Published online Dec 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i12.3890

Revised: September 15, 2024

Accepted: October 18, 2024

Published online: December 27, 2024

Processing time: 119 Days and 19.8 Hours

The debate regarding the two possible roles of lymphadenectomy in surgical oncology, prognostic or therapeutic, is still ongoing. Furthermore, the use of lymphadenectomy as a proxy for the quality of the surgical procedure is another feature of discussion. Nevertheless, this reckoning depends on patient conditions, aggressiveness of the tumor, the surgeon, and the pathologist, and then it is not an absolute surrogate for the surgical quality. The international guidelines recom

Core Tip: The lymph node yield (LNY) cannot be considered a significant reliable factor in assessing the quality of surgical resection. The aim of the surgeon includes obtaining an intact specimen, and the role of the pathologist includes collecting a high LNY for microscopic examination and reporting the accurate tumor node metastasis (TNM). The involvement of the lymph nodes and the final T and N of TNM can only be known after removing the specimen. Features considering the association with LNY and survival remain issues beyond this step, therefore diligent search for lymph nodes is required on gross examination of the surgical specimen.

- Citation: Morera-Ocon FJ, Navarro-Campoy C, Cardona-Henao JD, Landete-Molina F. Colorectal cancer lymph node dissection and disease survival. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(12): 3890-3894

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i12/3890.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i12.3890

Lymphadenectomy is a mandatory component in oncological resection for solid tumors. The lymph node yield (LNY)

In this editorial we will look at the roles of lymphadenectomy in colorectal cancer (CRC), and discuss the results of studies regarding lymph node harvesting.

This is a core question which may have several answers depending on the type of cancer. At the beginning of the modern era in breast cancer treatment, with Halsted[1], oncologic systemic treatment did not exist and radical surgery with lymphadenectomy was the only way to reduce local recurrence and obtain better survival.

Total mesorectal excision (TME) was popularized and described by Bill Heal in 1982 for surgical management of rectal cancer. TME entails sharp and not blunt dissection of the visceral and parietal layers of the endopelvic fascia, resulting in intact removal of the rectum and mesorectum. Sharp dissection in this avascular plane was demonstrated to decrease local recurrence before the era of neoadjuvant radiotherapy[2,3]. The finding of residual mesorectal fat identified on cross-sectional imaging in more than half of local recurrences in Sweden also suggested that incomplete mesorectal excision was the principal cause of local recurrence[4]. This data also corroborates lymphadenectomy as a therapeutic tool in cancer surgery.

Sigurdson[5] proposed the general oncological idea that the regional control of metastases associated with malignancy could be reached either by lymphadenectomy or by a combination of resection with radiation. Currently, the standard of care for locally advanced rectal cancer (i.e., cT3-4 with or without lymph nodes) is neoadjuvant treatment with radiochemotherapy associated with a meticulous surgical technique[6].

However, in pancreatic adenocarcinoma the role of lymphadenectomy is solely prognostic, and has not been found to correlate with survival or local recurrence[7,8].

The relationship between the improved quality of lymph node assessment and better survival may not be due to a lymphadenectomy therapeutic effect. Rather, the mechanism for this association might be an upstaging phenomenon: When a screening test or other appropriate diagnostic procedure leads to the detection of a disease before it had been detected by the existent previous diagnostic tools, it would allow those patients to migrate from lower tumor node metastasis (TNM) stages into higher TNM stages. The migration would improve survival in the lower stages, and improve survival in the higher stages. Feinstein et al[9] proposed that the taxonomic and statistical consequences of stage migration was called the Will Rogers phenomenon, named after the joke made by this actor, who said “When the Okies left Oklahoma and moved to California, they raised the average intelligence level in both states”.

The pathological staging of CRC is essential for determining prognosis and therapy. The AJCC-UICC TNM staging system (8th edition, 2017) classified N status in N1 when there is spread into 1-3 nearby lymph nodes, and N2 when 4 or more of the regional lymph nodes are involved[10]. It has been shown that 12 to 15 negative lymph nodes predict regional node negativity, and if fewer than 12 nodes are found, additional visual enhancement techniques should be considered[11]. Lymph node involvement is an indicator for adjuvant therapy to reduce the risk of metastasis[12]. Consequently, an insufficient number of histologically studied lymph nodes may downstage the patient neoplasm and mislead the decision for adjuvant treatment.

He et al[13] studied the association between the LNY and overall survival (OS) in patients with stage I and II CRC undergoing radical resection. Their results showed no influence of LNY on survival of patients with stages I and II CRC. They affirm that “the collection of all lymph nodes in the specimen is an impractical approach”. They also declare that “they did not find that the total number of lymph nodes dissected affected the OS in T1-4N0M0”, and explain this as follows: “First T1-4N0M0 is the early stage of the tumor without lymph node metastasis, and second, for early tumors, surgeons may not be as aggressive as for advanced tumors and may cause less damage to the body”.

Nevertheless, the harvest of a significant number of lymph nodes from the specimen and its study by the pathologist is an extremely important part in the comprehensive treatment of CRC. It has been established that LNY < 12 has the risk of downstaging[11]. The studies on recurrence and survival of CRC must include patients with long follow-up to assure their disease-free survival. Thus, this exhaustive nodal harvesting is not to be considered “impractical”.

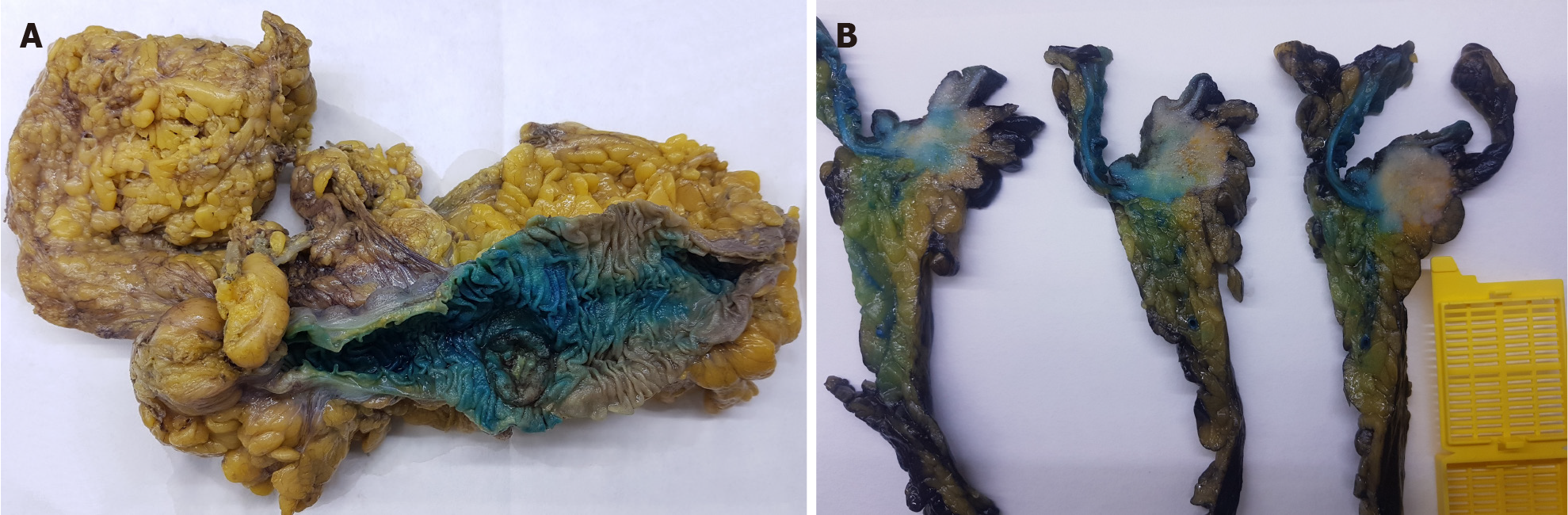

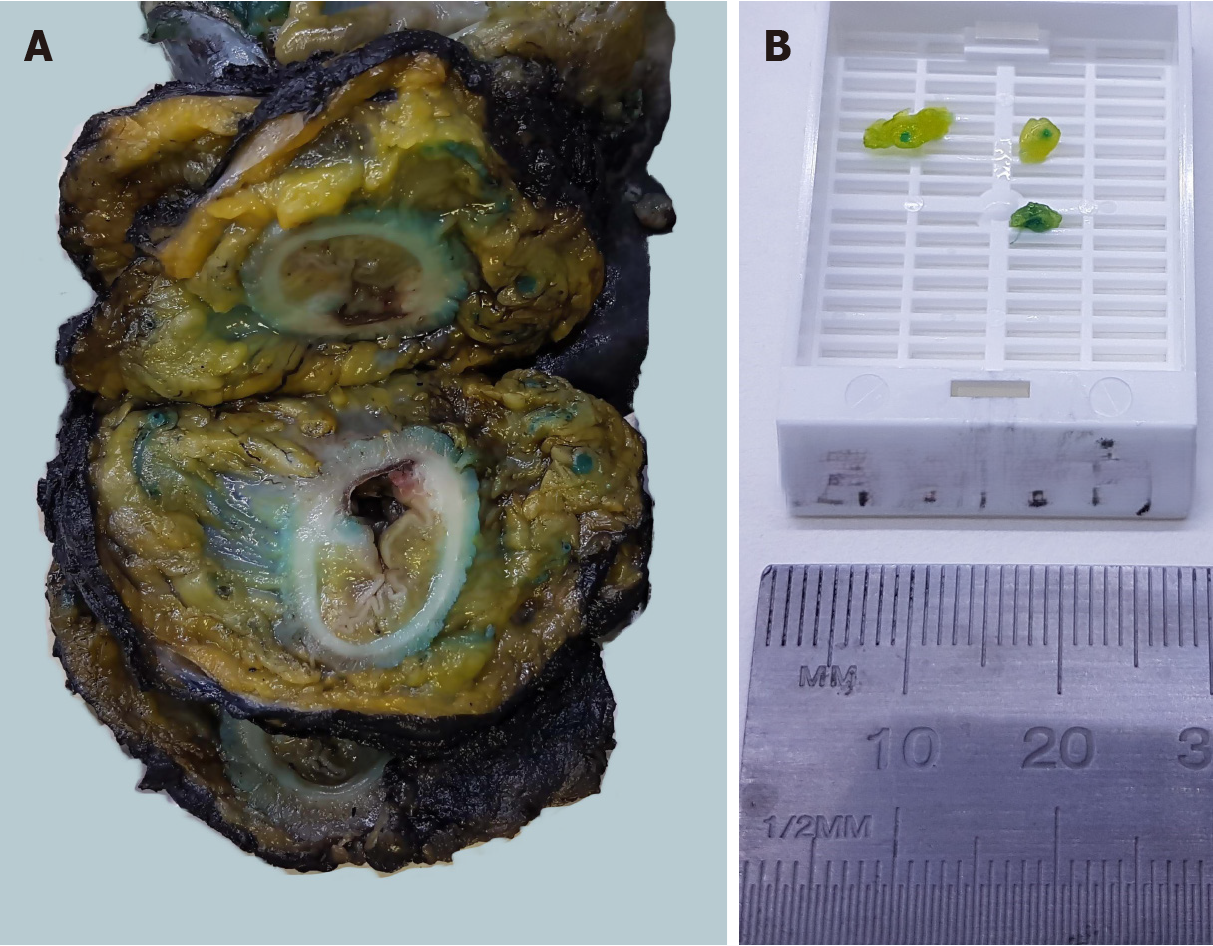

At our institution, the surgeon performs an intraarterial injection of methylene blue into the mescolon or mesorectum on bench just after the surgical procedure. The pathologist then proceeds with a second injection adding formaldehyde to methylene blue at the reception of the specimen. This technique has provided an increase in LNY from 18 nodes ± 3 to 34 nodes ± 11.5 (Figures 1 and 2).

Furthermore, T1-2N0M0 represents the early stage of the tumor without lymph node metastasis, but T3-4N0M0 represents stage II disease, and at this point it is not considered an early stage and adjuvant therapy will be indicated. Both T status and N status are known after surgical resection. Therefore, the surgical technique should aim to obtain the best surgical specimen. The exquisite handling of tissues and a skilled surgical technique will allow proper assessment of the specimen by the pathologist who will report the accurate TNM stage.

Hence, when He et al[13] concluded in their article that an insufficient number of lymph nodes dissected should not be a cause for alarm during surgery, one should not conclude that it is a sufficient surgical procedure for obtaining an inappropriate surgical specimen, and it may be a warning for the pathologist to strive to obtain the recommended lymph nodes for histological examination.

Improved surgical technique influences the oncological results. The number of lymph nodes removed by the surgeon and examined by the pathologist has been considered a potentially quantifiable surrogate marker for adequacy of the tumor resection technique. A higher LNY, regardless of positive or negative status, is associated with improved OS, disease free survival, and reduced risk of recurrence[14].

Nevertheless, LNY depends on several factors: The patient, the tumor biology, the surgeon, and the pathologist. Hence, LNY is not a reliable marker for assessment of the quality of surgical resection. We agree with Baxter that “although lymph node count may certainly play a role in quality improvement strategies, it is key that the importance of this indicator is not overemphasized”[15].

In addition to the discussion of LNY as a surrogate of the quality of surgery, the obtained surgical specimen has to involve a correct anatomical colon segment, consistent with the location of the neoplasm to be resected, and including an en bloc undamaged mesentery, obtained through a dissection between coalescence planes heralded by the areolar tissue which separates anatomical structures in avascular planes. When the tumor is located at the rectum, an appropriate mesorectal excision will be performed through what Bill Heald called the Holy plane. In doing so, all the existing lymph nodes belonging to that area of colon will be removed, and the surgery will be carried on with the lowest possible blood loss.

In conclusion, lymph node dissection in oncological surgery, particularly in CRC surgery, may play a minimal therapeutic role in locoregional control of the disease, and has a significant role in staging the cancer which is of upmost importance to decide on subsequent management of the patient.

| 1. | Halsted WS. I. The Results of Operations for the Cure of Cancer of the Breast Performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital from June, 1889, to January, 1894. Ann Surg. 1894;20:497-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;1:1479-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1867] [Cited by in RCA: 1914] [Article Influence: 49.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zaheer S, Pemberton JH, Farouk R, Dozois RR, Wolff BG, Ilstrup D. Surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the rectum. Ann Surg. 1998;227:800-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Syk E, Torkzad MR, Blomqvist L, Nilsson PJ, Glimelius B. Local recurrence in rectal cancer: anatomic localization and effect on radiation target. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:658-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sigurdson ER. Lymph node dissection: is it diagnostic or therapeutic? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:965-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Quezada-Diaz FF, Smith JJ. Neoadjuvant Therapy for Rectal Cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2022;31:279-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Birk D, Beger HG. Lymph-node dissection in pancreatic cancer -- what are the facts? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1999;384:158-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Eskander MF, de Geus SW, Kasumova GG, Ng SC, Al-Refaie W, Ayata G, Tseng JF. Evolution and impact of lymph node dissection during pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2017;161:968-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1604-1608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1124] [Cited by in RCA: 1144] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tong GJ, Zhang GY, Liu J, Zheng ZZ, Chen Y, Niu PP, Xu XT. Comparison of the eighth version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer manual to the seventh version for colorectal cancer: A retrospective review of our data. World J Clin Oncol. 2018;9:148-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, Conley B, Cooper HS, Hamilton SR, Hammond ME, Henson DE, Hutter RV, Nagle RB, Nielsen ML, Sargent DJ, Taylor CR, Welton M, Willett C. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:979-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 810] [Cited by in RCA: 867] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Argilés G, Tabernero J, Labianca R, Hochhauser D, Salazar R, Iveson T, Laurent-Puig P, Quirke P, Yoshino T, Taieb J, Martinelli E, Arnold D; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Localised colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1291-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 803] [Article Influence: 160.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | He F, Qu SP, Yuan Y, Qian K. Lymph node dissection does not affect the survival of patients with tumor node metastasis stages I and II colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2024;16:2503-2510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen K, Collins G, Wang H, Toh JWT. Pathological Features and Prognostication in Colorectal Cancer. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:5356-5383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Baxter NN. Is lymph node count an ideal quality indicator for cancer care? J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:265-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |