Published online Mar 22, 2025. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v16.i1.101481

Revised: February 17, 2025

Accepted: February 25, 2025

Published online: March 22, 2025

Processing time: 183 Days and 11.2 Hours

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is typically treated with immunomodulators and steroids. However, some patients are refractory to these treatments, necessitating alternative approaches. Biological therapies have recently been explored for these difficult cases.

To assess the efficacy and safety of biologics in AIH, focusing on patients unre

A case-based systematic review was performed following the PRISMA protocol to evaluate the efficacy and safety of biological therapies in AIH. The primary focus was on serological improvement and histological remission. The secondary focus was on assessing therapy safety and additional outcomes. A standardized search command was applied to MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases to identify relevant studies. Inclusion criteria encompassed adult AIH patients treated with biologics. Data were analyzed based on demographics, prior treat

A total of 352 studies were reviewed, with 30 selected for detailed analysis. Key findings revealed that Belimumab led to a favourable response in five out of eight AIH patients across two studies. Rituximab demonstrated high efficacy, with 41 out of 45 patients showing significant improvement across six studies. Basiliximab was assessed in a single study, where the sole patient treated experienced a beneficial outcome. Additionally, a notable number of AIH cases were induced by anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) medications, including 16 cases associated with infliximab and four cases with adalimumab. All these cases showed improvement upon with

Belimumab and Rituximab show promise as effective alternatives for managing refractory AIH, demonstrating significant improvements in clinical outcomes and liver function. However, the variability in patient responses to different therapies highlights the need for personalized treatment strategies. The risk of AIH induced by anti-TNF therapies underscores the need for vigilant monitoring and prompt symptom recognition. These findings support the incorporation of biologic agents into AIH treatment protocols, particularly for patients who do not respond to conventional therapies.

Core Tip: This systematic review highlights the effectiveness of biologic therapies, such as Belimumab and Rituximab, in managing refractory autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) cases. Despite standard treatments with immunomodulators and steroids, some patients remain unresponsive, necessitating alternative options. The review found that Belimumab and Rituximab significantly improved clinical outcomes and liver function in these challenging cases. Additionally, anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies were associated with AIH induction, emphasizing the need for careful monitoring and early detection. These insights advocate for the inclusion of biologics in AIH treatment protocols for patients unresponsive to conventional the

- Citation: Eldew H, Soldera J. Evaluation of biological therapies in autoimmune hepatitis: A case-based systematic review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2025; 16(1): 101481

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v16/i1/101481.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v16.i1.101481

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic inflammatory liver disease affecting all ethnicities, with higher prevalence in northern Europeans and those with certain HLA types on chromosome 6. AIH type 1 is associated with HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR4, while other types involve HLA-DQB1 and HLA-DRB[1,2]. The immune-mediated inflammation can result in fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The exact aetiology is unknown, but environmental and genetic factors are believed to trigger hepatocyte damage and chronic inflammation. These include viruses (Hep A, C, D, CMV), drugs (minocycline, methyldopa, ticrynafen), and herbal agents[1-4]. AIH commonly affects young females.

AIH is classified into two types based on specific autoantibodies[1,5]. Type 1 is more prevalent in females with a ratio of 1:4 compared to males, particularly affecting those aged 10-30 and 40-60 years[2,6]. In type 1, autoantibodies include antinuclear antibody (ANA), smooth muscle antibody (SMA), perinuclear antineutrophil, and anti-soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas (anti-SLA/LP) and/or cytoplasmic autoantibody[1,5]. Type 2 primarily affects children[1,2] and is characterized by positive autoantibodies such as anti-liver kidney microsomal-1 (anti-LKM type 1 or type 3) and/or anti-liver cytosol-specific[6]. To provide further context, the immunological basis of AIH involves the immune system targeting liver cells, leading to chronic inflammation. Biologic therapies aim to modulate this immune response, particularly in ref

Another classification variant of AIH is based on overlap syndromes. The AIH-primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) overlap syndrome exhibits histological features of AIH and serological findings of PBC, including positive anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA). Conversely, the other variant shows histological features of PBC with serological markers of AIH, such as positive ANA and SMA, but is AMA-negative, sometimes termed autoimmune cholangitis or AMA-negative primary biliary cirrhosis. The AIH and sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome, which displays AIH serological features but primary sclerosing cholangitis characteristics on histology and cholangiography, has been well described[7]. Clinical presentation might range from asymptomatic cases to acute liver failure with jaundice, prolonged prothrombin time, and abnormal liver enzymes. Common symptoms include lethargy, anorexia, nausea, abdominal discomfort, pruritus, and arthralgia. Rare presentations may include encephalopathy, portal hypertension, and gas

AIH may present alongside other autoimmune disorders, such as type 1 diabetes, ulcerative colitis (UC), coeliac disease, and thyroiditis[1,8]. Hepatocellular carcinoma can be a late manifestation, highlighting the need for timely diagnosis and treatment to reduce mortality. The initial diagnostic workup involves evaluating liver function tests (LFT), including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase, which can be significantly elevated, ranging from 200-300 IU/L to thousands[11]. Elevated bilirubin levels may also indicate AIH with cholestasis.

Serological tests play a critical role in diagnosing AIH and its variants. For type 1 AIH, ANA are present in 43% of patients, and single-stranded and double-stranded DNA may also be detected. Anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA), SMA, which target actin, are found in 41% of type 1 cases. Type 2 AIH is identified by anti-LKM-1[8]. Additionally, 10 to 30% of AIH patients have positive anti-SLA/LP[12]. Diagnostic scoring systems, like the International AIH Group's scoring system, are useful for diagnosing cases lacking characteristic features[8]. Imaging studies, including abdominal ultrasound, are performed to rule out other liver conditions such as tumors, fatty liver, cirrhosis, gallstones, and cho

Liver histology is crucial before starting treatment for AIH to assess liver condition. A liver biopsy is highly reco

Corticosteroids combined with immunotherapy (AZA, MMF, ciclosporin) are preferred for treating AIH, especially for courses longer than six months[6]. While this therapy can control inflammation and achieve significant remission in some patients, others may experience disease recurrence or side effects. Continuous monitoring for potential complications is crucial, with monthly blood tests recommended for 3-6 months until AST and ALT levels normalize[12]. Biologics, including Rituximab, Rapamycin (Sirolimus), and Belimumab, are increasingly used for refractory AIH cases[16-18]. Unlike conventional treatments, which primarily focus on suppressing the immune response, biologic therapies target specific immune pathways involved in the pathogenesis of AIH, offering a more tailored approach for refractory cases.

This study aims to systematically review and analyse the existing literature on the efficacy and safety of biologics in AIH, focusing on patients unresponsive to standard treatments and evaluating outcomes such as serological markers and histological remission.

This case-based systematic review evaluates the efficacy of biological therapies in AIH, using the PRISMA checklist[19] for data collection.

Included were studies on adults (> 18 years) diagnosed with AIH via serology, imaging, or histology, treated with biological therapies, either alone or in combination with corticosteroids or immunosuppressants. The PICO criteria used for the search include: Population (adults diagnosed with AIH), intervention (conventional therapies, corticosteroids, or immunosuppressants with biological therapies), comparison [biological therapies vs other treatments, such as anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapies], outcomes (control of disease activity).

Exclusion criteria were patients < 18 years, studies not focused on AIH or biological therapies, or those with significant methodological flaws.

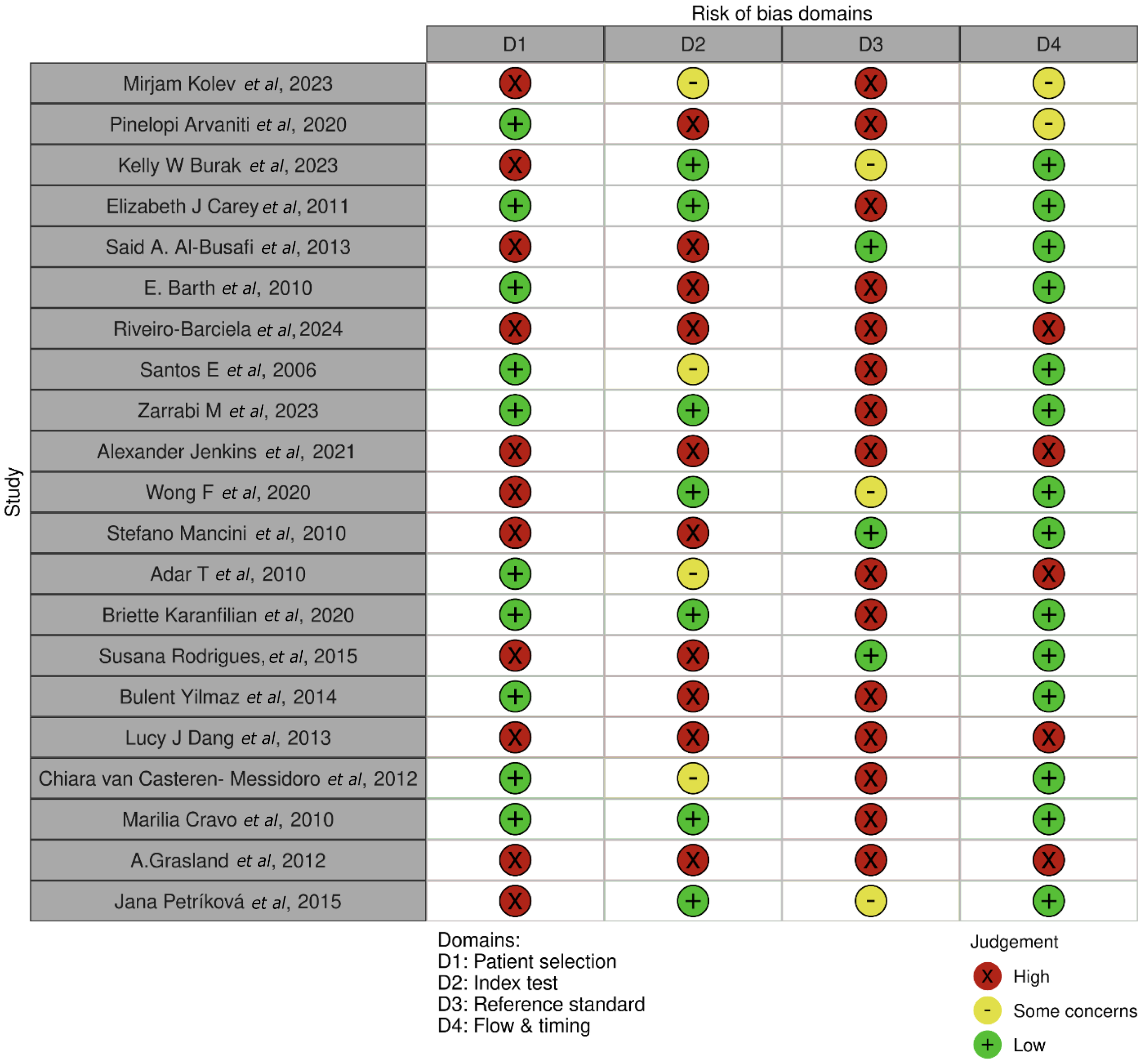

The risk of bias in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was assessed by the QUADAS-2 in observational studies[20], using the Cochrane Bias Assessment tool Robvis[21].

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and the University of South Wales databases, with no restrictions on publication type or language. The study, registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42024524959), filtered relevant case reports, case series, observational studies, and RCTs.

The search command used in this review was: ("autoimmune hepatitis" [All Fields] OR "AIH" [All Fields] OR "autoimmune liver disease" [All Fields]) AND ("biological therapy" [All Fields] OR "biologic therapy" [All Fields] OR "monoclonal antibodies" [All Fields] OR "rituximab” [All Fields] OR "infliximab” [All Fields] OR "TNF inhibitors" [All Fields] OR "anti-TNF therapy" [All Fields]) AND ("case reports" [Publication Type] OR "case series" [Publication Type] OR "observational study" [MeSH Terms]).

The study selection followed three phases: (1) Screening titles and abstracts; (2) Retrieving full-text articles based on inclusion criteria; and (3) Reviewing and extracting data from selected papers.

Data gathered from the included studies were organized into a preconceived form, allowing systematic extraction. The data was then analysed using frequencies, medians, and means, processed using Excel 365 to provide comprehensive insights into the study's outcomes.

The analysis of AIH treatment outcomes through various interventions is shown in Tables 1 and 2[22-42]. The studies were selected following specific eligibility criteria and using the PRISMA flow diagram, displayed in Figure 1. The bias assessment is displayed in Figure 2.

| Ref. | Country | Age | Patient-comorbidity | Type of AIH | Previous intervention | Intervention | Comparison | Study design | Outcomes measured | Result |

| Kolev et al[22] | Switzerland | 37-65 (6 pt) | There were 3 patients with AIH and 3 with PBC. Pt 1: AIH, Sjögren’s disease; Pt 2: AIH, PBC, Coeliac, Asthma; Pt 3: AIH, Autoimmune thyroiditis | 3 patients with type 1 AIH | Pt 1: Prednisolone, AZA, rituximab, MMF, UDCA; Pt 2: Prednisolone, AZA, UDCA, MMF, CyA; Pt 3: Prednisolone, AZA, MMF, budesonide, CyA | Belimumab 200 mg SC weekly | No comparison | Case series | Improvement of Fibroscan and normalization of AST and ALT | 3/3 patients respond positively to Belimumab |

| Arvaniti et al[23] | Greece | 27 and 58 | Pt 1: AIH, SLE, Hypergammaglobulinemia; Pt 2: Acute severe hepatitis | Refractory AIH | Pt 1: Prednisolone, AZA; Pt 2: Prednisolone, AZA and MMF | Belimumab: 10 mg/kg initially every 28 days | No comparison | Case series | Improvement of Fibroscan, Histology and normalization of AST and ALT | Both patients (2/2) achieved and maintained complete response to Belimumab |

| Burak et al[24] | Canada | 36-68 (6 pt) | Pt 1: T2DM, HTN; Pt 2: Osteoporosis; Pt 3: Asthma; Pt 4: None reported; Pt 5: CAD; Pt 6: CKD | Refractory AIH | Pt 1: Prednisone; Pt 2: Prednisone; Pt 3: Prednisone; Pt 4: AZA + MMF; Pt 5: Prednisone; Pt 6: Prednisone + AZA + MMF | Rituximab 1000 mg given each two weeks day 1 and 15 over 72 weeks | No comparison | Case series | Improvement of liver histology and of AST and ALT levels and reduction of steroids dose | All 6 patients had significant improvement histology: 4/6 improved inflammation grades in all and 2/6 patients improved fibrosis stages |

| Carey et al[25] | Arizona- United States | 44 | Several autoimmune disorders including Evan syndrome | Refractory AIH | Prednisolone and AZA | Rituximab for 375 mg/m2 once a week /four weeks | No comparison | Case report | Normalization of haemoglobin, platelets, AST and ALT | Complete response |

| Al-Busafi et al[26] | Canada | 68 | Hypertension, osteoporosis and a Waldenström macroglobulinemia | Refractory AIH | Prednisone | Rituximab given as high-dose-rituximab four weekly 375 mg/m2 rituximab | No comparison | Case report | Histological, AST and ALT improvement | Partial responde, demanding the use of prednisone and AZA |

| Barth et al[27] | United States | 27 | B cell lymphoma | AIH intolerance to steroid | Prednisone | Rituximab 375 mg/m² weekly for 8 weeks and extra four weeks upon relapse | No comparison | Case report | Improvement in AST and ALT | Complete remission, with a relapse which responded to an increase of rituximab frequency |

| Riveiro-Barciela et al[28] | Barcelona | 19-73 (32 pts) | 10 patients with cirrhosis, 4 patients with overlap with PBC or PSC | Refractory AIH | Corticosteroids and immunosuppressive medications | Rituximab 1 g/2 weeks in (9%) patients, periodical doses in 32 (91%), fixed/6 months in 16 (46%) and 16 (46%) in periods | No comparison | Case series | Improvement in AST and ALT | Biochemical response in 31.89% patients, discontinuation of ≥ 1 immunosuppressive drugs in 47%, significant reduction in corticosteroid dose in most patients; safe even in cirrhotic patients |

| Santos et al[29] | United States | 52 | Asthma, DM, ITP | Refractory AIH | Methylprednisolone, prednisone, IV immune globulin (IVIG), anti-D immune globulin, danazol | Rituximab administration: 375 mg/m2 IV weekly for 4 weeks | No comparison | case report | Normalization of AST and ALT | Complete laboratorial remission |

| Zarrabi et al[30] | United States | 22 | PBC overlap, recurrent metastatic osteosarcoma | Refractory AIH | Steroids, tacrolimus and MMF | Basiliximab six doses of 20 milligrams/dose, then weekly for four weeks | No comparison | Case report | Normalization of AST and ALT | Complete and sustained response |

| Ref. | Country | Age | Comorbidities | AIH type | Previous intervention | Intervention | Comparison | Type of the study | Outcome | Result |

| Jenkins et al[31] | United States | 31 | UC | AIH induced by infliximab | Mesalamine, prednisone, adalimumab, Clostridioides difficile colitis | Suspension of Infliximab and use of Vedolizumab | None | Case report | AST and ALT improvement -AIH; Clinical and endoscopic improvement - UC | UC was controlled with the use of Vedolizumab AST and ALT normalized after infliximab was withdrawn |

| Wong et al[32] | Canada | 69 | AIH, HTN, diverticular disease | AIH induced by infliximab | Prednisolone | Infliximab | No comparison | Case report | Elevated AST and ALT, with elevated INR and positive ASMA and ANA. Liver biopsy showed multiacinar hepatocyte necrosis and interface hepatitis | Infliximab led to deterioration in liver markers compared to baseline instead of improvement |

| Mancini et al[33] | Italy | 33 | Psoriasis | AIH induced by infliximab | Methotrexate | Infliximab and prednisone | No comparison | Case report | Elevated AST and ALT levels, positive ANA and anti-dsDNA | Infliximab induced AIH |

| Adar et al[34] | Israel | 36 | Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, hypothyroidism, Crohn’s disease | AIH induced by adalimumab | AZA, methotrexate and prednisolone | Adalimumab | No comparison | Case report | Elevated AST and ALT and IgG levels, positive ANA and anti-DNA. Liver biopsy showed fibrosis, inflammatory cell infiltrate, interface hepatitis, and hepatic rosettes | Adalimumab induced AIH, which was discontinued due to adverse effects |

| Karanfilian et al[35] | United States | 37 | Crohn’s disease, psoriasis | AIH induced by infliximab | Prednisone | Infliximab | No comparison | Case report | Elevated AST and ALT, positive ANA and weakly positive smooth muscle antibody Liver biopsy showed active hepatitis with moderate interface activity, cholestasis, and infiltrate of eosinophils and plasma cells | Severe drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis secondary to infliximab and discontinuation of infliximab led to improvement in liver function tests |

| Rodrigues et al[36] | Portugal | 22-69 year (8 pts) | Ulcerative colitis, Ankylosing spondylitis, Psoriatic arthritis, Rheumatoid arthritis; Crohn’s disease, Palmoplantar pustular psoriasis | AIH induced by infliximab | Prednisone administered all AIH patients | Infliximab administered in 7 cases. Adalimumab administered in 1 case | No comparison | Case series | Infliximab: Six patients developed AIH and one patient developed DILI and cirrhosis | Normalisation of the liver function testes after discontinuation of anti-TNF |

| Yilmaz et al[37] | United States | 39 | Ankylosing spondylitis | AIH induced by infliximab | Methotrexate, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine | Infliximab | No comparison | Case report | ALT and AST elevated with positive ANA. Liver biopsy showed an acute autoimmune hepatitis with a lymph plasmatic infiltration | Normal liver function tests two months after discontinuation of the anti-TNF drug |

| Dang et al[38] | Australia | 47 | Chronic plaque psoriasis | AIH induced by infliximab | Methotrexate | Infliximab | No comparison | Case report | Elevated AST, ALT and IgG levels. Liver biopsy indicated acute AIH | Infliximab discontinued and liver condition improved |

| van Casteren-Messidoro et al[39] | Netherlands | 46 and 30 | Case 1: Crohn's disease, erythema nodosum; Case 2: UC | AIH induced by infliximab | Prednisone and AZA | Case 1: Infliximab; Case 2: Pregnant, infliximab and azathioprine | No comparison | Case series | Case 1: After the fourth infliximab dose, positive ANA and IgG; liver biopsy indicated acute AIH; Case 2: Elevated AST and ALT; liver biopsy showed hepatitis | In both cases liver enzymes improved after infliximab was withdrawn |

| Cravo et al[40] | Portugal | 38 | Crohn’s disease | AIH induced by infliximab | Azathioprine and prednisolone | Infliximab and Adalimumab | Infliximab vs Adalimumab | Case report | AIH induced by Infliximab and switched to adalimumab. Elevated AST and ALT and IgG with positive ANA, anti-dsDNA, and antihistone antibodies. Liver Biopsy showed chronic hepatitis and mild periportal fibrosis | Infliximab discontinued and with adalimumab liver function normalized |

| Grasland et al[41] | France | 35 | Hypertension, obesity | AIH induced by adalimumab | Methotrexate, prednisone, NSAIDs, paracetamol and etanercept | Adalimumab | Adalimumab vs Abatacept | Case report | AIH induced by Adalimumab - AST and ALT elevated | Adalimumab was discontinued and liver function improved Abatacept was restarted and liver enzymes normalized |

| Petríková et al[42] | Slovakia | 33 | Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis | AIH induced by adalimumab | Etanercept, certolizumab and anakinra | Adalimumab | No comparison | Case report | Increased AST, ALT, IgG and positive ASMA and AMA. Liver biopsy showed chronic hepatitis suggestive of AIH | Adalimumab induced autoimmune hepatitis and liver enzymes improved with withdrawal of adalimumab |

The literature search initially found 352 articles, and after removing duplicates, 350 articles remained. After screening titles and abstracts, 265 were excluded, including 17 without abstracts, 8 not involving anti-TNF therapy, and 47 deemed irrelevant or using different methodologies. A total of 85 studies were reviewed in detail. Of these, 30 were eligible for inclusion, while 55 were excluded due to age criteria (15), different methodologies (30), or insufficient data (10). The final quantitative synthesis included 30 articles. These were divided into two categories: Studies on biologics treating AIH (9, Table 1) and anti-TNF induced AIH (12, Table 2).

Kolev et al[22] reported a case series from Switzerland involving 6 patients aged 37-65 with type 1 AIH and other comorbidities. Belimumab was administered initially at 10 mg/kg IV, followed by 200 mg subcutaneously weekly. Results showed that 3 out of 3 patients responded well: One had normalized liver enzymes and Fibroscan, while two managed corticosteroid tapering successfully, with improved Fibroscan in all three. This study demonstrates the efficacy of Belimumab in complex cases of AIH, PBC, and Sjogren’s syndrome.

Arvaniti et al[23] conducted a case series in Greece on two patients aged 27 and 58 with refractory AIH, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other conditions. Belimumab was given at 10 mg/kg every 28 days, later adjusted to 21-40 days. Both patients experienced significant improvements in liver stiffness and histology, achieving remission with normalized liver enzymes and reduced ALT. The flexible dosing approach was highlighted as useful.

Burak et al[24] conducted a case series in Canada with 6 patients (aged 36-68) diagnosed with refractory AIH and comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, and chronic kidney disease. Rituximab was given at 1000 mg, two weeks apart. All patients showed significant improvement in AST and immunoglobulin G (IgG), with 3/6 reducing prednisolone dosage. ANA and ASMAs decreased, and liver biopsies showed inflammation improvement. Rituximab proved effective for refractory AIH and reducing steroid dependence.

Carey et al[25] described a 44-year-old female with refractory AIH and Evan syndrome. Rituximab led to normalized platelets, hemoglobin, and aminotransferases, achieving sustained remission.

Al-Busafi et al[26] reported a 68-year-old woman with refractory AIH, hypertension, and Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Rituximab at 375 mg/m² resulted in significant clinical and biochemical improvements and sustained remission.

Barth et al[27] studied a 27-year-old female with B-cell lymphoma and AIH. Rituximab 375 mg/m² weekly for 8 weeks initially reduced aminotransferases and lymphadenopathy. After a relapse, an additional 4 weeks of treatment norma

Riveiro-Barciela et al[28] analyzed 35 AIH patients (aged 19-73) from Spain's ColHai Registry. Rituximab, given in periodic or fixed doses, showed an 89% clinical benefit rate (CBR), with reduced corticosteroid use and no increased complications in cirrhosis patients. The study concluded Rituximab as an effective option, particularly in refractory cases.

Santos et al[29] presented a 52-year-old female with AIH, diabetes, and asthma. Rituximab normalized liver tests and stabilized platelet counts, achieving remission in both AIH and refractory immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Zarrabi et al[30] presented a case review of a 22-year-old female with AIH, PBC overlap, and metastatic osteosarcoma. Basiliximab was administered at 20 mg weekly for 4 weeks, while other conventional treatments (steroids, tacrolimus, MMF) were paused. The treatment led to the normalization of liver enzymes (LFTs), suggesting the potential efficacy and safety of Basiliximab in complex cases.

This section explores studies on the efficacy and safety of anti-TNF therapies like Infliximab and Adalimumab in AIH.

Jenkins et al[31] United States: A 31-year-old male with UC developed AIH after Infliximab. Liver enzymes normalized upon withdrawal, while UC was managed with Vedolizumab.

Wong et al[32], Canada: A 69-year-old male with AIH experienced severe liver impairment after Infliximab, requiring liver transplantation.

Mancini et al[33], Italy: A 33-year-old female with psoriasis developed AIH after Infliximab, which was managed with high-dose Prednisone.

Adar et al[34], Israel: A 36-year-old female with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and Crohn’s disease developed AIH after Infliximab.

Karanfilian et al[35], United States: A 37-year-old male with Crohn’s and psoriasis developed AIH after Infliximab. Liver function improved after switching to Prednisone.

Rodrigues et al[36], Portugal: Eight patients with autoimmune conditions developed AIH after anti-TNF therapy. Steroid therapy post anti-TNF discontinuation led to improvement.

Yilmaz et al[37], United States: A 39-year-old woman with ankylosing spondylitis developed AIH after Infliximab. Liver function normalized after stopping treatment.

Dang et al[38], Australia: A 47-year-old female with plaque psoriasis developed AIH after Infliximab, with improvement after discontinuation.

van Casteren-Messidoro et al[39], Netherlands: Two females, 46 and 30, with Crohn’s disease and UC, developed AIH after Infliximab, showing improved liver function after withdrawal.

Cravo et al[40], Portugal: A 38-year-old female with Crohn’s experienced AIH after Infliximab. Transitioning to Adalimumab improved liver function.

Grasland et al[41], France: A 35-year-old female with seronegative RA developed AIH after Adalimumab, with normalization of liver enzymes after switching to Abatacept.

Petríková et al[42], Slovakia: A 33-year-old female with Sjögren’s syndrome and RA developed AIH after Infliximab, Etanercept, and Adalimumab. AIH was managed with immunosuppressive therapy after discontinuation.

AIH is an autoimmune condition that targets liver cells, causing inflammation that can lead to either chronic damage or acute liver failure. While not all AIH patients require treatment, those with severe active disease should be treated. Severe AIH, as defined by Mack et al[8], involves high aminotransferase levels (over tenfold the normal range) and histological evidence such as multi-acinar or bridging necrosis. Acute or chronic AIH, particularly when marked by jaundice and a prolonged international normalised ratio of 1.5 to 2, but without encephalopathy, also warrants treatment[7,12].

The standard initial treatment for severe AIH includes corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents such as AZA or MMF. However, some patients exhibit intolerance or resistance to these therapies. Evidence suggests that certain cases are refractory, necessitating alternative treatments. This study aims to explore the efficacy and safety of biologics, specifically Rituximab and Belimumab, in comparison to anti-TNF agents such as Infliximab and Adalimumab, particularly for cases where standard therapies are insufficient.

The studies reviewed provide strong evidence for the effectiveness of biologics, such as Rituximab, Belimumab, and Basiliximab, in managing refractory AIH. Significant improvements were observed in histological markers and liver function among patients receiving liver biopsies, alongside notable clinical symptom relief. The findings indicate that biologics can successfully treat AIH with minimal side effects.

On the other hand, anti-TNF therapies like Infliximab and Adalimumab were found to induce AIH in patients treated for conditions such as UC, Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Patients often present elevated liver enzymes (AST, ALT) and positive autoimmune markers, such as ANA, ASMA, and dsDNA, with liver biopsies revealing typical AIH features, including inflammatory infiltrates and fibrosis.

In most cases, discontinuing the causative anti-TNF therapy led to normalization of liver enzymes and symptom improvement. Corticosteroids and alternative biologics, such as Vedolizumab and Abatacept, were effective in managing liver inflammation without triggering new episodes of AIH. For instance, Vedolizumab successfully managed UC after Infliximab was discontinued, Adalimumab was used effectively for Crohn’s disease, and Abatacept improved liver function in seronegative RA. The long-term safety profile of biologics other than anti-TNF agents appears superior, with no recurrence of AIH reported.

Belimumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to the B lymphocyte stimulator protein (BLys or BAFF), inhibiting B cell activity and reducing survival. While primarily indicated for systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis[43,44], data suggests potential efficacy in treating AIH. A study by Kolev et al[22] evaluated six patients, three of whom had AIH, with positive outcomes in those who previously failed conventional treatment. Two patients achieved complete response with normalized liver enzymes and improved FibroScan results, while the third patient experienced partial response, reducing prednisolone to 5 mg/day and showing improved liver function.

Another study by Arvaniti et al[23] focused on two patients with refractory AIH, who had partial responses to conventional treatments like corticosteroids and MMF. Both patients achieved complete remission following Belimumab treatment, with liver enzymes normalizing and improved liver stiffness noted on scans.

Belimumab demonstrated reduced inflammatory activity and histological improvement in these cases, highlighting its potential in managing AIH, especially in patients unresponsive to standard therapies.

Rituximab is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody used to treat autoimmune disorders such as RA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and pemphigus vulgaris, as well as lymphoproliferative diseases like chronic lymphocytic leukemia[45-47]. Rituximab works by targeting CD20 on B cells, reducing their activity, which is key in autoimmune diseases like AIH[46,47]. Administered intravenously, its dosing depends on the condition. Common side effects include cardiovascular issues, infections, and infusion reactions, which range from mild to severe[48,49].

Burak et al[24] conducted a case series involving six patients (aged 36-68) with refractory AIH who failed conventional treatments like corticosteroids and AZA. Rituximab, given at 1000 mg every two weeks, showed significant impro

In another case, a 44-year-old female with Evans syndrome and refractory AIH responded well to Rituximab after failing conventional therapies. After four weeks, she showed normalization of hemoglobin, platelets, and aminotransferases, with sustained remission for over a year[25]. Similarly, Al-Busafi et al[26] described a 68-year-old woman with refractory AIH and Von Willebrand Disease who also achieved stable remission with Rituximab. Another case, reported by Barth et al[27], involved a 27-year-old woman with AIH and B cell lymphoma who experienced resolved lymphadenopathy and decreased aminotransferase levels after Rituximab treatment.

The Coihai registry, the largest study on Rituximab in AIH, included 35 patients. It found that 31 of them, including 12 with refractory AIH, achieved CBR. Rituximab helped reduce or discontinue other immunosuppressive drugs, such as reducing Prednisolone from 20 mg to 5 mg/day. Notably, patients with cirrhosis showed no difference in CBR rates compared to those without cirrhosis (P = 0.319). The study highlighted the safety and efficacy of Rituximab, with fewer infusion reactions[28].

Santos et al[29] reported on a 52-year-old woman with AIH and ITP who achieved AIH remission and normalized liver enzymes with Rituximab, further supporting its effectiveness in managing AIH alongside other autoimmune conditions.

Basiliximab, a monoclonal antibody, acts as an immunosuppressant, primarily used to prevent organ rejection in kidney transplant patients. Its mechanism of action involves binding to the interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain (CD25) on T lymphocytes, inhibiting T cell activation and reducing the immune response, which is crucial in preventing organ rejection and disease activation[50].

Basiliximab is administered intravenously in single-dose vials of 10 or 20 mg. It is approved for preventing acute kidney transplant rejection and is also considered off-label for heart, lung, and liver transplants. Furthermore, it is being evaluated for treating autoimmune disease[51]. Side effects of Basiliximab include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, hypersensitivity reactions, and infections[51].

A case study by Zarrabi et al[30] showed promising results for using Basiliximab in AIH. A 22-year-old woman with AIH, PBC overlap, and metastatic osteosarcoma experienced normalization of LFT with no major side effects after Basiliximab treatment, indicating its potential in managing overlapping autoimmune liver diseases.

While biologics show promising results, anti-TNF agents in AIH carry significant risks, including the induction of AIH itself.

Infliximab, a purified DNA-derived chimeric IgG monoclonal antibody, inhibits TNF-alpha, which is active in acute phase reactions and systemic inflammation. It is produced by lymphocytes, NK cells, neutrophils, macrophages, mast cells, and neurons[52]. By blocking TNF-alpha, Infliximab halts the inflammatory cascade, improving conditions like Crohn’s disease and psoriasis[53]. Infliximab can be administered intravenously or subcutaneously and is linked to common side effects like headaches, rashes, and infusion reactions. More severe risks include tuberculosis, necessitating TB screening before treatment[53]. AIH has also been reported as a side effect.

Several case reports and studies support this finding. Jenkins et al[31] reported a case of a 31-year-old man treated with infliximab for UC who developed AIH. Discontinuing infliximab and switching to vedolizumab, alongside budesonide and AZA, normalized liver enzymes. Wong et al[32] discussed a 69-year-old man who developed AIH after three doses of infliximab, requiring a liver transplant due to hepatocyte necrosis. Mancini et al[33] described a 33-year-old woman with psoriasis who developed infliximab-related hepatitis, requiring prednisone for recovery. Additional studies by Karan

Adalimumab, another anti-TNF therapy, has been used since 2002 for autoimmune conditions like plaque psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis, RA, UC, and Crohn's disease[54]. Administered via subcutaneous injection, it carries side effects, including respiratory infections and headaches. It also increases lymphoma risk[54]. Our study examined Adalimumab induced cases of AIH.

Grasland et al[41] described a 35-year-old woman with RA who developed AIH after adalimumab treatment. Liver enzymes normalized after switching to abatacept. Similar findings were reported by Petríková et al[42] and Cravo et al[40], where patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, RA, and Crohn’s disease developed AIH after adalimumab use, confirmed by liver biopsies[42]. However, Cravo et al[40] highlighted a full recovery from AIH after infliximab discontinuation, with adalimumab successfully controlling the patient’s intestinal disease without AIH recurrence.

The varying outcomes of biologics and anti-TNF agents may be due to differences in their mechanisms of action. Belimumab targets BLyS, reducing B-cell activity and autoantibody production, addressing AIH’s autoimmune processes. Rituximab depletes B-cells by targeting CD20, also lowering autoimmune activity. In contrast, TNF-alpha inhibitors like infliximab and adalimumab disrupt immune responses, potentially triggering AIH, underscoring the complexity of immune modulation in AIH management.

Among reviewed articles, nine studies reported improvement of AIH using biologics like Rituximab, Belimumab, and Basiliximab, while twelve highlighted the development of AIH linked to anti-TNF therapies, specifically infliximab and adalimumab, when used for other autoimmune conditions[40].

Nevertheless, the use of anti-TNF therapies, particularly infliximab, has been explored as a potential treatment for refractory AIH in cases where standard or second-line therapies fail. A recent study demonstrated that infliximab can induce a complete biochemical response in up to 65% of patients with active AIH, which might support its role as a rescue therapy for those unresponsive to conventional treatments[55]. However, the presence of concomitant metabolic-associated liver disease significantly impacts the progression of liver fibrosis in AIH. A study by Liu et al[56] highlighted that patients with both AIH and MASLD, particularly those with diabetes mellitus, have a higher risk of developing severe fibrosis, further complicating disease management and increasing the likelihood of cirrhosis development. Thus, addressing steatosis and metabolic syndrome in AIH patients may be crucial for improving long-term liver outcomes and preventing fibrosis progression.

This study encountered several limitations related to the rarity of AIH. The small sample sizes in the available studies on biologics and anti-TNF therapies hinder the ability to detect significant differences, reducing the generalizability of the findings across larger populations. Genetic variability among patients further complicates treatment outcomes, making it difficult to predict responses accurately. Additionally, the high cost of biologics and anti-TNF agents limits their accessibility, potentially skewing the results towards patients who can afford these treatments. The lack of large-scale RCTs weakens the evidence base for biologic treatments in AIH, while heterogeneity in study design also limits the consistency of findings, and impaired our ability to run a meta-analysis. Thus, despite the promising results from biologics like Belimumab and Rituximab, the existing data remain constrained by these significant factors, and future research, such as RCTs, is crucial to overcome these challenges. Moreover, as our study is a systematic review, the sample size and patient heterogeneity is inherently constrained by the availability of published data, which may not fully capture the diversity of AIH presentations and treatment responses.

In conclusion, while biologics such as Belimumab and Rituximab show promise in treating AIH, anti-TNF therapies like Infliximab and Adalimumab may exacerbate or even induce AIH. Careful patient selection is essential, particularly for those with refractory AIH who fail to respond to standard treatments. Personalized approaches using genetic and biomarker analyses offer a pathway to optimize treatment and mitigate risks. However, the limitations surrounding small sample sizes, cost barriers, and genetic variability underscore the need for further research, especially large-scale RCTs, to solidify the efficacy and safety of biologics in AIH treatment. Such studies are also needed to explore why anti-TNF therapies lead to adverse effects while biologics have a more favorable profile.

We extend our appreciation to the Faculty of Life Sciences and Education at the University of South Wales for the Gas

| 1. | Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:54-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 636] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Czaja AJ. Autoimmune liver disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:234-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Franco DL, Kale S, Lam-Himlin DM, Harrison ME. Black Cohosh Hepatotoxicity with Autoimmune Hepatitis Presentation. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2017;11:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Soldera J. Immunological crossroads: The intriguing dance between hepatitis C and autoimmune hepatitis. World J Hepatol. 2024;16:867-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zachou K, Rigopoulou E, Dalekos GN. Autoantibodies and autoantigens in autoimmune hepatitis: important tools in clinical practice and to study pathogenesis of the disease. J Autoimmune Dis. 2004;1:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Moy L, Levine J. Autoimmune hepatitis: a classic autoimmune liver disease. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014;44:341-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ballotin VR, Bigarella LG, Riva F, Onzi G, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS, Soldera J. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome associated with inflammatory bowel disease: A case report and systematic review. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:4075-4093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mack CL, Adams D, Assis DN, Kerkar N, Manns MP, Mayo MJ, Vierling JM, Alsawas M, Murad MH, Czaja AJ. Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Adults and Children: 2019 Practice Guidance and Guidelines From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020;72:671-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 113.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Potts JR, Verma S. Optimizing management in autoimmune hepatitis with liver failure at initial presentation. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2070-2075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Braga AC, Vasconcelos C, Braga J. Pregnancy with autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2016;9:220-224. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Al-Chalabi T, Underhill JA, Portmann BC, McFarlane IG, Heneghan MA. Effects of serum aspartate aminotransferase levels in patients with autoimmune hepatitis influence disease course and outcome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1389-95; quiz 1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 659] [Cited by in RCA: 844] [Article Influence: 84.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging, Arif-Tiwari H, Porter KK, Kamel IR, Bashir MR, Fung A, Kaplan DE, McGuire BM, Russo GK, Smith EN, Solnes LB, Thakrar KH, Vij A, Wahab SA, Wardrop RM 3rd, Zaheer A, Carucci LR. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Abnormal Liver Function Tests. J Am Coll Radiol. 2023;20:S302-S314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dong Y, Potthoff A, Klinger C, Barreiros AP, Pietrawski D, Dietrich CF. Ultrasound findings in autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1583-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Gleeson D, Heneghan MA; British Society of Gastroenterology. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 2011;60:1611-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chatrath H, Allen L, Boyer TD. Use of sirolimus in the treatment of refractory autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Med. 2014;127:1128-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | D'Agostino D, Costaguta A, Álvarez F. Successful treatment of refractory autoimmune hepatitis with rituximab. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e526-e530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Selvarajah V, Montano-Loza AJ, Czaja AJ. Systematic review: managing suboptimal treatment responses in autoimmune hepatitis with conventional and nonstandard drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:691-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 39485] [Article Influence: 9871.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6953] [Cited by in RCA: 9507] [Article Influence: 679.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Synth Methods. 2021;12:55-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 613] [Cited by in RCA: 2499] [Article Influence: 499.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kolev M, Sarbu AC, Möller B, Maurer B, Kollert F, Semmo N. Belimumab treatment in autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cholangitis - a case series. J Transl Autoimmun. 2023;6:100189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Arvaniti P, Giannoulis G, Gabeta S, Zachou K, Koukoulis GK, Dalekos GN. Belimumab is a promising third-line treatment option for refractory autoimmune hepatitis. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Burak KW, Swain MG, Santodomingo-Garzon T, Lee SS, Urbanski SJ, Aspinall AI, Coffin CS, Myers RP. Rituximab for the treatment of patients with autoimmune hepatitis who are refractory or intolerant to standard therapy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Carey EJ, Somaratne K, Rakela J. Successful rituximab therapy in refractory autoimmune hepatitis and Evans syndrome. Rev Med Chil. 2011;139:1484-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Al-Busafi SA, Michel RP, Deschenes M. Rituximab for refractory autoimmune hepatitis: a case report. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2013;14:135-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Barth E, Clawson J. A Case of Autoimmune Hepatitis Treated with Rituximab. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;4:502-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Riveiro-Barciela M, Barreira-Díaz A, Esteban P, Rota R, Álvarez-Navascúes C, Pérez-Medrano I, Mateos B, Gómez E, De-la-Cruz G, Ferre-Aracil C, Horta D, Díaz-González Á, Ampuero J, Díaz-Fontenla F, Salcedo M, Ruiz-Cobo JC, Londoño MC. Rituximab is a safe and effective alternative treatment for patients with autoimmune hepatitis: Results from the ColHai registry. Liver Int. 2024;44:2303-2314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Santos ES, Arosemena LR, Raez LE, O'Brien C, Regev A. Successful treatment of autoimmune hepatitis and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with the monoclonal antibody, rituximab: case report and review of literature. Liver Int. 2006;26:625-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zarrabi M, Hamilton C, French SW, Federman N, Nowicki TS. Successful treatment of severe immune checkpoint inhibitor associated autoimmune hepatitis with basiliximab: a case report. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1156746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jenkins A, Austin A, Hughes K, Sadowski B, Torres D. Infliximab-induced autoimmune hepatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wong F, Al Ibrahim B, Walsh J, Qumosani K. Infliximab-induced autoimmune hepatitis requiring liver transplantation. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:2135-2139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Mancini S, Amorotti E, Vecchio S, Ponz de Leon M, Roncucci L. Infliximab-related hepatitis: discussion of a case and review of the literature. Intern Emerg Med. 2010;5:193-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Adar T, Mizrahi M, Pappo O, Scheiman-Elazary A, Shibolet O. Adalimumab-induced autoimmune hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e20-e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Karanfilian B, Mahpour N, Sarkar A. Infliximab Drug-Induced Autoimmune Hepatitis in a Patient With Crohn's Ileocolitis. Am J Ther. 2022;29:e741-e743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Rodrigues S, Lopes S, Magro F, Cardoso H, Horta e Vale AM, Marques M, Mariz E, Bernardes M, Lopes J, Carneiro F, Macedo G. Autoimmune hepatitis and anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy: A single center report of 8 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7584-7588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yilmaz B, Roach EC, Koklu S. Infliximab leading to autoimmune hepatitis: an increasingly recognized side effect. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2602-2603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Dang LJ, Lubel JS, Gunatheesan S, Hosking P, Su J. Drug-induced lupus and autoimmune hepatitis secondary to infliximab for psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:75-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | van Casteren-Messidoro C, Prins G, van Tilburg A, Zelinkova Z, Schouten J, de Man R. Autoimmune hepatitis following treatment with infliximab for inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:630-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cravo M, Silva R, Serrano M. Autoimmune hepatitis induced by infliximab in a patient with Crohn's disease with no relapse after switching to adalimumab. BioDrugs. 2010;24 Suppl 1:25-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Grasland A, Sterpu R, Boussoukaya S, Mahe I. Autoimmune hepatitis induced by adalimumab with successful switch to abatacept. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:895-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Petríková J, Jarčuška P, Svajdler M, Pella D, Macejová Z. Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by adalimumab and allergic reactions after various anti-TNFα therapy agents in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2015;17:256-258. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Iolascon G. What are the benefits and harms of belimumab for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus?: A Cochrane Review summary with commentary. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021;24:1331-1333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Furie R, Rovin BH, Houssiau F, Malvar A, Teng YKO, Contreras G, Amoura Z, Yu X, Mok CC, Santiago MB, Saxena A, Green Y, Ji B, Kleoudis C, Burriss SW, Barnett C, Roth DA. Two-Year, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Belimumab in Lupus Nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1117-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 583] [Article Influence: 116.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Hanif N, Anwer F. Rituximab, StatPearls [Online]. Treasure Island: StatPearl. Publishing, 2024. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Maloney DG, Smith B, Rose A. Rituximab: Mechanism of action and resistance. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:2-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Randall KL. Rituximab in autoimmune diseases. Aust Prescr. 2016;39:131-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption. StatPearls [Online]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2022. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, Dougados M, Furie RA, Genovese MC, Keystone EC, Loveless JE, Burmester GR, Cravets MW, Hessey EW, Shaw T, Totoritis MC; REFLEX Trial Group. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: Results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2793-2806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1121] [Cited by in RCA: 1205] [Article Influence: 63.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Kapic E, Becic F, Kusturica J. Basiliximab, mechanism of action and pharmacological properties. Med Arh. 2004;58:373-376. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Basiliximab. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2017. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Akiho H, Yokoyama A, Abe S, Nakazono Y, Murakami M, Otsuka Y, Fukawa K, Esaki M, Niina Y, Ogino H. Promising biological therapies for ulcerative colitis: A review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2015;6:219-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Fatima R, Bittar K, Aziz M. Infliximab. StatPearls [Online]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2024. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Ellis CR, Azmat CE. Adalimumab. StatPearls [Online]. Treasure island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2023. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Efe C, Lytvyak E, Eşkazan T, Liberal R, Androutsakos T, Turan Gökçe D, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Janik M, Bernsmeier C, Arvaniti P, Milkiewicz P, Batibay E, Yüksekyayla O, Ergenç I, Arikan Ç, Stättermayer AF, Barutçu S, Cengiz M, Gül Ö, Heurgue A, Heneghan MA, Verma S, Purnak T, Törüner M, Akdogan Kayhan M, Hatemi I, Zachou K, Macedo G, Drenth JPH, Björnsson E, Montano-Loza AJ, Wahlin S, Higuera-de la Tijera F. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Liu K, Feng M, Chi W, Cao Z, Wang X, Ding Y, Zhao G, Li Z, Lin L, Bao S, Wang H. Liver fibrosis is closely linked with metabolic-associated diseases in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatol Int. 2024;18:1528-1539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |