Published online Mar 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i3.103947

Revised: January 22, 2025

Accepted: February 10, 2025

Published online: March 26, 2025

Processing time: 106 Days and 16 Hours

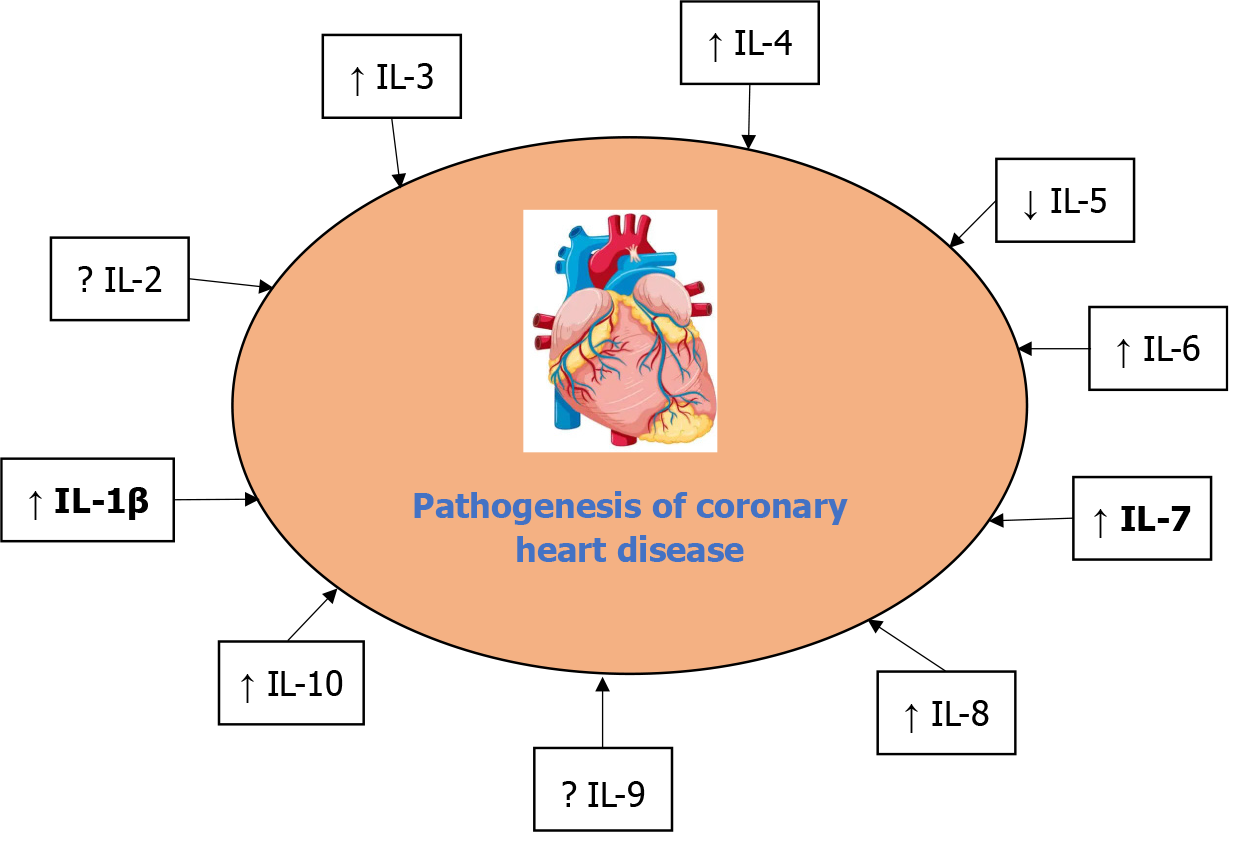

Interleukins (ILs), a subset of cytokines, play a critical role in the pathogenesis of coronary heart disease (CHD) by mediating inflammation. This review article summarizes the role of ILs such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, and IL-10 in the pathogenesis of CHD. Individuals with mild coronary artery disease (CAD) and angina who have ischemic heart disease have higher serum concentrations of IL-1b. Larger studies are needed to verify the safety and assess the effectiveness of low-dose IL-2 as an anti-inflammatory treatment. IL-3 is found more often in patients receiving coronary angioplasty compared to patients with asymptomatic CAD or without CAD. Serum levels of IL-4 are reliable indicators of CAD. An independent correlation between IL-5 and the incidence of CAD was demonstrated. IL-6 helps serve as a reliable biomarker for the degree of CAD, as determined by the Gensini score, and is a key factor in the development of atherosclerosis. Also, variants of IL-7/7R have been linked to the Han Chinese popu

Core Tip: Cytokines play a role in the development of coronary heart disease (CHD). Interleukins (ILs) are integral to the pathogenesis of CHD through their roles in promoting inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, plaque formation, and thrombosis. The review reports the role of ILs such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, and IL-10 in the pathogenesis of CHD and therapeutic strategies, identifies knowledge gaps, and highlights future research directions to improve the understanding and management of CHD.

- Citation: Rafaqat S, Azam A, Hafeez R, Faseeh H, Tariq M, Asif M, Arshad A, Noshair I. Role of interleukins in the pathogenesis of coronary heart disease: A literature review. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(3): 103947

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i3/103947.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i3.103947

Heart disease occurs when the heart's arteries are unable to pump enough oxygen-rich blood to the heart; this condition is known as coronary heart disease (CHD). It is also known as ischemic heart disease (IHD) or coronary artery disease (CAD). CHD is a chronic inflammatory disorder marked by the buildup of fatty deposits in the coronary arteries and a major cause of mortality worldwide. The incidence of CAD has been growing continuously despite improvements in therapy that have reduced the death rates from CAD[1,2].

Whereas atherosclerosis is characterized by the buildup of plaques (fat, cholesterol, calcium, and other substances) in the walls of arteries throughout the body, this process leads to the narrowing and hardening of arteries, impairing blood flow. Atherosclerosis begins with endothelial dysfunction, followed by lipid accumulation, inflammation, and plaque formation. If atherosclerosis is left untreated, it can worsen artery blockage, which can result in IHD and myocardial infarction (MI). CHD is caused directly by atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries. The pathophysiology of atherosclerosis is significantly influenced by inflammation, which is mediated by a variety of proinflammatory cytokines. Cytokines that mediate inflammation have also been linked to different phases of atherosclerosis development. Therefore, determining CAD predictors is essential for early CHD diagnosis and therapy[3,4].

A cellular and humoral reaction to viral or noninfectious harm is commonly referred to as inflammation. Even though inflammatory responses are essential for preventing infection and being vigilant against malignancy, excessive or dysregulated inflammation plays a role in the etiology of many acute and chronic illnesses. Signaling proteins called cytokines, also known as interleukins (ILs), communicate pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signals to control the inflammatory response[5].

ILs play a critical role in controlling immune responses in infectious illnesses. While anti-inflammatory ILs aid in the suppression of excessive inflammation and the promotion of tissue healing, pro-inflammatory ILs aid in the activation and recruitment of immune cells. The complex and ever-changing process of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory ILs crosstalk affects immunological responses and immune homeostasis. A thorough investigation has highlighted the complex interactions among these ILs, offering valuable perspectives on their regulation processes and prospective applications in medicine. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-1β, and IL-6 are pro-inflammatory ILs that play a crucial role in triggering and intensifying immune responses during tissue damage or infection. They encourage the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and immune cell activation. Anti-inflammatory ILs, such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, are essential regulators that balance pro-inflammatory signals and help inflammation resolve[6].

Inflammation is a key driver of CHD pathogenesis, influencing every stage from endothelial dysfunction to acute coronary events. Proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), and TNF-α, have been linked to the development of CAD[7]. Kaptoge et al[8] reported the associations of several pro-inflammatory cytokines and CHD risk in a new prospective study, including a meta-analysis of prospective studies, because low-grade inflammation may be involved in the pathogenesis of CHD and pro-inflammatory cytokines govern inflammatory cascades. Several distinct pro-inflammatory cytokines are roughly log-linearly correlated with the risk of CHD, even in the absence of traditional risk factors. The results support the concept that vascular disease is caused by inflammation, but further research is required to determine causality[8].

Another study demonstrated a substantial difference in the levels of IL-4, IL-12p70, IL-17, IFN-α, and IFN-γ between the CAD and non-CAD groups. Three risk variables (diabetes, smoking, and sex), one protective factor (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C]), and two serum cytokines (IL-4 and IL-17) were found to be independently predictive of CAD by multivariate logistic regression analysis. An area under the curve value of 0.826 indicates that the combined use of these predictors in a multivariate model indicated strong predictive ability for CAD, according to the study of the receiver operating characteristic curve[9].

Understanding inflammatory mechanisms opens avenues for novel biomarkers and targeted therapies to prevent and treat CHD. Although acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and stable CAD differ in some cytokine patterns, chronic inflammation is a key factor in CAD. Another study observed the cytokine variations between these two CAD symptoms. It comprised 308 individuals with hemodynamically severe CAD that was identified by angiography: A total of 150 patients had ACS angiography, while 158 individuals had stable CAD angiography. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), macro

Many studies have reported that cytokines play a significant role in the development of CHD. This review reports the role of ILs such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, and IL-10 in the pathogenesis of CHD as explained in Figure 1 and Table 1; reports therapeutic strategies; identifies knowledge gaps; and highlights future research directions to improve the understanding and management of CHD.

| Interleukins | Origin/source | Functions | Pathophysiological aspects | Ref. |

| IL-1 | Monocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, fibroblasts | Lymphocyte activation, fever, regulates sleep, pro-inflammatory cytokine, maturation and proliferation | It has been shown that chronic administration of IL-1β to the myocardial and coronary arteries causes cardiac dysfunction and coronary arteriosclerosis. Pericardial IL-1β concentrations could indicate the degree of ischemic heart disease, and high levels of IL-1β in pericardial fluid might also directly encourage the development of coronary atherosclerosis. It was shown that the adventitial vessel walls of atherosclerotic coronary arteries had higher levels of IL-1β protein than coronary arteries from non-ischemic cardiomyopathic hearts. This rise correlated directly with the degree of coronary atherosclerosis | [13,14] |

| IL-2 | Th1 cells | Stimulates growth of T cells | Not determined | |

| IL-3 | Th cells and mast cells | Stimulates bone marrow growth | Patients with CAD, especially those who are symptomatic and receiving percutaneous coronary intervention, have higher levels of IL-3, a key regulator of chronic inflammation. Moreover, a correlation between symptomatic restenosis and elevated IL-3 concentrations was discovered | [23] |

| IL-4 | Th2 cells, basophils, NKT cells | B-cell growth factor, role in tissue adhesion and inflammation | Serum IL-4 levels are reliable indicators of CAD | [19] |

| IL-5 | T cells | Activated T cells, Differentiation and function of myeloid cells | In the coronary plaque of CAD patients, IL-5 was substantially lower than in the group of deceased donors. The coronary artery plaque’s macrophages were the primary source of IL-5. Stable angina pectoris, unstable angina pectoris, and acute myocardial infarction were the sequences from high to low plasma IL-5 levels in the CAD groups, which were considerably lower than those in the non-CAD group. The results of binary linear regression analysis indicated an independent correlation between IL-5 and the incidence of CAD. Th1 and Th17 levels and the mRNA expression of their distinctive cytokines were reduced in CD4+Th cells treated with oxidized low-density lipoprotein after being treated with recombinant mouse IL-5. Near the IL-5 locus, genetic polymorphisms were shown to be strongly linked to coronary artery disease | [25,29] |

| IL-6 | Monocytes, macrophages, | Activated T cells, contributes to host defense through the stimulation of acute phase responses, hematopoiesis | IL-6 helps serve as a reliable biomarker for the degree of CAD as determined by the Gensini score and it is a key factor in the development of atherosclerosis. IL-6 may be a useful marker for assessing the degree of necrosis | [31] |

| IL-7 | Monocytes, macrophages, epithelial cells | T-cell development, survival and homeostasis of mature T cells, B cells and T-cell proliferation | One important factor contributing to the elevated IL-7 levels in angina patients seems to be increased release from activated platelets. Based on interactions between platelets, monocytes, and chemokines, the data point to a role for IL-7-driven inflammation in atherogenesis and the enhancement of clinical instability in CAD | [39] |

| IL-8 | Monocytes and fibroblasts | Angiogenesis, induces chemotaxis, stimulates phagocytosis, neutrophil chemotaxis, superoxide release and granule release | The expression of IL-8 mRNA or plasma IL-8 showed a strong negative connection with the development of CHD. IL-8 plays a part in the progression of CAD occurrences | [42,44] |

| IL-9 | Eosinophils, mast cells | Chemokine, Mast and T-cell growth factor and enhances T-cell survival, mast cell activation and synergy with erythropoietin | IL-9 may interact with established CAD risk factors to cause CAD | [48] |

| IL-10 | Macrophages, T cells, B cells, dendritic cells | Immune suppressed | IL-10 indicates a proinflammatory state in acute coronary syndrome patients. As a result, IL-10 is a biomarker as useful as other systemic inflammation markers for predicting the risk of future cardiovascular events | [53] |

According to the literature, there are various ILs; however, this review article summarizes the role of ILs such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, and IL-10 in the pathogenesis of CHD as explained in Figure 1, Table 1, and Table 2. The literature was searched until January 17, 2025, using several databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, and Science Direct. Keywords such as “coronary heart disease,” “ILs,” “inflammation,” and “pathogenesis” were used. Only English-language clinical research was taken into account. While preference was given to papers published recently, there was no strict timeframe for publication dates. The inclusion criteria encompassed peer-reviewed studies (clinical trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or experimental studies) examining ILs in CHD. Conversely, the excluded criteria pertained to studies that specifically address different cardiovascular diseases (CVDs).

| Interleukins | Summary of therapeutic strategies | Ref. |

| IL-1 | It suggested that IL-1 and associated cytokines could be therapeutic targets for both stable and unstable CAD. Statins' capacity to alter this system in an anti-inflammatory manner emphasizes their potential for immunomodulation. Commonly used medicinal compounds or specific molecules with focused anti-inflammatory effects can target these molecules. Together with newer treatments like TNF-α inhibitors and IL-1 receptor antagonists, the most important anti-inflammatory medications include aspirin, statins, colchicine, IL-1β inhibitors, and IL-6 inhibitors. Because of their pleiotropic and anti-inflammatory properties, aspirin and statins are well-established treatments for atherosclerosis and CAD. Identifying patients with high inflammatory profiles (e.g., elevated IL-1β or hsCRP levels) could help tailor anti-inflammatory interventions. Investigating the roles of IL-1α and IL-1 receptor antagonists in CHD could further refine therapeutic strategies | [18,73] |

| IL-2 | Immune tolerance is induced and immunological homeostasis is maintained by regulatory T cells. Low-dose IL-2 may be able to boost the number of Treg cells, according to recent in vivo research. Human recombinant IL-2, known as aldesleukin, has been utilized therapeutically to treat several autoimmune disorders. For individuals with ischemic heart disease, larger studies are required to verify the safety and assess the effectiveness of low-dose IL-2 as an anti-inflammatory treatment | [21,22] |

| IL-3 | Not determined | |

| IL-4 | Not determined | |

| IL-5 | The atheroprotective effects of IL-5 in atherosclerosis have been demonstrated to include promoting B-1 cell differentiation to release more T15/EO6 antibodies, which can inhibit macrophage absorption of oxidized low-density lipoprotein and decrease the production of foam cells. Understanding its complex contributions to immune and vascular processes could lead to new insights and therapeutic strategies for reducing CHD risk and improving cardiovascular outcomes | [27] |

| IL-6 | It revealed that although the IL-6 signaling cascade and the anti-inflammatory effect of HMG-CoA reductase were found to influence the risk of CAD. The anti-CAD effect of statins may rely on inflammatory pathways other than the IL-6 signaling cascade. The authors examined the effectiveness and current uncertainties of colchicine, IL-6 receptor antagonists, and IL-1β antibodies in the anti-inflammatory management of coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. Previous studies have indicated that rosuvastatin inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase and NF-κB to reduce the inflammatory response. Additionally, adhesion molecules and some cytokines, including IL-8, IL-6, and MCP-1, have been discovered to be decreased by it | [32,73,66] |

| IL-7 | Aspirin was given to healthy control volunteers for seven days at a dose of 160 mg per day, and it decreased the levels of IL-7 in their plasma. It also decreased the release of IL-7 from platelets both spontaneously and in response to SFLLRN stimulation. Blocking IL-7 or its IL-7R may reduce T-cell-mediated inflammation and slow atherosclerosis progression. IL-7R inhibitors are under investigation for autoimmune diseases and could be repurposed for CHD | [39] |

| IL-8 | Patients with CHD who had been taking statins continuously showed a substantial reduction in both transcriptomic and phenotypic IL-8 expression when compared to the H and N group individuals. Consequently, IL-8 need to function as a practical marker and be employed to assess the therapeutic benefits of statins as well as to depict the pathophysiology of CHD therapy. Coronary atherosclerotic plaques are reduced, vascular inflammation is reduced, and bad cholesterol is decreased as a result of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin's therapeutic actions. In this meta-analysis research, intravascular ultrasound imaging showed that both medications may regress the composition of atherosclerotic plaques, raise the coronary artery lumen volume, and dramatically reduce atheroma volume. The rupture that results in vascular occlusion is avoided by the regression and stability of plaque. Blocking IL-8 or its receptors (CXCR1 and CXCR2) may reduce vascular inflammation, immune cell recruitment, and plaque progression. CXCR2 inhibitors are being explored for other inflammatory diseases and may have potential for CHD | [42,71] |

| IL-9 | IL-9 may contribute to the development of CAD and offer an innovative approach to its prevention and management. Blocking IL-9 or its IL-9R may help mitigate vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis progression | [48] |

| IL-10 | Therapeutic approaches that enhance IL-10 activity or mimic its effects hold promise for preventing and treating CHD. IL-10 levels might serve as a biomarker for anti-inflammatory activity and cardiovascular risk stratification | [51-57] |

As the body's initial line of defense against harmful microorganisms, the innate immune system depends heavily on the IL-1 cytokine family. As a quick reaction mechanism, the innate immune system defends against invasive pathogens before the adaptive immune response is completely triggered. Both IL-1α and IL-1β are pro-inflammatory chemicals that are generated in response to infection, tissue injury, and other inflammatory stimuli including stress, exposure to toxins, or allergens. To produce other inflammatory mediators and attract immune cells to the infection or damage site, these cytokines first bind to the IL-1R, which activates a signaling pathway. IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) is a competitive inhibitor of IL-1α and IL-1β, which stops them from binding to the IL-1R and reduces inflammation[11,12].

Atherosclerosis and heart failure may be pathophysiologically influenced by inflammatory cytokines. In the past, it was shown that chronic administration of IL-1β to the myocardial and coronary arteries causes cardiac dysfunction and coronary arteriosclerosis, respectively. In addition to directly promoting the atherosclerotic process, the cytokines in pericardial fluid may also indicate the degree of coronary atherosclerosis. Another study investigated the importance of the levels of cytokines in the pericardial fluid of patients with CVD. Pericardial IL-1β concentrations were considerably greater in the IHD group than in the CHD group or the valvular heart disease group. The pericardial levels of other cytokines did not significantly differ among the three groups. IL-1β concentrations were much higher in the IHD group in patients with unstable angina or those who had emergency surgery. According to these findings, pericardial IL-1β concentrations could indicate the degree of IHD, and high levels of IL-1β in pericardial fluid might also directly encourage the development of coronary atherosclerosis[13].

By activating the IL-1 receptor and triggering the activation of downstream inflammatory mediators, the archetypal proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 plays a crucial role in the innate immune response. Yang et al[14] examined the mechanisms behind the cardiovascular effects of IL-1RA. IL-1RA level assessed by genetics was linked to a higher incidence of MI and CHD. Furthermore, the levels of circulating apolipoproteins, fasting hyperglycemia, and different lipoprotein lipids were linked to IL-1RA. Curiously, the pattern of relationship with CHD that was identified was marginally diminished when other cardiometabolic risk variables were taken into account and reversed when apolipoprotein B was taken into account[14]. It was discovered that an appropriate lifestyle change reduced IL-1RA levels and lessened the increased risk of CHD it presented. The primary mediator and putative target for reversing the causative relationship between elevated blood IL-1RA and heightened risk of MI/CHD is apolipoprotein B. It is still unclear and debatable how IL-1RA contributes to the occurrence and progression of CHD. It would be worthwhile to investigate the combination therapy of lipid-modifying medication and IL-1 inhibition targeting apolipoprotein B further[14].

Another study measured the levels of IL-1β in the serum of patients suffering from IHD, to identify patient subgroups with elevated IL-1β levels, and to investigate potential correlations between serum IL-1β levels and non-specific measures of inflammation. Blood leucocyte counts, blood lymphocyte counts, and blood monocyte counts were not correlated with serum IL-1β concentrations nor were fibrinogen or C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations. Individuals with mild CAD and angina who have IHD had higher serum IL-1β concentrations[15].

Numerous effects on the various cell types found in coronary arteries are caused by IL-1β. Galea et al[16] located and characterized the IL-1β-producing cells in human coronary artery specimens from patients with cardiomyopathy or coronary atherosclerosis, and also established a relationship between the presence of IL-1β and the severity of the underlying illness. Using immunohistochemistry, luminal endothelium cells, adventitial vascular wall cells, and macro

The presence of IL-1β mRNA in the coronary artery wall was found using in situ hybridization. It was shown that the adventitial vessel walls of atherosclerotic coronary arteries had higher levels of IL-1β protein than coronary arteries from nonischemic cardiomyopathic hearts. This increase correlated directly with the degree of coronary atherosclerosis. Furthermore, in atherosclerotic coronary arteries and coronary arteries from nonischemic cardiomyopathic hearts, IL-1β protein was found in the luminal endothelium and macrophages. IL-1β mRNA was detected in macrophages, adventitial vascular EC, and luminal ECs. It may be concluded that in coronary arteries from ischemic hearts, ECs and macrophages create IL-1β, with nonischemic cardiomyopathic hearts producing less of it[16].

Mostly found in the endothelium of atherosclerotic plaques, the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 may be connected to inflammatory processes of atherogenesis. In part, the IL-1RA, a naturally occurring inhibitor of IL-1, regulates the complicated function of IL-1. Therefore, it investigated the specific and differential expression of IL-1RA isoforms in ECs activated under particular circumstances as well as in the endothelium of coronary arteries. The impact of ECs genotype at IL-1RN on IL-1RA protein production was also investigated due to a linked polymorphism in the IL-1RA gene (IL-1RN). Human atherosclerotic and dilated cardiomyopathic coronary arteries were examined using semiquantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction to detect secreted IL-1RA and intracellular IL-1RA mRNA. Protein expression seemed to be higher in atherosclerotic arteries than in dilated cardiomyopathic arteries, where IL-1RA seemed to be restricted to the endothelium. In human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) and human coronary artery ECs (HCAECs), only intracellular IL-1RA type I mRNA was found when the cells were treated with transforming growth factor beta (TGF-b) and bacterial lipopolysaccharide/phorbol myristate acetate. This is the first evidence of IL-1RA in human diseased arteries, stimulated HUVECs, and HCAECs, and it points to the ECs as an important source. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detection of IL-1RA in HUVEC lysates was influenced by the genotype of the IL-1RN variable number tandem repeat, an 86-bp repeat polymorphism in intron 2 of the IL-1RA gene, with lower levels of IL-1RA produced by IL-1RN allele 2-containing cells. These data further support the role of the IL-1 system of cytokines in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis[17].

Atherogenesis is influenced by inflammation. The prototypical inflammatory cytokine is IL-1. Another study explained that CAD is caused by an imbalance between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators in the IL-1 family and that 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) inhibitors (statins) may alter these mediators. IL-1β was one of 25 genes whose expression was downregulated by statins and elevated in CAD, according to a microarray screening experiment that looked at peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 6 patients with CAD and 5 healthy controls. These were a few main conclusions. (1) After 6 months of simvastatin (20 mg/d, n = 15) and atorvastatin (80 mg/d, n = 15) therapy, mRNA levels of IL-1β and IL-1β were significantly decreased in PBMCs from patients with CAD, but the reduction in IL-1RA was less pronounced; (2) mRNA levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-1RA were elevated in PBMCs from patients with stable and unstable angina compared with healthy control subjects; despite the unstable patients having particularly high levels of IL-1β and IL-1α, atorvastatin did not correspondingly increase PBMCs; and (3) IL-1β induced the release of proatherogenic cytokines from PBMCs, while atorvastatin partially eliminated this effect. The IL-1 family of cytokines may be therapeutic targets in CAD. The capacity of statins to modify these cytokines in an anti-inflammatory manner highlights their immunomodulatory potential[18].

To ascertain how IL-1 affects the vascular response to experimental damage in porcine models used for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). As long as it is administered for the whole time that the IL-1 system is being stimulated, which in this case is at least 28 days, the IL-1RA has been linked to a long-lasting, significant decrease in neointima following vessel wall damage. Accordingly, treatments that target the antagonism of IL-1 could alter how the coronary arteries react to damage[19].

IL-1 plays a central role in the pathogenesis of CHD by mediating inflammation and contributing to the development and progression of atherosclerosis. IL-1, particularly IL-1β, is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine that drives vascular inflammation. It is produced by activated monocytes, macrophages, and other immune cells in response to stimuli such as oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and necrotic cell debris. Targeting the IL-1 pathway has shown promise in reducing inflammation and cardiovascular events. Identifying patients with high inflammatory profiles (e.g., elevated IL-1β or high-sensitivity CRP [hsCRP] levels) could help tailor anti-inflammatory interventions. Investigating the roles of IL-1α and IL-1RA in CHD could further refine therapeutic strategies.

IL-2 is another cytokine signaling molecule. This protein, which is 15.5–16 kDa in size, controls the immune system-producing leukocytes or white blood cells, which are typically lymphocytes. The body uses IL-2 to distinguish between "self" and "non-self" stimuli and as part of its natural defense against microbial infection. By attaching to IL-2 receptors, which are produced by lymphocytes, IL-2 mediates its effects[20].

The fundamental cause of atherosclerosis, which is the basis for IHD and ACSs, is inflammation and dysregulated immune responses. Major factors influencing the post-ischemic damage following MI also include immune responses. Immune tolerance is induced and immunological homeostasis is maintained by regulatory T cells (Tregs). Low-dose IL-2 may be able to boost the number of Tregs, according to recent in vivo research. Human recombinant IL-2, known as aldesleukin, has been utilized therapeutically to treat several autoimmune disorders[21].

In the context of CAD, its safety and effectiveness are uncertain. A single-center, first-in-class, dose-escalation, two-part clinical study with low-dose IL-2 is being conducted in patients with stable IHD and ACS in which IL-2 (aldesleukin; dosage range 0.3–3 × 106 IU) or placebo is administered subcutaneously once daily for 5 days in patients with stable IHD (part A) and ACS (part B). Five patients in each group, representing five dosage levels, will be included in Part A. A dose of 0.3 × 106 IU was administered to Group 1, and the doses for the other four groups were decided once the previous group had finished. After the preceding group was finished, the doses for each of the next three groups were decided similarly. Finding the dosage that raises mean circulating Treg levels by at least 75% was the main goal, along with ensuring aldesleukin safety and acceptability[21].

Atherosclerosis is a long-term inflammatory condition affecting the arterial wall. Tregs reduce inflammation and aid in tissue repair. It is not recommended that patients with IHD utilize low doses of IL-2, although it may enhance Tregs. The involvement of unique pathways and cell-to-cell interactions was shown by single-cell RNA sequencing. Low-dose IL-2 increased Tregs in this Phase 1b/2a trial without causing any serious side effects. For individuals with IHD, larger studies are required to verify the safety and assess the effectiveness of low-dose IL-2 as an anti-inflammatory treatment[22].

IL-2 plays a complex and less direct role in the pathogenesis of CHD compared to other ILs like IL-1 or IL-6. Its primary functions are related to immune system regulation, and its involvement in CHD is primarily through its effects on immune activation, inflammation, and Tregs. Low-dose IL-2 selectively expands Tregs while minimizing effector T-cell activation, which has shown potential in reducing inflammation and autoimmune activity in experimental models. In CHD, low-dose IL-2 can theoretically help restore immune balance and reduce atherosclerosis-related inflammation. Identifying biomarkers for IL-2 pathway activity and immune dysregulation in CHD could improve patient stratification and therapeutic efficacy.

In conjunction with IL-1, IL-6, stem cell factor, and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, the cytokine IL-3 has been shown to promote the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells of distinct lineages. It has also been demonstrated that IL-3 may influence the activity of mature cells by sending out signals that are both mitogenic and mitogenic. Activated T cells produce IL-3, which is thought to be a mediator of chronic inflammation and an inducer of atherosclerosis. Activated T-lymphocytes emit cytokines, which have been demonstrated to be significant modulators of inflammatory and allergy responses. The formation of atherosclerotic lesions is thought to be influenced by cytokines, as chronic inflammation is a key factor in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis[23].

When comparing the levels of IL-3 in several subgroups of patients with CAD to those in healthy control patients, there is a lack of information on IL-3 in patients with CAD. IL-3 was found more often in patients receiving coronary angioplasty, compared to patients with asymptomatic CAD or without CAD. Detectable IL-3 levels were more common in patients with coronary angioplasty who experienced symptomatic restenosis than in individuals who did not[23].

In a multivariate study, IL-3 was the sole independent predictor of restenosis. hs-CRP did not correlate with IL-3 concentrations at any point; however, it was considerably higher in patients with ACS. Patients with CAD, especially those who are symptomatic and receiving PCI, have higher levels of IL-3, a key regulator of chronic inflammation. Moreover, a correlation between symptomatic restenosis and elevated IL-3 concentrations was discovered[23]. IL-3 may be involved in the process of vascular remodeling, making individuals with elevated levels of IL-3 especially vulnerable to coronary restenosis, as evidenced by research showing an increased risk for restenosis in patients with detectable IL-3 levels[23].

IL-3 is a cytokine involved in the regulation of hematopoiesis and the immune response. IL-3 promotes the activation and proliferation of various immune cells, including macrophages, mast cells, and T cells, which are key players in atherosclerosis. Blocking IL-3 activity could reduce vascular inflammation and plaque progression. Therapies aimed at reducing IL-3-induced immune activation could improve vascular outcomes. IL-3 levels might serve as a biomarker for CHD risk and severity. The efficacy of IL-3-targeted therapies should be assessed in the preclinical and clinical settings. By better understanding the role of IL-3 in CHD, researchers may uncover new strategies to mitigate inflammation-driven cardiovascular risk.

Among its numerous biological functions, IL 4 promotes the growth of activated B cells and T cells as well as the conversion of B cells into plasma cells. In humoral and adaptive immunity, it is a crucial regulator. The relationship between serum cytokine levels and the prevalence of CAD, a major cause of death worldwide that is strongly linked to inflammatory variables was investigated. According to the findings, serum levels of IL-4 and IL-17 are reliable indicators of CAD. The risk prediction model, which combines these serum cytokines (IL-4 and IL-17) with clinical risk factors (sex, smoking, and diabetes) and the protective factor HDL-C, might be able to distinguish between patients with CAD and those who may have CAD but do not have MI[9]. IL-4 levels in blood or atherosclerotic tissues could serve as biomarkers for assessing plaque stability and cardiovascular risk. The precise molecular mechanisms by which IL-4 influences CHD development need further investigation.

The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL 5 is mostly released by inflammatory cells, such as T lymphocytes, mast cells, macrophages, and eosinophils. IL-5 plays a significant role in the development, maturation, and discharge of eosinophils from bone marrow (BM). When IL-5 binds to the IL-5 receptor, it promotes the development of B cells and the release of more immunoglobulins, mostly immunoglobulin A[24].

Another study explored the potential causes and role of IL-5 in CAD. In the coronary plaque of patients with CAD, IL-5 was substantially lower than in the group of deceased donors. The coronary artery plaque's macrophages were the primary source of IL-5. Stable angina pectoris, unstable angina pectoris (UAP), and acute MI were the sequences from high to low plasma IL-5 levels in the CAD groups, which were considerably lower than those in the non-CAD group. The results of binary linear regression analysis indicated an independent correlation between IL-5 and the incidence of CAD. Type 1 T helper (Th1) and Th17 levels and the mRNA expression of their distinctive cytokines were reduced in CD4+Th cells treated with oxidized LDL after being treated with recombinant mouse IL-5[25].

A systemic febrile vasculitis with specific coronary artery involvement is seen in Kawasaki disease. There was a negative correlation between the incidence of coronary artery lesions and IL-5 levels[26]. The atheroprotective effects of IL-5 in atherosclerosis have been demonstrated to include promoting B-1 cell differentiation to release more T15/EO6 antibodies, which can inhibit macrophage absorption of oxidized LDL and decrease the production of foam cells[27]. Patients with ACS had lower plasma IL-5 levels than those with stable angina pectoris, according to this study. This suggests a connection between IL-5 and the stability of coronary lesion plaques[25].

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the region of the IL-5 gene were found to be linked with clinical illness in a gene-centric investigation of CAD, but to the best of our knowledge, replication of this locus has not been reported. Furthermore, the authors did not know how the IL-5 SNPs in that study were related to the plasma concentration of IL-5. They could not dismiss the possibility that the relationship of that locus with CAD is attributable to the effect(s) of other gene(s) in the region of IL-5[28].

Near the IL-5 locus, genetic polymorphisms were shown to be strongly linked to CAD and animal research indicated that IL-5 may have a preventive function against atherosclerosis. Thus, the purpose of another study was to investigate IL-5 as a plasma biomarker for early subclinical atherosclerosis, as assessed by carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) changes over time and baseline severity measurements. IL-5 levels were greater in the South than in the North of Europe, lower in women than in males, and positively correlated with the majority of known risk factors. IL-5 did not significantly correlate with baseline cIMT in either men or women, but it did exhibit significant inverse correlations with cIMT change over time in the common carotid segment in women. Based on findings, IL-5 may play a role in the preventive mechanisms that prevent early atherosclerosis, at least in women. Nevertheless, these connections are weak, and while IL-5 has been suggested as a possible molecular target for the treatment of allergies, it is hard to imagine a situation like that in CAD[29].

IL-5 plays a multifaceted role in CHD pathogenesis, with both pro-atherogenic and anti-atherogenic effects. Under

IL-6 is released by osteoblasts to promote the production of osteoclasts. In the tunica media of many blood arteries, smooth muscle cells also generate the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6. The anti-inflammatory myokine function of IL-6 is mediated by its stimulation of IL-1RA and IL-10 and its inhibition of TNF-α and IL-1. Produced at the site of inflammation, IL-6 is essential to the acute phase response, which is characterized by several biological and clinical characteristics, including the synthesis of acute phase proteins. The shift from acute to chronic inflammation is determined by IL-6 and its soluble receptor soluble IL-6Rα, which alters the type of leucocyte infiltration (from polymorphonuclear neutrophils to monocyte/macrophages). Furthermore, IL-6 stimulates T cells and B cells, which promotes long-term inflammatory reactions. Effective prevention and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis models and other chronic inflammatory illnesses were achieved using strategies that target IL-6 and IL-6 signaling. In chronic inflammation, IL-6 has a dual function, acting as a proinflammatory at certain levels and as a defense mechanism at others[30].

Potential roles for cytokines in the etiology and development of atherosclerosis exist. It reported the relationship between CAD angiographic severity and IL-6. Compared to controls, the patients' levels of IL-6 were higher and varied from 1.5 pg/mL to 3640.0 pg/mL. High Gensini score (GS) (> 40) levels were substantially correlated with high IL-6 levels, but not with a vascular score or stenosis degree. GS levels were much higher in patients with the high IL-6 group as compared to patients with low IL-6 levels[31].

IL-6 helps serve as a reliable biomarker for the degree of CAD as determined by GS and it is a key factor in the development of atherosclerosis. IL-6 may be a useful marker for assessing the degree of necrosis, and elevated levels may be associated with post-MI complications. This is based on the highest levels of IL-6 that were observed in individuals who had ST-segment elevation MI[31].

Since they reduce cholesterol and may have an anti-inflammatory impact, statins are being used extensively in the prevention of CAD. It is unclear, therefore, if their possible anti-inflammatory benefits are mediated by the IL-6 signaling system. Utilizing LDL levels as a stand-in, it demonstrated that HMG-CoA reductase had a substantial impact on upstream IL-6 and nominally significant impacts on Apolipoprotein B and IL-6RA. The multivariable MR model revealed that although the IL-6 signaling cascade and the anti-inflammatory effect of HMG-CoA reductase were found to influence the risk of CAD. The anti-CAD effect of statins may rely on inflammatory pathways other than the IL-6 signaling cascade. The definition of the target population for statin usage may change as a consequence of this finding[32].

Atherosclerosis is the primary cause of cardiovascular disorders, and the IL-6 pathway plays a critical role in its pathophysiology. In patients with ACS having PCI, another study evaluated the prognostic impact of inflammatory biomarkers on long-term cardiovascular mortality. It analysis revealed that IL-6 was a more accurate predictor of cardiovascular mortality than hsCRP. Elevated IL-6 values emerged as an independent and the most powerful predictor for cardiovascular mortality. In terms of mortality, IL-6 had a 9% positive predictive value, a 99% negative predictive value, a 94% sensitivity, and a 48% specificity. In individuals with high vs low IL-6 levels, the main endpoint of long-term cardiovascular mortality happened more frequently. High IL-6 levels are linked to a significant increase in long-term cardiovascular mortality in the context of ACS. In addition, IL-6 outperforms hsCRP as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality[33].

Several phases in the pathophysiology of CVD have been implicated in persistent inflammation. Inflammation cascades spread downstream by signaling from the IL-6R. It investigated a functional genetic mutation known to impact IL-6R signaling to determine if this route is causally related to CHD. Large-scale human genetic and biomarker data, which support a causal relationship between IL-6R-related pathways and CHD, have been made available by meta-analysis[34].

Asp358Ala is a frequent functional mutation in IL-6R. According to results, it is demonstrated that it is unrelated to a panel of traditional CVD risk factors, indicating that any influence of Asp358Ala on the risk of CHD is unlikely to be mediated by conventional risk factors. Second, it is observed that 358Ala carriage is linked, in a dose-dependent manner, to lower levels of fibrinogen and CRP, two distinct liver-derived proteins that accurately reflect the state of inflammation. These findings indicate that 358Ala attenuates the inflammatory response throughout the body. Third, in a similar dose-dependent fashion, findings demonstrate that 358Ala is substantially associated with a lower risk of CHD. Taken together, inflammation plays a role in CHD, and further research into IL-6R pathway modification is a potential pre

The inflammatory cascade in atherosclerosis is mostly influenced by IL-6, making it a chronic inflammatory disease. While IL-6 blockage may lower the risk of CVD, the present medications for IL-6 blockade also cause dyslipidemia, a condition for which there is no known cure. Using a 16-week prospective trial design, to ascertain the responses of endothelial function to anti-TNF-α, IL-6-blocking agent tocilizumab, and synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic medication therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Flow-mediated dilation percentage fluctuation before and after treatment was the primary result. The pre-treatment mean of flow-mediated dilation percentage variation in the tocilizumab group increases statistically significantly from 3.43% to 5.96%[35]. In the groups treated with synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and anti-TNF-α, the corresponding changes were 4.78% to 6.75% and 2.87% to 4.84% respectively (both not statistically significant). While total cholesterol did not increase significantly in the anti-TNF-α group, it did in the tocilizumab group from 197.5 to 232.3 and in the synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug group from 185.8 to 202.8. No group's HDL changed substantially. Tocilizumab raises total cholesterol and LDL levels, but in a high-risk group, it improves endothelial function[35].

IL-6 is not specific to CHD and can be elevated in various inflammatory conditions, infections, and autoimmune diseases, limiting its utility as a stand-alone diagnostic marker. IL-6 levels may fluctuate depending on acute and chronic inflammation, complicating its reliability as a consistent biomarker. There is no universally accepted cutoff for IL-6 levels in predicting CHD, making it challenging to integrate into clinical practice. IL-6 adds predictive information, but when used alongside established markers like high-sensitivity CRP and lipid profiles, its incremental value may be modest. While IL-6 has potential as a biomarker for cardiovascular risk stratification, its role is better suited as part of a multimarker approach rather than as a solitary measure. Further research is required to establish standardized guidelines for its use in clinical practice and to better delineate its utility in different patient populations, such as those with metabolic syndrome (MetS) or chronic inflammatory diseases.

The soluble globular protein IL-7 was later demonstrated to be 25 kDa in size. Fetal liver cells, BM stromal cells, thymus cells, and other epithelial cells, such as keratinocytes and enterocytes, are among the cells that generate IL-7. The IL-7 gene in humans encodes the protein known as IL-7[36]. T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and natural killer (NK) cells are among the immune cells whose growth and homeostasis are regulated by IL-7, which aids in host defense. Recombinant IL-7 has been shown safe and effective in immunological reconstitution in clinical studies. It is essential for maintaining health and preventing illness, and a congenital lack of IL-7 signaling results in severe immunodeficiency[37].

There have been reports linking the development of CHD to IL-7/IL-7R. Uncertainty persists about the connection between CHD in the Han Chinese population and IL-7/7R genetic variants. Carriers of the IL-7R rs969129 G allele and GG genotype were more likely to have CHD. The IL-7R haplotype "ACAG" was associated with a higher risk of CHD. The CHD susceptibility in men and/or the subgroup of people over 61 years of age was linked to rs969129, rs6451231, and rs117173992. Variants of IL-7R rs969129, rs10053847, rs6451231, and rs118137916 have been linked to diabetes in patients with CHD. Additionally, rs118137916 and rs10053847 were linked to LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, whereas rs969129, rs6451231, and rs117173992 were connected with HDL-C concentrations. Variants of IL-7/7R were linked to the Han Chinese population's genetic susceptibility to CHD[38].

The immune system has a role in atherogenesis and plaque destabilization, although the precise immunological mediators are still unknown. In addition to controlling T-cell homeostasis, IL-7 may potentially have a role in inflammation. Inflammatory mechanisms linked to ACS and atherosclerosis may include IL-7. It examined the levels of IL-7 and its impact on inflammatory mediators in patients with stable and unstable angina as well as in healthy control participants to investigate the function of this cytokine in CAD. Compared to healthy control participants, plasma levels of IL-7 were considerably higher in patients with stable and unstable angina, especially in those with unstable illness. One important factor contributing to the elevated IL-7 levels in patients with angina seems to be increased release from activated platelets. PBMCs from angina patients and healthy control participants, especially those with unstable illness, expressed more inflammatory chemokines when exposed to IL-7. T cells did not exhibit the same effects as monocytes. In a dose-dependent way, Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1α further enhanced platelets' release of IL-7. Aspirin was given to healthy control volunteers for seven days at a dose of 160 mg per day, and it decreased the levels of IL-7 in their plasma. It also decreased the release of IL-7 from platelets both spontaneously and in response to SFLLRN stimulation. Based on interactions between platelets, monocytes, and chemokines, the data point to a role for IL-7-driven inflammation in atherogenesis and the enhancement of clinical instability in CAD[39].

CAD is more common in those with diabetic foot problems. The factors that induce clinical instability towards CAD include hs-CRP, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and IL-7. Inducing inflammatory processes by upregulating MCP-1 expression and IL-7. An increased risk of CAD is indicated by abnormalities in the lipid profile of individuals with diabetic foot[40].

Blocking IL-7 or its receptor (IL-7R) may reduce T cell-mediated inflammation and slow atherosclerosis progression. IL-7R inhibitors are under investigation for autoimmune diseases and could be repurposed for CHD. IL-7 contributes to the pathogenesis of CHD by driving vascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and immune cell activation. Its role in linking metabolic inflammation and atherosclerosis highlights its potential as both a therapeutic target and a biomarker for cardiovascular risk management.

Chemokine IL-8 (also known as chemokine [C-X-C motif] ligand 8, or CXCL8) is generated by macrophages as well as other cell types such as ECs, epithelial cells, and airway smooth muscle cells. IL-8 is stored by ECs in Weibel–Palade bodies, which are storage vesicles. In humans, the CXCL8 gene encodes the IL-8 protein. First generated as a 99-amino acid precursor peptide, IL-8 is cleaved to yield many active IL-8 isoforms[41].

IL-8 is a crucial chemokine in atherogenesis and the development of CHD has a variety of roles that are still unknown. Another study evaluated the relationship between IL-8 expression and hyperlipidemia (H) in patients with CHD who are receiving statin cholesterol-lowering medication and coronary artery bypass grafting. After the condition was discovered, all of the patients with CHD had been on statin cholesterol-lowering drugs constantly. About a month later, they were having coronary bypass grafting[42].

As a result, the CHD group served as a good example of a pathogenesis improvement in CHD. In contrast to the N group, there was a substantial drop in the CHD group's IL-8 mRNA expression, whereas the H group's mRNA expression tended to rise. The CHD group exhibited a statistically significant decrease in both plasma levels and IL-8 mRNA expression when compared to the H group. The expression of IL-8 mRNA or plasma IL-8 showed a strong negative connection with the development of CHD. In summary, the patients with CHD who had been taking statins continuously showed a substantial reduction in both transcriptomic and phenotypic IL-8 expression when compared to the H and N group individuals. Consequently, IL-8 needs to function as a practical marker and be employed to assess the therapeutic benefits of statins as well as to depict the pathophysiology of CHD therapy[42].

One of the most prevalent types of cardiac disease is ACS. The formation of atherosclerotic plaques has been linked to IL-8, as demonstrated by recent investigations; however, the connection between ACS and common genetic variations of IL-8 has not been thoroughly investigated. The A/T polymorphism of IL-8−251 was linked to a higher risk of ACS. Patients with acute MI had higher levels of IL-8 in their plasma, indicating that IL-8−251 A/T could have an impact on IL-8 expression. In the Chinese Han population, the IL-8−251 A/T polymorphism is linked to an increased risk of ACS, and the IL-8−251 A/T A allele may operate as a stand-alone predictor of ACS[43].

To investigate how IL-8 may be used to predict the development of CAD in otherwise healthy individuals. The baseline IL-8 concentration was greater in cases compared to matched controls. There was an unadjusted hazard ratio of 1.72 for future CAD among those in the highest IL-8 quartile. The odds ratio for future CAD remained significant even after accounting for new parameters such as white cell count and CRP and after adjusting for conventional risk factors. It concluded that greater levels of IL-8 are linked to a higher risk of developing CAD in men and women. According to prospective findings, IL-8 plays a part in the progression of CAD occurrences[44].

The development of atherosclerosis and IHD has been linked to inflammation and the immune system. Serum levels of IL-8 and IL-12 were determined in patients suffering from acute MI (AMI) and UAP, and the results were compared to those of normal participants. As compared to healthy control participants, patients with AMI and UAP had considerably greater blood levels of IL-8. This is the first report of higher blood IL-12 levels in patents with AMI but not in patients with UAP. These results imply that IL-8 and IL-12 have a role in IHD and that IL-12 in serum might serve as a marker to distinguish between AMI and UAP[45].

Patients with ACS who had higher baseline plasma levels of IL-8 are also at a higher risk of long-term all-cause death. Additionally, current biomarkers with proven predictive value in ACS were not associated with this connection, despite several clinical, laboratory, and angiographic factors[46]. Blocking IL-8 or its receptors (C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 1 [CXCR1] and CXCR2) may reduce vascular inflammation, immune cell recruitment, and plaque progression. CXCR2 inhibitors are being explored for other inflammatory diseases and may have potential for CHD. Its central role in recruiting and activating immune cells makes it a promising therapeutic target and a potential biomarker for CHD management.

IL-9 is a pleiotropic cytokine (cell signaling molecule) that is a member of the IL group. Numerous cells, including mast cells, NK T cells, Th2, Th17, Tregs, type 2 innate lymphoid cells, and Th9 cells, release varying levels of IL-9. Th9 cells are thought to be the main CD4+ T cells that generate IL-9 among them. By activating distinct signal transducer and activator (STAT) proteins, including STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5, the IL-9R links this cytokine to several biological processes[47].

To conduct case-control association studies in a total of 3704 people from the Chinese Han population, four tag SNPs containing IL-9 (rs31563, rs2069868, rs2069870, and rs31564) were chosen. The findings indicated that first, rs2069868 was linked to CAD in conjunction with hypertension; second, the IL-9 haplotype (CGAT) was linked to CAD; and third, the combination genotype of “rs31563_CC/rs31564_TT” would significantly lower the risk of CAD. Significant correlations were also found between rs2069870 and lower levels of LDL-C and decreased total cholesterol levels, as well as between rs31563 and higher levels of HDL-C. By interacting with CAD's conventional risk factors, IL-9 may contribute to the development of CAD and offer an innovative approach to its prevention and management[48]. IL-9 is traditionally associated with allergic inflammation and immune regulation, but emerging evidence suggests it may play a role in the pathogenesis of CHD through its effects on vascular inflammation, immune cell activation, and atherosclerosis. Blocking IL-9 or IL-9R may help mitigate vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis progression.

The most significant cytokine with anti-inflammatory qualities, aside from TGF-b and IL-35, is IL-10. T-cell subsets such as Tregs, Th1 cells, as well as monocytes and macrophages, are the immune cells that create it. Comprising IL-10R1 and IL-10R2, the transmembrane receptor complex via which IL-10 operates controls the activities of several immune cells. In monocytes/macrophages, IL-10 increases their absorption of antigens while decreasing the generation of inflammatory mediators and preventing antigen presentation. Furthermore, IL-10 is significantly involved in the biology of T and B cells[49].

The dual role of IL-10 as both a pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine stems from its context-dependent effects and the diverse cellular pathways it influences. The cytokine classification as pro- or anti-inflammatory may not apply to IL-10's pleiotropic activities. Numerous data indicate that IL-10 improves NK cell activity, which increases antigen availability by destroying pathogens. Moreover, IL-10 prevents antigen-presenting cells from maturing, which maintains their capacity to absorb antigens while also impeding their migration to draining lymph nodes[50].

A cytokine having pleiotropic effects is IL-10. There may be a connection between IL-10 and CHD based on limited biochemical and clinical data. To elucidate the connection between IL-10 and CHD event risk, further information is necessary. Those whose IL-10 concentrations were at or above the median level (1.04 pg/mL) had higher incident rates than those whose concentrations were below the median level. In those with IL-10 concentrations ≥ 1.04 pg/mL, the cumulative incidence of CHD events was considerably higher. There was a 34% increased risk of a CHD incident for every standard deviation rise in baseline IL-10 levels. CRP, IL-6, and other cardiovascular risk variables did not reduce this higher risk. Diabetes had the strongest correlation between IL-10 levels and CHD event risk. Elevated IL-10 concentration was linked in the estrogen replacement and atherosclerosis trial to a higher chance of cardiovascular events in the future in postmenopausal women with existing coronary atherosclerosis. More research is necessary to determine the connection between IL-10 and the development and course of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events[51].

Produced by macrophages and T cells, IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine with additional anti-inflammatory properties. Extensive and unstable atherosclerotic lesions are the result of low levels of IL-10, as evidenced by animal research and the demonstration of IL-10 expression within human atherosclerotic plaques. Based on current data, IL-10 may have a preventive effect against atherosclerosis. There may be new options for the treatment of IHD as a result of this altered understanding of coronary disease as a chronic inflammatory process[52].

To reassess the relationship between the concentration of plasma IL-10 upon admission to the hospital and the outcome; to look at the role of SNPs in the IL-10 gene in patients who do not have ST-elevation ACS. IL-10 levels in healthy controls were found to be between 0.8 and 1.0 pg/mL, but in patients, they were found to be between 1.1 and 1.9 pg/mL. With the largest risk seen in the fourth quartile, IL-10 indicated a crude risk increase of death/MI in the patients. The connection was reduced to a non-significant level when common risk factors like IL-6 and CRP were taken into account. Consistent with the variant's moderate link with coronary disease, the 1170 CC genotype modestly predicted elevated plasma concentrations of IL-10 in both patients and controls. In contrast, IL-10 indicates a proinflammatory state in patients with ACS. As a result, IL-10 is a biomarker as useful as other systemic inflammation markers for predicting the risk of future cardiovascular events[53].

In the etiology of CAD, cytokines may play a significant role. Moghadam et al[54] determined the concentrations of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the serum and plasma of patients with CAD patients. The serum/plasma levels of IL-10 did not significantly differ between patients with CAD patients and healthy controls. Therefore, the etiology of CAD may be complicated and multiple.

Heart disease risk is increased by a set of risk factors known as MetS. In individuals with MetS, nothing is known about how IL-10 affects the severity of CAD. IL-10 and other pro-inflammatory cytokine plasma levels were examined in individuals with MetS who had or did not have severe CAD. Higher levels of IL-10 in patients with MetS are linked to a decreased risk of developing severe CAD, indicating that IL-10's anti-inflammatory properties may provide some protection even when pro-inflammatory cytokine levels are elevated[55].

Another study examined whether increased blood levels of IL-10 are linked to better endothelial vasoreactivity in individuals with CAD, as the endothelium is a prominent target for inflammatory cytokines. The development of atherosclerosis is significantly influenced by chronic inflammation. In experimental animals, IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, has significant protective benefits against the formation of atherosclerotic lesions. Using venous occlusion plethysmography, vasoreactivity was measured in 65 male patients with confirmed CAD by assessing endothelium-dependent (acetylcholine [Ach] 10 to 50 μg/min) and endothelium-independent (SNP 2 to 8 μg/min) forearm blood flow (FBF) responses. While serum levels of IL-10 did not correlate with SNP responses, they did substantially correlate with ACh-induced FBF responses[56].

Crucially, there was no reduction of the ACh-stimulated FBF response in individuals with elevated CRP levels if their blood levels of IL-10 were elevated. Only serum levels of IL-10 and CRP were significant independent predictors of ACh-induced FBF responses on multivariate analysis, which included LDL-C, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, clinical status of the patients, and statin and/or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor treatment. Therefore, individuals with raised CRP serum levels also have enhanced systemic endothelial vasoreactivity when their IL-10 serum levels are elevated. This suggests that a key factor influencing endothelial function in patients with CAD is the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators[56]. IL-10 plays a protective role in the pathogenesis of CHD by suppressing inflammation, stabilizing plaques, and preserving endothelial function. Its anti-inflammatory effects counterbalance the pro-inflammatory environment in atherosclerosis, making it a critical factor in cardiovascular health. Therapeutic approaches that enhance IL-10 activity or mimic its effects hold promise for preventing and treating CHD. IL-10 levels might serve as a biomarker for anti-inflammatory activity and cardiovascular risk stratification.

The overall summary of therapeutic strategies in CHD explain in Table 2. The development of CHD and atherosclerosis is significantly influenced by inflammation. ILs, a subset of cytokines, play a critical role in the pathogenesis of CHD by mediating inflammation, which is a key factor in atherosclerosis and its complications. ILs such as IL-1β and IL-6 are released in response to endothelial injury caused by risk factors like hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, and hyperglycemia. These cytokines promote the expression of adhesion molecules on ECs, facilitating the recruitment of monocytes and T-cells to the arterial wall. Once monocytes migrate into the intima, they differentiate into macrophages, ingest oxidized LDL, and form foam cells.

IL-1β and IL-8 amplify this inflammatory cascade by recruiting more immune cells and sustaining the inflammatory environment. Chronic inflammation driven by ILs leads to the accumulation of foam cells, smooth muscle cell pro

During acute coronary events, pro-inflammatory ILs, including IL-1β and IL-6, surge in the circulation. These cytokines amplify the systemic inflammatory response, exacerbate endothelial dysfunction, and promote further thrombosis. IL-1β and IL-6 exacerbate myocardial injury by sustaining inflammation and oxidative stress in the coronary vessels. Inflammatory markers such as CRP, IL-6, and IL-1β are useful in CHD risk prediction and monitoring[57]. Statin therapy can lower the risk of CHD in individuals with increased CRP but without hyperlipidemia. To find more new serum indicators with greater specificity for coronary artery plaque inflammation, extensive research is now underway. Future cardiovascular incidents may be avoided by using certain inhibitors of vascular inflammation in addition to statins, which are drugs that reduce LDL cholesterol[58].

IHD is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among cardiovascular illnesses, which continue to pose a worldwide health concern. The prognosis of elderly individuals with IHD is greatly impacted by their increased vulnerability to repeated ischemia episodes, even with the best pharmacological treatment. The development of atherosclerosis is significantly influenced by inflammation, which is closely related to ageing. New anti-inflammatory treatments have demonstrated the potential to lower ischemia episodes in high-risk groups. The purpose of this study is to investigate how tailored anti-inflammatory therapies could enhance clinical results and the standard of living for elderly patients with IHD[59].

CAD is still a significant problem for medical professionals despite advancements in pharmacological and interventional therapy, underscoring the need for novel and efficient treatments, such as anti-inflammatory drugs, to enhance results. It suggested that IL-1 and associated cytokines could be therapeutic targets for both stable and unstable CAD. Statins' capacity to alter this system in an anti-inflammatory manner emphasizes their potential for immunomodulation[18].

Conventional risk factors are linked to atherosclerosis and its consequences through inflammatory pathways, which also induce atherogenesis. In the treatment of CVD, one inflammatory mediator has gained attention. According to the experimental and clinical data examined here, IL-1β has a role in this both locally and systemically. Both lesional leukocytes and intrinsic vascular wall cells are capable of producing this cytokine. Using a molecular assembly called the inflammasome, local stimuli in the plaque promote the production of active IL-1β[60]. Anti-inflammatory treatments for atherosclerosis can enter a new age when clinically relevant approaches that block IL-1 activity enhance cardiovascular outcomes. This translational approach shows how improvements in fundamental vascular biology might change treatment. The authors wanted to provide patients with cardiovascular disease with more accurate and individualized treatment allocation through the use of biomarker-directed anti-inflammatory strategies[60].

On the one hand, it has been suggested that blocking the IL-1 pathway may stop the development of certain CVDs, such as atherosclerosis, MI, and heart failure. This is because IL-1RA is known to bind to the IL-1 receptor, preventing the binding of both IL-1α and IL-1β[61,62].

A major pathogenetic mechanism in the development, progression, and complications of atherosclerosis as well as the myocardial response to ischemia and nonischemic damage is the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and the IL-1 family of cytokines. Clinical studies of patients with or at risk for AMI, HF, and recurrent pericarditis have previously demonstrated that IL-1-targeted treatments enhance cardiovascular outcomes. In a major Phase 3 clinical study including 10061 patients worldwide, canakinumab, an IL-1β antibody, protected ischemic episodes from recurring in individuals who had previously experienced AMI. HF, Anakinra, a recombinant IL-1RA, has shown encouraging results in Phase 2 clinical studies for patients with ST-segment-elevation AMI or HF with impaired EF. Additionally, Anakinra helped patients with pericarditis, and it is currently the standard of care for patients with recurrent or refractory pericarditis as a second-line therapy. Additionally, Phase 2 research in recurrent/refractory pericarditis has shown encouraging outcomes for rilonacept, a soluble IL-1 receptor chimeric fusion protein that neutralizes IL-1α and IL-1β. Another useful therapy for pericarditis is colchicine, a nonspecific NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor and inhibitor of IL-1-driven leukocyte migration. It has also been demonstrated lately to lower the incidence of recurrent ischemic episodes in patients with AMI. It is yet unknown if colchicine's effects on CVD have been mediated via NLRP3 inflammasome or IL-1 signaling. Clinical research is underway for some oral NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors. Thus, the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1 cytokines are strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of CVDs. In the future, a variety of CVDs will probably be treated with targeted inhibitors to block the IL-1 isoforms and perhaps oral NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors[5].

Another study did not find strong statistical support for the role of genetically predicted IL-5 inhibition in CVD risk. These data support the notion that IL-5i medication is unlikely to raise the risk of thromboembolic or cardiovascular disorders, but they require confirmation by pharmacovigilance studies with sufficient power[63].

It is no longer believed that atherothrombosis is only a condition caused by lipoprotein buildup in the artery wall. Instead, it is now known that aspects of the innate and acquired immune systems play a significant role in the deve

Currently, extensive Phase 3 studies are being conducted with drugs that significantly lower IL-6 and CRP (cana

An essential cytokine of innate immunity, IL-6 performs a wide range of physiological processes that are often linked to host defense, immune cell control, proliferation, and differentiation. Since the identification of innate immune path

The authors explained a summary of the processes behind IL-6 signaling and their effects on pharmacological inhibition. Elucidate atherogenesis and IL-6 in mouse models; provide an overview of the human epidemiological evidence supporting the usefulness of IL-6 as a biomarker of vascular risk; describe genetic evidence pointing to a causal role for IL-6 in the development of aneurysms and systemic atherothrombosis; and then describe the possible involvement of IL-6 inhibition in heart failure, ACS, stable coronary disease, and the atherothrombotic complications linked to chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal failure[65].

Also, it concluded by reviewing the anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic results for ziltivekimab, a novel IL-6 ligand inhibitor being developed specifically for atherosclerotic disease and about to undergo formal testing in a large-scale cardiovascular outcomes trial aimed at people with elevated CRP and chronic kidney disease, a population with a high residual inflammatory risk, a high residual atherothrombotic risk, and a significant unmet clinical need[65].

Human health is seriously threatened by coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. The ongoing discussion on anti-inflammatory therapy for coronary atherosclerotic heart disease was resolved in 2017 by the findings of the Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study. During the past 3 years, clinical trials have shown promising outcomes for colchicine, IL-6RAs, and IL-1β monoclonal antibodies. There are still issues that need to be resolved, nevertheless, notwithstanding these achievements. The authors examined the effectiveness and current uncertainties of colchicine, IL-6RAs, and IL-1β antibodies in the anti-inflammatory management of coronary atherosclerotic heart disease[66].

Another study demonstrated that patients with CHD taking 20 mg of rosuvastatin or 40 mg of atorvastatin reached the LDL-C goal (< 100 mg/dL), which was consistent with earlier 30-day treatment studies[67,68]. It was also demonstrated that atorvastatin attenuated neutrophil migration after 2 weeks of exposure to a high dose (80 mg) and decreased IL-8 expression in a dose-dependent manner[69]. Furthermore, statins inhibit leukocyte and ECs interactions and decrease the number of inflammatory cells within atherosclerotic plaques[70].

Coronary atherosclerotic plaques are reduced, vascular inflammation is reduced, and bad cholesterol is decreased as a result of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin's therapeutic actions. In this meta-analysis research, intravascular ultrasound imaging showed that both medications may regress the composition of atherosclerotic plaques, raise the coronary artery lumen volume, and dramatically reduce atheroma volume. The rupture that results in vascular occlusion is avoided by the regression and stability of plaque[71].

Previous studies have indicated that rosuvastatin inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase and NF-κB to reduce the inflammatory response. Additionally, adhesion molecules and some cytokines, including IL-8, IL-6, and MCP-1, have been discovered to be decreased by it[72]. In addition to lowering bad cholesterol and vascular inflammation, rosuvastatin and atorvastatin also cause coronary atherosclerotic plaques to recede[71].

Commonly used medicinal compounds or specific molecules with focused anti-inflammatory effects can target these molecules. Together with newer treatments like TNF-α inhibitors and IL-1RAs, the most important anti-inflammatory medications include aspirin, statins, colchicine, IL-1β inhibitors, and IL-6 inhibitors. Because of their pleiotropic and anti-inflammatory properties, aspirin and statins are well-established treatments for atherosclerosis and CAD. According to the latest guidelines, high-risk individuals may also be evaluated for colchicine if they experience recurring bouts of ACS while receiving adequate medical treatment[73].

Though they have not yet been widely used in clinical practice, recent randomized studies have also demonstrated that treatments that particularly target inflammation and inflammatory ILs can lower the risk for cardiovascular events. Targeting several inflammatory mediators thought to be connected to CAD, preclinical research is also thorough. These include NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors, chemokine modulatory treatments, IL-10 delivery via nanocarriers, reactive oxygen species targeting nanoparticles, and repeated transfers of the soluble mutant of IFN-γ receptors. Though interesting and promising, such methods should be used in clinical settings before any firm conclusions can be made. More research is required to clarify this relationship and enhance outcomes for patients with CAD, despite the substantial correlation between inflammation and atherosclerosis[73].

It is known that systemic inflammation is a significant factor in the development and advancement of CVD. Based on the foregoing analysis of the scientific and clinical evidence, it may be inferred that anti-inflammatory medication that targets certain pro-inflammatory mediators may, in some cases, offer protection against CVD and, as a result, offer an alternative therapeutic approach for managing CVD. The particular anti-inflammatory route addressed may be essential for achie

Since aspirin and statins have been shown to lower mortality in individuals with CAD or those at higher risk for future events, their anti-inflammatory qualities contribute to their positive cardiovascular profile and therapeutic use. Additionally, low-dose colchicine (0.5 mg once daily) may be taken into consideration for secondary prevention of CVD, especially if recurrent events occur under optimal therapy, as per the European Society of Cardiology's 2021 guidelines on CVD prevention[75].

The Canakinumab Antiinflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study trial recently demonstrated, for the first time, that IL-1β suppression, an isolated medication that targets inflammation, might lower the risk of cardiovascular events and may be helpful for patients recovering from ACS. However, the non-significant impact on all-cause mortality and the elevated risk for non-cardiac problems have made it necessary to create more unique therapeutic approaches and better choose individuals who are more likely to react to anti-inflammatory treatments. Other new treatments have also surfaced, and a big randomized study investigating the therapeutic potential of IL-6 inhibition is now under progress. The results of these investigations may support the use of medications that target inflammation specifically to lower cardiovascular risk in people with established CAD[73].

As clinically useful biomarkers, ILs have great potential for early and accurate illness identification, which will increase the effectiveness of treatment. This is particularly important for infectious diseases and other disorders where early diagnosis is still very difficult. Reflecting the condition of the immune system is one of the main roles of ILs as biomarkers[6].

According to the literature, many ILs are involved in the pathogenesis of CHD however, this article did not report the other ILs in the pathogenesis of CHD such as IL 11 to other ILs. It is still unclear and debatable how IL-1RA contributes to the occurrence and progression of CHD. The exact function of IL-1β in CAD is yet unknown. For individuals with IHD, larger studies are required to verify the safety and assess the effectiveness of low-dose IL-2 as an anti-inflammatory treatment. More research is necessary to determine the connection between IL-10 and the development and course of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. The exact signaling pathways involved in ILs in CHD remain poorly understood. The interplay between IL-driven inflammation and comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, chronic kidney disease) is not fully characterized. Limited research on how lifestyle interventions (e.g., diet, exercise, smoking cessation) modulate IL levels and influence CHD progression.

IILs are a group of cytokines that play critical roles in the immune system by regulating inflammation, immune responses, and hematopoiesis. In the context of CHD, ILs contribute to the pathogenesis through their involvement in the inflammatory processes that underlie atherosclerosis which is the primary cause of CHD. ILs are integral to the pathogenesis of CHD, primarily through their roles in promoting inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, plaque formation, and thrombosis. This article also concluded that ILs (IL-1 to IL-10) played a significant role in the pathogenesis of CHD as explained in the figure and tables. Further studies are required to find the role of other ILs in CHD. The exact signaling pathways involved in ILs in CHD remain poorly understood.

| 1. | Anderson L, Thompson DR, Oldridge N, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, Taylor RS. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016:CD001800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Falk E, Nakano M, Bentzon JF, Finn AV, Virmani R. Update on acute coronary syndromes: the pathologists' view. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:719-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 676] [Cited by in RCA: 737] [Article Influence: 56.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ranjit N, Diez-Roux AV, Shea S, Cushman M, Seeman T, Jackson SA, Ni H. Psychosocial factors and inflammation in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:174-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |