Published online Oct 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i10.1279

Peer-review started: April 20, 2021

First decision: June 24, 2021

Revised: June 24, 2021

Accepted: August 30, 2021

Article in press: August 30, 2021

Published online: October 27, 2021

Processing time: 188 Days and 12.9 Hours

There are several case reports of acute cholecystitis as the initial presentation of lymphoma of the gallbladder; all reports describe non-Hodgkin lymphoma or its subtypes on histopathology of the gallbladder tissue itself. Interestingly, there is no description in the literature of Hodgkin lymphoma causing hilar lymphadenopathy, inevitably presenting as ruptured cholecystitis with imaging mimicking gallbladder adenocarcinoma.

A 48-year-old man with a past medical history of diabetes mellitus presented with progressive abdominal pain, jaundice, night sweats, weakness, and unintended weight loss for one month. Work-up revealed a mass in the region of the porta hepatis causing obstructions of the cystic and common hepatic ducts, gallbladder rupture, as well as retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. The clinical picture and imaging findings were suspicious for locally advanced gallbladder adenocarcinoma causing ruptured cholecystitis and cholangitis, with metastases to retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Minimally invasive techniques, including endoscopic duct brushings and percutaneous lymph node biopsy, were inade

This clinical scenario highlights the importance of histopathological assessment in diagnosing gallbladder malignancy in a patient with gallbladder perforation and a grossly positive positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan. For both gallbladder adenocarcinoma and Hodgkin lymphoma, medical and surgical therapies must be tailored to the specific disease entity in order to achieve optimal long-term survival rates.

Core Tip: Here we present a case of Hodgkin lymphoma masquerading as gallbladder adenocarcinoma. In our patient, Hodgkin lymphadenopathy in the region of the porta hepatitis led to obstructions of the cystic and common hepatic ducts, causing acute cholecystitis and subsequent gallbladder perforation with associated cholangitis. Our case highlights the importance of histopathological assessment in diagnosing gallbladder malignancy when a patient presents with gallbladder perforation and a grossly positive positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan. For either gallbladder adenocarcinoma or Hodgkin lymphoma, chemotherapy tailored to the disease (and appropriate surgical intervention) are essential to achieve the best chance of cure and long-term survival.

- Citation: Manesh M, Henry R, Gallagher S, Greas M, Sheikh MR, Zielsdorf S. Hodgkin lymphoma masquerading as perforated gallbladder adenocarcinoma: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(10): 1279-1284

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i10/1279.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i10.1279

Primary lymphoma of the gallbladder is rare but likely fits on the spectrum of lymphomas occurring in the gastrointestinal tract[1]. There are several case reports of acute cholecystitis as the initial presentation of lymphoma of the gallbladder, all of which describe non-Hodgkin lymphoma or its subtypes on histopathology of the gallbladder specimen[2-7]. Interestingly, there is no description in the literature of Hodgkin lymphoma causing hilar lymphadenopathy, inevitably presenting as ruptured cholecystitis and mimicking metastatic gallbladder adenocarcinoma on imaging. Here we present a case of Hodgkin lymphadenopathy in the region of the porta hepatitis which led to obstructions of the cystic and common hepatic ducts, causing an acute cholecystitis, gallbladder perforation, and cholangitis.

A 48-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department with acute nausea and vomiting for one day but did also endorse vague symptoms of nausea for the preceding two weeks. He also described having subjective fevers at home with rare right upper quadrant pain and without evidence of jaundice.

Patient described progressive right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, night sweats, weakness, and unintended weight loss for one month. His symptoms had worsened on the week prior to arrival, at which time he began to experience decreased oral intake with nausea. His acute onset of non-bloody, nonbilious vomiting on day prior to arrival is what led him to seek care. He initially presented to an urgent care center where computed tomography (CT) scan was done and showed acute cholecystitis. He was then sent to the emergency room.

The patient had a past medical history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension. His only home medication was a prostate medication of unknown name. He also had a remote history of laparoscopic appendectomy.

Family history was noncontributory. Patient denied any alcohol, tobacco or illicit drug use.

His vital signs on arrival were temperature 36.4 ℃, heart rate 110 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, blood pressure of 125/82 mmHg. Physical exam was notable for right upper quadrant tenderness without peritoneal signs. His skin was jaundiced.

Laboratory findings were significant for leukocytosis (white blood cell count 18.3 K/mm3) and hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin 14.5 mg/dL). The remainder of the complete blood count and blood chemistries, as well as liver function panel were normal. Tumor markers included CEA level of 1.2 µg/L and CA19-9 level of 21 U/L. Electrocardiogram and chest X-ray were also normal.

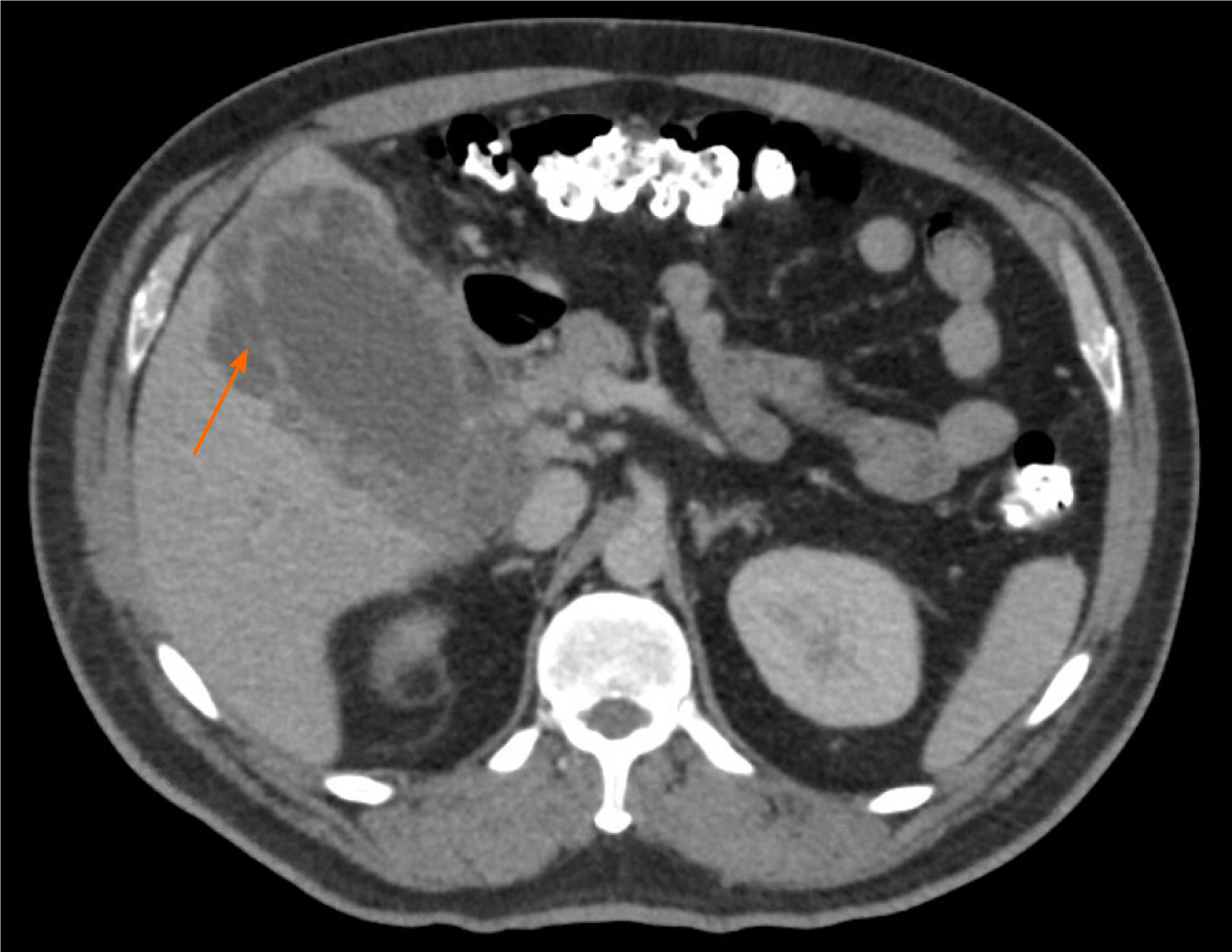

An abdominal ultrasound demonstrated a distended gallbladder with a thickened, edematous wall, gallstones, and an apparent defect in the wall, as well as intrahepatic and extrahepatic ductal dilation. A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography identified a T2 hypointense right hepatic lobe lesion that involved the right hepatic artery and narrowing of the common bile duct (CBD). CT again demonstrated a contained perforation of the gallbladder, moderate intrahepatic ductal dilation, possible mass within the porta hepatis, and long narrowing of the CBD (Figure 1). Additional findings consisted of multiple large retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes measuring up to 2.6 cm, located in proximity to the aortic bifurcation. Given the possibility of malignancy, a chest CT was performed to evaluate for metastatic disease, which demonstrated abnormally enlarged right hilar lymph nodes.

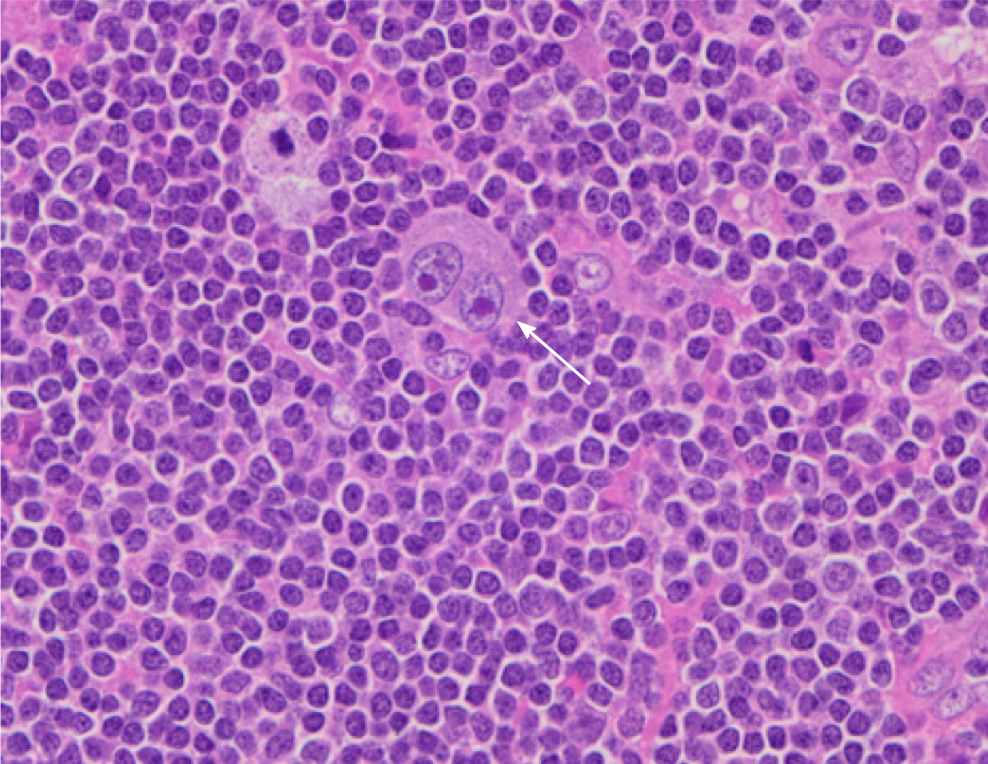

Pathologic examination of the para-aortic lymph nodes provided a definitive diagnosis of mixed-cellularity classic Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 2). The gallbladder demonstrated chronic cholecystitis without evidence of dysplasia, adenocarcinoma, or lymphoma.

The patient received intravenous antibiotics for presumed cholangitis and underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for sphincterotomy and stent placement in the common hepatic duct. Bile duct brushings were negative for malignant cells. The patient then underwent percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement. A specimen of the bilious drainage was cytologically negative for malignancy, but fluid culture grew extended spectrum beta-lactamase Escherichia coli. The patient was transitioned to the appropriate oral antibiotics and was discharged with the cholecystostomy tube in place.

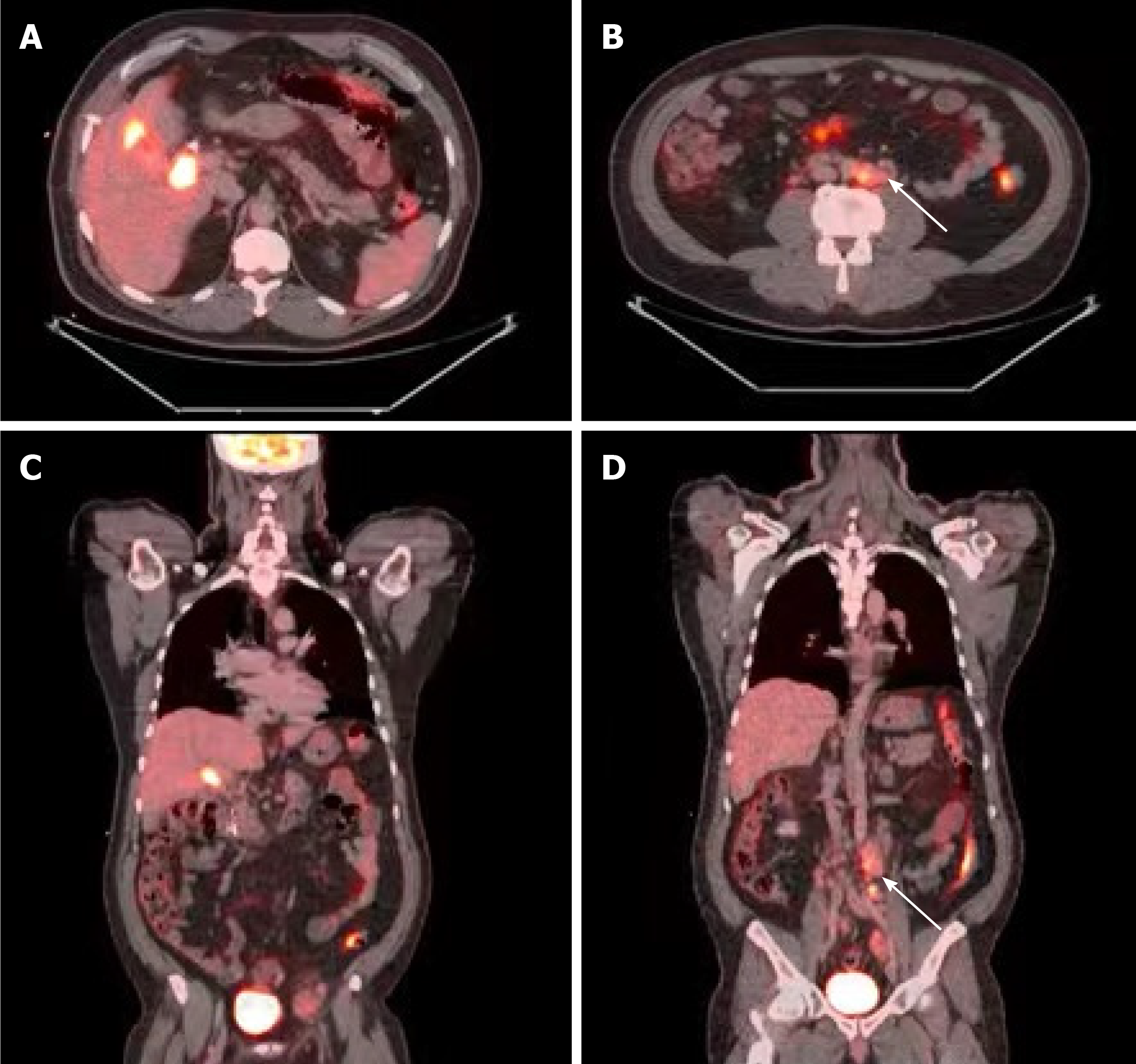

The differential diagnosis included locally advanced (and metastatic) gallbladder adenocarcinoma, hilar cholangiocarcinoma, lymphoma, or severe cholecystitis and cholangitis causing intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy. One month after his initial presentation, the patient underwent positron emission tomography with 2-deoxy-2-(fluorine-18) fluoro-D-glucose integrated with CT (18F-FDG PET-CT) and ultrasound-guided biopsy of the largest iliac lymph node. The 18F-FDG PET-CT demonstrated a soft tissue density associated with intense hypermetabolic activity in the region of the gallbladder fossa at the junction of the cystic duct and proximal CBD. It also demonstrated hypermetabolic activity in the gallbladder wall and in several lymph nodes in the para-aortic region extending to the iliac vessels (Figure 3). The lymph node biopsy showed the presence of lymphoid tissue but was otherwise inadequate for diagnosis.

The patient subsequently underwent surgical intervention for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. A para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed first in order to obtain a diagnosis. If this was positive for gallbladder adenocarcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma, any further operative intervention would be aborted in favor of chemotherapy for metastatic disease. However, intra-operative pathology showed no evidence of adenocarcinoma, but rather cellular atypia suggesting lymphoma. An open cholecystectomy, without liver resection or portal lymphadenectomy was then performed.

The patient recovered well post-operatively and was discharged on post-operative day eight. Upon follow up to the surgery clinic, he was pleased with his care and thankful that a diagnosis had been made. He is scheduled to receive adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine chemotherapy as treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma.

Primary lymphoma of the gallbladder is rare but likely fits on the spectrum of lymphomas occurring in the gastrointestinal tract[5,7]. There are several case reports of acute cholecystitis as the initial presentation of lymphoma of the gallbladder and all describe non-Hodgkin's lymphoma or its subtypes on histopathology[2-5]. On the contrary, our case report describes Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the portal lymph nodes, and benign pathology of the gallbladder itself, presenting as ruptured cholecystitis and mimicking gallbladder adenocarcinoma on imaging. Other authors have written about clinical situations where there is a mass in the region of the gallbladder or biliary ducts causing acute acalculous cholecystitis. In these settings, the distinction between lymphoma and gallbladder adenocarcinoma relies on histopathological assessment[2].

Given our patient’s initial presentation with an inflamed, thickened and perforated gallbladder, along with 18F-FDG PET avidity in a mass-like structure within the region of the gallbladder fossa and CBD, our differential diagnosis was highly concerning for primary gallbladder malignancy. Still, confirmation by tissue diagnosis was essential. Regarding surgical planning: With the mass-like structure involving the gallbladder, CBD, and right hepatic artery—surgical intervention would necessitate a right hepatic lobectomy. However, with distant lymphadenopathy concerning for metastatic disease, aggressive hepatobiliary resection(s) such as right hepatic lobectomy would be contraindicated. Conversely, if the mass-like structure was not a primary gallbladder or bile duct malignancy, the ruptured cholecystitis required surgical intervention, albeit less aggressive than liver resection. Unfortunately, minimally invasive techniques, including endoscopic duct brushings and percutaneous lymph node biopsy, were inadequate for pre-operative tissue diagnosis. Hence, exploratory laparotomy and para-aortic lymphadenectomy were required for histopathological assessment and definitive diagnosis. Once intra-operative pathology returned as likely Hodgkin lymphoma, open cholecystectomy was performed.

Classic Hodgkin lymphoma typically presents as an asymptomatic supradiaphragmatic lymphadenopathy. Constitutional “B” symptoms such as high fevers, night sweats and unintended weight loss occur in 33% of cases. In retrospect, our patient had constitutional “B” symptoms for at least one month leading up to his presentation to the hospital. Interestingly, peripheral and abdominal lymphadenopathy are prominent in the mixed-cellularity type, which was the subtype diagnosed in this case report. The pathologic hallmark of classical Hodgkin lymphoma is large multinucleated Reed-Sternberg cells with a characteristic reactive cellular background[8]. Hodgkin lymphoma is unique in that malignant cells (Reed-Sternberg cells) only constitute a small portion of the cell population within each tumor (Figure 2). As such, fine-needle aspiration and core-needle biopsies are often inadequate to make a definitive diagnosis[9]. In our case as well, several biopsies were non-diagnostic prior to our operative intervention and excisional lymph node biopsy.

To our knowledge, there are no cases documented of Hodgkin lymphoma presenting with gallbladder and biliary obstruction, leading to gallbladder perforation and cholangitis, respectively. Moreover, this unique case revealed benign pathology of the gallbladder. This further supports a pathophysiology that is distinct from the current literature review of acute cholecystitis due to primary lymphoma of the gallbladder.

This case highlights the importance of histopathological assessment in diagnosing gallbladder malignancy in a patient with gallbladder perforation and a grossly positive PET-CT scan. For either gallbladder adenocarcinoma or Hodgkin lymphoma, chemotherapy tailored to the disease (and appropriate surgical intervention) are essential to achieve the best chance of cure and long-term survival[4]. Therefore, in patients like ours, lymphoma must be ruled out definitively by pathology, which in this case required exploratory laparotomy and excisional lymph node biopsy.

We thank Drs Maria Stapfer and Hector Ramos for their comments in consultation.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Renzo ND S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Pezzuto R, Di Mauro D, Bonomo L, Patel A, Ricciardi E, Attanasio A, Manzelli A. An Unusual Case of Primary Extranodal Lymphoma of the Gallbladder. Hematol Rep. 2017;9:6972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Doherty B, Palmer W, Cvinar J, Sadek N. A Rare Case of Systemic Adult Burkitt Lymphoma Presenting as Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6:e00048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Katiyar R, Patne SC, Agrawal A. Primary B-cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma of Gallbladder Presenting as Cholecystitis. J Lab Physicians. 2015;7:67-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lakananurak N, Laichuthai N, Treeprasertsuk S. Acalculous Cholecystitis as the Initial Presentation of Systemic Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. ACG Case Rep J. 2015;2:110-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shah KS, Shelat VG, Jogai S, Trompetas V. Primary gallbladder lymphoma presenting with perforated cholecystitis and hyperamylasaemia. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98:e13-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tishler M, Rahmani R, Shilo R, Armon S, Abramov AL. Large-cell lymphoma presenting as acute cholecystitis. Acta Haematol. 1987;77:51-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yadav S, Chisti MM, Rosenbaum L, Barnes MA. Intravascular large B cell lymphoma presenting as cholecystitis: diagnostic challenges persist. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1259-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ansell SM. Hodgkin Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1574-1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Townsend W, Linch D. Hodgkin's lymphoma in adults. Lancet. 2012;380:836-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |