Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.98995

Revised: December 9, 2024

Accepted: January 23, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 231 Days and 23.7 Hours

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a prevalent metabolic disorder. Despite the availability of numerous pharmacotherapies, a range of adverse reactions, in

Core Tip: The applicability and long-term use of drugs for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) treatment is limited due to their adverse effects. Drugs that activate AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) via calcium signaling exhibit fewer adverse effects such as lactic acidosis. However, the potency of these drugs is limited. Therefore, it is necessary to screen novel drugs with high efficacy but few adverse effects. The calcium channels control intracellular calcium flux, which could be potential targets for T2DM treatment via AMPK. This review summarizes 15 calcium channels, and discuss the potential of targeting these calcium channels for T2DM treatment.

- Citation: Zhu JX, Pan ZN, Li D. Intracellular calcium channels: Potential targets for type 2 diabetes mellitus? World J Diabetes 2025; 16(4): 98995

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i4/98995.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.98995

Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic conditions characterized by hyperglycemia. It is the most common metabolic condition in the world, and its incidence is increasing. There are several types of diabetes. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common type[1], and it is characterized by insulin resistance[2]. Individuals with T2DM exhibit symptoms including polydipsia, polyphagia, polyuria, weight loss, xerostomia, and fatigue. In severe cases, it leads to diabetic foot, diabetic retinopathy, heart failure, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and even amputation and death[3-6]. Under normal conditions, insulin regulates the cellular trafficking of glucose transporter isoform 4 (GLUT4) protein to the plasma membrane (PM), facilitating the transport of glucose from the blood into cells, thereby maintaining glucose homeostasis[7]. In the case of chronic excessive nutrition, the pancreas will constantly secrete elevated amounts of insulin, causing dysfunction of islet β cells and ultimately insulin resistance[8], alongside GLUT4 retention in storage vesicles, leading to high blood glucose levels[9].

The pharmacological treatment of T2DM mainly encompasses oral medication and insulin injection. Due to the limited acceptance of insulin injection, oral medication remains the primary treatment for the majority of patients[10]. Oral medications for T2DM treatment that are commercially available can be categorized into insulin secretagogues and non-insulin antidiabetic agents (Table 1). Targets for insulin secretagogues primarily encompass the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), and the ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels)[11]. Both GLP-1 receptor agonists (exenatide) or DPP-4 inhibitors (sitagliptin) can enhance the activity of GLP-1, which promotes glucose-dependent insulin secretion, facilitating glucose uptake. Inhibitors of the KATP channel (glibenclamide) modulate K+/Ca2+ homeostasis, leading to an enhanced influx of calcium, which subsequently facilitates insulin secretion. Long-term utilization of insulin secretagogues, including sitagliptin and glibenclamide, has been associated with various adverse reactions such as hypoglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, obesity, gastrointestinal discomfort, renal impairment, and allergic responses[12,13].

| Classification | Medication | Target | Adverse reaction | Limitation |

| Insulin secretagogue | Glibenclamide | ATP-sensitive potassium channel | Hypoglycemia; weight gain; gastrointestinal disorders | Contraindicated in patients with sulfonamide allergies |

| Tirzepatide | Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor | Risk of thyroid myeloid tumors | Contraindicated in patients with medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplastic syndrome type 2 | |

| Semaglutide | Risk of thyroid myeloid tumors | |||

| Exenatide | Risk of pancreatitis | |||

| Sitagliptin | Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 | Risk of pancreatitis; metabolic and nutritional disorders | Contraindicated in patients with severe liver and kidney dysfunction | |

| Non-insulin antidiabetic agent | Rosiglitazone | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ | Heart failure; risk of fractures | Contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation |

| Acarbose | α-Glucosidase | Abdominal discomfort; flatulence | Contraindicated in patients with chronic gastrointestinal dysfunction | |

| Metformin | AMP-activated protein kinase | Risk of lactic acidosis; vitamin B12 deficiency | Contraindicated in patients with metabolic acidosis | |

| Canagliflozin | Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 | Polyuria and urinary tract infection; risk of diabetes ketoacidosis and amputations | Used with caution during urinary system infections |

The targets of non-insulin antidiabetic agents mainly include AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2), and α-Glucosidase[14]. AMPK agonists (such as metformin) can inhibit liver gluconeogenesis and promote GLUT4 translocation to the PM. SGLT2, a transport protein located in the proximal tubules of the kidneys, dominates the reabsorption of glucose. SGLT2 inhibitors (such as canagliflozin) reduce renal glucose reabsorption, causing increased urinary excretion of glucose and subsequently lowering blood glucose levels. α-Glucosidase, which is located in the mucosa of the small intestine, functions as a hydrolytic enzyme responsible for breaking down dietary carbohydrates into glucose. α-Glucosidase inhibitors (such as acarbose) can delay the absorption of glucose, effectively reducing postprandial blood glucose levels. Although non-insulin antidiabetic agents exhibit potent hypoglycemic effects, they are accompanied by several adverse reactions, including anemia, dizziness, allergic responses, gastrointestinal complications, reproductive system infections, and liver dysfunction (Table 1)[15].

Oral medications exhibit excellent hypoglycemic effects. However, these drugs are accompanied by various adverse reactions that restrict their applicability to a specific population and duration of time. Therefore, it is necessary to explore novel targets for T2DM treatment with a reduced incidence of adverse reactions. In this review, we propose that calcium-permeable ion channels could be powerful therapeutic targets for T2DM treatment via activating AMPK. The details of these calcium ion channels located on cellular organelles or PM are discussed in what follows.

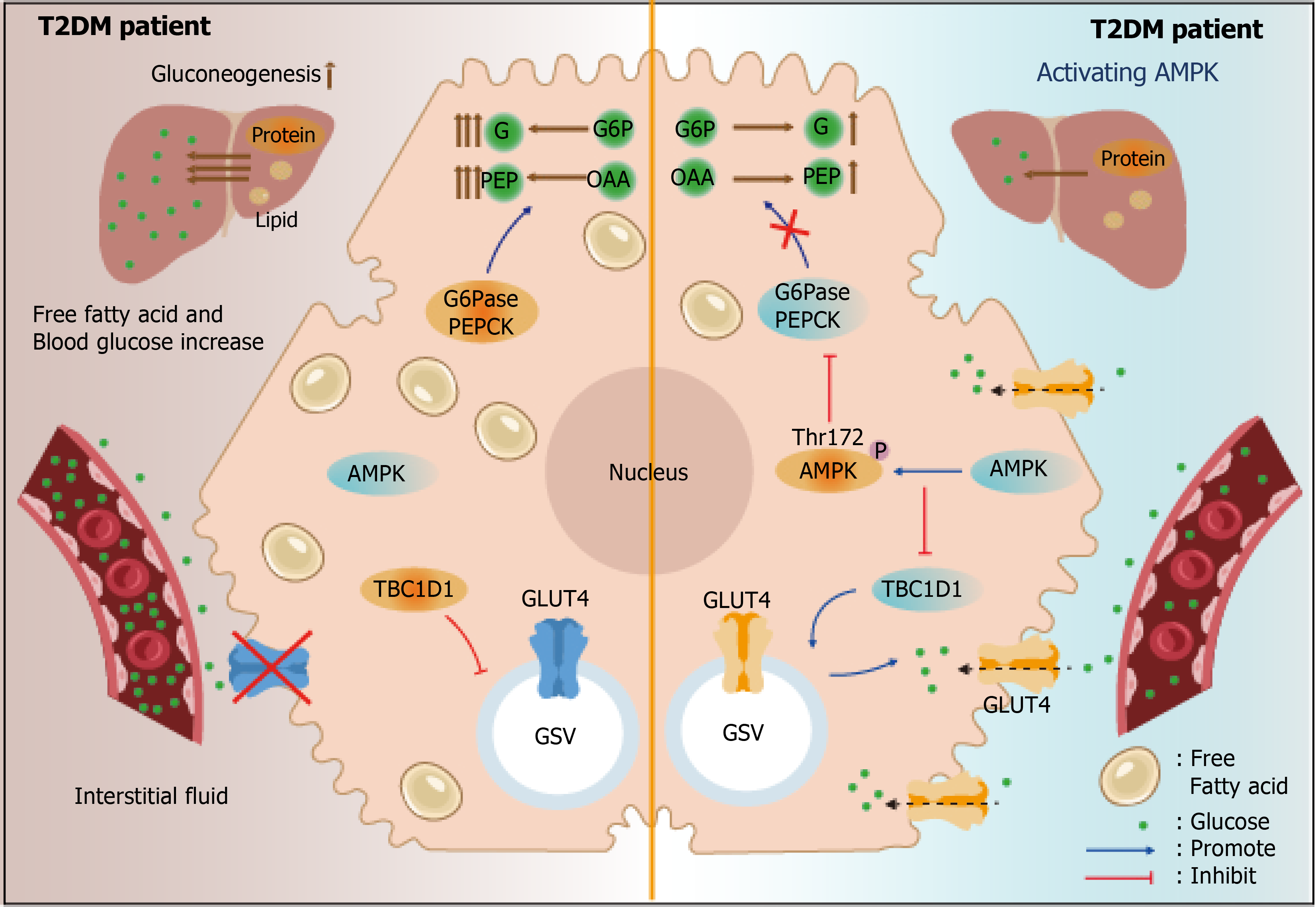

As summarized in Table 1, currently, there are many targets for T2DM treatment. Among them, AMPK is one of the most powerful targets. AMPK, a heterotrimeric complex, comprises α, β, and γ subunits. The α subunit assumes a catalytic role, encompassing serine/threonine kinase domains with a small N-lobe and a larger C-lobe[16]. AMPK can inhibit TBC1 domain family member 1, which restricts GLUT4 in the cytoplasm, thus facilitating GLUT4 to translocate to the PM[17]. AMPK has also been reported to reduce liver gluconeogenesis, which is significantly elevated in T2DM patients, thus facilitating a decrease in glucose levels (Figure 1)[18].

The phosphorylation of the α subunit at Thr172 indicates the activation of AMPK, which is mainly achieved through energy-sensing or calcium signaling[19]. Drugs that activate AMPK via the energy-sensing mechanism include canagliflozin, thiazolidinedione, glibenclamide, and metformin[20-22]. These drugs show powerful potency; however, they are also associated with various adverse effects. For example, metformin, a potent medication for T2DM treatment, inhibits the activity of mitochondrial respiratory complex I, resulting in changes in the AMP/ATP ratio and subsequently activation of AMPK through upstream kinase liver kinase B1. Metformin exhibits a low risk of hypoglycemia, mitigates anorexia, and is compatible with the majority of clinical medications[23]. Unfortunately, patients administered metformin experience significant weight loss and exhibit a deficiency in vitamin B12, and most significantly, long-term application of metformin causes excessive anaerobic respiration and lactic acidosis[24-26]. Symptoms of lactic acidosis include weakness, diarrhea, and emesis, eventually causing organ damage, respiratory insufficiency, and even death[27,28]. Although lactic acidosis is a rare condition, its mortality rate is alarmingly reaching 50%. Therefore, it is crucial to explore potential targets via AMPK activation that retain high potency without causing lactic acidosis. Notably, drugs that acti

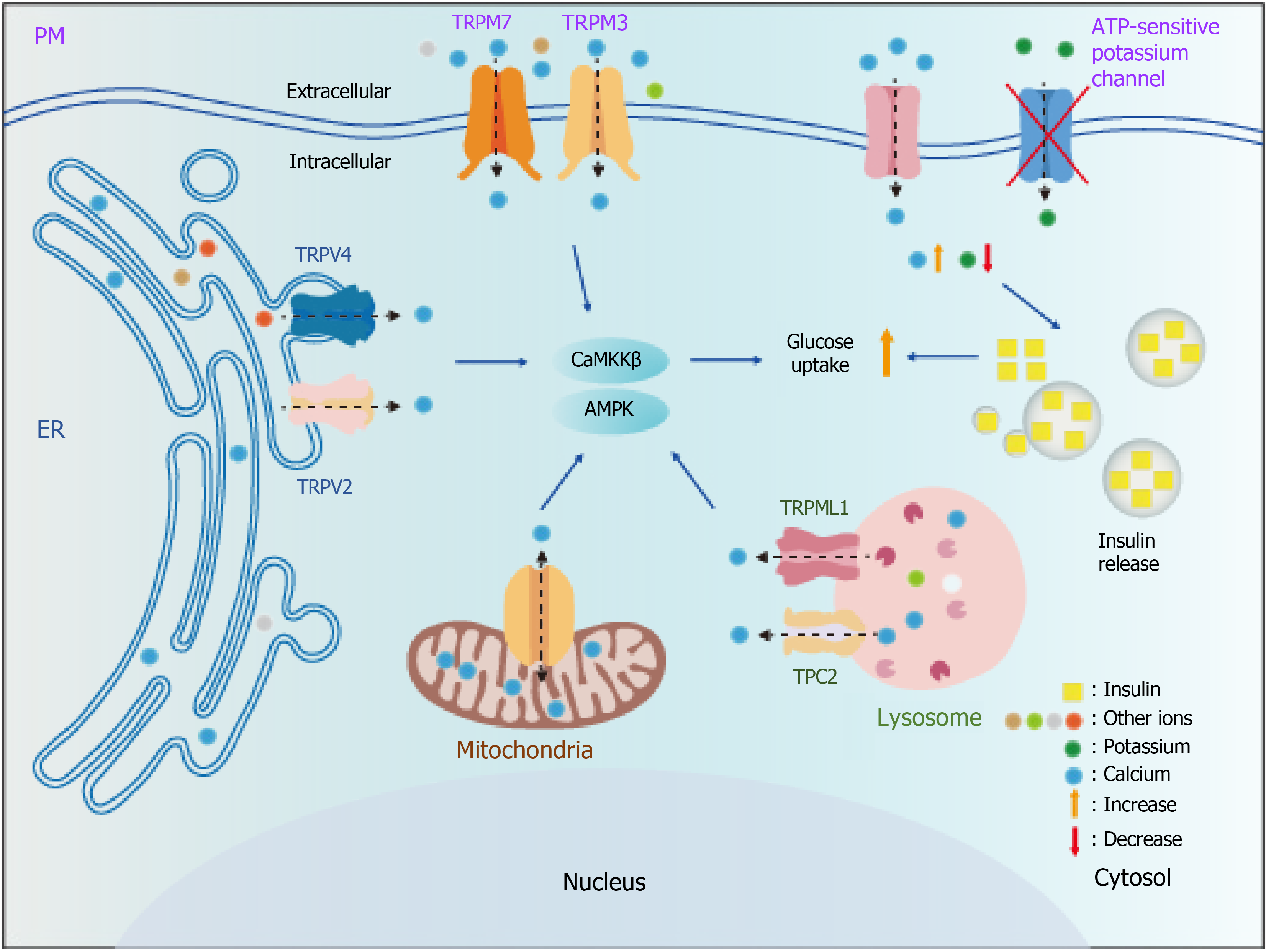

Cellular calcium stores include mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and lysosomes, which control the storage, uptake, and release of calcium. Calcium signaling is mainly released from calcium ion channels located on organelles. These agonists or inhibitors targeting ion channels generally exhibit high specificity. Thus, we propose that calcium ion channels located on organelle membranes could be potential targets for T2DM treatment, and specific agonists or inhibitors of these ion channels could be potential therapeutic drugs for T2DM. In the following section, we summarize the calcium channels that have the potential to be T2DM targets.

By virtue of their pivotal roles in maintaining ion homeostasis, ion channels orchestrate organelle functions[34]. However, the current understanding of ion channels and their association with metabolic diseases remains limited. In what follows, we introduce the calcium ion channels located on organelles and the PM and discuss the possibility of these channels participating in AMPK activation (Table 2).

| Channel | Subcellular location | Agonists | Inhibitors | Permeability | Structural features | Regulating AMPK | Role in T2DM |

| VDAC1 | Mitochondria | - | DIDS | Ca2+ | The β-barrel architecture is composed of 19 β-strands with an α-helix located horizontally midway within the pore | Change in the AMP: ATP ratio activates AMPK | Mediates ER stress, a characteristic of T2DM |

| MCU | Spermine | Ruthenium red | Ca2+ | Consists of six MCU subunits, an essential MCU regulator, and a solute carrier | Reduces lipid accumulation | ||

| NCLX | - | CGP37157 | Ca2+/Na+ | Three (or four) Na+ exchanged for one Ca2+ | - | - | |

| mCHE | - | - | Ca2+/H+ | Two H+ exchanged for one Ca2+ | - | - | |

| SERCA2/3 | ER | Compound A | Thapsigargin | Ca2+ | Tetramer with both N2 and C2, resembling a spherical structure. | Calcium accumulation induces AMPK activation | Alleviates heart failure |

| TRPV1 | ER/PM | Capsaicin | A-1165442 | Ca2+/Na+ | Each monomer in the tetramer exhibits the classic six transmembrane helix architecture of voltage-gated ion channels in its transmembrane domain | Improves glucose uptake | |

| RyRs | ER | Compound 7f | Dantrolene | Ca2+/K+/Na+ | Contains four subunits, each with six transmembrane segments but lacking voltage sensors | - | Enhances insulin secretion |

| IP3Rs | ER | - | Xestospongin C | Ca2+/K+/Na+ | Tetramer comprising 2671 residues per subunit with a large amino-terminal cytoplasmic domain followed by a transmembrane domain | - | |

| TRPML1 | Lysosome | MK6-83/ML-SA1 | ML-SI1/ML-SI3 | Ca2+/Fe2+/Zn2+/Na+ | A tetramer consisting of four identical 6-transmembrane subunits | Calcium accumulation induces AMPK activation | Enhances insulin pathway |

| TPC1/2 | Riluzole | Trans-Ned 19 | Ca2+/Na+ | Each subunit has two similar 6-transmembrane helical repeats and two subunits are arranged in pseudo-tandem | - | - | |

| TRPM2 | PM | NAD, NAADP | Flufenamic acid | Ca2+/Na+ | Four shared homologous regions: A transmembrane domain consisting of six transmembrane helices, a TRP helix, and C-terminal domains containing the conserved TRP domain followed by a coiled-coil region that varies among members | - | Improves glucose uptake |

| TRPM3 | Nifedipine | Promethazine | Ca2+/Mg2+/Zn2+ | Calcium accumulation induces AMPK activation | - | ||

| TRPM4 | CIM0216 | - | Ca2+/Na+ | - | Improves glucose uptake | ||

| TRPM5 | - | - | Zn2+/Mg2+/Mn2+ | - | |||

| TRPM7 | Clozapine/naltriben | Ruthenium red | Ca2+/Zn2+/Mg2+/Mn2+ | Calcium accumulation induces AMPK activation | Enhances insulin secretion |

Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel: Voltage-dependent anion-selective channels (VDACs) are widely expressed on the outer mitochondrial membrane and consist of three subtypes: VDAC1-3. The primary structure of the VDAC is the β fold. Modulating the conformation of the β-barrel, which consists of a combination of β-spirals and β-folds, enables precise control over the VDAC gating mechanism. Calcium requires the involvement of VDAC to pass through the outer mitochondrial membrane[35]. The open state of the VDAC maintains a low calcium flux to support mitochondrial respiration, while in its closed state, VDAC enhances calcium permeation, thereby facilitating its opening under conditions of low conductivity[36].

Currently, the majority of studies have focused on VDAC1, while the physiological roles of VDAC2 and VDAC3 remain unclear. VDAC1 is responsible for mitochondrial protein release and mitochondria-mediated cellular apoptosis. Studies have shown that VDAC1 inhibitors disrupt mitochondrial metabolism, leading to an increase in the AMP: ATP ratio and AMPK activation[37]. Moreover, the expression of VDAC1 is upregulated in T2DM patients. The employment of VDAC1 inhibitors enhances insulin secretion and ameliorates hyperglycemia (Table 2)[38].

Mitochondrial calcium uniporter: The mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) is located on the inner mitochondrial membrane, which regulates the uptake of calcium by mitochondria. The MCU complex consists of four components: the pore-forming subunit, the essential MCU regulator, mitochondrial calcium uptake protein 1, and mitochondrial calcium uptake protein 2. To reach the mitochondrial matrix, calcium requires the involvement of the MCU complex[39]. MCU detects increased levels of calcium through the EF-hand domains of the mitochondrial calcium uptake protein, facilitating calcium uptake after its conformational alterations[40].

MCU-mediated calcium uptake is required for the maintenance of hepatic ATP content. The absence of MCU results in a reduction in ATP levels, potentially inducing activation of AMPK. Interestingly, contrary to expectations, studies have shown that the absence of MCU leads to a significant reduction in AMPK activation levels[41]. Although the precise relationship between AMPK and MCU remains to be elucidated, MCU is significantly decreased in T2DM patients[42]. MCU restoration effectively reduces liver lipid accumulation and alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy, a complication of T2DM, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target for T2DM (Table 2)[43].

Mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and mitochondrial Ca2+/H+ exchanger: Mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCLX) and mitochondrial Ca2+/H+ exchanger (mCHE) have been identified as mitochondrial calcium efflux systems for ion exchange. Both NCLX and mCHE are capable of facilitating the release of calcium from mitochondria[44]. NCLX or mCHE functions as a transporter through the formation of hexameric structures, facilitating ion exchange and calcium release. NCLX facilitates Na+/Ca2+ exchange by mediating the interaction between multiple residues and ions[45]. Although research has demonstrated the neuroprotective effects of NCLX, it remains unclear whether calcium release from NCLX is implicated in AMPK activation or T2DM treatment[46]. In hepatocytes, the activity of NCLX is relatively low, while the involvement of mCHE is essential for calcium ion exchange and ATP generation[47]. However, the precise structure and physiological functions of mCHE remain unknown.

Briefly, mitochondrial ion channels such as MCU and VDAC are known to be associated with AMPK and T2DM treatment. However, the roles of ion channels, such as NCLX and mCHE in T2DM treatment have not been investigated although they have the potential to activate AMPK.

Sarcoplasmic/ER calcium ATPase: Sarcoplasmic/ER calcium ATPase (SERCA) is responsible for uptake of calcium into the ER lumen, thereby maintaining intracellular calcium homeostasis. SERCA isoforms are encoded by three genes, SERCA 1, 2, and 3. These subtypes demonstrate specificity in terms of tissue and development. SERCA1 is primarily expressed in skeletal muscle, while SERCA2 exhibits predominant expression in cardiac muscle and is co-expressed with SERCA3 in various tissues. They are P-type ion-activated ATPases, which are activated when the intracellular calcium concentration exceeds 10-4 mmol/L[48]. Calcium binds to the E2 domain of SERCA, inducing its phosphorylation and causing conformational changes, thereby entering the ER[49].

SERCA2a, a subtype of SERCA expressed in the heart, is closely related to heart failure, which is a complication of T2DM[50]. The expression of SERCA2a is downregulated in heart tissue. Restoration of SERCA2a expression holds potential for the treatment of heart failure[51]. Reductions in the expression of SERCA2b and SERCA3 have been observed in the islet β cells of T2DM patients, resulting in impaired insulin secretion[52,53]. Therefore, restoring SERCA2/3 levels may enhance insulin secretion, suggesting a potential therapeutic strategy. Treatment with saikosaponin-d, an inhibitor of SERCAs, causes intracellular calcium accumulation and CaMKKβ/AMPK activation (Table 2)[54]. However, the potential of SERCA-induced AMPK activation remains to be elucidated in T2DM treatment.

Ryanodine receptors and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptors: Ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and inositol 1,4,5-tripho

RyRs release a large amount of calcium from the ER into the cytoplasm during muscle contractions. The antagonist dantrolene directly acts as a skeletal muscle relaxant by exploiting this mechanism. RyRs are commonly associated with hyperthermia and central core disease, while IP3Rs are more associated with cancer[57]. Interestingly, MCU takes up the calcium released from these channels for ATP production, further enhancing insulin secretion and treating T2DM (Table 2)[58]. However, there is currently no evidence to suggest a direct correlation between calcium release mediated by these two channels and the activation of AMPK or T2DM treatment.

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1: Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) exhibits sensitivity to various stimuli[59]. The vast majority of functional TRPV1 is located on the ER[60]. TRPV1 is a tetramer formed by subunits with six transmembrane segments (S1-S6). The binding sites of selective filters exhibit an affinity for calcium[61]. Temperature modulation is observed in TRPV1[62]. TRPV1 is involved in nociception, thermoregulation, and the modulation of cough[63]. Research has shown that AMPK activation and T2DM treatment can be facilitated by TRPV1-released calcium from the ER (Table 2)[64].

Inhibiting TRPV1 reduces the intracellular calcium concentration and the phosphorylation of CaMKKβ and AMPK. The absence of TRPV1 causes several T2DM complications[65-67]. In contrast, capsaicin, piperine, and total sesquiterpene glycosides induce TRPV1-mediated CaMKKβ and AMPK activation to promote GLUT4 translocation to the PM and improve glucose homeostasis (Table 2)[68-71]. Interestingly, some researchers also believe that TRPV1 mediates the secretion of GLP-1 to regulate glucose homeostasis[72].

Transient receptor potential mucolipins: There are two subtypes of transient receptor potential mucolipins (TRPMLs) in humans: TRPML1 and TRPML2. TPRML1 is a calcium-permeable ion channel localized within lysosomes. Encoded by the MCOLN1 gene, it exhibits widespread expression in various tissues, including hepatic tissue. TRPML2 is predominantly observed in lymphoid and bone marrow tissues. The structure of TRPMLs is similar to that of other TRP channels, including six transmembrane helices (S1-S6), two pore helices (PH1 and PH2), and a luminal domain. The TRPML agonist ML-SA1 binds to hydrophobic cavities formed by the adjacent PH1, S5, and S6[73]. The tetramer formed by the first and second transmembrane domains of TRPMLs actively participates in ion transport[74].

TRPMLs regulate lysosomal ion homeostasis, membrane trafficking, and signal transduction. The absence of TRPML1 causes lysosomal storage diseases such as type IV mucolipidosis[75]. TRPML2 is associated with inflammation and immunity[76]. Notably, recent research demonstrated that TRPML1 modulates autophagy in a TFEB-independent manner involving CaMKKβ/AMPK activation[77]. The activation of the insulin pathway by artemisia leaf extract is dependent on TRPML1 (Table 2)[78].

Two-pore channels: The two-pore channels (TPCs) are calcium-permeable channels localized on the membranes of lysosomes. TPCs are involved in various physiological processes, such as cellular growth and metabolism. The TPC family consists of two human members, namely TPC1 and TPC2. TPC1/2 function as homodimers, with each subunit comprising 12 transmembrane segments[79]. The EF domain of TPC1/2 connects these transmembrane fragments and contains two calcium-binding sites[80]. TPC1/2 are involved in the regulation of multiple internal lysosomal transport pathways, and thus the absence of TPC1/2 may result in the development of lysosomal storage diseases[81]. Recent research has demonstrated that TPC1/2 serve as a target for treating pro-inflammatory diseases such as allergic hypersensitivity. Notably, TPC1/2 are required in glutamate-mediated AMPK activation. The TPC1/2 inhibitor Ned-19 effectively inhibited this process (Table 2)[82]. However, the investigation of the relationship between lysosomal ion channels and AMPK-mediated T2DM treatment remains limited.

Transient receptor potential melastatin: There are various calcium ion channels on the PM, which are responsible for intracellular and extracellular ion exchange. This article only focuses on transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM), which has been reported to be involved in T2DM. TRPMs, located on the PM, are crucial for sensory physiology. Members of the TRPM family are extensively expressed in the islet β cells, heart, and kidneys. The TRPM family comprises eight members, and only TRPM4 and 5 are not calcium-permeable. However, TRPM4 and 5 can be activated by intracellular calcium accumulation. The subunits of TRPM members consist of a substantial number of amino acids, rendering them the largest proteins within the TRP superfamily. TRPM members interact with calmodulin, a calcium-binding protein, controls calcium homeostasis[83]. They are generally composed of six transmembrane helical domains with a conserved calcium-binding site[84]. TRPM members have been implicated in various physiological processes[85]. For example, TRPM1 plays a pivotal role in melanin metabolism, TRPM2 serves as a crucial factor in oxidative stress-induced cell death, TRPM3 is implicated in the pathogenesis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma, TRPM4 has the potential to enhance interleukin-2 production, TRPM5 is involved in the development of T2DM, both TRPM6 and TRPM7 modulate the response to sepsis, and TRPM8 is a clinical target for prostate cancer treatment[86]. Here, we focus on their potential association with AMPK and T2DM.

TRPM2, TRPM3, and TRPM7 are associated with AMPK activation. Silencing TRPM2 leads to a decrease in ATP levels and activates AMPK. In TRPM2 knockout cells, abscisic acid-mediated AMPK activation improves glucose uptake and is independent of the insulin pathway[87]. In contrast, activation of TRPM3 and TRPM7 induces intracellular calcium accumulation, thereby enhancing the phosphorylation levels of CaMKKβ and AMPK[88,89]. Clotrimazole and glibenclamide (inhibitors of TRPM4) inhibit AMPK-mediated muscle cell hyperpolarization[90]. Additionally, TRPM2, TRPM4, and TRPM5 regulate insulin secretion by perceiving the intracellular calcium levels (Table 2)[91]. Currently, TRPMs are reported to induce AMPK activation; however, further investigation is required to elucidate whether TRPM-mediated AMPK activation causes adverse reactions in the treatment of T2DM.

Targeting calcium channels in the treatment of T2DM is promising (Figure 2). However, there are still many challenges to overcome: (1) The structures and functions of these channels remain elusive; (2) Highly specific agonists and inhibitors are not available for many of these channels; (3) Agonists and inhibitors of these channels exhibit cytotoxicity, and thus require further development; and (4) When more than one calcium channel is present on the same organelle, how these channels work remains unclear. Therefore, developing efficient and non-toxic agonists and inhibitors for these channels is imperative. Additionally, extensive research is required to elucidate the structure and function of other ion channels.

In this review, we summarize 15 calcium ion channels that could be potential targets for T2DM treatment via AMPK (Figure 2). Among them, seven (VDAC1, MCU, SERCA, TRPV1, TRPML1, TRPM3, and TRPM7) have been specifically reported to be associated with AMPK activation. VDAC1 and MCU activate AMPK through the energy-sensing mechanism, while SERCA, TRPV1, TRPML1, TRPM3, and TRPM7 activate AMPK through calcium signaling. Moreover, TRPV1, SERCA, and TRPML1 have already been proven to activate AMPK and alleviate the phenotype of T2DM. In addition, there are other ion channels, such as potassium ion channels, that reportedly play a role in the treatment of T2DM[92]. Since this is not the focus of this article, we have not discussed these channels in this review. In summary, targeting calcium-permeable channels is a very promising direction in the exploration of new drugs for T2DM, but extensive studies are required in this field.

| 1. | Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3033] [Cited by in RCA: 4791] [Article Influence: 1597.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 2. | DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E, Groop L, Henry RR, Herman WH, Holst JJ, Hu FB, Kahn CR, Raz I, Shulman GI, Simonson DC, Testa MA, Weiss R. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 865] [Cited by in RCA: 1323] [Article Influence: 132.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Saltiel AR. Insulin signaling in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e142241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 61.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | van Netten JJ, Bus SA, Apelqvist J, Lipsky BA, Hinchliffe RJ, Game F, Rayman G, Lazzarini PA, Forsythe RO, Peters EJG, Senneville É, Vas P, Monteiro-Soares M, Schaper NC; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. Definitions and criteria for diabetic foot disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36 Suppl 1:e3268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Packer M. Differential Pathophysiological Mechanisms in Heart Failure With a Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction in Diabetes. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9:535-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhu J, Hu Z, Luo Y, Liu Y, Luo W, Du X, Luo Z, Hu J, Peng S. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: pathogenetic mechanisms and treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1265372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yuan Y, Kong F, Xu H, Zhu A, Yan N, Yan C. Cryo-EM structure of human glucose transporter GLUT4. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Roberts CK, Hevener AL, Barnard RJ. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: underlying causes and modification by exercise training. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:1-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huang X, Liu G, Guo J, Su Z. The PI3K/AKT pathway in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14:1483-1496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 1013] [Article Influence: 144.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hsu HC, Chen SY, Huang YC, Wang RH, Lee YJ, An LW. Decisional Balance for Insulin Injection: Scale Development and Psychometric Testing. J Nurs Res. 2019;27:e42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bhatt HB. Thoughts on the progression of type 2 diabetes drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2015;10:107-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ahrén B. DPP-4 inhibitors. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;21:517-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Padhi S, Nayak AK, Behera A. Type II diabetes mellitus: a review on recent drug based therapeutics. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;131:110708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 55.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ruscica M, Baldessin L, Boccia D, Racagni G, Mitro N. Non-insulin anti-diabetic drugs: An update on pharmacological interactions. Pharmacol Res. 2017;115:14-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Garcia-Ropero A, Badimon JJ, Santos-Gallego CG. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of SGLT2 inhibitors for type 2 diabetes mellitus: the latest developments. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2018;14:1287-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | González A, Hall MN, Lin SC, Hardie DG. AMPK and TOR: The Yin and Yang of Cellular Nutrient Sensing and Growth Control. Cell Metab. 2020;31:472-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 102.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | O'Donnell AF, Schmidt MC. AMPK-Mediated Regulation of Alpha-Arrestins and Protein Trafficking. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Huang S, Liang H, Chen Y, Liu C, Luo P, Wang H, Du Q. Hypoxanthine ameliorates diet-induced insulin resistance by improving hepatic lipid metabolism and gluconeogenesis via AMPK/mTOR/PPARα pathway. Life Sci. 2024;357:123096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim J, Yang G, Kim Y, Kim J, Ha J. AMPK activators: mechanisms of action and physiological activities. Exp Mol Med. 2016;48:e224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 553] [Article Influence: 61.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ma T, Tian X, Zhang B, Li M, Wang Y, Yang C, Wu J, Wei X, Qu Q, Yu Y, Long S, Feng JW, Li C, Zhang C, Xie C, Wu Y, Xu Z, Chen J, Yu Y, Huang X, He Y, Yao L, Zhang L, Zhu M, Wang W, Wang ZC, Zhang M, Bao Y, Jia W, Lin SY, Ye Z, Piao HL, Deng X, Zhang CS, Lin SC. Low-dose metformin targets the lysosomal AMPK pathway through PEN2. Nature. 2022;603:159-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 112.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Thiazolidinediones in the treatment of insulin resistance and type II diabetes. Diabetes. 1996;45:1661-1669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 526] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Salani B, Ravera S, Fabbi P, Garibaldi S, Passalacqua M, Brunelli C, Maggi D, Cordera R, Ameri P. Glibenclamide Mimics Metabolic Effects of Metformin in H9c2 Cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43:879-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pfeiffer AF, Klein HH. The treatment of type 2 diabetes. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:69-81; quiz 82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | D'Elia JA, Segal AR, Bayliss GP, Weinrauch LA. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition and acidosis in patients with type 2 diabetes: a review of US FDA data and possible conclusions. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:153-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aguilar D. Management of type 2 diabetes in patients with heart failure. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2008;10:465-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Peter PR, Lupsa BC. Personalized Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19:115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Umeda T, Minami T, Bartolomei K, Summerhill E. Metformin-Associated Lactic Acidosis: A Case Report. Drug Saf Case Rep. 2018;5:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Perrone J, Phillips C, Gaieski D. Occult metformin toxicity in three patients with profound lactic acidosis. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:271-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Krasner NM, Ido Y, Ruderman NB, Cacicedo JM. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analog liraglutide inhibits endothelial cell inflammation through a calcium and AMPK dependent mechanism. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Palmer KJ, Brogden RN. Gliclazide. An update of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 1993;46:92-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Feng WH, Bi Y, Li P, Yin TT, Gao CX, Shen SM, Gao LJ, Yang DH, Zhu DL. Effects of liraglutide, metformin and gliclazide on body composition in patients with both type 2 diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized trial. J Diabetes Investig 2019. 10:399-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Xie Z, Yang S, Deng W, Li J, Chen J. Efficacy and Safety of Liraglutide and Semaglutide on Weight Loss in People with Obesity or Overweight: A Systematic Review. Clin Epidemiol. 2022;14:1463-1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Feng X, Yuan L, Hu Y, Zhu Y, Yang F, Jiang L, Yan R, Luo Y, Zhao E, Liu C, Wang Y, Li Q, Cao X, Li Q, Ma J. Gliclazide-Induced Insulin Autoimmune Syndrome: A Rare Case Report and Review on Literature. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2016;16:230-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bajaj S, Ong ST, Chandy KG. Contributions of natural products to ion channel pharmacology. Nat Prod Rep. 2020;37:703-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Messina A, Reina S, Guarino F, De Pinto V. VDAC isoforms in mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:1466-1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Rosencrans WM, Rajendran M, Bezrukov SM, Rostovtseva TK. VDAC regulation of mitochondrial calcium flux: From channel biophysics to disease. Cell Calcium. 2021;94:102356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hwang HY, Shim JS, Kim D, Kwon HJ. Antidepressant drug sertraline modulates AMPK-MTOR signaling-mediated autophagy via targeting mitochondrial VDAC1 protein. Autophagy. 2021;17:2783-2799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhang E, Mohammed Al-Amily I, Mohammed S, Luan C, Asplund O, Ahmed M, Ye Y, Ben-Hail D, Soni A, Vishnu N, Bompada P, De Marinis Y, Groop L, Shoshan-Barmatz V, Renström E, Wollheim CB, Salehi A. Preserving Insulin Secretion in Diabetes by Inhibiting VDAC1 Overexpression and Surface Translocation in β Cells. Cell Metab. 2019;29:64-77.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Liu C, Li HJ, Duan WX, Duan Y, Yu Q, Zhang T, Sun YP, Li YY, Liu YS, Xu SC. MCU Upregulation Overactivates Mitophagy by Promoting VDAC1 Dimerization and Ubiquitination in the Hepatotoxicity of Cadmium. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10:e2203869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | D'Angelo D, Rizzuto R. The Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter (MCU): Molecular Identity and Role in Human Diseases. Biomolecules. 2023;13:1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Tomar D, Jaña F, Dong Z, Quinn WJ 3rd, Jadiya P, Breves SL, Daw CC, Srikantan S, Shanmughapriya S, Nemani N, Carvalho E, Tripathi A, Worth AM, Zhang X, Razmpour R, Seelam A, Rhode S, Mehta AV, Murray M, Slade D, Ramirez SH, Mishra P, Gerhard GS, Caplan J, Norton L, Sharma K, Rajan S, Balciunas D, Wijesinghe DS, Ahima RS, Baur JA, Madesh M. Blockade of MCU-Mediated Ca(2+) Uptake Perturbs Lipid Metabolism via PP4-Dependent AMPK Dephosphorylation. Cell Rep. 2019;26:3709-3725.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Luo D, Zhao Y, Fang Z, Zhao Y, Han Y, Piao J, Rong X, Guo J. Tianhuang formula regulates adipocyte mitochondrial function by AMPK/MICU1 pathway in HFD/STZ-induced T2DM mice. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2023;23:202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Diaz-Juarez J, Suarez J, Cividini F, Scott BT, Diemer T, Dai A, Dillmann WH. Expression of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter in cardiac myocytes improves impaired mitochondrial calcium handling and metabolism in simulated hyperglycemia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016;311:C1005-C1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Scorziello A, Savoia C, Sisalli MJ, Adornetto A, Secondo A, Boscia F, Esposito A, Polishchuk EV, Polishchuk RS, Molinaro P, Carlucci A, Lignitto L, Di Renzo G, Feliciello A, Annunziato L. NCX3 regulates mitochondrial Ca(2+) handling through the AKAP121-anchored signaling complex and prevents hypoxia-induced neuronal death. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:5566-5577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Roy S, Dey K, Hershfinkel M, Ohana E, Sekler I. Identification of residues that control Li(+) versus Na(+) dependent Ca(2+) exchange at the transport site of the mitochondrial NCLX. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2017;1864:997-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Nikolaeva MA, Mukherjee B, Stys PK. Na+-dependent sources of intra-axonal Ca2+ release in rat optic nerve during in vitro chemical ischemia. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9960-9967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Pizzo P, Drago I, Filadi R, Pozzan T. Mitochondrial Ca²⁺ homeostasis: mechanism, role, and tissue specificities. Pflugers Arch. 2012;464:3-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Chambers PJ, Juracic ES, Fajardo VA, Tupling AR. Role of SERCA and sarcolipin in adaptive muscle remodeling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2022;322:C382-C394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Toyoshima C, Nomura H, Tsuda T. Lumenal gating mechanism revealed in calcium pump crystal structures with phosphate analogues. Nature. 2004;432:361-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Tada M, Yamamoto T, Tonomura Y. Molecular mechanism of active calcium transport by sarcoplasmic reticulum. Physiol Rev. 1978;58:1-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Samuel TJ, Rosenberry RP, Lee S, Pan Z. Correcting Calcium Dysregulation in Chronic Heart Failure Using SERCA2a Gene Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Zhihao L, Jingyu N, Lan L, Michael S, Rui G, Xiyun B, Xiaozhi L, Guanwei F. SERCA2a: a key protein in the Ca(2+) cycle of the heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2020;25:523-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Zarain-Herzberg A, García-Rivas G, Estrada-Avilés R. Regulation of SERCA pumps expression in diabetes. Cell Calcium. 2014;56:302-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Shi W, Xu D, Gu J, Xue C, Yang B, Fu L, Song S, Liu D, Zhou W, Lv J, Sun K, Chen M, Mei C. Saikosaponin-d inhibits proliferation by up-regulating autophagy via the CaMKKβ-AMPK-mTOR pathway in ADPKD cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2018;449:219-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Guerrero-Hernández A, Sánchez-Vázquez VH, Martínez-Martínez E, Sandoval-Vázquez L, Perez-Rosas NC, Lopez-Farias R, Dagnino-Acosta A. Sarco-Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Release Model Based on Changes in the Luminal Calcium Content. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1131:337-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Zhang X, Huang R, Zhou Y, Zhou W, Zeng X. IP3R Channels in Male Reproduction. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:9179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Woll KA, Van Petegem F. Calcium-release channels: structure and function of IP(3) receptors and ryanodine receptors. Physiol Rev. 2022;102:209-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Santulli G, Pagano G, Sardu C, Xie W, Reiken S, D'Ascia SL, Cannone M, Marziliano N, Trimarco B, Guise TA, Lacampagne A, Marks AR. Calcium release channel RyR2 regulates insulin release and glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Haustrate A, Prevarskaya N, Lehen'kyi V. Role of the TRPV Channels in the Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Homeostasis. Cells. 2020;9:317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Kärki T, Tojkander S. TRPV Protein Family-From Mechanosensing to Cancer Invasion. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Liu C, Xue L, Song C. Calcium binding and permeation in TRPV channels: Insights from molecular dynamics simulations. J Gen Physiol. 2023;155:e202213261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Rosenbaum T, Islas LD. Molecular Physiology of TRPV Channels: Controversies and Future Challenges. Annu Rev Physiol. 2023;85:293-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Bevan S, Quallo T, Andersson DA. TRPV1. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;222:207-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Li M, Zhang CS, Zong Y, Feng JW, Ma T, Hu M, Lin Z, Li X, Xie C, Wu Y, Jiang D, Li Y, Zhang C, Tian X, Wang W, Yang Y, Chen J, Cui J, Wu YQ, Chen X, Liu QF, Wu J, Lin SY, Ye Z, Liu Y, Piao HL, Yu L, Zhou Z, Xie XS, Hardie DG, Lin SC. Transient Receptor Potential V Channels Are Essential for Glucose Sensing by Aldolase and AMPK. Cell Metab. 2019;30:508-524.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Li X, Hou J, Du J, Feng J, Yang Y, Shen Y, Chen S, Feng J, Yang D, Li D, Pei H, Yang Y. Potential Protective Mechanism in the Cardiac Microvascular Injury. Hypertension. 2018;72:116-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Xu S, Liang S, Pei Y, Wang R, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Huang B, Li H, Li J, Tan B, Cao H, Guo S. TRPV1 Dysfunction Impairs Gastric Nitrergic Neuromuscular Relaxation in High-Fat Diet-Induced Diabetic Gastroparesis Mice. Am J Pathol. 2023;193:548-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Wang T, Chen Y, Li Y, Wang Z, Qiu C, Yang D, Chen K. TRPV1 Protect against Hyperglycemia and Hyperlipidemia Induced Liver Injury via OPA1 in Diabetes. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2022;256:131-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Vahidi Ferdowsi P, Ahuja KDK, Beckett JM, Myers S. TRPV1 Activation by Capsaicin Mediates Glucose Oxidation and ATP Production Independent of Insulin Signalling in Mouse Skeletal Muscle Cells. Cells. 2021;10:1560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zhu SL, Wang ML, He YT, Guo SW, Li TT, Peng WJ, Luo D. Capsaicin ameliorates intermittent high glucose-mediated endothelial senescence via the TRPV1/SIRT1 pathway. Phytomedicine. 2022;100:154081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Maeda A, Shirao T, Shirasaya D, Yoshioka Y, Yamashita Y, Akagawa M, Ashida H. Piperine Promotes Glucose Uptake through ROS-Dependent Activation of the CAMKK/AMPK Signaling Pathway in Skeletal Muscle. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018;62:e1800086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Wu R, Jian T, Ding X, Lv H, Meng X, Ren B, Li J, Chen J, Li W. Total Sesquiterpene Glycosides from Loquat Leaves Ameliorate HFD-Induced Insulin Resistance by Modulating IRS-1/GLUT4, TRPV1, and SIRT6/Nrf2 Signaling Pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:4706410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Wang P, Yan Z, Zhong J, Chen J, Ni Y, Li L, Ma L, Zhao Z, Liu D, Zhu Z. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 activation enhances gut glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion and improves glucose homeostasis. Diabetes. 2012;61:2155-2165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Fine M, Li X. A Structural Overview of TRPML1 and the TRPML Family. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2023;278:181-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Di Paola S, Scotto-Rosato A, Medina DL. TRPML1: The Ca((2+))retaker of the lysosome. Cell Calcium. 2018;69:112-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Wang W, Zhang X, Gao Q, Xu H. TRPML1: an ion channel in the lysosome. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;222:631-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Spix B, Chao YK, Abrahamian C, Chen CC, Grimm C. TRPML Cation Channels in Inflammation and Immunity. Front Immunol. 2020;11:225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Scotto Rosato A, Montefusco S, Soldati C, Di Paola S, Capuozzo A, Monfregola J, Polishchuk E, Amabile A, Grimm C, Lombardo A, De Matteis MA, Ballabio A, Medina DL. TRPML1 links lysosomal calcium to autophagosome biogenesis through the activation of the CaMKKβ/VPS34 pathway. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Wu LK, Agarwal S, Kuo CH, Kung YL, Day CH, Lin PY, Lin SZ, Hsieh DJ, Huang CY, Chiang CY. Artemisia Leaf Extract protects against neuron toxicity by TRPML1 activation and promoting autophagy/mitophagy clearance in both in vitro and in vivo models of MPP+/MPTP-induced Parkinson's disease. Phytomedicine. 2022;104:154250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Gan N, Jiang Y. Structural biology of cation channels important for lysosomal calcium release. Cell Calcium. 2022;101:102519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Kintzer AF, Stroud RM. On the structure and mechanism of two-pore channels. FEBS J. 2018;285:233-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Grimm C, Chen CC, Wahl-Schott C, Biel M. Two-Pore Channels: Catalyzers of Endolysosomal Transport and Function. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Pereira GJ, Antonioli M, Hirata H, Ureshino RP, Nascimento AR, Bincoletto C, Vescovo T, Piacentini M, Fimia GM, Smaili SS. Glutamate induces autophagy via the two-pore channels in neural cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:12730-12740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Vydra Bousova K, Zouharova M, Jiraskova K, Vetyskova V. Interaction of Calmodulin with TRPM: An Initiator of Channel Modulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:15162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Souza Bomfim GH, Niemeyer BA, Lacruz RS, Lis A. On the Connections between TRPM Channels and SOCE. Cells. 2022;11:1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Zhang M, Ma Y, Ye X, Zhang N, Pan L, Wang B. TRP (transient receptor potential) ion channel family: structures, biological functions and therapeutic interventions for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Jimenez I, Prado Y, Marchant F, Otero C, Eltit F, Cabello-Verrugio C, Cerda O, Simon F. TRPM Channels in Human Diseases. Cells. 2020;9:2604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Magnone M, Emionite L, Guida L, Vigliarolo T, Sturla L, Spinelli S, Buschiazzo A, Marini C, Sambuceti G, De Flora A, Orengo AM, Cossu V, Ferrando S, Barbieri O, Zocchi E. Insulin-independent stimulation of skeletal muscle glucose uptake by low-dose abscisic acid via AMPK activation. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | He J, Wang P, Wang Z, Feng D, Zhang D. TRPM7-Mediated Ca(2+) Regulates Mussel Settlement through the CaMKKβ-AMPK-SGF1 Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:5399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Hall DP, Cost NG, Hegde S, Kellner E, Mikhaylova O, Stratton Y, Ehmer B, Abplanalp WA, Pandey R, Biesiada J, Harteneck C, Plas DR, Meller J, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF. TRPM3 and miR-204 establish a regulatory circuit that controls oncogenic autophagy in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:738-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Weston AH, Egner I, Dong Y, Porter EL, Heagerty AM, Edwards G. Stimulated release of a hyperpolarizing factor (ADHF) from mesenteric artery perivascular adipose tissue: involvement of myocyte BKCa channels and adiponectin. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:1500-1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Uchida K, Tominaga M. The role of thermosensitive TRP (transient receptor potential) channels in insulin secretion. Endocr J. 2011;58:1021-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Dahlén AD, Dashi G, Maslov I, Attwood MM, Jonsson J, Trukhan V, Schiöth HB. Trends in Antidiabetic Drug Discovery: FDA Approved Drugs, New Drugs in Clinical Trials and Global Sales. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:807548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |