Published online May 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i5.917

Peer-review started: October 9, 2022

First decision: December 12, 2022

Revised: December 22, 2022

Accepted: April 4, 2023

Article in press: April 4, 2023

Published online: May 27, 2023

Processing time: 228 Days and 21.3 Hours

Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) is an innovative surgical approach for the treatment of massive hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the key to successful planned stage 2 ALPPS is future liver remnant (FLR) volume growth, but the exact mechanism has not been elucidated. The correlation between regulatory T cells (Tregs) and postoperative FLR regeneration has not been reported.

To investigate the effect of CD4+CD25+ Tregs on FLR regeneration after ALPPS.

Clinical data and specimens were collected from 37 patients who developed massive HCC treated with ALPPS. Flow cytometry was performed to detect changes in the proportion of CD4+CD25+ Tregs to CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood before and after ALPPS. To analyze the relationship between peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ Treg proportion and clinicopathological information and liver volume.

The postoperative CD4+CD25+ Treg proportion in stage 1 ALPPS was negatively correlated with the amount of proliferation volume, proliferation rate, and kinetic growth rate (KGR) of the FLR after stage 1 ALPPS. Patients with low Treg proportion had significantly higher KGR than those with high Treg proportion (P = 0.006); patients with high Treg proportion had more severe postoperative pathological liver fibrosis than those with low Treg proportion (P = 0.043). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve between the percentage of Tregs and proli

CD4+CD25+ Tregs in the peripheral blood of patients with massive HCC at stage 1 ALPPS were negatively correlated with indicators of FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS and may influence the degree of fibrosis in patients’ livers. Treg percentage was highly accurate in predicting the FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS.

Core Tip: To investigate the mechanisms affecting future liver remnant (FLR) after stage 1 associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS), this study was conducted by analyzing clinical data and peripheral blood specimens collected from hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with ALPPS. The results showed that CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) in peripheral blood after stage 1 ALPPS was negatively correlated with the index of FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS and may influence the extent of liver fibrosis in patients. The percentage of Tregs was highly accurate in predicting FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS.

- Citation: Wang W, Ye CH, Deng ZF, Wang JL, Zhang L, Bao L, Xu BH, Zhu H, Guo Y, Wen Z. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells decreased future liver remnant after associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(5): 917-930

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i5/917.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i5.917

Primary liver cancer is a common malignant tumor of the digestive system, with approximately 906000 new cases and 830000 deaths worldwide each year, making it an important health threat to the nation[1]. Surgical treatment of primary liver cancer is an important tool for the long-term survival of patients. For patients with primary liver cancer who are able to obtain radical resection, the 5-year survival rate can reach 60%-80%[2]. Due to the insidious onset of primary liver cancer, many patients are at an advanced stage at the time of initial diagnosis. Posthepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) may occur in massive hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) due to the large size of the tumor and the lack of volume of the future liver remnant (FLR) after direct resection. PHLF is a common postoperative complication and an important factor in the rate of liver resection, and is one of the leading causes of death after hepatectomy due to the lack of targeted and effective treatment[3]. FLR volume is a key factor in determining the safe performance of hepatectomy[4]. The emergence and development of portal vein embolization (PVE) has expanded the indications for hepatectomy in the treatment of massive HCC with insufficient FLR volume. PVE can increase FLR volume augmentation by blocking portal vein flow[5]. However, PVE promotes slow growth of the FLR, with postoperative complications reaching up to 20% and more than 20% of patients eventually unable to undergo reoperation[6]. In addition, the long waiting interval for PVE accelerates tumor progression[7].

To further accelerate the regeneration of the FLR and improve the surgical resection rate of massive HCC. German scholars reported in 2007 and in 2012 officially named and summarized an innovative hepatectomy, associating liver partition and portal vein ligation (PVL) for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS)[8]. Stage 1 ALPPS ligates the portal branches of the liver on the tumor side, whereas the right and left hemispheric parenchyma are separated and the hepatic artery and bile ducts are preserved. Once the FLR has reached a safe threshold, a right hemicolectomy or an enlarged right hemicolectomy is performed in stage 2 ALPPS. The technical approach to ALPPS is still being discussed and improved today, whereas research into the mechanisms of FLR regeneration in ALPPS is gradually increasing. An important feature of ALPPS is the rapid growth of the FLR in the stage 1 ALPPS, and the mechanisms behind this regeneration pattern are still unclear.

Natural regulatory T cells (Tregs) express surface CD4 and CD25, contain intracellular forkhead box P3 (FOXP3), and inhibit the proliferation of other cells in a contact-dependent manner[9]. It was first reported by Asano et al[10] that most mouse natural Tregs migrate out of the thymus on the 3rd day after birth; therefore, thymectomy on the 3rd day induces an autoinflammatory state that predisposes to autoimmune disease. With the discovery of Tregs and the understanding of their immunosuppressive effects, evidence has accumulated that this cell population is decisively involved in the pathogenesis of various diseases, such as chronic viral and autoimmune liver disease and HCC[11]. In particular, CD4+CD25+ Tregs are thought to be responsible for the impaired immune response during chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Patients with chronic HBV infection are characterized by an increased proportion of CD4+CD25+ Tregs in the peripheral blood, which aggregate significantly in the liver, with a positive correlation between their frequency and serum HBV DNA load[12]. Similarly, in patients with persistent HCV infection, an increased frequency of CD4+CD25+ Tregs in the blood and liver has been reported[13].

In recent years, the role of Tregs in tissue and organ repair and regeneration has received much attention. Many studies have confirmed the use of Tregs in tissue and organ repair and regeneration[14]. As the liver is one of the organs that can be regenerated in the human body, the study of regeneration of the FLR in HCC patients after surgery has become a hot topic in hepatobiliary surgery. However, most of the studies at home and abroad have focused on the changes of CD4+CD25+ Tregs in peripheral blood and tumor in the development of HCC and their mechanisms of action. Studies on Tregs affecting FLR regeneration after hepatectomy have not been reported.

This study focused on the correlation between peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ Tregs and FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS in patients with HCC.

This study reviewed basic clinical data of patients with massive HCC treated with ALPPS at our medical center from March 2018 to September 2021. This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of our medical center [No. 2018 (KY-E-079)]. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) FLR/standard liver volume (SLV) < 30%-50%, treatment strategy based on the degree of liver fibrosis, willingness to treat, preoperative liver function status, and patients already receiving ALPPS; (2) Preoperative liver function Child grade A or B; (3) All patients had pathologically confirmed HCC after surgical resection; and (4) All patients had not undergone any targeted drug therapy, kinase drug therapy, or immunotherapy preoperatively.

Exclusion criteria were: Preoperative diagnosis of non-B viral HCC or autoimmune HCC; postoperative pathological diagnosis of bile duct cell carcinoma or benign findings; incomplete clinical case information and clinical specimens; and use of any targeted drug therapy, kinase drug therapy, and immunotherapy in the perioperative period.

Evaluation of liver volume and surgical procedure: In combination with computed tomography (CT) images, preoperative and postoperative liver volumes as well as FLR volumes were measured, calculated, and recorded for each patient with liver cancer undergoing ALPPS surgery using the digital software of intelligent/interactive qualitative and quantitative analyses (IQQA-Liver; EDDA Technology Inc., Princeton, NJ, United States). The formula for calculating SLV was: SLV = -794.41 + 1267.28 × body surface area (M2)[15]. Kinetic growth rate (KGR) was calculated according to the method in a previous study[16]. All patients were operated by the same surgical team. Stage 1 ALPPS was performed using an anterior approach combined with selective PVL and liver parenchymal compartment[16]. After stage 1 ALPPS, CT was reviewed periodically to assess the regeneration of the FLR. Stage 2 ALPPS is accepted after meeting the following safety criteria[17]: FLR/SLV ≥ 50% with severe fibrosis or cirrhosis, FLR/SLV ≥ 40% with mild/moderate fibrosis, and FLR/SLV ≥ 30% without liver fibrosis or cirrhosis.

Flow cytometry: Patients undergoing ALPPS had 1 mL heparin-anticoagulated venous blood drawn early in the morning on an empty stomach, and the main procedure was to isolate a suspension of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. Then 1 mL whole blood was taken and three times the volume of erythrocyte lysate was added. The solution was mixed well and lysed on ice for 15 min, followed by centrifugation at 450 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate was resuspended by adding two times the volume of red blood cell lysate, followed by centrifugation at 450 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and after resuspending the cells in 1 mL flow cytometry staining buffer, the cell suspension was filtered through a flow tube and the filtrate was placed on ice. Then 100 μL cell suspension was aspirated and 0.625 μL fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled mouse anti-human CD4 monoclonal antibody, 0.5 μL pulmonary embolism-labeled mouse anti-human CD25, and the corresponding isotype antibody immunoglobulin G1 in the same volume were added. The solution was incubated for 45 min in the dark, followed by the addition of 400 μL flow cytometry staining buffer and centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded and the cells were resuspended by adding 500 μL flow cytometry staining buffer. A combination of CD4 and CD25 was used to stain cells to count the percentage of CD4+CD25+ Tregs. Data were obtained and analyzed with Cell Quest software.

SPSS 20.0 statistical software was used for statistical analyses and GraphPad Prism 8.0 software for plotting. Comparisons between two groups were made using t-tests for measurement data; repeated measures data were compared using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA); and correlations were analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation test. The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was used to assess the predictive effect. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

From March 2018 to September 2020, a total of 37 patients with HCC undergoing ALPPS were included according to the screening criteria. There were 34 males and 3 females. The mean age was 45 ± 11 years. All patients had hepatitis B-associated HCC. The mean tumor diameter was 9.5 ± 4.2 cm. The preoperative FLR volume was (364.3 ± 74.5) cm3; preoperative FLR/SLV was 35.1% ± 7.0%; and preoperative liver volume/body mass ratio was 0.60% ± 0.13% (Tables 1 and 2).

| Variable | ALPPS, n = 37 |

| Age, yr | 45 (26-75) |

| Sex, women/man, n (%) | 3 (8.1)/34 (91.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.2 (17.99-30.09) |

| AFP, ≥ 400 ng/mL/< 400 ng/mL, n (%) | 19 (51.4)/18 (48.6) |

| Degree of liver fibrosis, n | |

| No fibrosis | 7 |

| Mild fibrosis | 2 |

| Moderate fibrosis/fibrosis | 8 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 20 (54.1) |

| MELD score | 5.12 (0.75-11.00) |

| ICGR15, % | 5.3 (1.3-18.8) |

| Child-Pugh class, A/B/C, n | 36/1/0 |

| BCLC staging, A/B/C, n | 10/7/20 |

| Variable | ALPPS - stage 1 | ALPPS - stage 2 |

| Operative time, min | 341 (229-496) | 300 (167-483) |

| Blood loss, mL | 328 (50-2600) | 792 (200-6000) |

| Blood transfusion, mL | 300 (0-900) | 250 (0-2150) |

| Postoperative bile leakage, n | ||

| No | 36 | 27 |

| Yes | 1 | 3 |

| Clavien-Dindo classification, n | ||

| I | 20 | 12 |

| II | 14 | 14 |

| III | 3 | 4 |

| IV | 0 | 0 |

| ISGLS classification, n | ||

| A | 21 | 9 |

| B | 16 | 18 |

| C | 0 | 1 |

| Ishak fibrosis score | / | 3 (1-6) |

| Ishak inflammation score | / | 5 (2-12) |

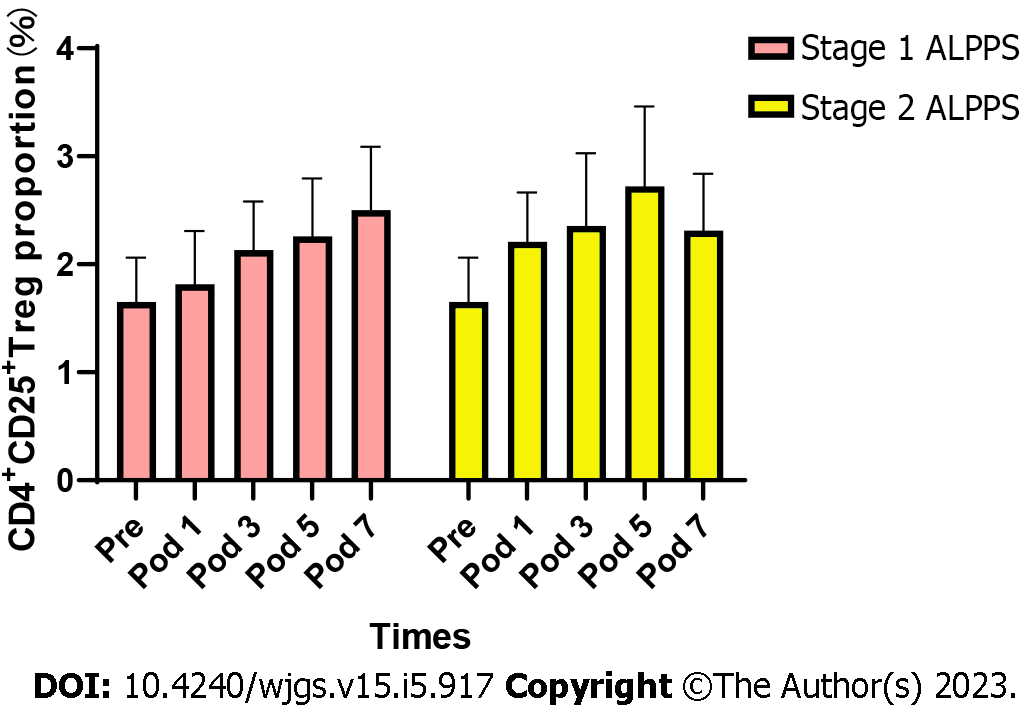

The results of flow cytometry showed that the proportion of CD4+CD25+ Tregs showed a progressive increase in the postoperative period in stage 1 and stage 2 ALPPS (Figure 1). After repeated measures ANOVA, the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) on days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 after stage 1 and stage 2 ALPPS compared to preoperatively (Table 3). The difference was statistically significant (F = 6.962, P < 0.001) when comparing the trend of CD4+CD25+ Treg percentage preoperatively and postoperatively in stage 1 ALPPS and was statistically significant (F = 4.726, P = 0.011) when comparing the trend of CD4+CD25+ Treg percentage preoperatively and postoperatively in stage 2 ALPPS.

| ALPPS | PRE | POD1 | POD3 | POD5 | POD7 | POD10 | F | P value |

| ALPPS-1 | 1.69 ± 1.32 | 1.79 ± 1.42 | 2.29 ± 1.34 | 2.41 ± 1.49 | 2.62 ± 1.72 | 2.64 ± 1.64 | 6.962 | 0.001 |

| ALPPS-2 | 1.69 ± 1.32 | 2.19 ± 1.26 | 2.28 ± 1.63 | 2.73 ± 2.05 | 2.21 ± 1.49 | 2.34 ± 1.35 | 4.726 | 0.011 |

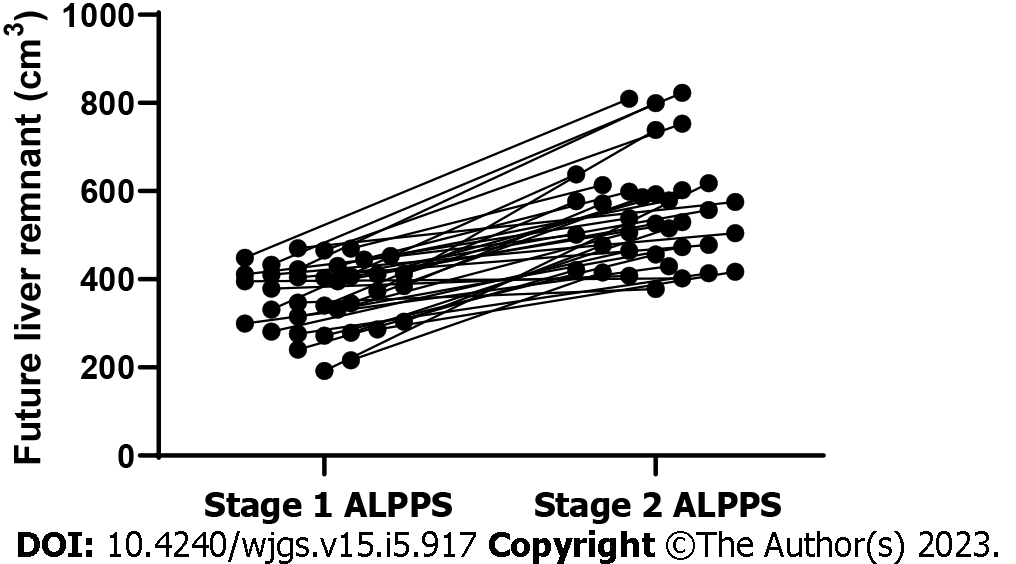

The median increase in FLR volume between stage 1 ALPPS and stage 2 ALPPS stages was 64.5% (22.3%-221.9%). The absolute and relative KGR of the FLR were 17.4 cm3/d (range = 0.45-36.6 cm3/d) and 5.0%/d (range = 0.1%-18.5%/d), respectively. The FLR volume in stage 2 ALPPS was significantly greater than the FLR volume in stage 1 ALPPS, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) (Figure 2 and Table 4).

| Variable | ALPPS stage 1 and 2 |

| SLV, cm3 | 1034.0 (851.9-1300.7) |

| Preoperation of ALPPS-1 | |

| FLR, cm3 | 1043.3 (851.8-1358.2) |

| FLR/SLV, % | 35.1 (18.9-47.4) |

| Preoperation of ALPPS-2 | |

| FLR, cm3 | 548.4 (378.1-823.0) |

| FLR/SLV, % | 53.2 (33.8-78.3) |

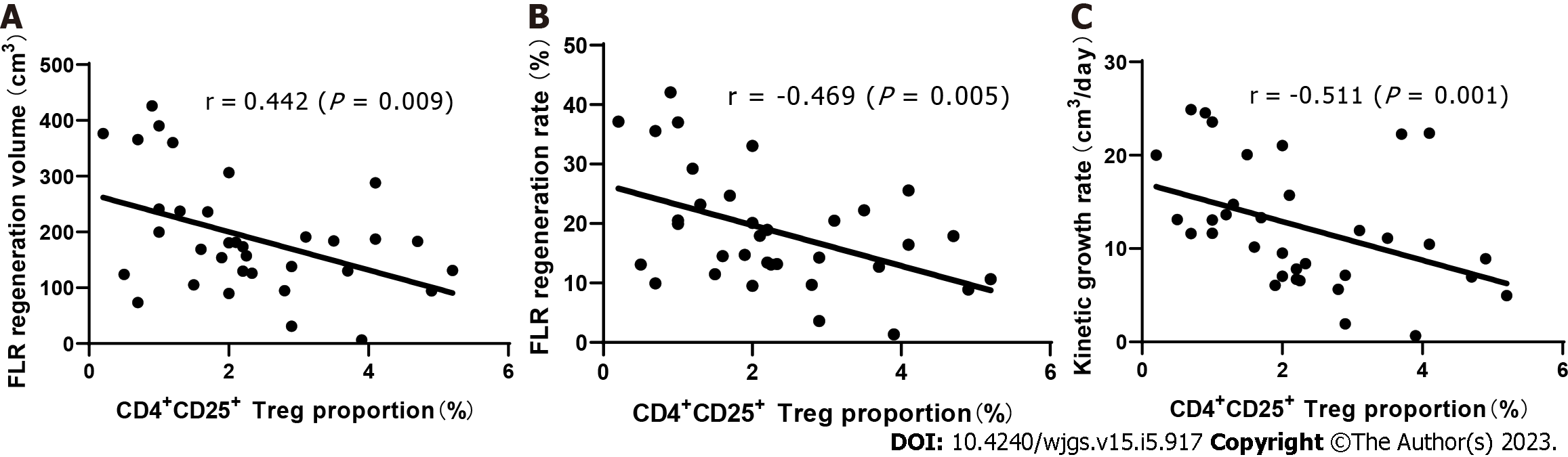

Through Spearman’s rank correlation analysis, we found that on the 3rd day after stage 1 ALPPS, the proportion of CD4+CD25+ Tregs was significantly negatively correlated with liver regeneration. The correlation coefficient between the proportion of Tregs and the hyperplasia volume between stage 1 and 2 ALPPS was r = -0.442 (P = 0.009), that between the proportion of Tregs and the hyperplasia rate was r = -0.469 (P = 0.005), and that between the proportion of Tregs and KGR was r = -0.511 (P = 0.001) (Figure 3).

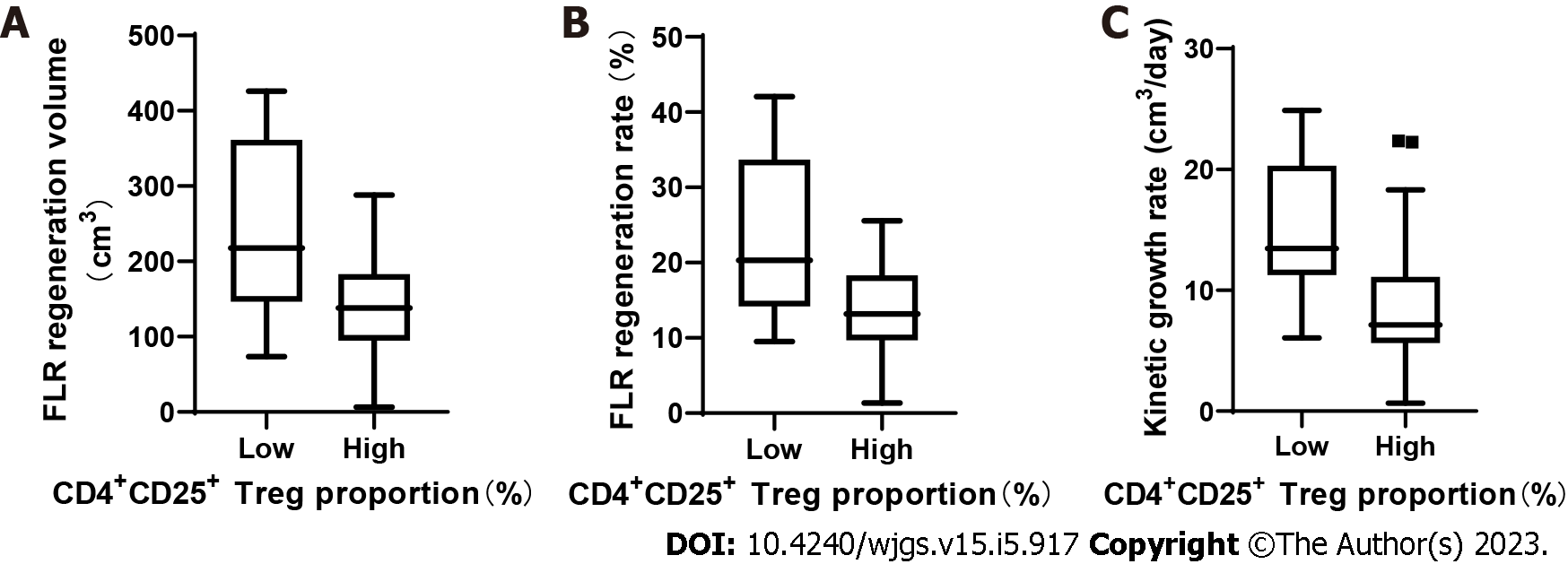

The proportion of CD4+CD25+ Tregs on the 3rd day after stage 1 ALPPS was categorized as high or low according to the median. The median KGR of patients with low and high Treg proportions was 13.3 (6.1-24.9 cm3/d) and 7.5 (0.67-22.35 cm3/d), respectively. The results showed that the proliferation volume, proliferation rate, and KGR were significantly higher in patients with low Treg proportion than in those with a high Treg proportion (P < 0.05; Figure 4).

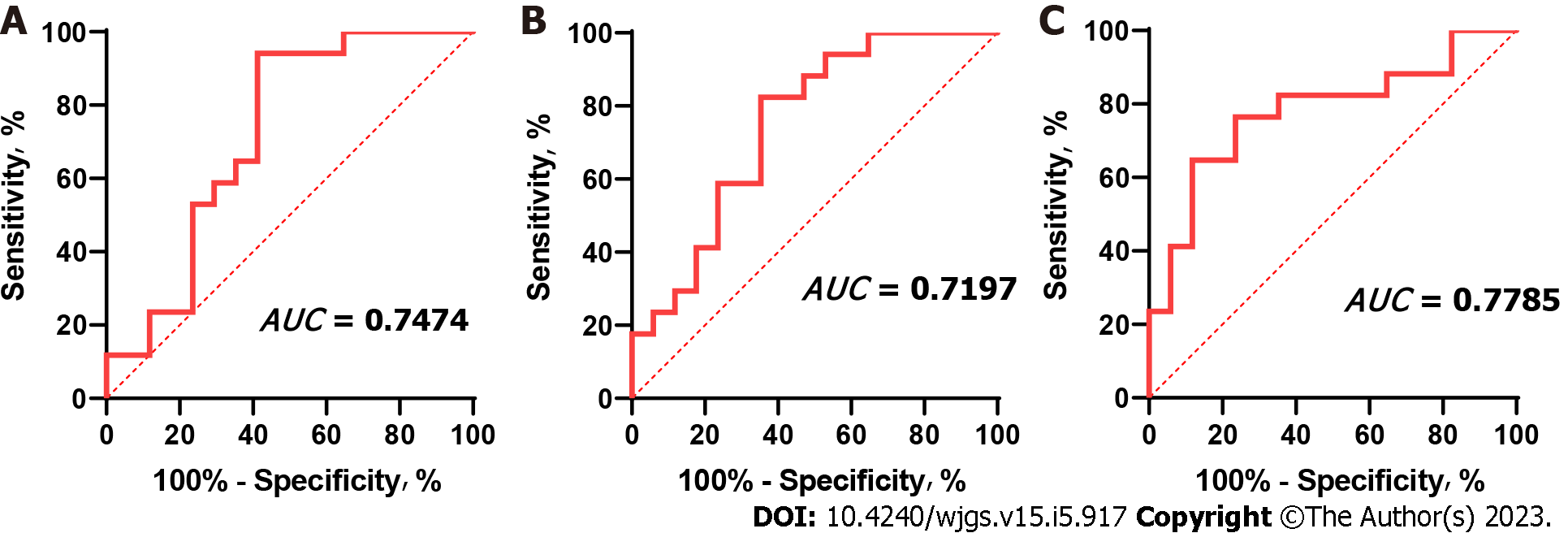

The ROC method was used to verify the accuracy of the CD4+CD25+ Treg percentage in predicting FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS. The results showed that the area under the curve (AUC) between postoperative CD4+CD25+ Treg percentage and proliferation was 0.7197 (0.5400-0.8994; P = 0.029), the AUC between CD4+CD25+ Treg percentage and proliferation rate was 0.7474 (0.5806-0.9142; P = 0.014), and the area under the ROC curve with KGR was 0.7785 (0.6172-0.9399; P = 0.006) (Figure 5).

To analyze the relationship between the preoperative proportion of CD4+CD25+ Tregs in peripheral blood and postoperative pathological liver fibrosis, we divided the preoperative CD4+CD25+ Treg results into high- and low-Treg proportion groups according to the median. The degree of pathological liver fibrosis was significantly higher in patients with a high Treg proportion than in patients with a low Treg proportion, and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.043).

The liver is considered an “immune” organ, housing a variety of resident immune cells that play a key role in maintaining organ homeostasis[18]. Resident innate immune cells consisting of macrophages or Kupffer cells, natural killer cells, natural killer T cells, and dendritic cells are considered to be the primary sentinels in the liver[19]. Tregs are a subset of T lymphocytes that regulate the immune response by suppressing the proliferation of effector T lymphocytes and the production of cytokines[20]. In 2003, the forkhead box transcription factor FOXP3 was identified as a specific marker for Tregs and its expression is thought to be essential for their suppressive activity[21]. Tregs arise from the thymus and constitutively express high levels of interleukin (IL)-2 receptor alpha chain, cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated antigen-4, and glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor. Tregs account for 5% to 10% of peripheral CD4+ T cells[22]. Early studies have demonstrated that the suppressive effect of Tregs in vivo is mainly achieved through the production of suppressive cytokines such as IL-10, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, and IL-35[23]. Recent studies have demonstrated that immunosuppressive CD4+CD25+ Tregs represent a unique T cell lineage that is functionally and developmentally distinct from other T cells, with CD4+CD25+ Tregs involved in regulating the immune response/immune tolerance in an “active” manner. Their main function is to suppress the function of self-reactive T cells and multiple immune cells, inhibit the proliferation of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, perform immune homeostatic functions, and maintain immune tolerance and immune homeostasis[24].

The role of Tregs in tissue and organ repair and regeneration has received much attention in recent years[25]. Burzyn et al[26] showed that Treg populations with different phenotypes and functions rapidly accumulate during acute injury in mouse skeletal muscle, changing from a pro-inflammatory to a pro-regenerative state. Preferential induction of Tregs with hyperexcitable anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody increases Treg infiltration into the myocardium after myocardial infarction. Higher numbers of Tregs promote macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype in the healing myocardium and reduce ventricular rupture, leading to improved myocardial survival[27]. Tiemessen et al[28] found that secretion of IL-10, IL-4, and IL-13 by Tregs induce the polarization of M1 pro-inflammatory macrophages into M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages, which promotes the proliferation and differentiation of muscle satellite cells and secretes chemokines to promote muscle regeneration. Depletion of Tregs after treatment of FOXP3DTR mice with diphtheria toxin after skin injury resulted in significantly reduced wound closure with increased tissue granulation and superficial scabbing, indicating that Tregs promote skin wound healing[29]. Epithelial cell proliferation during lung recovery was found to be significantly impaired after specific elimination of Tregs from FOXP3DTR mice treated with diphtheria toxin in an acute lung injury or partial lung resection model[30]. Shi et al[31] found that Treg-derived bone bridge proteins act through integrin receptors on microglia to enhance the repair activity of microglia, thereby promoting oligodendrocyte production and white matter repair. IL-33 has been found to promote the recruitment of Tregs in damaged tissues and facilitate recovery after central nervous system (CNS) injury. In addition, mice lacking IL-33 had impaired recovery after CNS injury, which was associated with reduced infiltration of myeloid cells at the site of injury and reduced induction of M2 homologous genes[32].

As the liver is a regenerative organ, the mechanism of regeneration of the FLR after liver cancer surgery is of great interest. FLR volume is an important limiting factor in the safe performance of hepatectomy[4]. For giant HCC with a small FLR volume, resection rates can be improved by compensatory augmentation of the FLR. Reported by German surgeon Schnitzbauer et al[8] and summarized and named in 2012 as an innovative hepatectomy – ALPPS. When the volume of the FLR after stage 1 ALPPS meets safety criteria, a second-stage resection can be performed, which creates the opportunity for radical resection of the tumor in some patients with liver cancer who cannot undergo direct hepatectomy. Preoperative assessment and screening is particularly important prior to treatment with ALPPS, which has more stringent screening criteria. These include preoperative liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, tumor staging and grading, and most critically, accurate assessment of liver reserve. For accurate preoperative assessment of liver reserve there are several methods to assess safety after hepatectomy, such as the Child-Pugh score of liver function, measurement of indocyanine green retention test, and preoperative estimation of postoperative liver remnants by a three-dimensional imaging system[33,34]. In some patients with rigorously screened liver cancer, these risks are consistent with conventional hepatectomy and increase the rate of resection for giant liver cancer[35]. The results of our team’s study on ALPPS in patients with isolated giant HCC that cannot be resected in one stage suggest that ALPPS is a viable treatment option for patients with HCC that cannot be resected in one stage[16].

In the development of ALPPS, numerous studies have confirmed that the regenerative effect of ALPPS is significantly better than that of PVL[36,37]. The majority of patients undergoing ALPPS in Europe and the United States have metastatic liver cancer without a background of cirrhosis, unlike patients undergoing ALPPS in China, where the majority of patients have primary liver cancer and approximately 85% have post-hepatitis cirrhosis[38]. After these patients have undergone stage 1 ALPPS, 30%-40% of them still have FLR dysplasia, resulting in delayed planned stage 2 surgery or the inability to undergo a radical stage 2 resection. The mechanisms involved in the promotion of FLR regeneration by ALPPS have been the focus of research, but the exact mechanisms have not been elucidated. The possible mechanisms are now thought to be twofold: (1) After PVL of the liver, the portal blood flow in the FLR increases and the portal pressure rises, promoting rapid proliferation of the FLR; and (2) PVL of the liver on the tumor side leads to an ischemic state of the tumor, which in combination with the separation of the liver parenchyma, releases a large amount of inflammatory factors or complement that may also be associated with rapid proliferation of the liver[39,40]. Tregs, as emerging regeneration-associated target cells, have never been reported in studies of liver regeneration. Therefore, we offer speculation on how Tregs might affect FLR regeneration after ALPPS and explore the role of CD4+CD25+ Tregs in ALPPS-associated FLR regeneration and the regenerative mechanisms involved.

Flow cytometry was used to detect changes in the proportion of CD4+CD25+ Tregs to CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood of patients after stage 1 ALPPS and to correlate with indicators of residual postoperative liver regeneration. The results showed that the CD4+CD25+ Treg proportion showed a gradual increase after stage 1 ALPPS, and in addition the CD4+CD25+ Treg proportion after stage 1 ALPPS showed a significant negative correlation with the FLR regeneration indicators (proliferation volume, proliferation rate, and KGR). This suggests that Tregs may inhibit the regeneration of the FLR after ALPPS in patients with liver cancer. To verify the reliability of the results of the relationship between peripheral blood Tregs and FLR regeneration, we performed ROC analysis, which showed that the area under the ROC curve between Treg percentage and proliferation volume and proliferation rate and KGR were > 0.70 (P < 0.05), indicating that Treg percentage is highly accurate in predicting FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS.

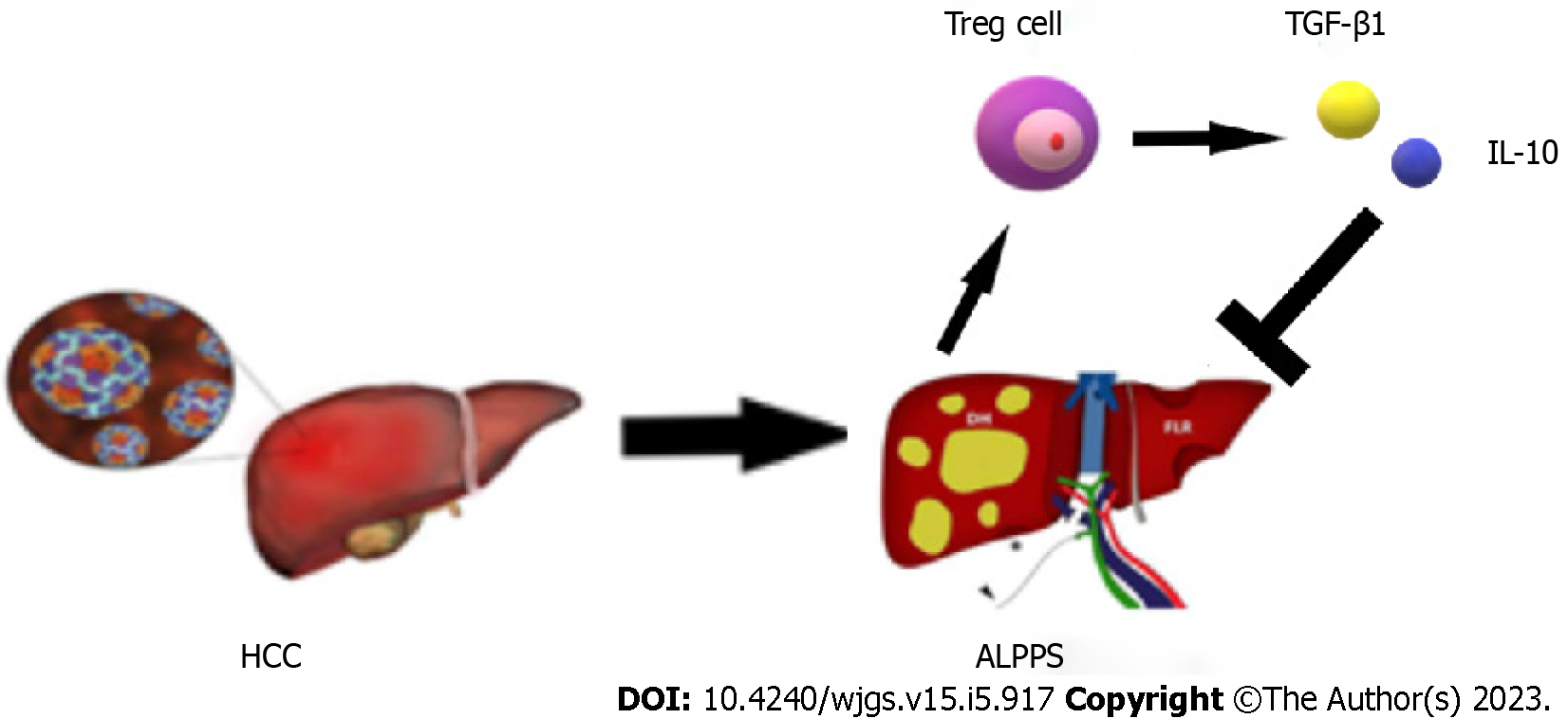

During the recovery period after stage 1 ALPPS, the body’s immune function is disrupted for a short period of time due to the high surgical trauma, and immune homeostasis is disrupted, causing Tregs to be elevated to some extent. The high expression of Tregs suggests the establishment of immune tolerance and the high secretion of the suppressive cytokines TGF-β1 and IL-10, which significantly inhibit the development of the inflammatory response. Imbalance in the tumor microenvironment, which disrupts the regenerative microenvironmental homeostasis of the FLR, ultimately leading to poor regeneration of the FLR after surgery (Figure 6). The presence of tumor cells can induce rapid and sustained proliferation of Tregs, a process that may be interrupted immediately when the tumor is removed and lead to a significant reduction in the expression of tumor-associated Tregs in peripheral blood in the early postoperative period[41]. About 1 wk after radical resection of the tumor, sustained organismal stress effects may lead to the upregulation of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Treg expression in peripheral blood. This finding was validated in the present study, where Treg numbers continued to show an increasing trend in the first 4 d postoperatively and began to show a decrease on postoperative day 5 after resection of stage 2 ALPPS stage liver tumors.

It has been reported that the number of CD4+CD25+ Tregs detected in peripheral blood, localized tumor, tumor-infiltrating lymph nodes, and draining lymph nodes of patients with HCC tumors is negatively correlated with disease progression and prognosis[42]. Increased numbers of Tregs in peripheral blood may be associated with impaired immune response, high mortality, and shortened survival in patients with liver cancer[43]. In this study, we divided the postoperative CD4+CD25+ Tregs into two groups: high and low. By comparing the results between the two groups, we showed that the patients with a low Treg percentage had a statistically significant higher KGR than those with a high Treg percentage (P = 0.006). The patients with a high Treg percentage had a statistically significant higher degree of postoperative pathological liver fibrosis than those with a low Treg percentage (P = 0.043). There are many factors affecting poor FLR regeneration such as hepatic arteriovenous-portal fistula, portal hyperperfusion, and liver fibrosis. Our group’s latest clinical study reported that hepatic arteriovenous-portal fistulas after stage 1 ALPPS resulted in poor regeneration of the FLR[44]. Huang et al[45] analyzed patients with massive HCC in a post-hepatitis B cirrhotic background and showed that the FLR could still proliferate after ALPPS in patients with severe liver fibrosis, but less efficiently than in patients with mild to moderate liver fibrosis. In Chia et al[46], it was shown that liver fibrosis negatively affects the growth of the FLR after ALPPS. The results of this study showed that patients with a higher percentage of Tregs in their peripheral blood had more severe liver fibrosis. In this case, the rate of regeneration of the FLR after stage 1 ALPPS is reduced and the regeneration of the FLR is limited. Therefore, Tregs may be one of the factors affecting the regeneration of the FLR after stage 1 ALPPS.

Advances and developments in ALPPS technology have made radical treatment available for HCC with small FLR volumes, but HCC with insufficient FLR is mostly intermediate and advanced and is also often associated with adverse factors affecting liver regeneration such as hepatitis B cirrhosis, and still leaves a proportion of patients unable to meet the demand for ALPPS surgery. In the present study, we found that Tregs, as immune-negative regulatory cells, played a role in the postoperative FLRs of liver cancer patients who underwent ALPPS surgery, as well as in the postoperative FLRs of the rat ALPPS model, potentially inhibiting the regeneration of the FLRs. In short, attenuating or knocking down Tregs in the tumor microenvironment of HCC after effective Treg immunotherapy following stage 1 ALPPS may promote regeneration of the FLR. For example, Beyer et al[47] found that fludarabine treatment resulted in a significant reduction in Treg numbers and a concomitant reduction in function, and that fludarabine also promoted apoptosis of Tregs. Dannull et al[48] found that IL-2 diphtheria toxin coupling significantly reduced the amount of Tregs present in the peripheral blood of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and eliminated Treg-mediated immunosuppressive activity in vivo, enabling effective antitumor immunity with therapeutic impact by combining Treg depletion strategies. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore drugs that target the abnormal increase in Tregs after HCC surgery to increase the rate of regeneration of the FLR after ALPPS, reduce the waiting time between ALPPS surgeries in patients and improve the quality of life of HCC patients.

CD4+CD25+ Tregs in the peripheral blood of patients with massive HCC at stage 1 ALPPS were negatively correlated with indicators of FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS and may influence the degree of fibrosis in patients’ livers. Treg percentage was highly accurate in predicting the FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS.

The mechanism of regeneration of the future liver remnant (FLR) after associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) is a hot research topic in the field of hepatobiliary surgery, but the definitive mechanism of regeneration has not yet been fully elucidated.

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are closely associated with tissue and organ regeneration in a number of studies, but no studies have been reported on their association with liver regeneration.

This study explored the correlation between CD4+CD25+ Tregs and FLR regeneration after ALPPS from the perspectives of FLR regeneration volume, FLR regeneration rate, kinetic growth rate (KGR), and liver fibrosis score.

Collection of clinical data and peripheral blood samples from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients treated with ALPPS. Flow cytometry was performed to detect changes in the proportion of CD4+CD25+ Tregs to CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood before and after ALPPS. To analyze the relationship between peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ Treg proportion and clinicopathological information and FLR.

The postoperative CD4+CD25+ Treg proportion in stage 1 ALPPS was negatively correlated with the amount of proliferation volume, proliferation rate, and KGR of the FLR after stage 1 ALPPS. Patients with a high Treg proportion had a lower postoperative KGR as well as a more severe degree of fibrosis. Also, Treg proportion was a good predictor of in postoperative proliferation volume, proliferation rate and KGR.

CD4+CD25+ Tregs in the peripheral blood of patients with HCC at stage 1 ALPPS were negatively correlated with indicators of FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS and may influence the degree of fibrosis in patients’ livers. Treg percentage was highly accurate in predicting the FLR regeneration after stage 1 ALPPS.

Research on the mechanism of FLR regeneration after ALPPS is still being explored. In future studies, this report provides certain strong evidence to explore the regeneration mechanism, which will provide positive reference value to further improve the regeneration rate of FLR after ALPPS, reduce the waiting time of patients for ALPPS surgery and improve the survival rate of HCC patients.

The authors would like to thank Zong-Rui Jin, Guo-Lin Wu, Jue Wang, Qi-Ling Yi, Zhu-Jing Lan, and Ke-Yu Huang for their help in the perioperative management of patients and collection of clinical data and specimens.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hori T, Japan; Rather AA, India S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64661] [Article Influence: 16165.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (176)] |

| 2. | Bruix J, Takayama T, Mazzaferro V, Chau GY, Yang J, Kudo M, Cai J, Poon RT, Han KH, Tak WY, Lee HC, Song T, Roayaie S, Bolondi L, Lee KS, Makuuchi M, Souza F, Berre MA, Meinhardt G, Llovet JM; STORM investigators. Adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection or ablation (STORM): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1344-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 558] [Cited by in RCA: 788] [Article Influence: 78.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang Y, Zhang L, Ning J, Zhang X, Li X, Chen G, Zhao X, Wang X, Yang S, Yuan C, Dong J, Chen H. Preoperative Remnant Liver Function Evaluation Using a Routine Clinical Dynamic Gd-EOB-DTPA-Enhanced MRI Protocol in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:3672-3682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nakamura N, Hatano E, Iguchi K, Seo S, Taura K, Uemoto S. Posthepatectomy Liver Failure Affects Long-Term Function After Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. World J Surg. 2016;40:929-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Knoefel WT, Gabor I, Rehders A, Alexander A, Krausch M, Schulte am Esch J, Fürst G, Topp SA. In situ liver transection with portal vein ligation for rapid growth of the future liver remnant in two-stage liver resection. Br J Surg. 2013;100:388-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | de Martel C, Maucort-Boulch D, Plummer M, Franceschi S. World-wide relative contribution of hepatitis B and C viruses in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;62:1190-1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Loffroy R, Favelier S, Chevallier O, Estivalet L, Genson PY, Pottecher P, Gehin S, Krausé D, Cercueil JP. Preoperative portal vein embolization in liver cancer: indications, techniques and outcomes. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2015;5:730-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schnitzbauer AA, Lang SA, Goessmann H, Nadalin S, Baumgart J, Farkas SA, Fichtner-Feigl S, Lorf T, Goralcyk A, Hörbelt R, Kroemer A, Loss M, Rümmele P, Scherer MN, Padberg W, Königsrainer A, Lang H, Obed A, Schlitt HJ. Right portal vein ligation combined with in situ splitting induces rapid left lateral liver lobe hypertrophy enabling 2-staged extended right hepatic resection in small-for-size settings. Ann Surg. 2012;255:405-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 837] [Cited by in RCA: 934] [Article Influence: 71.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mills KH. Regulatory T cells: friend or foe in immunity to infection? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:841-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 488] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Asano M, Toda M, Sakaguchi N, Sakaguchi S. Autoimmune disease as a consequence of developmental abnormality of a T cell subpopulation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:387-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 976] [Cited by in RCA: 980] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zheng MH, Gu DN, Braddock M, Leishman AJ, Jin C, Wen JS, Gong YW, Chen YP. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells: a therapeutic target for liver diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:313-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Peng G, Li S, Wu W, Sun Z, Chen Y, Chen Z. Circulating CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells correlate with chronic hepatitis B infection. Immunology. 2008;123:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rushbrook SM, Ward SM, Unitt E, Vowler SL, Lucas M, Klenerman P, Alexander GJ. Regulatory T cells suppress in vitro proliferation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during persistent hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:7852-7859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Muñoz-Rojas AR, Mathis D. Tissue regulatory T cells: regulatory chameleons. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:597-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fu-Gui L, Lu-Nan Y, Bo L, Yong Z, Tian-Fu W, Ming-Qing X, Wen-Tao W, Zhe-Yu C. Estimation of standard liver volume in Chinese adult living donors. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:4052-4056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Deng Z, Jin Z, Qin Y, Wei M, Wang J, Lu T, Zhang L, Zeng J, Bao L, Guo Y, Peng M, Xu B, Wen Z. Efficacy of the association liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy for the treatment of solitary huge hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective single-center study. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Oldhafer KJ, Stavrou GA, van Gulik TM; Core Group. ALPPS--Where Do We Stand, Where Do We Go?: Eight Recommendations From the First International Expert Meeting. Ann Surg. 2016;263:839-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ficht X, Iannacone M. Immune surveillance of the liver by T cells. Sci Immunol. 2020;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lian M, Selmi C, Gershwin ME, Ma X. Myeloid Cells and Chronic Liver Disease: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:307-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ng WF, Duggan PJ, Ponchel F, Matarese G, Lombardi G, Edwards AD, Isaacs JD, Lechler RI. Human CD4(+)CD25(+) cells: a naturally occurring population of regulatory T cells. Blood. 2001;98:2736-2744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5576] [Cited by in RCA: 5862] [Article Influence: 266.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Takahashi T, Ishida Y, Sakaguchi S. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:135-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1294] [Cited by in RCA: 1293] [Article Influence: 56.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen X, Du Y, Lin X, Qian Y, Zhou T, Huang Z. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in tumor immunity. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;34:244-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yi H, Zhen Y, Jiang L, Zheng J, Zhao Y. The phenotypic characterization of naturally occurring regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2006;3:189-195. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Li J, Tan J, Martino MM, Lui KO. Regulatory T-Cells: Potential Regulator of Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Front Immunol. 2018;9:585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Burzyn D, Kuswanto W, Kolodin D, Shadrach JL, Cerletti M, Jang Y, Sefik E, Tan TG, Wagers AJ, Benoist C, Mathis D. A special population of regulatory T cells potentiates muscle repair. Cell. 2013;155:1282-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 736] [Cited by in RCA: 947] [Article Influence: 86.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Weirather J, Hofmann UD, Beyersdorf N, Ramos GC, Vogel B, Frey A, Ertl G, Kerkau T, Frantz S. Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells improve healing after myocardial infarction by modulating monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Circ Res. 2014;115:55-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 616] [Article Influence: 56.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tiemessen MM, Jagger AL, Evans HG, van Herwijnen MJ, John S, Taams LS. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce alternative activation of human monocytes/macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19446-19451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 694] [Cited by in RCA: 671] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nosbaum A, Prevel N, Truong HA, Mehta P, Ettinger M, Scharschmidt TC, Ali NH, Pauli ML, Abbas AK, Rosenblum MD. Cutting Edge: Regulatory T Cells Facilitate Cutaneous Wound Healing. J Immunol. 2016;196:2010-2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mock JR, Garibaldi BT, Aggarwal NR, Jenkins J, Limjunyawong N, Singer BD, Chau E, Rabold R, Files DC, Sidhaye V, Mitzner W, Wagner EM, King LS, D'Alessio FR. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells promote lung epithelial proliferation. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:1440-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shi L, Sun Z, Su W, Xu F, Xie D, Zhang Q, Dai X, Iyer K, Hitchens TK, Foley LM, Li S, Stolz DB, Chen K, Ding Y, Thomson AW, Leak RK, Chen J, Hu X. Treg cell-derived osteopontin promotes microglia-mediated white matter repair after ischemic stroke. Immunity. 2021;54:1527-1542.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gadani SP, Walsh JT, Smirnov I, Zheng J, Kipnis J. The glia-derived alarmin IL-33 orchestrates the immune response and promotes recovery following CNS injury. Neuron. 2015;85:703-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | D'Haese JG, Neumann J, Weniger M, Pratschke S, Björnsson B, Ardiles V, Chapman W, Hernandez-Alejandro R, Soubrane O, Robles-Campos R, Stojanovic M, Dalla Valle R, Chan AC, Coenen M, Guba M, Werner J, Schadde E, Angele MK. Should ALPPS be Used for Liver Resection in Intermediate-Stage HCC? Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1335-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yokoi H, Isaji S, Yamagiwa K, Tabata M, Sakurai H, Usui M, Mizuno S, Uemoto S. Donor outcome and liver regeneration after right-lobe graft donation. Transpl Int. 2005;18:915-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Linecker M, Björnsson B, Stavrou GA, Oldhafer KJ, Lurje G, Neumann U, Adam R, Pruvot FR, Topp SA, Li J, Capobianco I, Nadalin S, Machado MA, Voskanyan S, Balci D, Hernandez-Alejandro R, Alvarez FA, De Santibañes E, Robles-Campos R, Malagó M, de Oliveira ML, Lesurtel M, Clavien PA, Petrowsky H. Risk Adjustment in ALPPS Is Associated With a Dramatic Decrease in Early Mortality and Morbidity. Ann Surg. 2017;266:779-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lang H, de Santibañes E, Schlitt HJ, Malagó M, van Gulik T, Machado MA, Jovine E, Heinrich S, Ettorre GM, Chan A, Hernandez-Alejandro R, Robles Campos R, Sandström P, Linecker M, Clavien PA. 10th Anniversary of ALPPS-Lessons Learned and quo Vadis. Ann Surg. 2019;269:114-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Moris D, Ronnekleiv-Kelly S, Kostakis ID, Tsilimigras DI, Beal EW, Papalampros A, Dimitroulis D, Felekouras E, Pawlik TM. Operative Results and Oncologic Outcomes of Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy (ALPPS) Versus Two-Stage Hepatectomy (TSH) in Patients with Unresectable Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Surg. 2018;42:806-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zheng RS, Zhang S, Zeng HM, Wang SM, Sun KX, Chen R, Li L, Wei WQ, He J. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2016. J National Cancer Center. 2022;2:1-9. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 852] [Cited by in RCA: 951] [Article Influence: 317.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Yang X, Yang C, Qiu Y, Shen S, Kong J, Wang W. A preliminary study of associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy in a rat model of liver cirrhosis. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18:1203-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Schlegel A, Lesurtel M, Melloul E, Limani P, Tschuor C, Graf R, Humar B, Clavien PA. ALPPS: from human to mice highlighting accelerated and novel mechanisms of liver regeneration. Ann Surg. 2014;260:839-46; discussion 846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Peng L, Kjaergäard J, Plautz GE, Awad M, Drazba JA, Shu S, Cohen PA. Tumor-induced L-selectinhigh suppressor T cells mediate potent effector T cell blockade and cause failure of otherwise curative adoptive immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2002;169:4811-4821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Liu JY, Zhang XS, Ding Y, Peng RQ, Cheng X, Zhang NH, Xia JC, Zeng YX. The changes of CD4+CD25+/CD4+ proportion in spleen of tumor-bearing BALB/c mice. J Transl Med. 2005;3:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Fu J, Xu D, Liu Z, Shi M, Zhao P, Fu B, Zhang Z, Yang H, Zhang H, Zhou C, Yao J, Jin L, Wang H, Yang Y, Fu YX, Wang FS. Increased regulatory T cells correlate with CD8 T-cell impairment and poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2328-2339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 692] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ye C, Zhang L, Xu B, Li J, Lu T, Zeng J, Guo Y, Peng M, Bao L, Wen Z, Wang J. Hepatic Arterioportal Fistula Is Associated with Decreased Future Liver Remnant Regeneration after Stage-I ALPPS for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25:2280-2288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Huang PB, Hu ZG, Xv QD, Yan YC, Wang J. [Application of ALPPS in massive hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatitis B cirrhosis]. Lingnan Modern Clin Sur. 2015;5:527-532. |

| 46. | Chia DKA, Yeo Z, Loh SEK, Iyer SG, Madhavan K, Kow AWC. ALPPS for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is Associated with Decreased Liver Remnant Growth. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:973-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Beyer M, Kochanek M, Darabi K, Popov A, Jensen M, Endl E, Knolle PA, Thomas RK, von Bergwelt-Baildon M, Debey S, Hallek M, Schultze JL. Reduced frequencies and suppressive function of CD4+CD25hi regulatory T cells in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia after therapy with fludarabine. Blood. 2005;106:2018-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Dannull J, Su Z, Rizzieri D, Yang BK, Coleman D, Yancey D, Zhang A, Dahm P, Chao N, Gilboa E, Vieweg J. Enhancement of vaccine-mediated antitumor immunity in cancer patients after depletion of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3623-3633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 776] [Cited by in RCA: 726] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |