Published online Feb 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i2.187

Peer-review started: September 1, 2020

First decision: October 23, 2020

Revised: November 20, 2020

Accepted: December 23, 2020

Article in press: December 23, 2020

Published online: February 27, 2021

Processing time: 156 Days and 8.4 Hours

Perianal fistulae strongly impact on quality of life of affected patients.

To challenge and novel minimally invasive treatment options are needed.

Patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) in remission and patients without inflammatory bowel disease (non-IBD patients) were treated with fistulodesis, a method including curettage of fistula tract, flushing with acetylcysteine and doxycycline, Z-suture of the inner fistula opening, fibrin glue instillation, and Z-suture of the outer fistula opening followed by post-operative antibiotic prophylaxis with ciprofloxacin and metronidazole for two weeks. Patients with a maximum of 2 fistula openings and no clinical or endosonographic signs of a complicated fistula were included. The primary end point was fistula healing, defined as macroscopic and clinical fistula closure and lack of patient reported fistula symptoms at 24 wk.

Fistulodesis was performed in 17 non-IBD and 3 CD patients, with a total of 22 fistulae. After 24 wk, all fistulae were healed in 4 non-IBD and 2 CD patients (overall 30%) and fistula remained closed until the end of follow-up at 10-25 mo. In a secondary per-fistula analysis, 7 out of 22 fistulae (32%) were closed. Perianal disease activity index (PDAI) improved in patients with fistula healing. Low PDAI was associated with favorable outcome (P = 0.0013). No serious adverse events were observed.

Fistulodesis is feasible and safe for perianal fistula closure. Overall success rates is at 30% comparable to other similar techniques. A trend for better outcomes in patients with low PDAI needs to be confirmed.

Core Tip: Perianal fistulae strongly impact on quality of life of affected patients. Despite various treatment options clinical care of fistula patients remains a challenge and novel minimally invasive treatment options are needed. Fistulodesis is feasible and safe for perianal fistula closure. Overall success rates is at 30% comparable to other similar techniques. A trend for better outcomes in patients with low perianal disease activity index needs to be confirmed.

- Citation: Villiger R, Cabalzar-Wondberg D, Zeller D, Frei P, Biedermann L, Schneider C, Scharl M, Rogler G, Turina M, Rickenbacher A, Misselwitz B. Perianal fistulodesis – A pilot study of a novel minimally invasive surgical and medical approach for closure of perianal fistulae. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(2): 187-197

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i2/187.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i2.187

Symptoms of perianal fistulae include secretion of mucus, blood, pus and/or stool as well as pain, fecal incontinence and sexual dysfunction[1], leading to a pronounced decrease in the quality of life[2]. Most perianal fistulae occur due to obstruction of anal glands and an acute perianal abscess can transform into a fistula; vice versa, fistulae can be complicated by perianal abscesses in case of congestion of secretions[3]. Numerous surgical therapeutic options for perianal fistulae exist, all are limited by low to moderate success rates and frequent relapses[4-6].

Perianal fistulae are also a frequent problem in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), a chronic, immune-mediated disease of the intestinal tract[7]. Multiple medical, surgical and combined treatment options exist[8], however, CD fistulae still present a significant clinical challenge for patients and physicians alike[9,10]. Therapeutic success for long-term fistula healing in CD patients is unsatisfying with healing rates reaching 50% at most and even after initial success, CD fistulae frequently relapse[11,12]. This might also be related to a different pathogenesis of CD fistula compared to non-CD fistulas. Mesenchymal stem cells might significantly improve treatment success[13], but the treatment is very cost intensive and long-term safety data are lacking.

Fibrin glue instillation, leading to formation of a fibrin clot and mechanical sealing of the fistula tract has been introduced as a fistula treatment two decades ago[14,15]. Fibrin application for perianal fistulae is well-tolerated[16] and even in case of treatment failure, there is no evidence for a negative impact on future treatment attempts[17]. Unfortunately, success rates vary widely[16] and in an illustrative study, a 38% success rate in CD patients has been described[18]. Further modifications to improve success rates of fibrin glue treatment would be desirable.

In this study we tested the fistulodesis concept, comprising surgical curettage, flushing of the fistula tract with acetylcysteine and doxycycline, surgical closure of the fistula openings and closure of the fistula tract with fibrin glue followed by antibiotic treatment for ten days post-operatively. Here we report the feasibility and success rates of fistulodesis and identified predictors for success, possibly enabling improvements of our procedure.

The fistulodesis pilot study is an open label, prospective and interventional study, including two centers. The study included patients with perianal fistulae, divided into an IBD and a non-IBD cohort, initially aiming to include 20 patients into each group. After two years and slow recruitment in the CD arm of the study, we decided to interrupt the study and report the results.

Patients were recruited between June 2017 and November 2018. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Signed written informed consent; (2) ≥ 18 years of age; (3) Persistent perianal fistula for ≥ 3 mo; (4) Planned examination under anesthesia; (5) Exclusion of pregnancy via a prior urine test in females of childbearing potential and willingness to use effective contraception during study participation; and (6) no breastfeeding. In addition, the following exclusion criteria applied: (1) > 2 external fistula openings; (2) A history of irradiation of the anorectum; (3) Clinical signs and symptoms of an acute perianal abscess; (4) Perianal surgery during the last four weeks; (5) Known allergy or non-tolerance against one or more of the used medical products; (6) Current antibiotic therapy; (7) Diagnosis of another severe medical, surgical or psychiatric condition requiring active management; (8) Current participation in another study potentially interfering with study procedures; and (9) inability to follow study procedures.

For CD patients, additional inclusion criteria applied: (1) Diagnosis of CD established for at least three months; (2) CD in remission [defined as a Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) of ≤ 4]. CD patients were excluded in case of (1) active inflammation in the rectum (outside the fistula); (2) Systemic intake of steroid-medication in a dose of > 20 mg prednisone or equivalent currently or during the last four weeks; or (3) the use of a newly prescribed immunosuppressant medication for CD including biologics within the last four weeks before inclusion into the study (changes in 5-aminosalicylic acid or rectal treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid or budesonide were permitted).

All patient signed a written informed consent, patients were provisionally included into our study and baseline clinical assessment was performed, followed by clinical examination and evaluation of perianal fistula under anesthesia. If necessary, clinical examination was supplemented by endosonographic ultrasound. Additional criteria to exclude patients with an abscess or complex fistula tract (and low chances of fistula healing) or patients with a superficial fistula (who would better be served by sphincterotomy) were applied during examination under anesthesia. The following intraoperative exclusion criteria were used: Fistula system (1) not entirely accessible by curettage or brushing due to its shape; (2) with large pocket ≥ 1 cm suggestive for an abscess; (3) with a horseshoe-shape; or (4) a superficial trajectory of the fistula tract involving < 30% or < 10% of the anal sphincter in males and females, respectively. Only if none of these exclusion criteria applied, a patient was ultimately included into our study.

If during examination under anesthesia no exclusion criterion was met, surgical fistulodesis was performed. Fistulodesis comprises the surgical removal of debris via curettage or brushing and a mini-excision of the inner fistula opening, followed by flushing of the fistula tract with acetylcysteine 100 mg/mL (Zambon, Switzerland) and doxycycline 20 mg/mL (Pfizer, maximal dosage 200 mg per treatment). The rational for using acetylcysteine was to remove mucus and the biofilm that covers the fistula tract[19,20]. A single case report described cure of a gastro-pancreatic fistula due to intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm using prolonged irrigation with acetylcysteine[21]. Doxycycline was chosen to induce fibrin secretion and therefore agglutination of the fistula tract similar to its use in pleurodesis[22-25] and closure of lymphatic fistulae[26,27]. Surgical closure of both fistula openings was achieved by a Z-suture with multifilament absorbable suture material (Vicryl 3-0). Before completely closing the outer fistula opening the fistula tract was adhered with fibrin glue

After fistulodesis, patients were examined following a pre-defined schedule to evaluate fistula healing and exclude adverse events at week 1, 2, 4, 12 and 24 after the intervention. Fistula symptoms and overall patient wellbeing after the fistulodesis procedure was assessed by phone call 1-2 years after treatment.

Healing of all perianal fistulae at 24 wk was the primary outcome of our study. Fistula healing was defined by the presence of all the following criteria, (1) no secretion from any fistula during the last two weeks as reported by the patient; (2) no secretion upon gentle compression of the fistula tract; (3) macroscopic closure of the outer opening of the fistula tract upon inspection; and (4) no pain at the site of the former fistula opening during gentle palpation.

We also assessed several secondary outcomes: (1) Safety of the fistulodesis procedure. (2) Quality of life, using the patient-filled German version of the IBD-Q questionnaire at enrolment and 24 wk after intervention[28]. (3) Fistula activity: At every visit (screening, weeks 1, 2, 4, 12 and 24 after intervention) the fistula tract was clinically examined. The number of fistula openings with and without secretion upon palpation was recorded to assess fistula drainage. The patients were asked to quantify local pain sensation (visual analogue scale, VAS 0-10; 0: none) and secretion of the fistula, both over the course of the past two weeks (0: no secretion, 1: less than once weekly, 2: weekly, 3: repeatedly in one week, 4: daily, 5: several times per day). Fistula closure was evaluated (criteria stated above) at every visit. (4) Overall perianal symptoms were evaluated by the perianal disease activity index (PDAI)[29] at weeks 4, 12 and 24. (5) CD disease activity was assessed by the HBI[30] and was determined at the same time points (PDAI and HBI were filled by physicians). (6) We also analyzed fistula healing in a per-fistula analysis. (7) Healing of fistula was also assessed at 24 wk in an abbreviated procedure via telephone interview. And (8) Primary and secondary outcomes were compared in patients with and without IBD.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (Version 8.2.1). Statistical comparisons were performed using non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney or Wilcoxon test) or Fisher’s exact test, whatever appropriate. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Zurich County (KEK-ZH-NR. 2016-01310) on 1st of February 2017. Application of acetylcysteine and doxycycline into the fistula tract was approved by the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products (Swissmedic). The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03322488). Study procedures were performed following principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki 2013.

Overall, 29 patients with perianal fistulae were recruited, 24 non-IBD patients and five patients with CD. One patient subsequently withdrew informed consent. Upon endoanal ultrasound and fistula examination in anesthesia, 8 patients were excluded (2 patients with minimal involvement of anal sphincter apparatus were treated with fistulotomy, in 2 patients the internal diameter was judged to be too large for feasible fistula closure and seton drainage was performed, in 2 other patients an abscess was identified and treated with seton drainage in 1 and fistula excision in the other patient; in 1 other patient a curved and branched fistulae tract with two openings would have been inaccessible to curettage prompting treatment with ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) and seton drainage, respectively, in 1 patient, spontaneous fistula cleavage was observed and no treatment was performed). Overall, 20 patients were finally included into the study and treated with fistulodesis (17 non-IBD and 3 CD patients).

Our study cohort comprised a mixed population of male and female patients with mild to moderate fistula disease (range of PDAI 3-14). One CD patient was under long-term treatment with adalimumab, 1 additional patient was treated with a combination of infliximab and vedolizumab. All other patients did not use any immunomodulatory medication. In total, 18 patients had undergone previous fistula surgery, while 2 patients had had no prior fistula treatment. The number of interventions ranged from 1-10. In 8 out of 18 patients, surgical treatment was limited to seton administration on at least one occasion. Another 10 patients had been treated with one or more procedure aiming for definitive fistula closure, such as mucosal advancement flap: 4 interventions, fistulectomy: 4, plug insertion: 4, fistulotomy: 3, LIFT: 3, over the scope clip: 1, video-assisted anal fistula treatment: 1 and an unspecified procedure: 1, with or without previous seton conditioning. CD patients reported longer duration of fistulizing disease but higher quality of life at screening than non-IBD patients (P = 0.033, Table 1).

| Characteristics | Non-IBD patients, n = 17 | Patients with CD, n = 3 | P value |

| Female: n (%); Male: n (%) | 8 (47%); 9 (53%) | 2 (66%); 1 (33%) | > 0.9999 (NS) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR), range | 26 (21-30); Range: 20-38 | 23 (20h28); Range: 20-28 | 0.5632 (NS) |

| Age (yr), median (IQR), range | 45 (39-52.2); Range: 32-76 | 34 (25-52); Range: 25-52 | 0.3114 (NS) |

| Smokers: n (%); Pack years; median (IQR), range | 4 (24%)1; 0 (0-12.5)2; Range: 0-30 | 1 (33%); 0.25 (0-10); Range: 0-10 | 0.3333 (NS); 0.7911 (NS) |

| Years from fistula onset until fistulodesis median (IQR), range | 1 (0-2); Range: 0-12 | 3 (2-7); Range: 2-7 | 0.0386 |

| Previous fistula operations median (IQR), range | 1 (1-3); Range: 0-10 | 4 (2-8); Range: 2-8 | 0.1219 (NS) |

| IBD-Q score at screening median (IQR), range | 167.5 (144.5-199.3)3; Range: 110.5-217 | 215.5 (213-218)4; Range: 213-218 | 0.0333 |

| PDAI at screening median (IQR), range | 6 (5-8); Range: 3-141 | 5 (4-7); Range: 4-7 | 0.4334 (NS) |

| HBI at screening median (IQR), range | Not determined | 0 (0-2); Range: 0-2 | |

| Pre-operative local pain median (IQR), range | 1 (1-2.8); Range: 0-101 | 2 (1-5); Range: 1-5 | 0.4964 (NS) |

| Pre-operative secretions median (IQR), range | 4 (3-5); Range: 0-51 | 4 (4-5); Range: 4-5 | 0.8720 (NS) |

| Distance outer lumen to dentate line (cm) median (IQR), range | 2 (1.4-3.1); Range: 1-41 | 1 (1-2); Range: 1-2 | 0.1714 (NS) |

| Distance inner lumen to dentate line (cm) median (IQR), range | 0 (0-0.5); Range: 0-21 | 0.5 (0-1.5); Range: 0-1.5 | 0.3842 (NS) |

| Length of fistula tract (cm) median (IQR), range | 3.8 (2.7-4.9); Range: 1.5-61 | 2.5 (2-5); Range: 2-5 | 0.5549 (NS) |

| Sphincter involvement (%) mean (IQR), range | 50 (40-68.3); Range: 25-801 | 55 (20-90); Range: 20-90 | > 0.9999 (NS) |

| Fistula closure 24 wk after fistulodesis; n (%) | 5 (26%)5 | 2 (66%) | 0.3333 (NS) |

Fistulodesis was performed in 20 patients with a total of 22 fistulae, as two non-IBD patients initially presented with two separate fistulae. Our definition of fistula healing comprised the closure of all fistula openings, lack of fistula symptoms and lack of clinical signs of fistula activity (see methods). Fistula healing criteria at 24 wk were met in a total of 6 out of 20 patients, corresponding to a success rate of 30%. When all 22 treated fistulae were evaluated individually in a per-fistula analysis, a slightly higher healing rate was calculated (7 out of 22 fistulae, 36%).

Comparing CD vs non-IBD patients, fistula closure was effective in 2 out of 3 CD patients (66%) vs 5 out of 17 non-IBD patients (29%). However, due to small numbers in the CD group, robust comparison of CD and non-IBD patients is not possible.

Time to fistula recurrence varied considerably, from one week up to 12 wk post intervention. Most recurring fistulae (10 out of 14, 71%) reopened or developed a new outer fistula opening after 4 wk (Supplementary Figure 1).

Of the 14 patients with unsuccessful fistulodesis, 9 underwent 20 additional fistula surgery with the intention of fistula closure outside of this study (mucosal advancement flap: 4, plugs: 4, fistulectomy: 4, fistulotomy: 3, LIFT: 3, over the scope clip: 1, video-assisted anal fistula treatment: 1). Out of these 9 patients, the fistula of 5 patients healed after one additional surgery following failed fistulodesis, and in 3 patients after two additional surgeries. In 1 patient results of the latest surgery is pending, another patient had a seton administered for fistula conditioning and 1 patient had no surgical intervention after participation in this study. In 4 patients, no follow-up information is available.

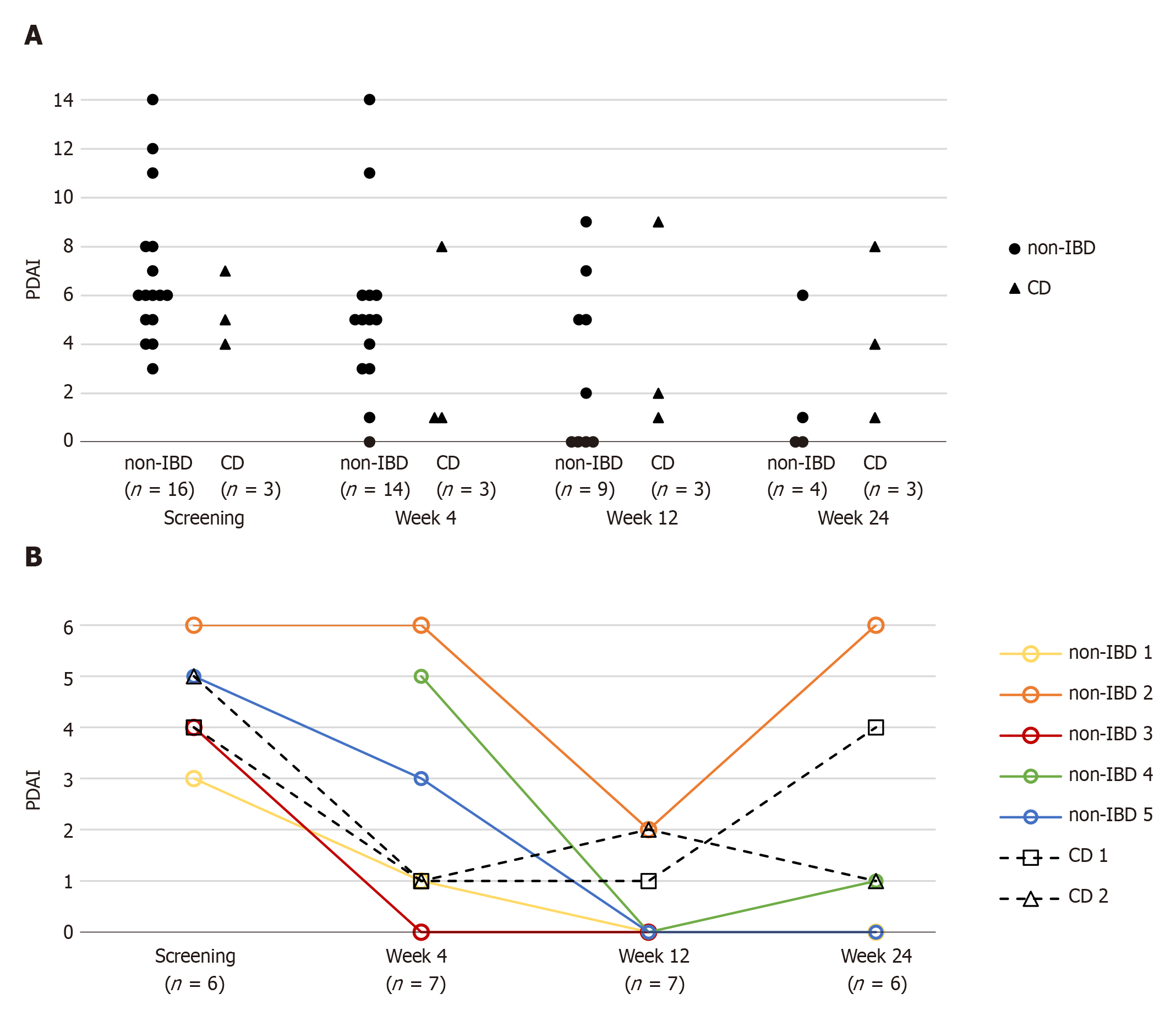

Overall, fistulodesis did not significantly affect PDAI in our patient cohort (Figure 1). Even in patients with successful closure of at least 1 fistula opening, trends in PDAI were variable (PDAI for 5 patients available): PDAI was 0 for a single patient; In 2 patients, PDAI was 1 with remaining minimal disease activity due to anal fissure and minimal anal mucous secretion, respectively. Two patients did not show any improvement in PDAI. This was one non-IBD patient with two fistulae at enrollment success for only 1 fistula and one CD patient, who, at 24 wk post-interventional, developed a new fistula (see below).

Similarly, fistulodesis treatment did neither reduce patient-reported fistula secretion or local pain (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). However, in the subgroup of patients with closure of at least 1 fistula, patient-reported secretion significantly diminished at 24 wk (P = 0.03, Supplementary Figures 2B) and favorable trends for local pain in this group were observed (Supplementary Figure 3B).

Quality of life was evaluated in 14/17 non-IBD patients at enrolment; However, only data from 5 patients were available at 24 wk. We note favorable trends in 2 non-IBD patients upon successful fistulodesis but no significant effects (Supplementary Figure 4).

All six patients with at least one successful fistula closure were contacted by phone between 12 to 30 mo after fistulodesis. Five patients were entirely free of symptoms without pain, secretion, local symptoms or limitations in sexual behavior and without further fistula interventions consistent with closure of all 6 fistulae. One patient with successful closure of 1 fistula and recurrence of the other fistula 12 wk after fistulodesis reported persistent closure of the fistula and persistent symptoms from the other (pain and secretions) and no change compared to 24 wk. One patient reported new secretion but no recurrent fistula was detected during examination under anesthesia.

Patients with successful fistulodesis had lower pre-operative PDAI (4 vs 6.5, P = 0.0013) than patients without treatment success (Supplementary Table 1). When analyzed individually, the PDAI items “pain” and “secretion” also differed according to treatment success, but no significant differences were observed. Treatment success also tended to be higher in males (6/7 with successful fistulodesis vs 4/13 without success, P = 0.057). Patients with treatment success also tended to be younger (ns), but with a higher number of previous surgical procedures. However, most additional patient characteristics did not differ between patients with and without treatment success, especially no anatomic predictor for success could be identified (Supplementary Table 1).

Adverse events occurred in 5 patients (Table 2). One patient developed a new fistula at a distinct location and without any direct connection to the fistula tract of the first fistula at 24 wk after the intervention. The fistula was also successfully treated with fistulodesis, outside the study protocol. This fistula was considered due to progressive CD and unrelated to fistulodesis. Another patient developed an abscess at a different location from the initial fistula which was successfully treated with abscess incision. In one patient, exacerbation of pre-existing hypo-regeneratory anemia was described and treated conservatively. In one patient, an anal fissure was reported and treated conservatively. Besides the anal fissure, a relationship of the observed side effects to study procedures seems unlikely. Therefore, we regard fistulodesis as a safe and well-tolerated procedure.

| Side effects of treatment | Non-IBD patients, n = 17 | Patients with CD, n = 3 | Related to study procedures |

| Fistula recurrence | 13 | 1 | Yes |

| New fistula (at a separate site from initial fistula) | 0 | 1 | Unlikely |

| Perianal abscess (at a separate site from initial fistula) | 1 | 0 | Unlikely |

| Anemia | 1 | 0 | Highly unlikely |

| Anal fissure | x | x | Possible |

In our study, we aimed to improve success rates of fibrin glue treatment by combining it with curettage and cleaning of the fistula tract, surgical closure and antibiotic treatment as a fistulodesis procedure. Previous studies with fibrin glue application had shown limited success between 25%-94%[18,31,32]. Despite our concept of combining minimally invasive surgical and medical treatments, our success rate remained modest at 30% after 24 wk. Direct comparison of studies is difficult due to different study designs; For instance, repeated fibrin glue injection was performed in some but not all studies. However, in past studies, even repeated glue application was not successful in all studies with CD patients[33]. In the largest study so far with fibrin glue in 34 CD patients with perianal disease, a success rate of 38% could be achieved[18] but the early primary endpoint at 8 wk has been criticized[34].

Despite our comprehensive approach upon fistulodesis treatment, our modest success rate of 30% remains at the lower end of success rates reported in other studies. However, local symptoms improved in patients upon successful fistulodesis, indicated by improvements in PDAI. Long-term data in patients with successful fistulodesis suggest, that therapy effects at 24 wk remains stable at least for the next 6-12 mo.

Treatment success tended to be higher in CD patients than in non-IBD patients, even though no significance was achieved due to inadequate power. Future studies are needed to show, whether high success rates in IBD patients can be reproduced. Further, success rates tended to be higher in male patients. A high PDAI was the only significant negative predictor for treatment success identified in our study, pointing to detrimental effects of local inflammation on fistula healing.

Several methods for fistula treatment have been advanced but no superior method suitable for all indications has been identified. Fistulotomy is the method of choice for very superficial fistula[35,36]; However, incontinence rates would be unacceptable for fistula with profound involvement of the sphincter apparatus. Accordingly, two patients with only minor involvement of the anal sphincter (< 30% in males, < 10% in females) were excluded from our study and treated with fistulotomy. Sphincter sparing techniques include mucosal advancement flap and the LIFT approach are associated with success rates of 40%-95%[31]. However, even with proper application, side effects include minor disorders of continence in 5%-50% of cases[31]. In our study, fistulodesis was a well-tolerated procedure, in line with the excellent safety profile of fibrin glue treatment and these methods might be considered for patients with a low tolerance of side effects.

Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation is a new and innovative treatment principle and potentially a shift in paradigms. In a randomized controlled trial success rates of 56.3% vs 38.6% in controls were observed[37,38]. Garcia-Olmo et al[39] observed high healing rates of 71% in complex fistulae when adipose-derived stem cells and fibrin glue were instilled into the fistula tract compared to 16% for simple fibrin glue administration and similar healing rates were observed in non-IBD and CD cohorts[39]. Therefore, stand-alone human mesenchymal stem cell therapy seems effective and safe in the treatment of refractory perianal fistulae in CD patients but needs further investigation[40,41]. Since long-term effects of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation remain unknown and treatment is expensive, the need for minimally invasive and economic therapies remains.

Strengths of our study include a robust composite primary endpoint derived from clinical examination and patient reported outcomes which would be meaningful in clinical practice. Follow-up time was adequately long to exclude transient treatment effects. Further, our non-IBD cohort was sufficiently large, comprising 17 patients with a broad variety in epidemiological characteristics, as would be found in a real-world setting. The main limitation of our study is the small number of CD patients, limiting evaluation and statistical comparison of CD with non-IBD patients. Furthermore, data acquisition during follow-up was occasionally incomplete and a considerable amount of data for some secondary endpoints including quality of life are missing.

In summary, our study suggests fistulodesis to be a minimally invasive method with a low risk for complications but modest overall success rates. Selected patients with low tolerance for side effects might benefit from this therapeutic approach after individual assessment and discussion. According to our results, CD patients with mild symptoms (low PDAI) might benefit from fistulodesis; However, this needs to be confirmed by future studies.

Perianal fistulae are frequent, yet poorly understood conditions occurring in otherwise healthy individuals, as well as in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD). A wide range of surgical treatment options including fibrin glue instillation exist, nevertheless, healing rates vary largely and are unsatisfying especially in patients with CD. There is an ongoing need to establish safe, economic and well-tolerated but highly effective treatment options for perianal fistulae.

To develop an effective minimally invasive fistula treatment.

To establish safety and effectiveness of fistulodesis, a combined medical-surgical treatment option for perianal fistulae.

Non-CD and CD patients with perianal fistula were treated with fistulodesis in an open label uncontrolled study. Patients with complex fistula, > 2 fistula openings and active CD were excluded. Fistulodesis comprises flushing of the fistula tract with acetylcysteine and doxycycline, instillation of fibrin glue into the fistula tract and surgical closure of the internal opening. The primary endpoint of our study was fistula healing, defined as macroscopic and clinical fistula closure and lack of patient reported fistula symptoms at 24 wk.

Fistulodesis was tested in 17 non-CD and 3 CD patients. Fistula healing was observed in 30% of patients after 24 wk and healed fistulae remained closed for more than one year after treatment. No severe side effects were observed. Low clinical fistula activity with a low perianal disease activity index was associated with fistula healing.

Fistulodesis is a minimally invasive and safe treatment option for perianal fistulae with limited effectiveness, comparable to other minimally invasive treatment options.

Effectiveness of fistulodesis in CD patients could be tested in a future dedicated clinical trial. Our stringent composite primary endpoint of fistula healing, could be useful in future clinical studies for fistula treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Switzerland

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chapman BC S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Leenhardt R, Rivière P, Papazian P, Nion-Larmurier I, Girard G, Laharie D, Marteau P. Sexual health and fertility for individuals with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:5423-5433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Owen HA, Buchanan GN, Schizas A, Cohen R, Williams AB. Quality of life with anal fistula. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98:334-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dudukgian H, Abcarian H. Why do we have so much trouble treating anal fistula? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3292-3296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | de Groof EJ, Cabral VN, Buskens CJ, Morton DG, Hahnloser D, Bemelman WA; research committee of the European Society of Coloproctology. Systematic review of evidence and consensus on perianal fistula: an analysis of national and international guidelines. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:O119-O134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ommer A, Herold A, Berg E, Fürst A, Sailer M, Schiedeck T. German S3 guideline: anal abscess. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:831-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee MJ, Parker CE, Taylor SR, Guizzetti L, Feagan BG, Lobo AJ, Jairath V. Efficacy of Medical Therapies for Fistulizing Crohn's Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1879-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Panes J, Reinisch W, Rupniewska E, Khan S, Forns J, Khalid JM, Bojic D, Patel H. Burden and outcomes for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: Systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4821-4834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yassin NA, Askari A, Warusavitarne J, Faiz OD, Athanasiou T, Phillips RK, Hart AL. Systematic review: the combined surgical and medical treatment of fistulising perianal Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:741-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee MJ, Brown SR, Fearnhead NS, Hart A, Lobo AJ; PCD Collaborators. How are we managing fistulating perianal Crohn's disease? Frontline Gastroenterol. 2018;9:16-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gecse KB, Sebastian S, Hertogh Gd, Yassin NA, Kotze PG, Reinisch W, Spinelli A, Koutroubakis IE, Katsanos KH, Hart A, van den Brink GR, Rogler G, Bemelman WA. Results of the Fifth Scientific Workshop of the ECCO [II]: Clinical Aspects of Perianal Fistulising Crohn's Disease-the Unmet Needs. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:758-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lopez N, Ramamoorthy S, Sandborn WJ. Recent advances in the management of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease: lessons for the clinic. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:563-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kotze PG, Shen B, Lightner A, Yamamoto T, Spinelli A, Ghosh S, Panaccione R. Modern management of perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: future directions. Gut. 2018;67:1181-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ciccocioppo R, Klersy C, Leffler DA, Rogers R, Bennett D, Corazza GR. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Safety and efficacy of local injections of mesenchymal stem cells in perianal fistulas. JGH Open. 2019;3:249-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Abel ME, Chiu YS, Russell TR, Volpe PA. Autologous fibrin glue in the treatment of rectovaginal and complex fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:447-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hjortrup A, Moesgaard F, Kjaergård J. Fibrin adhesive in the treatment of perineal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:752-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jacob TJ, Perakath B, Keighley MR. Surgical intervention for anorectal fistula. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010: CD006319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hammond TM, Grahn MF, Lunniss PJ. Fibrin glue in the management of anal fistulae. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:308-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Grimaud JC, Munoz-Bongrand N, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L, Sénéjoux A, Vitton V, Gambiez L, Flourié B, Hébuterne X, Louis E, Coffin B, De Parades V, Savoye G, Soulé JC, Bouhnik Y, Colombel JF, Contou JF, François Y, Mary JY, Lémann M; Groupe d'Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif. Fibrin glue is effective healing perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2010; 138: 2275-2281, 2281. e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Banerjee S, McCormack S. Acetylcysteine for Patients Requiring Mucous Secretion Clearance: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Safety [Internet]. 2019. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Rubin BK. Mucolytics, expectorants, and mucokinetic medications. Respir Care. 2007;52:859-865. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Hong MY, Yu DW, Hong SG. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the bile duct with gastric and duodenal fistulas. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Park EH, Kim JH, Yee J, Chung JE, Seong JM, La HO, Gwak HS. Comparisons of doxycycline solution with talc slurry for chemical pleurodesis and risk factors for recurrence in South Korean patients with spontaneous pneumothorax. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2019;26:275-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rafiei R, Yazdani B, Ranjbar SM, Torabi Z, Asgary S, Najafi S, Keshvari M. Long-term results of pleurodesis in malignant pleural effusions: Doxycycline vs Bleomycin. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Porcel JM, Salud A, Nabal M, Vives M, Esquerda A, Rodríguez-Panadero F. Rapid pleurodesis with doxycycline through a small-bore catheter for the treatment of metastatic malignant effusions. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:475-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tan C, Sedrakyan A, Browne J, Swift S, Treasure T. The evidence on the effectiveness of management for malignant pleural effusion: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:829-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hackert T, Werner J, Loos M, Büchler MW, Weitz J. Successful doxycycline treatment of lymphatic fistulas: report of five cases and review of the literature. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:435-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cnotliwy M, Gutowski P, Petriczko W, Turowski R. Doxycycline treatment of groin lymphatic fistulae following arterial reconstruction procedures. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;21:469-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Janke KH, Klump B, Steder-Neukamm U, Hoffmann J, Häuser W. [Validation of the German version of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (Competence Network IBD, IBDQ-D)]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2006;56:291-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Irvine EJ. Usual therapy improves perianal Crohn's disease as measured by a new disease activity index. McMaster IBD Study Group. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:27-32. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn's-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1:514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1940] [Cited by in RCA: 2181] [Article Influence: 48.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Pommaret E, Benfredj P, Soudan D, de Parades V. Sphincter-sparing techniques for fistulas-in-ano. J Visc Surg. 2015;152:S31-S36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cestaro G, De Rosa M, Gentile M. Treatment of fistula in ano with fibrin glue: preliminary results from a prospective study. Minerva Chir. 2014;69:225-228. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Yeung JM, Simpson JA, Tang SW, Armitage NC, Maxwell-Armstrong C. Fibrin glue for the treatment of fistulae in ano--a method worth sticking to? Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:363-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sehgal R, Koltun WA. Fibrin glue for the treatment of perineal fistulous Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2216-2219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Garg P. Is fistulotomy still the gold standard in present era and is it highly underutilized? Int J Surg. 2018;56:26-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hyman N, O'Brien S, Osler T. Outcomes after fistulotomy: results of a prospective, multicenter regional study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:2022-2027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Baumgart DC, Dignass A, Nachury M, Ferrante M, Kazemi-Shirazi L, Grimaud JC, de la Portilla F, Goldin E, Richard MP, Leselbaum A, Danese S; ADMIRE CD Study Group Collaborators. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1281-1290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 628] [Cited by in RCA: 727] [Article Influence: 80.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Baumgart DC, Dignass A, Nachury M, Ferrante M, Kazemi-Shirazi L, Grimaud JC, de la Portilla F, Goldin E, Richard MP, Diez MC, Tagarro I, Leselbaum A, Danese S; ADMIRE CD Study Group Collaborators. Long-term Efficacy and Safety of Stem Cell Therapy (Cx601) for Complex Perianal Fistulas in Patients With Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: 1334-1342. e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Garcia-Olmo D, Herreros D, Pascual I, Pascual JA, Del-Valle E, Zorrilla J, De-La-Quintana P, Garcia-Arranz M, Pascual M. Expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistula: a phase II clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:79-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cheng F, Huang Z, Li Z. Mesenchymal stem-cell therapy for perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:613-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Bor R, Fábián A, Farkas K, Molnár T, Szepes Z. Human mesenchymal stem cell therapy in the management of luminal and perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease - review of pathomechanism and existing clinical data. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:737-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |