Published online Apr 24, 2019. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v10.i4.192

Peer-review started: August 9, 2018

First decision: October 5, 2018

Revised: March 15, 2019

Accepted: April 8, 2019

Article in press: April 9, 2019

Published online: April 24, 2019

Processing time: 258 Days and 10.5 Hours

Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor (DGCT) is an uncommon locally invasive odontogenic neoplasm. It is considered to be a solid variant of calcifying odontogenic cyst (COC). This tumor makes up for only 2%-14% of all COCs and less than 0.5% of all odontogenic tumors which owes to its rarity. The purpose of this paper was to describe a case of DGCT and the treatment adopted in our case, and to provide a review of this case in the indexed literature.

In this article, we discussed a case of 18 year old male who reported with a chief complaint of a recurrent swelling and dull aching pain in upper left back region of the jaw. Computed tomography scan was carried out which revealed hypodense lesion with a few hyperdense flecks within it suggesting the presence of calcification. On incisional biopsy, diagnosis of COC was given. After segmental resection of the lesion, histopathogically odontogenic epithelium was noted along with calcifications, ghost cells and dentinoid material. Special staining was done with van Gieson and it showed pink areas of dentinoid material and yellow colour represented ghost cells. Hence, amalgamation of careful clinical examination, use of advanced radiographic imaging and detailed histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of DGCT. The patient was followed up for one year and there was no recurrence of the lesion or signs of any residual tumor.

Radical treatment should be carried out along with mandatory long-term follow up in order to avoid recurrence in aggressive lesions.

Core tip: There is diversity in the differential diagnosis of a variety of odontogenic cysts and tumors. A detailed case history, use of advanced radiographic imaging techniques and appropriate histopathological examination remains the mainstay for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning of a lesion. Adequate surgical intervention is required for aggressive lesions like dentinogenic ghost cell tumor. Treatment with enucleation might lead to recurrence of this tumor. Hence, patients should be treated with more radical approach and should be kept on long- term follow up.

- Citation: Patankar SR, Khetan P, Choudhari SK, Suryavanshi H. Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor: A case report. World J Clin Oncol 2019; 10(4): 192-200

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v10/i4/192.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v10.i4.192

Cysts and tumors of odontogenic origin are diverse histologically and in their behaviour. Hence their thorough details including clinical, radiographic and histopathological findings should be considered before arriving at a confirmatory diagnosis.

Calcifying odontogenic cyst (COC) was originally described by some researchers in 1962 as a distinct entity[1]. In 1971, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially defined it as a “non-neoplastic cystic lesion in which the epithelial lining shows a well-defined basal layer of columnar cells, an overlaid layer that is often many cells thick that may resemble stellate reticulum and masses of ghost epithelial cells that may be in the epithelial cyst lining or in the fibrous capsule. Dysplastic dentin may be laid down next to the basal cell layer of the epithelium”[2].

Singhaniya et al[3] provided the classification for COCs for better understanding of the variations of the lesion and grouped the COCs into the cystic type termed as “calcifying cystic odontogenic tumour” (CCOT) or Type I and the solid/neoplastic type, termed as “Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor” (DGCT) or Type II. However, according to the classification of odontogenic tumors and cysts given by WHO in 2017, dentinogenic ghost cell tumor has been described under mixed (epithelial-mesenchymal) origin tumors[4].

This article reports a case of an 18-year-old male patient who was diagnosed with DGCT which is a relatively rare entity at such a young age.

An 18-year-old male patient reported with a chief complaint of a recurrent swelling and dull aching pain in upper left back region of the jaw since 1 mo.

Patient was apparently alright 1 mo back until he experienced dull aching pain in upper left posterior region of the jaw.

Patient was otherwise healthy 4 years back until he noticed a swelling in upper left region of jaw which slowly increased to a large size. He visited a hospital at his native place and was operated twice one year apart for the same swelling. The swelling reduced in size but did not disappear completely. So, the patient reported to the Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology with the chief complaint of recurrent swelling and dull pain in upper left region of the jaw. The past medical history of the patient was not contributory.

Not contributory.

Extraoral examination revealed a diffuse swelling of approximately 7 cm × 5 cm in size on the left side of face extending antero-posteriorly from left ala of nose to the anterior border of the ramus and supero-inferiorly from infraorbital rim to the corner of the mouth. Skin over the swelling was normal (Figure 1). On palpation, the swelling was found to be bony hard in consistency. Temperature over the swelling was slightly raised. A single, left submandibular lymph node was palpable approximately 2 cm × 2 cm in size. Intraorally, a single, smooth, ovoid swelling, extending antero-posteriorly from distal of 22 to mesial of 26 and supero-inferiorly from vestibular depth to marginal gingival was noticed (Figure 2). On palpation, it was bony hard and slightly tender with fixity to underlying bone.

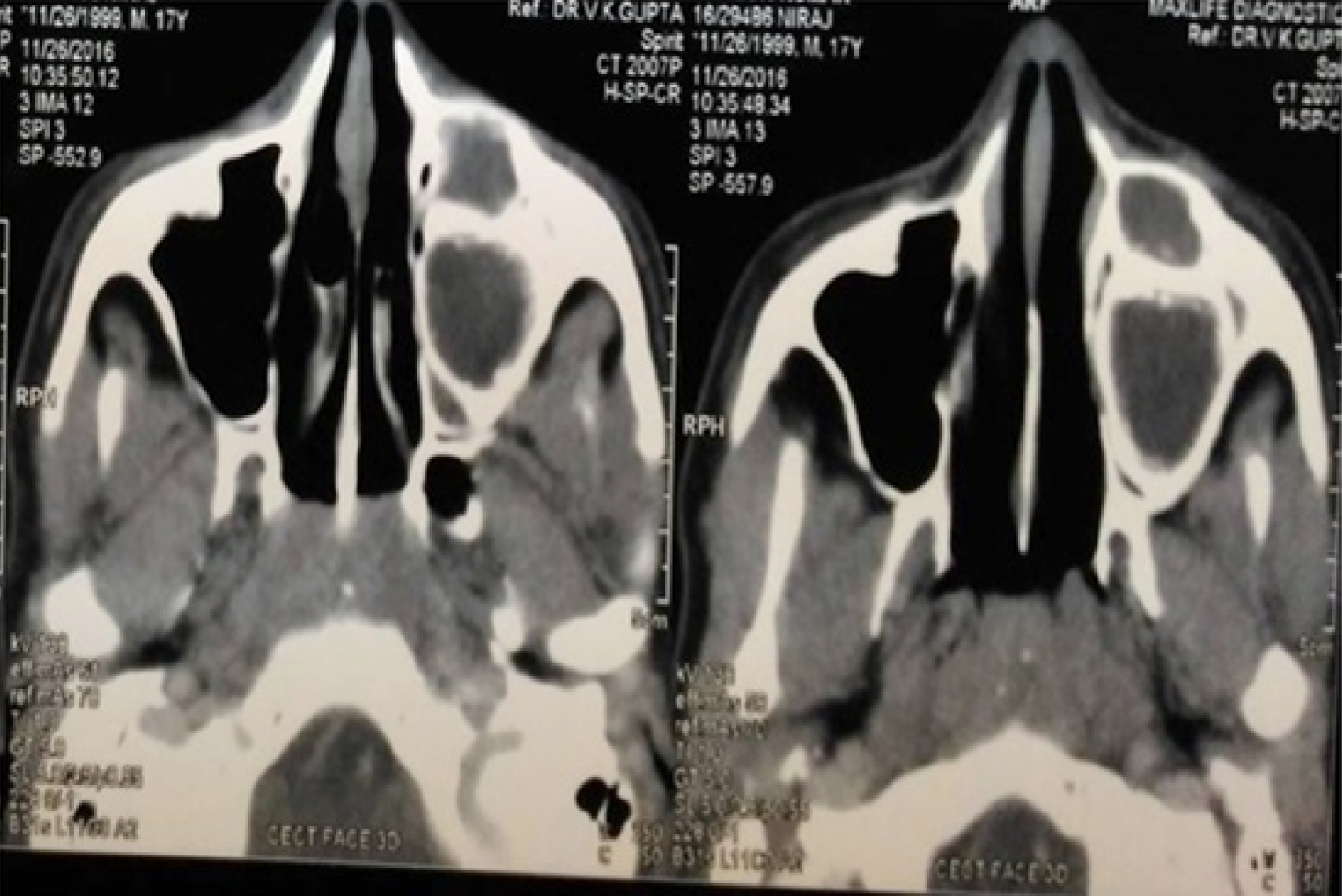

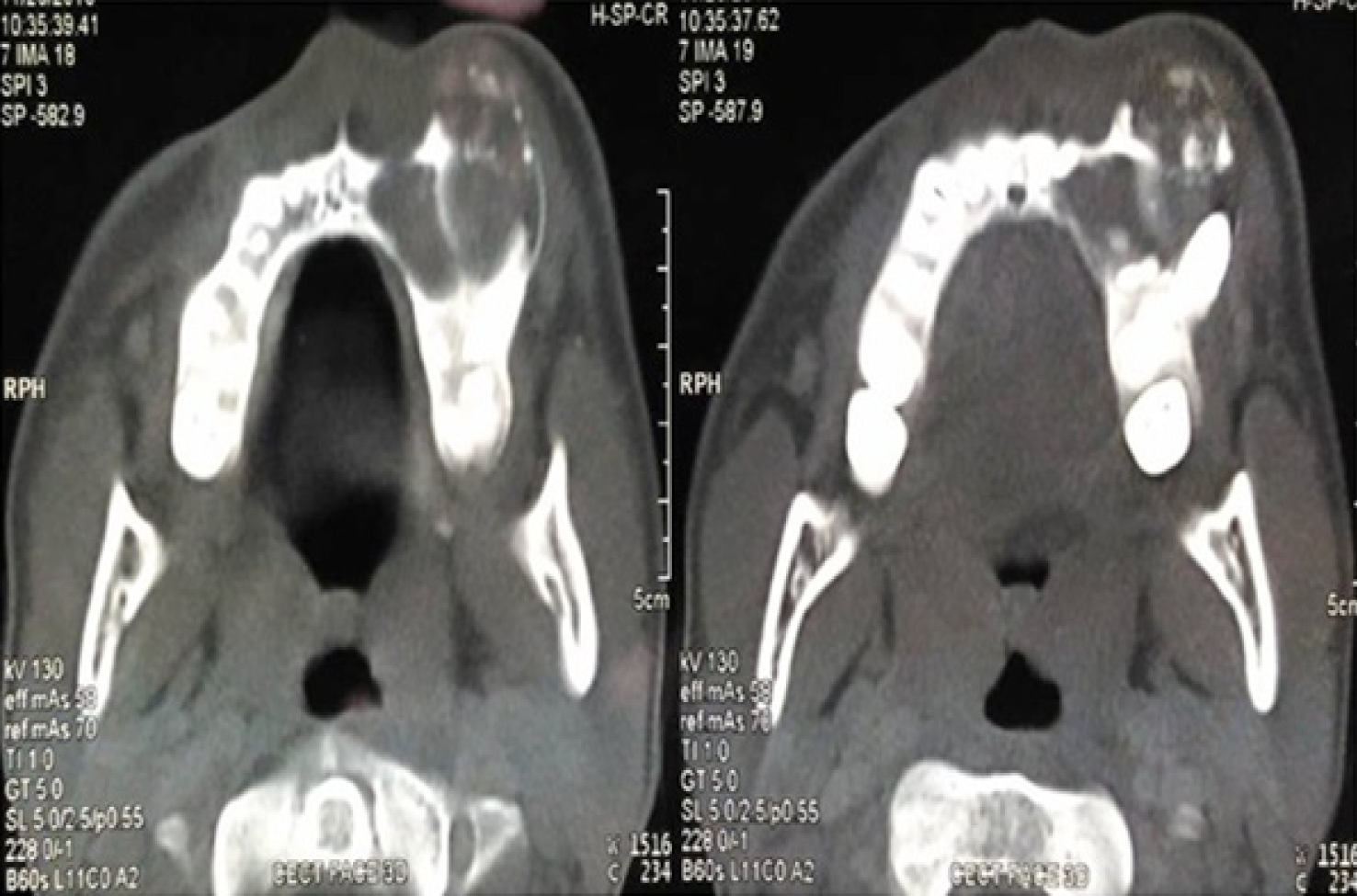

Computed tomography (CT) scan showed a mixed hypodense hyperdense lesion in maxillary left region extending antero-posteriorly from the distal aspect of 21 up to 26 regions and supero-inferiorly from alveolar ridge upto the floor of orbit. The lesion had a well defined, partly corticated periphery (Figure 3). It had predominantly hypodense internal structure with multiple intermittent hyperdense flecks present within. Expansion was evident on the buccal aspects of the alveolus, anterior and lateral walls of the left maxillary sinus with thinning and perforation evident at multiple sites. Thinning of the floor of left orbit with invagination of the lesion was noticed (Figure 4).

Based on the clinical and radiographic findings, provisional diagnosis of benign odontogenic tumor was arrived at. Due to the extent of the lesion and history of recurrence, CCOT was considered.

Following routine blood investigations, patient was referred to the department of oral surgery for incisional biopsy of the lesion.

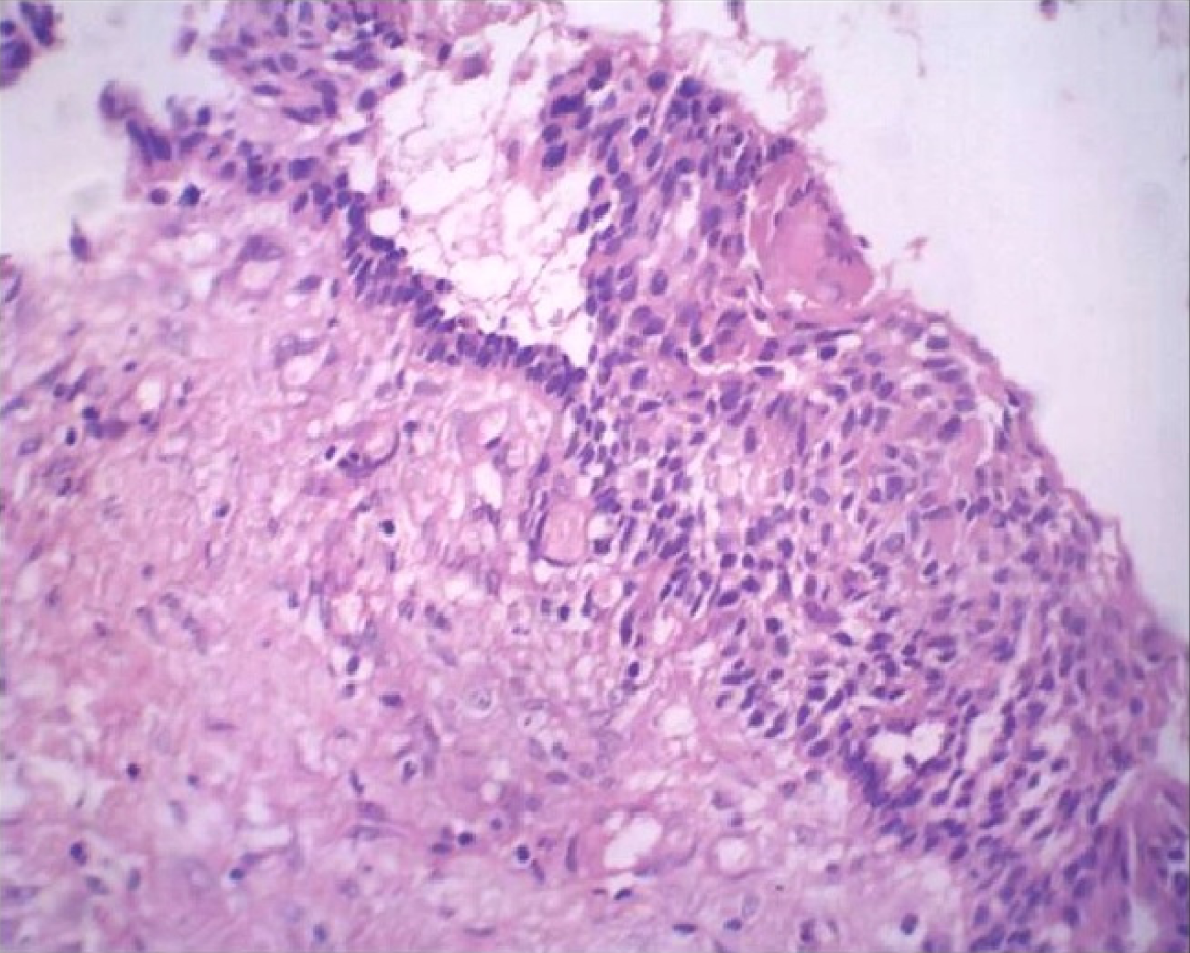

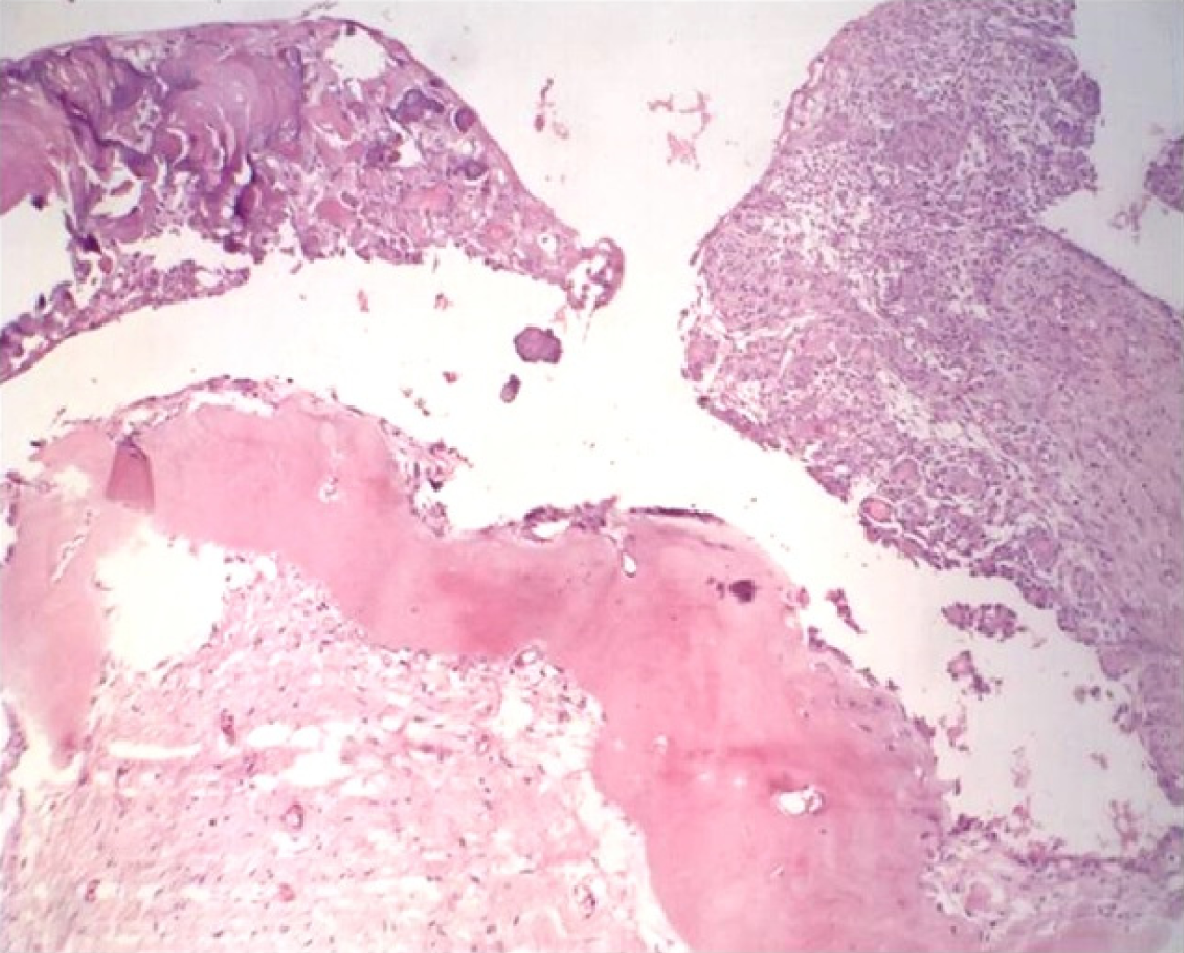

Careful histopathological examination of Hematoxylin and Eosin (H and E) stained sections showed the following features: cystic lumen was lined by odontogenic epithelium of variable thickness. Basal cells of the epithelium were tall columnar with polarized hyperchromatic nuclei. Stellate reticulum like cells could be noted above the basal cells. The superficial layers showed groups of pale eosinophilic ghost cells. The connective tissue wall was predominantly fibrous with dense bundles of collagen fibres and devoid of inflammation (Figure 5). Many active odontogenic rests were also seen in the connective tissue. One or two areas demonstrated globular areas of calcifications.

The histopathological diagnosis of the incised biopsy specimen was given as COC.

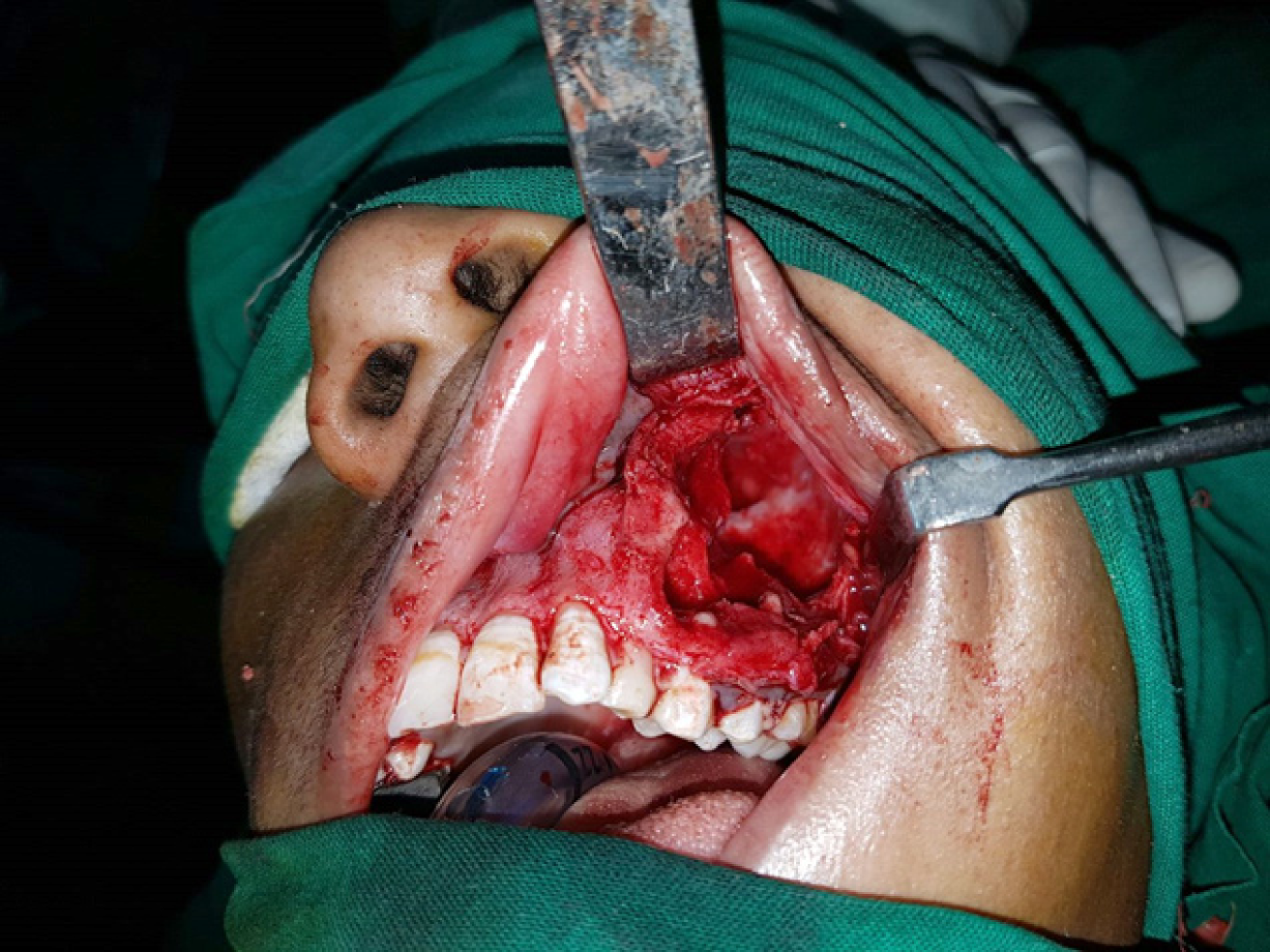

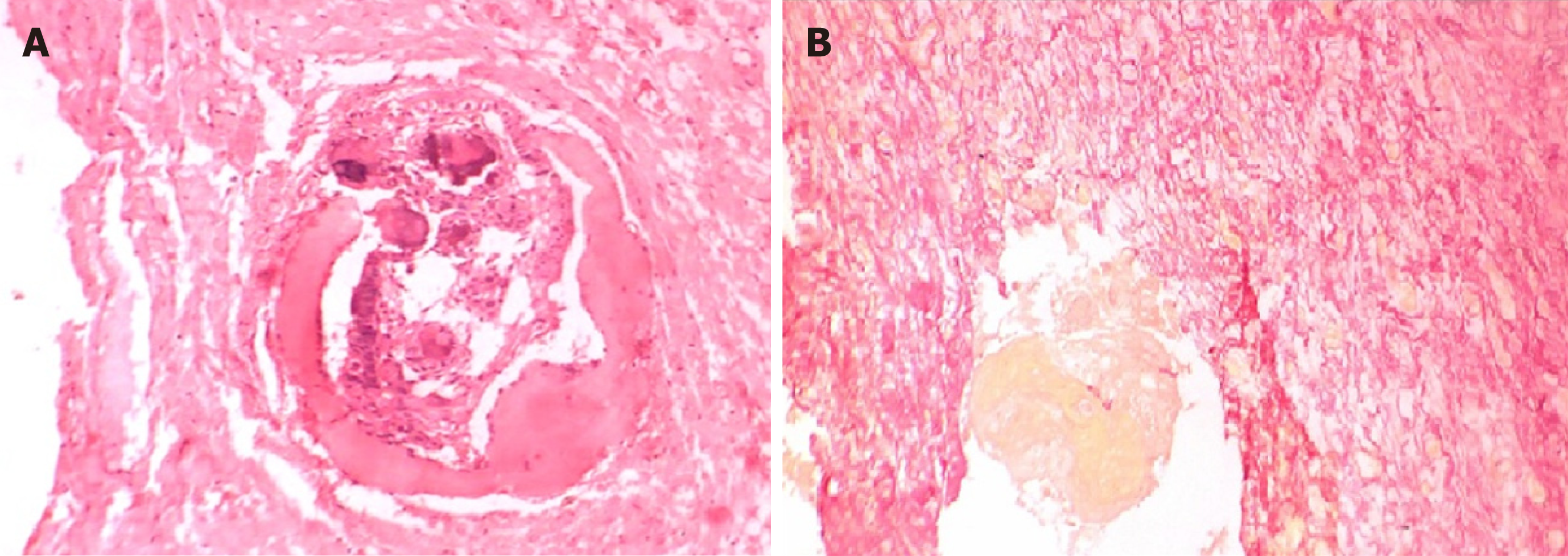

Segmental resection was carried out in this case (Figure 6) and the specimen was subjected to H and E staining. The histopathological examination revealed a connective tissue wall with odontogenic epithelium. At few places, the epithelium was proliferating with stellate reticulum like cells surrounded by spindle shaped cells. Aggregates of eosinophilic ghost cells surrounded by irregular calcifications could be noted towards the lumen. Large areas of dentinoid were conspicuously present in the subjacent connective tissue (Figure 7). At places, active odontogenic rests and metastatic bone was seen.

Special staining with van Gieson’s stain identified dentinoid which stains pinkish red and ghost cells which appear yellow in colour (Figure 8).

Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor.

Segmental resection.

Patient is being followed-up since one year and has not reported with any post-operative complications or recurrence.

From 1962 till date, different terminologies and classifications of COC have been proposed and practiced in the literature.

Fejerskov and Krogh[5] in 1972 suggested the term “calcifying ghost cell odontogenic tumour.” They were of the opinion that the term COC is not entirely appropriate, because there could be the possibility of cystic degeneration taking place in the centre of proliferating epithelial islands rather than epithelial changes developing in a pre-existing cyst wall. The other points raised by them were regarding the presence of the ghost cells which may subsequently show calcification and the proliferative potentiality of some lesions giving rise to lesions of considerable size.

In 1991, Buchner et al[6] clinically classified COCs into central and peripheral lesions. He further sub-classified each of them into cystic or neoplastic variants and also included rare malignant variant of COC in his classification.

Following the dualistic concept, Hong, in 1991, classified COCs into cystic and neoplastic types. He used the term “epithelial odontogenic ghost cell tumor” for the solid variant[7].

In 1998, Toida[8] suggested that the terms “cystic” or “neoplastic” were not appropriate because the former term described the morphology while the later defined the biological behavior of the lesion. The term “cystic” which was considered synonymous for “non-neoplastic” could be misleading as there may be lesions with cystic architecture that have extensive proliferative capacity.

This conundrum was solved by WHO classification in 2005. According to the WHO, the spectrum of odontogenic ghost cell tumours comprises CCOT, DGCT and ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma.

DGCT was defined by WHO in 2005 as, “A locally invasive neoplasm characterized by ameloblastoma-like islands of epithelial cells in a mature connective tissue stroma. Aberrant keratinization may be found in the form of ghost cells in association with varying amounts of dysplastic dentin”[9]. It is characterized by ameloblastomatous odontogenic epithelium, presence of ghost cells and dentinoid material[10].

DGCT is the solid, clinico-pathologic variant of CCOT. It may develop at any age from the second to the eighth decade of life, mean age of occurrence being 50 years with no gender predilection[11]. However, Shah et al[12] found that this lesion occurs more commonly in males than in females.

Intraosseous DGCT has been reported to occur predominantly in canine to first molar region[13]. It may be seen in the edentulous region of the jaws as well. de Arruda et al[14] who reviewed 55 cases of DGCTs, observed that it mostly occurs in fourth decade of life and mandible is the most common site of involvement. The present case was noted in maxilla between lateral incisor and first molar in an 18-year-old male patient, which is at a comparatively younger age than the average age as reported by Candido who found that the age ranges from 41 to 83 years for DGCTs with an average age of 62 years.

The size of the intra-osseous DGCT varies from 1 to more than 10 cm in diameter. The clinical features of intra-osseous DGCT variants include visible swelling, with obvious facial asymmetry due to expansion of the jaw, and with occasional occurrence of obliteration of the maxillary sinus or infiltration of the soft tissues. Swelling can be painful or painless and occasionally accompanied by pus discharge, tooth displacement or mobility[15]. Buchner et al[16] studied 45 cases and found that the lesion presents with dull, slight or mild pain in 52% of the cases. The reported case presented with a diffuse extraoral bony hard swelling of 7 cm × 5 cm size which was uniform throughout.

Amounting to the presence and extent of calcification, DGCT may appear radiographically as radiolucent, radiopaque or mixed lesion. Lesions can be unilocular or multilocular with either welldefined or ill-demarcated margins[17]. These findings were in accordance with the literature review carried out by Konstantakis et al[15] in 2013. Presence of impacted teeth and displacement and/or root resorption of adjacent teeth have also been reported[9]. This case was a mixed hypodense-hyperdense unilocular lesion with ill defined borders. Thinning and perforation of maxillary sinus walls suggested the aggressive nature of the tumour.

Histopathologically DGCT is characterized by sheets and rounded islands of odontogenic epithelial cells seen in a mature connective tissue stroma[14]. A characteristic feature of DGCT is ghost cells. The ghost cells are described as swollen, ellipsoidal keratinized epithelial cells characterized by the loss of nuclei, preservation of basic cellular outlines, induction of foreign body granuloma and potential to calcify. There are different theories of origin of Ghost cells such as the transformation of epithelial cells, metaplastic transformation of odontogenic epithelium, and squamous metaplasia with secondary calcification due to ischemia, degeneration of epithelial cells or as a result of apoptotic process. The presence of ghost cells alone is not pathognomic of DGCT, since they can also be identified in other neoplasms such as odontomas, ameloblastomas and ameloblastic fibroodontomas. The latter tumor can be eliminated from the histopathological differential diagnosis by the presence of a cellular primitive ectomesenchyme resembling dental papilla. The ghost cells may be demonstrated using special stains such as van Gieson, Goldner, or Ayoub-Shklar histochemical stains. This is particularly helpful in confirming the histopathological diagnosis of the solid lesions in which there is an abundance of dentinoid and the ghost cells are less conspicuous[9].

The other characteristic histopathological feature of DGCT is formation of dentinoid or osteoid material, found in connection with ghost cells. The rationale for the formation of dentinoid material has been documented in literature. Gorlin and his colleagues considered it to represent an inflammatory response of the body tissue toward masses of ghost cells. Abrams and Howell further stated that the masses of “ghost cells” induce granulation tissue to lay down juxtraepithelial osteoid which may calcify. On the other hand, Sauk hypothesized that it might be an inductive phenomenon. Singhaniya et al[3] were of the opinion that dentinoid stands for a metaplastic change in the connective tissue without the participation of granulation tissue. Bafna et al[9] considered a mesodermal origin for dentinoid based on the finding that it is usually not found in the luminal proliferations unless there is a disintegration of the basement membrane with outgrowth of connective tissue between the epithelial ghost cells.

It was stated by Soluk Tekkesin et al[17] that intraosseous DGCTs are more aggressive than their extraosseous counterparts. More aggressive local resection is recommended for intraosseous variant, particularly if the tumor is radiologically ill-defined. The complete removal of the tumor may require block excision or segmental mandibular resection or partial maxillectomy, depending upon its size or anatomic extent[1]. The present case was treated with segmental resection. The patient is being followed up since one year and has shown no signs of recurrence. According to Garcia et al[18] and Sun et al[19] central DGCTs have been found to have a high rate of recurrence. Hence, it is strongly recommended to keep patients under long term follow-up.

DGCT is an uncommon odontogenic neoplasm, regarded as a solid variant of the COC. Only 2%-14% of COCs are solid tumors considered as DGCTs. In this article, we reported a case of 18 year old male patient, who presented with chief complaint of swelling over upper left region of the jaw. To arrive at a definitive diagnosis, routine histopathological examination was carried out with H and E along with van Gieson’s staining, which demonstrated the characteristic features of DGCT. DGCT is a rare entity but local recurrences have been reported due to its inherent tendency and insufficient removal of the lesion. The present case, following enucleation, showed recurrence twice in a span of four years after the initial diagnosis, suggesting that the lesion began at a much younger age that is at 14 years. Hence, owing to the aggressive nature and high rate of recurrence of DGCT, it should be treated with a more radical approach. Long term patient follow-up is mandatory as recurrences over 5-8 years following primary treatment have been reported irrespective of the mode of surgical treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pameijer CH, Vieyra JP, Gorseta K, Munhoz EA, Huo Q S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Rai S, Prabhat M, Goel S, Bhalla K, Panjwani S, Misra D, Agarwal A, Bhatnagar G. Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor - a neoplastic variety of calcifying odontogenic cyst: case presentation and review. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7:19-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sonawane K, Singaraju M, Gupta I, Singaraju S. Histopathologic diversity of Gorlin's cyst: a study of four cases and review of literature. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2011;12:392-397. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Singhaniya SB, Barpande SR, Bhavthankar JD. Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2009;13:97-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Takata T, Grandis JR, Slootweg PJ. The fourth edition of the head and neck World Health Organization blue book: editors' perspectives. Hum Pathol. 2017;66:10-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Fejerskov O, Krogh J. The calcifying ghost cell odontogenic tumor - or the calcifying odontogenic cyst. J Oral Pathol. 1972;1:273-287. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Thinakaran M, Sivakumar P, Ramalingam S, Jeddy N, Balaguhan S. Calcifying ghost cell odontogenic cyst: A review on terminologies and classifications. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16:450-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hong SP, Ellis GL, Hartman KS. Calcifying odontogenic cyst. A review of ninety-two cases with reevaluation of their nature as cysts or neoplasms, the nature of ghost cells, and subclassification. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:56-64. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Toida M. So-called calcifying odontogenic cyst: review and discussion on the terminology and classification. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:49-52. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Bafna SS, Joy T, Tupkari JV, Landge JS. Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2016;20:163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kumar U, Vij H, Vij R, Kharbanda J, Aparna I, Radhakrishnan R. Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor of the peripheral variant mimicking epulis. Int J Dent. 2010;2010:519494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rojo R, Prados-Frutos JC, Gutierrez Lázaro I, Herguedas Alonso JA. Calcifying odontogenic cysts. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;118:122-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shah K. Research Article Dentinogenic Ghost Cell Tumor-A Case Report. IJCR. 2018;10:72052-72054. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Agrawal Y, Naidu GS, Makkad RS, Nagi R, Jain S, Gadewar DR, Kataria R. Dentinogenic ghost cell tumor-a rare case report with review of literature. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2017;7:598-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | de Arruda JAA, Monteiro JLGC, Abreu LG, de Oliveira Silva LV, Schuch LF, de Noronha MS, Callou G, Moreno A, Mesquita RA. Calcifying odontogenic cyst, dentinogenic ghost cell tumor, and ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma: A systematic review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47:721-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Konstantakis D, Kosyfaki P, Ebhardt H, Schmelzeisen R, Voss PJ. Intraosseous dentinogenic ghost cell tumor: a clinical report and literature update. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42:e305-e311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Buchner A, Akrish SJ, Vered M. Central Dentinogenic Ghost Cell Tumor: An Update on a Rare Aggressive Odontogenic Tumor. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74:307-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Soluk Tekkesin M, Erdem MA, Ozer N, Olgac V. Intraosseous and extraosseous variants of dentinogenic ghost cell tumor: two case reports. J Istanb Univ Fac Dent. 2015;49:56-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Garcia BG, Masera JJ, Camacho FM, Gutierrez CC. Intraosseous dentinogenic ghost cell tumor: Case report and treatment review. Revista Española de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial. 2015;37:243-246. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sun G, Huang X, Hu Q, Yang X, Tang E. The diagnosis and treatment of dentinogenic ghost cell tumor. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:1179-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |