Published online Sep 28, 2024. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v16.i9.473

Revised: August 28, 2024

Accepted: September 3, 2024

Published online: September 28, 2024

Processing time: 100 Days and 8.5 Hours

Secondary rectal linitis plastica (RLP) from prostatic adenocarcinoma is a rare and poorly understood form of metastatic spread, characterized by a desmoplastic response and concentric rectal wall infiltration with mucosal preservation. This complicates endoscopic diagnosis and can mimic gastrointestinal malignancies. This case series underscores the critical role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in identifying the distinct imaging features of RLP and highlights the importance of considering this condition in the differential diagnosis of patients with a history of prostate cancer.

Three patients with secondary RLP due to prostatic adenocarcinoma presented with varied clinical features. The first patient, a 76-year-old man with advanced prostate cancer, had rectal pain and incontinence. MRI showed diffuse prostatic invasion and significant rectal wall thickening with a characteristic "target sign" pattern. The second, a 57-year-old asymptomatic man with elevated prostate-specific antigen levels and a history of prostate cancer exhibited rectoprostatic angle involvement and rectal wall thickening on MRI, with positron emission tomography/computed tomography PSMA confirming the prostatic origin of the metastatic spread. The third patient, an 80-year-old post-radical prostatectomy, presented with refractory constipation. MRI revealed a neoplastic mass infiltrating the rectal wall. In all cases, MRI consistently showed stratified thickening, concentric signal changes, restricted diffusion, and contrast enhancement, which were essential for diagnosing secondary RLP. Biopsies confirmed the prostatic origin of the neoplastic involvement in the rectum.

Recognizing MRI findings of secondary RLP is essential for accurate diagnosis and management in prostate cancer patients.

Core Tip: This study presents three cases of secondary rectal linitis plastica (RLP) due to prostate cancer, emphasizing the rarity and diagnostic challenges of this condition. The preservation of mucosa in RLP complicates endoscopic detection, making magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) crucial for early, accurate diagnosis. MRI findings, including stratified parietal thickening, restricted diffusion, and contrast enhancement, are pivotal in identifying RLP. Recognizing these patterns is essential for timely and appropriate management of metastatic rectal involvement, highlighting the need to consider RLP in patients with a history of prostate cancer.

- Citation: Labra AA, Schiappacasse G, Cocio RA, Torres JT, González FO, Cristi JA, Schultz M. Secondary rectal linitis plastica caused by prostatic adenocarcinoma - magnetic resonance imaging findings and dissemination pathways: A case report. World J Radiol 2024; 16(9): 473-481

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v16/i9/473.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v16.i9.473

Linitis plastica involves circumferential tumor infiltration of a hollow organ, which generates a desmoplastic reaction, causing stiffness and retraction of its walls[1,2]. The stomach is the most frequently affected organ; however, the small intestine, colon, and rectum can also be invaded[3,4]. The radiological expression of rectal linitis plastica (RLP) is less well known and can be confused with other etiologies, mainly of infectious or actinic inflammatory origin[5].

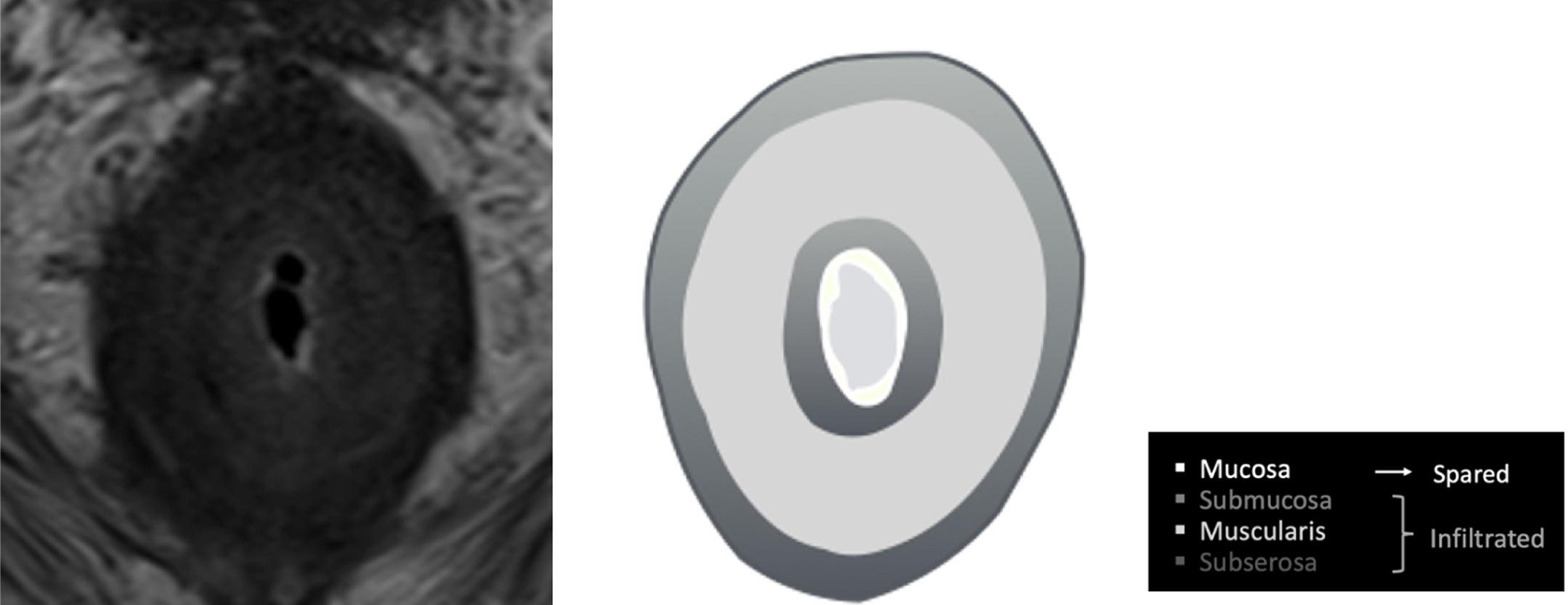

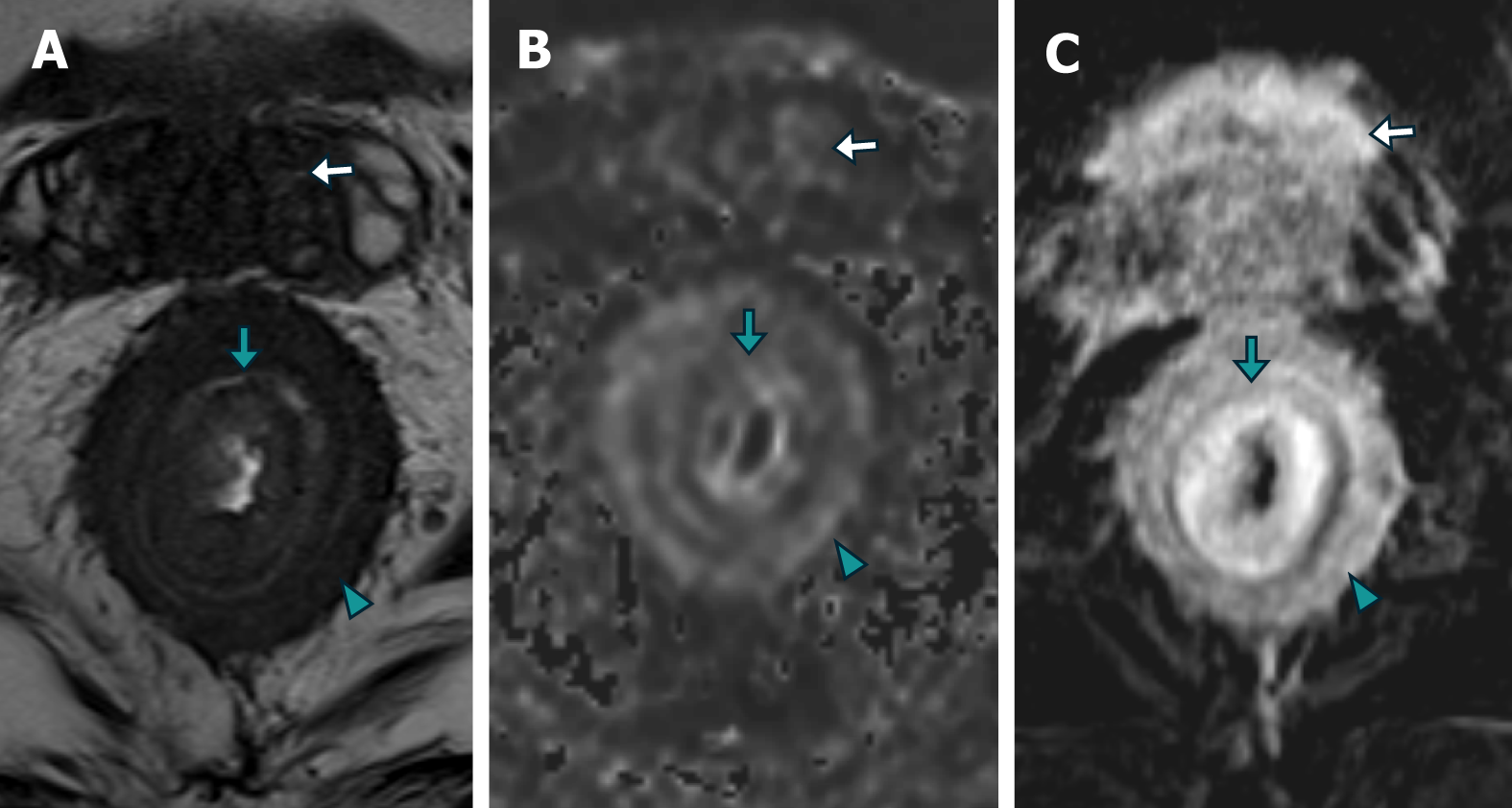

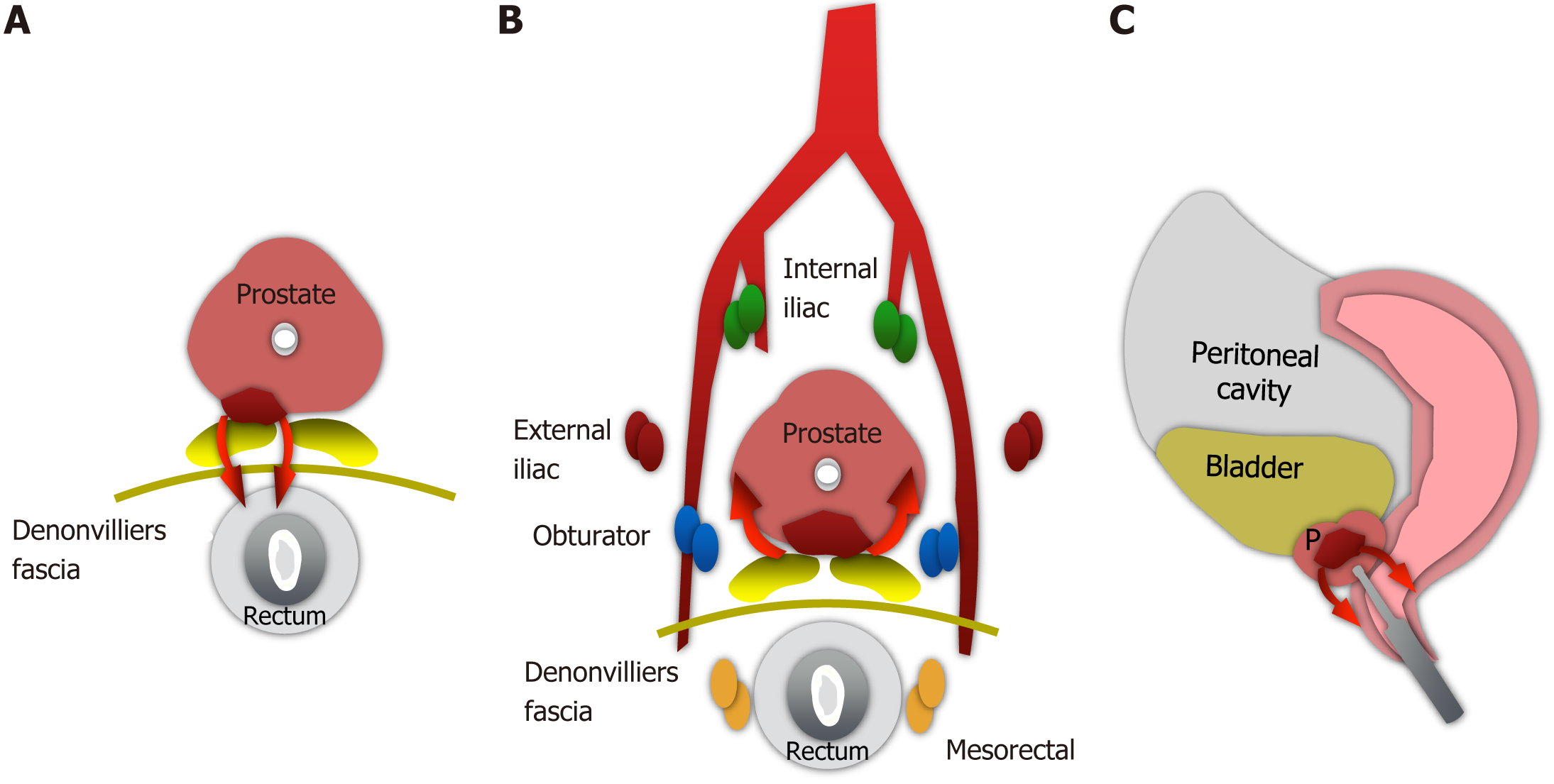

Secondary RLP caused by prostate neoplasia is a rare form of dissemination and has been poorly reported in the literature[4]. Histologically, it is characterized by an exuberant desmoplastic response, with concentric tumor infiltration of the submucosal, muscular, and subserosal layers, with the integrity of the mucosa[5], resulting in the normal anatomy becoming more pronounced, which has been described via magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (MRI) as concentric wall thickening, determining the "target sign" (Figure 1). The preservation of the rectal mucosa complicates its endoscopic diagnosis since epithelial lesions suggesting parietal involvement are not usually identified or are of minimal magnitude[6,7] (Figure 2).

The diagnosis is particularly challenging because these patients are often referred for MRI with a presumptive diagnosis of either inflammatory rectal disease or prostate cancer, leading to an MRI protocol tailored to these conditions. Moreover, diffuse involvement of the rectal layers may be easily overlooked if the referral lacks a precise differential diagnosis. Therefore, recognizing the characteristic MRI findings and understanding the pathways of metastasis from the prostate to the rectum are fundamental to guiding early and accurate diagnosis of RLP, directing therapeutic mana

Here, we report 3 cases of rectal neoplastic dissemination of the "linitis plastica" type secondary to prostate cancer, which were diagnosed via MRI with histological and/or functional confirmation. The objective is to demonstrate the metastatic involvement of the rectum by prostate cancer, with emphasis on the imaging findings on MRI and its routes of dissemination.

Patient 1: A 76-year-old man presented with rectal pain and fecal incontinence.

Patient 2: A 57-year-old asymptomatic man was found to have elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels during routine follow-up.

Patient 3: An 80-year-old man presented with refractory constipation.

Patient 1: He reported persistent rectal pain and new-onset fecal incontinence.

Patient 2: He presented with no symptoms.

Patient 3: He developed refractory constipation after initial management.

Patient 1: The patient had been diagnosed with locally advanced prostate cancer with a Gleason score of 5 + 3 and was receiving hormone therapy.

Patient 2: The patient had a history of prostate cancer and was diagnosed via systematic transrectal biopsy (Gleason score of 4 + 3).

Patient 3: The patient had undergone radical prostatectomy and lymphadenectomy for prostate cancer 12 years prior (Gleason score of 4 + 3).

Patient 1: The physical examination revealed a hard prostate that was adherent to adjacent tissues.

Patient 2: Physical examination did not reveal any abnormal findings.

Patient 3: Physical examination revealed a 3 cm nodule in the right lobe.

Patient 1: A laboratory study revealed a PSA level of 8.4 ng/mL, with no other relevant findings.

Patient 2: The PSA level was significantly elevated at 100 ng/mL.

Patient 3: Laboratory examination details were not available.

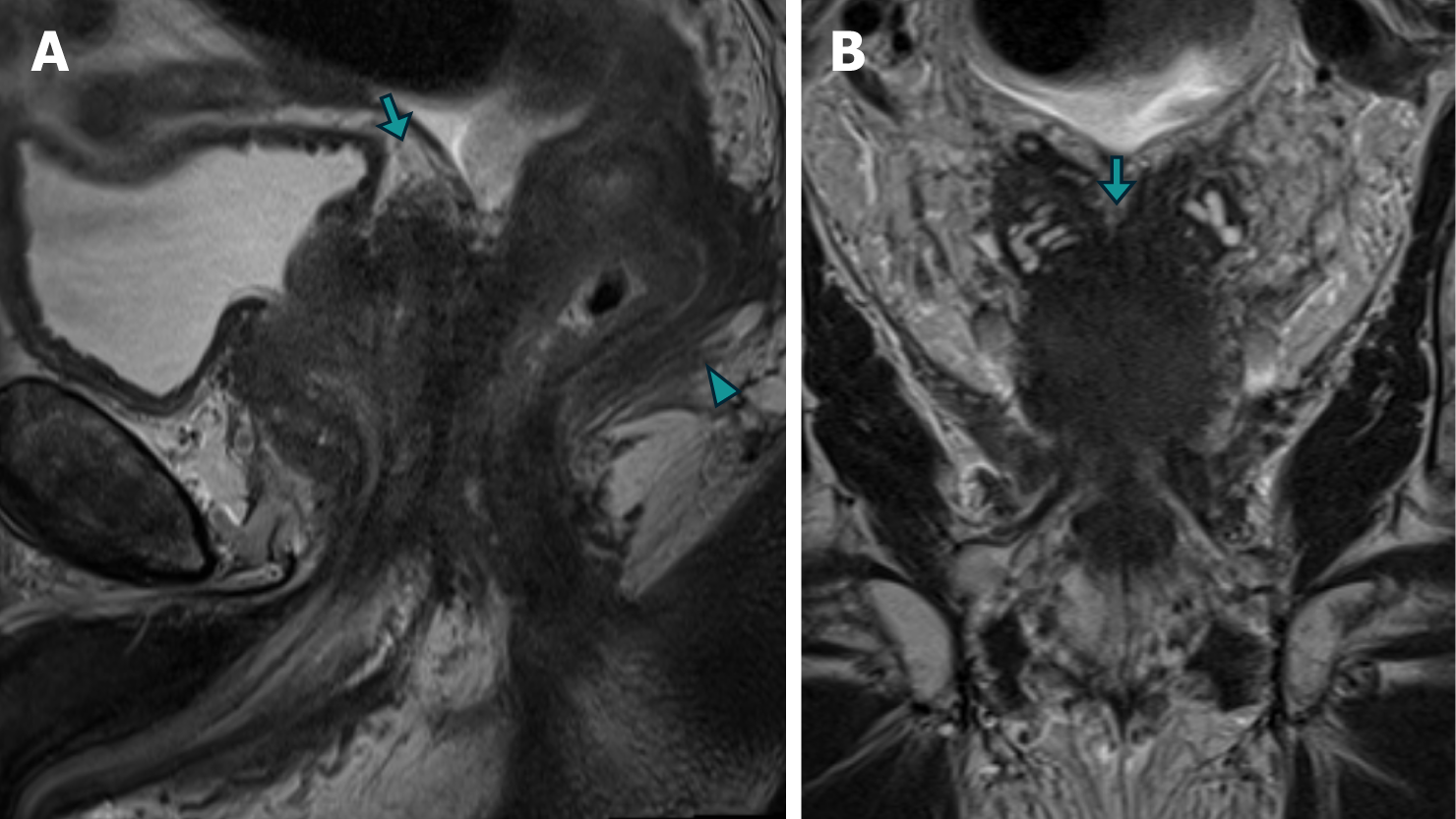

Patient 1: An MRI of the prostate revealed diffuse neoplastic involvement of the prostatic parenchyma in both the peripheral and transitional zones. The images revealed poorly defined hypointense areas in the T2 sequence, restricted diffusion in diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and early enhancement in the inferior vena cava (IVC) study. Addi

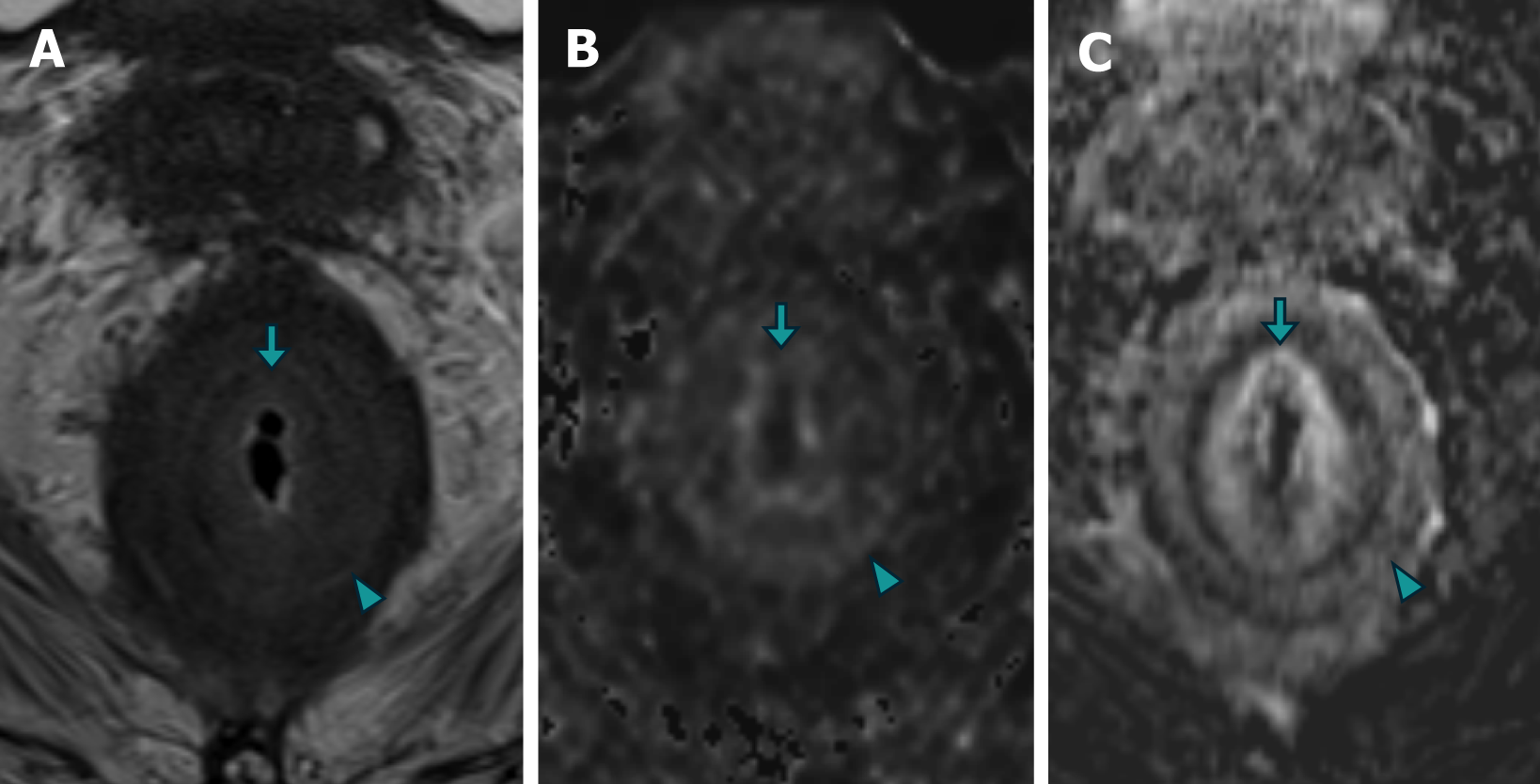

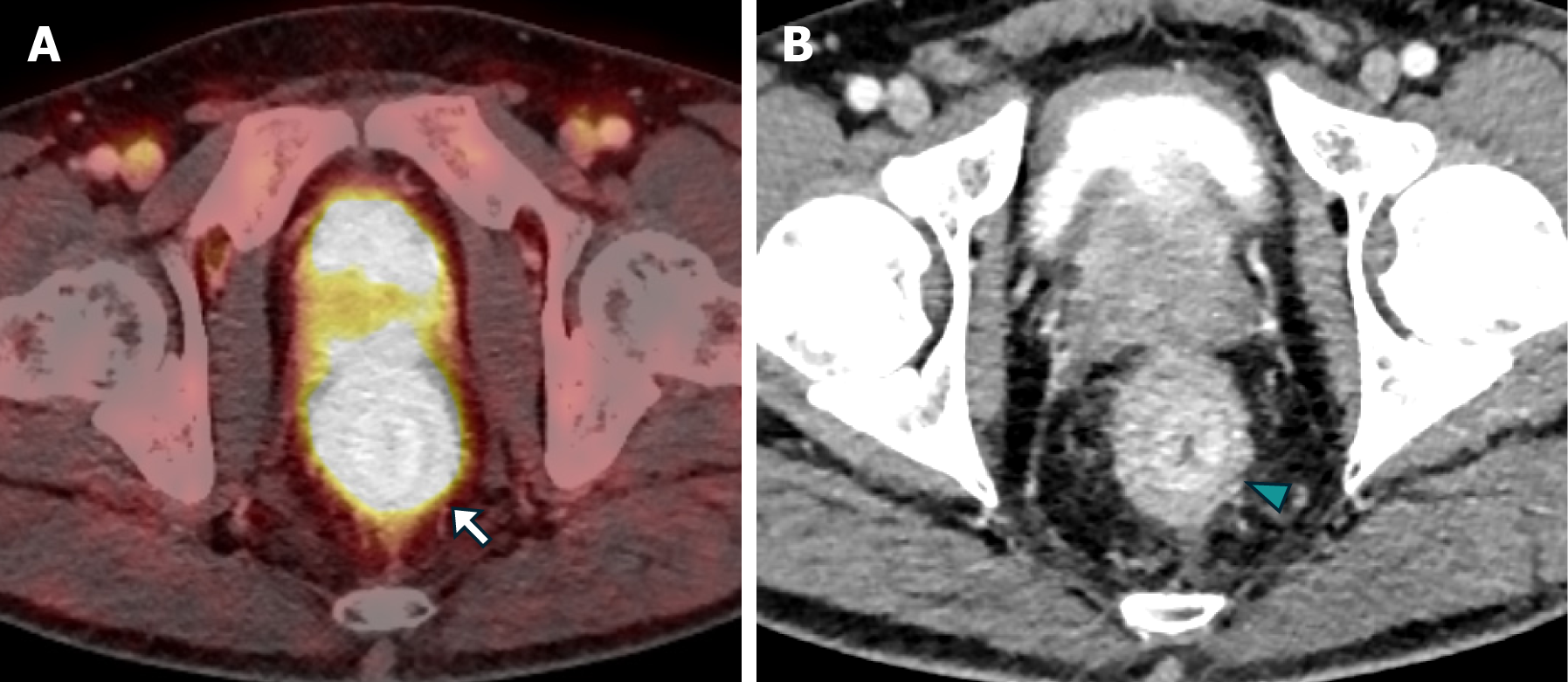

Patient 2: MRI revealed diffuse neoplastic involvement of the prostatic parenchyma in both the transitional and peripheral zones, with poorly defined hypointense areas in the T2 sequence, restricted diffusion in DWI, and early enhancement in the IVC study. Notably, there was involvement of the rectoprostatic angles, infiltration of the right neurovascular complex, and extension to the rectal wall, characterized by stratified parietal thickening, concentric areas of intermediate signal intensity in the T2 sequence, restricted diffusion in DWI, and contrast enhancement in the IVC study, involving both the submucosal, muscular, and subserosal planes, suggestive of a "linitis plastica" pattern (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) PSMA confirmed the prostatic origin of neoplastic infiltration with significant uptake of the radiotracer at the rectal level (Figure 7).

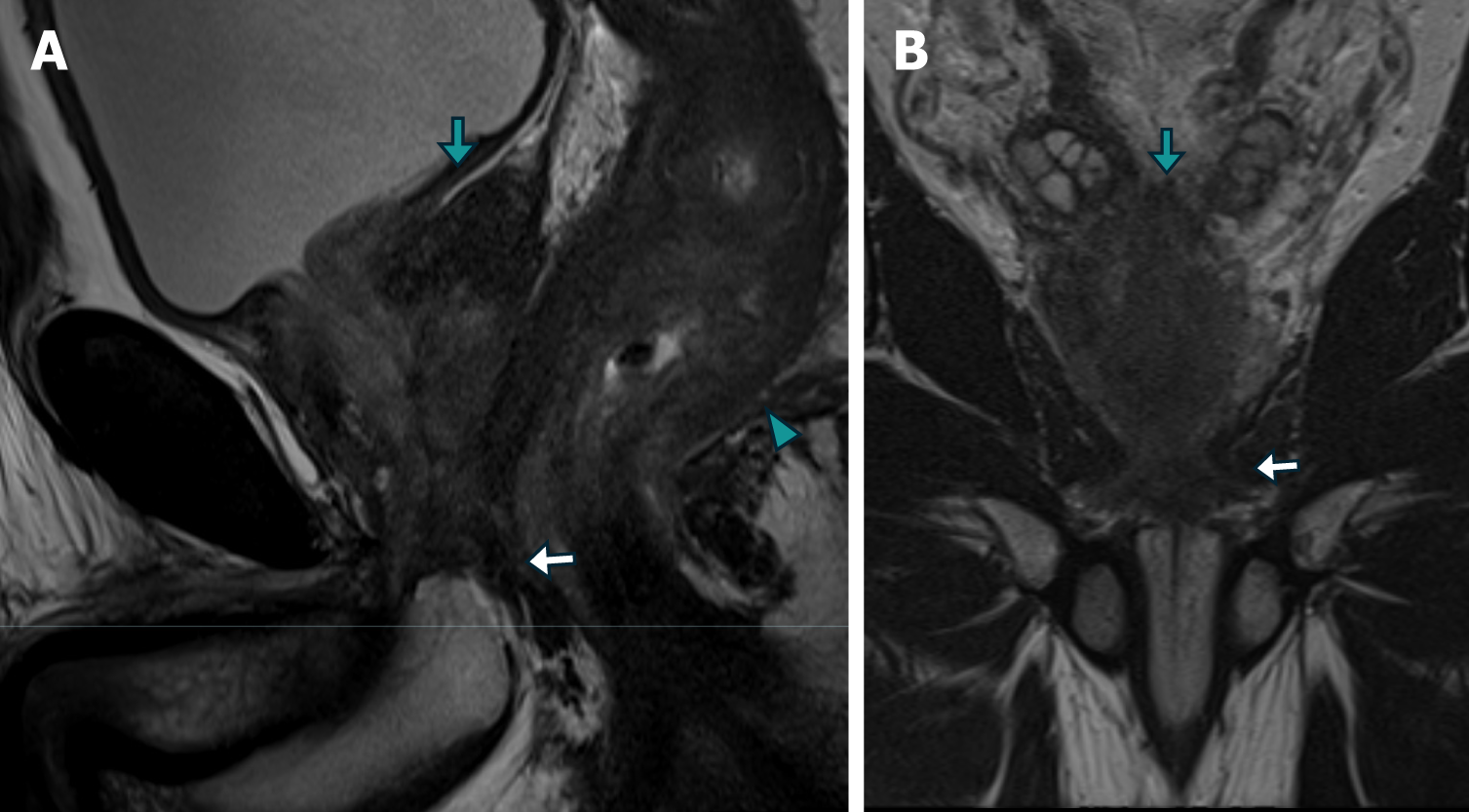

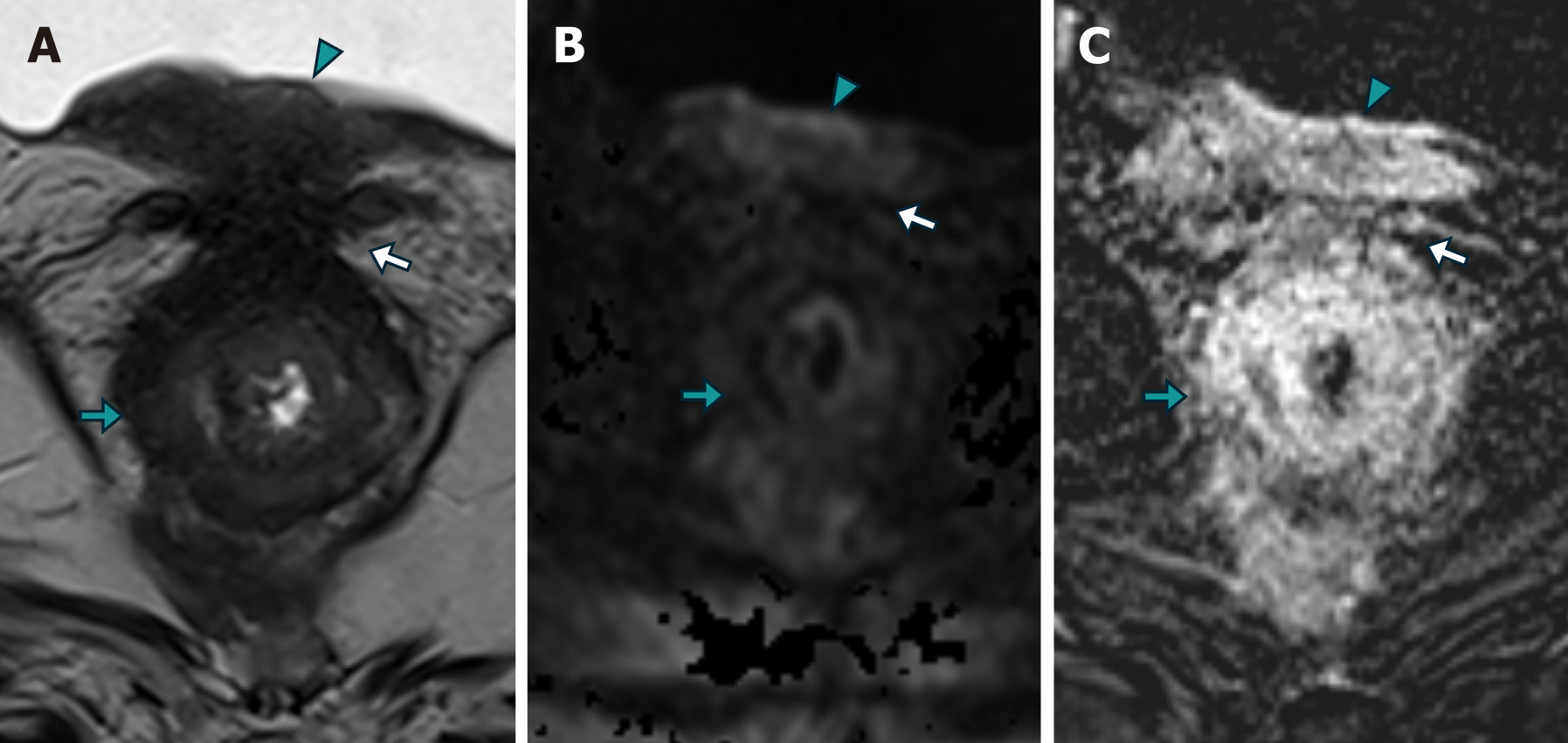

Patient 3: MRI revealed changes following radical prostatectomy, highlighting a neoplastic mass located at the vesicourethral anastomosis, infiltrating the floor of the bladder wall, and locally extending to the rectal wall with concentric neoplastic involvement suggestive of a "linitis plastica" pattern, with areas of intermediate signal intensity in the T2 sequence, restricted diffusion in DWI, and stratified enhancement in the IVC study (Figure 8).

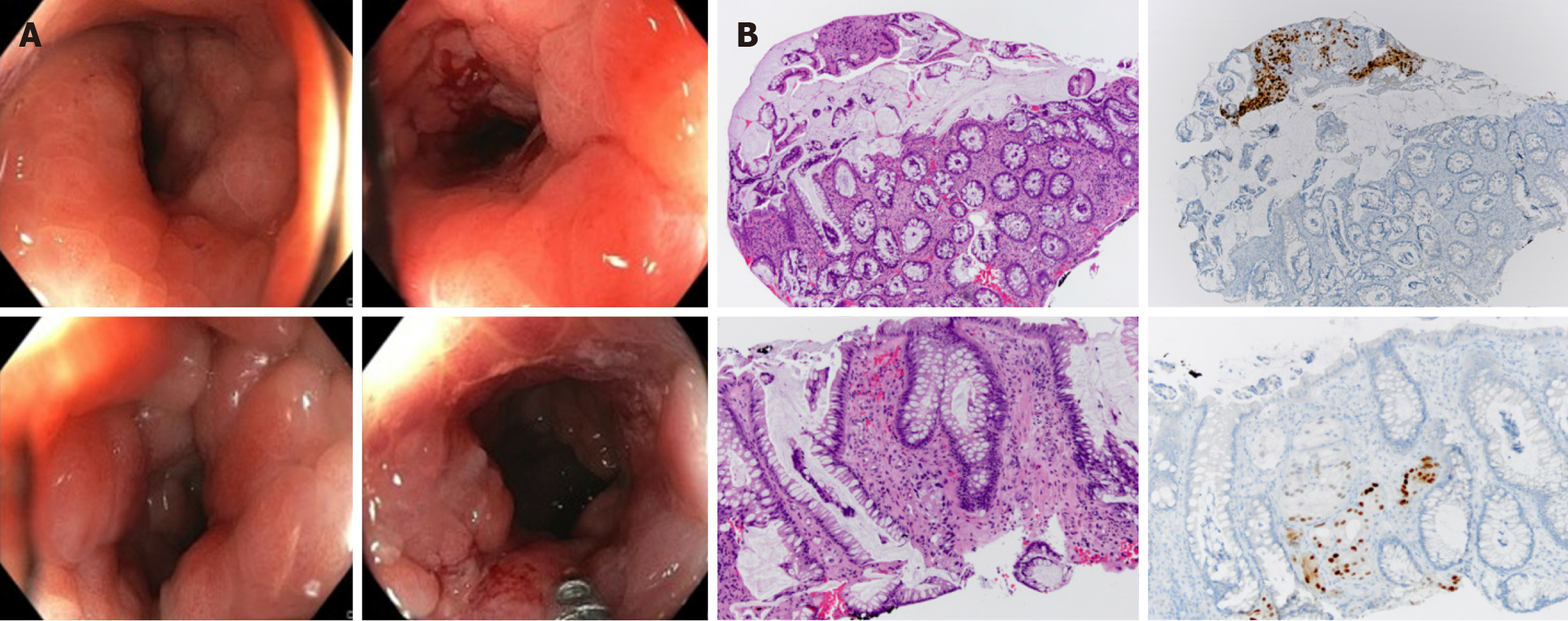

To confirm the diagnosis, a colonoscopy was performed, revealing a reduced lumen, increased consistency, and loss of parietal elasticity, as well as incipient involvement of the mucosa. Biopsies were performed, confirming neoplastic involvement of the large intestine wall due to prostatic adenocarcinoma (Figure 9).

Biopsy confirmed secondary RLP due to prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Endoscopic biopsy confirmed the presence of poorly differentiated neoplastic infiltrates compatible with prostatic origin.

The specific treatment details were not available at the time of reporting.

Outcome and follow-up details were not available at the time of reporting.

Secondary infiltration of the rectum with a "linitis plastica" pattern is uncommon, and most publications are case reports[8-10]. A pattern of concentric rings or a "bull's-eye sign" is observed in T2-, T1-, and DWI-weighted MR images, as confirmed in the presented cases. This pattern is likely caused by an exaggerated growth of normal anatomy due to the interposition of infiltrating tumor and desmoplastic tissue in the submucosa and around the muscular layer. Some authors have proposed that subserosal involvement may also exist. A consensus exists in most of the cases described in the literature that the mucosa is preserved or that its involvement is not related to the extent of parietal involvement[9-11].

Initially, this radiological pattern was considered exclusive to signet ring cell carcinoma, an advanced stage of a subtype of primary rectal adenocarcinoma[12], which is a very uncommon disease, with an incidence of < 1% among all colorectal malignancies[11,13]. However, it is now known that rectal infiltration can be secondary to metastasis from other pelvic organs, such as the prostate or bladder, and even from the metastasis of gastric, vesicle, and lobular breast carcinomas and, less frequently, to the prostate, as demonstrated in our cases[5-10]. The literature review underscores the rarity of this condition, with most reports documenting only a single case. In contrast, our study consolidates the experience of three patients who presented at our center, providing a broader perspective on the clinical and radiological characteristics of secondary RLP caused by prostatic adenocarcinoma. In our series, all patients presented concentric parietal involvement and thickening of the rectal layers, which is compatible with the findings described in the literature.

There are also nonneoplastic causes that can mimic this pattern on MRI, such as inflammatory bowel diseases, infections such as cytomegalovirus, and post-radiation pelvic proctitis. Therefore, although the concentric ring pattern is characteristic of RLP, it is not specific or sensitive and should be interpreted with caution, in accordance with the clinical and histopathological background of the patients[4].

Patients with RLP secondary to prostate cancer can present asymptomatically or may experience abdominal and/or rectal pain, alteration of the intestinal rhythm, or rectal bleeding, so the clinical presentation may be confused with digestive neoplasia and usually includes a lower digestive endoscopy. Endoscopic biopsy, which generally penetrates the mucosa and part of the submucosa, sometimes does not demonstrate the presence of malignancy because the disease usually affects the layers of the submucosa and the muscular propria with preservation of the mucosa, so a diagnostic effort must be made to search for histological confirmation[6]. An example of this is Case No. 1, where the presence of scarce malignant cells in the submucosal plane and some in the mucosal plane confirmed the diagnosis. Analyzing similar case reports, in the study by You et al[10], upon suspicion of "linitis plastica" imaging findings and an initial negative endoscopic biopsy, a full-thickness transanal excision biopsy was performed, which confirmed deep rectal involvement secondary to metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. This highlights the importance of recognizing imaging findings and an adequate interpretation of the clinical background.

The patients varied in age, presented with initial symptoms, and had general conditions. The imaging techniques and pathological findings were consistent across cases in terms of tumor characteristics; however, the extent and pattern of involvement differed. All patients were receiving treatment for prostate cancer, but specific options and management strategies differed on the basis of the stage, extent, and response to prior treatments. This variability in presentation and treatment highlights the need for a tailored approach to patient care. Additionally, the lack of detailed treatment infor

In relation to the dissemination pathways, three proposed routes exist for cases of adenocarcinoma of the prostate involving the rectum[14] (Figure 10).

Direct extension through the rectoprostatic fascia. Although Denonvilliers' fascia usually prevents the posterior extension of prostate cancer, direct dissemination may occur and is related to unresected advanced tumors. Cases 2 and 3 probably correspond to this type of dissemination.

Retrograde lymphatic/venous dissemination. Since the prostate and rectum share some drainage routes to pelvic lymph node groups and venous drainage, this may constitute the dissemination pathway for patient 1[15].

Neoplastic cells were seeded along the route of needle biopsy in the rectal wall or perirectal tissue. These cases are extremely rare and controversial[16]. However, studies that demonstrate causality are lacking.

Given the rarity of RLP as a metastatic manifestation of prostate adenocarcinoma, early and accurate identification via MRI is critical not only for distinguishing this condition from primary gastrointestinal malignancies but also for guiding treatment strategies. Recognizing characteristic imaging patterns, such as concentric wall thickening and the "target sign", enables clinicians to tailor therapeutic interventions, potentially avoiding unnecessary surgical procedures and focusing on targeted therapies. Additionally, these findings provide valuable insights into the likely disease course, allowing for a more informed prognosis. Integrating these radiological insights into a multidisciplinary approach enhances personalized care and ultimately improves outcomes for patients with this complex metastatic disease.

The study acknowledges that the limited number of cases constrains the generalizability of the findings, as the observed clinical presentations, imaging characteristics, and outcomes may not fully capture the broader spectrum of secondary RLP caused by prostatic adenocarcinoma. Additionally, the retrospective nature of the study introduces potential selection bias, as cases were identified and analyzed on the basis of available records, possibly excluding those with atypical presentations or incomplete data. Recognizing these limitations enhances the transparency of the research and underscores the need for future studies with larger cohorts and prospective designs to validate the findings and broaden our understanding of this rare metastatic condition.

As a projection for future research, it is crucial to emphasize the need for larger cohort studies with long-term follow-up of patients with prostatic neoplasia. Such studies could more accurately determine the incidence of RLP and facilitate the development of diagnostic algorithms that recognize this condition as a potential manifestation of prostate cancer dissemination MR. Research aimed at refining imaging techniques or integrating MRI with other modalities, such as PET/CT, could significantly increase diagnostic accuracy and reduce the risk of misdiagnosis. Addressing these areas in future research would build upon the valuable insights presented in this study, ultimately improving patient outcomes and advancing the management of secondary RLP in clinical practice.

Metastatic rectal neoplastic dissemination of the "linitis plastica" type is poorly understood and must be included in the dissemination forms of prostate cancer. Owing to the increasing use of MRI in monitoring rectal and prostate neoplasms, it is crucial for radiologists to be aware of and master their manifestations on MRI to perform accurate neoplastic staging. Distinguishing between primary rectal carcinoma and prostate carcinoma metastasis in the rectum is highly important because of the different treatments and prognoses involved. Proper imaging interpretation and immunohistochemical study of biopsies can prevent high-morbidity surgical interventions and direct treatments to therapies adapted to the corresponding dissemination stage.

| 1. | Fernet P, Azar HA, Stout AP. Intramural (tubal) spread of linitis plastica along the alimentary tract. Gastroenterology. 1965;48: 419-424. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Laufman H, Saphir O. Primary linitis plastica type of carcinoma of the colon. AMA Arch Surg. 1951;62:79-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ba-Ssalamah A, Prokop M, Uffmann M, Pokieser P, Teleky B, Lechner G. Dedicated multidetector CT of the stomach: spectrum of diseases. Radiographics. 2003;23:625-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mouaqit O, Mohsine R, Chenna, Ktaibi R, Sergi B, Boubouh A, El Malki O, Ifrine L, Belkouchi A. La linite plastique rectale primitive: une tumeur exceptionnelle. J Afr Cancer. 2010;2:54-56. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Liu ZH, Li C, Kang L, Zhou ZY, Situ S, Wang JP. Prostate cancer incorrectly diagnosed as a rectal tumor: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:2647-2650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dumontier I, Roseau G, Palazzo L, Barbier JP, Couturier D. Endoscopic ultrasonography in rectal linitis plastica. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:532-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Khor V, Khairul-Asri MG, Fahmy O, Hamid SA, Lee CKS. Linitis plastica of the rectum secondary to metastatic prostate cancer: A case report of a rare presentation and literature review. Urol Ann. 2021;13:442-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mommersteeg MC, Kies DA, van der Laan J, Wonders J. Linitis plastica of the rectum secondary to prostate carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schmeusser B, Wiedemer J, Fichtenbaum E. Linitis prostatica: A unique case of circumferential narrowing of the rectum. J Clin Images Med Case Rep. 2022;3:2122. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | You JH, Song JS, Jang KY, Lee MR. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings of metastatic rectal linitis plastica from prostate cancer: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2018;6:554-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rudralingam V, Dobson MJ, Pitt M, Stewart DJ, Hearn A, Susnerwala S. MR imaging of linitis plastica of the rectum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:428-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nguyen MD, Plasil B, Wen P, Frankel WL. Mucin profiles in signet-ring cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:799-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Burgain C, Germain A, Bastien C, Orry X, Choné L, Claudon M, Laurent V. Computed tomography features of gastrointestinal linitis plastica: spectrum of findings in early and delayed phase imaging. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41:1370-1377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barbosa FG, Queiroz MA, Nunes RF, Viana PCC, Marin JFG, Cerri GG, Buchpiguel CA. Revisiting Prostate Cancer Recurrence with PSMA PET: Atlas of Typical and Atypical Patterns of Spread. Radiographics. 2019;39:186-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Murray SK, Breau RH, Guha AK, Gupta R. Spread of prostate carcinoma to the perirectal lymph node basin: analysis of 112 rectal resections over a 10-year span for primary rectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1154-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vaghefi H, Magi-Galluzzi C, Klein EA. Local recurrence of prostate cancer in rectal submucosa after transrectal needle biopsy and radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2005;66:881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |