Published online Oct 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i10.685

Peer-review started: May 11, 2016

First decision: June 14, 2016

Revised: August 4, 2016

Accepted: August 15, 2016

Article in press: August 16, 2016

Published online: October 27, 2016

Processing time: 169 Days and 15.5 Hours

To analyse the range of histopathology detected in the largest published United Kingdom series of cholecystectomy specimens and to evaluate the rational for selective histopathological analysis.

Incidental gallbladder malignancy is rare in the United Kingdom with recent literature supporting selective histological assessment of gallbladders after routine cholecystectomy. All cholecystectomy gallbladder specimens examined by the histopathology department at our hospital during a five year period between March 2008 and March 2013 were retrospectively analysed. Further data was collected on all specimens demonstrating carcinoma, dysplasia and polypoid growths.

The study included 4027 patients. The majority (97%) of specimens exhibited gallstone or cholecystitis related disease. Polyps were demonstrated in 44 (1.09%), the majority of which were cholesterol based (41/44). Dysplasia, ranging from low to multifocal high-grade was demonstrated in 55 (1.37%). Incidental primary gallbladder adenocarcinoma was detected in 6 specimens (0.15%, 5 female and 1 male), and a single gallbladder revealed carcinoma in situ (0.02%). This large single centre study demonstrated a full range of gallbladder disease from cholecystectomy specimens, including more than 1% neoplastic histology and two cases of macroscopically occult gallbladder malignancies.

Routine histological evaluation of all elective and emergency cholecystectomies is justified in a United Kingdom population as selective analysis has potential to miss potentially curable life threatening pathology.

Core tip: The selective use of histopahological examination of gallbladders removed during routine cholecystectomy has been advocated by several authors in the literature. We present a large single centre study demonstrating a full range of gallbladder disease from cholecystectomy specimens, including more than 1% neoplastic histology and two cases of microscopic gallbladder malignancies in macroscopically normal gallbladders. On this basis, routine histological evaluation of all elective and emergency cholecystectomies is justified in an United Kingdom population as selective analysis has potential to miss potentially curable life threatening pathology.

- Citation: Patel K, Dajani K, Iype S, Chatzizacharias NA, Vickramarajah S, Singh P, Davies S, Brais R, Liau SS, Harper S, Jah A, Praseedom RK, Huguet EL. Incidental non-benign gallbladder histopathology after cholecystectomy in an United Kingdom population: Need for routine histological analysis? World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(10): 685-692

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i10/685.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i10.685

Cholecystectomy is among the most commonly performed surgical procedures worldwide, principally indicated in patients with symptomatic gallstone-associated disease. Approximately 5.5 million people in the United Kingdom have gallstones[1], with 70000 undergoing operative intervention each year in the United Kingdom[2]. The indication for cholecystectomy is usually benign disease, though the histology can reveal incidental premalignant or malignant gallbladder pathology warranting appropriate further surgical resection.

Incidental gallbladder malignancies are rare in the United Kingdom with reported rates between 0.17%-0.81% of cholecystectomy resected specimens[3-6]. Further revision surgery with curative intent is generally indicated in those without metastatic disease and tumour staging worse than T1a. Potentially curative resection may be offered in up to 50% of patients with incidental gallbladder malignancy post-cholecystectomy, however, some of these patients are ultimately found to have unresectable or metastatic disease at the time of laparotomy[7,8].

Recognised premalignant conditions leading to gallbladder carcinoma include gallbladder dysplasia and those arising from adenomatous polyps[9]. Dysplastic changes are often difficult to predict pre-operatively due to absence of macroscopic abnormalities detectable on imaging, hence emphasizing need to histologically examine all gallbladders resected[9]. Strategies for gallbladder polyp surveillance and indications for operative management have been previously recommended, however this remains a controversial topic with widely varied practice in reality[10,11].

Some authors have advocated selective, rather than routine, histopathological analysis of resected gallbladders, primarily due to rarity of incidental disease, financial implications and time burden on histopathology departments[4-6,12]. Others have suggested macroscopic examination of resected gallbladders intra-operatively, to determine whether further histological analysis is required depending on presence of suspicious macroscopic lesions or significant patient risk factors for gallbladder cancer[4].

The primary aim of this study was to review the range of histopathology detected in the largest United Kingdom series of routine cholecystectomy specimens from a single centre teaching hospital, in particular pre-malignant and malignant pathology. Secondary aims were to further analyse patients with incidental gallbladder malignancy, dysplasia and polyps and to make recommendations for future practice and necessity of routine histological examination of gallbladder specimens.

This descriptive study was designed as a retrospective review of a database of all gallbladder specimens histopathologically examined at Cambridge University Hospital (Cambridge, United Kingdom) during a five year period between March 2008 and March 2013. This hospital is a tertiary referral centre for management of hepatopancreatobiliary malignancies. Exclusion criteria included gallbladders resected as part of another procedure (e.g., Whipple’s resection) and instances where malignancy was strongly suspected pre-operatively, including ultrasonographically suspicious lesions or polyps greater than 1 cm in size. Histology reports were retrospectively analysed for presence of gallbladder disease, including benign and malignant pathology.

Further information was obtained on gallbladders demonstrating incidental gallbladder malignancies, dysplastic changes and polypoid structures including patient demographics, pre-operative symptoms and imaging, operative details, tumour histology and postoperative clinical outcomes. In patients with incidental malignancies, extensive data was collected on staging, tumour type, further resectional surgery and survival time. Survival times were calculated from time of cholecystectomy to date of death or latest follow up. In those with detected dysplasia, additional data were collected, including type of dysplasia, presence of tumour foci and associated risk factors (e.g., primary sclerosing cholangitis). For gallbladder specimens containing polyps, further information was obtained including uptake into our gallbladder surveillance programme, polyp type, size and number, preoperative ultrasonography findings and indications for surgery. Hospital electronic medical records and patient hard copy notes were used to extract relevant data.

Statistical analysis were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Windows Version 22.0, Chicago, IL, United States) with a P-value less than 0.05 representing statistical significance. Continuous data analysed was described with median values accompanied with ranges [Median (range)].

A total of 4027 resected gallbladders from elective and emergency cholecystectomies were examined by the histopathology department at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in the 5 years period studied. Overall, we report an incidental gallbladder invasive adenocarcinoma rate of 0.15% (6/4027) and one gallbladder demonstrating carcinoma-in-situ (0.02%, 1/4027). The majority of resected specimens exhibited gallstone or cholecystitis related disease. Table 1 displays the range of histopathological findings demonstrated from our patient sample.

| Histology | Subgroup | No (n = 4027) | % Total |

| Normal | 182 | 4.50% | |

| Cholecystitis | 3480 | 86.3% | |

| Acute | 45 | ||

| Chronic | Gangrenous | 3435 | |

| Empyema | 29 | ||

| Follicular | 6 | ||

| Xanthogranulomatous | 3 | ||

| 5 | |||

| Cholesterosis | 246 | 6% | |

| Polypoidal Lesion | 44 | 10% | |

| Cholesterol-based | 42 | ||

| Hyperplastic | 1 | ||

| Adenoma | 1 | ||

| Metaplasia | 13 | 0.3% | |

| Dysplasia | 55 | 1.4% | |

| Focal LGD* | 40 | ||

| Multi-Focal LGD | 9 | ||

| Focal HGD | 2 | ||

| Multi-focal HGD | 4 | ||

| (Multi-focal HGD + AC) | (2) | ||

| Carcinoma in situ | 1 | 0.02% | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 6 | 0.15% |

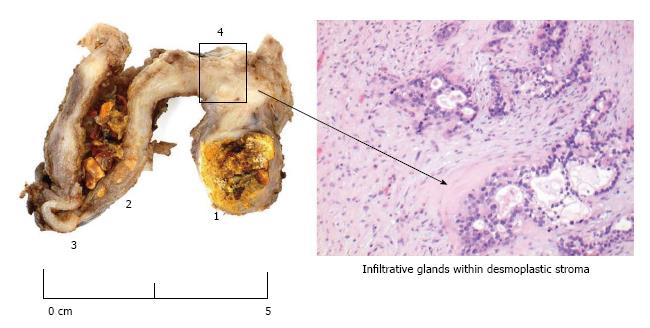

Primary invasive gallbladder adenocarcinoma was identified in 6 patients with a median age of 66.5 years (range 45-71) and a female majority (5/6) (Figure 1 is an illustration of typical macroscopic and microscopic appearances of a gallbladder cancer specimen). All but one patient (5/6) had co-existing cholelithiasis on pre-operative ultrasonography, while half (3/6) had ultrasonography evident thickened gallbladder walls consistent with cholecystitis. All patients were symptomatic with right upper quadrant pain pre-operatively, however none presented with a palpable mass, clinical jaundice or weight loss. In none of these patients was gallbladder malignancy considered a potential differential diagnosis on decision to perform a cholecystectomy. Surgery in 4 of these of these cases were reported as more challenging than usual, but not in the other 2, which were both reported as macroscopically normal from histopathological examination, but microscopic examination revealed T1 disease, one T1a and the other T1b. Otherwise, tumour staging varied significantly with T3 disease the most advanced. To present date, 3 patients have died from progressive metastatic disease with a post-cholecystectomy mean survival time of 20.6 mo.

A single case of carcinoma-in-situ (0.02%, 1/4027) was identified in a 66-year-old gentleman with known gallstones. No lesion was identified on macroscopic examination, however microscopic analysis revealed foci of adenocarcinoma within surrounding extensive high grade dysplasia. Further details of all carcinoma patients including operation details and clinical outcome postoperatively are depicted in Table 2.

| Age | Sex | Pre-operative imaging | Operation details | Operative findings | Tumour type/staging | Further management | Survival (mo) |

| 71 | F | USS: Multiple gallstones | Lap | Smooth GB wall with multiple calculi | T1a N0 M0, Adenocarcinoma | No further operation, surveillance CT scans | Alive (64) |

| 68 | F | USS: Multiple stones, dilated CBD; CT: Multiple stones, no mass seen | Open | Large GB calculi, no CBD stones on CBD exploration | T2 N0 M0, Adenocarcinoma (MD) | Not fit for further resection (known chronic leukaemia – already on chemotherapy) | Alive (22) |

| 45 | F | USS: Stones, thickened GB wall; CT: Inflammatory changes on GB wall | Lap converted to open | Small abscess on GB bed, gross GB wall thickening | T3 N1 M0, Adenocarcinoma (PD) | Revision operation – abandoned as nodules on umbilical port and peritoneum, palliative chemotherapy | 12 |

| 70 | F | USS: Grossly thickened GB wall and multiple gallstones | Lap | Thick dense adhesions with fistulous communication between GB tumour and transverse colon | T3 N1 M1, Adenocarcinoma (PD) | Chemotherapy | 12 |

| 65 | F | USS: Stones, cholecystitis; CT: Marked GB wall thickening, ?cholecystitis | Lap | GB wall inflamed, disintegrated with biliary spillage++ | T2 N0 M0, Adenocarcinoma (MD) | Not medically fit for revision surgery; developed nodal disease but not fit for chemo; palliative therapy | 37 |

| 65 | M | USS: Sludge and gallstones (pancreatitis patient) | Lap | Mildly inflamed GB with calculi | T1b N0 M0, Adenocarcinoma (PD) | Revision surgery and lymphadenectomy, chemotherapy | Alive (36) |

| 66 | M | USS: Multiple small gallstones | Lap | Smooth GB wall with calculi | Tis N0 M0 | No further management | Alive (54) |

The overall incidence rate of gallbladder dysplasia was 1.37% (55/4027) with a wide spectrum of dysplastic changes as illustrated in Table 1. Median age was 53 years (range 22-82) with the majority of patients being female (85.5%, 47/55). From all 55 cases of dysplasia, 47.3% (26/55) had co-existing gallstone disease on final histology. Primary sclerosing cholangitis was pre-existent in 3.6% (2/55) patients. Four gallbladders exhibited multifocal high grade dysplasia from which half (2/4) exhibited foci of adenocarcinoma, both previously mentioned in our cancer cohort (Table 2). One gallbladder (1.8%, 1/55) demonstrated a tubular adenoma with surrounding focal high grade dysplastic changes. No gallbladder specimen revealed evidence of dysplasia at the cystic duct resection margin.

Gallbladder polyps were identified in 1.09% (44/4027). The median age was 51 years (range 28-84). Pre-operative imaging identified 77.3% (34/44) of these polyps, with a measured median size of 7.4 mm (range 2-13 mm). All but three polyps were cholesterol in nature (93.2%, 41/44). The other three polyps varied in histology including one hyperplastic polyp, one xanthomatous polyp and one tubular adenomatous polyp. None of these polyps exhibited malignant features.

This study is the largest United Kingdom series to date evaluating range of histopathology demonstrated from cholecystectomy resected gallbladder specimens. Our main findings include observed overall rates of 0.17% incidental gallbladder adenocarcinomas and 1.37% incidental premalignant gallbladder dysplasia. The most common histology reported in our study was chronic cholecystitis (85.3%).

Incidental gallbladder malignancy identified in cholecystectomy specimens make up the majority of all diagnosed gallbladder cancers[12]. There is a well-documented heterogeneity in the incidence of gallbladder cancer, varying according to various patient demographic factors including worldwide location, ethnicity and age[13]. Along with most of Europe, the United Kingdom is considered a low risk area with an associated low rate of incidental gallbladder malignancies when compared to high risk areas such as India and Japan[14]. Previous United Kingdom studies have reported incidence rates between 0.17%-0.81%, however some of these studies have included gallbladders in which tumour was suspected on preoperative imaging[3-6]. Our study observed a 0.17% rate of incidental gallbladder malignancies. This relatively low incidence may reflect the ethnicity of our study population with a strong European-Caucasian representation as only one patient from all carcinoma and dysplasia-revealing gallbladders was non-Caucasian in ethnicity (Indian). Furthermore, those patients in whom gallbladder malignancy was strongly suspected on pre-operative imaging were strictly excluded from our study and this may have contributed further to the low incidence rate.

Chronic gallstone-related irritation is a known significant risk factor for dysplastic changes and development of carcinoma[15]. Increased gallstone weight, number and volume have also been associated with an increased risk of gallbladder cancer[16]. In this study, 6 out of the 7 carcinoma patients had co-existing gallstones.

In contrast, only 47.3% of dysplastic gallbladders demonstrated final histology cholelithiasis, perhaps implying other pathogenesis factors involved in development of gallbladder dysplasia. In this regard, 2 patients exhibiting high grade dysplasia had a pre-operative diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis, a known risk factor for gallbladder malignancy with previous reports of up to 30% of resected gallbladders displaying dysplasia/carcinoma pathology[17]. Consistent with this, our policy is to adopt a low threshold in recommending cholecystectomy in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis presenting with clinical or radiological evidence of gallbladder pathology.

In our institution, routine pre-operative investigations for patients presenting with symptomatic biliary pathology includes the assessment of liver function tests alongside ultrasonographic assessment of the gallbladder and biliary tree. Should these provide any suspicious features then further assessment with cross sectional imaging (CT scan or MRCP) and endoscopic ultrasound are performed, followed by discussion in the regional multi-disciplinary meeting where decision on further management is made.

Six patients in our cohort were identified as having gallbladder carcinoma on post-operative histology (Table 2), with a median age of 66.5 years. The youngest patient was a 45-year-old female who was found to have T3N1 disease which progressed rapidly with peritoneal spread. None of these were suspected pre-operatively. In 2 of the 6 cases, the pre-operative ultrasound identified gallstones within a thin walled gallbladder with the absence of any worrying features to necessitate further investigations. Operative findings for these 2 cases were of thin walled gallbladders (macroscopically normal) and hence gallbladder cancer was not suspected. Post-operative histology described early gallbladder carcinoma (T1a and T1b respectively), despite these microscopic findings, the histopathological examination reported these specimens as macroscopically normal looking. The remaining 4 cases, were identified on pre- and intra-operative examinations as having macroscopic abnormalities. In 3 of these cases, further pre-operative investigations with cross sectional imaging (CT scan) were performed. The CT findings were reported as inflammatory, with the absence of a mass lesion and abnormal lymphadenopathy. Operative findings were of thickened gallbladder walls, while one had an associated abscess in the gallbladder fossa. The clinical suspicion here was of severe inflammatory changes. Although the presence of gallbladder cancer in such cases is always a possibility, the clinical suspicion was low and hence standard cholecystectomy was performed. Post-operative histology identified T2 disease in 2 cases and T3 N1 disease in the remaining case.

The final case was of a 70-year-old female with pre-operative ultrasonography describing a thickened and inflamed gallbladder with calculi; at the time of surgery she was found to have dense adhesions a thickened shrunken gallbladder, as well as a fistulous communication between the gallbladder and the transverse colon. These findings were thought to be inflammatory in nature, however, the diagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma is regarded as a possibility in such cases. An intra-operative decision on whether a simple cholecystectomy or a more radical should be taken. The majority of such cases will ultimately prove to be benign and inflammatory in aetiology. Factors such as pre-operative co-morbidities and the potential stage of disease, should this turn out to be malignant, are taken into account. If clinical suspicion of cancer is high, co-morbidities are limited and the patient is suitable for a potentially curative resection, then frozen section may be performed to confirm the diagnosis and the surgical plan amended as deemed necessary. However, if the patient or tumour factors render potentially curative surgical intervention impossible then a standard cholecystectomy to achieve a tissue diagnosis may be deemed appropriate.

Several United Kingdom papers have recommended selective histopathological analysis of cholecystectomy resected specimens[4-6,14]. This recommendation is based on the assumption that incidental gall bladder malignancy is associated with macroscopic lesions which can be identified on examination of the resected gall bladder in the operating theatre. Our study, the largest United Kingdom series to date and the only one with over 3000 patients, demonstrates that this assumption is not reliable, as evidenced by the finding of gallbladder malignancy in macroscopically normal gallbladders, including T1b disease for which revision surgery is generally advocated, on account of published data showing a survival benefit of 3.4 years from radical resection over simple cholecystectomy[18]. The patient with T1b disease underwent further liver segmental resection with lymphadenectomy and is disease free three years later to this day. This is the first United Kingdom series to report a patient with macroscopically occult incidental gallbladder malignancy with no preoperative or intra-operative suspicion of carcinoma who subsequently underwent successful R0 resectional surgery.

A systematic review in 2014 by Jamal et al[14] examined 20 previous studies, including 6 United Kingdom studies, evaluating the necessity of routine histological analysis in macroscopically normal gallbladders. The authors concluded that in gallbladders deemed normal from macroscopic examination by the operating surgeon, selective histological analysis was feasible in the “low risk” European ethnicity under the age of 60[14]. However, the systematic review did not include a recent histopathology paper by Hayes et al[19] examining gallbladder specimens sent for histology after cholecystectomy. This study reported a striking 50% (5/10) of incidental invasive gallbladder malignancies presenting with no macroscopic abnormalities on histopathologist examination with a mean age of 54.6 years. This proportion of macroscopically occult malignancies in a “low risk” population of that age range challenges the recommendations from Jamal et al[14] recent systematic review. In addition, United Kingdom Royal College of Pathologists 2005 recommendations state that all gallbladders removed for presumed benign disease warrant histological examination in order to ensure no significant subtle pathology is missed from macroscopic examination[20].

Solaini et al[3] in 2014 reported almost 3% incidental neoplastic findings from cholecystectomy gallbladders with inclusion of dysplastic changes and is one of few United Kingdom papers supporting routine histological analysis of all gallbladder specimens. The authors reported dysplasia rates of 2.3% (18/771) with a median age of 45 years in a population with strong Asian ethnicity representation (66%). Our study observed lower rates of dysplastic changes at 1.37% (55/4027) with a higher median age of 53 years, perhaps partly explained by the lack of representation of the Asian population in our study group[21].

Whether the finding of dysplasia is of clinical significance may be debated, but our opinion is that this is not merely academic. Positive cystic duct margins and gross high grade dysplastic changes can indicate further potential pancreatobiliary disease, with further operative exploration warranted in certain circumstances. Bickenbach et al[22] in 2011 reported five cases of high grade dysplasia at the cystic duct resectional margin following cholecystectomy, all of whom subsequently underwent further resectional surgery, either with excision of cystic duct remnant or excision of extrahepatic bile duct. Of these, one patient was found to have adenocarcinoma within the resected cystic duct remnant. No gallbladders in our study demonstrated cystic duct margin positive disease, however half our cases of multifocal high grade dysplasia had associated foci of adenocarcinoma. In our practice, the finding of high grade dysplasia on the cystic duct margin would warrant further surgical exploration and frozen section of cystic duct margin to ascertain whether further radical resection would be required to ensure R0 resection.

Gallbladder polyps are common with a reported incidence rate in a recent multi-ethnic United Kingdom series of 3.3%, with higher rates observed in the Asian ethnic groups[23]. Our series reports a 1.09% (44/4027) incidence of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder, however we excluded all polyps reported as sonographically suspicious of malignancy or more than 1 cm in size pre-study in order to focus on incidental gallbladder pathology. Our largely Caucasian study population may also reflect the observed lower polyp incidence rate. All but one polyp demonstrated benign pseudotumour characteristics, predominantly cholesterol in nature (41/44). We did however observe one true polyp adenoma (1/44, 2.3%) occurring in a 67-year-old male and of 3mm in size, which had been reported as a gallstone on preoperative sonography with biliary colic as indication for surgery. Cairns et al[24] in 2013 examined a large cohort of gallbladder polyps in a United Kingdom population and observed a similar 2.2% incidence rate of adenomas as well as 0.7% adenocarcinoma rate. Although adenomas are histologically benign, there is a well-recognised adenoma-carcinoma path of carcinogenesis to gallbladder malignancy[21]. This has led to polyp surveillance implementation in HPB centres with indications to operatively remove gallbladders displaying polypoid lesions above 1 cm, rapidly growing in size or symptomatic in nature[24]. Marangoni et al[10] surveyed United Kingdom surgeons regarding their practice of gallbladder polyp surveillance with indications for operative management and revealed significant variation and identified a need for formal national guidelines to tackle this area of conflicting opinions. Although polyp surveillance was not analysed in further detail as part of this study, it is our practice to actively monitor polyps with ultrasonography particularly with recent literature to support it is cost effective[24].

In conclusion, our study has demonstrated a broad spectrum of histopathology from examination of cholecystectomy resected gallbladders for preoperatively diagnosed benign gallbladder disease. This is the largest United Kingdom series within the literature and observed 0.17% incidence of primary adenocarcinoma and 1.37% gallbladder dysplasia. The study is the first United Kingdom study to report cases of macroscopically normal gallbladders harbouring adenocarcinoma lesions with subsequent successful R0 resection. We also report a single case of adenocarcinoma in a patient aged 45 years. With over 1% rate of pre-malignant and malignant disease, we conclude that routine histological evaluation of all elective and emergency cholecystectomies is justified in a United Kingdom population and that selective histological evaluation has the potential to miss life threatening gallbladder pathology amenable to subsequent curative surgery.

Cholecystectomy is among the most commonly performed surgical procedures worldwide. Routine histopathological examination of the resected specimens is usually performed. However, selective histopathological analysis has been proposed in the literature, primarily due to rarity of incidental disease (0.17%-0.81% in the United Kingdom), financial implications and time burden on histopathology departments.

The authors aimed to analyse the range of histopathology detected in the largest published United Kingdom series of cholecystectomy specimens and to evaluate the rational for selective histopathological analysis.

This large single centre study demonstrated a full range of gallbladder disease from cholecystectomy specimens, including more than 1% neoplastic histology and two cases of macroscopically occult gallbladder malignancies.

Routine histological evaluation of all elective and emergency cholecystectomies is justified in a United Kingdom population as selective analysis has potential to miss potentially curable life threatening pathology.

The authors described an incidental non-benign gallbladder histopathology after cholecystectomy in a United Kingdom population. More than 4000 cases of resected gallbladder specimens were analyzed histopathologically. Although several reports regarding incidental gallbladder cancer have been already published from high prevalence areas, studies from infrequent area such as the United Kingdom are worth publishing.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Barreto S, Kai K, Tsuchida A S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Brazzelli M, Cruickshank M, Kilonzo M, Ahmed I, Stewart F, McNamee P, Elders A, Fraser C, Avenell A, Ramsay C. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cholecystectomy compared with observation/conservative management for preventing recurrent symptoms and complications in adults presenting with uncomplicated symptomatic gallstones or cholecystitis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18:1-101, v-vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Beckingham IJ. ABC of diseases of liver, pancreas, and biliary system. Gallstone disease. BMJ. 2001;322:91-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Solaini L, Sharma A, Watt J, Iosifidou S, Chin Aleong JA, Kocher HM. Predictive factors for incidental gallbladder dysplasia and carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2014;189:17-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Darmas B, Mahmud S, Abbas A, Baker AL. Is there any justification for the routine histological examination of straightforward cholecystectomy specimens? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:238-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Taylor HW, Huang JK. ‘Routine’ pathological examination of the gallbladder is a futile exercise. Br J Surg. 1998;85:208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bazoua G, Hamza N, Lazim T. Do we need histology for a normal-looking gallbladder? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:564-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Misra MC, Guleria S. Management of cancer gallbladder found as a surprise on a resected gallbladder specimen. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:690-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yip VS, Gomez D, Brown S, Byrne C, White D, Fenwick SW, Poston GJ, Malik HZ. Management of incidental and suspicious gallbladder cancer: focus on early referral to a tertiary centre. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:641-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goldin RD, Roa JC. Gallbladder cancer: a morphological and molecular update. Histopathology. 2009;55:218-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marangoni G, Hakeem A, Toogood GJ, Lodge JP, Prasad KR. Treatment and surveillance of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder in the United Kingdom. HPB (Oxford). 2012;14:435-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Boulton RA, Adams DH. Gallbladder polyps: when to wait and when to act. Lancet. 1997;349:817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Oommen CM, Prakash A, Cooper JC. Routine histology of cholecystectomy specimens is unnecessary. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:738, author reply 738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1591-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jamal K, Ratansingham K, Siddique M, Nehra D. Routine histological analysis of a macroscopically normal gallbladder--a review of the literature. Int J Surg. 2014;12:958-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sheth S, Bedford A, Chopra S. Primary gallbladder cancer: recognition of risk factors and the role of prophylactic cholecystectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1402-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Roa I, Ibacache G, Roa J, Araya J, de Aretxabala X, Muñoz S. Gallstones and gallbladder cancer-volume and weight of gallstones are associated with gallbladder cancer: a case-control study. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:624-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Said K, Glaumann H, Björnstedt M, Bergquist A. The value of thioredoxin family proteins and proliferation markers in dysplastic and malignant gallbladders in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1163-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Abramson MA, Pandharipande P, Ruan D, Gold JS, Whang EE. Radical resection for T1b gallbladder cancer: a decision analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11:656-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Hayes BD, Muldoon C. Seek and ye shall find: the importance of careful macroscopic examination and thorough sampling in 2522 cholecystectomy specimens. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2014;18:181-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Royal College of Pathologists. Histopathology and cytopathology of limited or no clinical value. London: RCPath 2005; 1-13. |

| 21. | Lee SH, Lee DS, You IY, Jeon WJ, Park SM, Youn SJ, Choi JW, Sung R. [Histopathologic analysis of adenoma and adenoma-related lesions of the gallbladder]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55:119-126. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Bickenbach KA, Shia J, Klimstra DS, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Kingham TP, Allen PJ, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica MI. High-grade dysplasia of the cystic duct margin in the absence of malignancy after cholecystectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:865-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Aldouri AQ, Malik HZ, Waytt J, Khan S, Ranganathan K, Kummaraganti S, Hamilton W, Dexter S, Menon K, Lodge JP. The risk of gallbladder cancer from polyps in a large multiethnic series. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:48-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cairns V, Neal CP, Dennison AR, Garcea G. Risk and Cost-effectiveness of Surveillance Followed by Cholecystectomy for Gallbladder Polyps. Arch Surg. 2012;147:1078-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |