Published online Sep 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i9.918

Peer-review started: March 30, 2022

First decision: June 19, 2022

Revised: July 5, 2022

Accepted: August 16, 2022

Article in press: August 16, 2022

Published online: September 27, 2022

Processing time: 176 Days and 0.6 Hours

Endoscopic resection approaches, including endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection (STER) and endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR), have been widely used for the treatment of sub

To investigate the predictors of difficult endoscopic resection for SMTs from the MP layer at the EGJ.

A total of 90 patients with SMTs from the MP layer at the EGJ were included in the present study. The difficulty of endoscopic resection was defined as a long procedure time, failure of en bloc resection and intraoperative bleeding. Clinicopathological, endoscopic and follow-up data were collected and analyzed. Statistical analysis of independent risks for piecemeal resection, long operative time, and intraoperative bleeding were assessed using univariate and multivariate analyses.

According to the location and growth pattern of the tumor, 44 patients underwent STER, 14 patients underwent EFTR, and the remaining 32 patients received a standard ESD procedure. The tumor size was 20.0 mm (range 5.0–100.0 mm). Fourty-seven out of 90 lesions (52.2%) were regularly shaped. The overall en bloc resection rate was 84.4%. The operation time was 43 min (range 16–126 min). The intraoperative bleeding rate was 18.9%. There were no adverse events that required therapeutic intervention during or after the procedures. The surgical approach had no significant correlation with en bloc resection, long operative time or intraoperative bleeding. Large tumor size (≥ 30 mm) and irregular tumor shape were independent predictors for piecemeal resection (OR: 7.346, P = 0.032 and OR: 18.004, P = 0.029, respectively), long operative time (≥ 60 min) (OR: 47.330, P = 0.000 and OR: 6.863, P = 0.034, respectively) and intraoperative bleeding (OR: 20.631, P = 0.002 and OR: 19.020, P = 0.021, respectively).

Endoscopic resection is an effective treatment for SMTs in the MP layer at the EGJ. Tumors with large size and irregular shape were independent predictors for difficult endoscopic resection.

Core Tip: This was the first study to discuss the predictors of difficult endoscopic resection, including various approaches of submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection, endoscopic full-thickness resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection for submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer at the esophagogastric junction. Our data showed that tumors with greater size and irregular shape were independent predictors of difficult endoscopic resection, which is mainly measured by piecemeal resection, long operative time and intraoperative bleeding.

- Citation: Wang YP, Xu H, Shen JX, Liu WM, Chu Y, Duan BS, Lian JJ, Zhang HB, Zhang L, Xu MD, Cao J. Predictors of difficult endoscopic resection of submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer at the esophagogastric junction. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(9): 918-929

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i9/918.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i9.918

Submucosal tumors (SMTs) of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) are defined as tumors located partially or fully within the area 1 cm proximal to and 2 cm distal to the squamocolumnar junction[1]. Previously, a common view was that periodic endoscopic surveillance was recommended for SMTs smaller than 2.0 cm, which were generally considered benign[2,3], while surgical intervention was the preferred treatment for large lesions. However, some gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) have malignant potential[4]. The enlargement of the tumor may deprive patients of the opportunity for minimally invasive surgery and place a great psychological burden on patients. Furthermore, surgical resection of the cardia may lead to lifelong gastroesophageal reflux and severely impair the quality of life of patients.

In recent decades, endoscopic therapeutic technology has developed rapidly. Endoscopic resection approaches, including endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection (STER) and endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR), have been widely used for the treatment of SMTs located in the upper gastrointestinal tract[5-7]. However, compared to SMTs located in the esophagus or stomach, endoscopic resection of SMTs from the EGJ is much more difficult because of the sharp angle and narrow lumen of the EGJ. SMTs originating from the muscularis propria (MP) in the EGJ (especially those that grow extraluminally and adhere closely to the serosa) make endoscopic resection even more difficult, are accompanied by a long operation time, failure of en bloc resection, perforation, and intraoperative and delayed bleeding.

To date, there have been very few reports on the endoscopic excision of SMTs originating from the MP layer at the EGJ by ESD, STER or EFTR[8,9]. Only limited studies have demonstrated the predictors associated with the difficulty of endoscopic resection[10], which is mainly measured by long procedure time, failure of en bloc resection, or intraoperative and postoperative complications, including perforation and bleeding. The aim of the present study was to identify the predictors of technical difficulties during endoscopic resection of SMTs originating from the MP layer at the EGJ.

This was a retrospective study including 90 consecutive patients admitted to Endoscopy Center, Shanghai East Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine between March 2019 and March 2021. Patients who met the following criteria were included: (1) SMTs, which were located at the EGJ, originating from the MP layer as confirmed by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) without restriction of extraluminal growth; (2) Tumor size ≤ 100 mm; (3) Age > 18 years, irrespective of gender; and (4) No evidence of lymph node involvement or distant metastasis. Patients with severe cardiopulmonary diseases, with coagulation disorders or were taking drugs to promote bleeding, such as ticlopidine, aspirin or warfarin were excluded. All patients signed informed consent forms. The study protocol was in accordance with the guidelines for clinical research and was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethical Review Committee of the Hospital.

Tumors with an oval or globular shape were defined as regularly shaped tumors, while horseshoe-shaped, ginger-shaped, lobulated or polygonal tumors were classified as irregularly shaped tumors. Tumors that were partially located above the anatomic EGJ with the distal edge failing to reach the squamocolumnar junction were considered esophagocardia tumors. The tumor of which the center was within the anatomic EGJ and that straddled the squamocolumnar junction was named the cardia tumor. Tumors that were partially located below the anatomic EGJ with the proximal edge failing to reach the squamocolumnar junction were defined as gastrocardia tumors[11].

En bloc resection is defined as a tumor removed in a single piece, with the capsule intact. Complete resection was defined as a tumor removed with no apparent residual tumor at the resection site (assessed macroscopically by the endoscopist) and with negative margins on pathologic examination. A tumor with an oval or globular shape was defined as a tumor with a regular shape[12]. Procedure time was defined as the time from the beginning of the injection to the withdrawal of the endoscope. Intraoperative bleeding was defined as bleeding that could not be controlled by a single session of hemocoagulation and that required multiple hemoclips for hemocoagulation. No visible bleeding or minor bleeding that stops spontaneously or is easily controlled by a single session of hemocoagulation was classified into the no bleeding group[13].

The operation was performed using a single-channel endoscope (GIF-Q260J, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and/or a dual-channel endoscope (GIF-2TQ260 M, Olympus). A carbon dioxide insufflator (UCR, Olympus) was used in all procedures. Other equipment and accessories included a high-frequency generator (VIO 200 D, ERBE, Germany), an argon plasma coagulation (APC 2, ERBE), an endoscopic flushing pump (Olympus Medical Systems), a transparent cap (D-201-11804, Olympus Medical Systems), an injection needle (VIN-23, COOK Medical Europe Ltd.), a hook knife (KD-620LR, Olympus Medical Systems), a dual knife (KD-650 L, Olympus Medical Systems), an insulated-tip knife (KD-611 L, IT2, Olympus Medical Systems), sterile hot snare (MTN-PFS-A-28/23, MTN-PFS-E-36/23, Micro-Tech, Nanjing, China), hemostatic clips (ROCC-D-26-195-C, ROCC-F-26-195-C, Micro-Tech, Nanjing, China), and Coagrasper (HBF-23/2000, Micro-Tech, Nanjing, China). A mixed solution of glycerin fructose containing 10% glycerol, 5% fructose, and indigo carmine was used for submucosal injection.

All patients received general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. The patient was placed in a left lateral decubitus position. For tumors located in the esophagocardia or cardia region, STER was mainly selected. ESD was chosen for gastrocardia SMTs. EFTR was chosen for tumors with a predominant extraluminal growth patterns located in the gastrocardia region.

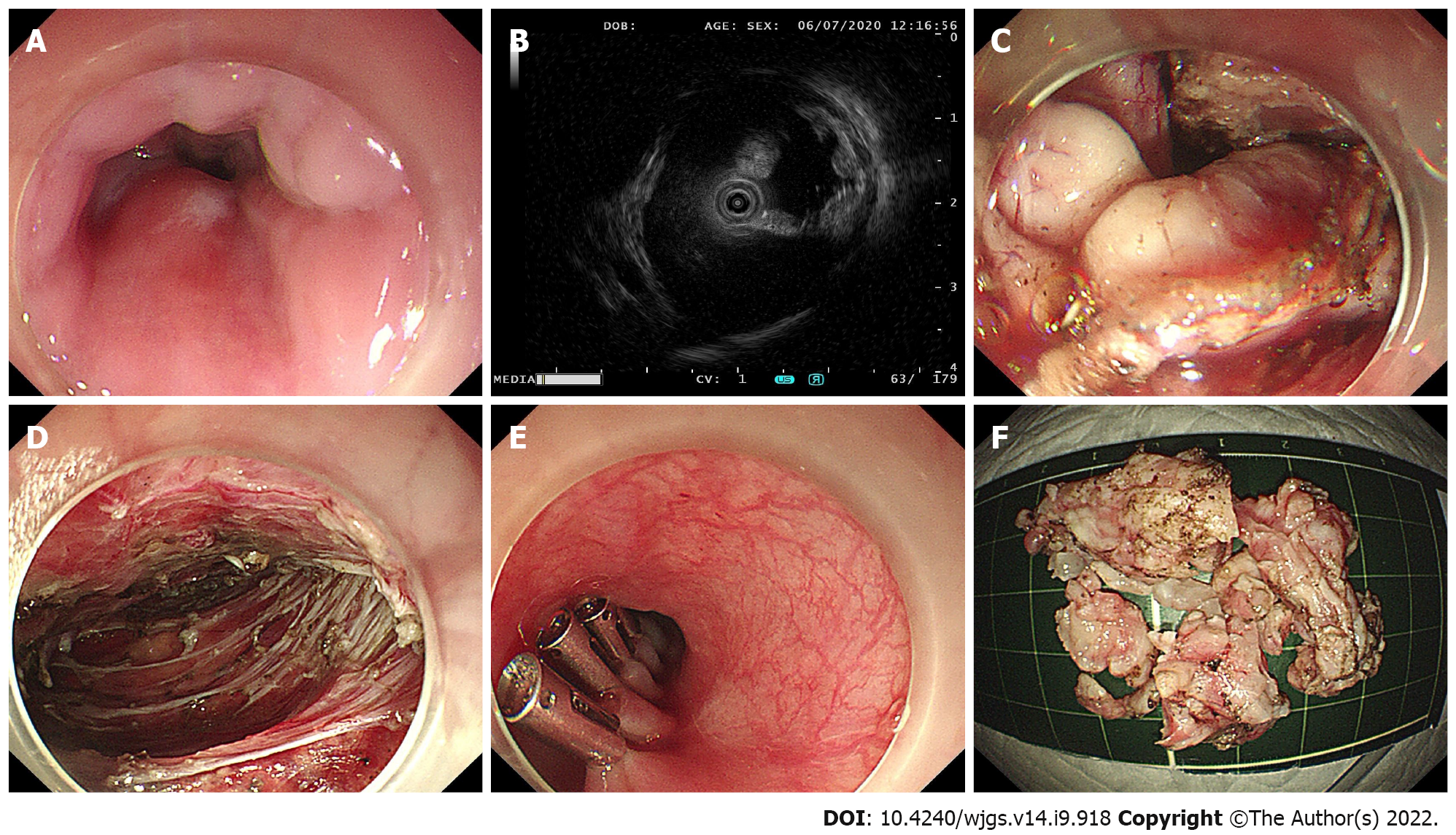

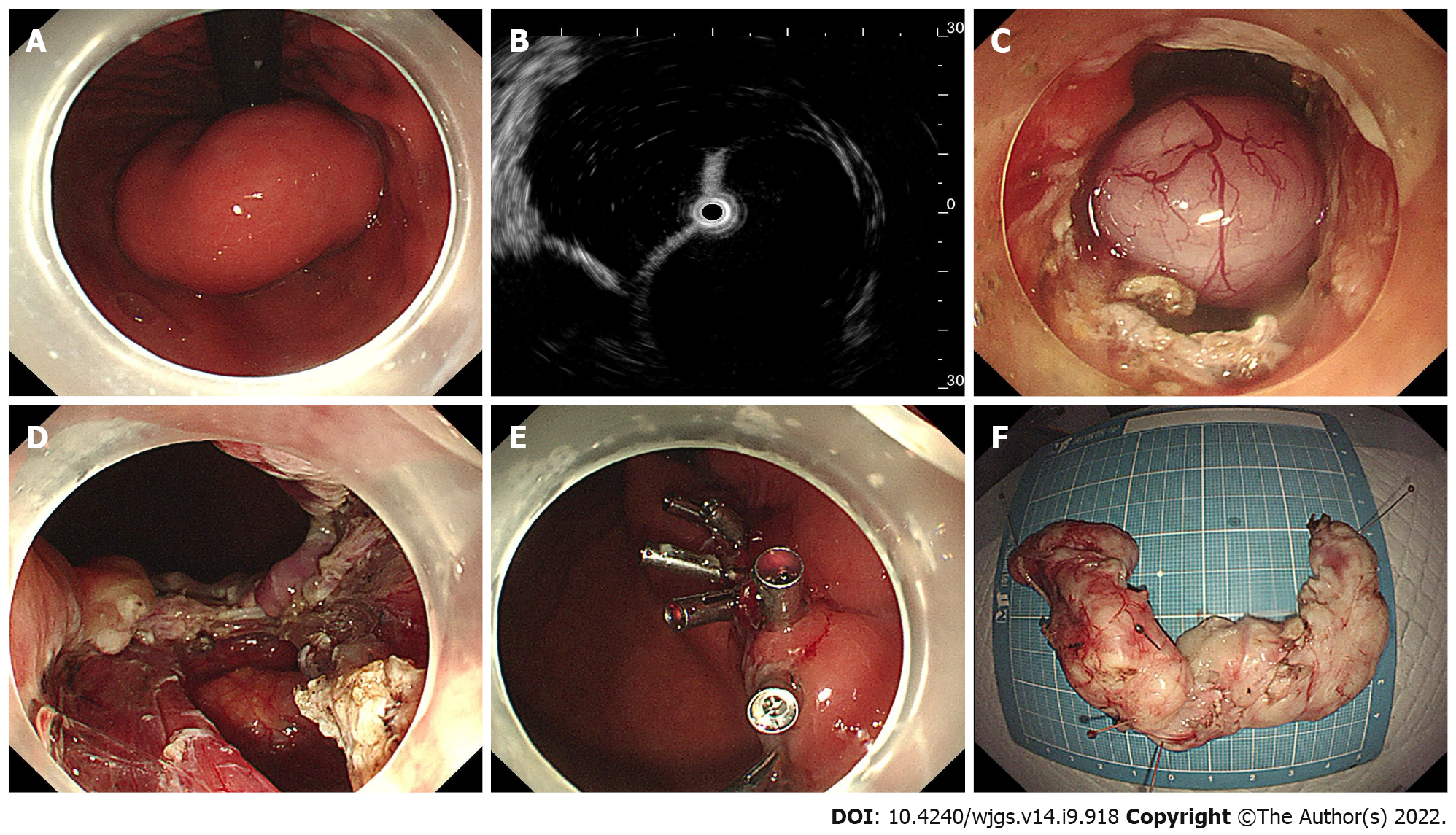

Briefly, ESD was performed in a standardized way starting with injection, mucosal incision, and submucosal dissection at the lesion’s distal margin[4]. Afterward, the tumor was dissected along the capsule. Any macroscopic vessels on the wound surface were electrically coagulated by argon plasma coagulation to prevent delayed bleeding, and metal clips were used to close the deeply dissected areas if needed. When there was a muscularis defect after ESD, purse-string suturing was performed. The STER procedure includes creation of the submucosal tunnel, resection of the SMT, tumor retrieval, hemostasis and closure of the tunnel entry site with 4 to 6 metal clips (Figure 1)[14]. EFTR consists of five steps: Marking of the tumor location, submucosal injection, exposure of the lesion, full-thickness resection and purse-string suture with a Nylon loop and metal clips (Figure 2).

The postoperative observations mainly included complaints of chest or abdominal pain, fever, and gas-related complications such as subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax, pneumoperitoneum, and mediastinal emphysema. All patients fasted for one day and were administered proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics. The patients were started on fluid food first and gradually transitioned to a normal diet when there were no abnormal clinical manifestations.

Resected specimens were fixed in 10% formalin for 48 h. Immunohistochemical staining for CD117, CD34, smooth muscle actin, and S-100 markers was used to identify tumor subtypes. The histological type was determined using the 2010 WHO classification of digestive tumors[15].

All patients were followed up with standard endoscopy at 3, 6, and 12 mo during the first year to observe the healing of the wound and to check for residual tumors or recurrence and thereafter annually. For patients with GISTs, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan/magnetic reso

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 25.0, Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous variables are presented as medians (ranges), and qualitative data are presented as frequencies. Statistical analysis of independent risks for piecemeal resection, long operative time, and intraoperative bleeding were assessed using univariate and multivariate analyses. The relationship between age and tumor size was analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis. P < 0.05 was considered the cutoff value for statistical significance.

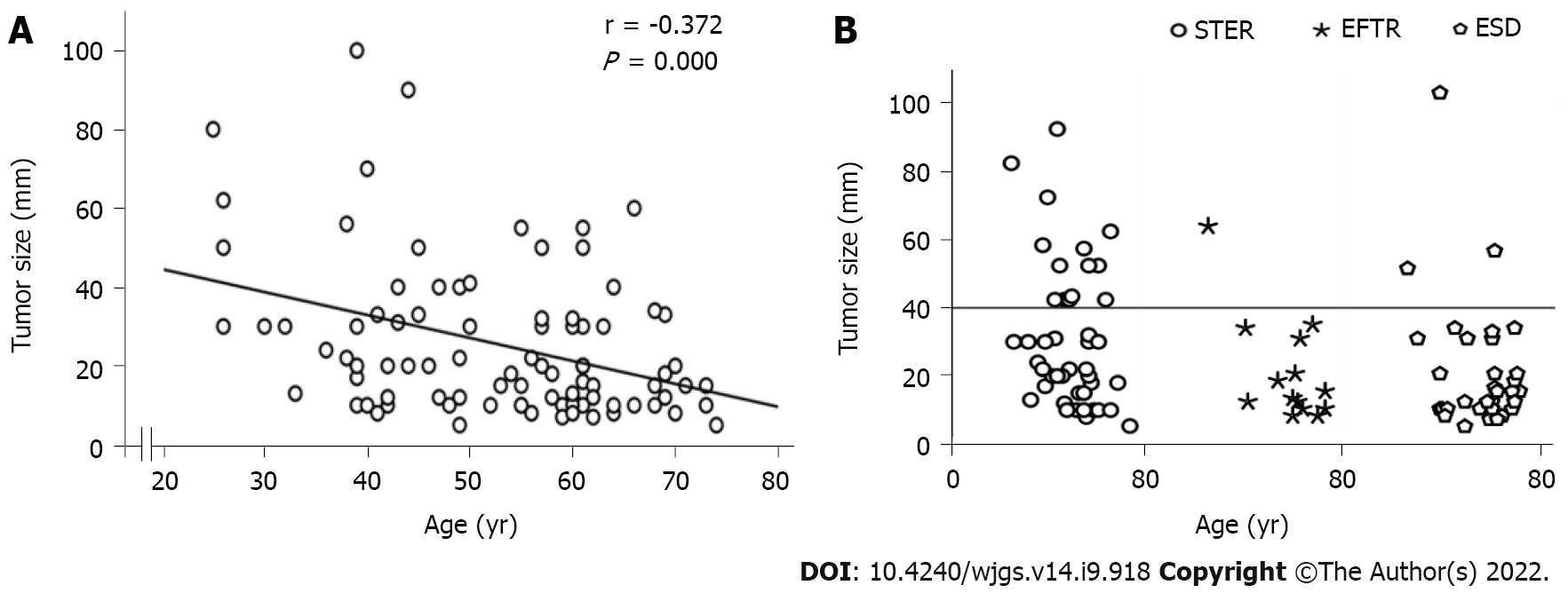

Ninety patients with SMTs originating from the MP layer at the EGJ were included in the present study (Table 1). There were 42 males and 48 females, with a mean age of 55.5 years (range 25.0–74.0 years). The tumor size was 20.0 mm (range 5.0–100.0 mm). The tumor size of GISTs was 18.0 mm (range 8.0–34.0 mm). Fourty-seven out of 90 Lesions (52.2%) were regularly shaped, while the remaining lesions (43/90, 47.8%) were irregularly shaped. Of the 90 SMTs, 25 tumors were located in the esophagocardia region, 26 tumors were located in the cardia region, and 39 were defined as gastrocardia tumors. In terms of the growth pattern, 17 tumors were predominantly extraluminal, and 73 were predominantly intracavitary. There was a significant negative correlation between age and tumor size (Figure 3A).

| Variable | Number |

| Age, median (range), yr | 55.5 (25.0–74.0) |

| Male/Female, n (%) | 42/48 (46.7/53.3) |

| Location, n (%) | |

| Esophagocardia | 25 (27.8) |

| Cardia | 26 (28.9) |

| Gastrocardia | 39 (43.3) |

| Tumor diameter, median (range), mm | 20.0 (5.0–100.0) |

| Shapes of lesion, n (%) | |

| Regular | 47 (52.2) |

| Irregular | 43 (47.8) |

| Growth pattern, n (%) | |

| Predominant extraluminal | 17 (18.9) |

| Predominant intracavitary | 73 (81.1) |

| Surface, n (%) | |

| Smooth | 77 (85.6) |

| Reddish and erosive | 13 (14.4) |

| Surgical approach, n (%) | |

| STER | 44 (48.9) |

| EFTR | 14 (15.6) |

| ESD | 32 (35.5) |

| En bloc resection, n (%) | 76 (84.4) |

| Operation time, median (range), min | 43 (16–126) |

| Intraoperative bleeding, n (%) | |

| Bleeding group | 17 (18.9) |

| No bleeding group | 73 (81.1) |

| Histopathology, n (%) | |

| Leiomyoma | 71 (78.9) |

| GIST | 18 (20.0) |

| Schwannoma | 1 (1.1) |

| Follow-up time, median (range), months | 16.4 (6.0–26.0) |

In the present study, 44 patients underwent STER, 14 patients underwent EFTR, and the remaining 32 patients received a standard ESD procedure. Tumors larger than 4.0 cm accounted for 31.8%, 7.1% and 9.4% of all tumors in the STER group, EFTR group and ESD group, respectively (Figure 3B). All lesions were successfully removed, and the complete resection rate was 100%. The operation time was 50 min (range 18–126 min) in the STER group, 55 min (range 23–108 min) in the EFTR group and 36 min (range 16–116 min) in the ESD group. Seventy-six out of 90 tumors were en bloc resected, whereas 14 Lesions underwent piecemeal resection. The en bloc resection rates were 77.3%, 92.9% and 90.6% in the STER group, EFTR group and ESD group, respectively. Although the en bloc resection rate in the STER group decreased compared to that in the EFTR group and ESD group, the decrease was not statistically significant. The en bloc resection rate of GIST was 100% (18/18).

Intraoperative bleeding requiring multiple hemoclips and hemocoagulation occurred in 8 (8/44, 18.2%), 3 (3/14, 21.4%) and 6 (6/32, 18.8%) patients in the STER group, EFTR group and ESD group, respectively (Table 2). None of the patients had bleeding greater than 150 mL. No adverse events that required therapeutic intervention occurred during or after the procedures. All defects could be closed completely using metal clips or purse-string suture with a Nylon loop and metal clips if needed. A 20-gauge needle was used to relieve the pneumoperitoneum during EFTR. Two patients had low-grade fever, which was relieved quickly without any treatment during the postoperative period. Mild abdominal pain and chest pain, which spontaneously disappeared 2 days after the procedure, were reported in 2 and 2 patients, respectively. None of the patients presented with delayed bleeding, secondary peritoneal or abdominal infections, GI tract leakage, or postoperative stenosis. There were 71 Leiomyomas (78.9%), 1 schwannoma (1.1%), and 18 GISTs (20%, 11 with very low risk, 5 with low risk, 2 with moderate risk) (Table 1).

| Variable | STER | EFTR | ESD |

| Tumor diameter, n (%) | |||

| < 30 mm | 23 (52.3) | 10 (71.4) | 23 (71.9) |

| ≥ 30 mm | 21 (47.7) | 4 (28.6) | 9 (28.1) |

| Location, n (%) | |||

| Esophagocardia | 19 (43.2) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (18.8) |

| Cardia | 18 (40.9) | 2 (14.3) | 6 (18.8) |

| Gastrocardia | 7 (15.9) | 12 (85.7) | 20 (62.4) |

| Shapes of lesion, n (%) | |||

| Regular | 16 (36.4) | 11 (78.6) | 20 (62.5) |

| Irregular | 28 (63.6) | 3 (21.4) | 12 (37.5) |

| Growth pattern, n (%) | |||

| Predominant extraluminal | 6 (13.6) | 11 (78.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Predominant intracavitary | 38 (86.4) | 3 (21.4) | 32 (100.0) |

| Histopathology, n (%) | |||

| Leiomyoma | 42 (95.4) | 4 (28.6) | 25 (78.1) |

| GIST | 1 (2.3) | 10 (71.4) | 7 (21.9) |

| Schwannoma | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.0) |

| Operation time, median (range), min | 50 (18–126) | 55 (23–108) | 36 (16–116) |

| En bloc resection, n (%) | 34 (77.3) | 13 (92.9) | 29 (90.6) |

| Intraoperative bleeding, n (%) | |||

| Bleeding group | 8 (18.2) | 3 (21.4) | 6 (18.8) |

| No bleeding group | 36 (81.8) | 11 (78.6) | 26 (81.3) |

As shown in Table 3, younger age (< 60 years), tumors with larger size and irregular shape were significant risk factors for piecemeal resection. The piecemeal resection rate in tumors with large size and irregular shape was significantly higher than that in tumors with small size and regular shape. The piecemeal resection rate of tumors in younger patients (< 60 years) was higher than that in older patients (> 60 years). Other clinical characteristics, including sex, tumor location, growth pattern, tumor surface, histopathology and surgical approach, had no significant impact on piecemeal resection.

| Variable | En bloc resection and piecemeal resection | Operative times ≥ 60 min and < 60 min | Bleeding and no bleeding during the procedure | |||

| Univariate analysis, OR (95%CI), P value | Multivariate analysis, OR (95%CI), P value | Univariate analysis, OR (95%CI), P value | Multivariate analysis, OR (95%CI), P value | Univariate analysis, OR (95%CI), P value | Multivariate analysis, OR (95%CI), P value | |

| Age, (yr) | ||||||

| < 60 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| ≥ 60 | 0.095 (0.012–0.763), 0.027 | 0.082 (0.007–0.929), 0.043 | 0.648 (0.260–1.614), 0.351 | 0.896 (0.172–4.677), 0.896 | 0.828 (0.276–2.485), 0.736 | 1.226 (0.234–6.419), 0.809 |

| Sex, No. | ||||||

| Female | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Male | 1.171 (0.374–3.665), 0.786 | 1.807 (0.334–9.776), 0.492 | 1.111 (0.465–2.655), 0.813 | 1.089 (0.247–4.799), 0.911 | 0.760 (0.261–2.215), 0.615 | 1.101 (0.225–5.380), 0.906 |

| Shape of lesion, No. | ||||||

| Regular shape | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Irregular shape | 19.933 (2.477–160.405), 0.005 | 18.004 (1.340–241.863), 0.029 | 9.491 (3.324–27.102), 0.000 | 6.863 (1.160–40.602), 0.034 | 12.054 (2.561–56.733), 0.002 | 19.020 (1.570–230.493), 0.021 |

| Tumor diameter | ||||||

| < 30 mm | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| ≥ 30 mm | 14.7270 (3.043–71.279), 0.001 | 7.346 (1.191–45.323), 0.032 | 33.150 (9.855–111.510), 0.000 | 47.330 (8.411–266.322), 0.000 | 21.316 (4.456–101.977), 0.000 | 20.631 (3.066–138.803), 0.002 |

| Surgical approach | ||||||

| STER | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| ESD | 0.352 (0.088–1.401), 0.138 | 0.635 (0.088–4.572), 0.652 | 0.404 (0.144–1.134), 0.085 | 1.554 (0.217–11.120), 0.661 | 1.038 (0.321–3.354), 0.950 | 2.696 (0.372–19.537), 0.326 |

| EFTR | 0.262 (0.030–2.251), 0.222 | 1.596 (0.039–65.206), 0.805 | 1.083 (0.321–3.659), 0.897 | 7.233 (0.335–156.259), 0.207 | 1.227 (0.277–5.439), 0.787 | 37.935 (0.849–1694.936), 0.061 |

| Location | ||||||

| Esophagocardia | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Cardia | 0.576 (0.141–2.349), 0.442 | 0.371 (0.059–2.342), 0.291 | 1.304 (0.422–4.027), 0.645 | 0.824 (0.132–5.134), 0.836 | 0.576 (0.141–2.349), 0.442 | 0.282 (0.045–1.772), 0.177 |

| Gastrocardia | 0.362 (0.091–1.443), 0.150 | 1.407 (0.115–17.261), 0.789 | 0.698 (0.239–2.044), 0.512 | 0.582 (0.051–6.572), 0.661 | 0.693 (0.203–2.368), 0.558 | 0.808 (0.055–11.832), 0.876 |

| Growth pattern | ||||||

| Predominant intracavitary | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Predominant extraluminal | 0.288 (0.035–2.373), 0.248 | 0.272 (0.016–4.484), 0.362 | 1.932 (0.661–5.649), 0.229 | 5.522 (0.480–63.514), 0.170 | 0.516 (0.106–2.505), 0.411 | 0.086 (0.002–3.016), 0.176 |

| Surface | ||||||

| Smooth | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Reddish and erosive | 1.800 (0.427–7.593), 0.424 | 0.707 (0.097–5.141), 0.732 | 1.783 (0.542–5.862), 0.341 | 1.315 (0.203–8.534), 0.774 | 2.188 (0.584–8.192), 0.245 | 2.059 (0.234–18.133), 0.515 |

| Histopathology | ||||||

| Leiomyoma | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| GIST/Schwannoma | 0.248 (0.030–2.027), 0.193 | 1.513 (0.072–31.658), 0.790 | 0.849 (0.288–2.508), 0.767 | 0.632 (0.055–7.297), 0.713 | 0.763 (0.195–2.988), 0.698 | 2.037 (0.122–34.081), 0.621 |

According to univariate and multivariate analyses, risk factors for a long operative time (≥ 60 min) included the shape and size of the tumor. As shown in Table 3, tumor size in the long operative time group (≥ 60 min) was significantly larger than that in the short operative time group (< 60 min). Moreover, the majority of tumors in the group with a long operative time (≥ 60 min) exhibited an irregular shape, while the tumors in the group with a short operative time (< 60 min) were prone to be regularly shaped.

Similarly, large tumor size and irregular shape were independent risk factors for intraoperative bleeding (Table 3). The occurrence of intraoperative bleeding had no significant correlation with age, sex, tumor location, surgical approach, growth pattern, tumor surface or histopathology.

The overall median follow-up period was 16.4 mo (range 6.0-26.0 mo), and all patients were free from stenosis of the EGJ, residual, local recurrence or distant metastasis during the follow-up period. None of the patients died during the follow-up period.

This is the first study discussing the predictors of difficult endoscopic resection, including various approaches of STER, EFTR and ESD, for SMTs originating from the MP layer at the EGJ. Our data showed that tumors with greater size and irregular shape were independent predictors of piecemeal resection, long operative time and intraoperative bleeding.

To date, endoscopic resection has been considered an effective, reliable and safe method to remove SMTs in the deep layer of the EGJ. The difficulty of endoscopic resection is mainly due to the long procedure time, failure of en bloc resection, or intraoperative and postoperative complications. As previously reported, there were no serious complications during the operation, such as major bleeding, perforation or death, indicating that all complications were controllable[9,11,12,16]. In the present study, 90 SMTs that originated from the MP layer at the EGJ were included. The location of SMTs mainly determines which approach of endoscopic resection is chosen to remove the lesion. STER, which was developed by Xu et al[14] for the resection of upper gastrointestinal SMTs originating from the MP layer, is the first choice for tumors located in the esophagocardia or cardia region since it has advantages in maintaining the integrity of gastroesophageal mucosa[14]. ESD is an alternative approach for the resection of gastrocardia SMTs for which the submucosal tunnel between the submucosal and MP layers is not always easy to create. EFTR was mainly selected for tumors with a predominant extraluminal growth pattern located in the gastrocardia region.

No major intraoperative or delayed bleeding or perforation occurred during the procedure. No sign of postoperative stenosis was found during the follow-up period. This may be related to the absence of circumferential lesions. There was a circular lesion in the middle of a patient’s esophagus at our center. No stenosis occurred after STER resection, but muscularis defects were the reason for the diverticular appearance. Stenosis depends on the area of the mucosal defect after ESD and EFTR resection.

Our data revealed that although there was no significant difference, the operation time in the STER group and EFTR group was increased compared to that in the ESD group. This result may be attributed to the time required for creating the submucosal tunnel between the submucosal and MP layers to expose the lesion in the STER group and for occluding the gastric wall defect by the loop-and-clip closure technique. The overall complete resection rate and en bloc resection rate were 100% and 84.4%, respectively. There was no significant difference in the en bloc resection rate or intraoperative bleeding among the three groups.

We evaluated the predictors of en bloc resection, long operative time and intraoperative bleeding. Tumors with greater size and irregular shape and younger age (< 60 years) were significant risk factors for piecemeal resection. Tumors with greater size and irregular shape were the significant contributors to piecemeal resection. Chen et al[12] reported that STER provided a 90.6% en bloc resection rate for upper gastrointestinal SMTs[12]. However, in the present study, the en bloc resection rate in the STER group was only 77.3%, which is lower than that in the ESD group or EFTR group. In Chen’s study, the maximum size of the tumor was 5.0 cm in diameter since they considered that implementation of STER for SMTs with a long diameter ≤ 5.0 cm and a transverse diameter ≤ 3.5 cm could facilitate a high en bloc resection rate[6]. In the present study, the maximum tumor size was 9.0 cm, and tumors larger than 4.0 cm accounted for 31.8% of all tumors in the STER group. Furthermore, the percentage of irregularly shaped tumors in the STER group was 63.6%, which was significantly higher than that in the ESD and EFTR groups. Tumors with large size and irregular shape would be difficult for endoscopists to successfully achieve en bloc resection by STER because of limited space and poor exposure of operative filed in the created submucosal tunnel. In addition, although some large lesions were resected intactly, it was difficult to remove them from the submucosal tunnel due to the high risk of laceration of mucosa at the entrance of the tunnel[14,17]. Importantly, all lesions that received piecemeal resection in the present study were leiomyomas. Similar to previous studies, our data demonstrated that there was no residue or recurrence in lesions that received piecemeal resection during the follow-up period[12,18]. Interestingly, younger age (< 60 years) was one of the independent predictors of piecemeal resection. We considered that the unexpected result was mainly due to the significant negative correlation between tumor size and age.

Similarly, large size and irregular shape were independent predictors for procedures requiring a long operative time (≥ 60 min). A previous study suggested that the maximum size of the lesion removed by STER should be less than 35 mm in diameter, since the large tumor size and narrow lumen in the submucosal tunnel may result in a limited operating field[19]. However, there is a controversial opinion considering that the improvement and maturity of STER technology has made the resection of large tumors feasible. In the present study, the maximum size of the lesion removed successfully by STER was 90 mm, with no recurrence during follow-up. Furthermore, for resection of tumors at the EGJ, it is crucial to inject a small dose of indigo carmine into the submucosa around the tumor location to aid in delineating the submucosal tunnel, and subsequently decreasing the procedure time. The risk of aspiration pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis, and cardiorespiratory distress may increase because of the long procedure time. Thus, it is necessary to fully evaluate the size and shape of the tumor by EUS and radiological examination before the procedure. Tumors with greater size and irregular shape were also independent predictors for intraoperative bleeding. For irregularly shaped large tumors, extra care should be paid to fully expose and pretreat the blood vessels to prevent bleeding.

The current study has several limitations. First, this study is a single-center retrospective study with a relatively small sample size, which may result in the variation between the approach of endoscopic resection and tumor size. Second, the procedures of endoscopic resection were not performed by the same endoscopist. A short follow-up period (range 6–26 mo) is the third limitation. Thus, a prospective, large-scale, randomized controlled study with a long-term follow-up period is necessary in the future to validate the observed results.

Endoscopic resection is effective and safe for SMTs in the MP layer at the EGJ. Tumors with large size and irregular shape were independent predictors for piecemeal resection, long operation time and intraoperative bleeding.

Submucosal tumors (SMTs) from the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) are much more difficult to resect because of the sharp angle and narrow lumen of the EGJ. SMTs originating from the muscularis propria (MP) in the EGJ, especially those that grow extraluminally and adhere closely to the serosa, make endoscopic resection even more difficult.

Endoscopic resection approaches, including endoscopic submucosal dissection, submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection and endoscopic full-thickness resection, have been widely used for the treatment of SMTs from the MP layer at the EGJ. Only limited studies have demonstrated the predictors associated with the difficulty of endoscopic resection.

The aim of this study was to investigate the predictors of difficult endoscopic resection for SMTs from the MP layer at the EGJ.

A total of 90 patients with SMTs from the MP layer at the EGJ were included in the present study. Difficulty of endoscopic resection is measured by a long procedure time, failure of en bloc resection and intraoperative bleeding. Clinicopathological, endoscopic and follow-up data were collected and analyzed. Statistical analysis of independent risks for piecemeal resection, long operative time, and intraoperative bleeding were assessed using univariate and multivariate analyses.

No adverse events that required therapeutic intervention occurred during or after the procedures. The surgical approach had no significant correlation with en bloc resection, long operative time or intraoperative bleeding. Large tumor size (≥ 30 mm) and irregular tumor shape were independent predictors for piecemeal resection (OR: 7.346, P = 0.032 and OR: 18.004, P = 0.029, respectively), long operative time (≥ 60 min) (OR: 47.330, P =0.000 and OR: 6.863, P = 0.034, respectively) and intraoperative bleeding (OR: 20.631, P = 0.002 and OR: 19.020, P = 0.021, respectively).

Endoscopic resection is an effective treatment for SMTs in the MP layer at the EGJ. Tumors with large size and irregular shape were independent predictors for difficult endoscopic resection.

The current study may provide a useful reference for operators during endoscopic resection of SMTs originating from the MP layer at the EGJ in the future.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chiba H, Japan; Osawa S, Japan; Yoshida A, Japan S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Stein HJ, Feith M, Siewert JR. Cancer of the esophagogastric junction. Surg Oncol. 2000;9:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ponsaing LG, Kiss K, Hansen MB. Classification of submucosal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3311-3315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nishida T, Hirota S, Yanagisawa A, Sugino Y, Minami M, Yamamura Y, Otani Y, Shimada Y, Takahashi F, Kubota T; GIST Guideline Subcommittee. Clinical practice guidelines for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in Japan: English version. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:416-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee IL, Lin PY, Tung SY, Shen CH, Wei KL, Wu CS. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of intraluminal gastric subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1024-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Park JJ. Long-Term Outcomes after Endoscopic Treatment of Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Clin Endosc. 2016;49:232-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen T, Lin ZW, Zhang YQ, Chen WF, Zhong YS, Wang Q, Yao LQ, Zhou PH, Xu MD. Submucosal Tunneling Endoscopic Resection vs Thoracoscopic Enucleation for Large Submucosal Tumors in the Esophagus and the Esophagogastric Junction. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:806-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Peng W, Tan S, Huang S, Ren Y, Li H, Peng Y, Fu X, Tang X. Efficacy and safety of submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors with more than 1-year' follow-up: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:397-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hwang JC, Kim JH, Shin SJ, Cheong JY, Lee KM, Yoo BM, Lee KJ, Cho SW. Endoscopic resection for the treatment of gastric subepithelial tumors originated from the muscularis propria layer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:1281-1286. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Xu HW, Zhao Q, Yu SX, Jiang Y, Hao JH, Li B. Comparison of different endoscopic resection techniques for submucosal tumors originating from muscularis propria at the esophagogastric junction. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang Z, Zheng Z, Wang T, Wang X, Cao Y, Wang Y, Wang B. Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection of large submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer in the esophagus and gastric cardia. Z Gastroenterol. 2019;57:952-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li B, Liu J, Lu Y, Hao J, Liu H, Jiang J, Jiang Y, Qin C, Xu H. Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for tumors of the esophagogastric junction. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2016;25:141-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen T, Zhou PH, Chu Y, Zhang YQ, Chen WF, Ji Y, Yao LQ, Xu MD. Long-term Outcomes of Submucosal Tunneling Endoscopic Resection for Upper Gastrointestinal Submucosal Tumors. Ann Surg. 2017;265:363-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jeon SW, Jung MK, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH. Predictors of immediate bleeding during endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric lesions. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1974-1979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xu MD, Cai MY, Zhou PH, Qin XY, Zhong YS, Chen WF, Hu JW, Zhang YQ, Ma LL, Qin WZ, Yao LQ. Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection: a new technique for treating upper GI submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:195-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li ZS, Li Q. [The latest 2010 WHO classification of tumors of digestive system]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2011;40:351-354. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Mao XL, Ye LP, Zheng HH, Zhou XB, Zhu LH, Zhang Y. Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection using methylene-blue guidance for cardial subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Song S, Feng M, Zhou H, Liu M, Sun M. Submucosal Tunneling Endoscopic Resection for Large and Irregular Submucosal Tumors Originating from Muscularis Propria Layer in Upper Gastrointestinal Tract. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28:1364-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li Z, Gao Y, Chai N, Xiong Y, Ma L, Zhang W, Du C, Linghu E. Effect of submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for submucosal tumors at esophagogastric junction and risk factors for failure of en bloc resection. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:1326-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lv XH, Wang CH, Xie Y. Efficacy and safety of submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:49-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |