Published online Oct 24, 2020. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v11.i10.844

Peer-review started: May 4, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Revised: July 31, 2020

Accepted: September 8, 2020

Article in press: September 8, 2020

Published online: October 24, 2020

Processing time: 169 Days and 23.1 Hours

Cholangiocarcinomas are rare and very aggressive tumors. Most patients have advanced-stage or unresectable disease at presentation, and the systemic therapies have limited efficacy. Albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel) is a solvent-free taxane that has been approved for the treatment of some cancers such as breast, non-small cell lung and pancreatic cancer, however it has not been applied to treat cholangiocarcinoma. We have both preclinical and clinical evidence of the efficacy of nab-paclitaxel in cholangiocarcinoma, yet no phase 3 trials have been made.

A 63-year-old man was diagnosed in December 2016 with stage III B intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery was performed, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy treatment with capecitabine and gemcitabine; although, the gemcitabine was suspended due to allergic reaction after two cycles. In April 2019, metastatic cholangiocarcinoma relapse was diagnosed, and a first-line treatment with FOLFOX scheme was started. Eight cycles were administered, producing an initial clinical improvement and decrease in blood tumor marker levels. Radiological and serological progression was noted in September 2019. As a second-line treatment, FOLFIRI was not recommended due to risk of worsening the patient’s tumor-related diarrhea. A combination therapy with gemcitabine was not feasible, as the patient had previously suffered from an allergic reaction to this treatment. We decided to use nab-paclitaxel as a second-line treatment, and four cycles were administered. Both clinical and serological responses were observed, and a radiological mixed response was also noted.

Advanced cholangiocarcinoma could be treated with nab-paclitaxel monotherapy, which should be studied in combination with other types of treatment (chemotherapy, fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitors).

Core Tip: Cholangiocarcinomas are very aggressive tumors. Most patients have advanced-stage disease at presentation and the efficacy of systemic therapies for this setting is limited. Albumin bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel) has been approved in some cancers but not in cholangiocarcinoma. We present a clinical case of metastatic cholangiocarcinoma treatment with second-line nab-paclitaxel and we review the preclinical and clinical evidence about its useful in these tumors.

- Citation: Martin Huertas R, Fuentes-Mateos R, Serrano Domingo JJ, Corral de la Fuente E, Rodríguez-Garrote M. Albumin-bound paclitaxel as new treatment for metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Oncol 2020; 11(10): 844-853

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v11/i10/844.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v11.i10.844

Cholangiocarcinoma (CC) is a tumor that arises from epithelial bile duct cells. Intrahepatic CC originates above second-order bile ducts, whereas the cystic duct is the anatomical point of distinction between perihilar and distal (extrahepatic) CC[1].

This tumor type accounts for less than 3% of all gastrointestinal cancers[2]. Considering its location, intrahepatic disease is less frequent (between 10%-20% of cases), whereas distal disease is more common (40% of total cases) and perihilar disease is most common (50% of cases)[3]. However, the international classification (i.e., the ICD) of CC does not distinguish between perihilar and distal CC[4]. Also, the American Cancer Society groups intrahepatic bile duct cancers together with primary liver cancers, while placing extrahepatic biliary cancers in a separate category that includes gallbladder cancer. Thus, incidence data on CC subtypes according to location are difficult to interpret[5].

The incidence of intrahepatic CC is rising in the United States and Europe[6-8], although the proportion of early stage or smaller size lesions remains low without an observed increase[7]. The increasing incidence of intrahepatic CC may be due to new diagnostic methods for obstructive jaundice, or may be related to a concomitant increase in certain risk factors (cirrhosis, alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis C virus infection). Extrahepatic CC incidence is declining, and some of these differences may be due to changes in the ICD[9].

CCs are aggressive tumors, and only a minority of patients (approximately 35%) have early-stage disease that is amenable to surgical resection with curative intent. Most patients have advanced-stage disease at presentation[10], and the available systemic therapies for these patients have demonstrated limited efficacy; the median overall survival time with the current standard-of-care first-line chemotherapy (cisplatin and gemcitabine) is less than 1 year[11]. The development of new therapies is therefore essential.

Albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel), a solvent-free taxane, has been demonstrated to produce higher response rates and improved tolerability than solvent-based formulations in patients with advanced metastatic breast cancer or non-small-cell lung cancer, among others tumor types. Additionally, it has not yet been proven to be efficacious in CC-based phase 3 clinical trials[12].

In this study, we present what is, to our knowledge, one of the first published cases in the literature on the use of nab-paclitaxel as treatment for metastatic CC. We demonstrate that this therapy achieves a significant clinical and serological response, and we thus encourage studying this drug as a new treatment option for patients with poor CC prognoses.

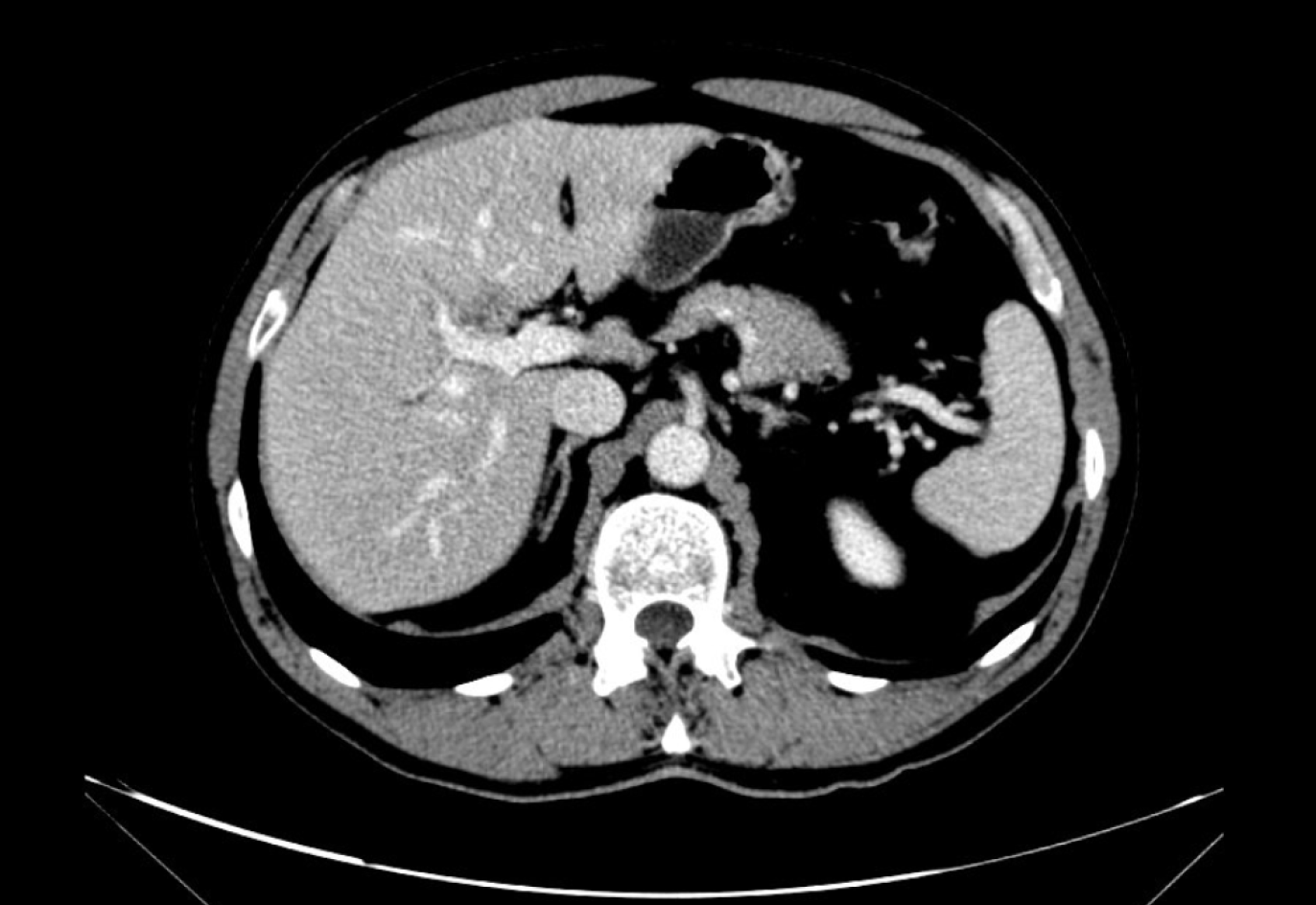

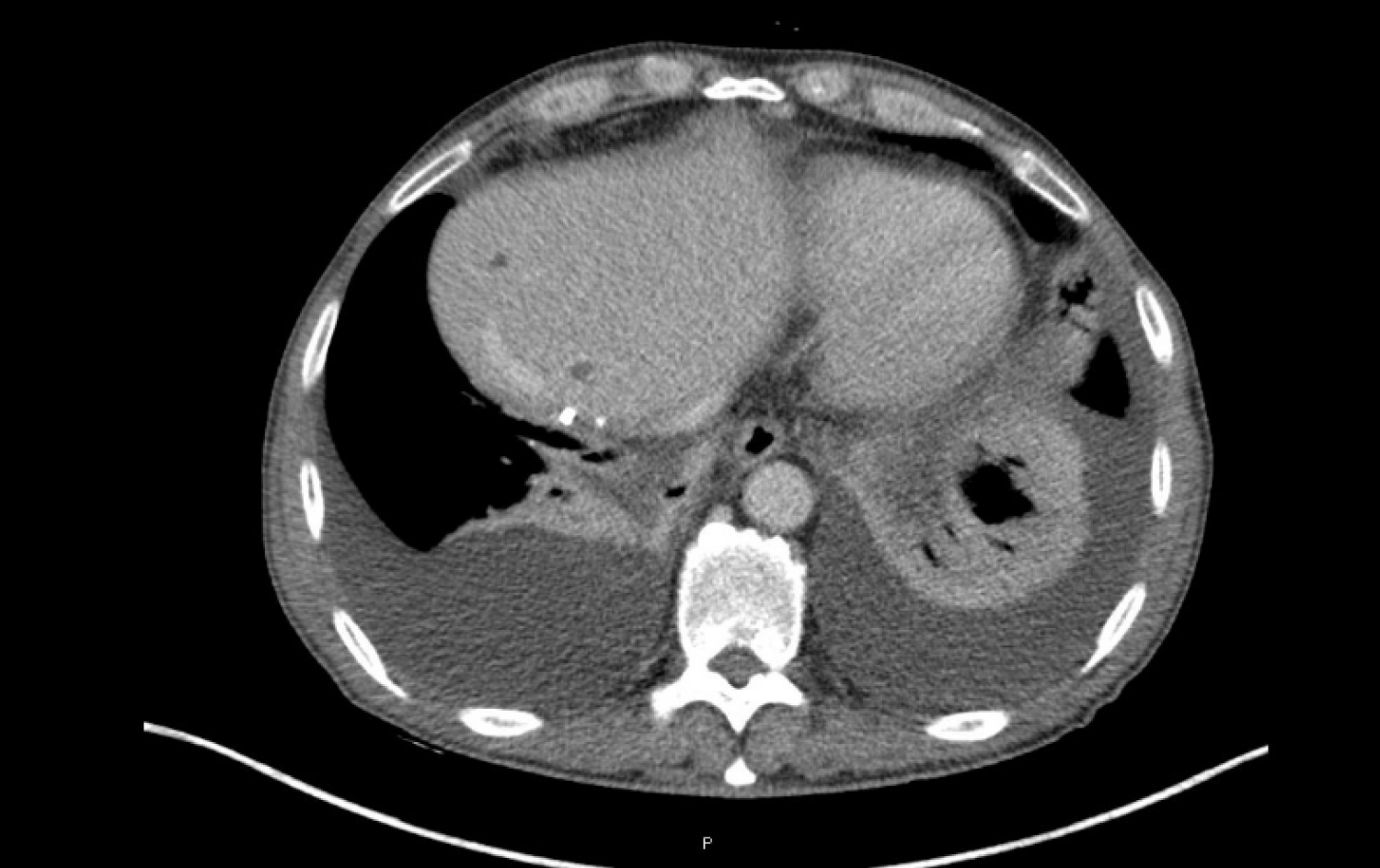

In December 2016, a 63-year-old male underwent a magnetic resonance cholangiography as an assessment for cholecystectomy surgery. A possible cholangiocarcinoma was reported, appearing as a 20 mm hypodense intrahepatic mass at the right liver lobe. Confluence of the hepatic ducts was observed (Figure 1).

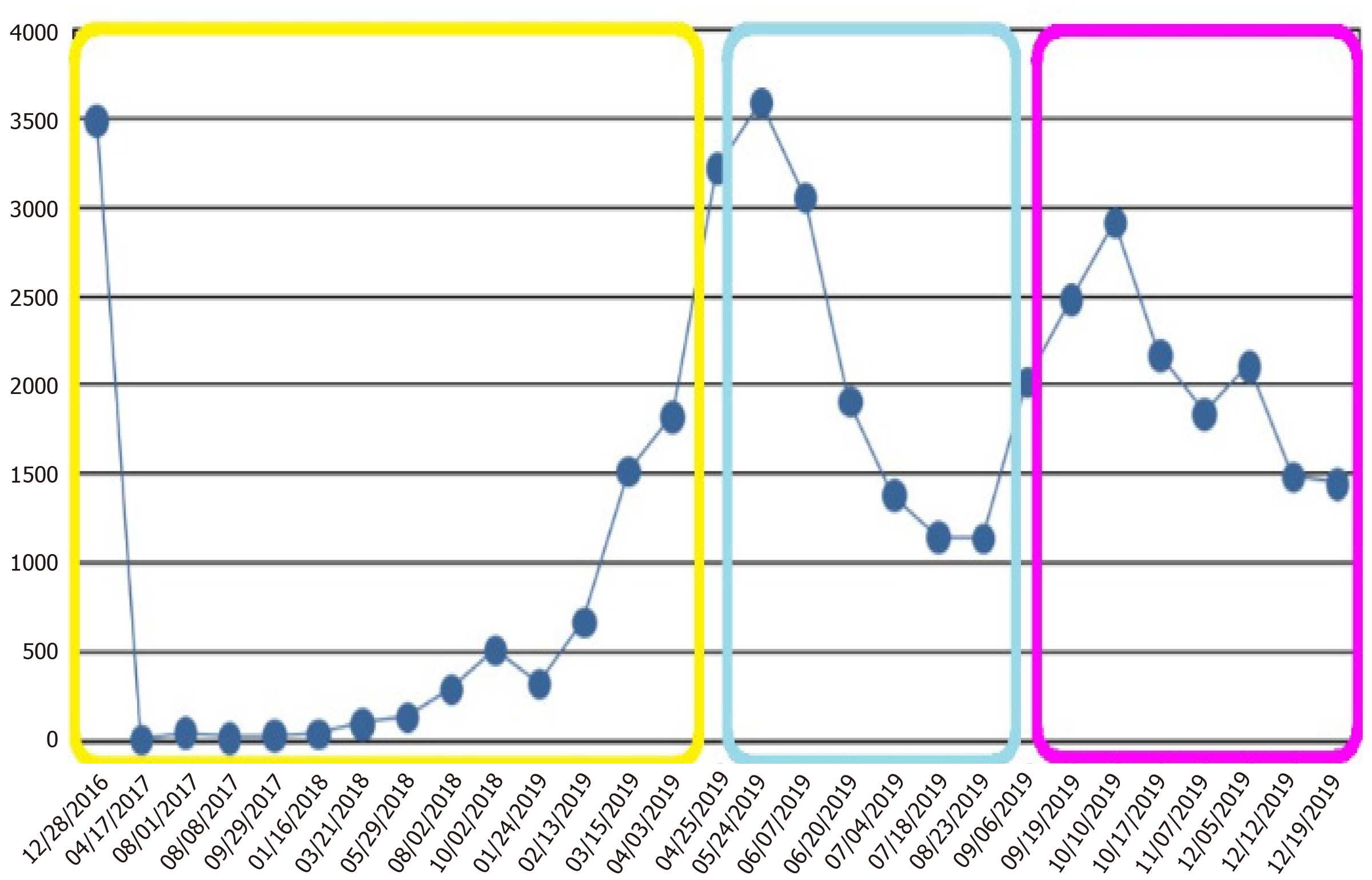

In August 2018, a significant elevation of CA19-9 (294.4 IU/mL, Figure 2) was reported, although no relapse was observed in the computed tomography (CT) scan. The patient was asymptomatic, and the liver blood test results were similar to those presented after surgery [aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 56 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 97 U/L, gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) 455 U/L, alkaline phosphatase (FA) 187 U/L]. Close monitoring was implemented.

In September 2018, CA19-9 continued to increase (513.2 IU/mL, Figure 2). However, the CT scan did not reveal disease relapse. In January 2019, the patient was admitted for cholangitis. A magnetic resonance cholangiography was performed, and no changes were observed in the liver. After discharge in February 2019, close follow-up was continued.

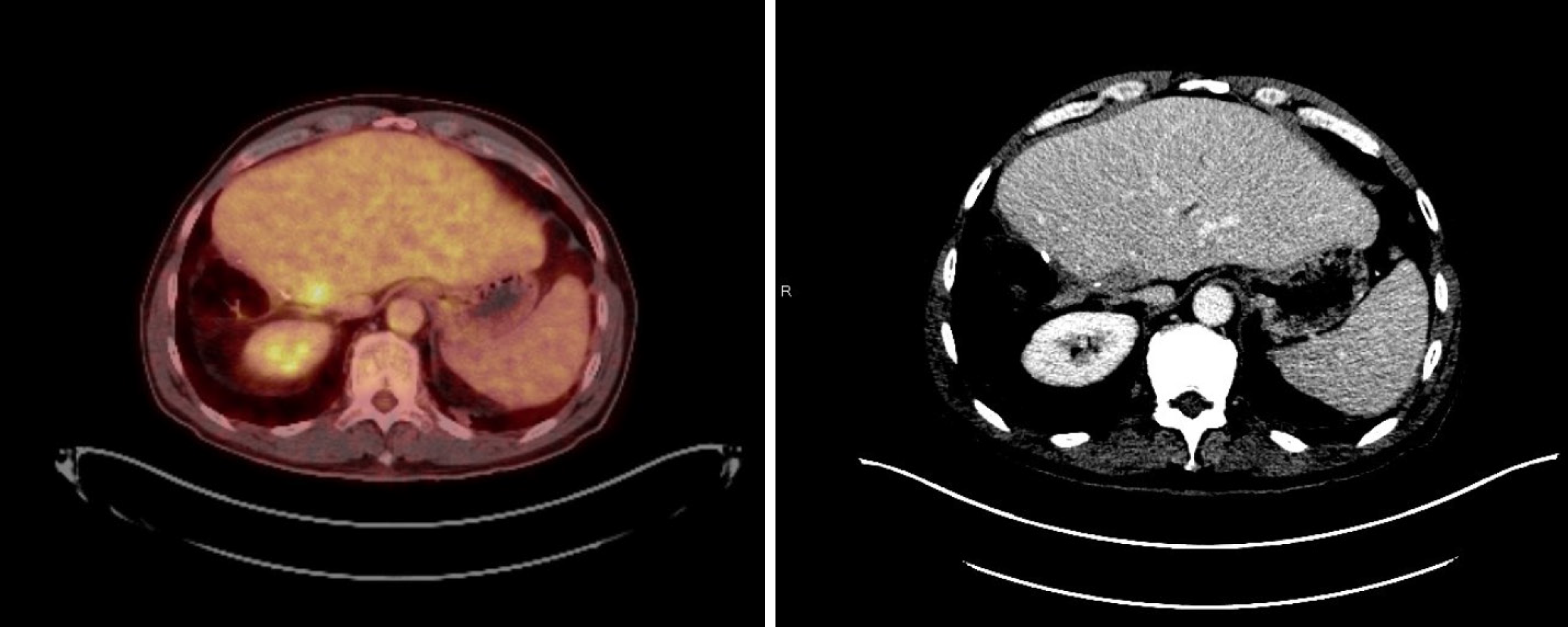

During the following months, the patient experienced clinical deterioration, which included stomach-ache, dyspepsia, and loss of 4 kg of weight. A slight deterioration in the liver blood test was seen (AST 83 U/L, ALT 125 U/L, GGT 1580 U/L, FA 308 U/L) and a progressive rise in CA19-9 was also observed (from 671.3 IU/mL in February 2019 to 3220.9 IU/mL at the end of April 2019, Figure 2). A thorax-abdomen-pelvis computerized tomography (TAP-CT) scan was requested, and no disease relapse was observed. Given the high suspicion of relapse, a positron emission tomography-CT was performed in April 2019. Multiple supraclavicular, mediastinal, and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathies, as well as segment IVa liver nodes and increased soft tissue in the celiac trunk region; all showed increased metabolic activity (Figure 3).

After 25 mo without signs of radiological disease, a relapse of stage IV intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma was diagnosed. We recommended that the patient begin a first-line chemotherapy with cisplatin and gemcitabine at the usual doses. However, since a poor tolerance to gemcitabine was previously presented, we decided to instead begin with the FOLFOX6 treatment scheme.

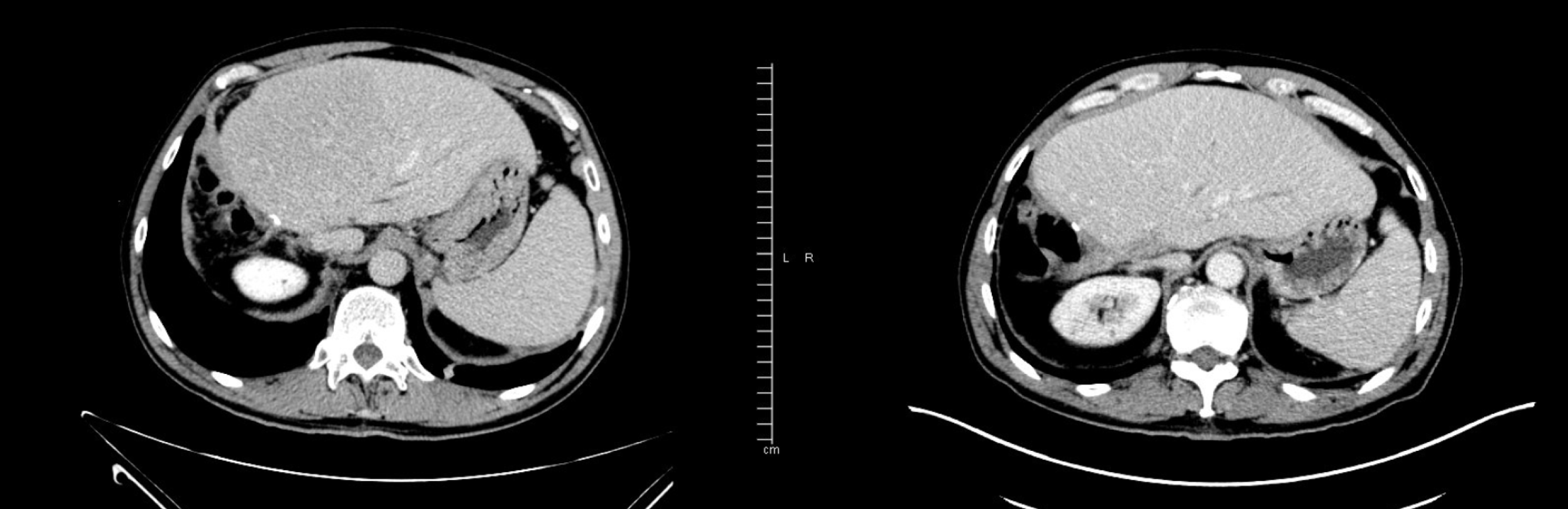

The FOLFOX6 treatment began in April 2019. Initial clinical improvement in cancer-related asthenia was observed, as well as a significant decrease in CA19-9 blood levels (from 3592 IU/mL in May 2019, after two cycles of FOLFOX, to 1138.8 IU/mL in August 2019, after eight cycles of FOLFOX, Figure 2). Grade 1 neurotoxicity and grade 1 rectal bleeding from hemorrhoids were the principal clinical chemotherapy-related toxicities that occurred. After cycle 4, grade 1 thrombopenia was presented, and cycles 5, 6, and 7 were scheduled without a 5-fluorouracil bolus. Grade 2 thrombopenia was then observed, and the administration of cycle 8 was delayed for 1 wk. In July 2019, CT scans were performed (prior to cycle 8) and segment IV liver nodes were not identified, as reported in the previous study (Figure 4). However, a small amount of free fluid in the pelvis, as well as a thickening of the peritoneal leaves, appeared. A mixed response was also considered. Given the improving clinical status of the patient, the same treatment was continued, and cycle 8 was administered with a 10% decrease in oxaliplatin dose.

The patient was referred to our center for surgical evaluation. A TAP-CT scan and blood tests were performed. Distant metastases were not observed, and CA19-9 tumor markers were found to be elevated (3494 IU/mL, Figure 2).

In March 2017, after a right portal embolization was performed that caused compensatory hypertrophy in the left liver lobe, the patient underwent surgery. A hilar tumor with right portal involvement was found. Resection of the extrahepatic bile duct with right trisegmentectomy extended to segment 1 and portal resection were both performed.

The pathology report revealed a moderately differentiated intrahepatic hilar cholangiocarcinoma infiltrating the liver parenchyma, perihilar adipose tissue, cystic duct, and gallbladder neck. Frequent perineural infiltration and vascular invasion were also observed. The tumor had metastasized in one of the four lymph nodes that were isolated from the hilum, which affected the resection margin of the surgical piece.

Stage III B (pT3N1M0) intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, a R1 resection, was diagnosed and the patient was referred to the Medical Oncology Department. Adjuvant chemotherapy treatment with capecitabine 1660 mg/m2 on days 1 to 21 and gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15 every 28 d, given for six cycles, was started. The patient received this treatment between May and November 2017. However, gemcitabine was suspended in July 2017 due to an allergic reaction. After completion of the adjuvant treatment, the follow-up period began.

Despite initial clinical improvement, a progressive clinical deterioration was then presented, with an increase in asthenia. Grade 2 diarrhea (Table 1) and minimal effort dyspnea also appeared. Abdominal examination was normal, and hypoventilation in the right lower lung lobe was auscultated. Cycle 9 was not prescribed, due to grade 1 thrombopenia and persistent grade 2 neutropenia.

| Diarrhea lab work | |

| Hormonal and enzymatic study | Normal range |

| Thyrotropin, TSH | 0.888 µIU/mL |

| Free T4 | 1.10 ng/dL |

| Free T3 | 2.57 pg/mL |

| Serum cortisol | 16.50 µg/dL |

| ACTH | 34.38 pg/mL |

| Pancreatic elastase E1 | More than 437 µg/g of dry stool |

| Microbiology study | No pathogenic microorganisms identified |

| Stool culture | Usual bacterial flora in the sample |

| Clostridium difficile toxin/glutamate dehydrogenase | Negative |

| Autoimmunity study | Negative for celiac disease |

| Anti-transglutaminase immunoglobulin-A antibodies | 3.63 UA/mL |

Serological progression was observed: CA19-9 blood levels rose to 2023 IU/mL (with a previous rise in August 2019 of 1138.8 IU/mL, Figure 2) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) blood levels also rose to 5 IU/mL (high CEA levels had not previously occurred). Regarding liver blood testing, AST levels were 74 U/L, ALT levels were 70 U/L, GGT levels were 849 U/L, and FA levels were 440 U/L. The remaining biochemistry parameters were normal, with the exception of grade 1 hypoalbuminemia.

Given the suspicion of disease progression, a new CT scan was performed in early September 2019. Both peritoneal carcinomatosis (Figure 5) and pleural involvement were confirmed by one last cytological study (Table 2).

| Pleural effusion study | |

| Pleural effusion biochemistry | |

| Glucose | 92 mg/dL |

| Total proteins | 4.1 g/dL |

| Albumin | 2.7 g/dL |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 137 IU/L |

| Cholesterol | 12 mg/dL |

| Triglycerides | 182 mg/dL |

| Adenosine deaminase | Not available |

| Pleural effusion hemogram | |

| Hemoglobin | 0.2 g/dL |

| Platelets | 2600/µL |

| White blood cells | 850/µL |

| Neutrophils | 0 |

| Lymphocytes | 800/µL |

| Blood test biochemistry | |

| Glucose | 86 mg/dL |

| Total proteins | 6 g/dL |

| Albumin | 3.5 g/dL |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 208 IU/L |

| Cholesterol | 195 mg/dL |

| Triglycerides | 122 mg/dL |

| Microbiology study | No pathogenic microorganisms identified |

| Light’s criteria | The pleural effusion meets two of three of Light’s criteria for exudate, and is compatible with cancer |

| Ratio pleural/serum proteins | 0.68 (> 0.5) |

| Ratio pleural/serum proteins | 0.65 (> 0.6) |

| Pleural effusion lactate dehydrogenase > 2/3 upper limit of normal | No |

Massive genetic analysis of the tumor using next-generation sequencing (NGS) was requested. Several alterations could be identified in some genes, such as RNF43, PTCH1, ATM and ARID1A, as well as in variants of unknown significance. Microsatellite instability was not found. Given the clinical deterioration, we decided to begin chemotherapy prior to obtaining these test results.

Massive genetic analysis of the tumor using NGS was requested. Several alterations could be identified in some genes, such as RNF43, PTCH1, ATM and ARID1A, as well as in variants of unknown significance. Microsatellite instability was not found. Given the clinical deterioration, we decided to begin chemotherapy prior to obtaining these test results.

Stage IV cholangiocarcinoma with peritoneal and pleural progression to FOLFOX is presented. There are limited therapeutic options available. We decided to use nab-paclitaxel in the place of other options for specific reasons. On the one hand, we did not recommend that the patient receive FOLFIRI because of the potential risk of worsening his diarrhea. On the other hand, a combination treatment with gemcitabine was not feasible due to his previous allergic reaction to gemcitabine.

Second-line treatment with nab-paclitaxel at the same doses as used for pancreatic cancer (125 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15 every 28 d) was started, although without the associated gemcitabine.

On cycle 1 day 8, grade 3 neutropenia (910 neutrophils/mL) and grade 1 thrombopenia (97500 platelets/mL) were observed, and so the treatment with a reduction of one dose level (100 mg/m2) was prescribed. On cycle 1 day 15, platelets had recovered (150000 platelets/mL) but neutrophils had declined (630 neutrophils/mL). We decided to prescribe a treatment with the same dose level (100 mg/m2), however we also prescribed two injected doses of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF).

On cycle 2 day 1, the patient reported clinical improvements with less asthenia, a 1 kg increase in weight, diarrheal improvements, and slight dyspnea improvements. CA19-9 blood levels rose to 2917.6 IU/mL (CA19-9 levels prior to the start of nab-paclitaxel were 2023.1 IU/mL, Figure 2), and neutrophil and platelet levels were normal. Given the clinical improvements observed, we decided to continue the treatment. Cycle 2 days 1, 8 and 15 at 100 mg/m2, without GCSF, were scheduled.

Four cycles of nab-paclitaxel at 100 mg/m2 doses were administered (except for cycle 1 day 1). GCSF treatment was not needed (except cycle 1 day 15). Neutropenia below 1500 neutrophils/mL and thrombopenia below 10000 platelets/mL were not detected by blood tests prior to cycles 2, 3 and 4, so the hematological tolerance was considered to be excellent (Figure 6).

This clinical case is one of the first published concerning cholangiocarcinoma treatment using nab-paclitaxel monotherapy. Nab-paclitaxel has only been approved as a monotherapy for breast cancer[13,14]. In addition, it has proven to be useful when scheduled weekly[15,16]. In the remaining settings, a combination with other drugs (gemcitabine, carboplatin) was always required.

The only data on the efficacy of nab-paclitaxel in metastatic cholangiocarcinoma was phase 2 clinical trials but was part of a combination treatment in this case[17,18]. In addition, a retrospective registry of cases[19] and preclinical studies have also been performed[20,21]. However, no prospective evidence from phase 3 clinical trials has been found.

A combination of nab-paclitaxel with gemcitabine, as used in pancreatic cancer, is potentially more effective in cholangiocarcinoma in terms of disease control than nab-paclitaxel alone. In the phase 2 trials of first-line nab-paclitaxel combinations, the disease control rate is higher than 50% and ranges from 66% (in combination with gemcitabine)[17] to 84% (in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin)[18]. However, our patient received nab-paclitaxel as a monotherapy and second-line treatment after platinum-containing chemotherapy, which can explain the reduced efficacy of nab-paclitaxel in this context. We decided to use weekly nab-paclitaxel based on data from the combination of weekly nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine regimens for pancreatic cancer, and also from data showing the efficacy of weekly nab-paclitaxel monotherapy for breast cancer.

Achievement of a clinical and serological response was shown by a decrease in CA19-9 as well as improved liver function tests. There was also a mixed radiological response observed after four cycles of nab-paclitaxel. Therefore, we can consider that, although a new lesion appeared, the disease is controlled due to the shrinking or stabilization of most lesions. In a highly aggressive disease such as cholangiocarcinoma, a clinical response can be considered to be a clinical benefit and, therefore, a justification to continue treatment, despite the fact that a strict radiological response was not achieved. The objective of treatment for this patient was improving his quality of life, which was observed. Therefore, while we have evidence of the biological activity of nab-paclitaxel in cholangiocarcinoma, a partial radiological response was not observed.

We also have preclinical evidence of the efficacy of nab-paclitaxel in cholangiocarcinoma. In one study[20], primary cultures prepared from human mixed and mucin intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma specimens were evaluated for cell proliferation and apoptosis after incubation with increasing concentrations of different drugs. Nab-paclitaxel showed an inhibitory effect on cell proliferation in both mixed- and mucin intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma primary cultures. Additionally, nab-paclitaxel induced a significant increase in apoptotic activity in only mucin-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. In another study[21], the inhibitory effect of paclitaxel and nab-paclitaxel in different cholangiocarcinoma cell lines was studied, revealing that both drugs induced anti-proliferative effects. Furthermore, a toxin-induced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma rat model was used to evaluate the in vivo tumor activity of paclitaxel, nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin regimen. Only nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin induced antitumor effect in the rat model. Compared with paclitaxel, nab-paclitaxel demonstrated increased effectiveness in reducing in vivo tumor formation by disrupting the desmoplastic stroma.

The genomic alterations identified in our patient’s tumor by NGS do not appear to be related to nab-paclitaxel efficacy. In addition, we have no molecular markers that predict nab-paclitaxel activity in metastatic cholangiocarcinoma, as we do for other tumor types.

In a study evaluating the response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the GeparSepto trial according to the genomic alterations revealed by NGS, there was an increased response to nab-paclitaxel that was only observed in PIK3CA wild-type breast cancer patients[22]. The presence or absence of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) amplifications, a pathway that is aberrantly activated in 15%-20% of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas[23], was not related to the nab-paclitaxel response in this study. In non-small cell lung cancer, nintedanib is the only approved agent that targets the FGFR axis. This agent is limited to adenocarcinoma and is used in combination with docetaxel, according to the results of LUME-Lung 1 trial[24]. Based on this trial, a combination of a taxane, such as nab-paclitaxel, and an FGFR inhibitor in patients with FGFR amplifications would be a viable option for future use in metastatic cholangiocarcinoma patients.

Nab-paclitaxel monotherapy could be a viable treatment option for patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma in later lines of treatment, after they have already progressed to standard therapies. This therapy has demonstrated preliminary efficacy in preclinical models. In addition, according to phase 2 clinical trial results, nab-paclitaxel is a potential first-line treatment in combination with either gemcitabine or gemcitabine plus cisplatin. Nab-paclitaxel should be studied as a potential treatment for metastatic cholangiocarcinoma in combination with not only chemotherapy but also with FGFR inhibitors. This is based on available efficacy data for a combination of taxane and FGFR inhibitor that has been used in other cancers. This approach could therefore be an interesting alternative to be explored over the next years.

The authors thank the patient and his family for their collaboration.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Donadon M, Fu TL, Perini M S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Rizvi S, Gores GJ. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1215-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 923] [Cited by in RCA: 966] [Article Influence: 80.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vauthey JN, Blumgart LH. Recent advances in the management of cholangiocarcinomas. Semin Liver Dis. 1994;14:109-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Kamangar F, Winter JM, Lillemoe KD, Choti MA, Yeo CJ, Schulick RD. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2007;245:755-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 882] [Cited by in RCA: 1017] [Article Influence: 56.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463-473; discussion 473-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 897] [Cited by in RCA: 865] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | American Cancer Society. Cancer Statics Center. 2020. Available from: https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org. |

| 6. | Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 773] [Cited by in RCA: 797] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shaib YH, Davila JA, McGlynn K, El-Serag HB. Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase? J Hepatol. 2004;40:472-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 543] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Patel T. Worldwide trends in mortality from biliary tract malignancies. BMC Cancer. 2002;2:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Welzel TM, McGlynn KA, Hsing AW, O'Brien TR, Pfeiffer RM. Impact of classification of hilar cholangiocarcinomas (Klatskin tumors) on the incidence of intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:873-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Gonen M, Burke EC, Bodniewicz BS J, Youssef BA M, Klimstra D, Blumgart LH. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507-517; discussion 517-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 973] [Cited by in RCA: 964] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP, Roughton M, Bridgewater J; ABC-02 Trial Investigators. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2617] [Cited by in RCA: 3165] [Article Influence: 211.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Yardley DA. nab-Paclitaxel mechanisms of action and delivery. J Control Release. 2013;170:365-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, Shaw H, Desai N, Bhar P, Hawkins M, O'Shaughnessy J. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7794-7803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1422] [Cited by in RCA: 1487] [Article Influence: 74.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aigner J, Marmé F, Smetanay K, Schuetz F, Jaeger D, Schneeweiss A. Nab-Paclitaxel monotherapy as a treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer in routine clinical practice. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:3407-3413. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Gradishar WJ, Krasnojon D, Cheporov S, Makhson AN, Manikhas GM, Clawson A, Bhar P. Significantly longer progression-free survival with nab-paclitaxel compared with docetaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3611-3619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gradishar WJ, Krasnojon D, Cheporov S, Makhson AN, Manikhas GM, Clawson A, Bhar P, McGuire JR, Iglesias J. Phase II trial of nab-paclitaxel compared with docetaxel as first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer: final analysis of overall survival. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012;12:313-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sahai V, Catalano PJ, Zalupski MM, Lubner SJ, Menge MR, Nimeiri HS, Munshi HG, Benson AB, O'Dwyer PJ. Nab-Paclitaxel and Gemcitabine as First-line Treatment of Advanced or Metastatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1707-1712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shroff RT, Javle MM, Xiao L, Kaseb AO, Varadhachary GR, Wolff RA, Raghav KPS, Iwasaki M, Masci P, Ramanathan RK, Ahn DH, Bekaii-Saab TS, Borad MJ. Gemcitabine, Cisplatin, and nab-Paclitaxel for the Treatment of Advanced Biliary Tract Cancers: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:824-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Unseld M, Scheithauer W, Weigl R, Kornek G, Stranzl N, Bianconi D, Brunauer G, Steger G, Zielinski CC, Prager GW. Nab-paclitaxel as alternative treatment regimen in advanced cholangiocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:588-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fraveto A, Cardinale V, Bragazzi MC, Giuliante F, De Rose AM, Grazi GL, Napoletano C, Semeraro R, Lustri AM, Costantini D, Nevi L, Di Matteo S, Renzi A, Carpino G, Gaudio E, Alvaro D. Sensitivity of Human Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Subtypes to Chemotherapeutics and Molecular Targeted Agents: A Study on Primary Cell Cultures. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chang PM, Cheng CT, Wu RC, Chung YH, Chiang KC, Yeh TS, Liu CY, Chen MH, Chen MH, Yeh CN. Nab-paclitaxel is effective against intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma via disruption of desmoplastic stroma. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:566-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Loibl S, Treue D, Budczies J, Weber K, Stenzinger A, Schmitt WD, Weichert W, Jank P, Furlanetto J, Klauschen F, Karn T, Pfarr N, von Minckwitz G, Möbs M, Jackisch C, Sers C, Schneeweiss A, Fasching PA, Schem C, Hummel M, van Mackelenbergh M, Nekljudova V, Untch M, Denkert C. Mutational Diversity and Therapy Response in Breast Cancer: A Sequencing Analysis in the Neoadjuvant GeparSepto Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:3986-3995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Krook MA, Lenyo A, Wilberding M, Barker H, Dantuono M, Bailey KM, Chen HZ, Reeser JW, Wing MR, Miya J, Samorodnitsky E, Smith AM, Dao T, Martin DM, Ciombor KK, Hays J, Freud AG, Roychowdhury S. Efficacy of FGFR Inhibitors and Combination Therapies for Acquired Resistance in FGFR2-Fusion Cholangiocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19:847-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tsironis G, Ziogas DC, Kyriazoglou A, Lykka M, Koutsoukos K, Bamias A, Dimopoulos MA. Breakthroughs in the treatment of advanced squamous-cell NSCLC: not the neglected sibling anymore? Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |