Published online Aug 27, 2011. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v3.i8.119

Revised: May 26, 2011

Accepted: June 5, 2011

Published online: August 27, 2011

AIM: To simulate a hypothetical increase of 50% in the number of pancreas-kidney (PK) transplantations using less-than-ideal donors by a mathematical model.

METHODS: We projected the size of the waiting list by taking into account the incidence of new patients per year, the number of PK transplantations carried out in the year and the number of patients who died on the waiting list or were removed from the list for other reasons. These variables were treated using a model developed elsewhere.

RESULTS: We found that the waiting list demand will meet the number of PK transplantation by the year 2022.

CONCLUSION: In future years, it is perfectly possible to minimize the waiting list time for pancreas transplantation through expansion of the donor pool using less-than-ideal donors.

- Citation: Chaib E, Jr MAFR, Santos VR, Jr RFM, D’Albuquerque LAC, Massad E. A mathematical model for shortening waiting time in pancreas-kidney transplantation. World J Gastrointest Surg 2011; 3(8): 119-122

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v3/i8/119.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v3.i8.119

São Paulo is a Brazilian state pioneering transplantation surgery. Brazilian law was changed (1999) and pancreas-kidney (PK) transplantation became possible because of state financial support for these procedures. Since then the patient waiting list for PK transplantation has increased and now approximately 154 cases per month are referred to a single list at the central organ procurement organization.

Simultaneous PK transplantation has become the therapy of choice for patients with end-stage renal disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus. Over the past 20 years, PK transplantation outcomes have improved significantly to the point that the majority of recent data demonstrate long-term survival benefits and some protection from progressing secondary complications[1-4].

The gap between the number of transplantable organs from deceased donors and the number of patients awaiting transplantation continues to increase each year. The number of people waiting for PK transplantation in our state is approximately 2.5-fold the number receiving transplantation.

The aim of this study is to assess the performance of our state PK transplantation program and to evaluate when the number of transplantations will meet our waiting list demand.

We collected official data from the State Transplantation Center (Sao Paulo State Secretariat) from our PK transplantation program between January 1999 and December 2007. Only cadaveric PK transplantation was included. The data related to pancreas transplantation in our state includes: simultaneous PK transplantation, pancreas after kidney transplantation and pancreas alone. Table 1. shows the actual number of PK transplantations (Tr), the incidence of new patients on the list (I) and the number of patients who died while on the waiting list (D) in the State of Sao Paulo since 2000. As described previosly[5] we projected the size of the waiting list (L) by taking into account the incidence of new patients per year (I), the number of PK transplantations carried out in the year (Tr) and the number of patients who died on the waiting list or were removed from the list for other reasons (D).

| Yr | I | D | Tr |

| 2000 | 163 | 38 | 33 |

| 2001 | 126 | 51 | 52 |

| 2002 | 128 | 46 | 63 |

| 2003 | 138 | 48 | 74 |

| 2004 | 143 | 52 | 82 |

| 2005 | 169 | 58 | 64 |

| 2006 | 213 | 69 | 72 |

| 2007 | 167 | 71 | 85 |

We took the data of Tr from Table 1 and fitted a continuous curve by the method of maximum probability[6], in order to project the number of future transplantations, Tr. Then we projected the size of the waiting list, L, by taking into account the incidence of new patients per year, I, the number of transplantation carried out in that year, Tr, and the number of patients who died on the waiting list, D. In other words, the list size at time t+1 is equal to the size of the list at the time t, plus the new patients coming onto the list at time t, minus those patients who have died on the waiting list at time t, minus those patients who have received a graft at time t. The variables I, and D, from 2007 onward were projected by fitting an equation by maximum probability, in the same way that we did for Tr. The dynamics of the waiting list is given by the equation: Lt+1 = Lt + It - Dt + Trt.

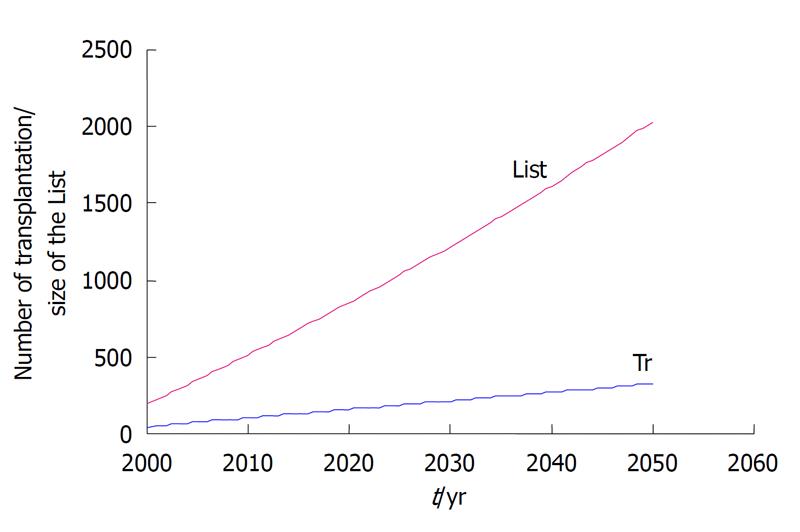

The results can be seen in Figure 1. Note that, since 2000, both the number of transplantations (blue line) and the size of the waiting list (red line) have increased in a linear manner, and will not meet each other in the future. In other words, the list size is growing much faster than the number of PK transplantations performed in our state.

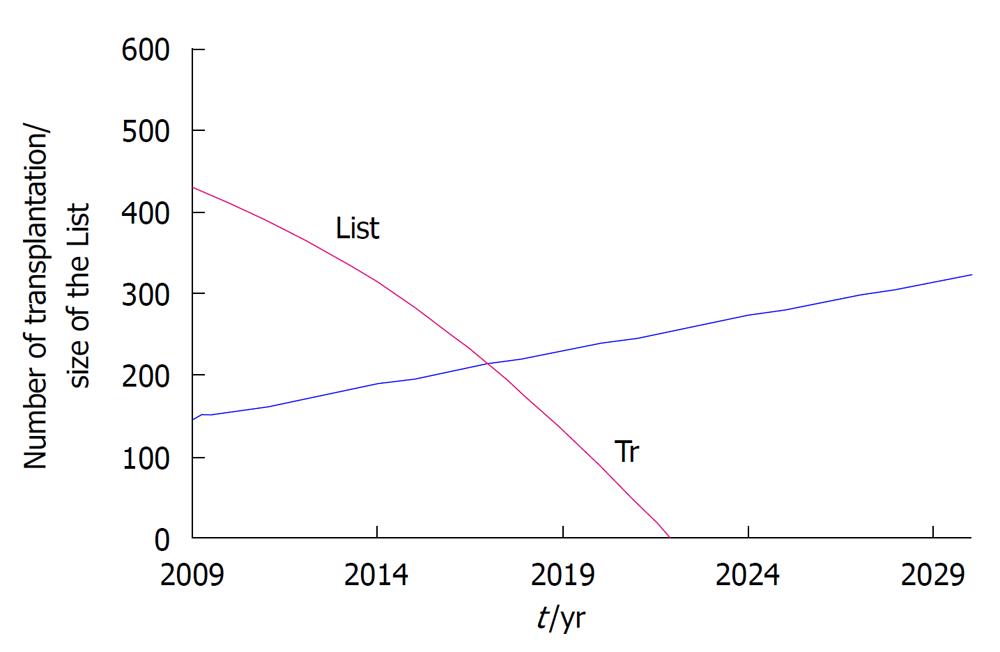

We then simulated a hypothetical 50% increase in the number of PK transplantations performed in order to check when the two curves would meet each other. The results can be seen in Figure 2.

Note that by increasing the annual number of transplantation by 50%, the waiting list will come to an end in 2022.

Currently, solid-organ pancreas transplantation is the only treatment of type 1 diabetes that can restore complete insulin independence and normal blood glucose levels. The aim of a successful pancreas transplantation was not only to provide normoglycemia but also to slow down the development or progression of diabetes-related complications[7]. Results of pancreas transplantation have improved significantly over the last 25 years. There are multiple reasons for this including superior immunosuppression, better post-transplant management, and modern surgical techniques[2,3].

In our state, current organ donation of the 7.09 per million inhabitants has not reached its full potential[8]. This fact alone is responsible for the huge demand pressure on our organ waiting list. One way to ease this pressure is to increase organ donation at least two-fold; in other words we should have been doing 15 organ retrievals per million inhabitants.

The number of PK transplantations in our state increased, approximately, 2.7-fold (33 to 85) from 2000 to 2007. On the other hand, the number of patients on the PK waiting list jumped to 2.98-fold (163 to 385) from 2000 to 2007. The gap between the number of PK transplantations and patients on the waiting list is widening fast, leading to an anticipated increase in the number of deaths.

While we have improved our performance in PK transplantation from the year 2000 to 2007, 1.8 PK transplantation/million inhabitants and 4.72 PK transplantation/million inhabitants respectively, this was not sufficient to meet our state demand for PK transplantation. During the study time frame, approximately, 3 pancreata/million inhabitants were discarded. Thus attempts to maximize pancreas utilization to satisfy the demand is a problem of increasing significance.

Another approach to expanding the donor pool for pancreas transplantation is to use pancreata from donation after cardiac death (DCD). While the use of kidneys and livers from DCD donors is increasing[9,10], the use of DCD pancreata is still low (UNOS). DCD is not a novel concept. Prior to the institution of brain death laws in the United States, all donors were DCD donors. Pancreas procurement from DCD donors was described for the first time in 1968[11]. However, routine implementation of DCD recovery at many centers has been impeded by ethical concerns, logistical considerations, and fear of poor functional outcomes. Limited experience with DCD pancreas transplantation is available, and this is primarily short term follow-up in a small number of patients[12,13]. In comparison to a contemporaneous cohort of recipients of conventional heart-beating donors organs, SPK transplantation from selected DCD donors resulted in similar excellent patient, kidney, and pancreas graft survival[14].

The lengthening waiting lists caused by the shortage of available organs and the increasing number of patients with end-stage organ disease have led to predictable rise in deaths; therefore the search for new sources of transplantable organs is imperative[15,16]. It has been suggested that, with the current standard of practice, the pancreas is the least likely abdominal organ to be deemed suitable for transplantation[17]. Waiting list time for simultaneous PK transplantation is increasing. In the United States of America at the end of 1993, there were 855 patients awaiting simultaneous PK transplantation, whereas at the end of 2002 there were 2425 (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, OPTN, USA).

Since pancreas is a limited national resource our proposal is: (1) Improve the organ donation campaign; (2) Concentrate funding resources in public university hospitals in order to improve PK performance; and (3) Expand the donor pool using less-than-ideal donors such as: DCD[12-14], living donors[18-20] and pediatric donors[21].

In this study, we simulated a hypothetical increase of 50% in the number of PK transplantations and we found that the waiting list demand will meet the number of PK transplantations by the year 2022 (Figure 2). This means that is perfectly possible in the years ahead to minimize the waiting time for pancreas transplantation if we expand the donor pool using less-than-ideal donors.

In conclusion, the implementation of the measures mentioned above would immediately ease the pressure on our waiting list for PK transplantation and this, coupled with the potential future 50 % increase in the number of PK transplantations, should minimize transplant patient waiting time.

Simultaneous pancreas-kidney (PK) transplantation has become the therapy of choice for patients with end-stage renal disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus. Over the past 20 years, PK transplantation outcomes have improved significantly to the point where the majority of recent data demonstrate long-term survival benefits and some protection from progressing secondary complications.

Since pancreas is a limited national resource, our proposal is: (1) improve the organ donation campaign; (2) concentrate funding resources in public university hospitals in order to improve PK performance; and (3) expand the donor pool using less-than-ideal donors such as: donation after cardiac death, living donors and pediatric donors.

The authors projected the size of the waiting list (L) by taking into account the incidence of new patients per year (I), the number of PK transplantations carried out in the year (Tr) and the number of patients who died on the waiting list or were removed from the list for other reasons (D).

In this study the authors simulated a hypothetical increase of 50% in the number of PK transplantations and we have found that the waiting list demand will meet the number of PK transplantation by the year 2022. This means that is perfectly possible in the years ahead to minimize the waiting time for pancreas transplantation by expanding the donor pool using less-than-ideal donors.

It is an interesting work and thus could be published.

Peer reviewer: Theodoros E Pavlidis, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Surgery, University of Thessaloniki, Hippocration Hospital, A Samothraki 23, Thessaloniki 54248, Greece

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Humar A, Ramcharan T, Kandaswamy R, Gruessner RW, Gruessner AC, Sutherland DE. Technical failures after pancreas transplants: why grafts fail and the risk factors--a multivariate analysis. Transplantation. 2004;78:1188-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Humar A, Kandaswamy R, Granger D, Gruessner RW, Gruessner AC, Sutherland DE. Decreased surgical risks of pancreas transplantation in the modern era. Ann Surg. 2000;231:269-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stratta RJ, Lo A, Shokouh-Amiri MH, Egidi MF, Gaber LW, Gaber AO. Improving results in solitary pancreas transplantation with portal-enteric drainage, thymoglobin induction, and tacrolimus/mycophenolate mofetil-based immunosuppression. Transpl Int. 2003;16:154-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ablorsu E, Ghazanfar A, Mehra S, Campbell B, Riad H, Pararajasingam R, Parrott N, Picton M, Augustine T, Tavakoli A. Outcome of pancreas transplantation in recipients older than 50 years: a single-centre experience. Transplantation. 2008;86:1511-1514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chaib E, Massad E. Liver transplantation: waiting list dynamics in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:4329-4330. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hoel PG. Introduction to Mathematical Statistics. 5th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons 1984; . |

| 7. | Krolewski AS, Warram JH. Epidemiology of late complications of diabetes: A basis for the development and evaluation of preventive programs. Joslin's diabetes mellitis. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins 2005; 795-806. |

| 8. | Garcia VD. Increase number of brazilian transplantations. Have we got anything to celebrate? J Reg C Med S Paulo. 2005;30:1. |

| 9. | Chaib E. Non heart-beating donors in England. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2008;63:121-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chaib E, Massad E. The potential impact of using donations after cardiac death on the liver transplantation program and waiting list in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1732-1736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Calne RY, Williams R. Liver transplantation in man. I. Observations on technique and organization in five cases. Br Med J. 1968;4:535-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | D'Alessandro AM, Odorico JS, Knechtle SJ, Becker YT, Hoffmann RM, Kalayoglu M, Sollinger HW. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney (SPK) transplantation from controlled non-heart-beating donors (NHBDs). Cell Transplant. 2000;9:889-893. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Tojimbara T, Teraoka S, Babazono T, Sato S, Nakamura M, Hoshino T, Nakagawa Y, Fujita S, Fuchinoue S, Nakajima I. Long-term outcome after combined pancreas and kidney transplantation from non-heart-beating cadaver donors. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:3793-3794. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Fernandez LA, Di Carlo A, Odorico JS, Leverson GE, Shames BD, Becker YT, Chin LT, Pirsch JD, Knechtle SJ, Foley DP. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation from donation after cardiac death: successful long-term outcomes. Ann Surg. 2005;242:716-723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chaib E, Massad E. Expected number of deaths in the liver transplantation waiting list in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Transpl Int. 2008;21:290-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chaib E, Massad E. Comparing the dynamics of kidney and liver transplantation waiting list in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Transplantation. 2007;84:1209-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Krieger NR, Odorico JS, Heisey DM, D'Alessandro AM, Knechtle SJ, Pirsch JD, Sollinger HW. Underutilization of pancreas donors. Transplantation. 2003;75:1271-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gruessner RW, Sutherland DE, Drangstveit MB, Bland BJ, Gruessner AC. Pancreas transplants from living donors: short- and long-term outcome. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:819-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sutherland DE, Najarian JS, Gruessner R. Living versus cadaver donor pancreas transplants. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:2264-2266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zieliński A, Nazarewski S, Bogetti D, Sileri P, Testa G, Sankary H, Benedetti E. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant from living related donor: a single-center experience. Transplantation. 2003;76:547-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Van der Werf WJ, Odorico J, D'Alessandro AM, Knechtle S, Becker Y, Collins B, Pirsch J, Hoffman R, Sollinger HW. Utilization of pediatric donors for pancreas transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:610-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |