Published online Mar 5, 2025. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v16.i1.98515

Revised: October 14, 2024

Accepted: December 5, 2024

Published online: March 5, 2025

Processing time: 249 Days and 19.4 Hours

Skin wounds are common injuries that affect quality of life and incur high costs. A considerable portion of healthcare resources in Western countries is allocated to wound treatment, mainly using mechanical, biological, or artificial dressings. Biological and artificial dressings, such as hydrogels, are preferred for their biocompatibility. Platelet concentrates, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), stand out for accelerating tissue repair and minimizing risks of allergies and rejection. This study developed PRF and PRP-based dressings to treat skin wounds in an animal model, evaluating their functionality and efficiency in accelerating the tissue repair process.

To develop wound dressings based on platelet concentrates and evaluating their efficiency in treating skin wounds in Wistar rats

Wistar rats, both male and female, were subjected to the creation of a skin wound, distributed into groups (n = 64/group), and treated with Carbopol (negative control); PRP + Carbopol; PRF + Carbopol; or PRF + CaCl2 + Carbopol, on days zero (D0), D3, D7, D14, and D21. PRP and PRF were obtained only from male rats. On D3, D7, D14, and D21, the wounds were analyzed for area, contraction rate, and histopathology of the tissue repair process.

The PRF-based dressing was more effective in accelerating wound closure early in the tissue repair process (up to D7), while PRF + CaCl2 seemed to delay the process, as wound closure was not complete by D21. Regarding macroscopic parameters, animals treated with PRF + CaCl2 showed significantly more crusting (necrosis) early in the repair process (D3). In terms of histopathological parameters, the PRF group exhibited significant collagenization at the later stages of the repair process (D14 and D21). By D21, fibroblast proliferation and inflammatory infiltration were higher in the PRP group. Animals treated with PRF + CaCl2 experienced a more pronounced inflammatory response up to D7, which diminished from D14 onwards.

The PRF-based dressing was effective in accelerating the closure of cutaneous wounds in Wistar rats early in the process and in aiding tissue repair at the later stages.

Core Tip: This study compares the effects of dressings made from platelet concentrates platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), platelet-rich plasma, and PRF activated with CaCl2 - on accelerating the tissue repair process and closing cutaneous wounds in Wistar rats. The results indicated that the PRF dressing accelerated wound closure and tissue repair.

- Citation: Sá-Oliveira JA, Vieira Geraldo M, Marques M, Luiz RM, Krasinski Cestari F, Nascimento Lima I, De Souza TC, Zarpelon-Schutz AC, Teixeira KN. Bioactivity of dressings based on platelet-rich plasma and Platelet-rich fibrin for tissue regeneration in animal model. World J Biol Chem 2025; 16(1): 98515

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8454/full/v16/i1/98515.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v16.i1.98515

Skin wounds are prevalent discontinuity lesions in the global population, significantly impacting the quality of life of affected individuals and the economy, both due to the scientific investment in treatments and the high cost of clinical management[1]. Regarding wound treatment costs, it is estimated that about 1% of healthcare resources in Western countries are allocated for this purpose[2].

Dressings are the most common method for wound treatment, whether mechanical, biological, or artificial. In general, they offer significant benefits, such as protecting the wound from external agents, good biocompatibility, and easy application. However, because they require frequent changes, mechanical dressings can cause abrasion of the lesion, which may progress to ischemia and necrosis. Thus, biological dressings can be more advantageous due to their biocompatibility and biodegradability, while artificial dressings, such as hydrogels, are advantageous because of their porous structure, resulting in better fluid adsorption and oxygen exchange[3].

Despite advances in treatments, the resources for wound coverage that can accelerate the tissue repair process are still scarce, and the cost-benefit ratio must be considered to make them viable. In this context, platelet concentrates offer unique advantages for their use as a therapeutic method. Platelet concentrates, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), are used in various fields of medicine and dentistry to optimize the tissue repair process by concentrating and providing a prolonged release of growth factors and other autologous molecules[4,5].

Other advantages are that, being a by-product for autologous use, there is a considerable reduction in triggering allergic reactions or rejection and in the transmission of diseases via the parenteral route, besides being a resource that is quickly and easily obtained. Thus, this study aimed to develop PRP and PRF-based wound coverings for the treatment of excisional skin wounds in an animal model and to evaluate the functionality and efficiency of these dressings in accelerating the tissue repair process.

This study was approved by the Animal Use Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal do Paraná (Approval 1499/R.O. 11/2022). The experiments were conducted on Wistar strain rats (Rattus norvegicus). For the preparation of platelet concentrates PRP and PRF, healthy male rats over 90 days old and weighing over 500 g were used. For the skin wound experiments, male and female rats, aged 90 to 120 days and weighing 250 to 350 g, were used. The animals were kept under controlled conditions of temperature (22 ± 2.0 ºC), a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and received pelletized feed and water ad libitum. They underwent an adaptive handling period of 15 days before the start of the experiments.

The animals were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (90/9 mg/kg; i.p.), and 5 mL of whole blood was collected via cardiac puncture using a 10 mL syringe and a 22G1” needle. For obtaining PRF, the protocol described by Dohan et al[6] with modifications was used. The whole blood was subjected to a single centrifugation at 400 G for 10 minutes in 10 mL polypropylene tubes, ensuring that the interval between puncture and centrifugation did not exceed 60 seconds. For obtaining PRP, the protocol described by Borges[7] with modifications was used. The whole blood was centrifuged at 300 G for 10 minutes in a tube containing 3.2% (w/v) sodium citrate. The plasma was transferred to a Falcon tube and centrifuged at 640 G for 10 minutes. The upper 2/3 was considered platelet-poor plasma and discarded, and the final 1/3 was used as platelet concentrate-PRP. The PRP was collected and incubated with 1.7 mmol/L CaCl2 (calcium chloride) at 37 °C for 30 minutes.

To facilitate the application of platelet concentrates and allow for prolonged contact with the skin wound, they were incorporated into a Carbopol 940 hydrogel. Carbopol 940 is an acrylic polymer that forms a hydrogel with biological adhesion and prolonged residence time when applied topically to the skin[8]. Separately, the platelet concentrates were incorporated into a 0.75% (w/v) Carbopol 940 gel in sterile 0.9% (w/v) NaCl solution. Three types of dressings were prepared: (1) PRP + Carbopol 940; (2) PRF + Carbopol 940; and (3) Activated PRF + Carbopol 940. The latter was obtained by adding 1.7 mmol/L CaCl2 followed by incorporation into the Carbopol 940 gel and incubation at 37 °C for 30 minutes before use.

The animals were sedated with isoflurane 3%-4% for induction and 1.5%-2% for maintenance, in 100% oxygen. Subsequently, the dorsal region of the animal, 2 cm from the base of the neck, was shaved. Local antisepsis was performed with 10% (w/v) chlorhexidine digluconate, and local anesthesia was administered with 5 mg/kg lidocaine hydrochloride (s.c.). Using a 1.5 cm diameter metal punch and a scalpel, a circular wound was created. The skin was completely removed down to the muscular fascia, and the wound was cleaned with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl solution and gauze.

The animals were randomly divided into four experimental groups (n = 64/group): Carbopol 940 0.75% (w/v) (negative control), PRP + Carbopol 940 0.75% (w/v) (PRP), PRF + Carbopol 940 0.75% (w/v) (PRF), and PRF + CaCl2 + Carbopol 940 0.75% (w/v) (PRF + CaCl2). Each animal received a topical application of the respective treatment (300 μL) once a day on the day of wound creation (D0), 3 (D3), 7 (D7), 14 (D14), and 21 (D21) days after wound creation. All treatments were prepared on the day of each application, and the wounds were pre-cleaned and debrided with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl solution and gauze before the treatment application.

On days 3, 7, 14, and 21, 16 animals from each group were randomly euthanized by overdose of isoflurane, followed by visual and morphometric evaluation of the wounds. The wounds were photographed, and the lesion area was calculated using ImageJ® software (National Institutes of Health). The macroscopic analysis was performed using parameters adapted from the Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool, as described by Harris et al[9]. The evaluated parameters included wound appearance (regarding necrosis), type of exudate, wound bed (regarding granulation tissue), and epithelialization (regarding the covered area). All parameters were assessed using a tissue damage score (1 to 5). The wound contraction rate was calculated using the equation [% contraction = 100 (Wo-Wi)/Wo], where Wo = initial wound area and Wi = wound area on the observed experimental day, as described by Al-Watban and Andres[10] and Oliveira et al[11].

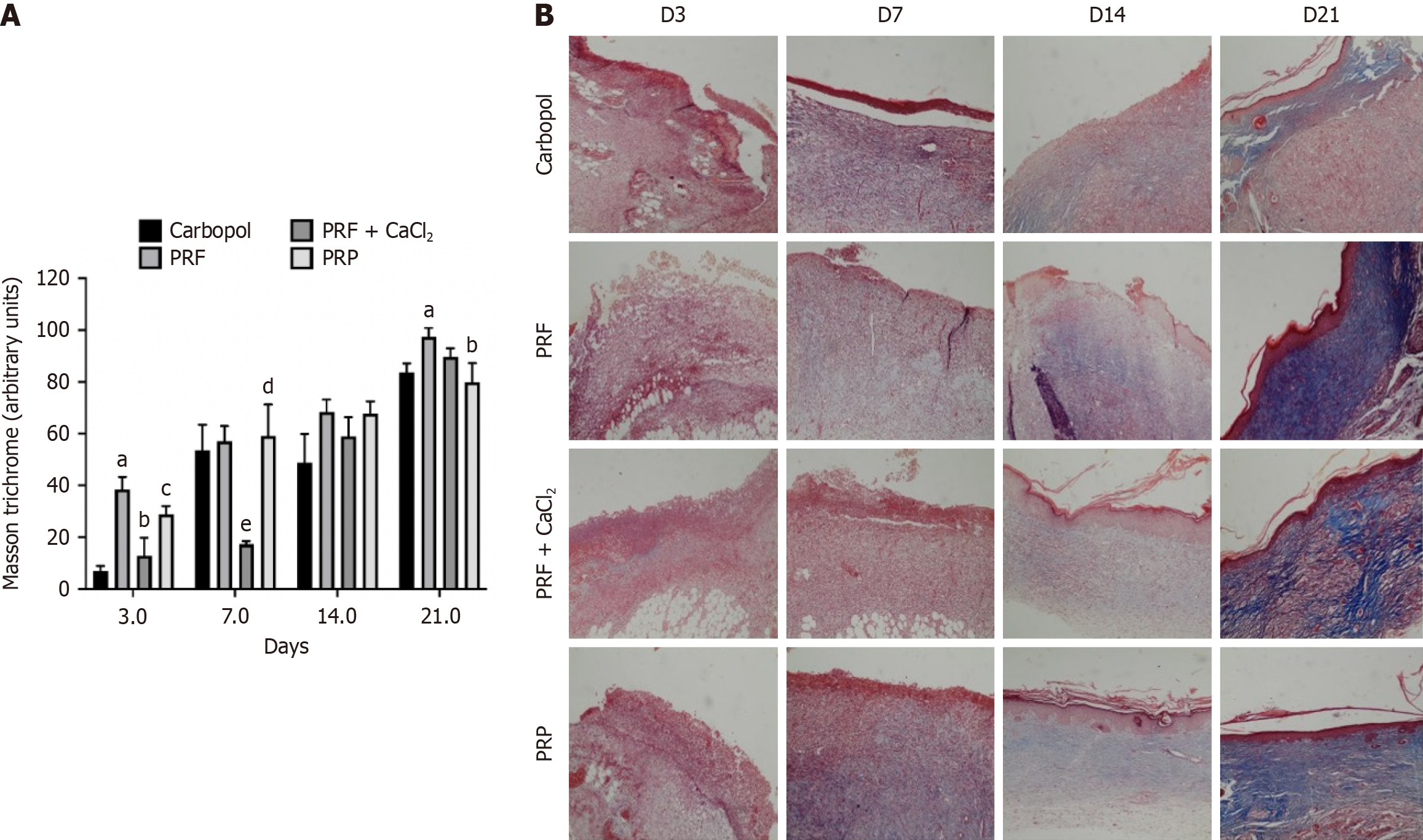

Histological analysis was performed by removing a biopsy of the injured skin area with 0.5 cm margins on D3, D7, D14, and D21. The samples were fixed in 3.7% buffered formalin (v/v) to prepare histological slides, which were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) according to Garro et al[12], and Masson's trichrome (MT) according to Coleman[13], with modifications, to evaluate the organization and maturation of collagen fibers. A blinded pathologist performed the histopathological analysis, assigning scores according to the protocols by Harris et al[9]. For the quantitative evaluation of collagenization intensity, digitized images of the TM-stained histological sections were analyzed using ImageJ 1.54 g software (National Institutes of Health). Three regions of each histological section, with the same area (cm²), were analyzed for all experimental groups on D3, D7, D14, and D21.

The mean values obtained for each group of animals in each experiment were calculated and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software. Tukey's test was used to compare the groups within each treatment. Results with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

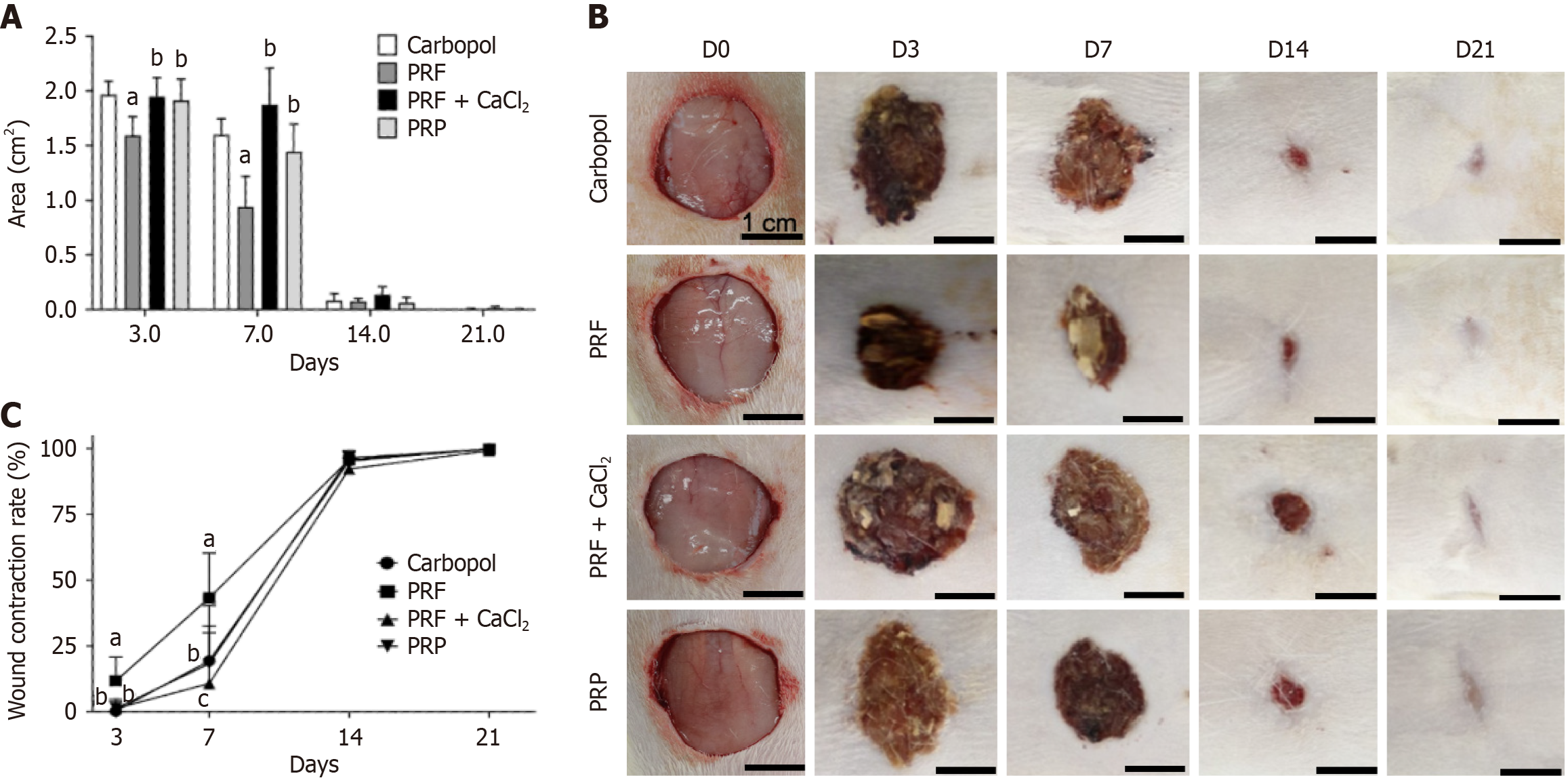

The analysis of the skin wound area in animals treated with Carbopol, PRF, PRF + CaCl2, and PRP was conducted on D3, D7, D14, and D21. On D3, a significant reduction in wound area was observed in animals treated with PRF compared to the other groups. On D7, animals treated with PRF continued to show a significant reduction in wound area compared to the other groups. However, the PRP-treated group showed a significant reduction in wound area compared to the PRF + CaCl2 group, indicating increased efficiency of PRP in accelerating tissue repair from D3 to D7. On D14 and D21, no significant differences were observed between the experimental groups. By D21, the control group animals and most of the animals in the PRF and PRP groups had no remaining wound area, while most animals treated with PRF + CaCl2 still had a wound area (Figure 1A). A visual representation of the wound areas during the experiment is shown in Figure 1B.

Regarding the contraction rate of the skin wounds in animals treated with PRF, there was a linear increase from D3 to D14. On D7, the contraction rate approached 50% in the PRF group, compared to less than 25% in the other groups. On D3 and D7, the contraction rate in the PRF-treated group was significantly higher than in the negative control, PRF + CaCl2, and PRP groups. Additionally, on D7, the PRP group showed a significantly higher contraction rate than the PRF + CaCl2 group. From D14 onwards, no significant differences were observed between the experimental groups, and all groups had a contraction rate greater than 90%. On D21, the negative control group had a contraction rate of 100%, followed by most animals in the PRF and PRP groups. Animals treated with PRF + CaCl2 had a contraction rate between 97.6% and 100%, corroborating the wound area reduction data for the same period (Figure 1C).

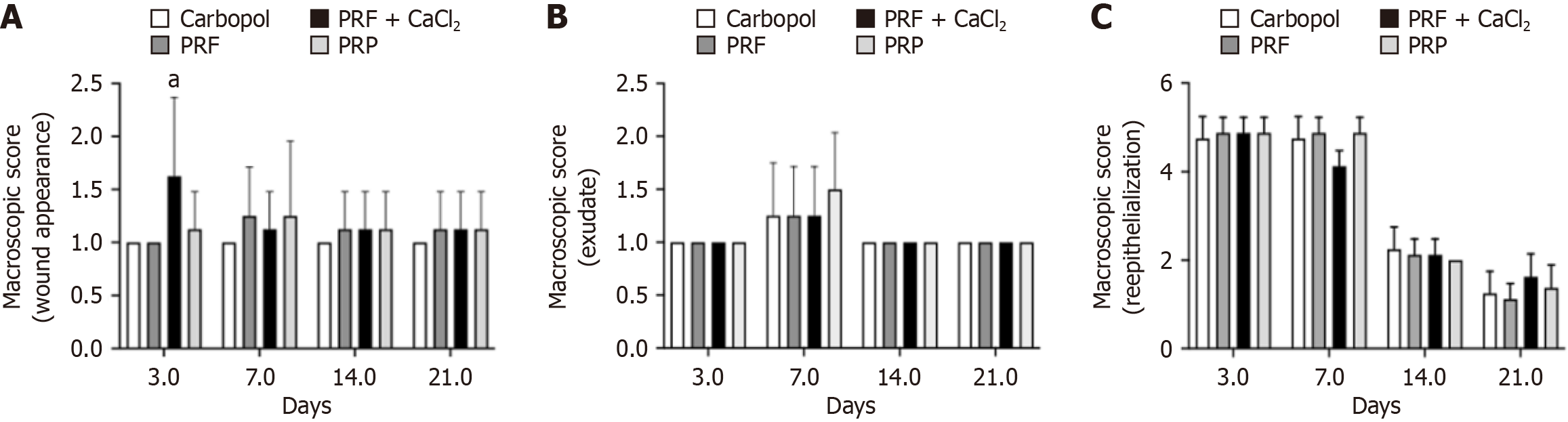

The analysis of macroscopic parameters of the skin wounds showed that regarding wound appearance, all experimental groups on D3, D7, D14, and D21 exhibited either a thick crust firmly adhered, covering 75% to 100% of the wound (score 1), or a soft and adhered crust covering 50% to 75% of the wound (score 2). A significant difference was observed only on D3, indicating that the PRF + CaCl2 group had a more pronounced parameter (Figure 2A). For the parameter "type of exudate", on D3, no exudate (score 1) was observed in any experimental group (100% of animals). On D7, it was observed that in all groups, some animals exhibited serosanguinous exudate (score 2). By D14 and D21, there was no exudate present in any of the experimental groups (100% of animals). There was no significant difference observed for this parameter (Figure 2B).

The reepithelialization score measures the area of the wound with new epithelial formation, and this score decreases with increased reepithelialization. Although no statistical difference was observed between the PRF, PRF + CaCl2, PRP, and Carbopol groups on any experimental day, the reepithelialization process progressed towards tissue repair. On D3 and D7, all groups showed high scores, indicating less than 25% (score 5) or 25 to 50% (score 4) of the wound area reepithelialized. By D7, all experimental groups (100% of animals) exhibited 75 to less than 100% of the wound area reepithelialized (score 2), and on D21, the groups presented animals with scores of 2 and 1 (100% of the wound reepithelialized), with a predominance of the latter except for the PRF + CaCl2 group, in which the majority of animals still did not have 100% of the wound reepithelialized (Figure 2C).

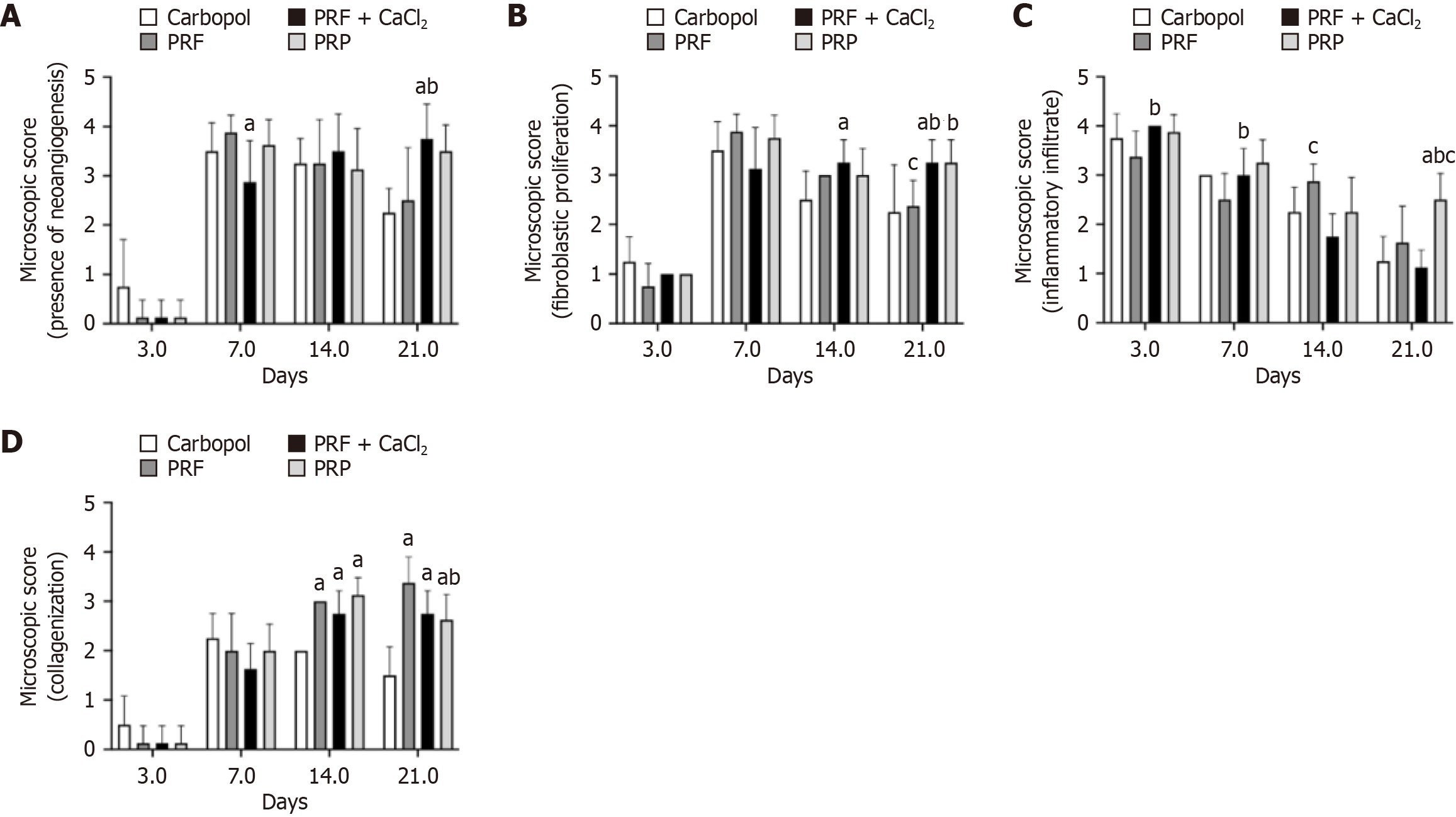

Microscopic analysis of the skin wounds indicated that on D3, all experimental groups showed less than 25% of the wound area with new blood vessel formation, with no statistical difference between the groups. From D 3 to D7, there was an increase in new vessel formation. By D7, the PRF + CaCl2 group exhibited significantly lower neoangiogenesis (scores 2 and 3 - new vessels in 25%-50% and 50%-75% of the wound area, respectively) compared to the Carbopol group (scores 3 and 4; 4 = new vessels in 100% of the wound area). By D21, the PRF + CaCl2 group showed significantly higher neoangiogenesis compared to both the Carbopol group (scores 2 and 3) and the PRF group (with a predominance of score 3), with most animals exhibiting 100% of the wound area with new vessels (score 4) (Figure 3A).

Regarding fibroblast proliferation, on D3, most animals across all experimental groups exhibited less than 25% of the wound area with fibroblasts, with no statistical differences between the groups. From D14, fibroblast proliferation increased and generally remained high until D21. On D14, fibroblast proliferation was significantly higher in the PRF + CaCl2 group, with 50%-75% or 100% of the wound area containing fibroblasts (scores 3 and 4, respectively), compared to the Carbopol group, in which animals had 25%-50% (score 2) or 50%-75% (score 3) of the wound area with fibroblasts. By D21, fibroblast proliferation in the PRF + CaCl2 group (scores 3 and 4) remained significantly higher than in the Carbopol group (scores 2 and 3) and the PRF group (scores 2 and 3), while the PRP group (scores 3 and 4) showed significantly higher fibroblast proliferation compared to the PRF group (Figure 3B).

The presence of inflammatory infiltrate in the wound area was significantly higher in the PRF + CaCl2 group compared to the PRF group on D3 and D7. On D3, animals in the PRF + CaCl2 group had inflammatory infiltrate in 100% of the wound area (score 4), while the PRF group had inflammatory infiltrate in 50%-75% (score 3) or 100% of the wound area. By D7, most animals in the PRF + CaCl2 group exhibited inflammatory infiltrate in 50%-75% of the wound area, whereas the PRF group had infiltrate in 25%-50% (score 2) or 50%-75% (score 3) of the wound area. On D14 and D21, the PRF + CaCl2 group had a smaller area with inflammatory infiltrate compared to the PRF group, with a significant difference on D14. On D14, the PRF + CaCl2 group had inflammatory infiltrate in 25%-50% of the wound area, whereas the PRF group had inflammatory infiltrate in 50%-75% of the wound area. Overall, the inflammatory infiltrate decreased over time (D3-D21), except for the PRP group, which on D21 showed a significantly larger area of inflammatory infiltrate compared to the Carbopol, PRF, and PRF + CaCl2 groups (Figure 3C).

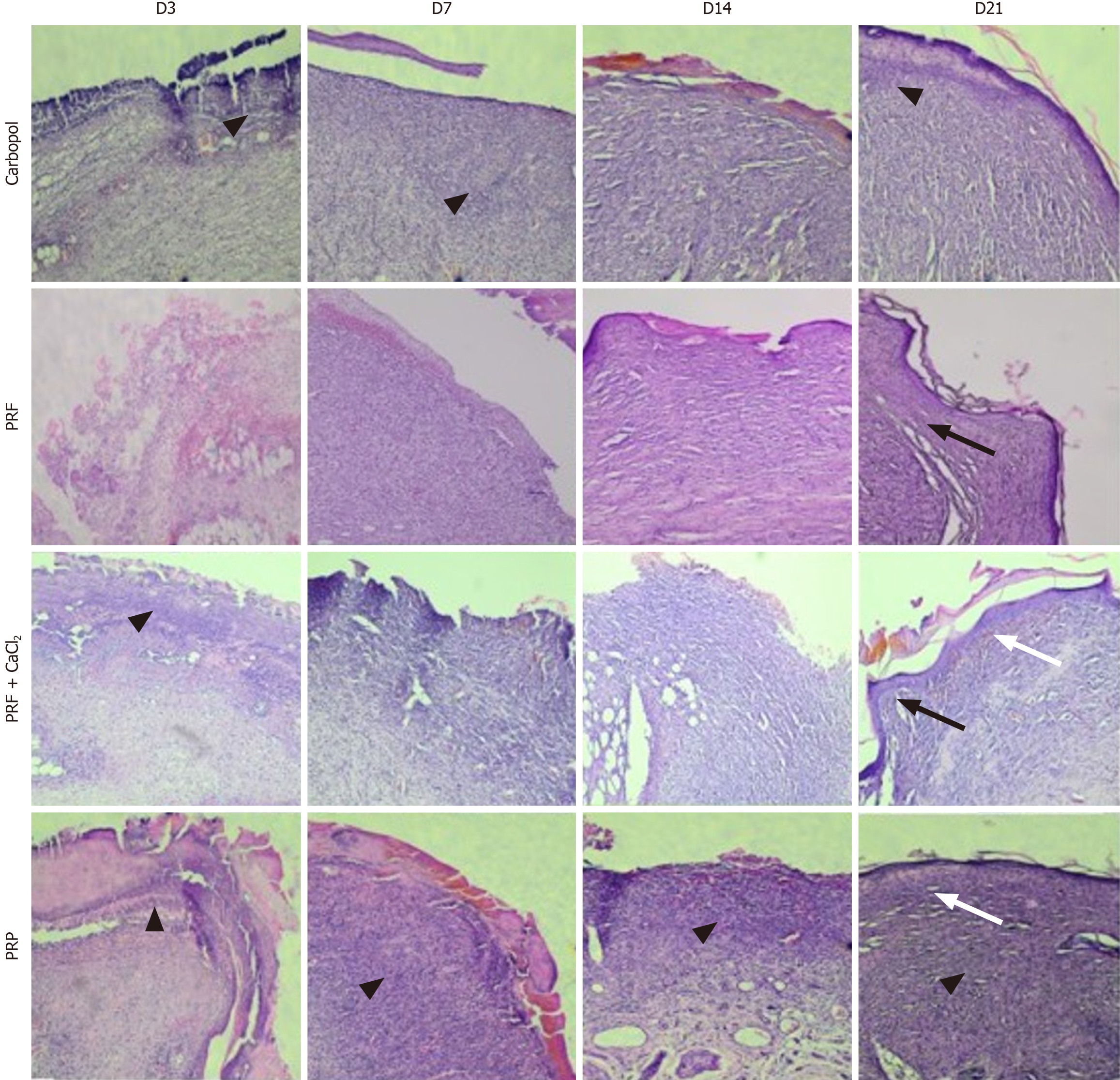

Regarding the presence of collagen (collagenization), on D3, it was either absent or observed in less than 25% of the wound area across all experimental groups, with no statistical differences between them. From D3 to D7, the presence of collagen increased, and starting from D7, there was a slight trend of increasing collagenization until D21. On D14, higher collagenization was observed in the PRF group (50%-75% of the wound area-score 3), PRF + CaCl2 group (25%-50%-score 2, and 50%-75%), and PRP group (50%-75%), compared to the Carbopol group (25%-50%), with this difference being significant. By D21, collagenization in the PRF group had increased, observed in 100% (score 4) or 50%-75% of the wound area. Collagenization in this group was significantly higher compared to the Carbopol group (less than 25% or 25%-50% of the wound area) and the PRP group (25%-50% or 50%-75%). Significant differences were also observed between the PRF and PRP groups, and between the PRF + CaCl2 (25%-50% or 50%-75%) and Carbopol groups (Figure 3D). Representative histological images of the skin wounds from the experimental groups during the repair process are shown in Figure 4.

MT stains collagen blue, distinguishing it from cellular elements, which are stained red. The analysis of blue staining intensity was conducted for the Carbopol group, PRF group, PRF + CaCl2 group, and PRP group on D3, D7, D14, and D21. On D3, the staining intensity in all groups was significantly higher compared to the Carbopol group, with the PRF group showing higher collagen content than the PRP group, and the PRP group showing higher content than the PRF + CaCl2 group. From D3 to D7, the blue staining intensity did not seem to increase for the PRF + CaCl2 group, while in the other groups, the staining intensity increased, indicating that the collagen amount was significantly higher in these groups compared to the PRF + CaCl2 group. No significant differences in blue staining intensity were observed between the experimental groups on D14. By D21, collagen intensity appeared to have increased in all experimental groups, being significantly higher in the PRF group compared to the Carbopol and PRP groups (Figure 5).

Inflammation is a fundamental process for tissue regeneration; however, excessive inflammation can impair the development of subsequent phases, such as proliferation and tissue remodeling[14]. Previous studies have shown improvements in the healing process with the use of platelet concentrates, and the beneficial effect appears to be associated with a reduction in inflammation, leading to decreased vascular permeability and edema[15]. Additionally, they stimulate the secretion of growth factors that induce cellular proliferation of fibroblasts, osteoblasts, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and leukocyte migration[16-18].There is evidence showing that PRF has a more significant role in wound healing compared to PRP. PRF provides a continuous and gradual release of growth factors, facilitating more effective clonal expansion and cellular differentiation[19]. Horgos et al[20] demonstrated that patients treated with PRF injections showed a substantial reduction in wound size, which consequently led to a decrease in injury-associated hyperalgesia. PRP combined with CaCl2 results in a more efficient release of growth factors due to more complete platelet activation[21]. In this study, we used CaCl2 in combination with PRF to determine if calcium chloride could positively influence platelet activity. The enhanced inflammatory response caused by the addition of CaCl2, especially in the initial days, may be linked to the modulation of the immune response through calcium-sensitive receptors, inducing a response via the inflammasome complex and activation of the NF-κB pathway[22], which could accelerate the inflammatory phase. In this study, PRF was more effective compared to the Carbopol (control) group in the initial days following wound creation, particularly in terms of wound closure. The efficacy of PRF in the healing process appears to be linked to its architecture, forming a dense fibrin network that captures growth factors secreted by activated platelets, concentrating them at the injury site and facilitating the creation of a microenvironment conducive to tissue repair[23]. The macroscopic analysis of skin wounds revealed the appearance of the wound, with a thick crust firmly adhered or a soft and adhered crust covering the wound. In terms of the type of exudate, on D3, a small exudate was present on groups, probably due to the polarization of the immune response. However, by D7, some animals in all groups showed serosanguinous exudate. The reepithelialization score measures the area of the wound with new epithelial formation, and this score decreases with increased reepithelialization; there was no difference on this parameter. The data from this study suggest an increase in the inflammatory process associated with PRF (D14) and PRP (D21), which could be related to the neoangiogenesis inherent to the wound healing process[24]. Both in vitro and in vivo studies indicate that PRP and PRF are involved in inducing angiogenesis[25,26]. These platelet concentrates, and consequently their granules, including growth factors, show a high capacity to stimulate endothelial proliferation in a coordinated manner, restoring local microvasculature and enabling an optimal blood supply for the recovery process[27,28]. The group of animals treated with PRF + CaCl2 maintained neovascularization until the end of the experiment (Day 21); this could be related to the delayed resolution of the wound, prolonging the natural course of tissue repair. Despite the proven efficacy of PRP in the tissue repair process[8,29], this concentrate did not produce significant results compared to PRF. This may be associated with the pronounced inflammatory process and the local concentration of CaCl2. In this study, we used the methodology described by Lima IN[30], which employs 1.7 mmol/L CaCl2 to activate PRP, a widely used approach in humans. The literature shows a lack of standardization regarding the concentration of CaCl2 used for activating platelet concentrates, with variations including 20 mmol/L[31], 22.8 mmol/L[32], and 901 mmol/L[33]. As described by Chan et al[34], dysregulation of an inflammatory response mediated by T helper 2 (Th2) lymphocytes under excessive conditions can trigger pathological fibrosis with excessive extracellular matrix deposition. In our experiments, we observed a significant increase in collagen deposition and fibroblast proliferation starting from the 14th day. Ridiandries et al[35] stated that an unbalanced response from these mediators tends to prolong the inflammatory phases and impair the natural course of healing. Collagen production is a crucial factor in wound healing, as it provides strength to the tissue. During tissue regeneration, fibroblasts deposit type III collagen, which over time loses water and reorganizes, interweaving to form the more resilient type I collagen[36,37]. In this study, the experimental groups treated with platelet concentrates showed greater collagen deposition compared to the control group. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of PRF in a rabbit model of induced periodontitis, concluding that PRF application is associated with improved collagen density, as evidenced by MT staining at 14 days[38]. According to the results obtained in this study, PRF appears to be effective in negatively modulating the inflammatory phase of the repair process and stimulating neoangiogenesis. Regarding PRP, further studies are needed to elucidate the influence of different concentrations of CaCl2 in its activation. CaCl2 leads to immediate platelet activation, which releases their granules, enhancing the healing response in the initial days of the process[39,40].

This study suggests that PRF-based dressing is a good approach in the initial stages of healing. Wound treatment with PRF significantly affected the size of the lesion, the rate of retraction and allowed better organization of collagen through HE and TM stains. However the group treated with PRF + CaCl2 and PRP demonstrated higher fibroblast proliferation and inflammatory infiltration, which probably culminated in a delay in the healing process. Therefore, PRF can be considered a promising therapeutic approach in wound treatment. Furthermore, the murine model study provides a solid basis for future clinical investigations in humans. However new research is necessary to fully understand the mechanism of action and the mediators involved in PRF and PRP efficacy and safety in clinical trials.

| 1. | Sen CK. Human Wound and Its Burden: Updated 2020 Compendium of Estimates. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2021;10:281-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 581] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 131.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Spira JAO, Borges EL, Júnior JFP, Monteiro DS, Kitagawa KY. Estimated costs in treating sickle cell disease leg ulcer. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2020;54:e03582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim HS, Sun X, Lee JH, Kim HW, Fu X, Leong KW. Advanced drug delivery systems and artificial skin grafts for skin wound healing. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;146:209-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 63.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ferreira LC. Fatores que interferem na produção e características do concentrado sanguíneo - PRF (Fibrina Rica em Plaquetas). Universidade Federal de Uberlândia. Available from: https://repositorio.ufu.br/bitstream/123456789/38031/1/FatoresInterferemProdu%C3%A7%C3%A3o.pdf. |

| 5. | André Hergesel de O. Avaliação do papel da fibrina rica em plaquetas em defeito crítico cirurgicamente criado em calota de ratos induzidos à hipercolesterolemia tratados ou não com atorvastatina. Available from: https://repositorio.unesp.br/items/fcb8e7a2-1cbb-4fec-abcd-dbe27a1c4001. |

| 6. | Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, Gogly B. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e37-e44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 776] [Cited by in RCA: 1017] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Borges SB. Plasma rico em plaquetas de ratos wistar. Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio Mesquita Filho. 2019. |

| 8. | Xu P, Wu Y, Zhou L, Yang Z, Zhang X, Hu X, Yang J, Wang M, Wang B, Luo G, He W, Cheng B. Platelet-rich plasma accelerates skin wound healing by promoting re-epithelialization. Burns Trauma. 2020;8:tkaa028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Harris C, Bates-Jensen B, Parslow N, Raizman R, Singh M, Ketchen R. Bates-Jensen wound assessment tool: pictorial guide validation project. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37:253-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Al-Watban FA, Andres BL. Polychromatic LED therapy in burn healing of non-diabetic and diabetic rats. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2003;21:249-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Oliveira ST, Leme MC, Pippi NL, Raiser AG, Manfron MP. Formulações de confrei (Symphytum officinale L.) na cicatrização de feridas cutâneas em ratos. Rev Fac Zootec, Vet Agro Uruguaiana. 2000;7:61-65. |

| 12. | Garros Ide C, Campos AC, Tâmbara EM, Tenório SB, Torres OJ, Agulham MA, Araújo AC, Santis-Isolan PM, Oliveira RM, Arruda EC. [Extract from Passiflora edulis on the healing of open wounds in rats: morphometric and histological study]. Acta Cir Bras. 2006;21 Suppl 3:55-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Coleman R. Picrosirius red staining revisited. Acta Histochem. 2011;113:231-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang Z, Qi F, Luo H, Xu G, Wang D. Inflammatory Microenvironment of Skin Wounds. Front Immunol. 2022;13:789274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Trybek G, Rydlińska J, Aniko-Włodarczyk M, Jaroń A. Effect of Platelet-Rich Fibrin Application on Non-Infectious Complications after Surgical Extraction of Impacted Mandibular Third Molars. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dallosto JZ, Souza MA, Prado LDS, Siqueira LO. Analysis of different platelet-rich fibrin processing. Rev odontol UNESP. 2022;51. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fan Y, Perez K, Dym H. Clinical Uses of Platelet-Rich Fibrin in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Dent Clin North Am. 2020;64:291-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Alrayyes Y, Aloraini S, Alkhalaf A, Aljasser R. Soft-Tissue Healing Assessment after Extraction and Socket Preservation Using Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF) in Smokers: A Single-Blinded, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Feigin K, Shope B. Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma and Platelet-Rich Fibrin in Dentistry and Oral Surgery: Introduction and Review of the Literature. J Vet Dent. 2019;36:109-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Horgos MS, Pop OL, Sandor M, Borza IL, Negrean RA, Cote A, Neamtu AA, Grierosu C, Sachelarie L, Huniadi A. Platelets Rich Plasma (PRP) Procedure in the Healing of Atonic Wounds. J Clin Med. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hamilton B, Tol JL, Knez W, Chalabi H. Exercise and the platelet activator calcium chloride both influence the growth factor content of platelet-rich plasma (PRP): overlooked biochemical factors that could influence PRP treatment. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:957-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Iamartino L, Brandi ML. The calcium-sensing receptor in inflammation: Recent updates. Front Physiol. 2022;13: 1059369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Takamori ER, Teixeira MVT, Menezes K, Carias RBV, Borojevic R. Fibrina rica em plaquetas: preparo, definição da qualidade, uso clínico. Visa em Debate. 2018;6:118. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Eming SA, Krieg T, Davidson JM. Inflammation in wound repair: molecular and cellular mechanisms. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:514-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1356] [Cited by in RCA: 1473] [Article Influence: 81.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gomez TW, Gopal RV, Gaffoor FMA, Kumar STR, Girish CS, Prakash R. Comparative evaluation of angiogenesis using a novel platelet-rich product: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2019;22:23-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Naji JM. Efficacy of Platelet Rich Fibrin on Angiogenesis. J Duhok University. 2020;23. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Berndt S, Carpentier G, Turzi A, Borlat F, Cuendet M, Modarressi A. Angiogenesis Is Differentially Modulated by Platelet-Derived Products. Biomedicines. 2021;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Everts PA, Lana JF, Onishi K, Buford D, Peng J, Mahmood A, Fonseca LF, van Zundert A, Podesta L. Angiogenesis and Tissue Repair Depend on Platelet Dosing and Bioformulation Strategies Following Orthobiological Platelet-Rich Plasma Procedures: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines. 2023;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Inbarajan A, Veeravalli PT, Seenivasan MK, Natarajan S, Sathiamurthy A, Ahmed SR, Vaidyanathan AK. Platelet-Rich Plasma and Platelet-Rich Fibrin as a Regenerative Tool. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2021;13:S1266-S1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lima GATD. Efeito de polissacarídeos de algas marinhas na agregação plaquetária e coagulação plasmática. Available from: https://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/UFF-2_06d3940daea2aa0e8b51d8922ffb8dcb. |

| 31. | Cavallo C, Roffi A, Grigolo B, Mariani E, Pratelli L, Merli G, Kon E, Marcacci M, Filardo G. Platelet-Rich Plasma: The Choice of Activation Method Affects the Release of Bioactive Molecules. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:6591717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Murlistyarini S, Aninda LP, Afridafaz UA, Widyarti S, Endharti AT, Sardjono TW. The combination of ADSCs and 10% PRP increases Rb protein expression on senescent human dermal fibroblasts. F1000Res. 2021;10:516. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Zheng C, Zhu Q, Liu X, Huang X, He C, Jiang L, Quan D, Zhou X, Zhu Z. Effect of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) concentration on proliferation, neurotrophic function and migration of Schwann cells in vitro. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016;10:428-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chan AJ, Jang JC, Nair MG. Tissue Remodeling and Repair During Type 2 Inflammation. The Th2 Type Immune Response in Health and Disease. New York: United States: Springer, 2016. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Ridiandries A, Tan JTM, Bursill CA. The Role of Chemokines in Wound Healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Valencia KF. Aplicação de proteínas toleradas por via subcutânea ou tópica melhora a cicatrização de feridas cutâneas em camundongos. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. 2020. Available from: https://repositorio.ufmg.br/handle/1843/32894. |

| 37. | Morgan NH, Arakeep HM, Haiba DA, Aboelgoud MA. Role of Masson’s trichrome stain in evaluating the effect of platelet-rich plasma on collagenesis after induction of thermal burn in adult male albino rats. Tanta Med J. 2022;50:86-93. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Nasution AH, Dewanti W. Efficacy of platelet-rich fibrin application for improving collagen density of gingival connective tissue in periodontitis-induced rabbits. Padjadjaran J Dent. 2022;34:41. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | He L, Lin Y, Hu X, Zhang Y, Wu H. A comparative study of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on the effect of proliferation and differentiation of rat osteoblasts in vitro. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:707-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Mijiritsky E, Assaf HD, Peleg O, Shacham M, Cerroni L, Mangani L. Use of PRP, PRF and CGF in Periodontal Regeneration and Facial Rejuvenation-A Narrative Review. Biology (Basel). 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |