INTRODUCTION

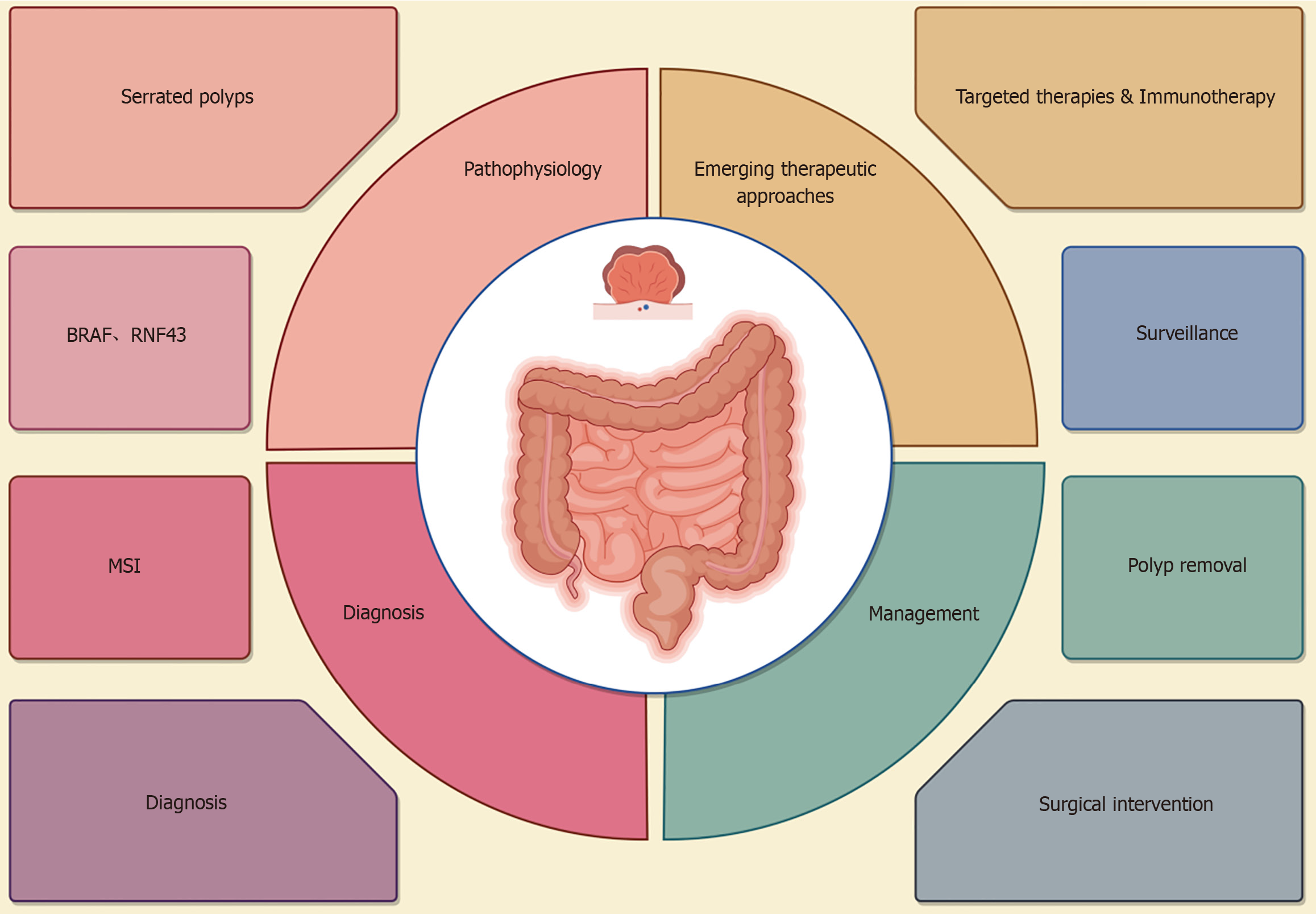

Serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) is a rare disease characterized by the development of multiple serrated polyps in the colon and rectum[1]. The polyps are associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). The prevalence of SPS in the general population is about 0.02% to 0.1%. However, the figures can vary based on the population's demographics, screening practices, and genetic testing availability. SPS may be driven by molecular alterations that promote carcinogenesis[2]. The clinical manifestations of SPS are different, and patients often remain asymptomatic until advanced stages[3]. Colonoscopy is the cornerstone of diagnosis, with histological analysis as the ‘gold standard’. Genetic testing may provide additional insight in some cases such as family history. In clinical practice, SPS can lead to health anxiety due to the possibility that predisposes individuals to cancer. Therefore, comprehensive management is essential for better outcomes. This editorial is aimed to provide an overview of the current understanding of SPS, focusing on its pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic criteria, management approaches, and the psychosocial impact (Figure 1).

Figure 1 An overview of serrated polyposis syndrome from pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management.

MSI: Microsatellite instability.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF SPS

SPS is significantly influenced by mutations in key genetic drivers such as BRAF, CpG island methylation, and microsatellite instability (MSI). These factors contribute to the development of serrated polyps and their progression to colorectal malignancies, which are frequently observed in up to 30% of all CRC cases. BRAF mutation is a key oncogenic driver that promotes tumorigenesis by activating MAPK signaling pathways[4]. In SPS, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays a crucial role, especially in the adenoma-carcinoma progression. These polyps proliferate early through BRAF-mediated MAPK signaling, but as they progress to cancer, the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway becomes essential. Therefore, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway drives CRC development in conjunction with BRAF and other genetic mutations. CpG island methylator phenotype, characterized by widespread hypermethylation of specific tumor suppressor genes, leads to silencing of crucial genes that normally regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis[5]. The MSI in SPS is indicative of defective DNA mismatch repair, which results in a highly mutagenic environment within the genome[6].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF SPS

The common clinical manifestation of SPS is the presence of multiple serrated polyps in the colon, particularly in the proximal colon. These polyps, varying in size with lesions > 1 cm, can be classified into hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated lesions (SSLs), and traditional serrated adenomas. Particularly, SSLs are highly malignant and regarded as CRC precursor[7]. However, many SPS patients are asymptomatic before symptoms of advanced stage occurring such as changes in bowel habits, rectal bleeding, or abdominal discomfort. Early detection and diagnosis are important[8].

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA OF SPS

The diagnosis of SPS is according to clinical and histological criteria, relying on the number, size, and location of serrated polyps[9]. The diagnostic criteria was updated by World Health Organization in 2019 as: (1) 5 or more serrated polyps proximal to the rectum with at least 2 of them ≥ 10 mm; or (2) 20 or more serrated polyps of any size with at least 5 Located proximal to the rectum[10]. Compared to the previous 2010 guidelines, the updated 2019 diagnostic criteria focus more on the number and size of polyps, removing previous stipulations regarding family history or a high number of polyps in other locations[11]. The refinement allows for more standardized and reproducible diagnosis across different clinical circumstances[12].

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES OF SPS

Management of SPS includes endoscopic detection and resection, surveillance and risk stratification[13]. Early detection and resection of serrated polyps are crucial in reducing the CRC risk, with the help of endoscopic techniques, such as high-definition colonoscopy, chromoendoscopy, and narrow-band imaging[14]. Cold snare polypectomy is most commonly used for resecting large serrated polyps (particularly for ≥ 1 cm), while minimizing the complication risk such as perforation or bleeding[15]. Recent advancements in endoscopic techniques have significantly improved the management of SPS, enhancing both polyp detection and resection. High-definition colonoscopy combined with Narrow-Band Imaging offers superior visualization, improving the detection of serrated lesions that may be missed with standard methods. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and Endoscopic Mucosal Resection provide effective removal of larger or sessile polyps, with ESD allowing for en bloc resection, reducing recurrence. These cutting-edge techniques are vital for comprehensive surveillance and management of SPS, contributing to earlier detection, more precise resection, and better long-term outcomes. The surveillance of SPS is regular colonoscopy for every 1-2 years depending on the polyp burden and associated cancer risk, and patients with SSLs or traditional serrated adenomas should increase frequency[16]. It is also important to stratify patients according to risk factors, such as the presence of family history or the size and number of polyps[17]. Identifying factors that influence tailored surveillance plans would address the existing gaps in the field, paving the way for more personalized and effective treatment.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE FOR SPS

Given the intricate nature of SPS, a comprehensive care model is essential for addressing the multifaceted needs of patients. The traditional, one-dimensional focus on medical treatment must be expanded to include a broader view of the patient's life, encompassing not just their physical health but also their mental, social, and occupational well-being. A multidisciplinary care team is ideally suited to address these varied needs. This team could include gastroenterologists, who would focus on the surveillance and management of the serrated polyps and the risk of CRC, alongside oncologists, who can offer expertise in cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment options. However, physical health is just one aspect of the condition. Psychologists and social workers are essential to help patients cope with the anxiety, stress, and depression. These mental health professionals can provide counseling, coping strategies, and emotional support, not only for the patients but also for their families, who are often affected by the hereditary nature of the syndrome. Moreover, occupational therapists can play a key role in supporting patients in maintaining their daily functioning, particularly if the emotional or physical toll of SPS begins to interfere with their ability to work or engage in social activities. By helping patients navigate the impact of the disease on their daily life, these therapists can enhance their overall quality of life and facilitate their reintegration into their communities and workplaces. For SPS patients, this means integrating psychological support, social care, and occupational guidance into routine medical management. Such a collaborative and comprehensive approach can help improve not only patient outcomes but also the overall well-being of individuals living with SPS.

PSYCHOSOCIAL IMPACT OF SPS

The potential risk of developing CRC, coupled with the need for regular surveillance and frequent medical check-ups, creates significant psychosocial challenges for individuals with SPS. The heightened awareness of the elevated cancer risk can result in chronic anxiety, fear, and stress, as patients are constantly reminded of the possibility of malignancy. This ongoing worry about the future of their health can lead to feelings of helplessness, a diminished sense of control, and a pervasive fear about what may lie ahead. The anxiety associated with these concerns often leads to depression and social withdrawal, as patients struggle with managing the emotional toll of their condition[18].

In addition, SPS is often associated with a hereditary cancer syndrome, which not only poses a significant challenge for the individual but also for their family members[19]. The genetic nature of the disease means that there is a possibility that family members may also be affected, leading to additional stress and concerns about the health of loved ones. The need for family-wide screening and the potential of future diagnoses can further exacerbate the psychological burden. The emotional weight of dealing with a hereditary condition can negatively affect the patient’s quality of life, leading to a sense of guilt, grief, and uncertainty for both the patient and their family.

Furthermore, the fear of transmitting the syndrome to future generations often complicates reproductive planning. The prospect of passing the condition to children or siblings may result in feelings of guilt or uncertainty regarding parenthood, with some patients choosing to delay or avoid having children altogether. While genetic counseling and genetic testing can help provide clarity and enable informed decision-making, the emotional burden associated with these discussions should not be underestimated[20]. Even with these resources, the weight of the potential impact on the next generation can cause profound psychological distress. Another significant aspect of the psychosocial burden is the challenge patients face when discussing their diagnosis with loved ones[21].

CONCLUSION

SPS is a complex and challenging disease with a significant molecular basis and a heightened risk of CRC. Endoscopic surveillance and polyp removal are key components of its management. Future research into the development of more refined diagnostic and surveillance protocols would help optimize outcomes. Addressing the psychological burdens associated with SPS is essential to improve the overall quality of life for affected individuals and family members.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade C, Grade D

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

P-Reviewer: Long P; Wang LL; Yu X S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao YQ