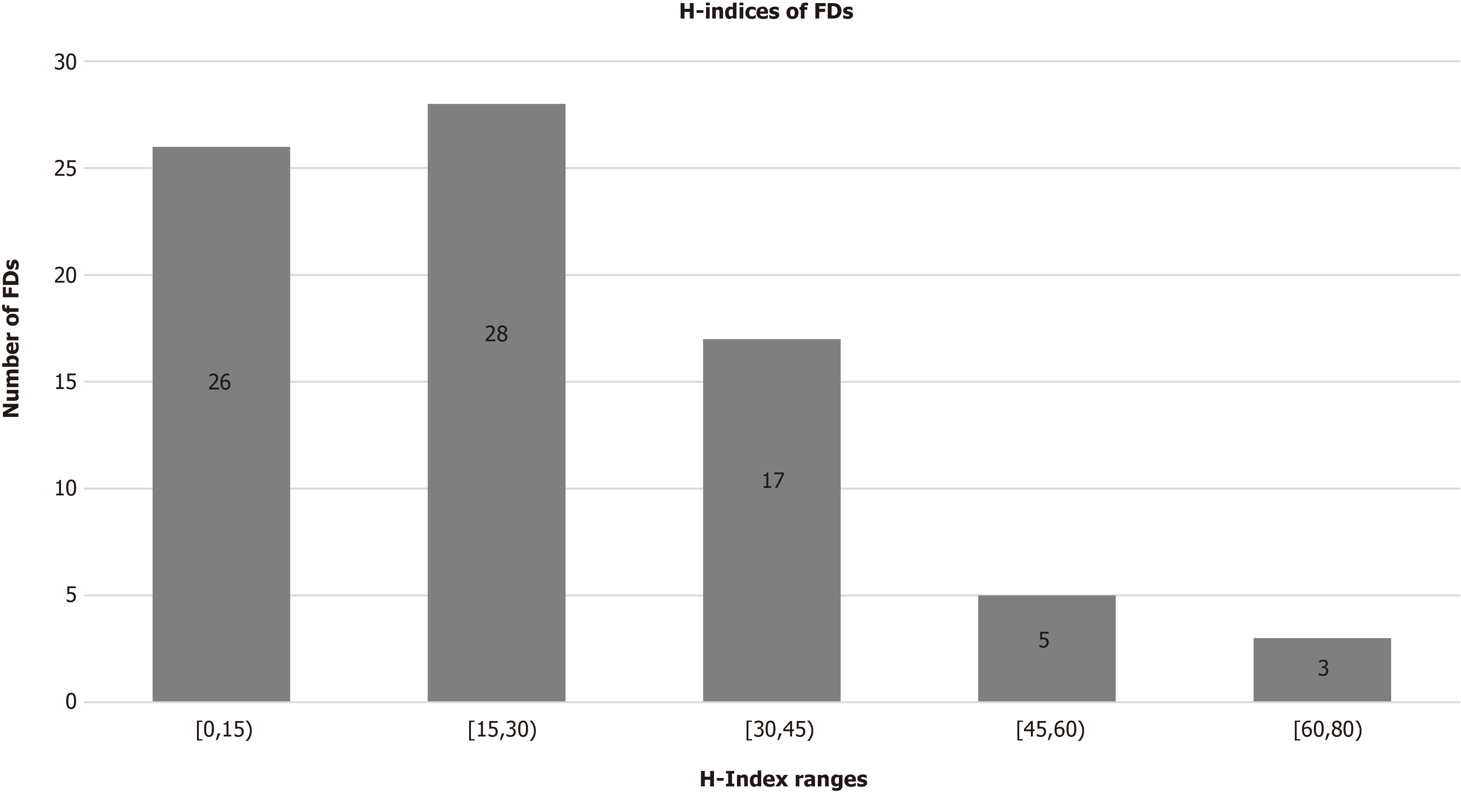

Information was gathered for 82 FDs. Of these, 97.5% (n = 80) of the leadership were male; 84.15% (n = 69) were Caucasian, 7.32% (n = 6) were Asian-American, 2.44% (n = 2) were Hispanic and 2.44% (n = 2) were African American, and 3.66% (n = 3) were of another race or ethnicity. The mean age of current FDs was 56 years old (± 9.00 years), and the mean Scopus H-index was 23.49 (± 16.57). The mean calendar years for completion of residency and fellowship training were 1996 (± 15 years) and 1997 (± 9.51 years), respectively. The time since fellowship training completion until FD appointment was 9.77 years. 17.07% (n = 14) of FDs currently work at the same institution where they completed residency training; 21.95% (n = 18) of FDs work at the same institution where they completed fellowship training; and 6.10% (n = 5) work at the same institution where they completed both residency and fellowship training. Additionally, 69.5% (n = 57) are also team physicians at the professional and/or collegiate level. Of those that were found to currently serve as team physicians, 56.14% (n = 32) of them worked with professional sports teams, 29.82% (n = 17) with collegiate sports teams, and 14.04% (n = 8) with both professional and collegiate sports teams. Seven residency programs produced the greatest number of future FDs, included programs produced at least three future FDs. Seven fellowship programs produced the greatest number of future FDs, included programs produced at least four future FDs. Eight FDs (9.75%) completed two fellowships and three FDs (3.66%) finished three fellowships. Three FDs (3.66%) did not graduate from any fellowship training program. The Scopus H-indices for FDs are displayed as ranges that include 1 to 15 (31.71%, n = 26), 15 to 30 (34.15%, n = 28), 30 to 45 (20.73%, n = 17), 45 to 60 (6.10%, n = 5) and 60 to 80 (3.66%, n = 3). Specifically, the most impactful FD in research currently has a Scopus H-index value of 79. By comparison, the tenth most impactful FD in research had a Scopus H-index value of 43 (accessed December 1, 2019).

This study provides an overview of current sports medicine FDs within the United States and functions as a guide to direct initiatives to achieve diversity equality.

Core Tip: This retrospective study provides an overview of current fellowship directors (FDs) within sports medicine in the United States. Currently, orthopaedics has lower percentages of females and minorities in leadership roles than many other specialties. Gender and racial diversity of these specialties should be a continued focus for improvement. Overall, the trends identified in this study serve as objective data on current FDs within sports medicine. These trends could function as a guide for individuals who strive to become academic leaders in sports medicine orthopaedics as well as direct initiatives to achieve diversity equality.

- Citation: Schiller NC, Sama AJ, Spielman AF, Donnally III CJ, Schachner BI, Damodar DM, Dodson CC, Ciccotti MG. Trends in leadership at orthopaedic surgery sports medicine fellowships. World J Orthop 2021; 12(6): 412-422

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v12/i6/412.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v12.i6.412

In medicine, those in leadership roles share certain characteristics that are gained from their formal training and mentors. Specifically, the fellowship director (FD) is one that will be a significant influence on many aspiring leaders. Potential factors that help physicians reach leadership positions are the ability to influence peers, develop research and educate the next generation of physicians. Through academic training, societal and community involvement, and clinical experience, such individuals decisively develop a set of leadership skills. However, the objective standards that serve as a foundation for these leaders, and sets them apart from others, remains unclear. Furthermore, it seems that developing orthopaedic surgeons pursuing these leadership positions lack objective directions on how to achieve them.

Within orthopaedics, sports medicine FDs oversee decisions that have an effect on current and future trainees. An assessment of the shared attributes associated with these individuals that achieve professional accomplishment to this extent needs to be developed. This review evaluated objective information on the traits and attributes of these leaders. Particularly, this review identifies and examines the demographics, academic experience, and institutional training backgrounds of current sports medicine FDs in the United States. Overall, this study may serve as a guide for aspiring leaders on how to achieve leadership positions in orthopaedic sports medicine and identify opportunities to improve the FD position, specifically with regards to diversifying leaders’ racial, gender, training, and research backgrounds.

The American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) and the Arthroscopy Association of North America Sports Medicine Fellowship Directories for 2019-2020 were queried in order to locate all sports medicine orthopaedic surgery fellowships in the United States. For each program, all listed FDs were included. The demographic and educational background data for each FD was gathered via author review of current curriculum vitae (CVs). Any information that was unavailable on CV review was gathered from institutional biographies, Scopus Web of Science, and emailed questionnaires sent to fellowship administrators. To ensure the collection of as many data points as possible, fellowship program coordinators, orthopaedic department offices and FD were directly contacted via phone if there was no response via email. The demographic information of interest included: Age, gender, race/ethnicity, former residency and fellowship training location, the year of residency and fellowship graduation, year hired by current institution, time since residency and fellowship completion until FD appointment, length in FD role, each individual’s H-index and status as a team physician at either the professional or collegiate level. Team physician roles included in the study were ‘team physician’, ‘head team physician’ or ‘assistant team physician’.

To obtain the individual H-index for each FD, the Scopus database (Elsevier BV, Waltham, MA, United States) was queried to access their research specific information. This database has a search engine feature that operates through an extensive repository of peer-reviewed scientific literature with a citation tracking component. Scopus was employed to retrieve the H-index for every FD in the study.

Pearson correlation coefficients were determined via Statistical Analytics System (9.4) software. Data was interpreted according to Mukaka’s guide for correlation coefficients[1]. Values under 0.3, 0.3 to 0.5, 0.5 to 0.7, 0.7 to 0.9 and greater than 0.90 are indicative of negligible, low, moderate, high, and very high positive correlation respectively.

Of 82 FDs were included in this study. The demographic information includes age, gender, race/ethnicity, and mean Scopus H-index. This information is summarized in Table 1.

| Demographics | |

| Male | 80 (97.5%) |

| Female | 2 (2.5%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 84.15% (n = 69) |

| Asian-Americans | 7.32% (n = 6) |

| Hispanic/Latinos | 2.44% (n = 2) |

| African American | 2.44% (n = 2) |

| Other | 3.66% (n = 3) |

| Mean age, yr | 56 ± 9.00 (n = 76) |

| Mean FD Scopus H-index | 23.49 ± 16.57 (n = 81) |

Table 2 presents a detailed overview of educational, employment, and leadership progression of sports medicine FDs, including mean calendar years for completion of residency and fellowship training, mean duration from fellowship graduation until FD appointment, mean duration of employment for a FD at his/her current institution, mean duration that an FD has held his/her current position, and the average time from initial hire until FD appointment. Table 2 also details the percentages of FDs who, at the time of the study, were working at the same institution where he/she completed their residency training, fellowship training, or both residency and fellowship training. Correlation of research productivity, which was measured in the form of Scopus H-indices, is included in Table 2.

| Education and employment progression | mean ± SD |

| Mean calendar year of residency graduation | 1996 ± 15.00 (n = 73) |

| Mean calendar year of fellowship graduation | 1997 ± 9.51 (n = 73) |

| Mean duration from fellowship graduation to earning position of FD | 9.77 yr ± 7.33 (n = 57) |

| Mean duration of employment at current institution | 18.20 yr ± 9.12 (n = 65) |

| Mean duration that FD has held position as FD | 13.14 yr ± 9.54 (n = 59) |

| Mean time from year of hire by current institution to year promoted to FD | 4.72 yr ± 7.93 (n = 64) |

| Institutional loyalty | n (%) |

| FDs currently working at same institution as Residency training | 14 (17.07) |

| FDs currently working at same institution as Fellowship training | 18 (21.95) |

| FDs currently working at same institution as both Residency and Fellowship training | 5 (6.10) |

| Correlation of research productivity | r (P value) |

| Years as FD vs Scopus H-index | 0.29 (0.02) |

| Age vs Scopus H-index | 0.38 (0.001)1 |

Table 3 demonstrates FD team physician status. Furthermore, team physician status is categorized into professional and collegiate team physicians, as well as sport specific involvement.

| Team physician roles | |

| Fellowship directors’ team physician status | n = 82 |

| Yes | 57 (69.51) |

| No | 25 (30.49) |

| Professional vs collegiate | n = 57 |

| Professional | 32 (56.14) |

| Collegiate | 17 (29.82) |

| Both | 8 (14.04) |

| Sport | n = 103 |

| University-wide Athletics | 26 (25.24) |

| Professional other | 23 (22.33) |

| Professional baseball | 20 (19.41) |

| Professional football | 16 (15.53) |

| Professional hockey | 8 (7.77) |

| Professional basketball | 7 (6.80) |

| Professional soccer | 3 (2.91) |

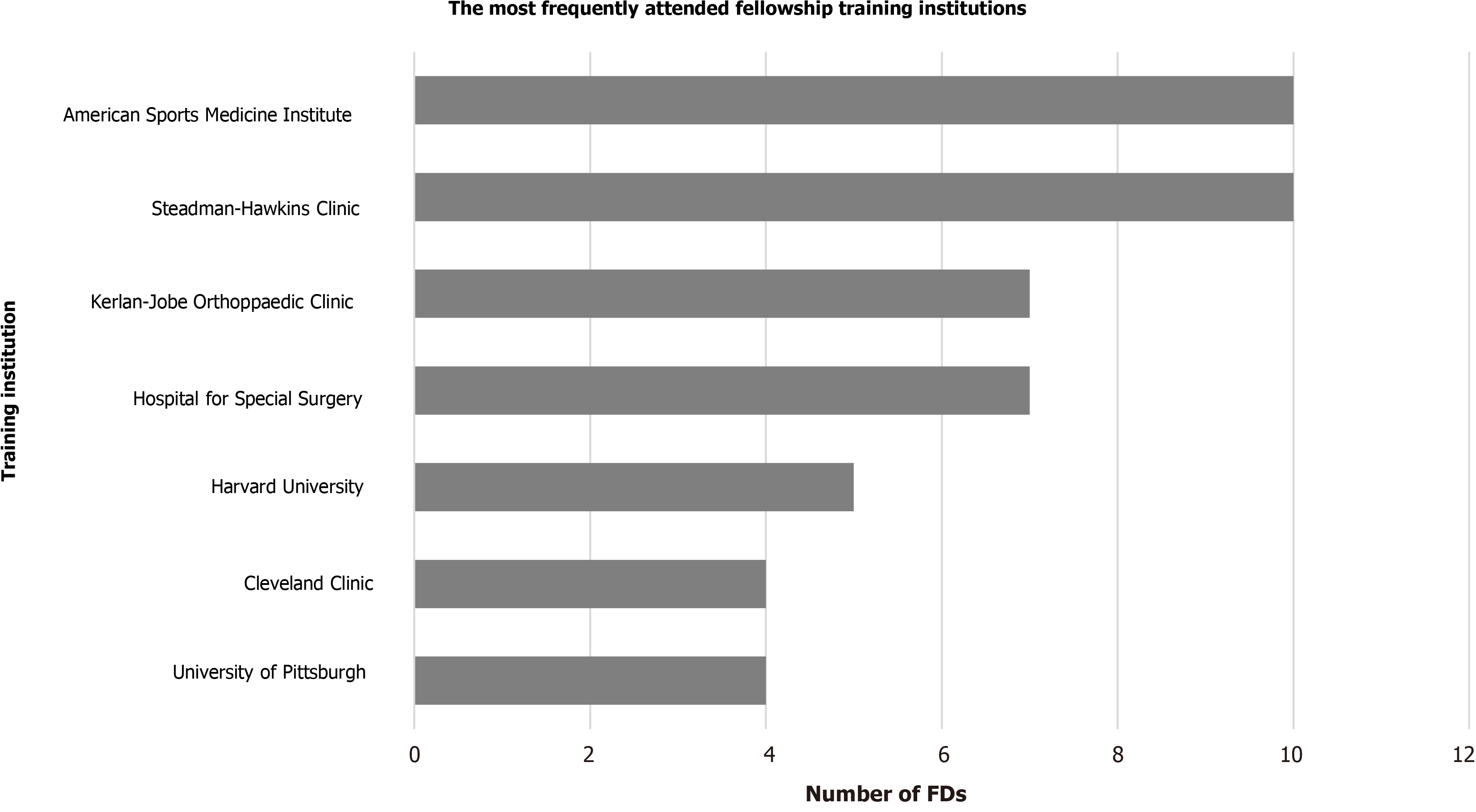

Figures 1 and 2 represent the most attended orthopaedic surgery residency and fellowship training programs, respectively. Figure 1 includes the orthopaedic surgery residency programs which trained at least 3 current FDs. Figure 2 includes the orthopaedic surgery fellowship programs which trained at least 4 current. Notably, 8 FDs (9.8%) completed two fellowships and 3 FDs (3.7%) finished three fellowships. Three FDs (3.7%) did not complete any formal orthopaedic surgery fellowship training.

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution the Scopus H-indices for FDs in the form of ranges. In terms of Scopus H-indices, the ten most impactful sports medicine FDs in research had a Scopus H-index values between 43 and 79. (data retrieved December 1, 2019).

Currently, literature documenting the necessary training and skill development of physician leaders in other surgical specialties is limited[2-5]. One study in the field of general surgery, discussed the relationship between past residents’ rank lists to future academic career path[6]. Plastic surgery is another subspecialized field that has also evaluated leadership roles and trends in characteristics[7,8]. Previous studies in orthopaedics have considered the pertinent motivating factors impacting the applicant selection process of residency and FDs, as well as the selection process of medical students and residents when considering orthopaedic surgery as a specialty[9-15]. In discussions on appropriate or discrepant representation of gender and cultural diversity, the leadership within orthopaedics has come into focus[16-19]. Two other studies have described demographic characteristics for spine fellowship leaders and adult reconstruction FDs which similarly noted FDs are more likely to have graduated from certain residency and fellowship programs[7,20]. As in this sports medicine cohort, the spine and adult reconstruction cohorts might attract applicants with a predilection to later seek academic leadership roles post-training[7,19,20].

Academic careers within medicine are founded upon clinical service, teaching, and research. Involvement and, naturally, productivity in research is a significant metric among those who achieve academic leadership positions. One study, by Cvetanovich et al[21] concluded that a higher cumulative h index correlated with higher academic rank among AOSSM sports medicine fellowship faculty[21]. Our analysis reveals a mean Scopus H-index of 23.49 (± 16.57) for sports medicine FDs which is considered high. Paralleled to these findings in research productivity, our results indicated that clinical experience is a crucial factor to sports medicine leadership appointment as the mean duration from fellowship graduation to FD appointment was 9.77 years (± 7.33 years). This data is similar to the results in the other orthopaedics FD demographic studies. Spine FDs’ mean duration from fellowship graduation to FD appointment was 8.59 years, while, adult reconstruction FD’s had a mean duration 9.55 years[7,20]. The average age of sports medicine FDs was 56 years-old. Compared to an average age 52.85 years and 52.60 years for spine and adult reconstruction FDs, respectively[7,20].

Based on our data, a select group of residency and fellowship training programs have a predilection for producing future sports medicine FDs. The residency program most commonly attended by current sports medicine FDs produced 8 current directors, while six other residency programs produced between 3 and 4 current FDs each. Interestingly, 8 FDs (9.75%) graduated from two fellowships and 3 FDs (3.66%) graduated from three fellowships. Unusually, 3 FDs (3.66%) did not undergo any post-residency training most likely because they completed their training before the 1990s.

In our study, we noted that 91.5% (n = 76) of FDs were AOSSM members. While subspeciality society membership is not a requirement to be in an academic leadership role, the benefits of such societies can give orthopaedic surgeons more access to collaborative research, networking opportunities, team physician skills as well as committee leadership positions. These early leadership roles can develop the necessary skillset required to transition into a FD role later in one’s career. AOSSM is a society with a mission to foster the development and growth of all those affiliated in the care of athletes, and through this affords an aspiring FD access to the annual meeting, scholarships, faculty resources, online education and recertification aid. These many facets of the society all likely contribute to the growth of these surgeons into academic leaders. Specifically, words from the presidential address at 43rd annual AOSSM meeting highlight these concepts well “AOSSM inspires all of us to participate in the organization, strive for excellence in the care of our patients, produce outstanding research, and share knowledge and educate ourselves.”[22]

Among fellowship programs attended, two programs each produced 10 current sports medicine FDs, while the next five programs produced between 4 and 7 FDs each. Overall, the top seven fellowship programs produced 57.32% (n = 47) of all the current sports medicine FDs. Interestingly, there was significant overlap in the training sites for both the sports and spine leadership training and show some overlap between sports and adult reconstruction[7,20]. This may indicate that attending specific fellowship training programs may correlate with future academic leadership possibilities. These programs potentially offer specific training curricula that foster the development of vital skills that translate well into leadership roles, perhaps through mentor style training between residents of different training levels and attendings alike. It is also likely that these institutions provide increased access to scholarly activity and have more research staff. This is supported by a study that included all faculty at United States adult reconstruction fellowship programs that indicated that most of the literature in adult reconstruction is generated from a small subset of academic institutions[23]. Thus, orthopaedic surgeons in-training interested in pursuing academic leadership positions may be more incentivized to select programs that promote orthopaedic surgery research. Program reputation and professional networks might serve as additional factors that could potentially play a role in the association of these specific programs with current FDs. These are just some possible explanations for our findings, however this is likely multifactorial. Nonetheless, our analysis supports the correlation that attending and graduating from specific training programs has a predilection to produce future program directors.

Of the major professional sports in America, sports FDs most commonly served as team physicians in baseball, then football, followed by hockey, basketball and soccer. It was also more likely that FDs also served as team physicians for university-wide athletics and provide care for all affiliated sports teams. This is likely due to the collaborative care philosophy amongst the various team physicians part of an academic institution or because part of being the FD for an academic institution includes the responsibilities of treating all types of athletes in all types of sports.

While literature exists regarding the legality, responsibilities, ethics and financial aspects of being a team physician, currently, there is no literature describing how an orthopaedic surgeon becomes a team physician and if leadership within the field tends to influence team physician status[24-28]. Our results showed that 69.51% (n = 57) of current sports medicine FDs also served as team physicians at the professional or collegiate level or both. It is possible that the percentage of FDs as team physicians is likely not the same as non-FD sports medicine surgeons. While having a leadership position, such as FD, potentially opens more opportunities for sports medicine physicians, it may also give them increased options to be involved as a team physician. This may be due to the similar leadership skills that are required as a FD and team physician. Alternatively, it may be that athletic teams, particularly at the more elite levels, desire to have surgeons with leadership roles caring for their organizations. Aspiring sports medicine physicians, therefore, may find that being a FD might possibly enhance their chances of becoming a team physician or vice versa. Therefore, a better understanding of these objective leadership qualities may enhance the likelihood of a sports medicine surgeon achieving either/both of those roles.

Our study indicates that there is a significant gender disparity in the FD role, as females were notably under-represented at only 2.5% (n = 2) of all the current sports medicine FDs. This is actually a better representation that what was observed among adult reconstruction FDs, where no females were in an FD position at the time of the study[20]. As the healthcare profession advances, there has been a focus on the importance of overall diversity. Specifically, gender diversity has been addressed in several healthcare specialties with a broad range of findings[17,29]. Currently, orthopaedic surgery has one of the poorest ratios of female to male residents as compared to other specialties in medicine[17,29]. Although the total amount of orthopaedic surgery female residents has increased over the past 10 years, the corresponding percentage change is not as significant as other historically male-dominated specialties[29]. Moreover, certain orthopaedic subspecialties, such as sports medicine, continue to have decreased female involvement[29]. This may represent the inappropriate but historically prevalent perspective of the physicality of orthopaedics and sports medicine specifically. In addition, because of historical restrictions on females in male locker rooms, particularly at the most elite levels, gender inequality has existed in the team physician role. Most recently, the current leadership of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and more specifically the AOSSM, have identified this issue and have focused on achieving gender equality. This is evidenced by the recent female presidents of both of these organizations, the establishment of Diversity Committees within each societies’ infrastructure and the creation of educational programs in their regional, national and international meetings focused on diversity equality. In a study by Ence et al[30] it was specifically reported that a lower median H-index was observed when comparing female orthopaedic surgeons to their male colleagues[30]. And yet, most certainly some of the most impactful and important research is created by female investigators. This could be a critical issue as our study shows research productivity is a key feature to achieving leadership roles. Furthermore, the previous gender barriers in the team physician role are being remo

Our study also considered racial and ethnic diversity, demonstrating that sports medicine leadership at the FD level also lacks underrepresented minorities. Among the sports medicine FDs in the study, only 7.32% (n = 6) were Asian-Americans, 2.44% (n = 2) were Hispanic/Latino, 2.44% (n = 2) were African American and 3.66% (n = 3) were of another race or ethnicity. One study from 1999[32] and another from 2004[33], reviewed the disparities in underrepresented minorities within the field of orthopaedics, and may have played a part in progressive changes that followed. Okike et al[34] described that total minority representation in orthopaedic surgery averaged 20.2% from the years 2001 to 2008, this included 11.7% Asians or Asian-Americans, 4.0% African Americans, and 3.8% Hispanics. Upon reviewing their data, the authors believed that this was an improvement compared to years prior with regards to representation of minorities among orthopaedic residents[34]. Adelani et al[35] subsequently illustrated a regression in minority representation. The number of programs per year with more than one underrepresented minority resident fell from 61 programs in 2002 to 53 programs in 2016 and reached as low as 31 programs in 2010. Likewise, the number of programs per year without a single underrepresented minority resident rose from 40 programs in 2002 to 60 programs in 2016 and reached 76 programs in 2011. In the end, the study called for a more detailed evaluation of program-level diversity and its impact on the recruitment of underrepresented minorities to orthopaedic surgery[35]. Our data identified a similar trend to those previously reported. As the orthopaedic community continues to adapt, a focus on diversity will remain pivotal to the advancement of any healthcare system that desires to appropriately represent the population it serves. Focusing on increasing the number of underrepresented minorities in leadership positions may be one way to begin to address these disparities.

This study does have several limitations. One limitation was the use of CV for data collection. Given that CV’s are usually self-reported, there is an inherent potential bias with the possibility of reporting errors including duplication of events, failure to list appropriate research or leadership activities, and outdated information. Furthermore, this cross-sectional study design only provides information on sports FDs at a single point in time. Future studies may opt to complete a year-by-year comparison to understand the changes in the leadership over time. Lastly, a subset of sports medicine trained orthopaedic surgeons may have selected specific programs with academic career aspirations in mind with the understanding that certain training institutions tend to produce future FDs and leaders.

This study provides an assessment of current FDs within sports medicine in the United States. Currently, the field of orthopaedics has lower percentages of females and minorities in leadership roles. Gender and racial diversity of these specialties should be a continued focus. Overall, the trends identified in this study serve as objective data on current FDs within sports medicine. These trends could function as a guide for individuals who strive to become academic leaders in sports medicine orthopaedics as well as direct initiatives to achieve diversity equality.

Fellowship directors (FDs) in sports medicine influence the future of trainees in the field of orthopaedics. Understanding the characteristics these leaders share must be brought into focus. Currently, there is little research regarding the demographic landscape of these leaders.

The current literature highlighted a lack of research specifically using objective data analyze sports medicine FDs. By adding to this gap in the literature, this study may promote future research towards understanding further the requirements and qualifications needed to hold a leadership position in orthopedic surgery.

This study aimed to analyze the demographic background, institutional training, and academic experience for all current sports medicine FDs.

A national orthopedic surgery sports medicine fellowship program directory was used to incorporate all United States fellowships and their respective FDs. Demographic information of interest included: Age, gender, ethnicity, residency/fellowship training, residency/fellowship graduation year, year hired by current institution, time since training completion until FD appointment, length in FD role, status as a team physician and H-index. This information was collected via online resources, emailed questionnaires, phone call and current curriculum vitae. Data was then complied and reviewed to evaluate for trends among sports medicine FDs. This is a novel research method for analyzing the current cohort of sports medicine FDs.

Of 82 FDs were incorporated into the study, 97.5% of which were male. 84.15% identified as Caucasian, 7.32% as Asian-American, 2.44% as African American, and 2.44% as Hispanic, and 3.66% were of another race or ethnicity. The mean age of current FDs was 56 years old, and the mean Scopus H-index was 23.49. 45.12% completed their residency training, fellowship training or both at the same institution where they currently work. Additionally, 69.5% are also team physicians at the professional and/or collegiate level. Seven residency programs least three future FDs. While seven fellowship programs produced at least four future FDs. 9.75% of FDs completed two fellowships and 3.66% of FDs completed three fellowships. 3.66% of FDs did not graduate from any fellowship training program.

This study provides an overview of current sports medicine FDs within the United States and functions as a guide to direct initiatives to achieve diversity equality. This study may be referenced to help dictate efforts to address disparities in gender and racial equality in orthopedic surgery.

The direction of future research should focus on the progression of leaders in orthopedic surgery, evaluating the changes in demographic and academic backgrounds of leaders in subsequent years. Applying this methodology longitudinally may prove paramount in reaching the goals the field of orthopedic surgery aims to achieve.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: SATHISH HS S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Mukaka MM. Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J. 2012;24:69-71. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Itani KM, Liscum K, Brunicardi FC. Physician leadership is a new mandate in surgical training. Am J Surg. 2004;187:328-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Büchler P, Martin D, Knaebel HP, Büchler MW. Leadership characteristics and business management in modern academic surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:149-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Patel VM, Warren O, Humphris P, Ahmed K, Ashrafian H, Rao C, Athanasiou T, Darzi A. What does leadership in surgery entail? ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:876-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Daniels AH, DePasse JM, Magill ST, Fischer SA, Palumbo MA, Ames CP, Hart RA. The Current State of United States Spine Surgery Training: A Survey of Residency and Spine Fellowship Program Directors. Spine Deform. 2014;2:176-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Beninato T, Kleiman DA, Zarnegar R, Fahey TJ 3rd. Can Future Academic Surgeons be Identified in the Residency Ranking Process? J Surg Educ. 2016;73:788-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Donnally CJ 3rd, Schiller NC, Butler AJ, Sama AJ, Bondar KJ, Goz V, Shenoy K, Vaccaro AR, Hilibrand AS. Trends in Leadership at Spine Surgery Fellowships. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2020;45:E594-E599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Addona T, Polcino M, Silver L, Taub PJ. Leadership trends in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:750-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rao RD, Khatib ON, Agarwal A. Factors Motivating Medical Students in Selecting a Career Specialty: Relevance for a Robust Orthopaedic Pipeline. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:527-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Matson AP, Kavolus JJ, Byrd WA, Leversedge FJ, Brigman BE. Influence of Trainee Experience on Choice of Orthopaedic Subspecialty Fellowship. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26:e62-e67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kavolus JJ, Matson AP, Byrd WA, Brigman BE. Factors Influencing Orthopedic Surgery Residents' Choice of Subspecialty Fellowship. Orthopedics. 2017;40:e820-e824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schrock JB, Kraeutler MJ, Dayton MR, McCarty EC. A Cross-sectional Analysis of Minimum USMLE Step 1 and 2 Criteria Used by Orthopaedic Surgery Residency Programs in Screening Residency Applications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:464-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grabowski G, Walker JW. Orthopaedic fellowship selection criteria: a survey of fellowship directors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:e154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Anderson DG, Silber J, Vaccaro A. Spine training. Spine surgery fellowships: perspectives of the fellows and directors. Spine J. 2001;1:229-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Baweja R, Kraeutler MJ, Mulcahey MK, McCarty EC. Determining the Most Important Factors Involved in Ranking Orthopaedic Sports Medicine Fellowship Applicants. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5:2325967117736726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ford HR, Upperman JS, Lim JC. What Does It Mean to Be an Underrepresented Minority Leader in Surgery? In: Kibbe MR, Chen H, editors. Leadership in Surgery. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015: 183-193. |

| 17. | Rohde RS, Wolf JM, Adams JE. Where Are the Women in Orthopaedic Surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1950-1956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Filiberto AC, Le CB, Loftus TJ, Cooper LA, Shaw C, Sarosi GA Jr, Iqbal A, Tan SA. Gender differences among surgical fellowship program directors. Surgery. 2019;166:735-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rynecki ND, Krell ES, Potter JS, Ranpura A, Beebe KS. How Well Represented Are Women Orthopaedic Surgeons and Residents on Major Orthopaedic Editorial Boards and Publications? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:1563-1568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Schiller NC, Donnally CJ 3rd, Sama AJ, Schachner BI, Wells ZS, Austin MS. Trends in Leadership at Orthopedic Surgery Adult Reconstruction Fellowships. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:2671-2675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cvetanovich GL, Saltzman BM, Chalmers PN, Frank RM, Cole BJ, Bach BR Jr. Research Productivity of Sports Medicine Fellowship Faculty. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4:2325967116679393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Amendola A. Presidential Address of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine: Why AOSSM? Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:3196-3200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Formby PM, Pavey GJ, Van Blarcum GS, Mack AW, Newman MT. An Analysis of Research from Faculty at U.S. Adult Reconstruction Fellowships. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:2376-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Anderson L, Jackson S. Competing loyalties in sports medicine: Threats to medical professionalism in elite, commercial sport. Int Rev Sociol Sport. 2013;48:238-256. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Lemak L. Financial implications of serving as team physician. Clin Sports Med. 2007;26:227-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Micheli LJ, International Federation of Sports Medicine (eds). Team physician manual: International Federation of Sports Medicine (FIMS). 3rd ed. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2012. |

| 27. | Patterson PH, Dyment PG. Being a team physician. Pediatr Ann. 1997;26:13-16, 18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tucker AM. Ethics and the professional team physician. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23:227-241, vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chambers CC, Ihnow SB, Monroe EJ, Suleiman LI. Women in Orthopaedic Surgery: Population Trends in Trainees and Practicing Surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:e116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ence AK, Cope SR, Holliday EB, Somerson JS. Publication Productivity and Experience: Factors Associated with Academic Rank Among Orthopaedic Surgery Faculty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:e41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | O'Reilly OC, Day MA, Cates WT, Baron JE, Glass NA, Westermann RW. Female Team Physician Representation in Professional and Collegiate Athletics. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48:739-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ayers CE. Minorities and the orthopaedic profession. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;58-64. [PubMed] |

| 33. | D'Ambrosia R, Kilpatrick JA. The perception and reality of diversity in orthopedics. Orthopedics. 2004;27:448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Okike K, Utuk ME, White AA. Racial and ethnic diversity in orthopaedic surgery residency programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:e107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Adelani MA, Harrington MA, Montgomery CO. The Distribution of Underrepresented Minorities in U.S. Orthopaedic Surgery Residency Programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:e96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |