Published online Apr 26, 2010. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v2.i4.98

Revised: April 6, 2010

Accepted: April 9, 2010

Published online: April 26, 2010

AIM: To evaluate cardiac function and structure in untreated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients without clinical evidence of cardiovascular disease.

METHODS: Fifty-three naïve untreated HIV-infected patients and 56 healthy control subjects underwent clinical assessment, electrocardiography (ECG) and echocardiography, including tissue doppler imaging. Moreover, a set of laboratory parameters was obtained from all subjects, including HIV-RNA plasma levels, CD4 cell counts and tumor necrosis factor-α levels.

RESULTS: The two groups showed normal ECG traces and no differences regarding systolic morphologic parameters. In contrast, a higher prevalence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (abnormal relaxation or pseudonormal filling pattern) was found in the HIV patients (36% vs 9% in patients and controls, respectively, P <0.001).

CONCLUSION: Subclinical cardiac abnormalities appear in an early stage of the HIV infection, independent of antiretroviral therapy. The data suggest that HIV per se plays a role in the genesis of diastolic dysfunction.

- Citation: Oliviero U, Bonadies G, Bosso G, Foggia M, Apuzzi V, Cotugno M, Valvano A, Leonardi E, Borgia G, Castello G, Napoli R, Saccà L. Impaired diastolic function in naïve untreated human immunodeficiency virus infected patients. World J Cardiol 2010; 2(4): 98-103

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v2/i4/98.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v2.i4.98

The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has greatly improved the morbidity and mortality of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients[1]. However, the spectrum of cardiovascular complications occurring in HIV infection has gradually evolved from opportunistic infections, such as pericarditis, myocarditis and endocarditis, to clinical pictures of atherosclerosis such as myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular events[2,3]. Today, more than 10% of HIV patients experience cardiovascular complications that might have been prevented and require treatment[4].

Cardiovascular complications and metabolic effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy are well known[5-7]. In particular, abnormalities of vascular structure and function[8,9] and echocardiographic patterns of diastolic dysfunction[10] have been frequently reported in HIV patients treated with HAART.

An unresolved issue, however, is whether HIV plays a role in the genesis of the cardiovascular alterations. In a previous paper, we observed a reduction of brachial flow mediated dilation (FMD) and an increase of intima-media thickness (IMT) in naïve HIV patients[11], due to HIV atherogenic effects and/or the associated impairment of the immunological system.

The aim of this study was to establish whether HIV per se plays a role in the genesis of cardiac abnormalities reported in HIV infected patients. To this end, we assessed left ventricular morphology and performance in 53 HIV-positive naïve patients without clinical history and/or evidence of cardiovascular disease. Patients were consecutively referred to the infectious disease ambulatory clinic during the last year. Our study also included 56 well-matched healthy control subjects.

Fifty-three HIV-positive patients, who had never received antiviral treatment, were consecutively recruited from the ambulatory clinic of the Infectious Disease Department of the University of Naples Federico II during the last year, and 56 healthy HIV-negative control subjects recruited from university personnel, matched for age, sex, body mass index, and cigarette smoking characteristics, were enrolled in the study.

Exclusion criteria were: co-infection with hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus, recent opportunistic infection, history of major cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack or stroke), arterial hypertension, use of lipid-lowering agents, glycemia > 100 mg/dL, body mass index > 25 kg/m2 and renal or liver disease. These criteria were chosen to exclude patients with a history of cardiovascular disease. No patient was taking anti-hypertensive or antiplatelet drugs. Clinical assessment of the subjects included physical examination and 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG).

All participants gave their informed written consent and the protocol was approved by the University of Naples Federico II Ethics Committee.

Total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, homocysteine, and C-reactive protein values were determined using standard laboratory procedures. HIV-RNA plasma levels (copies/mL) were determined by ultrasensitive assay (Roche diagnostics). CD4 cell counts were determined by flow cytometry. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α assays were performed by a chemiluminescent enzyme immunometric method.

Echocardiography was performed in each subject according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography[12]. An ultrasound system equipped with a 2.5 MHz multifrequency transducer (Aplio XG imaging system, Toshiba, Japan) was used for complete M-mode, two-dimensional, doppler and tissue doppler imaging (TDI) echocardiographic analyses. Electrocardiographic leads were connected and patients were laid in the left lateral position and examined in standard parasternal long and short axis and apical views. Data were recorded digitally for further blinded offline analysis. Measurements were based on the average of three cardiac cycles. Global intra- and interobserver coefficients of variation were < 7%. A blinded investigator (U.O.) read the echoes offline.

M-mode and two-dimensional measures of left ventricular (LV) architecture were assessed according to standard formulae. The methods are described in detail elsewhere[13]. The following systolic parameters were measured: LV diameters in end diastole and end systole, interventricular septum and LV posterior wall thickness in diastole and systole. LV ejection fractions were assessed using Simpson’s biplane rule using conventional apical four- and two-chamber views.

Diastolic function indices were first analyzed by pulsed doppler recordings, with the sample volume located between the tips of the mitral leaflets. The following parameters of diastolic function were measured: peak velocity of early (E wave) and late (A wave) mitral outflow and the E/A ratio, mitral deceleration time (Dct), and the isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT) defined as the time interval between aortic valve closure and mitral valve opening.

Quantitative diastolic data were derived from TDI analysis. The sample volume (4 mm3) was placed in the left ventricular basal portions of the septal and lateral walls (using the four chambers images) and each parameter was calculated as the mean of both measures. The following parameters were derived: early (Em) and late (Am) diastolic velocities and the Em/Am ratio. The combined index E/Em ratio, a method of estimating LV filling pressures[14], was also calculated.

The data are expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons of echocardiographic and TDI parameters between HIV patients and controls were performed by the unpaired Student’s t-test. Pearson’s correlation was used when appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

The two groups (HIV patients and control subjects) were similar in terms of sex, age, and body mass index. Blood pressure levels, metabolic parameters and biomarkers were comparable in the two groups (Table 1). Physical examination did not show any alteration and electrocardiographic data were in the normal range in all subjects.

| HIV patients (n = 53) | Control subjects (n = 56) | |

| Sex (M/F) | 36/17 | 38/18 |

| Age (yr) | 38 ± 7 | 39 ± 8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 |

| Current smoking (%) | 38 | 36 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 128 ± 5 | 120 ± 9 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 78 ± 3 | 76 ± 7 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 158 ± 27 | 160 ± 33 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 44 ± 4 | 45 ± 6 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 127 ± 45 | 125 ± 40 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 80 ± 14 | 82 ± 13 |

| Homocysteine (mg/dL) | 11.5 ± 5.1 | 8.1 ± 4.3 |

| High-sensitivity C reactive protein (mg/L) | 0.68 ± 0.79 | 0.47 ± 0.35 |

The viral load, the duration of infection, the immunological data and the cytokine TNF-α mean values are reported in Table 2. The duration from HIV-infection and study enrollment was 29.7 ± 28.0 mo. We did not detect patients who remained untreated for more than 5 years after HIV infection. As shown in Table 2, a significant difference was observed between the TNF-α values in HIV patients and controls (P < 0.001).

| HIV patients (n = 53) | Control subjects (n = 56) | |

| HIV-RNA (copies/mL) | 9.754 ± 13.172 | |

| Duration of HIV infection (mo) | 29.7 ± 28.0 | |

| CD4+ (cells/mm3) | 370 ± 295 | |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 18 ± 9b | 8 ± 6 |

The LV ejection fraction was in the normal range both in HIV patients and controls. No differences regarding systolic morphologic parameters were found between the two groups (Table 3).

| HIV patients (n = 53) | Control subjects (n = 56) | |

| M-mode measurements | ||

| LV-ED dimension (mm) | 45.6 ± 5.9 | 46.2 ± 5.1 |

| LV-ES dimension (mm) | 31.1 ± 5.9 | 30.7 ± 6.5 |

| LV-IS diastole (mm) | 10.30 ± 2.03 | 9.90 ± 3.30 |

| LV-IS systole (mm) | 13.20 ± 2.85 | 13.10 ± 3.20 |

| LV-PW diastole (mm) | 9.06 ± 2.30 | 9.30 ± 2.50 |

| LV-PW systole (mm) | 12.9 ± 2.7 | 11.8 ± 3.1 |

| B-mode measurements | ||

| EDV (mL) | 107.6 ± 29.9 | 110.0 ± 33.6 |

| ESV (mL) | 44.2 ± 16.5 | 42.0 ± 17.1 |

| LV-EF ( biplane Simpson's) (%) | 63.3 ± 7.1 | 65.1 ± 8.2 |

| SV (mL) | 26.0 ± 20.8 | 24.6 ± 18.9 |

| LV-ET (ms) | 308.0 ± 40.8 | 306.0 ± 41.2 |

Data of diastolic function are reported in Table 4. HIV patients with an E/A ratio < 1 were considered to have an abnormal relaxation pattern. Patients with an E/A ratio > 1, and a TDI diastolic parameter Em/Am < 1, were considered to have a pseudonormal relaxation pattern. An abnormal relaxation pattern was detected in 16 patients (30%) and 4 controls (7%). Using TDI findings in subjects with an E/A ratio > 1, pseudonormalized flow patterns were observed in 3 more patients (6% of HIV patients) and in 1 control subject (2%). Taken together, 36% of the HIV patients showed an altered diastolic filling pattern (abnormal relaxation or pseudonormal filling) compared with 9% in the control group (P < 0.001).

| HIV patients(n = 53) | Control subjects (n = 56) | P | |

| Transmitralic Doppler | |||

| Peak E wave velocity (cm/s) | 62.7 ± 18.3 | 79.1 ± 16.4 | < 0.001 |

| Peak A wave velocity (cm/s) | 57.8 ± 15.7 | 65.5 ± 21.1 | < 0.050 |

| E/A ratio | 1.11 ± 0.26 | 1.25 ± 0.20 | < 0.001 |

| Dct (ms) | 190.7 ± 24.8 | 178.1 ± 26.5 | < 0.050 |

| IVRT (ms) | 98.1 ± 14.3 | 86.9 ± 14.4 | < 0.010 |

| Tissue Doppler | |||

| Peak Em wave velocity (cm/s) | 12.7 ± 8.2 | 18.9 ± 5.6 | < 0.001 |

| Peak Am wave velocity (cm/s) | 10.0 ± 6.9 | 14.3 ± 4.9 | < 0.001 |

| Em/Am ratio | 1.18 ± 0.36 | 1.36 ± 0.24 | < 0.010 |

| Combined index | |||

| E/Em ratio | 6.6 ± 3.5 | 4.5 ± 1.9 | < 0.001 |

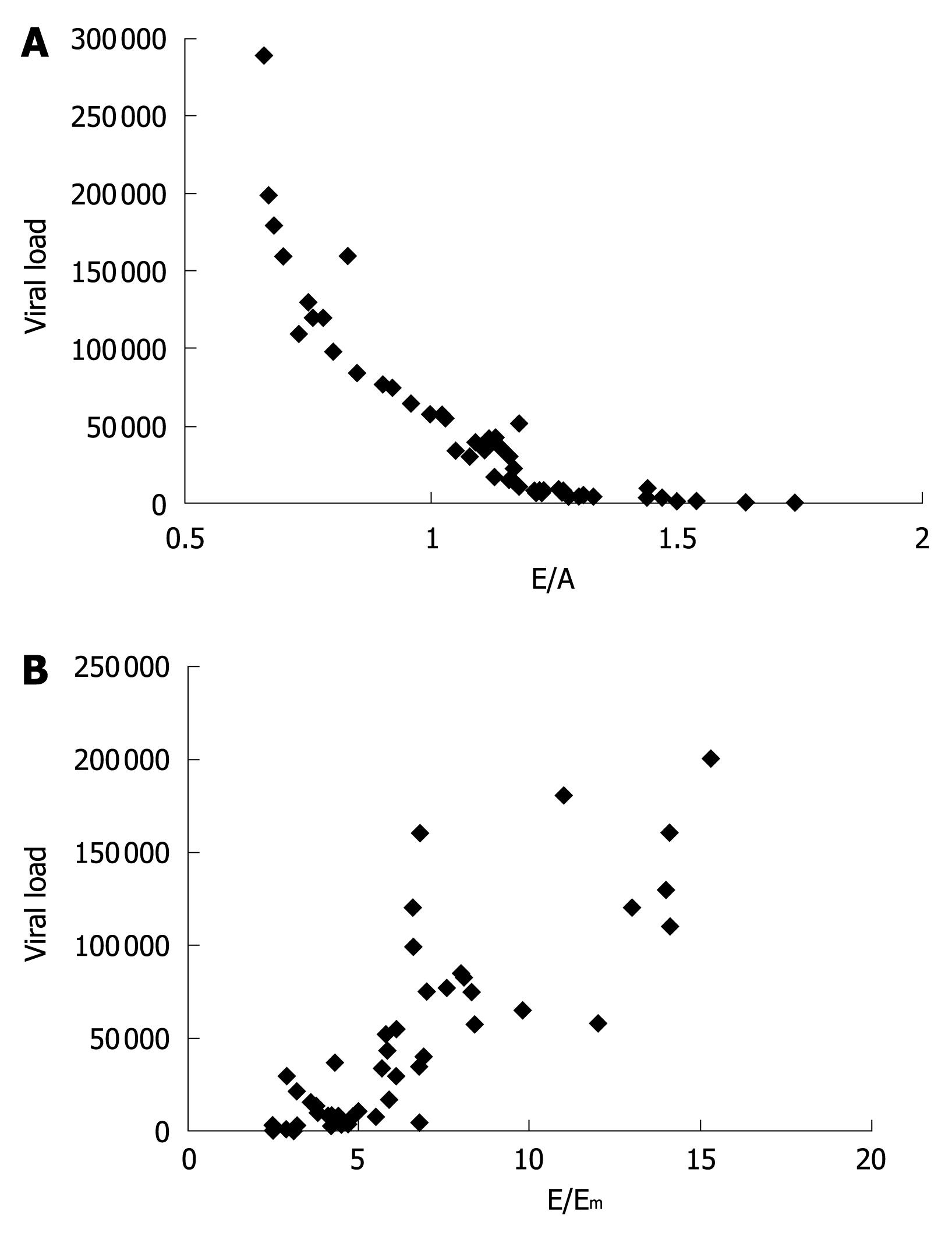

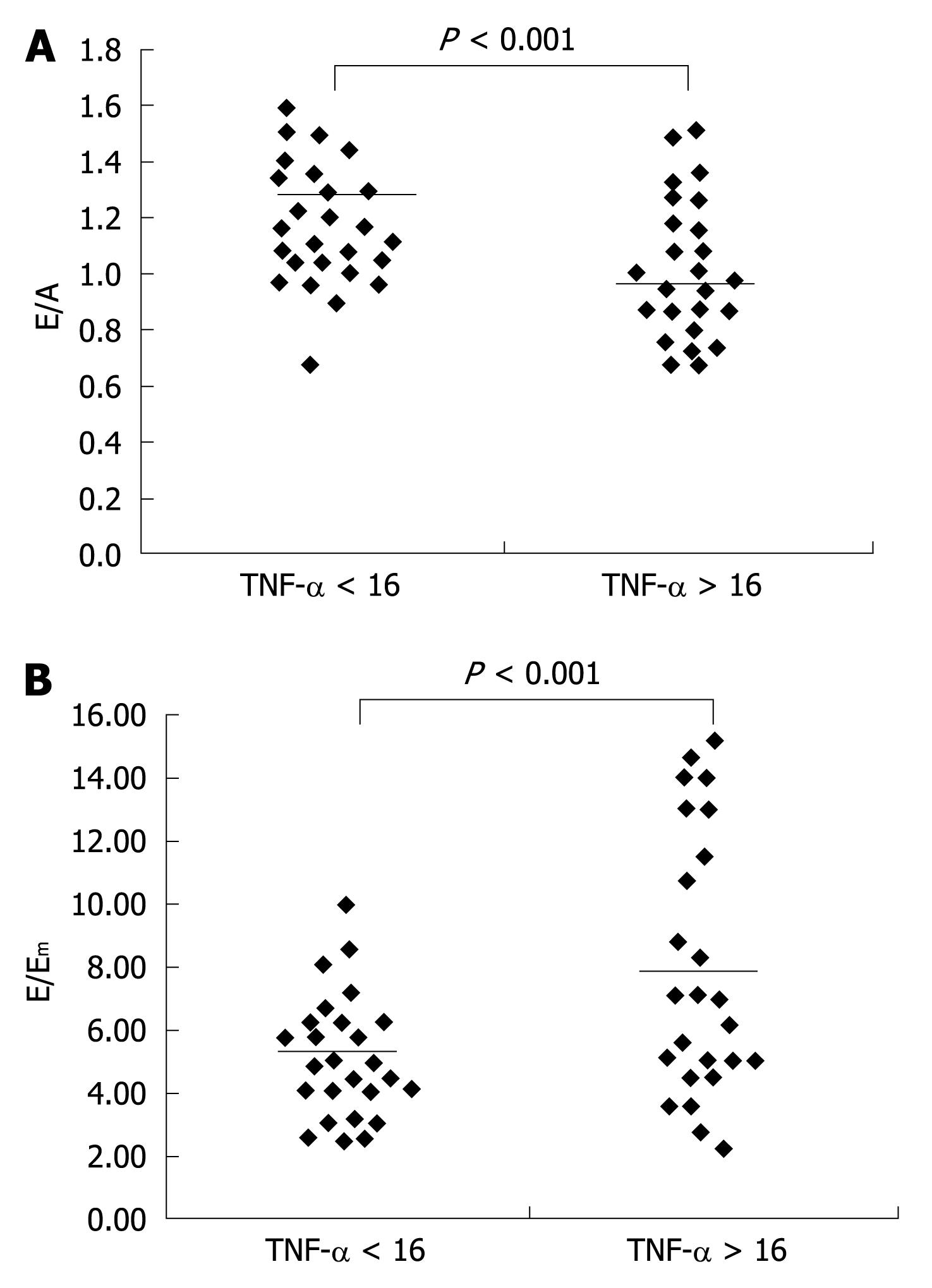

Among all altered diastolic parameters, the E/A ratio (r = -0.84, Figure 1A) and the combined index E/Em (r = 0.83, Figure 1B) were strongly correlated with viral loads. We next analyzed the diastolic data in HIV naïve patients in relation to the circulating levels of TNF-α, using a cut-off value corresponding to the upper limits of the physiologic range of the cytokine in our healthy population (16 pg/mL). The HIV patients with TNF-α levels > 16 pg/mL showed lower E/A (P < 0.001, Figure 2A) and higher E/Em (P < 0.001, Figure 2B) indexes.

In a previous paper, we observed early vascular abnormalities in naïve untreated HIV-infected patients[11].

The aim of this study was to characterize the diastolic function in naïve untreated HIV-infected patients, consecutively referred during the last year to the Ambulatory Clinic of Infectious Disease.

The appearance of abnormalities in diastolic function certainly plays an important role in the increase of the cardiovascular risk in HIV treated patients. Schuster et al[15] observed a high prevalence (64%) of diastolic dysfunction in a cohort of HIV-positive patients receiving HAART for > 2 years with no clinical evidence of cardiovascular disease. However, it has proven difficult to distinguish the relative importance of the main potential players; i.e. HIV infection itself, HAART, and the metabolic abnormalities that often cluster with HIV infection.

In this paper, we present the first evidence of diastolic dysfunction in HIV-infected patients who have never received antiretroviral treatment. Because of our exclusion criteria, the metabolic parameters of the HIV patients were within normal ranges and were very similar to the control values. Thus, our results suggest that HIV per se can trigger mechanisms that lead to diastolic dysfunction at an early stage of the infection.

HIV may impair diastolic function by inducing abnormalities of both cardiomyocytes and myofibrils with a consequent increase of cardiac stiffness. Indeed, Pozzan et al[16] showed cardiac alterations in 83% of untreated AIDS patients’ necropsies. In particular, these authors detected cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ultrastructural damage, such as mithocondriosis with increased dense bodies, increased lipofuscin pigment granules, and reduction and disarray of myocardial myofibrils.

Moreover, HIV may determine diastolic dysfunction through the inflammatory and immunological responses caused by the infection and related to the viral load.

In our study, in fact, we observed a clear correlation between both the E/A ratio and E/Em ratio with the HIV-RNA copy number, suggesting that the viral load plays a role in the genesis of cardiac alterations.

Monsuez et al[17] reported cardiac involvement with cardiomyocyte apoptosis and an increase of connective trabeculae in the course of HIV infection primarily due to proinflammatory cytokines.

We also detected elevated plasma levels of TNF-α in our HIV infected patients and the levels of TNF-α were directly correlated with plasma HIV-RNA copies. Moreover, the diastolic indexes E/A and E/Em were more often altered in HIV patients with increased TNF-α values, and high levels of TNF-α have been reported in patients with coronary artery disease who showed diastolic dysfunction but preserved systolic function[18].

In conclusion, our data support the hypothesis that HIV per se can play a role in the genesis of diastolic dysfunction detected in our patients from an early stage of the infection.

The major limitation of the study is represented by the absence of structural findings in our “naïve patients”, such as histological samples of cardiomyocytes infected by HIV. For these reasons, the relation between the diastolic dysfunction observed in our patients and HIV infection must be considered a strong association, but not a clear cause-effect relationship. Further studies with possible tissue analysis and findings suggestive of HIV infection derived from the cardiac muscle before starting HAART protocols are needed to confirm the hypothesis that HIV is responsible for the genesis of the impairment of the cardiac diastolic indexes.

However, cardiovascular risk assessment and regular cardiovascular evaluation, including echocardiography, should be considered in HIV infected patients from the beginning of the disease. The early detection of cardiovascular involvement might be useful in order to start a program of preventive medicine as soon as possible, which should be instituted even if the clinical relevance of early diastolic dysfunction and the eventual progression to diastolic heart failure or HIV cardiomyopathy have not been completely clarified. This program should primarily include the treatment of coexisting risk factors (e.g. diabetes, hypertension and dislipidemia) and lifestyle interventions, restricting pharmacologic treatments to selected cases with early signs of diastolic heart failure[19].

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients treated with the new antiretroviral agents [Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)] showed a major incidence of cardiovascular events as myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. These complications have been related to the metabolic effects of HAART regimens. However, the authors have often detected early cardiovascular alterations in untreated HIV infected subjects. For this reason they hypothesized that HIV per se can play a role in the genesis of the cardiac abnormalities frequently detected during the course of the infectious disease. To support the authors' hypothesis, they evaluated fifty three naïve untreated HIV patients without clinical history and/or evidence of cardiovascular disease and observed a significant increase of echocardiographic signs of diastolic dysfunction as compared with 56 healthy HIV-negative control subjects recruited from the university personnel.

HIV plays a role in the genesis of cardiac abnormalities through the inflammatory and immunological responses caused by infection and related to the viral load. The data lend support to the viral infectious theory of atherosclerosis, even if the association between HIV infection and appearance of cardiovascular abnormalities need to be confirmed by further studies with tissue analysis and findings suggestive of HIV infections in cardiac muscle.

The widespread use of the new antiretroviral agents (HAART) has been associated with the major incidence of cardiovascular events detected in HIV treated patients. In this study, the authors present the first evidence of diastolic dysfunction in HIV-infected patients who have never received antiretroviral treatment. Due to the exclusion criteria adopted, the metabolic parameters of the HIV patients were within normal range and very similar to the control values. Thus, the results suggest that HIV per se can trigger mechanisms that lead to diastolic dysfunction at an early stage of the infection.

Two are the major implications of the study: (1) HIV contributes to the cardiac abnormalities through the inflammatory and immunological responses caused by infection and related to the viral load. Other infections caused by different viruses with the same mechanisms of action might be complicated by the appearance of similar early atherosclerotic lesions; and (2) Echocardiographic assessment should be considered in HIV infected patients from the early stages of the disease for starting a program of preventive medicine as soon as possible.

This study showed a possibility that HIV infection per se induces diastolic dysfunction, which may be caused by proinflammatory cytokine-mediated structural damage in the heart. The data were well-presented, and the conclusions were properly conducted. It will be a great article as start off point and it needs further sudies with possible tissue analysis and findings suggestive of HIV infection in the cardiac muscle will be more helpful.

Peer reviewers: Shinji Satoh, MD, PhD, Department of Cardiology and Clinical Research Institute, National Hospital Organization Kyushu Medical Center, 1-8-1 Jigyohama, Chuo-ku, Fukuoka 810-8563, Japan; Antony Leslie Innasimuthu, MD, MRCP, Presbyterian-Shadyside Program, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, 5230 Center Ave, Pittsburgh, PA 15232, United States

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Lutze M E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Palella FJ Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, Aschman DJ, Holmberg SD. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853-860. |

| 2. | Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2506-2512. |

| 3. | Bozzette SA, Ake CF, Tam HK, Chang SW, Louis TA. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in patients treated for human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:702-710. |

| 4. | Monsuez JJ, Charniot JC, Escaut L, Teicher E, Wyplosz B, Couzigou C, Vignat N, Vittecoq D. HIV-associated vascular diseases: structural and functional changes, clinical implications. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133:293-306. |

| 5. | Friis-Møller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, Weber R, Monforte A, El-Sadr W, Thiébaut R, De Wit S, Kirk O, Fontas E. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1723-1735. |

| 6. | Carr A. Cardiovascular risk factors in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34 Suppl 1:S73-S78. |

| 7. | Stein JH. Cardiovascular risks of antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1773-1775. |

| 8. | Stein JH, Klein MA, Bellehumeur JL, McBride PE, Wiebe DA, Otvos JD, Sosman JM. Use of human immunodeficiency virus-1 protease inhibitors is associated with atherogenic lipoprotein changes and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2001;104:257-262. |

| 9. | Sankatsing RR, Wit FW, Vogel M, de Groot E, Brinkman K, Rockstroh JK, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES, Reiss P. Increased carotid intima-media thickness in HIV patients treated with protease inhibitors as compared to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Atherosclerosis. 2009;202:589-595. |

| 10. | Thöni GJ, Schuster I, Walther G, Nottin S, Vinet A, Boccara F, Mauboussin JM, Rouanet I, Edérhy S, Dauzat M. Silent cardiac dysfunction and exercise intolerance in HIV+ men receiving combined antiretroviral therapies. AIDS. 2008;22:2537-2540. |

| 11. | Oliviero U, Bonadies G, Apuzzi V, Foggia M, Bosso G, Nappa S, Valvano A, Leonardi E, Borgia G, Castello G. Human immunodeficiency virus per se exerts atherogenic effects. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:586-589. |

| 12. | Quiñones MA, Otto CM, Stoddard M, Waggoner A, Zoghbi WA. Recommendations for quantification of Doppler echocardiography: a report from the Doppler Quantification Task Force of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:167-184. |

| 13. | Salerno M, Oliviero U, Lettiero T, Guardasole V, Mattiacci DM, Saldamarco L, Capalbo D, Lucariello A, Saccà L, Cittadini A. Long-term cardiovascular effects of levothyroxine therapy in young adults with congenital hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2486-2491. |

| 14. | Dokainish H, Zoghbi WA, Lakkis NM, Al-Bakshy F, Dhir M, Quinones MA, Nagueh SF. Optimal noninvasive assessment of left ventricular filling pressures: a comparison of tissue Doppler echocardiography and B-type natriuretic peptide in patients with pulmonary artery catheters. Circulation. 2004;109:2432-2439. |

| 15. | Schuster I, Thöni GJ, Edérhy S, Walther G, Nottin S, Vinet A, Boccara F, Khireddine M, Girard PM, Mauboussin JM. Subclinical cardiac abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men receiving antiretroviral therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1213-1217. |

| 16. | Pozzan G, Pagliari C, Tuon FF, Takakura CF, Kauffman MR, Duarte MI. Diffuse-regressive alterations and apoptosis of myocytes: possible causes of myocardial dysfunction in HIV-related cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132:90-95. |

| 17. | Monsuez JJ, Escaut L, Teicher E, Charniot JC, Vittecoq D. Cytokines in HIV-associated cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2007;120:150-157. |

| 18. | Kosmala W, Derzhko R, Przewlocka-Kosmala M, Orda A, Mazurek W. Plasma levels of TNF-alpha, IL-6, and IL-10 and their relationship with left ventricular diastolic function in patients with stable angina pectoris and preserved left ventricular systolic performance. Coron Artery Dis. 2008;19:375-382. |

| 19. | Hogg K, McMurray J. The treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction ("diastolic heart failure"). Heart Fail Rev. 2006;11:141-146. |