Published online Apr 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i4.723

Peer-review started: October 19, 2022

First decision: January 3, 2023

Revised: January 20, 2023

Accepted: March 8, 2023

Article in press: March 8, 2023

Published online: April 27, 2023

Processing time: 185 Days and 16.3 Hours

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is a common and potentially life-threatening clinical event. To date, the literature on the long-term global epidemiology of GIB has not been systematically reviewed.

To systematically review the published literature on the worldwide epidemiology of upper and lower GIB.

EMBASE® and MEDLINE were queried from 01 January 1965 to September 17, 2019 to identify population-based studies reporting incidence, mortality, or case-fatality rates of upper GIB (UGIB) or lower GIB (LGIB) in the general adult population, worldwide. Relevant outcome data were extracted and summarized (including data on rebleeding following initial occurrence of GIB when available). All included studies were assessed for risk of bias based upon reporting guidelines.

Of 4203 retrieved database hits, 41 studies were included, comprising a total of around 4.1 million patients with GIB worldwide from 1980–2012. Thirty-three studies reported rates for UGIB, four for LGIB, and four presented data on both. Incidence rates ranged from 15.0 to 172.0/100000 person-years for UGIB, and from 20.5 to 87.0/100000 person-years for LGIB. Thirteen studies reported on temporal trends, generally showing an overall decline in UGIB incidence over time, although a slight increase between 2003 and 2005 followed by a decline was shown in 5/13 studies. GIB-related mortality data were available from six studies for UGIB, with rates ranging from 0.9 to 9.8/100000 person-years, and from three studies for LGIB, with rates ranging from 0.8 to 3.5/100000 person-years. Case-fatality rate ranged from 0.7% to 4.8% for UGIB and 0.5% to 8.0% for LGIB. Rates of rebleeding ranged from 7.3% to 32.5% for UGIB and from 6.7% to 13.5% for LGIB. Two main areas of potential bias were the differences in the operational GIB definition used and inadequate information on how missing data were handled.

Wide variation was seen in estimates of GIB epidemiology, likely due to high heterogeneity between studies however, UGIB showed a decreasing trend over the years. Epidemiological data were more widely available for UGIB than for LGIB.

Core Tip: This review addresses an important literature gap in summarizing the long-term global epidemiology of GIB. Epidemiological data were more widely available for UGIB than for LGIB, which were limited. Estimates of GIB were highly heterogeneous, often due to differences in case definitions, but showed a decreasing trend for UGIB incidence.

- Citation: Saydam ŞS, Molnar M, Vora P. The global epidemiology of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding in general population: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(4): 723-739

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i4/723.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i4.723

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is a potentially life-threatening clinical event resulting in more than 400000 hospital admissions in the United States (US) each year, and associated with substantial economic burden for healthcare systems[1,2]. Upper GIB (UGIB) is observed between the mouth and the duodenum, while lower GIB (LGIB) occurs distal to the ligament of Treitz[3,4]. Risk factors for GIB are well-established and include older age, being male, smoking, alcohol use, and medication use[5-13]. Previous reviews on the epidemiology of UGIB have focused on specific etiologies such as peptic ulcer bleeding (PUB)[11,14,15], outcomes associated with risk factors[16-18], or prediction scores[19-21], while reviews on LGIB are lacking. An overarching review of the long-term worldwide epidemiology of GIB would enable the totality of evidence on this topic to be obtained, covering decades that have seen advances in preventative measures and management. This would also help identify areas where data gaps remain, guiding future investigations. We therefore performed a systematic review of the literature with the aim of describing the long-term worldwide epidemiology of UGIB and LGIB in the general population.

EMBASE® and MEDLINE databases were queried from 01 January 1965 to September 17, 2019, using searches for the keywords ‘epidemiology’, ‘incidence’, ‘prevalence’, ‘mortality’, ‘case fatality’ combined with ‘gastrointestinal’, ‘hemorrhage’, ‘haemorrhage’, ‘bleeding’ in title or abstract. The search was restricted to studies in humans and those written in English. Deduplication across databases was performed by the embedded function within EMBASE® platform. The complete electronic search strategy is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Following Cochrane Collaboration guidelines[3,4], we included population-based studies reporting either incidence, mortality or case-fatality rates for UGIB and/or LGIB in the general adult population. We included studies on either acute or chronic GIB, and those on variceal or non-variceal UGIB (NVUGIB). We excluded randomized controlled trials and interventional studies because they are not designed to assess epidemiology of a disease and are based on selected groups of individuals. Conference abstracts, editorials, letters, notes, and short surveys were excluded. Studies among patient subgroups (e.g., cirrhotic patients, drug users), and those that investigated only specific GIB etiologies (e.g., PUB, Mallory-Weiss) or degrees of bleeding (e.g., massive LGIB) were also excluded, as were those where GIB was undefined, unspecified as UGIB/LGIB, or where mortality rates were not specified as being GIB-related. When two or more publications presented data from the same or overlapping population, we included only the study conducted over the most recent period, unless the older data provided more extensive information on study endpoints.

Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors (ŞSS and MM), with disagreements resolved by cross-checks and discussions with the third author (PV). For remaining articles, full-text was reviewed. Details about the study design, population and results were extracted from each article. When rates were not reported explicitly, they were calculated from the available data (including from graphical displays) wherever possible.

Data were presented for UGIB and LGIB separately. Outcome measures were incidence rate, mortality rate and case-fatality rate. Incidence rates were extracted or calculated and presented as the number of patients with GIB divided by person-time, and mortality rates were extracted or calculated as the number of GIB-related deaths divided by person-time; both were expressed per 100000 person-years. For estimate calculations, person-time was defined as the population size of the catchment area multiplied by follow-up time (usually approximated as the study duration). Case-fatality rates were extracted or calculated as the percentage of GIB-related deaths among the total number of patients with GIB in the study population. Where available, data on rebleeding were extracted or determined as the percentage of GIB recurrences among patients with GIB. Rates were displayed using forest plots with 95% confidence intervals. Studies that reported incidence rates at different timepoints were displayed graphically to visualize temporal trends. Analyses were conducted using R on RStudio (Version 1.1.423) with ggplot2 and forest plot packages.

Risk of bias was assessed at the study level based on published guidance with amendments[22] (Supplementary Table 2). Each study was also evaluated against reporting guidelines for observational studies[23] (Supplementary Table 3). Risk of bias across all studies was not assessed as rates were presented individually for each study, and pooled cumulative estimates were not calculated.

A total of 4793 database hits were retrieved from the search (4203 from EMBASE®, 509 from MEDLINE). Following the screening of titles and abstracts (4415 were excluded), 353 articles remained. After full-text screening, 36 articles were retained for the final review[24-59]. A further five studies were included after screening bibliographies of full-text articles and relevant reviews[60-64](see PRISMA flowchart in Supplementary Figure 1 and hierarchical reason for exclusion in Supplementary Table 4). Of the 41 included studies (covering approximately 4.2 million individuals), 33 studies provided estimates on UGIB (eight specifically on NVUGIB), four on LGIB, and the remaining four reported data on both. Characteristics of the included studies are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Twenty-six studies were from Europe, eight from North America, six from Asia-Pacific and one from the Middle East. Of 33 studies on UGIB, eight reported estimates only for NVUGIB. No population-based study was identified that reported epidemiological variables of interest for variceal UGIB. The diagnostic procedure for GIB was endoscopy in 27 studies, and unclear for the remaining studies. Data sources used were hospital records (19 studies), administrative databases (12 studies), hospital surveys (7 studies), electronic health records, a survey cohort study (one study) and claims data combined with clinical data (one study).

| Ref. | Study period | Country (region) | Data source1 | Design | Clinical event |

| Schlup et al[24], 1984 | 1 September 1980 - 28 February 1982 | New Zealand (Dunedin) | Clinical data (Dunedin public hospitals) | P | UGIB |

| Katschinski et al[25], 1989 | 1 April 1984 - 31 March 1986 | UK (Nottingham) | Clinical data (The Nottingham City and University Hospitals) | P | UGIB |

| Longstreth[26], 1995 | 1991 | USA (San Diego) | Administrative claims database (KPMCP) | R | AUGIB |

| Bramley et al[27], 1996 | October 1991 - September 1993 | Scotland (Grampian and the Northern Isles) | Clinical data (Aberdeen Royal Infirmary) | P | LGIB |

| Masson et al[28], 1996 | October 1991 - September 1993 | Scotland (Orkney and Shetland) | Clinical data (Aberdeen Royal Infirmary) | P | UGIB |

| Blatchford et al[60], 1997 | September 1992 - Feb 1993 | West Scotland | Clinical data (Multicenter) | P | AUGIB |

| El Bagir et al[29], 1997 | May 1991 - May 1993 | Saudi Arabia (Abha City) | Clinical data (Asir Central Hospital) | P | AUGIB |

| Longstreth[30], 1997 | January 1990 - December 1993 | USA (San Diego) | Claims (KPMCP) | R | ALGIB |

| Soplepmann et al[61], 1997 | 1 August 1992 - 31 July 1994 | Finland (Central Finland) | Clinical data (Central Hospital of Central Finland) | P | AUGIB |

| Estonia (Tartu) | Clinical data (Tartu University Hospital) | ||||

| Vreeburg et al[31], 1997 | July 1993 - July 1994 | Netherlands (Amsterdam area) | Hospital survey (Two university and ten regional hospitals) | P | AUGIB |

| Czernichow et al[32], 2000 | 1 January - 30 June 1996 | France (Finistere, Gironde, Seine Maritime and Somme) | Hospital survey (29 public hospitals and 96 private practices) | P | AUGIB |

| Paspatis et al[33], 2000 | February 1998 - February 1999 | Greece (Heraklion, Crete) | Hospital survey | P | AUGIB |

| Tenias Burillo et al[34], 2001 | April 1995 - March 1999 | Spain (Valencia) | Clinical data (Lluis Alcanyis Hospital) | P | NVUGIB |

| Lewis et al[62], 2002 | 1992 - 1999 | USA | Hospital survey (NHDS) | R | UGIB |

| van Leerdam et al[63], 2003 | January 2000 - January 2001 | Netherlands (Amsterdam area) | Hospital survey (Two university and ten regional hospitals) | P | AUGIB |

| Targownik et al[35], 2006 | 1993 - 2003 | Canada | Administrative database (HPOID) | R | AUGIB |

| Theocharis et al[36], 2008 | January 1995- December 1995 | Greece (Achaia) | Clinical data (Three regional hospitals) | R | AUGIB |

| January - December 2005 | P | ||||

| Kapsoritakis et al[37], 2009 | 1 December 2005 - 30 November 2006 | Greece (Thessaly, Larissa) | Clinical data (University Hospital of Larissa) | P | AUGIB |

| Lanas et al[38], 2009 | 1 January 1996 - 30 December 2005 | Spain | Administrative database (10 hospitals of Spanish NHS) | R | NVUGIB |

| LGIB | |||||

| Loperfido et al[39], 2009 | 1 October 1983 - 31 December 1985 | Italy (Treviso) | Clinical data (Treviso Hospital) | P | AUGIB |

| 1 January 2002 - 31 March 2004 | |||||

| Åhsberg et al[40], 2010 | 1 January - 31 December 1984 | Sweden (Skåne) | Clinical data (Lund University Hospital) | R | NVUGIB |

| LGIB | |||||

| 1 January - 31 December 1994 | NVUGIB | ||||

| LGIB | |||||

| 1 January - 31 December 2004 | NVUGIB | ||||

| LGIB | |||||

| Button et al[41], 2011 | 1 April 1999 - 31 March 2007 | Wales | Linked administrative database (PEDW) | R | UGIB |

| Langner et al[42], 2011 | 2000 – 2005 | Germany | Administrative database (GHS) | R | UGIB |

| Crooks et al[43], 2012 | 1 April 1997 - 30 August 2010 | England | Linked EHR data (GPRD and HES) | R | UGIB |

| Laine et al[44], 2012 | 2001 - 2009 | USA | Administrative claims database (Premier Perspective) | R | UGIB |

| LGIB | |||||

| Miyamoto et al[45], 2012 | 1997 - 2008 | Japan (Aki-Ota, Hiroshima) | Clinical data | R | UGIB |

| Mungan et al[46], 2012 | 6 January - 10 March 2009 | Turkey | Cohort study (ENERGIB survey) | R | NVUGIB |

| Nahon et al[47], 2012 | March 2005 - February 2006 | France | Hospital survey (53 hospitals) | P | UGIB |

| Sangchan et al[48], 2012 | 1 October 2009 - 30 September 2010 | Thailand | Claims and clinical data | R | UGIB |

| Del Piano et al[49], 2013 | June 2006 - June 2007 and December 2008 - December 2009 | Italy | Clinical data (13 hospitals) | P | ANVUGIB |

| Hreinsson et al[50], 2013a | 1 January 2010 - 31 December 2010 | Iceland (Reykjavik) | Clinical data (National University Hospital of Iceland) | P | ALGIB |

| Hreinsson et al[51], 2013b | 1 January 2009 - 31 December 2010 | Iceland (Reykjavik) | Clinical data (National University Hospital of Iceland) | P | AUGIB |

| Cavallaro et al[45], 2014 | January 2001 - December 2010 | Italy (Veneto) | Administrative database (HDRs) | R | UGIB |

| LGIB | |||||

| Marmo et al[53], 2014 | March 2003 - March 2004 and April 2007 - May 2008 | Italy | Administrative database (PNED1 and PNED2) | P | NVUGIB |

| O'Byrne et al[54], 2014 | 1 January 2008 - 31 December 2009 | Canada (Saskat-chewan) | Clinical data (SHR and RQHR) | R | NVUGIB |

| Abougergi et al[64], 2015 | 1989 - 2009 | USA | Administrative database (NIS) | R | UGIB |

| Niikura et al[55], 2015 | 1 July 2010 - 31 March 2012 | Japan | Administrative claims database (DPC) | R | LGIB |

| Taha et al[56], 2015 | 2007 - 2012 | Scotland (Ayrshire) | Clinical data (University Hospital Crosshouse) | R | UGIB |

| Lu et al[57], 2018 | 1 January 2008 - 31 December 2012 | China | Hospital survey (Eight hospitals) | R | NVUGIB |

| Park et al[58], 2018 | February 2011 - December 2013 | South Korea (Daegu, Gyeong-sang) | Clinical data (Eight hospitals) | P | UGIB |

| Wuerth et al[59], 2018 | 2002 - 2012 | USA | Administrative database (NIS) | R | UGIB |

| Ref. | Diagnostic criteria | Total patients, (male) | Age1, (mean) | Population at risk | Re-bleeding | Diagnostic endoscopy2 | In-hospital bleeds3 |

| Schlup et al[24], 1984 | Hematemesis and/or melena | 112 (58.0) | ≥ 15 (61.5) | 120000 - 150000 | 18 (16.1) | Yes | Unclear |

| Katschinski et al[25], 1989 | Hematemesis and/or melena | 1017 (N/A) | All (N/A6) | 789000 | N/A | Yes | Unclear |

| Longstreth[26], 1995 | ICD-9-CM | 258 (63.6) | ≥ 20 (60.6) | 270699 | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| Bramley et al[27], 1996 | Suspected UGIB or LGIB | 252 (46.8) | All (N/A6) | 467760 | 34 (13.5) | Some | Yes |

| Masson et al[28], 1996 | Suspected UGIB or LGIB | 1098 (62.2) | All (N/A6) | 468000 | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| Blatchford et al[60], 1997 | Hematemesis and/or melena; using standard definitions | 1882 (64.2) | ≥ 15 (N/A6) | 2184285 | N/A | Some | Yes |

| El Bagir et al[29], 1997 | Hematemesis and/or melena | 240 (62.5) | ≥ 20 (44.3) | 450000 | N/A | Yes | Unclear |

| Longstreth[30], 1997 | ICD-9-CM | 219 (55.7) | ≥ 20 (67.2) | N/A | 14 (6.7) | Yes | Yes |

| Soplepmann et al[61], 1997 | Hematemesis and/or melena | 270 (66.7) | ≥ 15 (64.2) | 257000 | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| 243 (60.0) | ≥ 15 (58.8) | 159000 | N/A | ||||

| Vreeburg et al[31], 1997 | Hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, or blood admixture upon nasogastric aspiration | 951 (60.0) | All (Mdn: 71) | 1610900 | 156 (16.4) | Yes | Yes |

| Czernichow et al[32], 2000 | Hematemesis and/or melena | 2133 (63) | ≥ 18 (Mdn: 68) | 2926241 | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| Paspatis et al[33], 2000 | Hematemesis, melena or other clinical or laboratory evidence of blood loss from the upper GI tract | 353 (63.5) | ≥ 16 (66.2) | 220000 | 41 (12) | Yes | Yes |

| Tenias Burillo et al[34], 2001 | All admitted patients with UGIB | 779 (62.1) | Adults (63.4) | 180996 | N/A | Yes | Unclear |

| Lewis et al[62], 2002 | ICD-9-CM | N/A | All (N/A) | N/A | N/A | Unclear | Yes |

| van Leerdam et al[63], 2003 | Hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, or blood admixture upon nasogastric aspiration | 769 (56.0) | All (N/A6) | 1612439 | 119 (16.0) | Yes | Yes |

| Targownik et al[35], 2006 | ICD-9 and ICD-10-CA | 1423634 (N/A) | ≥18 (62.0-66.0) | 21944828-24324251 | N/A | Unclear | No |

| Theocharis et al[36], 2008 | Hematemesis, bloody nasogastric aspiration, or melena and clinical/laboratory evidence of acute blood loss from the upper GI tract | 489 (74.4) | > 16 (59.4) | 300078 | 48 (9.9) | Yes | Yes |

| 353 (72.5) | > 16 (66.1) | 326794 | 26 (7.3) | ||||

| Kapsoritakis et al[37], 2009 | All patients hospitalized for acute UGIB | 264 (75.4) | ≥ 16 (65.5) | 228428 | 21 (7.9) | Yes | Yes |

| Lanas et al[38], 2009 | ICD-9-CM | 176634 (N/A) | All (N/A6) | 3281973 - 3681822 | N/A | Unclear | No |

| 57694 (N/A) | |||||||

| Loperfido et al[39], 2009 | ICD-9 | 532 (72.3) | > 15 (61.0) | 231914 | 191 (32.5) | Yes | Yes |

| 513 (64.3) | > 15 (68.7) | 266791 | 40 (7.4) | ||||

| Åhsberg et al[40], 2010 | ICD-8 | 138 (75.0) | Adults (Mdn: 69) | 151711 | N/A | Yes | Unclear |

| 69 (46.0) | Adults (Mdn: 69) | ||||||

| ICD-9 | 123 (60.0) | Adults (Mdn: 73) | 170727 | ||||

| 95 (45.0) | Adults (Mdn: 76) | ||||||

| ICD-10 | 181 (59.0) | Adults (Mdn: 77) | 289560 | ||||

| 125 (54.0) | Adults (Mdn: 75) | ||||||

| Button et al[41], 2011 | ICD-10 | 222995 (54.4) | ≥ 18 (64.1) | N/A | N/A | Some | Yes |

| Langner et al[42], 2011 | ICD-9-GM | 942325 (51.4) | All (N/A6) | N/A | N/A | Unclear | No |

| Crooks et al[43], 2012 | ICD-10 (HES) and Read code system (GPRD) | 347085 | ≥ 18 (N/A6) | N/A | N/A | Unclear | Unclear |

| Laine et al[44], 2012 | ICD-9 | N/A | All (N/A) | N/A | N/A | Unclear | No |

| Miyamoto et al[45], 2012 | Hematemesis and/or melena | 2367 (53.7) | All (67.9) | Approximately 16065 | N/A | Yes | Unclear |

| Mungan et al[46], 2012 | ICD-9/ICD-10 | 423 (67.4) | Adults (57.8) | N/A | 28 (6.6) | Yes | Yes |

| Nahon et al[47], 2012 | Hematemesis and/or melena and/or acute anemia with blood in the stomach | 3203 (66.5) | ≥ 18 (Mdn: 64.1) | N/A | 317 (9.9) | Yes | No |

| Sangchan et al[48], 2012 | ICD-10 | 771115 (69.2) | Adults (58.5) | N/A | N/A | Some | No |

| Del Piano et al[49], 2013 | Presenting to the emergency room for NVUGIB | 1413 (66.0) | All (53.2) | N/A | 77 (5.4) | Yes | No |

| Hreinsson et al[50], 2013a | (1) Passage of bright red blood per rectum or maroon colored without hematemesis and (2) Melena with no bleeding in upper GI endoscopy | 131 (49.7) | ≥ 18 (Mdn: 68) | 151008 | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| Hreinsson et al[51], 2013b | (1) Hematemesis or coffee ground vomit; (2) Melena; and (3) Rectal bleeding with confirmed bleeding on upper gastroendoscopy and negative colonoscopy | 132 (58.0) | 18-105 (Mdn: 71) | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| Cavallaro et al[45], 2014 | ICD-9-CM | 23450 (59.5) | All (64.2) | 4912438 | N/A | Unclear | No |

| 13800 (47.8) | |||||||

| Marmo et al[53], 2014 | Hematemesis, melena or dark, tarry materials on rectal examination | 2317 (65.9) | ≥ 18 (67.9) | N/A | 86 (3.7) | Yes | Yes |

| O'Byrne et al[54], 2014 | ICD-10 | 360 (61.7) | 17-100 (66.5) | 1200000 | 73 (20.3) | Yes | Yes |

| Abougergi et al[64], 2015 | ICD-9-CM | 12664264 (54.5) | All (Mdn: 67.0-70.0) | N/A | N/A | Yes | No |

| Niikura et al[55], 2015 | ICD-10 | 30846 (52.0) | ≥ 20 (Mdn: 74) | N/A | N/A | Unclear | No |

| Taha et al[56], 2015 | ICD-10 | 8694 (62.5) | All (Mdn: 63) | 258370 -260280 | N/A | Unclear | Unclear |

| Lu et al[57], 2018 | (1) Hematemesis and/or melena; (2) Drainage of coffee grounds or fresh blood in the gastric tube; (3) Positive FOBT; and (4) Varices, but endoscopy confirmed that bleeding was unrelated | 2977 (76.5) | ≥ 18 (54.7) | N/A | 87 (2.9) | Yes | Yes |

| Park et al[58], 2018 | Hematemesis, melena, and hematochezia or a suspicious clinical presentation of UGIB such as syncope, epigastric pain, dyspnea, dizziness, altered mental status, or anemia | 1424 (74.1) | ≥ 16 (62.7) | N/A | 110 (7.7) | Yes | No |

| Wuerth et al[59], 2018 | ICD-9-CM | 2432088 (55.0) | ≥ 18 (N/A6) | N/A | N/A | Some | No |

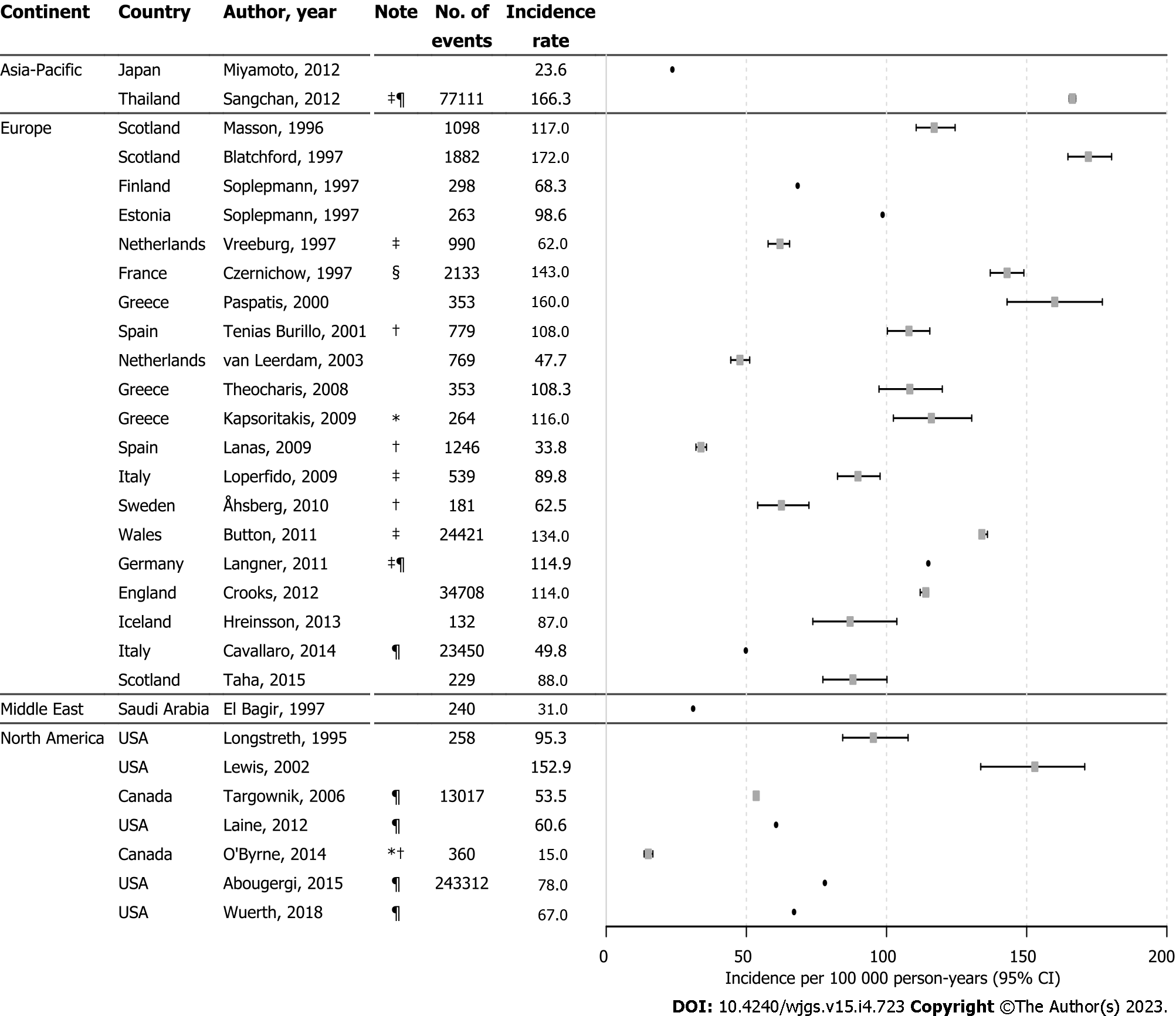

Twenty-nine studies reported incidence rates for UGIB which ranged from 15.0 per 100000 person-years to 172.0 per 100000 person-years over 1980 to 2012 (Figure 1), with high heterogeneity across and within countries. Approximately two-thirds of incidence rates (65.5%) were within the range of 50 to 120 per 100000 person-years. Four studies reported estimates for NVUGIB incidence ranging from 15.0 per 100000 person-years to 108.0 per 100000 person-years, also with high heterogeneity between studies[34,38,40,54]. Incidence rates among studies that included GIB only as primary diagnosis were lower than studies that did not restrict inclusion to primary diagnosis only[35,44,52,59,64], except for when the numerator was the number of hospitalizations[42,48]. A hospital-based survey from France that included out-patient diagnosed GIB reported the highest incidence estimate of 143 per 100000 person-years for the year 1996[32].

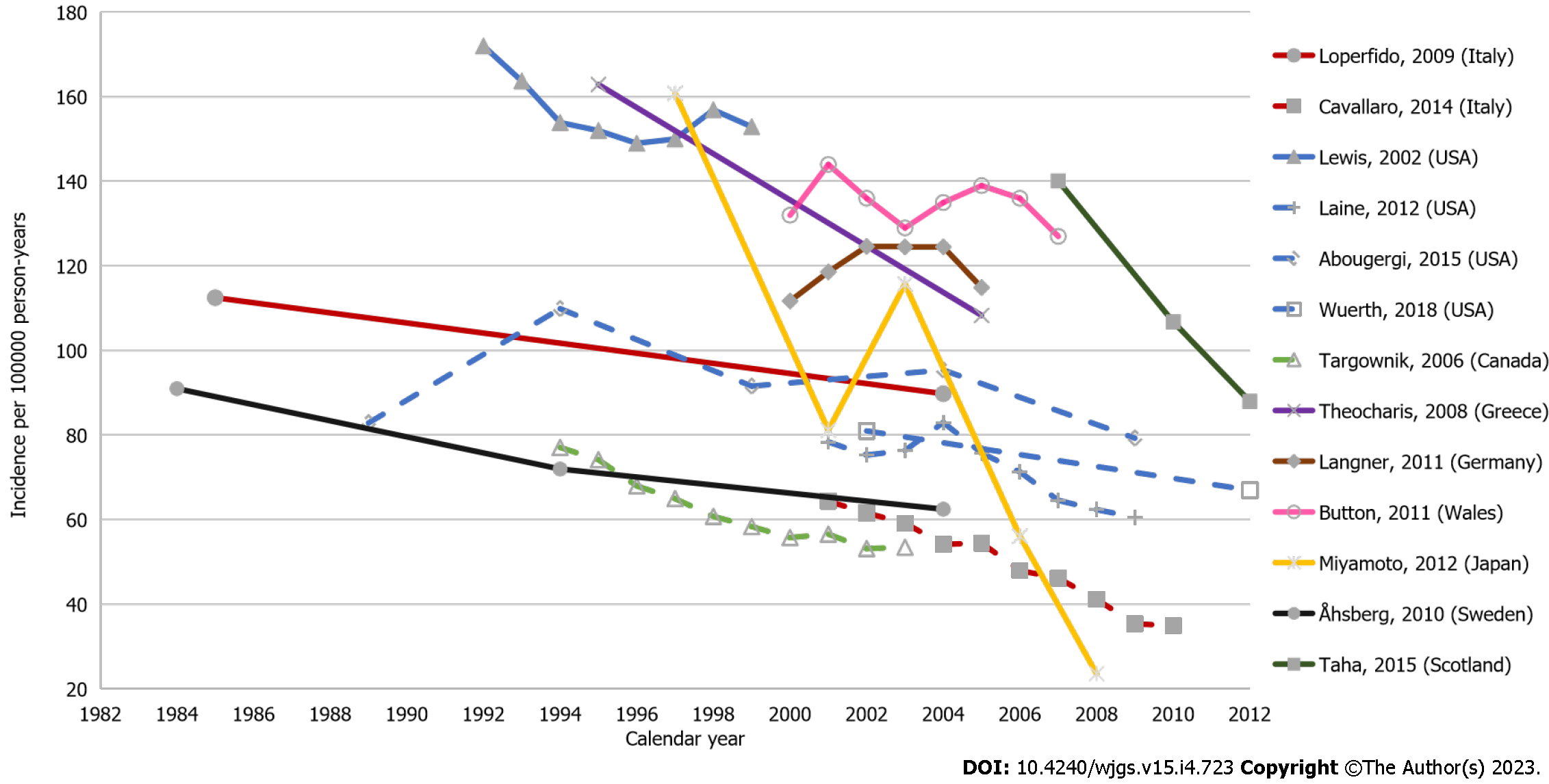

There were thirteen studies that described temporal trends of UGIB incidence within the defined study years. Among these, overall declines in UGIB incidence were seen over time (Figure 2), most notably in Japan, which saw a particularly rapid decline, albeit with a spike in 2003[45]. Other studies described a slight increase in UGIB incidence between 2003–2005 followed by a decline[41,42,44,52,64]. Differences between studies that reported rates from the same country were likely due to different inclusion criteria and GIB definition. Among two studies from Italy in 2004, one reported a rate of 84.8 per 100000 person-years for UGIB incidence with the inclusion of hospital bleeds based on clinical data[39], while the other reported a rate of 52.4 per 100000 person-years for emergency GIB-related admissions from administrative data with a larger sample size[52]. In the US, estimates for UGIB incidence from three administrative database studies, which identified GIB using primary diagnosis codes, ranged from 60 to 110 per 100000 person-years across several timeframes between 1989 and 2012[44,59,64]. Also from the US, a hospital-based study reported higher UGIB incidence at 152.9 per 100000 person-years over their 1992–1999 study period, where GIB cases were not limited to primary diagnosis only[62].

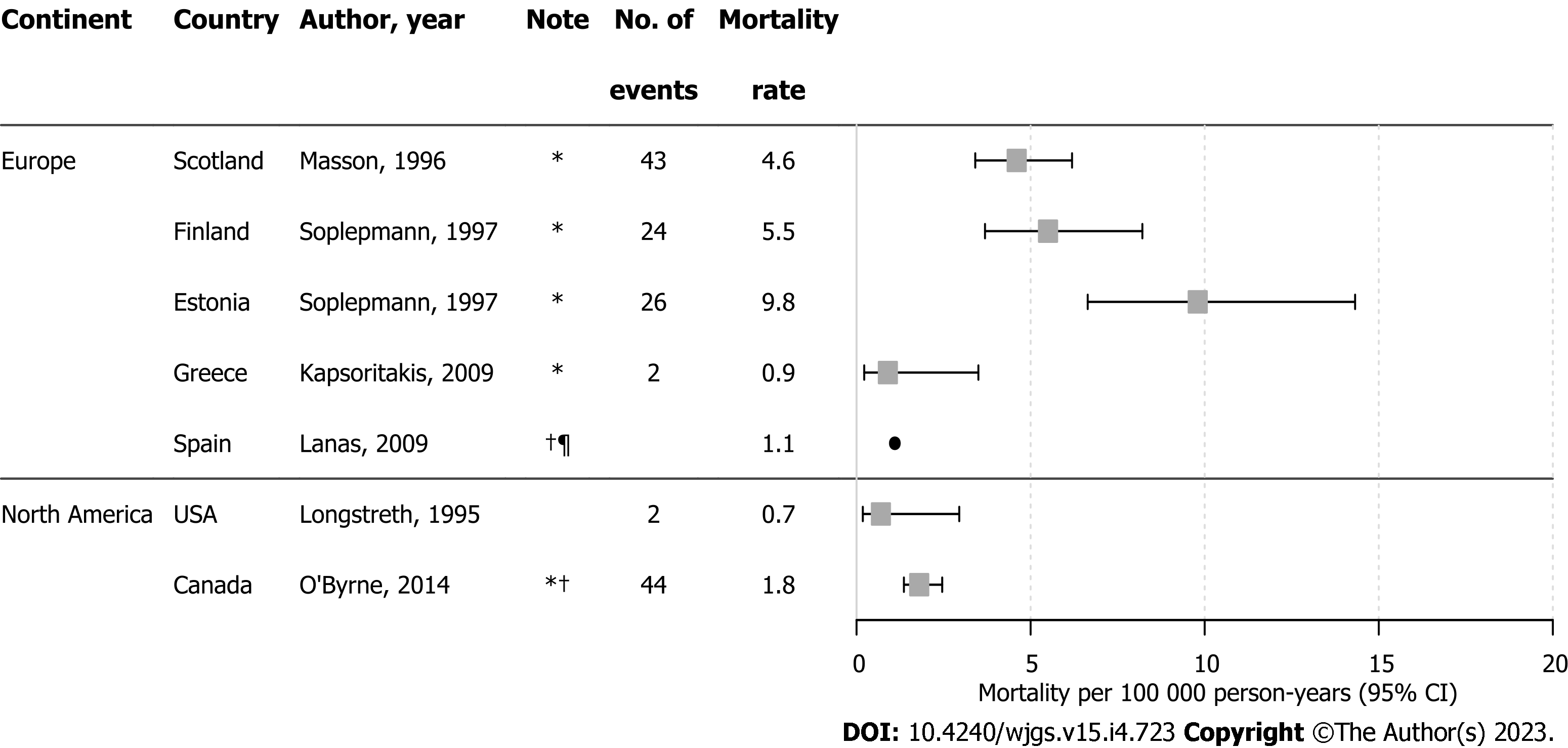

Mortality was reported in six studies; UGIB-related mortality was not reported directly in four and so estimates were calculated from available data[28,37,54,61]. Estimates ranged from 0.88 to 9.75 per 100000 person-years (Figure 3). Two studies with large sample sizes reported mortality rates for NVUGIB as 1.1 per 100000 person-years using clinical data from Spain[38] and 1.83 per 100000 person-years in Canada based on administrative claims[54]; these were lower than most mortality estimates of overall UGIB.

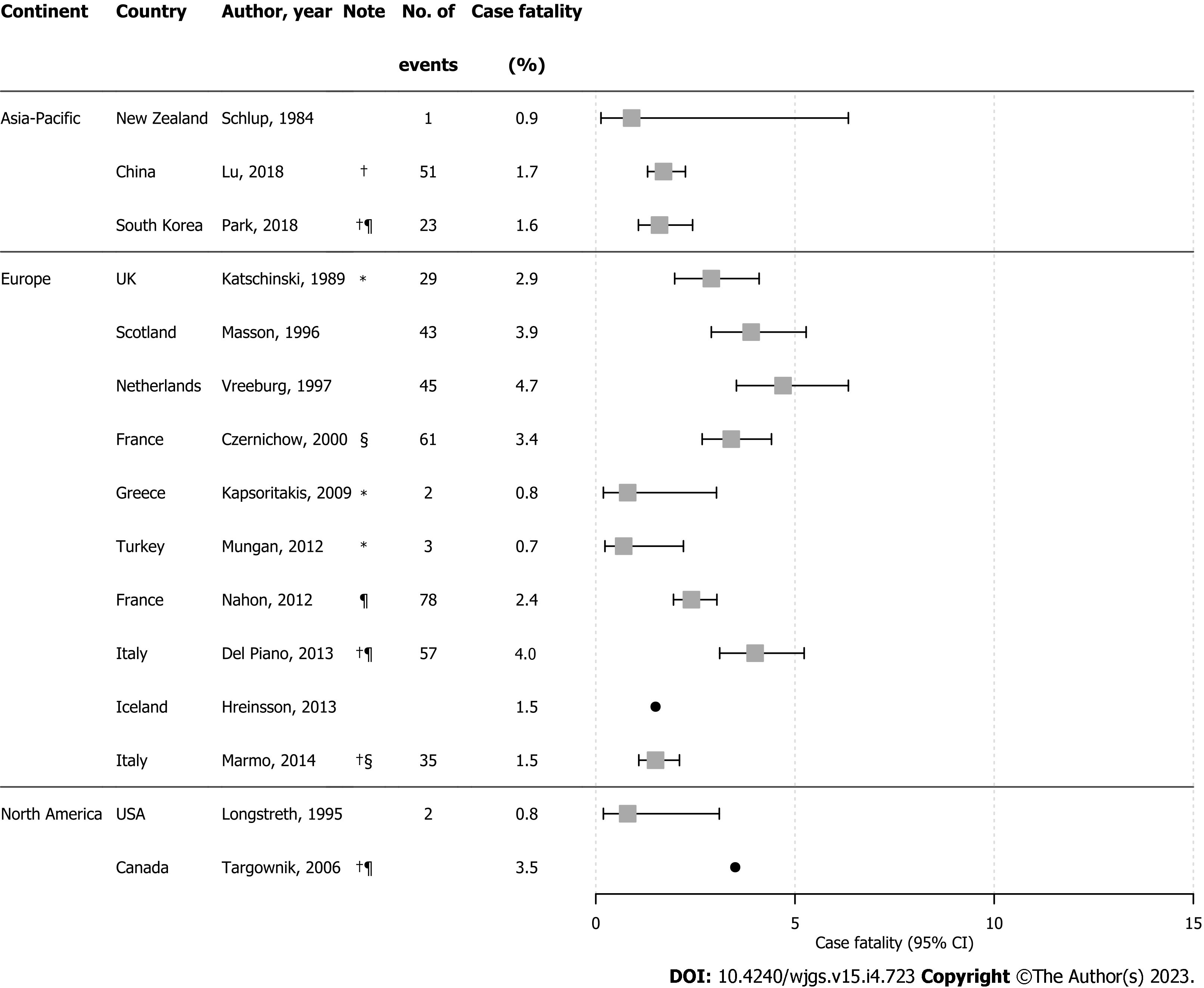

Case-fatality rates for UGIB were reported in 15 studies with estimates ranging from 0.7% to 4.7% (Figure 4). Case-fatality for NVUGIB ranged between 1.6% and 4.0%, with higher rates from studies that restricted to UGIB as the primary diagnosis[25,35,49]. In four studies, the number of UGIB-related deaths was very low, leading to imprecise estimates[24,26,37,46]. UGIB case-fatality rates varied across regions during 1980–2013, although higher rates were reported in earlier years, particularly in Europe.

Six studies reported incidence rates for LGIB; estimates ranged between 20.5 and 87.0 per 100000 person-years[27,30,40,44,50,52], with the lowest estimate from a US claims database in study years from 1990-1993[30] and the highest from a single hospital-based study from Iceland in 2010[50]. In Scotland, the incidence of LGIB was found to be 27 per 100000 person-years based on a study using hospital records for the period 1990–1993[27], while for the same period, a claims-based study from the US reported a rate of 20.5 per 100000 person-years[30]. Another US claims database study reported a LGIB incidence rate of 41.8 per 100000 person-years for the year 2001[44]. Analysis of administrative data from the Veneto region in Italy (with a population around 5 million), reported an incidence of LGIB in 2001 of 27.3 per 100000 person-years[52]. Studies reporting time trends in LGIB incidence found that rates fluctuated across time, with higher rates observed during 2001–2005[44,52]. In a hospital study from Sweden, rates decreased from 55.6 to 43.2 per 100000 person-years over a 10-year period starting from 1994[40].

Three studies reported estimates for LGIB-related mortality[27,38,40]. Using data from 10 hospitals within the Spanish National Health System and covering a population of around 4 million, Lanas et al[38] demonstrated that LGIB-related mortality increased from 0.2 to 1.0 per 100000 person-years between 1996 and 2005. A single-center hospital based study from Grampian and the Northern Isles in Scotland found LGIB-related mortality to be 1.4 per 100000 person-years over a 10-year study period (1994–2004)[27], while over the same time period, an increase in LGIB-related mortality was observed in Sweden from 0.59 to 3.45 per 100000 person-years[40].

Six studies reported LGIB case-fatality rates with estimates ranging from 0.5% to 8.0%[27,30,38,40,50,55]. LGIB case-fatality among patients in Spain fluctuated over 1996–2005, increasing from 2.9% in 1996, peaking at 5.0% in 1999, and declining to 2.6% in 2005[38]. Based on 170727 hospital records in Sweden between January-December 1994, LGIB case-fatality increased from 1.0% to 8.0% over a 10-year study period (1994–2004) albeit based on only 69 LGIB cases[40]. Other reported LGIB case-fatality rates range from 0.5% in a US claims database study on 219 cases between 1990 and 1993[30] to 5.1% from a hospital-based study in Scotland with 252 cases over an overlapping period (1991–1993)[27]. More contemporary LGIB case-fatality rates from Japan and Iceland were reported as 2.5%[55] and 1.2%[50], respectively.

Seven studies reported UGIB rebleeding rates. These ranged from 7.3% to 32.5% with rebleeding rates being generally lower in the more contemporary studies. Five studies reported NVUGIB rebleeding rates ranging from 2.9% to 20.3%. Rebleeding rates for LGIB were reported in two studies covering the 1990s; the rates were 13.5%[27] and 6.7%[30].

Two main potential areas of bias were identified: UGIB/LGIB definition and inadequate information on how missing data were handled (Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 5). Based on the assessment of individual studies, 2 out of 19 studies that used standardized classification methods failed to provide UGIB/LGIB codes, despite adopting ICD criteria for classification[55,56]. Only 12 out of 41 studies described how they handled missing data – by excluding individuals with missing data in their records. The low risk of bias domains were the identification of target population and the appropriate sampling of patients. Thirty-nine percent of studies reported adequate information on the inclusion of patients in the study, and 42% presented thorough descriptive data on patient characteristics (Supplementary Table 6). Only 29% of studies described the generalizability of their results.

Gastrointestinal bleeding is an important clinical event associated with high patient burden and major resource implications for healthcare systems. Our review provides broad insights into the long-term worldwide epidemiology of GIB in the general adult population. Incidence, mortality, and case-fatality rates for GIB were found to vary substantially across and within countries. For UGIB, estimates ranged from 15.0 per 100000 to 172.0 per 100000 person-years for incidence (with a decline seen over time), 0.9 per 100000 to 9.8 per 100000 person-years for UGIB-related mortality, 0.7% to 4.8% for case-fatality, and 7.3%–32.5% for rebleeding. For LGIB, estimates ranged from 20.5 per 100000 person-years to 87.0 per 100000 person-years for incidence, 0.2 per 100000 person-years to 1.0 per 100000 person-years for LGIB-related mortality, 0.5% to 8.0% for case-fatality, and 6.7%–13.5% for rebleeding.

Our results are in line with findings from earlier reports of a decreasing trend of UGIB incidence[15], albeit the data were heterogeneous likely due to methodological differences such as inclusion criteria and the operational definition of GIB. These differences resulted mainly from either restriction to hospital cases or the inclusion of patients where GIB was the sole primary diagnosis. For example, a high UGIB incidence of 143 per 100000 person-years was observed in France, where 16% of the 2133 included UGIB cases were managed out of the hospital setting[32], compared with a much lower rate of 49.0 per 100000 person-years reported in Italy where patients with GIB as the sole primary diagnosis were included[63]. Incidence rates from studies that restricted UGIB cases to those resulting in a hospital admission may have been underestimated. This is noteworthy because over time, UGIB cases deemed at low risk have tended to be treated on an outpatient basis[35]. Similarly, in terms of deaths, exclusion of deaths before hospital arrival would likely result in mortality underestimation, although the assumption that severe GIB cases would be admitted to inpatient settings could lead to overestimations of case-fatality. The clinical definition of GIB differed across studies, and those that used clinical markers for UGIB (such as anemia) reported higher incidence rates[32,58]. In other studies where cases with another primary diagnosis were excluded, incidence rates were generally lower, and possibly underestimated. In addition, among administrative database studies, differences in inclusion criteria were observed in the standardized codes (e.g., ICD-10) used to ascertain GIB. Diagnostic differences in GIB have been reported by others[3], and in our risk of bias assessment, a high proportion of studies demonstrated a high risk of classification bias for GIB cases. Aside from differences in methodologies, heterogeneity in GIB epidemiology over our decades long inclusion period could be attributed to changes in both the prevalence of risk factors and clinical practice over time. Changes in social deprivation[27,30,60,65], administration of acid suppressive therapy with proton-pump inhibitors[31,49,63,65], as well as risk inducing medication use such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have all been associated with GIB prevalence in the literature[11,39,40,66,67]; a detailed review of these was beyond the scope of this review. Incomplete information on patient characteristics was a domain of high risk, which makes it difficult to assess differences in clinical markers across studies.

The limited data on LGIB were unsurprising because, relative to UGIB, it is less commonly encountered in clinical practice, and research would understandably be more focused on the latter. Diagnosis is also more challenging for LGIB as illustrated in one study where 25% of undefined cases of hematochezia, originally suspected to be sourced from the lower GI tract, were later confirmed as UGIB[40]. Additionally, most therapeutic advancements did not benefit bleeding sites beyond the duodenum[68,69] and surgical interventions were less effective for LGIB compared to UGIB due to difficulties in bleeding localization[52]. This could limit the exploration on the epidemiology LGIB, as less impact would be expected on the management of the event upon lacking advancements and studies presenting data on LGIB would remain limited. Our review also revealed limited published data on UGIB-related mortality and case-fatality. Where reported, UGIB-related mortality was low, possibly indicative that of UGIB death is more commonly a result of advanced comorbidities rather than an excessive bleed per se. Previous studies have shown that while peptic ulcer is the most frequent cause of UGIB in hospital settings, death in UGIB cases more commonly occur due to gastric cancer or esophageal varices[25,26,31,61]. With further research on UGIB-related death, clinical management strategies could be devised more effectively to target the predictors of UGIB incidence, independently from those for mortality.

This review has several strengths. We systematically reviewed the literature on the long-term worldwide epidemiology of GIB across geographies, and we are unaware of any previous study to have done this. Systematic reporting of disease epidemiology across geographical regions – where patients may differ in their characteristics and where differences in clinical management through diagnosis and treatment may occur – is important for identifying factors that could influence estimates of occurrence. We identified areas of differences in study methodology and reporting, applying risk of bias assessment, to explicate variability across studies. In terms of limitations, we only included studies written in English, although this has not been associated with systematic bias in other reviews[70,71]. Some articles published before 1991 may not have been captured as database indexing was suboptimal at this time with low sensitivity of keyword search[72]; however, bibliography of relevant articles and reviews were scanned to minimize information bias. Additionally, all studies on variceal bleeding identified during the search were either small and not population-based, and/or had no epidemiological variables of interest reported, therefore we were unable to describe the epidemiology of variceal bleeding. Lastly, estimates were not pooled due to the limited number of included studies and their study heterogeneity, which could limit the applicability of findings to inform about the real-world epidemiology of GIB.

Our systematic literature review describes wide ranging estimates of the long-term epidemiology of GIB, which is likely due to high heterogeneity between studies. Overall, the incidence of UGIB showed a decreasing trend over the years. Epidemiological data were more widely available for UGIB than for LGIB.

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) can be a life-threatening medical event; however, reviews on the overall global epidemiology of the condition are lacking. Previous reviews have instead covered risk factors or prediction scores for GIB or have described the epidemiology of GIB arising from specific etiologies.

No overarching review on the broad and long-term worldwide epidemiology of GIB currently exists. A systematic review would be highly informative for future research in the field to provide a robust overview of GIB incidence, mortality and case-fatality.

The objective was to perform a systematic review of the long-term global epidemiology of both upper GIB (UGIB) and lower GIB (LGIB), covering incidence, mortality and case-fatality of the condition. Such population-based estimates would enable trends over time, and by geography, to be observed, which could have been influenced by changing medical practices, and it would also help identify areas where data are plentiful or lacking.

A search strategy using relevant keywords was conducted using EMBASE® and MEDLINE from 1 January 1965 to 17 September 2019. Conference abstracts, editorials, letters, notes, and short surveys were excluded, as well as randomized controlled trials and interventional studies (as these are performed among selected individuals, and do not enable population-based epidemiological estimates to be calculated). Two authors undertook the screening of titles, abstracts and full-texts of papers. Data on the epidemiological variables of interest were extracted.

Thirty-six studies were included. The main findings were that the incidence of UGIB ranged from 15.0 to 172.0/100000 person-years and the incidence of LGIB ranged from 20.5 to 87.0/100000 person-years, although data for LGIB were more limited than for UGIB. Temporal trends were described in 13 studies and showed an overall decline in upper GIB incidence over time. UGIB mortality rates ranged from 0.9 to 9.8/100000 person-years, and from 0.8 to 3.5/100000 person-years for LGIB; case-fatality rate ranged from 0.7 to 4.8% for UGIB and 0.5 to 8.0% for LGIB.

Substantial variation exists in estimates of GIB epidemiology worldwide, likely due to high heterogeneity between studies, highlighting a lack of consistency in GIB definitions. As data on LGIB epidemiology were sparse, this area should be further explored in future research.

The proposed direction of future research would be to obtain contemporary estimates of UGIB and, especially LGIB epidemiology from large, high quality, population-based studies with good case ascertainment and case validation.

We thank Susan Bromley from EpiMed Communications (Abingdon, UK) for English language editing assistance, funded by Bayer AG.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Germany

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Samadder S, India; Shen F, China S-Editor: Liu GL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu GL

| 1. | Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, Jensen ET, Kim HP, Egberg MD, Lund JL, Moon AM, Pate V, Barnes EL, Schlusser CL, Baron TH, Shaheen NJ, Sandler RS. Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2021. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:621-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 158.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Barkun A, Sabbah S, Enns R, Armstrong D, Gregor J, Fedorak RN, Rahme E, Toubouti Y, Martel M, Chiba N, Fallone CA; RUGBE Investigators. The Canadian Registry on Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding and Endoscopy (RUGBE): Endoscopic hemostasis and proton pump inhibition are associated with improved outcomes in a real-life setting. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1238-1246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tielleman T, Bujanda D, Cryer B. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2015;25:415-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Zuccaro G. Epidemiology of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:225-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Dhere T. Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding. In: Srinivasan S, Friedman LS. Sitaraman and Friedman’s Essentials of Gastroenterology. Newark, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2018: 341–357.. |

| 6. | Sostres C, Lanas A. Epidemiology and demographics of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: prevalence, incidence, and mortality. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2011;21:567-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Lowe D, Travis SP, Murphy MF, Palmer KR. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60:1327-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aoki T, Nagata N, Niikura R, Shimbo T, Tanaka S, Sekine K, Kishida Y, Watanabe K, Sakurai T, Yokoi C, Akiyama J, Yanase M, Mizokami M, Uemura N. Recurrence and mortality among patients hospitalized for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:488-494.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hallas J, Dall M, Andries A, Andersen BS, Aalykke C, Hansen JM, Andersen M, Lassen AT. Use of single and combined antithrombotic therapy and risk of serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2006;333:726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pioppo L, Bhurwal A, Reja D, Tawadros A, Mutneja H, Goel A, Patel A. Incidence of Non-variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Worsens Outcomes with Acute Coronary Syndrome: Result of a National Cohort. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:999-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hernández-Díaz S, Rodríguez LA. Incidence of serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding/perforation in the general population: review of epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Skop BP, Brown TM. Potential vascular and bleeding complications of treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Psychosomatics. 1996;37:12-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jiang HY, Chen HZ, Hu XJ, Yu ZH, Yang W, Deng M, Zhang YH, Ruan B. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:42-50.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barkun A, Leontiadis G. Systematic review of the symptom burden, quality of life impairment and costs associated with peptic ulcer disease. Am J Med. 2010;123:358-66.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin KJ, García Rodríguez LA, Hernández-Díaz S. Systematic review of peptic ulcer disease incidence rates: do studies without validation provide reliable estimates? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:718-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Straube S, Tramèr MR, Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Mortality with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation: effects of time and NSAID use. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Weeda ER, Nicoll BS, Coleman CI, Sharovetskaya A, Baker WL. Association between weekend admission and mortality for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: an observational study and meta-analysis. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gupta A, Agarwal R, Ananthakrishnan AN. "Weekend Effect" in Patients With Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:13-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shingina A, Barkun AN, Razzaghi A, Martel M, Bardou M, Gralnek I; RUGBE Investigators. Systematic review: the presenting international normalised ratio (INR) as a predictor of outcome in patients with upper nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1010-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | de Groot NL, Bosman JH, Siersema PD, van Oijen MG. Prediction scores in gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and quantitative appraisal. Endoscopy. 2012;44:731-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ramaekers R, Mukarram M, Smith CA, Thiruganasambandamoorthy V. The Predictive Value of Preendoscopic Risk Scores to Predict Adverse Outcomes in Emergency Department Patients With Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Systematic Review. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23:1218-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:147-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 812] [Cited by in RCA: 1760] [Article Influence: 176.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6805] [Cited by in RCA: 11639] [Article Influence: 646.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schlup M, Barbezat GO, Maclaurin BP. Prospective evaluation of patients with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. N Z Med J. 1984;97:511-515. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Katschinski BD, Logan RF, Davies J, Langman MJ. Audit of mortality in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65:913-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Longstreth GF. Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:206-210. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Bramley PN, Masson JW, McKnight G, Herd K, Fraser A, Park K, Brunt PW, McKinlay A, Sinclair TS, Mowat NA. The role of an open-access bleeding unit in the management of colonic haemorrhage. A 2-year prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:764-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Masson J, Bramley PN, Herd K, McKnight GM, Park K, Brunt PW, McKinlay AW, Sinclair TS, Mowat NA. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in an open-access dedicated unit. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1996;30:436-442. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Ahmed ME, al-Knaway B, al-Wabel AH, Malik GM, Foli AK. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in southern Saudi Arabia. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1997;31:62-64. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Longstreth GF. Epidemiology and outcome of patients hospitalized with acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:419-424. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Vreeburg EM, Snel P, de Bruijne JW, Bartelsman JF, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the Amsterdam area: incidence, diagnosis, and clinical outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:236-243. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Czernichow P, Hochain P, Nousbaum JB, Raymond JM, Rudelli A, Dupas JL, Amouretti M, Gouérou H, Capron MH, Herman H, Colin R. Epidemiology and course of acute upper gastro-intestinal haemorrhage in four French geographical areas. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Paspatis GA, Matrella E, Kapsoritakis A, Leontithis C, Papanikolaou N, Chlouverakis GJ, Kouroumalis E. An epidemiological study of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Crete, Greece. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:1215-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tenías Burillo JM, Llorente Melero MJ, Zaragoza Marcet A. Epidemiologic aspects on nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a mediterranean region: incidence and sociogeographic and temporal fluctuations. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2001;93:96-105. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Targownik LE, Nabalamba A. Trends in management and outcomes of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: 1993-2003. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1459-1466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Theocharis GJ, Thomopoulos KC, Sakellaropoulos G, Katsakoulis E, Nikolopoulou V. Changing trends in the epidemiology and clinical outcome of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a defined geographical area in Greece. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:128-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kapsoritakis AN, Ntounas EA, Makrigiannis EA, Ntouna EA, Lotis VD, Psychos AK, Paroutoglou GA, Kapetanakis AM, Potamianos SP. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in central Greece: the role of clinical and endoscopic variables in bleeding outcome. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:333-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Polo-Tomás M, Ponce M, Alonso-Abreu I, Perez-Aisa MA, Perez-Gisbert J, Bujanda L, Castro M, Muñoz M, Rodrigo L, Calvet X, Del-Pino D, Garcia S. Time trends and impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1633-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Loperfido S, Baldo V, Piovesana E, Bellina L, Rossi K, Groppo M, Caroli A, Dal Bò N, Monica F, Fabris L, Salvat HH, Bassi N, Okolicsanyi L. Changing trends in acute upper-GI bleeding: a population-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:212-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ahsberg K, Höglund P, Kim WH, von Holstein CS. Impact of aspirin, NSAIDs, warfarin, corticosteroids and SSRIs on the site and outcome of non-variceal upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1404-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Button LA, Roberts SE, Evans PA, Goldacre MJ, Akbari A, Dsilva R, Macey S, Williams JG. Hospitalized incidence and case fatality for upper gastrointestinal bleeding from 1999 to 2007: a record linkage study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:64-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Langner I, Mikolajczyk R, Garbe E. Regional and temporal variations in coding of hospital diagnoses referring to upper gastrointestinal and oesophageal bleeding in Germany. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Crooks CJ, Card TR, West J. Defining upper gastrointestinal bleeding from linked primary and secondary care data and the effect on occurrence and 28 day mortality. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Laine L, Yang H, Chang SC, Datto C. Trends for incidence of hospitalization and death due to GI complications in the United States from 2001 to 2009. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1190-5; quiz 1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 45. | Miyamoto M, Haruma K, Okamoto T, Higashi Y, Hidaka T, Manabe N. Continuous proton pump inhibitor treatment decreases upper gastrointestinal bleeding and related death in rural area in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:372-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Mungan Z. An observational European study on clinical outcomes associated with current management strategies for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (ENERGIB-Turkey). Turk J Gastroenterol. 2012;23:463-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Nahon S, Hagège H, Latrive JP, Rosa I, Nalet B, Bour B, Faroux R, Gower P, Arpurt JP, Denis J, Henrion J, Rémy AJ, Pariente A; Groupe des Hémorragies Digestives Hautes de l’ANGH. Epidemiological and prognostic factors involved in upper gastrointestinal bleeding: results of a French prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:998-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Sangchan A, Sawadpanitch K, Mairiang P, Chunlertrith K, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W, Sutra S, Thavornpitak Y. Hospitalized incidence and outcomes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95 Suppl 7:S190-S195. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Del Piano M, Bianco MA, Cipolletta L, Zambelli A, Chilovi F, Di Matteo G, Pagliarulo M, Ballarè M, Rotondano G; Prometeo study group of the Italian Society of Digestive Endoscopy (SIED). The "Prometeo" study: online collection of clinical data and outcome of Italian patients with acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:e33-e37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Hreinsson JP, Gumundsson S, Kalaitzakis E, Björnsson ES. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding: incidence, etiology, and outcomes in a population-based setting. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 51. | Hreinsson JP, Kalaitzakis E, Gudmundsson S, Björnsson ES. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: incidence, etiology and outcomes in a population-based setting. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:439-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Cavallaro LG, Monica F, Germanà B, Marin R, Sturniolo GC, Saia M. Time trends and outcome of gastrointestinal bleeding in the Veneto region: a retrospective population based study from 2001 to 2010. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:313-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Marmo R, Koch M, Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Grossi E, Rotondano G; PNED 1 and PNED 2 Investigators. Predicting mortality in patients with in-hospital nonvariceal upper GI bleeding: a prospective, multicenter database study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:741-749.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | O'Byrne M, Smith-Windsor EL, Kenyon CR, Bhasin S, Jones JL. Regional differences in outcomes of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Saskatchewan. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:135-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 55. | Niikura R, Yasunaga H, Yamaji Y, Horiguchi H, Fushimi K, Yamada A, Hirata Y, Koike K. Factors affecting in-hospital mortality in patients with lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding: a retrospective study using a national database in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:533-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Taha AS, McCloskey C, Craigen T, Simpson A, Angerson WJ. Occult vs. overt upper gastrointestinal bleeding - inverse relationship and the use of mucosal damaging and protective drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:375-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Lu M, Sun G, Zhang XM, Xv YQ, Chen SY, Song Y, Li XL, Lv B, Ren JL, Chen XQ, Zhang H, Mo C, Wang YZ, Yang YS. Peptic Ulcer Is the Most Common Cause of Non-Variceal Upper-Gastrointestinal Bleeding (NVUGIB) in China. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:7119-7129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Park HW, Jeon SW. Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Non-ulcer and Non-variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Prospective Multicenter Study of Risk Prediction Using a Scoring System. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:3253-3261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Wuerth BA, Rockey DC. Changing Epidemiology of Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage in the Last Decade: A Nationwide Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:1286-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Blatchford O, Davidson LA, Murray WR, Blatchford M, Pell J. Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in west of Scotland: case ascertainment study. BMJ. 1997;315:510-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Soplepmann J, Udd M, Peetsalu A, Palmu A. Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in Central Finland Province, Finland, and in Tartu County, Estonia. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1997;86:222-228. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Lewis JD, Bilker WB, Brensinger C, Farrar JT, Strom BL. Hospitalization and mortality rates from peptic ulcer disease and GI bleeding in the 1990s: relationship to sales of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acid suppression medications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2540-2549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, Geraedts AA, Tijssen JG, Reitsma JB, Tytgat GN. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1494-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 64. | Abougergi MS, Travis AC, Saltzman JR. The in-hospital mortality rate for upper GI hemorrhage has decreased over 2 decades in the United States: a nationwide analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:882-8.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Jensen DM, Cheng S, Kovacs TO, Randall G, Jensen ME, Reedy T, Frankl H, Machicado G, Smith J, Silpa M. A controlled study of ranitidine for the prevention of recurrent hemorrhage from duodenal ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:382-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Thomopoulos KC, Vagenas KA, Vagianos CE, Margaritis VG, Blikas AP, Katsakoulis EC, Nikolopoulou VN. Changes in aetiology and clinical outcome of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding during the last 15 years. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Ohmann C, Imhof M, Ruppert C, Janzik U, Vogt C, Frieling T, Becker K, Neumann F, Faust S, Heiler K, Haas K, Jurisch R, Wenzel EG, Normann S, Bachmann O, Delgadillo J, Seidel F, Franke C, Lüthen R, Yang Q, Reinhold C. Time-trends in the epidemiology of peptic ulcer bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:914-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Arroyo MT, Bujanda L, Gomollón F, Forné M, Aleman S, Nicolas D, Feu F, González-Pérez A, Borda A, Castro M, Poveda MJ, Arenas J; Investigators of the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG). Effect of antisecretory drugs and nitrates on the risk of ulcer bleeding associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulants. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:507-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Zlotnick S, Fort JG; Investigators. Video capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, Moulton K, Clark M, Fiander M, Mierzwinski-Urban M, Clifford T, Hutton B, Rabb D. The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28:138-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 907] [Cited by in RCA: 794] [Article Influence: 61.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Hartling L, Featherstone R, Nuspl M, Shave K, Dryden DM, Vandermeer B. Grey literature in systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study of the contribution of non-English reports, unpublished studies and dissertations to the results of meta-analyses in child-relevant reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Dickersin K. Systematic reviews in epidemiology: why are we so far behind? Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:6-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |