Published online Apr 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i4.370

Peer-review started: December 3, 2021

First decision: January 30, 2022

Revised: February 2, 2022

Accepted: March 26, 2022

Article in press: March 26, 2022

Published online: April 27, 2022

Processing time: 142 Days and 7.3 Hours

We read with interest the review by Teng et al, who summarized the current approach to the diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis (AA). Also, the article summarizes the clinical scoring systems very effectively. In one of the previous studies conducted by our research group, we showed that the use of the Alvarado score, ultrasound and C-reactive protein values in combination provides a safe confirmation or exclusion of the diagnosis of AA. Computed tomography is particularly sensitive in detecting periappendiceal abscess, peritonitis and gangrenous changes. Computed tomography is not a good diagnostic tool in pediatric patients because of the ionizing radiation it produces. Ultrasound is a valuable diagnostic tool to differentiate AA from lymphoid hyperplasia. Presence of fluid collection in the periappendiceal and lamina propria thickness less than 1 mm are the most effective parameters in differentiating appendicitis from lymphoid hyperplasia. Although AA is the most common cause of surgical acute abdomen, it remains an important diagnostic and clinical challenge. By combining clinical scoring systems, laboratory data and appropriate imaging methods, diagnostic accuracy and adherence to treatment can be increased. Lymphoid hyperplasia and perforated appendicitis present significant diagnostic challenges in children. Additional ultrasound findings are increasingly defined to differentiate AA from these conditions.

Core Tip: Despite the fact that acute appendicitis is the most common cause of acute abdomen, it remains a diagnostic and clinical challenge. When the ultrasound, Alvarado scoring and C-reactive protein are used in conjunction to diagnose acute appendicitis, the diagnosis can be safely confirmed or ruled out. Computed tomography scans are extremely sensitive in detecting complications from acute appendicitis. Computed tomography scans are especially effective at detecting periappendix abscesses, peritonitis and gangrenous changes. Because of the ionizing radiation it emits, computed tomography is not a good diagnostic tool in pediatric patients. In pediatric patients, ultrasound should be the preferred method.

- Citation: Aydın S, Karavas E, Şenbil DC. Imaging of acute appendicitis: Advances. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(4): 370-373

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i4/370.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i4.370

We read with interest the review by Teng et al[1], who summarized the current approach to the diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis (AA). Also, the article summarizes the clinical scoring systems very effectively.

In one of the published studies of our research group, we have shown that using the Alvarado score, ultrasound (US) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in combination enables the confirmation or rejection of AA safely[2]. The Alvarado scoring system is one of the most commonly used methods[1]. Even though the scoring system contains series of laboratory parameters, it does not contain CRP levels. Rather than using the Alvarado system or US alone, combining these methods with CRP levels will increase diagnostic accuracy.

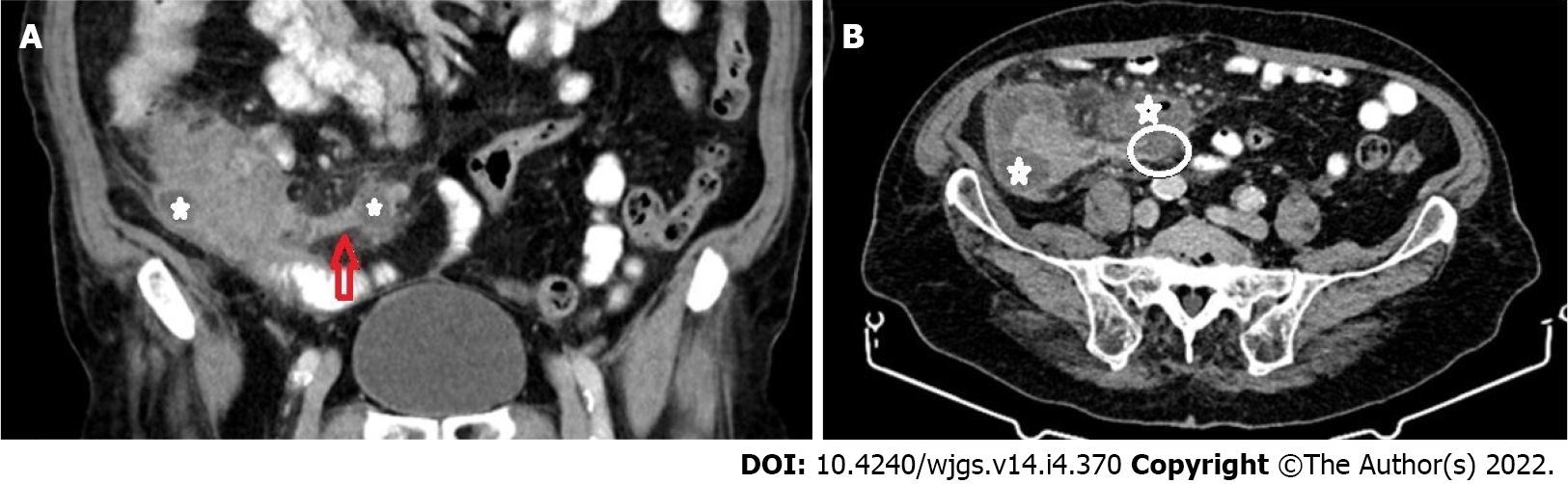

Teng et al[1] stated that computerized tomography scans have a well-established role in evaluating AA-related complications. Computed tomography is especially sensitive for detecting periappendiceal abscess, peritonitis and gangrenous changes[1] (Figure 1). Pediatric patients are more likely to develop perforated appendicitis. Imaging is critical in diagnosing perforated appendicitis; clinical differentiation can be challenging, especially in younger children. Computed tomography is not a good diagnostic tool in pediatric patients due to the ionizing radiation it produces. According to our results, US can also be used as an effective diagnostic tool for the detection of pediatric perforated appendicitis cases. The most valuable US parameters are the detection of loculated fluid in the periappendiceal area and fluid collection in all abdominal recesses. When these parameters are combined with CRP levels, diagnostic performance can be improved[3].

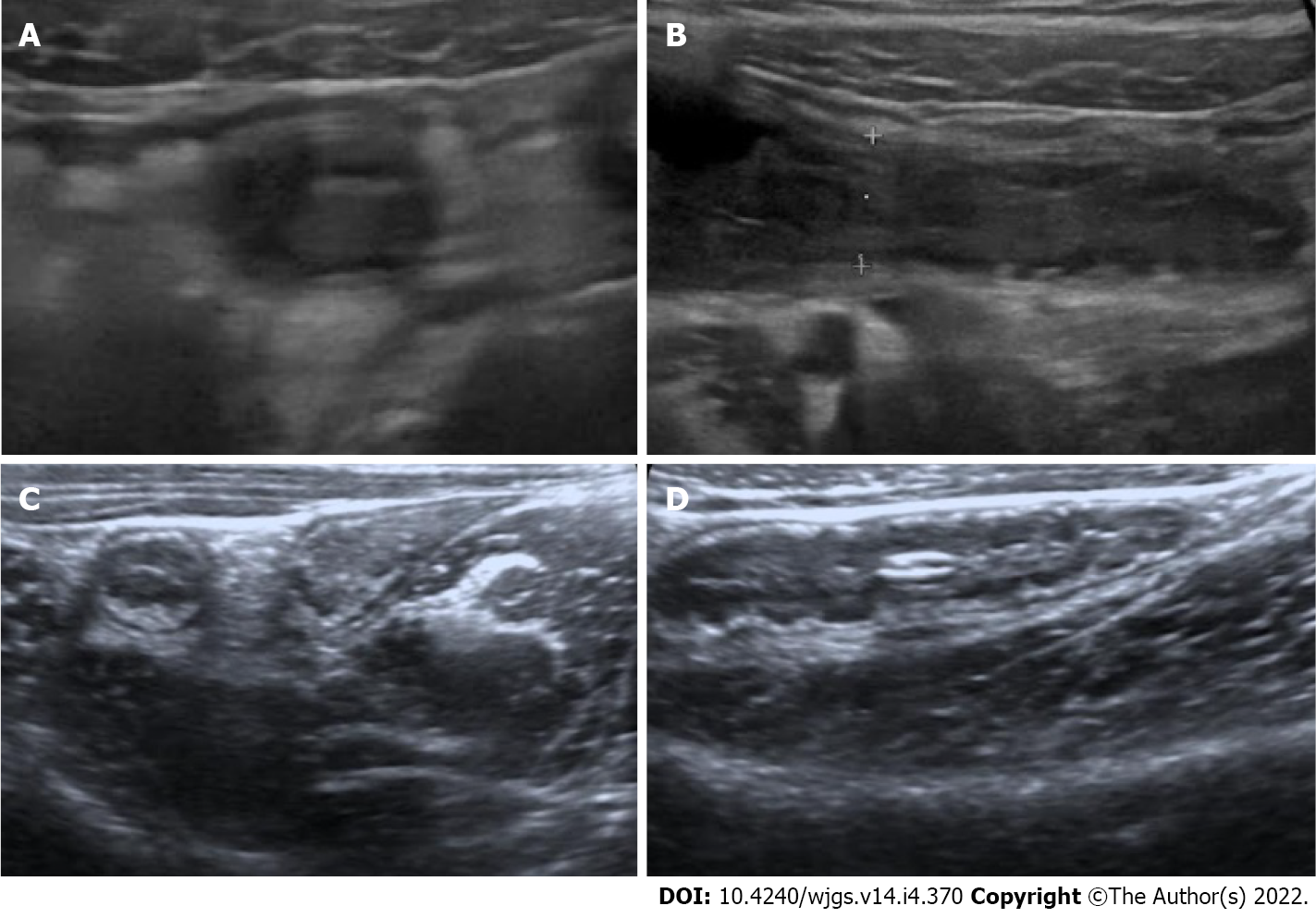

Teng et al[1] emphasized that AA occurs when the appendiceal orifice is obstructed (for example, by lymphoid hyperplasia or fecaliths), resulting in inflammation. We have demonstrated that, in addition to causing AA, lymphoid hyperplasia can serve as a significant mimicker of AA by forming an incompressible appendix larger than 6 mm in diameter, particularly in pediatric patients. US is a valuable diagnostic tool for differentiating AA from lymphoid hyperplasia. The presence of periappendiceal fluid collection and a lamina propria thickness of less than 1 mm are the most effective parameters for differentiating appendicitis from lymphoid hyperplasia[4] (Figure 2).

The portal vein can be affected from appendiceal inflammation, and thrombosis might occur[1]. In addition to complications, according to our data, portal vein hemodynamic changes can help to confirm AA diagnosis in children. In equivocal cases, detecting an increase in portal vein diameter and/or flow velocity may corroborate other clinical signs of AA[5].

To summarize, AA remains a significant diagnostic and clinical challenge despite being the most common cause of surgical acute abdomen. By combining clinical scoring systems, laboratory data and appropriate imaging methods, diagnostic accuracy and treatment adherence can be increased. Lymphoid hyperplasia and perforated appendicitis present significant diagnostic challenges in children. Additional US findings are increasingly being defined for the purpose of distinguishing AA from these entities.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abd EL hafez A, Egypt; Wichmann D, Germany S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Teng TZJ, Thong XR, Lau KY, Balasubramaniam S, Shelat VG. Acute appendicitis-advances and controversies. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;13:1293-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 2. | Aydin S, Fatihoglu E, Ramadan HS, Akhan B, Koseoglu EN. Alvarado score, ultrasound, and CRP: how to combine them for the most accurate acute appendicitis diagnosis. Iranian J Radi. 2017;14. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Aydin S, Fatihoğlu E. Perforated appendicitis: A sonographic diagnostic challenge. Ankara Eğitim ve Araştırma Hastanesi Tıp Dergisi. 2018;51:110-115. |

| 4. | Aydin S, Tek C, Ergun E, Kazci O, Kosar PN. Acute Appendicitis or Lymphoid Hyperplasia: How to Distinguish More Safely? Can Assoc Radiol J. 2019;70:354-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aydin S, Ucan B. Pediatric acute appendicitis: Searching the diagnosis in portal vein. Ultrasound. 2020;28:174-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |