Published online Jul 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i7.1522

Peer-review started: November 25, 2022

First decision: February 20, 2023

Revised: February 22, 2023

Accepted: March 27, 2023

Article in press: March 27, 2023

Published online: July 27, 2023

Processing time: 238 Days and 13.6 Hours

The outcomes of liver transplantation (LT) from different grafts have been studied individually and in combination, but the reports were conflicting with some researchers finding no difference in both short-term and long-term outcomes between the deceased donor split LT (DD-SLT) and living donor LT (LDLT).

To compare the outcomes of DD-SLT and LDLT we performed this systematic review and meta-analysis.

This systematic review was performed in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines. The following databases were searched for articles comparing outcomes of DD-SLT and LDLT: PubMed; Google Scholar; Embase; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; and Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/). The search terms used were: “liver transplantation;” “liver transplant;” “split liver transplant;” “living donor liver transplant;” “partial liver transplant;” “partial liver graft;” “ex vivo splitting;” and “in vivo splitting.”

Ten studies were included for the data synthesis and meta-analysis. There were a total of 4836 patients. The overall survival rate at 1 year, 3 years and 5 years was superior in patients that received LDLT compared to DD-SLT. At 1 year, the hazard ratios was 1.44 (95% confidence interval: 1.16-1.78; P = 0.001). The graft survival rate at 3 years and 5 years was superior in the LDLT group (3 year hazard ratio: 1.28; 95% confidence interval: 1.01-1.63; P = 0.04).

This meta-analysis showed that LDLT has better graft survival and overall survival when compared to DD-SLT.

Core Tip: This meta-analysis is one of the few studies in the literature to compare the deceased donor split liver transplantation (DD-SLT) and living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) patients in terms of clinical outcomes. Although this study had some limitations, this meta-analysis showed that LDLT has better graft survival and overall survival compared to DD-SLT. The allograft in LDLT also had superior outcomes compared to DD-SLT in terms of acute rejection.

- Citation: Garzali IU, Akbulut S, Aloun A, Naffa M, Aksoy F. Outcome of split liver transplantation vs living donor liver transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(7): 1522-1531

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i7/1522.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i7.1522

Liver transplantation (LT) is the treatment of choice for end stage liver diseases as well as selected liver malignancies and metabolic disorders. Since LT became accepted as a therapeutic procedure, there was an increase in the number of patients listed to receive LT. This resulted in a significant organ shortage with high waiting list mortality[1,2]. To alleviate the organ shortage, efforts were made to increase donor pool. Some of these efforts include: donation after cardiac death; extended criteria donors; deceased donor-split LT (DD-SLT); living donor LT (LDLT); and domino or sequential LT.

The first DD-SLT was conducted in 1988 by Pichlmayr et al[3] when they split the liver into two grafts: one for a child (left lateral segment) and the other for an adult (extended right trisegments). Bismuth et al[4] in 1989 reported another case of SLT for 2 patients with acute liver failure. The first series was reported in 1990 by Emond et al[5] of the University of Chicago. They described their experience with nine DD-SLT procedures in 18 pediatric and adult recipients. Shortly after the first DD-SLT, Raia et al[6] and Strong et al[7] conducted the first reported LDLT. Since then, both types of LT have gained acceptance, with DD-SLT now being utilized for two carefully selected adults.

The outcome of LDLT and SLT have been studied individually and in combination, but the reports were conflicting with some researchers finding no difference in both short-term and long-term outcomes between the two types of LT[8-10]. However, there are some reports of superiority of one over the other[11-13]. One of the common themes in all these reports is the small sample size, which may serve as a major limitation to any conclusion drawn from these studies. We aimed to perform this systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the outcomes of DD-SLT and LDLT.

This systematic review was performed in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines. The protocol for this systematic review was prospectively registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO (CRD42022350273). This study did not include patient participation. Therefore, ethical clearance from the institutional review board and patient informed consent were not sought.

Two reviewers (SA and FA) independently searched several databases for articles comparing outcomes of LDLT and DD-SLT. The databases were: PubMed; Google Scholar; Embase; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; and Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/). The search was conducted from July 15, 2022 through August 3, 2022. The search terms used were ”liver transplantation;” “liver transplant;” “split liver transplant;” “living donor liver transplant;” partial liver transplant;” “partial liver graft;” “ex vivo splitting;” and “in vivo splitting.” Boolean logic was used to combine the keywords. Related articles and reference lists were searched to avoid omission. In case of conflict between the two reviewers, a third reviewer resolved the conflict.

Studies that fulfilled the following criteria were included for the review: (1) Studies published from 1990 to date; (2) Studies that compared the outcomes of DD-SLT and LDLT; and (3) Studies published in English. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Editorials and commentaries; (2) Publications in other languages apart from English; (3) Lack of relevant data or insufficient data; and (4) Total study population less than 10 patients.

To assess the risk of bias, two authors analyzed the quality of each included study independently using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Case-Control Studies. The maximum score on this scale was 12. Studies were considered good when scored ≥ 9, fair when scored 6-8 and poor when scored ≤ 5. The risk of publication bias was assessed by inspection of funnel plot for symmetry.

Data were extracted by two reviewers separately (AA and MN). The data extracted include: name of authors; year of publication; number of patients included in DD-SLT and LDLT; age of recipients in each group; sex of recipients in each group; model for end-stage liver disease score of the recipients in each group; cold ischemic time (CIT) in each group; overall biliary complications; hepatic artery thrombosis; portal vein thrombosis; early postoperative mortality; acute graft rejection; and 1-year, 3-year and 5-year overall patient and graft survival. Disagreements between reviewers were discussed with a third reviewer (IUG) to reach an agreement.

The primary outcome we considered in this meta-analysis was patient and graft survival. Secondary outcomes include CIT in each group, overall biliary complications, hepatic artery thrombosis, portal vein thrombosis, early postoperative mortality and acute graft rejection.

All statistical analyses were performed using RevMan software (version 5.4.1). For dichotomous variables, the pooled relative risk (RR) was calculated with 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous variables, the weighted mean difference or standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95%CI was calculated. We used a fixed-effects model to calculate the pooled effect sizes if the data were not significantly heterogeneous. Otherwise, a random-effects model was used. Heterogeneity was evaluated by I2 statistics. I2 > 50% was considered as statistically significant heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was used by omitting each included study in the meta-analysis to identify the main source of heterogeneity. Standard deviation was computed from standard error, CI or from P values if it was not given directly in the articles. If the article included did not provide the mean value, we used the Wan et al[14] method of computing mean from median and range. In the survival analysis, the log hazard ratio and variance were obtained by the Tierney et al[15] method of computing the percentage survival at a given time. Publication bias was evaluated using the funnel plot and Egger’s test if 10 or more studies were included in the meta-analysis of a particular outcome as recommended by the Cochrane handbook.

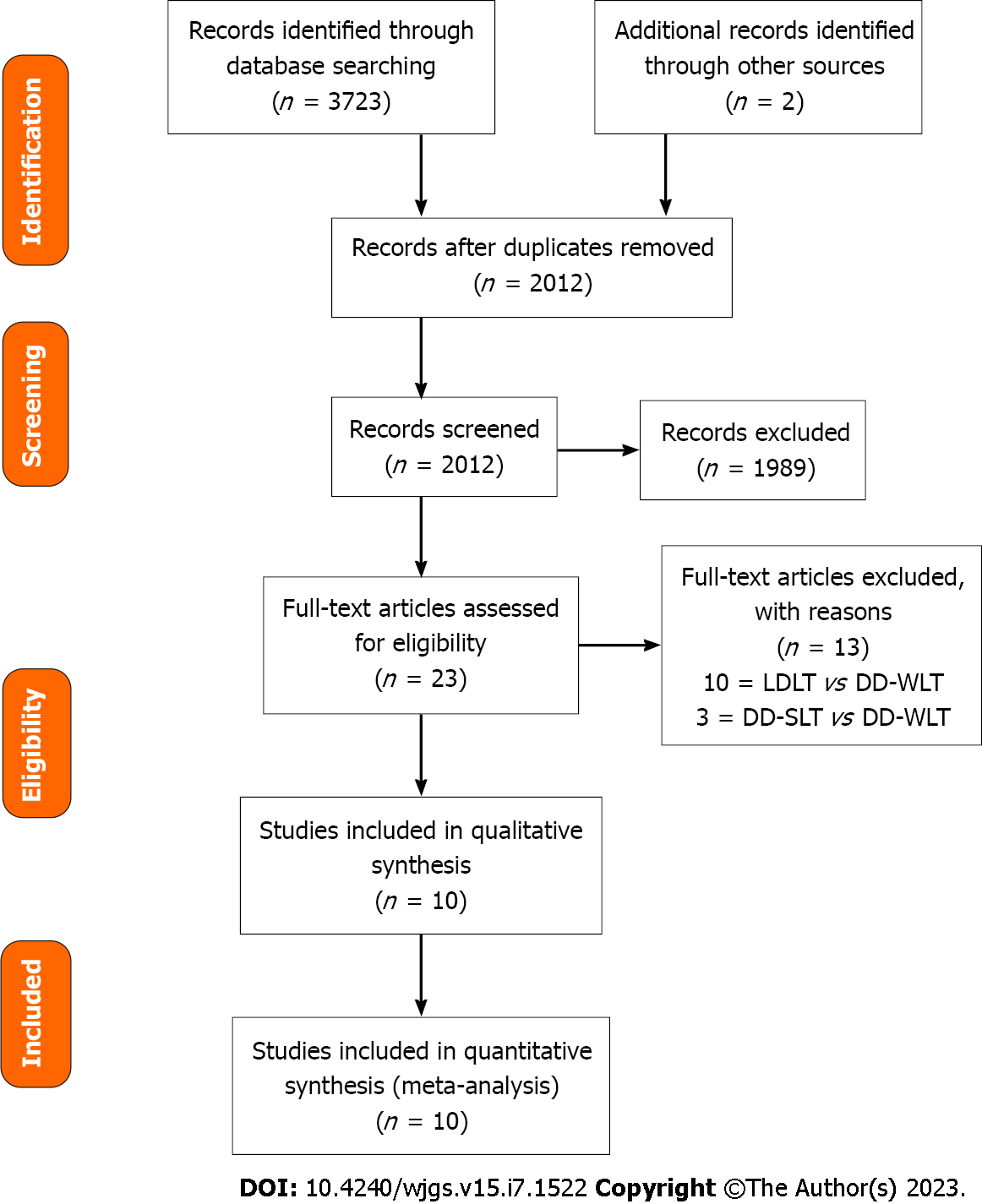

During the initial search, 3723 references were identified. Among the identified references, there were 1711 duplicates and 1989 unrelated articles, and these were excluded (Figure 1). After exclusion, there were 23 remaining articles, and these were retrieved for complete assessment. Thirteen references were excluded because the study populations were different. Ten studies[16-25] were included for the data synthesis and meta-analysis. The studies included were all retrospective studies dated between 2005 and 2022. Overall, there were a total of 4836 patients with 3006 of them undergoing LDLT, while 1830 received DD-SLT. Five of the studies were conducted in the United States[17,19,21-23], and the remaining five studies were conducted in Italy[20], Belgium[18], South Korea[25], France[24] and Iran[16].

Four of the studies were of good quality, while six were of fair quality based on the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Case-Control. Details of selected studies were displayed in Table 1.

| Ref. | Year | Sample size | Quality assessment score | Quality | |

| LDLT | DD-SLT | ||||

| Dalzell et al[17] | 2022 | 403 | 508 | 9 | Good |

| Sebagh et al[24] | 2006 | 38 | 20 | 8 | Fair |

| Saidi et al[23] | 2011 | 1715 | 557 | 9 | Good |

| Yoon et al[25] | 2022 | 56 | 63 | 7 | Fair |

| Giacomoni et al[20] | 2005 | 18 | 9 | 7 | Fair |

| Humar et al[22] | 2008 | 69 | 31 | 9 | Good |

| Darius et al[18] | 2014 | 203 | 47 | 8 | Fair |

| Diamond et al[19] | 2007 | 360 | 261 | 9 | Good |

| Bahador et al[16] | 2009 | 54 | 20 | 8 | Fair |

| Hong et al[21] | 2009 | 90 | 181 | 7 | Fair |

The two groups did not show any statistical significance in age distribution (SMD: 0.30; 95%CI: 0.44-1.04; P = 0.43). The sex distribution however differed between the two groups with more males receiving DD-SLT compared to LDLT (RR: 0.81; 95%CI: 0.71-0.93; P = 0.003). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding model for end-stage liver disease/pediatric end-stage liver disease score (SMD: 0.35; 95%CI: 0.20-0.91; P = 0.21). The CIT was significantly different between the two groups, with the DD-SLT group having a longer CIT (SMD: 8.57; 95%CI: 0.05-17.09; P < 0.001).

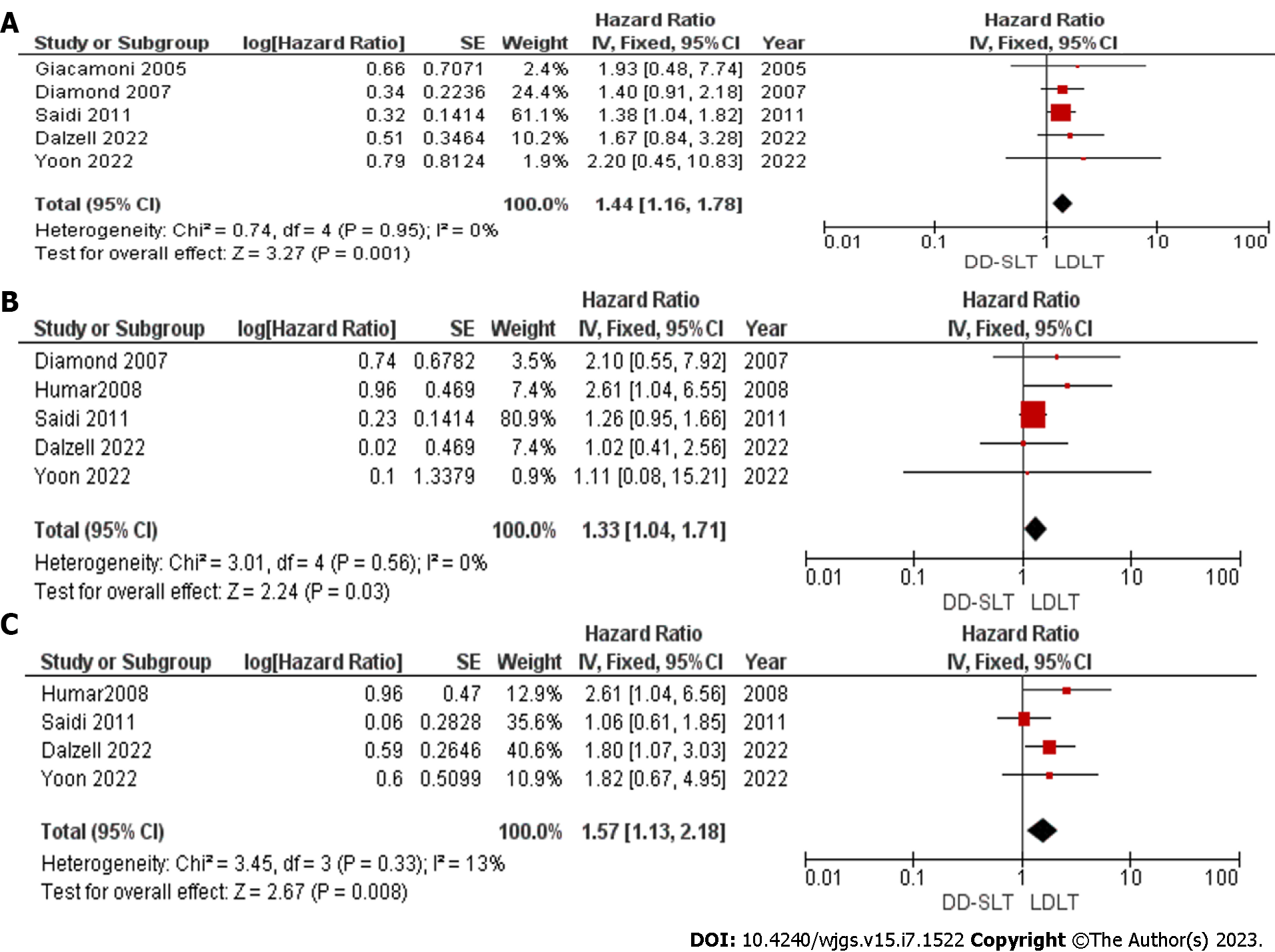

Overall survival: The overall survival rate at 1 year, 3 years and 5 years were compared and reported in five studies[17,19,20,23,25], five studies[17,19,22,23,25] and four studies[17,22,23,25], respectively. The overall survival at 1 year, 3 years and 5 years was superior in patients that received LDLT compared to DD-SLT. At 1-year, the hazard ratio was 1.44 (95%CI: 16-1.78; P = 0.001). The detailed HR and P value are presented in Figure 2. We did not assess publication bias as less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

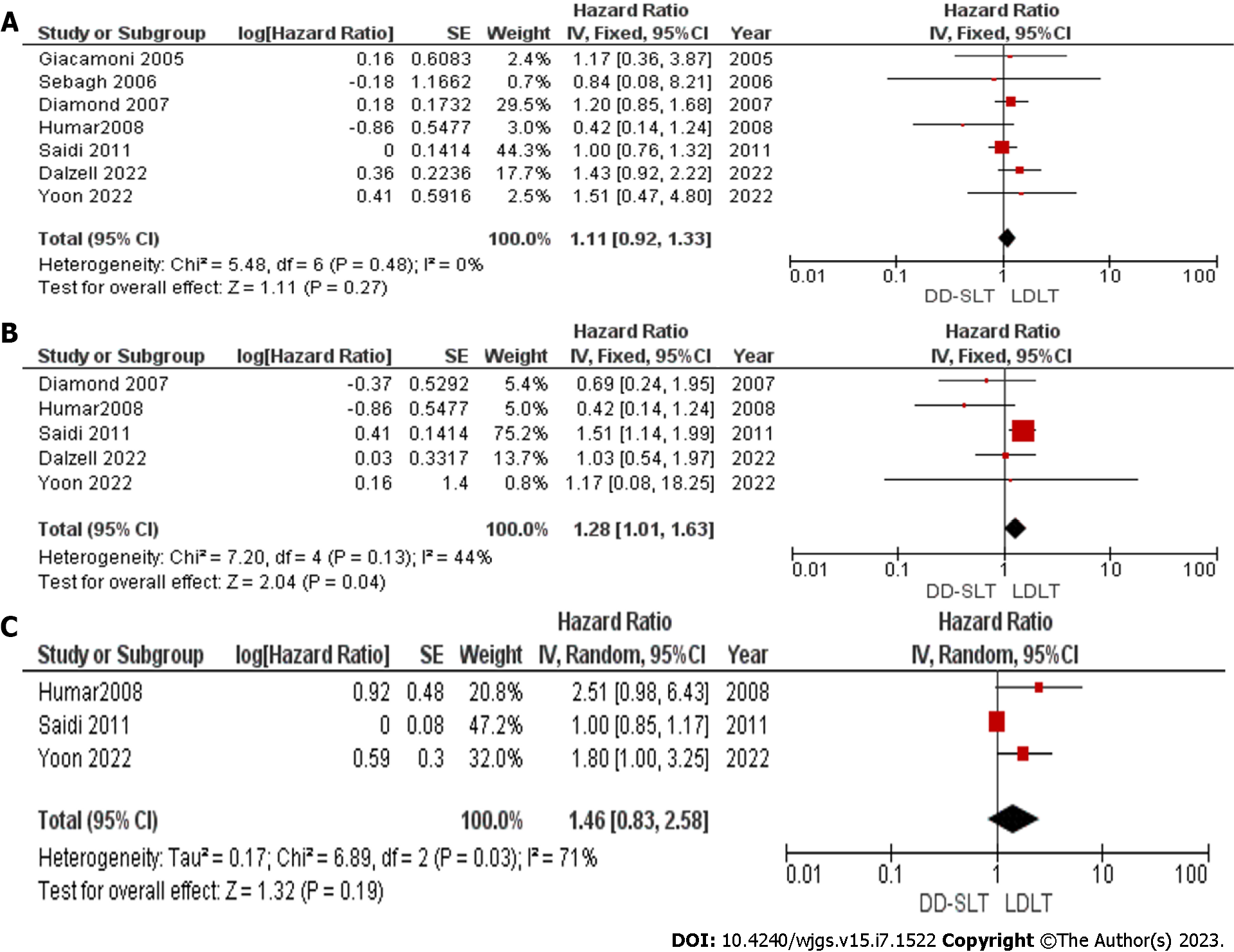

Graft survival: The graft survival rate at 1 year, 3 years and 5 years were compared and reported in seven studies[17,19,20,22-25], five studies[17,19,22,23,25] and three studies[22,23,25], respectively. Graft survival between the two groups was not significantly different between the two groups at 1 year (HR: 1.11; 95%CI: 0.92-1.33; P = 0.27). However, at 3 years, the graft survival in the LDLT group was superior to graft survival in the DD-SLT group (HR: 1.28; 95%CI: 1.01-1.63; P = 0.04). The difference was not sustained as the graft survival at 5 years showed no difference between DD-SLT and LDLT (HR: 1.46; 95%CI: 0.83-2.58 ; P > 0.05).

The detailed meta-analysis is presented in Figure 3. There was significant heterogeneity among the studies used for meta-analysis of 5-year graft survival with I2 = 71%. The main source of heterogeneity was the study by Saidi et al[23]. After eliminating this study from the meta-analysis, the heterogeneity vanished with I2 = 0%. We also observed a significant difference in the 5-year graft survival in favor of those that received LDLT (HR: 1.98; 95%CI: 1.20-3.26; P = 0.007). We did not assess publication bias as less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Primary non-function: Primary non-function (PNF) assessment was completed in three studies[17,21,22] comprising 720 patients in the DD-SLT group and 562 patients in the LDLT group. PNF occurred among 20 patients in DD-SLT, but in the LDLT group only 11 patients developed PNF. There was no significant heterogeneity between the studies with I2 = 0%. Therefore, the fixed effect was used in estimating pooled effect. The pooled RR was 1.13 (95%CI: 0.57-2.25; P = 0.72), which was not statistically significant. We did not assess publication bias as less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Vascular complications: Hepatic artery thrombosis was reported in seven studies[16,17,19-21,24] consisting of 1062 patients in the DD-SLT group and 1019 patients in the LDLT group. Hepatic artery thrombosis occurred in 56 patients in the DD-SLT group, but in the LDLT group 66 patients developed hepatic artery thrombosis. There was no significant heterogeneity between the studies with I2 = 0%. Therefore, the fixed effect was used in estimating pooled effect. The pooled RR was 0.90 (95%CI: 0.64-1.26; P = 0.53), which was not statistically significant. We did not assess publication bias as less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Portal vein thrombosis was reported in four studies[17,19,21,25] comprising 1013 patients in the DD-SLT group and 909 patients in LDLT group. Portal vein thrombosis occurred in 36 patients in the DD-SLT group and among 43 patients in the LDLT group. The heterogeneity between studies was not significant with I2 = 0%, and the fixed effect was used to estimate pooled effect. The pooled RR was 0.91 (95%CI: 0.59-1.38; P = 0.65), which was not statistically significant. We did not assess publication bias as less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Retransplantation: The rate of re-LT was reported in five studies[17,19-21,24] consisting of 979 patients in the DD-SLT group and 909 patients in the LDLT group. Re-LT was needed in 82 patients in the DD-SLT group, and 71 patients needed re-LT in the LDLT group. There was no significant heterogeneity between studies with I2 = 0%, and the fixed effect was used to estimate pooled effect. The pooled RR was 0.97 (95%CI: 0.72-1.31; P = 0.84). We did not assess publication bias as less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Acute rejection was compared between the two groups in three studies[16,22,24] comprising 71 patients in the DD-SLT group and 161 patients in the LDLT group. Acute rejection was observed in 17 patients among the DD-SLT group and 22 patients in the LDLT group. There was no heterogeneity between the studies with the I2 = 0%. The difference was significant (RR: 1.75; 95%CI: 1.04-2.94; P = 0.04). The detailed meta-analysis is presented in Figure 4. We did not assess publication bias as less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Eight studies[16-21,24,25] compared biliary complications between the DD-SLT and LDLT groups. In the studies, 1109 patients received DD-SLT and 1222 patients received LDLT. There was significant heterogeneity between the studies. Therefore, the random effect was used to test for the overall effect. The pooled RR was 0.86 (95%CI: 0.49-1.52). There was no difference between the two groups (P = 0.60). We did not assess publication bias as less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Early postoperative mortality within 3 mo was reported in four studies[19,20,24,25] consisting of 353 patients in the DD-SLT group and 472 patients in the LDLT group. There was no heterogeneity between the studies with I2 = 0%. There was a significant difference in the mortality between the two group with the DD-SLT group having more mortality (RR: 1.95; 95%CI: 1.11-3.42; P = 0.02). We did not assess publication bias as less than 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

In this meta-analysis, we compared the short-term and long-term outcomes of LT between those that received LDLT and those that received DD-SLT. The primary outcome we compared was overall survival, and the meta-analysis revealed that patients that received LDLT had a superior overall survival compared to those that received DD-SLT. At 1-year post-LT, there was a difference in the overall survival between the two groups with an HR of 1.44 (95%CI: 1.16-1.78; P = 0.001). This superiority was sustained through the 3rd and 5th years after LT. Our findings are similar to the meta-analysis conducted by Barbetta et al[26] among pediatric patients receiving partial liver allograft. These findings may be attributed to the fact that most LDLT procedures are elective. Therefore, the recipients are of better health status. In addition, there is a shorter CIT in LDLT. Gavriilidis et al[8] reported contrasting findings in their meta-analysis of adults receiving LDLT vs DD-SLT. There findings may not be significant because only three studies were analyzed after 1 year and two studies were analyzed after 3 years and 5 years. The included studies also exhibited marked heterogeneity as I2 was > 50%.

Graft survival showed a complex pattern in our meta-analysis. The graft survival showed superiority in the LDLT group after 1 year, 3 years and 5 years based on the forest plots. This difference was only significant at 3 years. There was marked heterogeneity between studies used for the meta-analysis of the 5-year graft survival with I2 = 71%. The main source of heterogeneity was the study by Saidi et al[23] After eliminating this study from the meta-analysis, the heterogeneity vanished with I2 = 0%. We also observed a significant difference in the 5-year graft survival in favor of those that received LDLT (HR: 1.98; 95%CI: 1.20-3.26; P = 0.007). The findings of Gavriilidis et al[8] showed no significant differences in graft survival between the two groups at 1 year, 3 years and 5 years.

We compared early vascular and technical complications like hepatic artery thrombosis, portal vein thrombosis and biliary complications after LT between the groups that received DD-SLT and LDLT. Our findings revealed there were no significant differences between the two groups regarding these complications. These findings were also presented in the meta-analysis conducted by Gavriilidis et al[8]. Similarities in these outcomes between LDLT and DD-SLT were a result of the procedures being similar with the primary difference being the status of the donor. In LDLT, the procedure is performed on live patients and only a part of the liver is harvested for use on a single recipient. While in DD-SLT, the procedure is performed on a brain dead donor, and the liver is split into to two parts and received by two recipients.

Early post-LT mortality occurring within 3 mo of LT was also compared between recipients of DD-SLT and recipients of LDLT. Our meta-analysis revealed that recipients of LDLT had a better outcome with less early mortality compared to DD-SLT. The mortality pattern may reflect the pre-LT status of the patients and that most DD-SLT procedures were performed as emergency surgeries.

One of the causes of graft loss in the setting of LT is acute rejection. Shaked et al[27] reported clinically evident acute rejection in 26% of 593 patients who received LT. In the same study, biopsy proven acute rejection was seen in 27% of the study population. Our meta-analysis compared acute rejection between DD-SLT and LDLT, and we found that LDLT was associated with less acute rejection episodes. This is similar to the findings of Barbetta et al[26] in a meta-analysis comparing outcomes of LT among pediatric recipients of partial liver allografts. The reasons for less acute rejection in the LDLT group may include the following: donor organs with minimal exposure to brain death associated stress; minimal injuries associated with prolonged CIT; and human leukocyte antigen matching among biologically related individuals.

Another cause of graft loss after LT is PNF, which may ultimately require re-LT. The incidence of PNF after LT has been reported as 2.2%-3.5%[28,29], but an incidence of up to 27% has been reported by González et al[30]. In this meta-analysis, we compared PNF and re-LT between recipients of LDLT and recipients of DD-SLT. Our finding revealed no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding PNF and re-LT.

This study had a few limitations. The first was that all of the studies included in this study included retrospective case-control studies. However, it is very difficult to resolve this limitation, and designing a prospective study on this subject involves ethical problems. It is unethical not to transplant a patient who has a chance for DD-SLT and to force him to receive LDLT. Conversely, keeping a patient with a chance of LDLT on the waiting list for an academic study is also ethically problematic. Therefore, it does not seem possible to conduct a prospective study on this issue at the present time. Second, since there is no randomization in retrospective studies, it is not expected that the groups will be homo

This meta-analysis is one of the few studies in the literature to compare DD-SLT and LDLT patients in terms of clinical outcomes. Although this study has some limitations, this meta-analysis has shown that LDLT has a better graft survival and overall survival compared to DD-SLT. The allograft in LDLT also has a superior outcome compared to DD-SLT in terms of acute rejection.

The outcome of liver transplantation (LT) may be affected by the type of graft implanted in the recipient. The graft may be from a deceased donor or from a living donor. Deceased donor graft may be whole graft or split graft.

To encourage the utilization of deceased donor split LT (DD-SLT) to increase the donor pool in LT.

To perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the outcome of DD-SLT and living donor LT (LDLT).

This systematic review was performed in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines. A search was performed in research databases for articles comparing outcomes of DD-SLT and LDLT. Data were extracted from these studies for meta-analysis.

Patients that received LDLT had a better overall survival and graft survival.

This meta-analysis showed that LDLT has a better graft survival and overall survival when compared to DD-SLT.

To put the study in perspective, the type of graft affected the outcome of LT. Living donor graft has a superior outcome to deceased donor split graft.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Koganti SB, United States; Kowalewski G, Poland; Li HL, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Lee DH, Park YH, Choi SW, Nam KH, Choi ST, Kim D. The impact of Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score on deceased donor liver transplant outcomes in low volume liver transplantation center: a retrospective and single-center study. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2021;101:360-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mehta N. Liver Transplantation Criteria for Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Including Posttransplant Management. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2021;17:332-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pichlmayr R, Ringe B, Gubernatis G, Hauss J, Bunzendahl H. [Transplantation of a donor liver to 2 recipients (splitting transplantation)--a new method in the further development of segmental liver transplantation]. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1988;373:127-130. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bismuth H, Morino M, Castaing D, Gillon MC, Descorps Declere A, Saliba F, Samuel D. Emergency orthotopic liver transplantation in two patients using one donor liver. Br J Surg. 1989;76:722-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Emond JC, Whitington PF, Thistlethwaite JR, Cherqui D, Alonso EA, Woodle IS, Vogelbach P, Busse-Henry SM, Zucker AR, Broelsch CE. Transplantation of two patients with one liver. Analysis of a preliminary experience with 'split-liver' grafting. Ann Surg. 1990;212:14-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Raia S, Nery JR, Mies S. Liver transplantation from live donors. Lancet. 1989;2:497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Strong RW, Lynch SV, Ong TH, Matsunami H, Koido Y, Balderson GA. Successful liver transplantation from a living donor to her son. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1505-1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 604] [Cited by in RCA: 545] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gavriilidis P, Azoulay D, Sutcliffe RP, Roberts KJ. Split versus living-related adult liver transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2019;404:285-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hackl C, Schmidt KM, Süsal C, Döhler B, Zidek M, Schlitt HJ. Split liver transplantation: Current developments. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:5312-5321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hann A, Osei-Bordom DC, Neil DAH, Ronca V, Warner S, Perera MTPR. The Human Immune Response to Cadaveric and Living Donor Liver Allografts. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Goldaracena N, Marquez M, Selzner N, Spetzler VN, Cattral MS, Greig PD, Lilly L, McGilvray ID, Levy GA, Ghanekar A, Renner EL, Grant DR, Selzner M. Living vs. deceased donor liver transplantation provides comparable recovery of renal function in patients with hepatorenal syndrome: a matched case-control study. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:2788-2795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Montenovo MI, Bambha K, Reyes J, Dick A, Perkins J, Healey P. Living liver donation improves patient and graft survival in the pediatric population. Pediatr Transplant. 2019;23:e13318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zamora-Valdes D, Leal-Leyte P, Kim PT, Testa G. Fighting Mortality in the Waiting List: Liver Transplantation in North America, Europe, and Asia. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16:480-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3433] [Cited by in RCA: 7051] [Article Influence: 641.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4738] [Cited by in RCA: 4956] [Article Influence: 275.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bahador A, Salahi H, Nikeghbalian S, Dehghani SM, Dehghani M, Kakaei F, Kazemi K, Rajaei E, Gholami S, Malek-Hosseini SA. Pediatric liver transplantation in Iran: a 9-year experience. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2864-2867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dalzell C, Vargas PA, Soltys K, Dipaola F, Mazariegos G, Oberholzer J, Goldaracena N. Living Donor Liver Transplantation vs. Split Liver Transplantation Using Left Lateral Segment Grafts in Pediatric Recipients: An Analysis of the UNOS Database. Transpl Int. 2022;36:10437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Darius T, Rivera J, Fusaro F, Lai Q, de Magnée C, Bourdeaux C, Janssen M, Clapuyt P, Reding R. Risk factors and surgical management of anastomotic biliary complications after pediatric liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:893-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Diamond IR, Fecteau A, Millis JM, Losanoff JE, Ng V, Anand R, Song C; SPLIT Research Group. Impact of graft type on outcome in pediatric liver transplantation: a report From Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation (SPLIT). Ann Surg. 2007;246:301-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Giacomoni A, De Carlis L, Lauterio A, Slim AO, Aseni P, Sammartino C, Mangoni I, Belli LS, De Gasperi A. Right hemiliver transplant: results from living and cadaveric donors. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1167-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hong JC, Yersiz H, Farmer DG, Duffy JP, Ghobrial RM, Nonthasoot B, Collins TE, Hiatt JR, Busuttil RW. Longterm outcomes for whole and segmental liver grafts in adult and pediatric liver transplant recipients: a 10-year comparative analysis of 2,988 cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:682-9; discusion 689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Humar A, Beissel J, Crotteau S, Kandaswamy R, Lake J, Payne W. Whole liver versus split liver versus living donor in the adult recipient: an analysis of outcomes by graft type. Transplantation. 2008;85:1420-1424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Saidi RF, Jabbour N, Li Y, Shah SA, Bozorgzadeh A. Outcomes in partial liver transplantation: deceased donor split-liver vs. live donor liver transplantation. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:797-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sebagh M, Yilmaz F, Karam V, Falissard B, Ichaï P, Roche B, Castaing D, Guettier C, Samuel D, Azoulay D. Cadaveric full-size liver transplantation and the graft alternatives in adults: a comparative study from a single centre. J Hepatol. 2006;44:118-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yoon KC, Song S, Lee S, Kim OK, Hong SK, Yi NJ, Kim JM, Lee KW, Kim MS, Choi Y, Suh KS, Lee SK. Outcomes of Split Liver Transplantation vs Living Donor Liver Transplantation in Pediatric Patients: A 5-Year Follow-Up Study in Korea. Ann Transplant. 2022;27:e935682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Barbetta A, Butler C, Barhouma S, Hogen R, Rocque B, Goldbeck C, Schilperoort H, Meeberg G, Shapiro J, Kwon YK, Kohli R, Emamaullee J. Living Donor Versus Deceased Donor Pediatric Liver Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Transplant Direct. 2021;7:e767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shaked A, Ghobrial RM, Merion RM, Shearon TH, Emond JC, Fair JH, Fisher RA, Kulik LM, Pruett TL, Terrault NA; A2ALL Study Group. Incidence and severity of acute cellular rejection in recipients undergoing adult living donor or deceased donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:301-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Uemura T, Randall HB, Sanchez EQ, Ikegami T, Narasimhan G, McKenna GJ, Chinnakotla S, Levy MF, Goldstein RM, Klintmalm GB. Liver retransplantation for primary nonfunction: analysis of a 20-year single-center experience. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:227-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhang X, Zhang C, Huang H, Chen R, Lin Y, Chen L, Shao L, Liu J, Ling Q. Primary nonfunction following liver transplantation: Learning of graft metabolites and building a predictive model. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11:e483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | González FX, Rimola A, Grande L, Antolin M, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Fuster J, Lacy AM, Cugat E, Visa J, Rodés J. Predictive factors of early postoperative graft function in human liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1994;20:565-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |