Published online Sep 5, 2022. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v13.i5.67

Peer-review started: April 13, 2022

First decision: June 16, 2022

Revised: June 22, 2022

Accepted: August 1, 2022

Article in press: August 1, 2022

Published online: September 5, 2022

Processing time: 139 Days and 18.1 Hours

In monotherapy studies for bleeding peptic ulcers, large volumes of epinephrine were associated with a reduction in rebleeding. However, the impact of epine

To assess whether epinephrine volume was associated with bleeding outcomes in individuals who also received endoscopic thermal therapy and/or clipping.

Data from 132 patients with Forrest class Ia, Ib, and IIa peptic ulcers were reviewed. The primary outcome was further bleeding at 7 d; secondary outcomes included further bleeding at 30 d, need for additional therapeutic interventions, post-endoscopy blood transfusions, and 30-day mortality. Logistic and linear regression and Cox proportional hazards analyses were performed.

There was no association between epinephrine volume and all primary and secondary outcomes in multivariable analyses. Increased odds for further bleeding at 7 d occurred in patients with elevated creatinine values (aOR 1.96, 95%CI 1.30-3.20; P < 0.01) or hypotension requiring vasopressors (aOR 6.34, 95%CI 1.87-25.52; P < 0.01). Both factors were also associated with all secondary outcomes.

Epinephrine maintains an important role in the management of bleeding ulcers, but large volumes up to a range of 10-20 mL are not associated with improved bleeding outcomes among individuals receiving combination endoscopic therapy. Further bleeding is primarily associated with patient factors that likely cannot be overcome by increased volumes of epinephrine. However, in carefully-selected cases where ulcer location or size pose therapeutic challenges or when additional modalities are unavailable, it is conceivable that increased volumes of epinephrine may still be beneficial.

Core Tip: To our knowledge, this is the only study specifically aimed at clarifying the impact of epinephrine volume in patients treated with combination endoscopic therapy. Our findings suggest that larger volumes of epinephrine are unlikely to improve clinical outcomes among patients who also receive thermal therapy and/or clipping.

- Citation: Saffo S, Nagar A. Impact of epinephrine volume on further bleeding due to high-risk peptic ulcer disease in the combination therapy era. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2022; 13(5): 67-76

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v13/i5/67.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v13.i5.67

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is the most common cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), accounting for one-third to one-half of all cases[1-3]. Therapeutic endoscopic modalities are indicated for peptic ulcers with high-risk findings, including: (1) Spurting (Forrest class Ia); (2) Oozing (Forrest class Ib); or (3) Non-bleeding visible vessels (Forrest class IIa). Dilute epinephrine is a widely-available, safe, and effective therapy frequently used by endoscopists[4-6]. When it is injected circumferentially near an ulcer margin, epinephrine induces transient vasospasm and mechanical tamponade, often achieving rapid hemostasis. Clinical trials investigating this technique for monotherapy demonstrated that large volumes of epinephrine (up to 30-45 mL) are associated with a reduced risk for rebleeding[7-9].

In the last two decades, the combination of epinephrine with additional endoscopic modalities, including thermal therapy and/or clipping, for UGIB due to PUD has been shown to be more effective than epinephrine monotherapy in preventing rebleeding[10-11]. Guidelines have suggested that large volumes of epinephrine are not routinely necessary when additional endoscopic therapy is applied, and clinicians have anecdotally opted to use smaller quantities[5]. However, combination therapy studies have not assessed the impact of epinephrine volume on UGIB outcomes[12-22]. To address this ques

The study was exempted by the Institutional Review Board at Yale-New Haven Hospital. Electronic endoscopy records were queried from June 2017 to October 2020; 288 patients who underwent upper endoscopy for PUD and received endoscopic injection of dilute epinephrine (1:10000) at any point during the procedure were identified. Patients were subsequently excluded if they: (1) Did not have symptoms of overt bleeding; (2) Were not treated with combination endoscopic therapy; (3) Received interventions only for Forrest class IIb, IIc, or III ulcers; (4) Had multiple high-risk ulcers in different locations that required endoscopic treatment and could account for UGIB; (5) Received hemostatic spray (Hemospray®; Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana, United States); (6) Had missing data; or (7) Were initially screened into the cohort due to findings from interval endoscopies but did not meet the inclusion criteria at the time of index endoscopy. All patients received proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and our cohort included patients with both in-hospital and out-of-hospital UGIB.

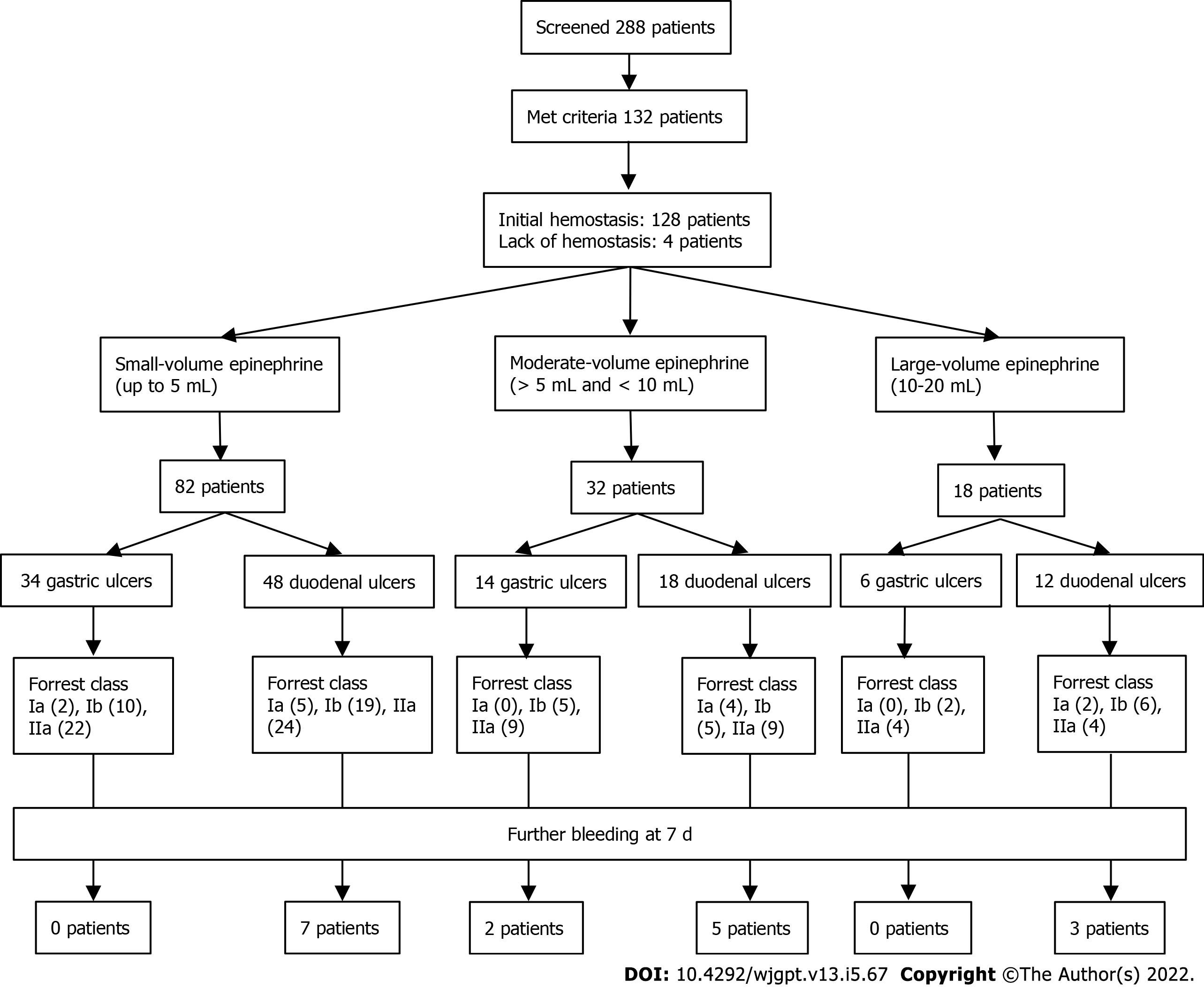

Clinical data were collected from the time of presentation up to a follow-up period of 30-days using electronic medical records (EMR). Presenting symptoms, vital signs, and labs were obtained from the initial emergency department or urgent care center evaluation for patients who experienced out-of-hospital bleeding. For patients who developed in-hospital bleeding, these variables were acquired at or near the time overt UGIB was documented. Medical history and medication data were attained from clinic, admission, and inpatient progress notes, nursing documentation, and medication administration records. Endoscopy records were reviewed for exam indications, findings, and interventions, including epinephrine volume and additional therapeutic maneuvers; endoscopic images were evaluated for clarification when deemed necessary. Epinephrine volume was categorized as follows: small (up to 5 mL), moderate (more than 5 mL but less than 10 mL), or large (10 mL or more).

The primary outcome was further rebleeding, defined as the presence of either: (1) Persistent bleeding without successful hemostasis at the time of index endoscopy; or (2) Rebleeding from the index source within 7 d of initial hemostasis based on clinical assessment by a gastroenterologist. Secondary outcomes included: (1) Further bleeding within 30 d of index endoscopy; (2) Need for additional therapeutic interventions; including endoscopic therapies; vascular embolization, or surgery; (3) Post-endoscopy blood transfusions; measured as units of packed red blood cells (pRBCs) administered after the initial endoscopy; (4) All-cause mortality at 30 d; and (5) Serious adverse effects (AEs) attributed to epinephrine use; including ventricular arrhythmias or cardiac ischemia. The etiology of bleeding, occurrence of rebleeding or AEs, and cause of death were determined by the authors of this study by synthesizing assessments in the EMR from gastroenterology, internal medicine, critical care, surgery, and/or interventional radiology (IR) providers.

The impact of endoscopic findings, including ulcer location, absolute size, and Forrest classification (Ia/Ib vs IIa), on the absolute volume of epinephrine injected was examined using a multivariable linear regression model. For the main analyses, logistic and linear regression and Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the impact of epinephrine volume on UGIB outcomes in relation to the effect of other relevant covariates, including age, presenting features (admission status, presence of hematochezia, creatinine levels, and hypotension requiring vasopressors), comorbidities [cardiovascular disease and congestive heart failure), medications (antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulant, and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use], and endoscopic factors (time to endoscopy, ulcer location, Forrest classification, and size). Epinephrine volume was assessed as a continuous variable; the remaining covariates were dichotomized with the exception of creatinine values, which were also maintained as continuous variables. Variables with P values less than 0.05 in univariable analyses were subsequently included in multivariable analyses. All analyses were performed in R (R Core Team, 2019); survival analysis was done using the survival package[23].

During a period of more than three years, 132 PPI-treated patients received combination endoscopic therapy that included epinephrine injection for Forrest class Ia, Ib, and IIa ulcers in the stomach or duodenum and met the remaining criteria for our study (Figure 1 and Table 1). Our cohort predominantly consisted of elderly individuals who had comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular disease (42%) or chronic renal dysfunction (45%) and used one or more antiplatelet agents, NSAIDs, and/or anticoagulants (70%). In-hospital bleeding was common (48%); half were either already in the intensive care unit (ICU) or required admission to the ICU and 30% needed vasopressors for hypotension. Endoscopy occurred at a mean time of 29 h (standard deviation 29 h, range 1-199 h). Ulcers were present in the following locations: 8 (6%) in the gastric cardia, 7 (5%) in the gastric fundus, 23 (17%) in the gastric body, 1 (1%) in the gastric incisura, 15 (11%) in the gastric antrum, 57 (43%) in the first portion of the duodenum, 20 (15%) in the second portion of the duodenum, and 1 (1%) in the third portion of the duodenum. Ulcer size ranged from 2 to 50 mm, and actively bleeding ulcers (Forrest class Ia or Ib) were encountered in 45% of cases. The mean volume of epinephrine was 5.5 mL (standard deviation 3 mL, range 1-20 mL), and 18 patients (14%) received 10 or more mL. There was no association between the volume used and ulcer location (P = 0.50), ulcer size (P = 0.15), or Forrest classification (P = 0.92).

| Demographics | n (%) | mean ± SD | Medications | n (%) | mean ± SD |

| Age (yr) | 70 ± 16 | Antiplatelet agents | 64 (48) | ||

| Sex (male) | 86 (65) | Anticoagulants | 36 (27) | ||

| Race (White) | 96 (73) | NSAIDs | 28 (21) | ||

| Presentation | Medical interventions | ||||

| In-hospital bleeding | 64 (48) | ICU admission | 66 (50) | ||

| Hematemesis | 25 (19) | Hypotension requiring vasopressors | 39 (30) | ||

| Melena | 93 (70) | Blood transfusion (units) | 4 ± 4 | ||

| Hematochezia | 29 (22) | ||||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 112 ± 22 | Endoscopic findings | |||

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 63 ± 14 | Time to endoscopy (h) | 29 ± 29 | ||

| Heart rate (BPM) | 95 ± 19 | Ulcer location (gastric) | 54 (41) | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8 ± 2 | Forrest classification | |||

| Platelets (103/µL) | 275 ± 129 | Ia | 13 (10) | ||

| BUN (mg/dL) | 51 ± 29 | Ib | 47 (36) | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.6 ± 1 | IIa | 72 (55) | ||

| Glasgow-Blatchford score | 15 ± 3 | Size (mm) | 13 ± 9 | ||

| Medical history | Endoscopic interventions | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 55 (42) | Additional modality | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 37 (28) | Thermal therapy | 60 (45) | ||

| Active malignancy | 18 (14) | Clipping | 53 (40) | ||

| Chronic renal dysfunction | 59 (45) | Both thermal therapy and clipping | 19 (14) | ||

| Dialysis use | 22 (17) | Epinephrine volume (mL) | 5.5 ± 3 | ||

| Cirrhosis | 11 (8) | Large-volume epinephrine use (≥10 mL) | 18 (14) |

Initial endoscopic hemostasis was achieved in 128 patients (97%), and vascular embolization was performed by IR for the remaining 4 individuals. Among patients who had successful endoscopic hemostasis, rebleeding within 7 d occurred in 13 (10%) and rebleeding within 30 d occurred in 21 (16%); of those who had failure of initial endoscopic hemostasis, one experienced rebleeding less than 48 h after endoscopy and embolization. Among all 22 (17%) patients who experienced rebleeding within 30 d, 19 (14%) required at least one additional endoscopic or endovascular intervention, including 10 (8%) who required endoscopic hemostasis, 3 (2%) who required vascular embolization, and 6 (5%) who required both; none required surgery. Among the entire cohort, 15 (11%) died within 30 d, and 5 deaths were due to probable refractory UGIB. No serious AEs attributed to epinephrine injection were reported.

In univariable logistic regression analysis, epinephrine volume did not correlate with further bleeding at 7 d (OR 1.06, 95%CI 0.92-1.22; P = 0.38); however, 4 other variables with P values < 0.05 were included in multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 2). Increased odds for further bleeding were observed in patients who had elevated creatinine values (aOR 1.96, 95%CI 1.30-3.20; P < 0.01) or hypotension requiring vasopressors (aOR 6.34, 95%CI 1.87-25.52; P < 0.01). This analysis was repeated using a follow-up period of 30 d. There was a positive association between increased epinephrine volume and further bleeding at 30 d in univariable analysis (OR 1.14, 95%CI 1.01-1.30; P = 0.03) but not in multivariable analysis (aOR 1.07; 95%CI 0.93-1.24; P = 0.31). Increased odds for further bleeding at 30 d were observed in those with elevated creatinine values (aOR 1.73, 95%CI 1.18-2.64; P < 0.01) or hypotension requiring vasopressors (aOR 7.68, 95%CI 2.69-24.38; P < 0.001) in multivariable analysis (Table 3).

| Variable | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Univariable logistic regression: | |||

| Age (≥ 75 yr) | 2.47 | 0.88-7.60 | 0.09 |

| Admission status (in-hospital) | 2.91 | 1.01-9.63 | 0.06 |

| Hematochezia | 2.96 | 0.98-8.6 | 0.04 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.86 | 1.31-2.78 | < 0.001 |

| Hypotension requiring vasopressors | 5.70 | 1.98-17.88 | < 0.01 |

| Cardiovascular disease and/or congestive heart failure | 2.71 | 0.94-8.98 | 0.08 |

| Antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulants, and/or NSAIDs | 0.57 | 0.20-1.70 | 0.30 |

| Time to endoscopy (> 24 h) | 0.71 | 0.23-2.00 | 0.53 |

| Location of ulcer (duodenal) | 6.19 | 1.65-40.43 | 0.02 |

| Forrest class (Ia and Ib) | 2.47 | 0.88-7.60 | 0.09 |

| Size of ulcer (> 20 mm) | 0.89 | 0.13-3.59 | 0.88 |

| Epinephrine volume (mL) | 1.06 | 0.92-1.22 | 0.38 |

| Multivariable logistic regression: | |||

| Hematochezia | 1.48 | 0.41-5.05 | 0.54 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.96 | 1.30-3.20 | < 0.01 |

| Hypotension requiring vasopressors | 6.34 | 1.87-25.52 | < 0.01 |

| Location of ulcer (duodenal) | 3.44 | 0.81-23.72 | 0.13 |

| Variable | aOR or aHR | 95%CI | P value |

| Further bleeding at 30 d1: | |||

| Hematochezia | 2.83 | 0.95-8.44 | 0.06 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.73 | 1.18-2.64 | < 0.01 |

| Hypotension requiring vasopressors | 7.68 | 2.69-24.38 | < 0.001 |

| Epinephrine volume (mL) | 1.07 | 0.93-1.24 | 0.31 |

| Need for additional therapeutic interventions1: | |||

| Admission status (in-hospital) | 1.36 | 0.37-5.18 | 0.64 |

| Hematochezia | 1.49 | 0.43-4.90 | 0.52 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.60 | 1.06-2.47 | 0.03 |

| Hypotension requiring vasopressors | 8.53 | 2.51-34.72 | < 0.01 |

| Epinephrine volume (mL) | 1.09 | 0.93-1.26 | 0.27 |

| Mortality at 30 d2: | |||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.77 | 1.36-2.30 | < 0.001 |

| Hypotension requiring vasopressors | 4.09 | 1.39-12.09 | 0.01 |

There was a positive association between increased epinephrine volume and the need for additional endoscopic or endovascular interventions in univariable logistic regression analysis (OR 1.14, 95%CI 1.00-1.30; P < 0.05) but not in multivariable logistic regression analysis (aOR 1.09; 95%CI 0.93-1.26; P = 0.27). Only elevated creatinine values (aOR 1.60, 95%CI 1.06-2.47; P = 0.03) and hypotension requiring vasopressors (aOR 8.53, 95%CI 2.51-34.72; P < 0.01) were associated with additional therapeutic interventions in multivariable analysis (Table 3).

A mean of 2 units of pRBCs were transfused after the initial endoscopy (standard deviation 3 units; range 0 to 14 units); 49 patients required no transfusions, 32 required 1 unit, and 51 required 2 or more units. In a univariable linear regression model, there was no correlation between epinephrine volume and the units of pRBCs transfused after initial endoscopy (P = 0.28). However, 6 other variables (admission status, presence of hematochezia, creatinine values, hypotension requiring vasopressors, time to endoscopy, and ulcer location) with P values < 0.05 in univariable linear regression models were included in a multivariable model (analysis not shown); increased post-endoscopy blood transfusions were only observed among patients with elevated creatinine values (P < 0.01) or hypotension requiring vasopressors (P < 0.001).

In a univariable Cox proportional hazards model, there was no association between epinephrine volume and death up to a follow-up of 30 d (HR 1.11, 95%CI 0.98-1.26; P > 0.10). In multivariable analysis (Table 3), elevated creatinine values (aHR 1.77, 95%CI 1.36-2.30; P < 0.001) and hypotension requiring vasopressors (aHR 4.09, 95%CI 1.39-12.09; P = 0.01) were associated with increased mortality.

Our study suggests that larger volumes of epinephrine up to a range of 10 to 20 mL for Forrest class Ia, Ib, and IIa PUD are unlikely to be associated with improved UGIB outcomes in the combination therapy era. In the context of improvements in standard medical therapy, including widespread PPI use, and the incorporation of additional endoscopic modalities such as thermal therapy and clipping, further bleeding due to therapeutic failure has become less common, and the relative impact of epinephrine volume is likely limited in most cases[24].

Our findings support the notion that adverse UGIB outcomes such as further bleeding, additional therapeutic interventions, excess transfusions, and death are more likely to occur as a result of general host factors rather than endoscopic factors among individuals receiving combination therapy. Patients with comorbidities such as renal dysfunction and hypotension requiring vasopressors may be less likely to have a favorable response to conventional medical and endoscopic therapies. The application of increased volumes of epinephrine up to the modest range evaluated in our study will likely not have a meaningful impact on outcomes.

Our study has some methodologic constraints, including a limited sample size, retrospective design, and data from one tertiary center. The majority of the patients in our cohort also received epinephrine injections of 1 to 5 mL, which is markedly less than the average volume (6 to 21 mL) reported in prior prospective combination therapy studies that included Forrest class Ia, Ib, and IIa ulcers[12-22]. In most cases included in our study, epinephrine was primarily used to improve visualization and limit bleeding as additional endoscopic hemostasis interventions were being applied. Ulcer characteristics, including location, size, and Forrest classification did not influence decisions relating to the volume of epinephrine use, indicating that providers were often only willing to use modest volumes, regardless of the technical aspects of the case. Only 18 patients received 10 or more mL of epinephrine, and the maximum volume used was 20 mL (one individual). Therefore, the impact of volumes greater than 10-20 mL in patients treated with combination therapy remains unclear.

The rates of rebleeding and further bleeding at 30 d among our cohort were 16% and 19%, respectively. These values were higher than anticipated for patients receiving combination therapy and may suggest that our study included an increased proportion of patients with risk factors for persistent bleeding or rebleeding, which is supported by the high rate of individuals requiring ICU admission among our cohort[11]. Although we attempted to address relevant covariates in our analyses, there may have been other unmeasured confounding variables that had some impact on outcomes, including the presence of coagulopathy, use of mechanical ventilation, or administration of other medications that may increase the risk for ulcer-related bleeding. Of the previously-cited prospective combination therapy studies that reported epinephrine volume, 10 of 11 reported rebleeding rates between 4% and 10% with no clear relationship to epinephrine volume (Table 4)[12-22].

| Ref. | Additional therapy | Mean volume (mL) | PPI | Forrest class | Number | Rebleeding | Follow-up | |

| Karaman et al[14], 2011 | Thermal | 6 | Yes | 1a and 1b | 78a | 4 | 5% | 4 wk |

| Kim et al[12], 2015 | Thermal | 6 | Yes | 1a, 1b, 2a | 151 | 12 | 8% | 30 d |

| Lin et al[20], 1999 | Thermal | 7 | Yes | 1a, 1b, 2a | 30 | 2 | 7% | 14 d |

| Tekant et al[22], 1995 | Thermal | 7 | No | 1b and 2a | 48b | 3 | 6% | 5 d |

| Chau et al[18], 2003 | Thermal | 8 | Yes | 1a, 1b, 2a | 164c | 34 | 21% | 10 d |

| Chung et al[19], 1999 | Thermal | 10 | No | 1a, 1b, 2a | 41 | 4 | 10% | 7 d |

| Lin et al[17], 2003 | Thermal and Clipping | 10 | Yes | 1a, 1b, 2a | 86 | 7 | 8% | 14 d |

| Chung et al[21], 1997 | Thermal | 10 | Some | 1a and 1b | 135 | 5 | 4% | 4 wk |

| Grgov et al[13], 2013 | Clipping | 11 | Yes | 1a, 1b, 2a | 35 | 2 | 6% | 8 wk |

| Bianco et al[16], 2004 | Thermal | 12 | Yes | 1a, 1b, 2a | 58 | 5 | 9% | 30 d |

| Taghavi et al[15], 2009 | Thermal and Clipping | 21 | Yes | 1a, 1b, 2a | 147c | 13 | 9% | 30 d |

| Total | 10 | 973 | 91 | 9% | ||||

Because of its availability, safety, and efficacy, epinephrine will continue to maintain an important role in the management of UGIB from PUD. However, in light of the other medical and endoscopic therapies that have emerged over the past 20 years, there is likely a limited role for the use of increased volumes of epinephrine for patients who require endoscopic therapy for high-risk PUD. Endoscopists should decide on the appropriate volume on a case-by-case basis depending on a combination of technical factors, including the magnitude of active bleeding encountered and ulcer location and size. Based on the findings of initial prospective monotherapy studies, there is minimal harm associated with the use of volumes up to 30-45 mL in most individuals[7-8]. Therefore, providers should not be reluctant to use large volumes if deemed necessary, and in cases where ulcer location or size pose therapeutic challenges or when additional modalities cannot be utilized, it is conceivable that this strategy may still be beneficial. However, large volumes of epinephrine will likely not overcome patient factors that are not readily modifiable and predispose to further bleeding.

In monotherapy studies for bleeding peptic ulcers, the volume of epinephrine injected had an impact on clinical outcomes. Large volumes up to a range of 30-45 mL were associated with a reduction in rebleeding. However, the impact of epinephrine volume on patients treated with combination endoscopic therapy remains unclear.

Understanding whether epinephrine volume can impact clinical outcomes among patients treated with combination endoscopic therapy can help inform clinical practice for the management of bleeding ulcers, a condition commonly encountered by endoscopists.

To examine whether epinephrine volume could impact the risk for further bleeding, need for additional medical or procedural interventions, and survival while accounting for other important clinical and endoscopic factors.

Comprehensive clinical and endoscopic data from 132 patients with Forrest class Ia, Ib, and IIa peptic ulcers treated at our tertiary care center were reviewed. We assessed for relevant clinical outcomes such as rebleeding within 7 and 30 d, need for additional intervention, post-endoscopy blood transfusions, and mortality. We used logistic regression analysis to determine the impact of clinical and endoscopic factors.

There was no association between epinephrine volume and rebleeding, need for additional intervention, post-endoscopy blood transfusions, or mortality. Increased odds for further bleeding at 7 d occurred in patients with elevated creatinine values (aOR 1.96, 95%CI 1.30-3.20; P < 0.01) or hypotension requiring vasopressors (aOR 6.34, 95%CI 1.87-25.52; P < 0.01). Both factors were also associated with all secondary outcomes.

Volumes of epinephrine up to a range of 10-20 mL are not associated with improved bleeding outcomes among individuals receiving combination endoscopic therapy. Further bleeding is primarily associated with patient factors that likely cannot be overcome by increased volumes of epinephrine, including the presence of shock and renal failure.

It is unlikely that large volumes of epinephrine are routinely necessary for the management of high-risk peptic ulcer disease. However, in select cases where ulcer characteristics pose therapeutic challenges or additional modalities are unavailable, it is conceivable that large volumes of epinephrine may still be beneficial.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American College of Gastroenterology; American Gastroenterological Association; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Akkari I, Tunisia; Sugimoto M, Japan S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Wuerth BA, Rockey DC. Changing Epidemiology of Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage in the Last Decade: A Nationwide Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:1286-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Enestvedt BK, Gralnek IM, Mattek N, Lieberman DA, Eisen G. An evaluation of endoscopic indications and findings related to nonvariceal upper-GI hemorrhage in a large multicenter consortium. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:422-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Lowe D, Travis SP, Murphy MF, Palmer KR. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60:1327-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 432] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mullady DK, Wang AY, Waschke KA. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Endoscopic Therapies for Non-Variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1120-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (39)] |

| 5. | Laine L, Barkun AN, Saltzman JR, Martel M, Leontiadis GI. ACG Clinical Guideline: Upper Gastrointestinal and Ulcer Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:899-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 70.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 6. | Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ, Lanas A, Sanders DS, Kurien M, Rotondano G, Hucl T, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Marmo R, Racz I, Arezzo A, Hoffmann RT, Lesur G, de Franchis R, Aabakken L, Veitch A, Radaelli F, Salgueiro P, Cardoso R, Maia L, Zullo A, Cipolletta L, Hassan C. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:a1-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ljubicic N, Budimir I, Biscanin A, Nikolic M, Supanc V, Hrabar D, Pavic T. Endoclips vs large or small-volume epinephrine in peptic ulcer recurrent bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2219-2224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liou TC, Lin SC, Wang HY, Chang WH. Optimal injection volume of epinephrine for endoscopic treatment of peptic ulcer bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3108-3113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lin HJ, Hsieh YH, Tseng GY, Perng CL, Chang FY, Lee SD. A prospective, randomized trial of large- vs small-volume endoscopic injection of epinephrine for peptic ulcer bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:615-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Baracat F, Moura E, Bernardo W, Pu LZ, Mendonça E, Moura D, Baracat R, Ide E. Endoscopic hemostasis for peptic ulcer bleeding: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2155-2168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vergara M, Bennett C, Calvet X, Gisbert JP. Epinephrine injection vs epinephrine injection and a second endoscopic method in high-risk bleeding ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD005584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim JW, Jang JY, Lee CK, Shim JJ, Chang YW. Comparison of hemostatic forceps with soft coagulation vs argon plasma coagulation for bleeding peptic ulcer--a randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2015;47:680-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grgov S, Radovanović-Dinić B, Tasić T. Could application of epinephrine improve hemostatic efficacy of hemoclips for bleeding peptic ulcers? Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:824-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Karaman A, Baskol M, Gursoy S, Torun E, Yurci A, Ozel BD, Guven K, Ozbakir O, Yucesoy M. Epinephrine plus argon plasma or heater probe coagulation in ulcer bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4109-4112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Taghavi SA, Soleimani SM, Hosseini-Asl SM, Eshraghian A, Eghbali H, Dehghani SM, Ahmadpour B, Saberifiroozi M. Adrenaline injection plus argon plasma coagulation vs adrenaline injection plus hemoclips for treating high-risk bleeding peptic ulcers: a prospective, randomized trial. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:699-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bianco MA, Rotondano G, Marmo R, Piscopo R, Orsini L, Cipolletta L. Combined epinephrine and bipolar probe coagulation vs. bipolar probe coagulation alone for bleeding peptic ulcer: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:910-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lin HJ, Perng CL, Sun IC, Tseng GY. Endoscopic haemoclip vs heater probe thermocoagulation plus hypertonic saline-epinephrine injection for peptic ulcer bleeding. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:898-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chau CH, Siu WT, Law BK, Tang CN, Kwok SY, Luk YW, Lao WC, Li MK. Randomized controlled trial comparing epinephrine injection plus heat probe coagulation vs epinephrine injection plus argon plasma coagulation for bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:455-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chung IK, Ham JS, Kim HS, Park SH, Lee MH, Kim SJ. Comparison of the hemostatic efficacy of the endoscopic hemoclip method with hypertonic saline-epinephrine injection and a combination of the two for the management of bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lin HJ, Tseng GY, Perng CL, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. Comparison of adrenaline injection and bipolar electrocoagulation for the arrest of peptic ulcer bleeding. Gut. 1999;44:715-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chung SS, Lau JY, Sung JJ, Chan AC, Lai CW, Ng EK, Chan FK, Yung MY, Li AK. Randomised comparison between adrenaline injection alone and adrenaline injection plus heat probe treatment for actively bleeding ulcers. BMJ. 1997;314:1307-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tekant Y, Goh P, Alexander DJ, Isaac JR, Kum CK, Ngoi SS. Combination therapy using adrenaline and heater probe to reduce rebleeding in patients with peptic ulcer haemorrhage: a prospective randomized trial. Br J Surg. 1995;82:223-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Therneau T. A Package for survival analysis in S. R package version 2.38, 2015. |

| 24. | Kim SB, Lee SH, Kim KO, Jang BI, Kim TN, Jeon SW, Kwon JG, Kim EY, Jung JT, Park KS, Cho KB, Kim ES, Kim HJ, Park CK, Park JB, Yang CH. Risk Factors Associated with Rebleeding in Patients with High Risk Peptic Ulcer Bleeding: Focusing on the Role of Second Look Endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:517-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |