Published online Aug 27, 2010. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v2.i8.260

Revised: July 18, 2010

Accepted: July 26, 2010

Published online: August 27, 2010

AIM: To prevent pancreatic leakage after pancreaticojejunostomy, we designed a new standardized technique that we term the “Pair-Watch suturing technique”.

METHODS: Before anastomosis, we imagine the faces of a pair of watches on the jejunal hole and pancreatic duct. The first stitch was put between 9 o’clock of the pancreatic side and 3 o’clock of the jejunal side, and a total of 7 stitches were put on the posterior wall, followed by the 5 stitches on the anterior wall. Using this technique, twelve stitches can be sutured on the first layer anastomosis regardless of the caliber of the pancreatic duct. In all cases the amylase activity of the drain were measured. A postoperative pancreatic fistula was diagnosed using postoperative pancreatic fistula grading.

RESULTS: From March 2007 to July 2008, 29 consecutive cases underwent pancreaticojejunostomy using this technique. Pathologic examination results showed pancreatic carcinoma (n = 14), intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm (n = 10), intraductal papillary-mucinous carcinoma (n = 1), carcinoma of ampulla of Vater (n=1), carcinoma of extrahepatic bile duct (n = 1), metastasis of renal cell carcinoma (n = 1), and duodenal carcinoma (n = 1). Pancreaticojejunal anastomoses using this technique were all watertight during the surgical procedure. The mean diameter of main pancreatic duct was 3.4 mm (range 2-7 mm). Three patients were recognized as having an amylase level greater than 3 times the serum amylase level, but all of them were diagnosed as grade A postoperative pancreatic fistula grading and required no treatment. None of the cases developed complications such as hemorrhage, abdominal abscess, and pulmonary infection. There was no postoperative mortality.

CONCLUSION: Our technique is less complicated than other methods and very secure, providing reliable anastomosis for any size of pancreatic duct.

- Citation: Azumi Y, Isaji S, Kato H, Nobuoka Y, Kuriyama N, Kishiwada M, Hamada T, Mizuno S, Usui M, Sakurai H, Tabata M. A standardized technique for safe pancreaticojejunostomy: Pair-Watch suturing technique. World J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 2(8): 260-264

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v2/i8/260.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v2.i8.260

Pancreaticoduodenectomy has become a standard procedure, and the critical step is no longer the resection itself but the reconstruction of the pancreaticoenteric anastomosis. This is underscored by the fact that, despite significantly reduced mortality in recent years, morbidity remains as high as 30% to 50%, even in large series[1]. Complications related to pancreaticoenteric anastomosis are pancreatic fistula, anastomotic dehiscence, abscess formation, and septic hemorrhage. The pancreatic anastomosis is still the Achilles heel of pancreatic surgery because it has the highest rate of surgical complications among all abdominal anastomoses. Many risk factors previously shown to predispose to pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy include advanced age, prolonged operation time, major blood loss, jaundice, soft pancreatic parenchyma, small pancreatic duct, and number of patients per surgeon[2,3].

More than 80 different methods of pancreaticoenteric reconstruction have been proposed, illustrating the complexity of surgical techniques as well as the absence of a gold standard. Pancreatic anastomosis using a jejunal loop is the most commonly used method of surgical reconstruction after pancreatic head resection. There are two main types of anastomosis: pancreatojejunostomy, so-called invagination anastomosis, and pancreaticojejunostomy, so-called duct-to-mucosa anastomosis. It has been found that duct-to-mucosa anastomosis is more effective than invagination anastomosis for the prevention of postoperative pancreatic duct dilatation and atrophy of the remnant pancreas[4,5]. However, prospective randomized trials have found no differences between the two methods regarding fistula rates, morbidity, or mortality[2,6]. Irrespective of the method adopted, it is the technique of anastomosis that is more important than other factors that are known to influence the formation of pancreatic fistulae. It should be therefore emphasized that a standardized approach to pancreatic anastomosis and the consistent practice of a single technique can help to reduce the incidence of complications[7]. For effective prevention of the development of pancreatic leakage, we designed a new standardized technique that we term the “Pair-Watch suturing technique”, which is a duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy technique.

Here we describe our technique of end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy in a typical case in which the caliber of the main pancreatic duct is around 3 mm with normal and soft pancreatic parenchyma. After proximal or medial pancreatectomy, the cut end of the distal pancreas is mobilized for approximately 2 cm to allow the placement of interrupted sutures to the posterior surface of the pancreas. Stay sutures at the superior and inferior border of the cut remnant allow partial reflection of the gland and easier access to the posterior surface. Our procedure consists of two-layer anastomosis; duct-to-mucosa anastomosis and pancreatic parenchymal to jejunal seromuscular anastomosis. We always use a surgical scope with magnification of 1.5 to 2.5, which is very helpful for performing a safe and secure anastomosis.

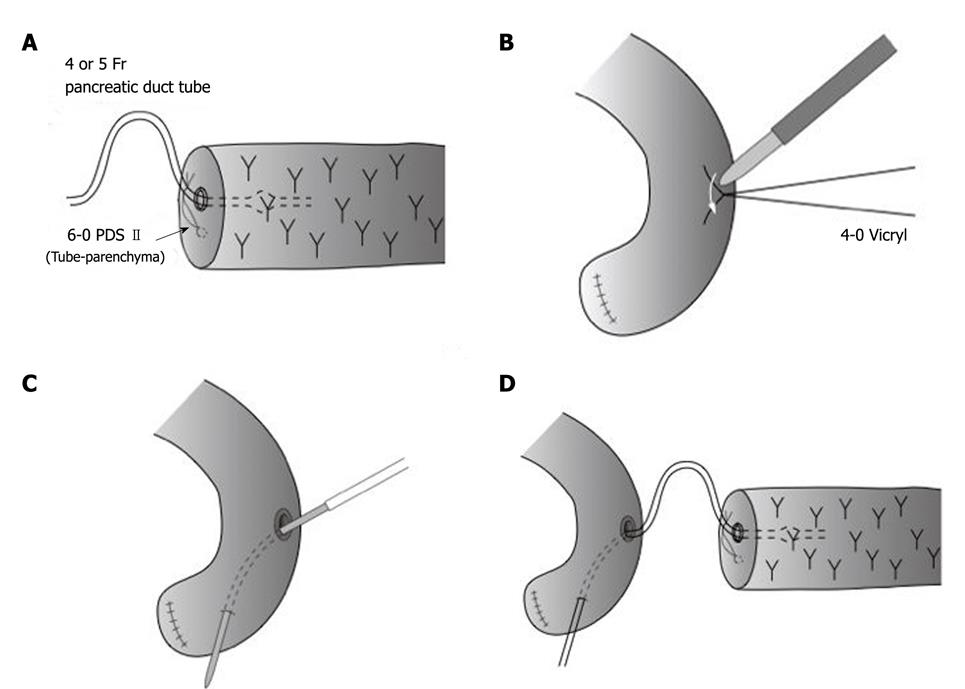

A pancreatic duct tube (4/6 or 5 Fr, Sumitomo Bakelite, Tokyo, Japan) is inserted as a splint tube into the main pancreatic duct of the pancreatic remnant from the cut-end and tied to pancreatic parenchyma with 6-0 PDSII (Ethicon, Inc, Somerville, NJ), as shown in the Figure 1A.

After cutting a very small part (usually 2-3 mm in diameter) of the jejunal serosa using an electric cautery as shown in the Figure 1B, the metallic needle of the pancreatic duct tube is introduced into the jejunum through the site of the serosal cut and then taken out of the distal end of the jejunum (Figure 1C). While interring the stitches on the posterior wall duct-to-mucosa anastomosis of pancreaticojejunostomy, the distance between the induced jejunal hole and the cut end of the main pancreatic duct should be kept at 5 cm or more, making the tube loop-shaped (Figure 1D).

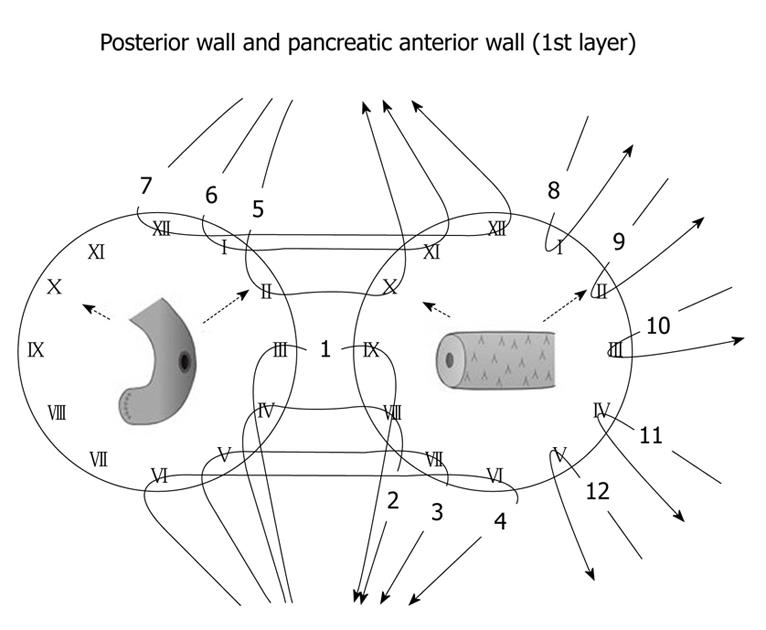

Before starting the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis, we imagine the faces of a pair of watches, the jejunal hole corresponding to the left-side watch and the pancreatic duct hole to the right-side one (Figure 2). The posterior wall of pancreatic duct consists of the latter half of the clock cycle, from 6 o’clock to 12 o’clock, and the posterior wall of jejunal hole consists of the first half of the clock cycle, from 12 o’clock to 6 o’clock.

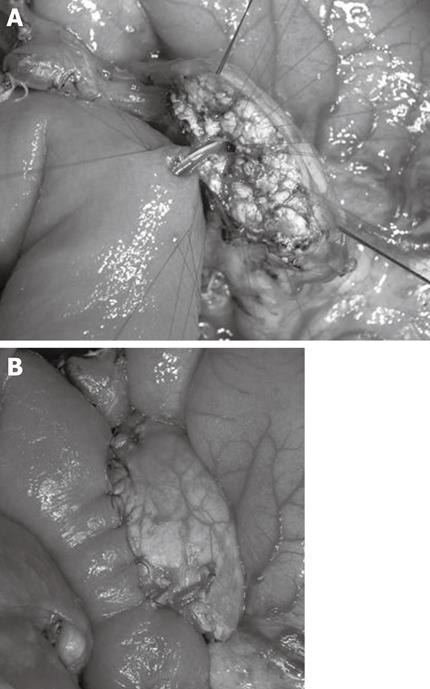

Using a 6-0 PDS II, the first stitch is put in the center of posterior wall, that is, between 9 o’clock of the pancreatic side and 3 o’clock of the jejunal side. The stitch should be made so that a suture knot is placed outside the anastomosis, and the pancreatic duct stitch should be placed at the pancreatic parenchyma from the edge of the duct. The second stitch is put on the caudal side of the first stitch, that is, between 8 o’clock of the pancreatic side and 4 o’clock of the jejunal side. In the same way, the third and fourth stitches are put between 7 o’clock and 5 o’clock, and between 6 o’clock and 6 o’clock, respectively. In the cranial side of the posterior wall anastomosis, the fifth, sixth, and seventh stitches are sequentially put between 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock, between 11 o’clock and 1 o’clock, and between 12 o’clock and 12 o’clock, respectively. After these seven sutures on the posterior wall have been completed, we usually put the remaining 5 stitches from 1 to 5 o’clock on the anterior wall of the pancreatic duct in advance (Figure 2, and 3A). To prevent these twelve sutures from being mixed up, we grasp them with twelve mosquito clamps that are numbered from one to twelve, corresponding to the site from one to twelve o’clock of the pancreatic duct side watch (right side watch) (Figure 2). The jejunum is carefully approximated to the pancreas with simultaneous pulling of the stent tube to make it straight, and the seven knots on the posterior wall are gently tied in order, from the first to seventh stitch.

Thereafter we move to the anterior wall anastomosis. The pancreatic side has been already sutured, and thus the sutured strings are used. Each stitch from 1 to 5 o’clock is placed on the corresponding site on the jejunum from 11 to 7 o’clock. The duct-to-mucosa anastomosis is complete once these 5 stitches have been gently tied. The stent tube is then fixed to the jejunal wall with Witzel’s method using 4-0 Vicryl (Ethicon, Inc, Somerville, NJ) interrupted sutures.

The second layer anastomosis is a pancreatic parenchymal-jejunal seromuscular anastomosis by interrupted sutures with 4-0 Vicryl. Usually, 5-7 stitches each are sutured on the anterior and posterior side (Figure 3B). After completion of the reconstruction, a closed vacuum-drainage system (J-VAC drainage system; Ethicon, Inc, Somerville, NJ) is placed near the site of pancreaticojejunostomy, and the postoperative secretion is routinely monitored with respect to the volume and amylase activity.

In all cases the amylase activity of abdominal drain and serum amylase activity are measured on postoperative day 3. A postoperative pancreatic fistula was diagnosed using the report by Bassi et al[8].

From March 2007 to July 2008, 29 consecutive cases underwent pancreaticojejunostomy using this technique. Pathologic examination results showed pancreatic carcinoma (n = 14), intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm (n = 10), intraductal papillary-mucinous carcinoma (n=1), carcinoma of ampulla of Vater (n = 1), carcinoma of extrahepatic bile duct (n = 1), metastasis of renal cell carcinoma (n = 1), and duodenal carcinoma (n = 1). Pancreaticojejunal anastomoses using this technique were all watertight during the surgical procedure. The mean diameter of main pancreatic duct was 3.4 mm (range 2-7 mm). Three patients were identified as having an amylase level greater than 3 times the serum amylase level, but all of them were diagnosed as grade A postoperative pancreatic fistula grading[8] and required no treatment. None of the cases developed complications such as hemorrhage, abdominal abscess, and pulmonary infection.

The splint tube was usually removed 6 wk after operation, because the stent tube was fixed to the jejunal wall with Witzel’s method using 4-0 Vicryl interrupted sutures. In all patients, the stent tube had been active in draining pancreatic juice of 50-200 mL/d for 7 to 14 d. Thereafter in half of patients we clamped the stent tube as it had become inactive in draining pancreatic. There was no postoperative mortality. All of the patients recovered well in the 8- to 26-mo follow-up period at the time of writing.

Mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy has decreased in recent years. However, it has been shown that pancreatic leakage is still the most important determinant of morbidity, carrying a mortality of 28%[9]. Several methods have been advocated to prevent pancreatic leakage, but a standardized method has not been established. Several steps, such as duct-to-mucosa adaptation and temporary ductal stenting, are thought to be important factors in achieving safe pancreaticojejunostomy. The anastomotic technique, pancreatic duct size, and texture of the remnant pancreas are all identified as significant intraoperative parameters affecting pancreaticojejunostomy leakage and related mortality[9]. Where the pancreas is relatively soft and/or the duct is relatively narrow, the possibility of pancreatic leak is increased[10,11].

We have developed a watertight and standardized pancreaticojejunostomy technique, the pair-watch suturing technique, that is not influenced by the caliber of pancreatic duct. Before introduction of this technique in our institution, the number of stitches used for duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy had been 5 to 7 if the diameter of pancreatic duct is less than 5 mm. In our pair-watch suturing technique, however, the number of stitches is not influenced by the diameter of the duct. This is the most important point of this technique. Twelve stitches on duct-to-mucosa anastomosis are always inserted using a surgical scope, even if the pancreatic duct is 2 mm. By imagining the pancreatic duct and jejunal hole as the faces of a pair of watches, surgeons who are experienced in pancreaticoduodenectomy are able to be aware of every stitch during the procedure and to suture twelve stitches exactly by using the surgical scope. In other words, the technical variations between experienced surgeons can be eliminated by introduction of this technique, resulting in standardization of duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy. Pancreaticodudenectomy is a high-risk, technically demanding operation and the morbidity remains high, even in high-volume centers. Therefore, the adoption of our technique of pancreaticojejunostomy should under the guidance of highly experienced surgeons when less-experienced surgeons are operating.

Many surgeons usually increase the number of stitches when the caliber of pancreatic duct becomes wider. In contrast, they are obliged to decrease the number of stitches, when the duct is narrower. With the narrowing of duct size, the risk of pancreatic fistula significantly increases. Although there is no strong evidence that the functioning of duct-to-mucosa anastomosis depends on the absolute number of stitches used, we believe that increasing the number of stitches for narrow pancreatic ducts makes the anastomosis watertight, resulting in the risk of pancreatic fistula, because a pancreas with a narrow pancreatic duct usually also has soft parenchyma.

In our technique, we always insert the pancreatic duct tube during anastomosis. The insertion of a pancreatic tube has two purposes: one is partial pancreatic juice drainage, and the other is as a probe for secure suturing of the pancreatic duct. For partial drainage, the caliber size of stent tube should be small enough relative to that of the pancreatic duct. If the stent tube is as wide as the pancreatic duct for complete pancreatic juice drainage, the pancreatic duct pressure increases if there is accidental obstruction of the tube, resulting pancreatic leakage. For the anastomosis probe function, putting the stent tube into the site of a duct-to-mucosa anastomosis helps the surgeon make a secure suture because the tube becomes a landmark for the orifice of the anastomosis and prevents accidental suturing of both anterior and posterior walls.

Our technique is not totally original and is similar to the method reported by Z’graggen et al[12]. Their technique used 4-8 sutures for anastomosis, depending on duct size, and they did not use the pancreatic duct tube during duct-to-mucosa anastomosis, resulting in very low pancreatic fistula rate of 2%. In contrast, to standardize the technique we use 12 stitches irrespective of the anatomical characteristics of the pancreatic stump and we keep the stent tube for partial drainage. Given the excellent results of reported by Z’graggen et al[12], it may be thought that we don’t need stent tube insertion because we use twelve stitches even in narrow ducts. To evaluate the necessity of stent tube insertion, now we are now run a prospective study to determine whether the stent tube insertion or the suture technique which is the most significant factor for success.

In conclusion, the results obtained with the described technique of pancreaticojejunostomy indicate that pair-watch suturing technique is less complicated than other methods and very secure, providing reliable anastomosis for any size of pancreatic duct. Although the number of enrolled patients is small, our results are very encouraging and we hope that this method will be used more widely in the future.

The pancreatic anastomosis is still the Achilles heel of pancreatic surgery because it has the highest rate of surgical complications among all abdominal anastomosis.

More than 80 different methods of pancreaticoenteric reconstruction have been proposed, illustrating the complexity of surgical technique as well as the absence of a gold standard. It should be therefore emphasized that a standardized approach to pancreatic anastomosis and the consistent practice of a single technique can help to reduce the incidence of complications.

Many surgeons usually increase the number of stitches when the caliber of pancreatic duct becomes wider. In contrast, they are obliged to decrease the number of stitches, when the duct size becomes narrow. As the duct size narrows, the risk of pancreatic fistula significantly increases. The authors have developed a watertight and standardized pancreaticojejunostomy technique, the Pair-Watch suturing technique, that makes us possible to put 12 stitches even if the duct size is 2 mm.

Since pancreaticodudenectomy is a high-risk, technically demanding operation and the morbidity is still high, even in high-volume centers, this technique of pancreaticojejunostomy should be adopted under the guidance of highly experienced surgeons when less-experienced surgeons are operating.

The Pair-Watch suturing technique for pancreaticojejunostomy is described as the following procedure. Before starting the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis, we imagine the faces of a pair of watches, corresponding the jejunal hole for the left-side watch and the pancreatic duct hole for the right-side one. The posterior wall of the pancreatic duct consists of the latter half of the clock cycle, from 6 o’clock to 12 o’clock, and the posterior wall of jejunal hole consists of the first half of the clock cycle, from 12 o’clock to 6 o’clock.

This paper reports a personal technique of pancreaticoenteric reconstruction developed by the authors. The argument is of great interest and deals with the most controversial topic in pancreatic surgery. The technique is clearly described; the figures add useful details and make the procedure easy to understand.

Peer reviewer: Alessandro Zerbi, MD, Department of Surgery, San Raffaele Hospital, Via Olgettina 60, Milano 20132, Italy

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Yang C

| 1. | Kleespies A, Albertsmeier M, Obeidat F, Seeliger H, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ. The challenge of pancreatic anastomosis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:459-471. |

| 2. | Bassi C, Falconi M, Molinari E, Mantovani W, Butturini G, Gumbs AA, Salvia R, Pederzoli P. Duct-to-mucosa versus end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a prospective randomized trial. Surgery. 2003;134:766-771. |

| 3. | Poon RT, Lo SH, Fong D, Fan ST, Wong J. Prevention of pancreatic anastomotic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;183:42-52. |

| 4. | Hosotani R, Doi R, Imamura M. Duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy reduces the risk of pancreatic leakage after pancreatoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2002;26:99-104. |

| 5. | Tani M, Onishi H, Kinoshita H, Kawai M, Ueno M, Hama T, Uchiyama K, Yamaue H. The evaluation of duct-to-mucosal pancreaticojejunostomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2005;29:76-79. |

| 6. | Grobmyer SR, Pieracci FM, Allen PJ, Brennan MF, Jaques DP. Defining morbidity after pancreaticoduodenectomy: use of a prospective complication grading system. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:356-364. |

| 7. | Shrikhande SV, Barreto G, Shukla PJ. Pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: the impact of a standardized technique of pancreaticojejunostomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:87-91. |

| 8. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. |

| 9. | Yamaguchi K, Tanaka M, Chijiiwa K, Nagakawa T, Imamura M, Takada T. Early and late complications of pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy in Japan 1998. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:303-311. |

| 10. | van Berge Henegouwen MI, De Wit LT, Van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Incidence, risk factors, and treatment of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: drainage versus resection of the pancreatic remnant. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:18-24. |

| 11. | Abete M, Ronchetti V, Casano A, Pescio G. [Pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and treatment]. Minerva Chir. 2005;60:99-110. |

| 12. | Z'graggen K, Uhl W, Friess H, Büchler MW. How to do a safe pancreatic anastomosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:733-737. |