Published online Apr 27, 2013. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v5.i4.97

Revised: January 25, 2013

Accepted: February 5, 2013

Published online: April 27, 2013

Processing time: 140 Days and 13.3 Hours

AIM: To prospectively analyse the clinical, biochemical and radiological characteristics of the mass lesions arising in a background of chronic calcific pancreatitis (CCP).

METHODS: Eighty three patients, who presented with chronic pancreatitis (CP) and a mass lesion in the head of pancreas between February 2005 and December 2011, were included in the study. Patients who were identified to have malignancy underwent Whipple’s procedure and patients whose investigations were suggestive of a benign lesion underwent Frey’s procedure. Student t-test was used to compare the mean values of imaging findings [common bile duct (CBD), main pancreatic duct (MPD) size] and laboratory data [Serum bilirubin, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9)] between the groups. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC curve) analysis was done to calculate the cutoff valves of serum bilirubin, CA 19-9, MPD and CBD size. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive valve (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated using these cut off points. Multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression model.

RESULTS: The study included 56 men (67.5%) and 27 women (32.5%). Sixty (72.3%) patients had tropical calcific pancreatitis and 23 (27.7%) had alcohol related CCP. Histologically, it was confirmed that 55 (66.3%) of the 83 patients had an inflammatory head mass and 28 (33.7%) had a malignant head mass. The mean age of individuals with benign inflammatory mass and those with malignant mass was 38.4 years and 45 years respectively. Significant clinical features that predicted a malignant head mass in CP were presence of a head mass in CCP of tropics, old age, jaundice, sudden worsening abdominal pain, gastric outlet obstruction and significant weight loss (P≤ 0.05). The ROC curve analysis showed a cut off value of 5.8 mg/dL for serum bilirubin, 127 U/mL for CA 19-9, 11.5 mm for MPD size and 14.5 mm for CBD size.

CONCLUSION: Elevated Serum bilirubin and CA 19-9, and dilated MPD and CBD were useful in predicting malignancy in patients with CCP and head mass.

- Citation: Perumal S, Palaniappan R, Pillai SA, Velayutham V, Sathyanesan J. Predictors of malignancy in chronic calcific pancreatitis with head mass. World J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 5(4): 97-103

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v5/i4/97.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v5.i4.97

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is characterized by irreversible destruction and fibrosis of exocrine parenchyma, leading to exocrine insufficiency and progressive endocrine failure resulting in diabetes. Alcoholic chronic pancreatitis (ACP) is the commonest type in the western world accounting for 80% of patients[1], whereas in the tropics there is a distinct form of non alcoholic type of CP called tropical calcific pancreatitis (TCP). The features of TCP include younger age of onset, presence of large intraductal calculi, an accelerated course of disease leading to end points of diabetes or steatorrhea and a high susceptibility to pancreatic cancer[2].

The most common cause of a head mass in CP is inflammatory and occurs as a result of defective restitution after recurrent attacks of acute pancreatitis[3]. Inflammatory mass in the head of pancreas is observed in approximately 30%-75% of all surgical patients suffering from CP[4,5].

The two key issues in the evaluation of focal pancreatic masses in the background of CP are the inability to differentiate between carcinoma and CP mimicking carcinoma, and the impact of this differentiation on subsequent surgical triage and management. The majority of pancreatic tumors (70%) are located in the head of the pancreas and inflammatory masses in CP also seem to prefer the head region[6]. This awareness is widespread in clinical practice but not extensively highlighted in the literature.

In two large series of patients who underwent resection for CP, carcinoma was present in 6 out of 64 cases[7] and 4 out of 250 cases[8] respectively. Similar information is not available from the Indian subcontinent. Furthermore, not much information is available on the outcome of patients who were suspected to have pancreatic carcinoma, but where the pathological diagnosis turned out to be benign.

For patients clinically suspected to harbor malignancy without accompanying definitive documentation of disease, the decision to undergo a major operation may be difficult because of the inherent morbidity and mortality associated with the procedure.

This study aims to prospectively analyse the clinical, biochemical and radiological characteristics of the mass lesions arising in a background of chronic calcific pancreatitis (CCP).

Eighty three patients, who presented with CP and mass lesion in the head of the pancreas between February 2005 and December 2011, were included in the study. Amongst these, 23 patients had ACP and 60 had TCP. ACP was defined as CP associated with the consumption of alcohol greater than 80 gms/d for at least 5 years with history of recurrent acute CP and features of CP on ultrasonogram (USG) or contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen[9]. A diagnosis of TCP was considered in individuals belonging to younger age[2,10], teetotaler with the presence of large intraductal calculi, with or without diabetes and/or steatorrhea.

A detailed history and clinical examination was recorded. The variables analysed from history included details of smoking, family history of CP/pancreatic malignancy, details of abdominal pain (duration/sudden increase), jaundice, significant weight loss, persistent vomiting (due to gastric outlet obstruction), diabetes (recent onset/sudden worsening) and steatorrhea.

The diagnostic workup included liver function tests, serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9), USG of the abdomen and CECT abdomen. In CECT, the following parameters were noted: (1) Head mass: The size and its characteristics, e.g., presence of cystic areas. Head mass was defined as focal enlargement of the head more than 35 mm on USG or CECT scan[11,12]; (2) Calcification-Distribution and type: Alcoholic chronic calcific pancreatitis is characterized by small, speckled, irregular calcification usually in small ducts[13] where as in TCP the calculi are large and dense with discrete margins and most often located in the large ducts that may even reach to a size of up to 4.5 cm in diameter[14,15]; (3) Size of the common bile duct (CBD); and (4) Size of the main pancreatic duct (MPD) in the head, body and tail regions.

Magnetic resonance cholangio pancreatography was performed in selected cases. Only individuals with the typical features of chronic calcific pancreatitis on CECT mentioned above were included in the study. Pre-operative USG/CT guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of the head mass was carried out in selected patients in whom malignancy was highly suspected. These included patients above the age of 55 years[16], elevated and rapidly rising serum bilirubin levels[16,17], elevated serum CA 19-9 levels more than 120 U/mL[18], sudden worsening of abdominal pain[19], significant weight loss[19], and worsening diabetes mellitus[20].

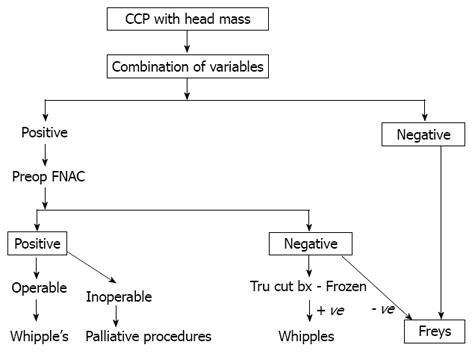

In patients where the FNAC was positive and the lesion operable, Whipple’s procedure[21] was considered. If inoperable, surgical or endoscopic palliative procedures were considered. In patients where FNAC was negative, per-operative trucut biopsy with frozen section from the head mass was carried out. When frozen sections were negative for malignancy, Frey’s procedure[22] with or without choledochoduodenostomy (CDD) was performed and Whipple’s procedure or a bypass was performed if the trucut biopsy was positive for malignancy. Patients without high suspicion of malignancy did not undergo pre-operative FNAC and Frey’s procedure with or without CDD was carried out. The cored pancreatic tissue was sent for histopathological examination. Details of surgery, radiological intervention, complications and the final pathological diagnosis were recorded. All the patients were followed up either in the outpatient department, or by telephone interviews until the end of the study.

Simple descriptive statistics were used. Data were reported as mean ± SD. The Pearson χ2 test and the Fisher exact probability test were used to compare categorical variables. Student t-test was used to compare the mean values of imaging findings (CBD, MPD size) and laboratory data (Serum bilirubin, CA 19-9) between the groups. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC curve) analysis was performed to calculate the cutoff valves of serum bilirubin, CA 19-9, MPD and CBD size. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive valve (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated using these cut off points. Multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression model. P value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using software package, SPSS version 15 for Windows.

Eighty three patients with pancreatic head mass in the setting of CP were enrolled in the study. The study included 56 men (67.5%) and 27 women (32.5%). Sixty patients had TCP (72.3%) and 23 (27.7%) had alcohol related CCP. Histologically, it was confirmed that 55 of the 83 patients had an inflammatory head mass (66.3%) and 28 (33.7%) had a malignant head mass. The mean age of individuals with benign inflammatory mass and those with malignant mass was 38.4 years and 45 years, respectively.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the two groups of patients. Significant clinical features that predicted a malignant head mass in CP were presence of a head mass in CCP of the tropics, age, jaundice, sudden worsening abdominal pain, gastric outlet obstruction and significant weight loss (P≤ 0.05). Gender, smoking, steatorrhoea, and diabetes mellitus (recent/worsening diabetes) did not influence the presence of a malignant head mass in CCP.

| Variables | Benign (n = 55) | Malignant (n = 28) | P value |

| Mean age (yr) | 38.4 | 45 | 0.02 |

| Gender | 0.35 | ||

| Male | 39 (47) | 17 (20.5) | |

| Female | 16 (19.3) | 11 (13.3) | |

| Etiology | 0.05 | ||

| Tropical | 36 (43.4) | 24 (28.9) | |

| Alcoholic | 19 (22.9) | 4 (4.8) | |

| Smoking | 24 (28.9) | 7 (8.4) | 0.14 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Jaundice | 10 (12) | 21 (25.3) | 0.001 |

| Abdominal pain (sudden worsening) | 10 (12) | 23 (27.7) | 0.001 |

| Persistent vomiting (GOO) | 2 (2.4) | 9 (10.8) | 0.001 |

| Significant wt. Loss | 22 (26.5) | 25 (13.1) | 0.001 |

| Steatorrhea | 10 (12) | 5 (6) | 0.97 |

| Diabetes (Recent onset/sudden worsening) | 20 (24.1) | 14 (16.9) | 0.23 |

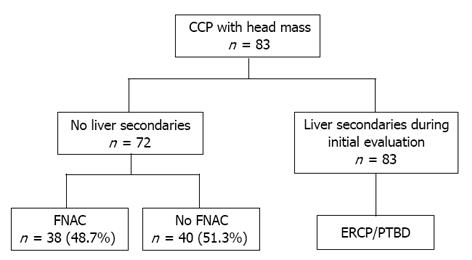

Of the 83 patients studied, 5 were found to have malignant head mass with liver secondaries, malignancy being confirmed by tissue biopsy. Pre-operative USG/CT guided FNAC was performed in 38 (48.7%) of the 78 patients without liver secondaries who were strongly suspected of having malignant head mass (Figure 1).

Malignancy was confirmed by FNAC or tissue biopsy. Out of the 18 patients who underwent intra-operative trucut frozen section biopsy, one was positive for malignancy and Whipple’s procedure was carried out on this patient. Patients with negative intra-operative trucut biopsy underwent Frey’s procedure, with or without CDD. The histopathology of the cored-out tissue was benign in 16 patients and malignant in one patient who died 6 mo later.

Whipple’s procedure was erfprmed on one patient in whom the head mass appeared malignant intraoperatively although the histopathology in this patient was negative for malignancy (Table 2). One patient in this group, who was found to have a malignant head mass with liver secondaries on laparotomy, underwent bypass surgery. All the others in this group had benign mass, confirmed by histopathological examination.

| Sl.no | Procedures | n = 40 |

| 1 | Frey’s procedure | 34 |

| 2 | Frey’s + CDD | 4 |

| 3 | Whipple’s procedure | 1 |

| 4 | Bypass for liver metastasis | 1 |

Comparison of the laboratory parameters and radiological features between these two groups of patients with benign and malignant head mass show that serum bilirubin, CA 19-9, MPD size and CBD size were the factors significantly predicting malignant mass in CP (P≤ 0.05) (Table 3).

| Variables | n | Mean ± SD | t-test | P value |

| Serum Bilirubin (mg%) | 5.7 | < 0.001 | ||

| Benign | 55 | 2.06 ± 2.76 | ||

| Malignant | 28 | 9.58 ± 6.67 | ||

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | 6.2 | < 0.001 | ||

| Benign | 55 | 55.3 ± 126.2 | ||

| Malignant | 28 | 955 ± 751.9 | ||

| MPD Diameter (mm) | 3.5 | 0.001 | ||

| Benign | 55 | 7.7 ± 3.2 | ||

| Malignant | 28 | 12.7 ± 6.9 | ||

| CBD Size (mm) | 4.7 | < 0.001 | ||

| Benign | 55 | 8.7 ± 5.1 | ||

| Malignant | 28 | 15.5 ± 6.6 |

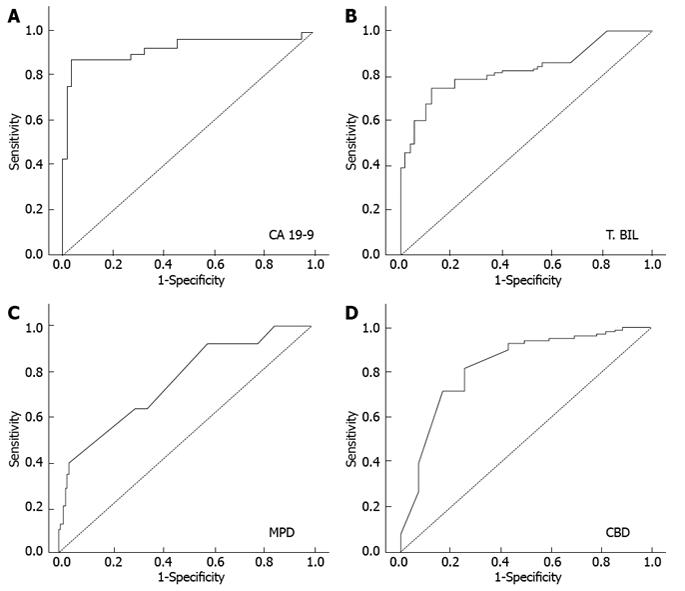

The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis was performed and the cut off value of 5.8 mg/dL for serum bilirubin, 127 U/mL for CA 19-9, 11.5 mm for MPD size and 14.5 mm for CBD size was reached (Figure 2). The sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were calculated using these cut off points and depicted in Table 4.

| Parameters | Cut off value | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

| CA 19-9 | 127 U/mL | 85.7% | 96.5% | 92.3% | 93.2% |

| T.Bilirubin | 5.80 mg% | 67.9% | 89.1% | 75.0% | 83.1% |

| MPD | 11.5 cms | 46.4% | 90.9% | 72.2% | 76.9% |

| CBD | 14.5 cms | 71.4% | 83.6% | 69.0% | 85.2% |

On multivariate analysis, CA 19-9 was the single most significant factor in predicting malignancy in patients with CCP and head mass (Table 5). The sensitivity and specificity were 100% when a combination of serum bilirubin > 5.8 mg/dL, CA 19-9 > 127 U/mL, MPD > 11.5 mm and CBD > 14.5 mm was taken into consideration.

| Variables | β | SE | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(β) |

| Jaundice | -0.768 | 2.112 | 0.132 | 1 | 0.716 | 0.464 |

| Worsening pain | -1.109 | 1.128 | 0.967 | 1 | 0.325 | 0.330 |

| GOO | -1.090 | 1.217 | 0.803 | 1 | 0.370 | 0.336 |

| Wt loss | -1.755 | 1.226 | 2.049 | 1 | 0.152 | 0.173 |

| Cause | -0.980 | 1.173 | 0.698 | 1 | 0.403 | 0.375 |

| Total. Bil | -0.254 | 0.213 | 1.428 | 1 | 0.232 | 0.776 |

| CA19.9 | -0.005 | 0.002 | 4.085 | 1 | 0.043 | 0.995 |

| MPD | -0.128 | 0.148 | 0.756 | 1 | 0.385 | 0.879 |

| CBD | 0.072 | 0.139 | 0.272 | 1 | 0.602 | 1.075 |

| Constant | 5.956 | 2.103 | 8.020 | 1 | 0.005 | 386.147 |

There was no operative mortality. Major post operative complications occurred in 12 patients (15.8%). These included pulmonary complications, wound infection, intra peritoneal abscess, intra abdominal bleed and pancreatic leak. All the complications were managed conservatively. The mean follow up period was in the range of 6-60 mo. Four patients were lost to follow up. Eleven patients died during the follow up period due to advanced malignancy or cardiac causes. Twenty patients required hospitalisation and the details are shown in Table 6.

| Readmission | No. of patients |

| Post Frey’s | 10 |

| Pain | 6 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 3 |

| DKA | 1 |

| Post Whipple’s | 4 |

| Recurrence | 1 |

| Liver secondaries | 2 |

| Others (cardiac) | 1 |

| Post bypass | |

| Celiac ganglion block | 6 |

During the follow up, the one patient who had Whipple’s procedure for benign head mass developed tuberculous cervical lymphadenopathy with severe exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. Three patients died post Whipple’s during the follow up period; two of liver secondaries and one of myocardial infarction (Table 6).

A sub group of patients with CP suffer from an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas[23,24]. These mass lesions present great diagnostic and therapeutic dilemas and malignancy needs to be ruled out with certainty. While a positive biopsy is useful, a negative biopsy does not rule out malignancy. Patients with inflammatory head mass and those with malignancy may present with the similar symptoms of jaundice, gastric outlet obstruction, back ache and weight loss. In both the conditions the patients are lean and emaciated[25].

Diagnosis is difficult even during surgery, because the features of malignant head mass such as presence of a hard mass, presence of vascular invasion, adjacent organ invasion, are also seen in CCP with inflammatory head mass. The definitive evidence of malignancy in these patients is the presence of metastasis or a positive tissue biopsy.

Inflammatory head mass in CP may be operated upon with Beger’s or Frey’s procedures[26], while malignant pancreatic head mass would require a Whipple’s procedure[27]. When the diagnosis is in doubt a radical approach is ideal. Epidemiological studies have shown that the risk of development of ductal pancreatic cancer is increased in a patient with CP[28-33]. Furthermore the risk of pancreatic cancer was independent of the underlying cause of CP[28].

The incidence of malignancy in patients with head mass in the background of CP is 33.7% in our study. The major etiology for malignant mass was TCP (85.7%) and only 14.3% of malignant masses were due to alcoholic pancreatitis. Ramesh et al[10], in a series of 91 patients with TCP, showed that 19 (21%) had associated malignancy. However this study included all patients with tropical pancreatitis, irrespective of the head mass.

Biochemical analysis of patients with CP and inflammatory head mass has shown that 1/3rd of the patients exhibit cholestasis and about 15% have clinical jaundice[34]. The bilirubin level was much higher with malignancy than in CP[16]. Perhaps, more important than the absolute rise of bilirubin was the pattern of elevation. In patients with malignancy, bilirubin increased progressively until the biliary tree was decompressed, while with CP bilirubin rose to a peak and then fell as the attack subsided.

In our study only 10 out of 55 patients with inflammatory head mass (18.2%) presented with jaundice. Among these 10 patients, jaundice subsided in 6 within 3 wk. Seventy five percent of patients with malignant head mass presented with jaundice. The mean serum bilirubin value in our study was 2.06 mg% in inflammatory masses and 9.58 mg% in malignant masses. Frey and coworkers found that serum bilirubin was seldom higher than 10 mg% in CP and usually diminishes in 7-10 d as inflammation subsides[17].

The “duct penetrating sign” seen in 85% of CP and in only 4% of patients with cancer, helps to distinguish an inflammatory from malignant head mass. It refers to a non-obstructed MPD penetrating an inflammatory mass, unlike obstruction caused by pancreatic carcinoma[35]. Hence gross dilatation of MPD occurs proximal to an obstruction in malignancy. In our study dilatation of MPD more than 11.5 mm predicted malignancy with a specificity of 90.9%.

The CBD may be dilated even in CP and studies have shown that CBD dilatation is not specific for malignancy[36]. Our study shows that a CBD diameter of more than 14.5 mm was predictive of malignancy with a sensitivity and specificity of 71.4% and 83.6%, respectively.

Multivariate analyses of risk factors in our study have shown CA 19-9 as the only significant risk factor predicting malignancy in patients with CCP and head mass. CA 19-9 is useful in establishing the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer[18] with a sensitivity of 80%-85% and specificity of 85%-90%[37,38]. However, in patients with obstructive jaundice, serum CA 19-9 may be elevated even in the absence of malignancy although levels seldom exceed 100-120 U/mL[18]. So, caution needs to be exercised in the interpretation of CA 19-9 as a marker for differentiating carcinoma from pancreatitis, especially in patients with biliary obstruction. The CA 19-9 values in our study show a cut off of 127 U/mL to predict malignancy in patients with CP and head mass, with a sensitivity of 85.7% and specificity of 96.5%. In a similar study by Bedi et al[39], which aimed to assess the value of CA 19-9 in patients with CP and a head mass lesion, levels in excess of 300 U/mL suggested malignancy with 100% specificity.

Though pancreaticoduodenectomy has been described as a procedure for patients with CP, most of the evidence comes from the western literature where alcohol is the common etiology. In the Indian scenario, where TCP is very common, pancreaticoduodenectomy is associated with considerable post operative morbidity because these patients are nutritionally depleted with exocrine and endocrine deficiency. So, the need to differentiate benign from malignant is felt more strongly in our part of the world. After analysing this study, we proposed a management algorithm for patients with chronic calcific pancreatitis and head mass (Figure 3).

In conclusion, according to this study, a serum bilirubin more than 5.8 mg/dL, CA 19-9 more than 127 U/mL, MPD more than 11.5 mm and CBD more than 14.5 mm are associated with high sensitivity and specificity for predicting malignancy in patients with chronic calcific pancreatitis and head mass. Multivariate analysis revealed CA 19-9 to be the single most significant factor in predicting malignancy in patients with CCP and head mass.

Pancreatic head mass in chronic pancreatitis (CP) is most often inflammatory and malignancy needs to be ruled out. Differentiating inflammatory from malignant head mass in the background of chronic calcific pancreatitis is difficult and there is a need to establish the correct diagnosis for proper treatment.

There is no investigation which can reliably identify malignancy in a patient with chronic calcific pancreatitis with pancreatic head mass. The surgical procedure is different for the two cases and failure to identify malignancy before surgery is disasterous. The authors aim to identify clinical and biochemical factors which can predict malignancy in chronic calcific pancreatitis with head mass.

This study has not only tried to identify the factors, but has also identified the cutoff values of the significant radiological and biochemical factors to help differentiate malignant from benign. This could be the first step in devising a scoring system to increase the specificity and sensitivity of differentiation.

This study would help in the vital identification of malignancy in a patient with chronic calcific pancreatitis with head mass and thereby in advocating appropriate treatment.

CP, a disease characterized by irreversible destruction and fibrosis of exocrine parenchyma, leads to exocrine insufficiency and progressive endocrine failure, resulting in diabetes. In the tropics there is a distinct form of non alcoholic type of CP called tropical calcific pancreatitis (TCP). The features of TCP include younger age of onset, presence of large intraductal calculi, an accelerated course of disease leading to end points of diabetes or steatorrhea, and a high susceptibility to pancreatic cancer.

The authors have identified the clinical and biochemical factors which can predict malignancy in chronic calcific pancreatitis with pancreatic head mass. They have also defined the cutoff values for those significant factors. This can help predict malignancy in an otherwise difficult to diagnose situation.

P- Reviewer Kluger Y S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Pitchumoni CS. Chronic pancreatitis: a historical and clinical sketch of the pancreas and pancreatitis. Gastroenterologist. 1998;6:24-33. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Mohan V, Premalatha G, Pitchumoni CS. Tropical chronic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:337-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Klöppel G, Maillet B. Chronic pancreatitis: evolution of the disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1991;38:408-412. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Falconi M, Casetti L, Salvia R, Sartori N, Bettini R, Mascetta G, Bassi C, Pederzoli P. Pancreatic head mass, how can we treat it? Chronic pancreatitis: surgical treatment. JOP. 2000;1:154-161. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Beger HG, Schlosser W, Friess HM, Büchler MW. Duodenum-preserving head resection in chronic pancreatitis changes the natural course of the disease: a single-center 26-year experience. Ann Surg. 1999;230:512-519; discussion 512-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pulay I, Tihanyi TF, Flautner L. Pancreatic head mass: what can be done? Classification: the clinical point of view. JOP. 2000;1:85-90. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Moossa AR, Levin B. The diagnosis of “early” pancreatic cancer: the University of Chicago experience. Cancer. 1981;47:1688-1697. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Zografos GN, Bean AG, Bowles M, Williamson RC. Chronic pancreatitis and neoplasia: correlation or coincidence. HPB Surg. 1997;10:235-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sata N, Koizumi M, Nagai H. Alcoholic pancreatopathy: a proposed new diagnostic category representing the preclinical stage of alcoholic pancreatic injury. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42 Suppl 17:131-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ramesh H, Augustine P. Surgery in tropical pancreatitis: analysis of risk factors. Br J Surg. 1992;79:544-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Strate T, Taherpour Z, Bloechle C, Mann O, Bruhn JP, Schneider C, Kuechler T, Yekebas E, Izbicki JR. Long-term follow-up of a randomized trial comparing the beger and frey procedures for patients suffering from chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2005;241:591-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Amudhan A, Balachandar TG, Kannan DG, Rajarathinam G, Vimalraj V, Rajendran S, Ravichandran P, Jeswanth S, Surendran R. Factors affecting outcome after Frey procedure for chronic pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford). 2008;10:477-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lesniak RJ, Hohenwalter MD, Taylor AJ. Spectrum of causes of pancreatic calcifications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:79-86. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Thomas PG, Augustine P, Ramesh H, Rangabashyam N. Observations and surgical management of tropical pancreatitis in Kerala and southern India. World J Surg. 1990;14:32-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barman KK, Premalatha G, Mohan V. Tropical chronic pancreatitis. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:606-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wapnick S, Hadas N, Purow E, Grosberg SJ. Mass in the head of the pancreas in cholestatic jaundice: carcinoma or pancreatitis? Ann Surg. 1979;190:587-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Frey CF, Suzuki M, Isaji S. Treatment of chronic pancreatitis complicated by obstruction of the common bile duct or duodenum. World J Surg. 1990;14:59-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Minghini A, Weireter LJ, Perry RR. Specificity of elevated CA 19-9 levels in chronic pancreatitis. Surgery. 1998;124:103-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Augustine P, Ramesh H. Is tropical pancreatitis premalignant? Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1005-1008. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Saruc M, Pour PM. Diabetes and its relationship to pancreatic carcinoma. Pancreas. 2003;26:381-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Whipple AO, Parsons WB, Mullins CR. Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Ann Surg. 1935;102:763-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 882] [Cited by in RCA: 894] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Frey CF, Smith GJ. Description and rationale of a new operation for chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1987;2:701-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bordalo O, Bapista A, Dreiling D, Noronha M. Early patho morphological pancreatic changes in chronic alcoholism. In: GYR KE, Singer MV, Sarles H. Pancreatitis-concepts and classification, Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam 1982; 642. |

| 24. | Buchler M, Malfertheiner P, Friess H, Senn T, Beger HG. CP with inflammatory mass in the head of pancreas; a special entity? New York: Springer-Verlag 1993; 41-46. |

| 25. | Evans JD, Morton DG, Neoptolemos JP. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:543-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Beger HG, Büchler M, Bittner RR, Oettinger W, Roscher R. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in severe chronic pancreatitis. Early and late results. Ann Surg. 1989;209:273-278. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Traverso LW. The pylorus - preserving whipple procedure for severe complications of CP. Malfertheimer P, editiors. Standards of pancreatic surgery. Heidelberg: Springer verlag 1993; 397. |

| 28. | Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, Ammann RW, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, Dimagno EP, Andrén-Sandberg A, Domellöf L. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Pancreatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1433-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1255] [Cited by in RCA: 1139] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Schlosser W, Schoenberg MH, Rhein E, Siech M, Gansauge F, Beger HG. [Pancreatic carcinoma in chronic pancreatitis with inflammatory tumor of the head of the pancreas]. Z Gastroenterol. 1996;34:3-8. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Bansal P, Sonnenberg A. Pancreatitis is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:247-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ekbom A, McLaughlin JK, Karlsson BM, Nyrén O, Gridley G, Adami HO, Fraumeni JF. Pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:625-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fernandez E, La Vecchia C, Porta M, Negri E, d’Avanzo B, Boyle P. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 1995;11:185-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Medeira I, Pessione F, Malka D, Hammel P, Ruszniewski P, Bernades P. The risk of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in patients with CP: Myth or reality? Gastroenterology. 1998;114: A481. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Schlosser W, Poch B, Beger HG. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection leads to relief of common bile duct stenosis. Am J Surg. 2002;183:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ichikawa T, Sou H, Araki T, Arbab AS, Yoshikawa T, Ishigame K, Haradome H, Hachiya J. Duct-penetrating sign at MRCP: usefulness for differentiating inflammatory pancreatic mass from pancreatic carcinomas. Radiology. 2001;221:107-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Petrozza JA, Dutta SK. The variable appearance of distal common bile duct stenosis in chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:447-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Steinberg W. The clinical utility of the CA 19-9 tumor-associated antigen. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:350-355. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Paganuzzi M, Onetto M, Marroni P, Barone D, Conio M, Aste H, Pugliese V. CA 19-9 and CA 50 in benign and malignant pancreatic and biliary diseases. Cancer. 1988;61:2100-2108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Bedi MM, Gandhi MD, Jacob G, Lekha V, Venugopal A, Ramesh H. CA 19-9 to differentiate benign and malignant masses in chronic pancreatitis: is there any benefit? Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28:24-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |