Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.96176

Revised: October 1, 2024

Accepted: January 13, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 305 Days and 18.9 Hours

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is linked to an earlier onset and heightened severity of urinary complications, particularly bladder dysfunction, which profoundly im

To clarify the mechanism of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) metabolic surgery to improve OAB in type 2 DM (T2DM).

The model of T2DM was induced by feeding a high-fat diet to mice for 16 weeks. After 16 weeks, sham operation and RYGB operation were performed. The related indexes of glucose metabolism were also detected to evaluate the therapeutic effect, and the recovery degree of bladder function and micturition behavior of mice was assessed by urodynamics and micturition spot analysis.

Compared with the normal mice in the sham group, T2DM mice had increased urine spot count, uncontrolled urination behavior, shortened urination interval, and reduced bladder capacity. Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence costaining showed that Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) and purinergic receptor P2X3 were both expressed in mouse bladder epithelial layer, and they had the same localization. In the bladder of T2DM mice, the mRNA and protein expression of TRPV1 and P2X3 were significantly increased. The ATP content in urine of T2DM mice was significantly higher than that of the sham group. After RYGB operation, the glucose metabolism index of the RYGB group was significantly improved compared with the OAB group. Comparing the results of urine spots, urodynamics, and histology, it was found that the function and morphological structure of the bladder in the RYGB group also recovered obviously. Compared with the OAB group, the expression of TRPV1 and P2X3 in the RYGB group was downregulated, and the level of inflammatory factors was significantly decreased. RYGB significantly decreased the content of ATP in urine and activated AMPK signaling.

RYGB downregulated the expression of TRPV1 by inhibiting inflammatory factors, thus inhibiting the en

Core Tip: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as a metabolic surgery, effectively alleviates complications associated with diabetes. Although the mechanisms underlying diabetes-induced overactive bladder remain unclear, this study found that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass improved overactive bladder symptoms by suppressing inflammatory cytokines, reducing transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 expression, and inhibiting ATP synthesis in bladder epithelial cells, ultimately leading to a direct inhibition of purinergic receptor P2X3 activity.

- Citation: Li GY, Ren S, Huang BC, Feng JJ, Wang QQ, Peng QJ, Tian HF, Yu LY, Ma CL, Fan SZ, Chen XJ, Al-Qaisi MA, He R. Role and mechanism of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the treatment of diabetic urinary bladder hyperactivity by reducing TRPV1 and P2X3. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(4): 96176

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i4/96176.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.96176

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has been associated with an earlier onset and increased severity of urologic diseases that often results in debilitating urologic complications. These urologic complications include bladder dysfunction[1] and have a profound effect on the quality of life for patients with DM. Diabetic bladder dysfunction, which encompasses a broad spectrum of symptoms ranging from detrusor overactivity or hypersensitivity to impaired bladder contractility[2], has received far less attention than other diabetic complications. Overactive bladder (OAB) is a common lower urinary tract (LUT) storage disorder characterized by urinary urgency. Specifically, patients experience a sudden, uncontrollable urge to urinate, often accompanied by increased urinary frequency and nocturia in patients with DM[3,4]. Many factors can potentially affect bladder function and contribute to OAB, including urothelial signaling mechanisms, changes in detrusor morphology and innervation, intercellular communication and electrical properties, detrusor receptors, and central nervous regulation of the micturition process[5]. Research has focused mainly on detrusor smooth muscle, bladder vasculature, and innervation, whereas the physiological impact of DM on the urothelium (UT) (epithelial lining of the urinary bladder) is largely unknown[6].

Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) is a nonselective cation channel that may be activated by a wide variety of exogenous and endogenous physical and chemical stimuli[7]. TRPV1 can be expressed in non-neuronal tissues such as bladder urothelial cells, and urothelial TRPV1 expression is increased in OAB[7,8]. There is electrophysiologic evidence for increased TRPV1 channel activity in OAB cells[9]. The increased TRPV1 activity is associated with increased ATP release, but the underlying mechanism remains unclear[10]. During bladder filling, the UT is stretched, and ATP is released from the umbrella cells, thereby activating mechano-transduction pathways via stimulation of purinergic (P2X) receptors on suburothelial sensory nerves to initiate the voiding reflex and to mediate the sensation of bladder filling and urgency[11,12]. The purinergic receptors, particularly P2X3, have been of interest for treatment of LUT disorders for a long time[13-15]. Based on the above evidence, it can be found that TRPV1 may release ATP by regulating bladder epithelial expansion, thus activating P2X3 activity and promoting OAB.

On the other hand, metabolic/bariatric surgery is currently the most effective treatment for obesity, providing profound, sustained weight loss and improvement or resolution of obesity-related comorbidities[16]. By 2019, the most frequently performed metabolic procedures were sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, and biliopancreatic shunt with duodenal transposition[17]. It is now recognized that most currently performed metabolic procedures improve obesity and its comorbidities (including type 2 DM [T2DM]) through pacloblastic effects on intestinal physiology, transcriptional programs in intestinal differentiation programs, neuronal signaling, intestinal proinsulin hormone secretion, bile acid metabolism, lipid regulation, microbiota changes, and glucose homeostasis[17,18]. Therefore, there is a growing number of studies demonstrating metabolic surgery can be a safe, effective, and durable treatment for both obesity and T2DM[19,20]. Remission rates for T2DM declined over the last 5 years of the study but were greatest for RYGB[18].

In RYGB, a small stomach pouch is divided from the remainder of the stomach, which remains in situ and in continuity with the duodenum[21]. These anatomic changes lead to alterations in the signaling between luminal factors and the intestinal mucosa, thus generating neurohumoral effects that further lead to alterations in hunger, satiety, energy balance, modest fat malabsorption, and weight loss[22]. The beneficial effects of RYGB surgery on DM remission were recognized by surgeons from the early days of using this approach for weight loss in patients with class III obesity[23]. Therefore, RYGB is recognized as one of the most effective methods for treating and remitting long-term DM[24]. At present, the exact mechanism of RYGB in improving DM and related complications has not been clarified. In this study, RYGB metabolic surgery was performed on experimentally-induced T2DM mice and explored part of the mechanism of RYGB improving T2DM-related OAB.

This study was reviewed by the Ethical Review Committee of Ningxia Medical University (IACUC-NYLAC-2021-054). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics guidelines and regulations and complied with the ARRIVE guidelines. A total of 24 male C57/6J mice (6 weeks of age) were housed in pathogen-free conditions (room temperature 22 °C, humidity 50%-60%) with free access to food and water, and a 12:12 light/dark cycle was followed periodically. All mice were paired at similar body weights and then randomized to a control group (n = 8) and a sham group (n = 16). The sham group was fed a high-fat diet (HFD) for 16 weeks (cat. No. D 12492, United States, Research Diets General Nutrition, with 20%, 20%, and 60% protein, carbohydrate, and fat, respectively). The control group was fed an ordinary diet (Pluton Biotechnology Co, Ltd) for the same period. For metabolic surgery, the sham mice were paired according to body weight into sham (n = 8) and RYGB (n = 8) groups. After surgery, the OAB group and RYGB group were fed a HFD for 4 weeks until the conclusion of the experiment.

Mice in the RYGB group were fasted for 4-6 h prior to the start of surgery and the entire procedure was performed in a sterile environment. Firstly, mice were anesthetized and stomach exposed. Perigastric ligaments were ligated and cut to release the stomach. The left gastric vessel was separated bluntly from the cardia to make room for pouch operation without impairing the gastric blood supply. A titanium clip was applied to generate a small pouch size of about 5% of the total stomach volume. The stomach was transected right above the clip, leaving the left gastric vessels intact. Jejunum was transected about 2 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. The small gastric pouch was then anastomosed to the cut end of the jejunum using 11-0 nylon suture in an uninterrupted suture fashion. For the jejuno-jejunostomy, a longitudinal slit was made on the anti-mesenteric side of the jejunum at 6 cm distal to the site of gastrojejunostomy, and the proximal end of the jejunum was joined in an end-to-side anastomosis using 11-0 nylon suture in an uninterrupted fashion. This resulted in a common limb consisting of the distal jejunum and the ileum of about 12 cm, a Roux limb about 5-6 cm, and a biliopancreatic limb about 5-6 cm. In the abdominal wall, the muscular layer and skin were closed using interrupted 6-0 nylon suture and interrupted 5-0 nylon suture, respectively[25].

For the sham operation, the mice in the sham group were anesthetized under sterile conditions to open the abdominal cavity (the same procedure as RYGB) and the stomach was released, separating the left trachea from the cardia. The stomach, esophagus, and small intestine were exposed, and the abdominal cavity was closed with intermittent suture[23].

Prior to surgery, body weights were measured and recorded weekly for all mice starting at 6 weeks of age and pro

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and insulin tolerance test (ITT) were performed when the mice were fed for 16 weeks. Prior to the OGTT, mice were fasted for approximately 16 h. A small wound was cut at the tip of the mouse tail with scis

Individual mice were transferred to clean, empty cages lined with filter paper. Unless otherwise noted, determinations were made for more than 4 h with food rather than water obtained at the same quiet location and time. The filter paper was imaged with UV light and analyzed using Image J software. Thresholding of the image was performed in Image J to darken the urine point. Image J particle analysis (ImageJ 1.46 r) was performed on spots greater than 0.02 cm2 (equivalent to 0.75 mL of urine) and reduced the potential for non-specific markers to be deposited by the paw and tail of the urine spots. The raw images of the urine spots were analyzed by Image J, and the following parameters were collected, including the number of urine spots (assessing the frequency of urination), the total area of the urine spots (reflecting the volume of urine), and the percentage of the urine spots in the central area.

For cystometry experiments, 25% ethyl carbamate (1.8 g/kg, via intraperitoneal injection; Sigma Chemicals) was ad

Bladder tissue was immersed in neutral buffered formalin containing 4% formaldehyde for 4 h and subsequently embedded in paraffin. A 5-μm thick section was obtained using a rotary microtome. The sections were then stained following standard protocols for hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome staining.

For H&E staining, the tissue sections were cleared with xylene and alcohol, immersed in hematoxylin dye solution for 4 min, and rinsed with clean water for 2 s to differentiate. They were then rinsed with 1% hydrochloric acid alcohol, stained with eosin for 2 min, washed with clear water, dehydrated using increasing concentrations of ethanol, and finally cleared with xylene before mounting.

For Masson’s trichromatic staining, tissue sections were incubated for 5 min in Masson counterstaining solution, rinsed, and stained in phosphomolybdic acid for 5 min. Next, the sections were stained with bright green dye for 10 min, rinsed in acetic acid for 2 min, and in distilled water twice for 2 min. Finally, the sections were dehydrated by increasing the ethanol concentration, air dried, and fixed. The images of the tissue sections were captured with a digital camera and analyzed with Image Pro Plus software.

For immunohistochemistry, the bladder stone paraffin sections were deparaffinized and dehydrated with xylene and ethanol. After PBS moistening and washing, the sections were put into citric acid buffer and heated with high fire for 3 min and low fire for 7 min in the microwave oven for tissue antigen repair. The sections were treated with a peroxidase blocker for 20 min, followed by washing with PBS. They were then blocked with goat serum for 1 h. The primary antibody was added dropwise for incubation overnight and reacted the next day with an enzyme-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG for 20 min. After washing with PBS, DAB developing solution (diluted to 1:20) was added dropwise for observation under the microscope. After staining, PBS buffer was added to stop the reaction. After staining the sections with hematoxylin to visualize the nuclei, they were dehydrated and cleared following the dehydration protocol, and finally the sections were sealed. After drying, the samples were observed under a microscope.

For immunofluorescence costaining, the bladder stone paraffin sections were deparaffinized and dehydrated with xylene and ethanol. After natural cooling, 0.1%Triton X-100 was dropwise added onto the tissues to rupture the mem

Protein samples were prepared from bladder tissue homogenates using RIPA lysis buffer. The concentration was subsequently determined using a BCA protein assay kit. An equal mass of protein (30 μg/lane) was separated by electrophoresis on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to PVDF membrane. Western blot was performed with antibodies against TRPV1, P2X3, nuclear factor (NF)-κB, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), p-AMPK, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), p-mTOR, β-actin, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Table 1). The results of the western blot were normalized with β-actin/GAPDH and analyzed by ImageJ.

| Antibody | Source | Catalogue number | Dilution |

| TRPV1 | Bioss | bs-23926R | 1:800 (Wb); 1:500 (IHC, IF) |

| P2X3 | Santa Cruz | sc-390572 | 1:1000 (Wb); 1:500 (IHC, IF) |

| NF-κB | ABclonal | A18210 | 1:1000 (Wb) |

| IL-1β | Affinity | AF5103 | 1:1000 (Wb) |

| IL-6 | Affinity | DF6087 | 1:1000 (Wb) |

| TNF-α | ABclonal | A0277 | 1:1000 (Wb) |

| p-mTOR | Cell signaling technology | 2971 | 1:1000 (Wb) |

| mTOR | Cell signaling technology | 2983 | 1:1000 (Wb) |

| p-AMPK | Cell signaling technology | 2535 | 1:1000 (Wb) |

| AMPK | Cell signaling technology | 2532 | 1:1000 (Wb) |

| GAPDH | Wanleibio | WL01114 | 1:2000 (Wb) |

| β-actin | Santa Cruz | sc-47778 | 1:2000 (Wb) |

For gene expression analyses, total RNA from the bladder tissue was isolated by TRIZOL reagent and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a real time (RT)-PCR kit (TaKaRa). The synthesized cDNA was amplified via quantitative RT-PCR on an ABI Prism 7500 system using SYBR Green RT-PCR MasterMix reagent. Sequences for the primer pairs used in this study are listed in Table 2. Gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method and normalized to GAPDH expression in each sample[26].

| Primer name | Primers (5’-3’) | Gengray ID |

| TRPV1 | GTTTACCTCGTCCACCCTGA (forward) | 220629I42 |

| AGAGAGCCATVACCATCCTG (reverse) | 220629I43 | |

| P2X3 | TCTCCAGCAGAGACATCAGCA (forward) | 220629I44 |

| GGGAGCATCTTGGTGAACTCAG (reverse) | 220629I45 | |

| β-actin | CATCCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCCAAC (forward) | 220629I38 |

| ATGGAGCCACCGATCCACA (reverse) | 220629I39 |

Graph Pad Prism 9.0 software was used to analyze the experimental results. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance was used for comparison of means between groups, and the Dunnett test was used for pairwise comparison of homogeneity of variance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Prior to treatment, the body weights of OAB mice induced by an HFD were significantly higher than those in the sham group. After RYGB surgical treatment, the body weights of the mice significantly decreased and gradually normalized to normal mice (Figure 1A). The glucose tolerance of the RYGB-treated mice was improved compared with that of the OAB mice (Figure 1B and C). In addition, the impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance of the RYGB-treated mice were significantly relieved (Figure 1D and E).

OAB mice showed abnormal urination, including abnormal urination behavior and increased frequency of urine excretion. The urination behavior was mainly by observing the location of urine spots in the void spot assay, and the frequency of urine excretion could be used to observe the number of urine spots (Figure 2A). Within 4 h, the urine volume and frequency of urine excretion of HFD-induced OAB mice were significantly increased, and the urine spot area in the central region was significantly increased. After RYGB treatment, the frequency of urine excretion of the mice was decreased (Figure 2B), the urine volume within 4 h was decreased (Figure 2C), and the urine spot area in the central region was decreased (Figure 2D).

The urodynamic experiments can well reflect the parameters related to bladder function, such as frequency of urination discharge, bladder capacity, and peak urination contraction pressure of the bladder (Figure 3A-C). Compared with the OAB group, the RYGB-treated mice had significantly reduced urination contractions (Figure 3D), significantly reduced number of non-urination contractions (Figure 3E), significantly increased bladder capacity (Figure 3F), and decreased peak maximum urination pressure (Figure 3G).

H&E staining (Figure 4A) showed that the folds of the bladder epithelium in the sham group were obvious and arranged closely, and the thicknesses of the mucosal lamina propria and migrating epithelial cell layers were normal. In the OAB group, the folds of the bladder epithelium were reduced, and the thickness of the mucosal lamina propria became thinner. Compared with the OAB group, the RYGB-treated mice showed recovery of epithelial fold structures and thickening of the lamina propria, but there were no significant changes in the thickness of the migratory epithelium in the three groups (Figure 4B).

Masson’s trichrome staining results (Figure 4C) showed a significant increase in collagen fiber content in the bladder muscle layer of OAB mice, and a significant decrease in the fiber content in the bladder muscle layer of the RYGB-treated mice compared with the OAB group (Figure 4D). To further clarify the changes in the muscle composition of bladder tissue, western blot was used to detect the content of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in bladder tissue (Figure 4E). The results showed that α-SMA content in bladder tissue of HFD mice was significantly increased, while α-SMA content in bladder tissue of RYGB-treated mice was significantly decreased (Figure 4F).

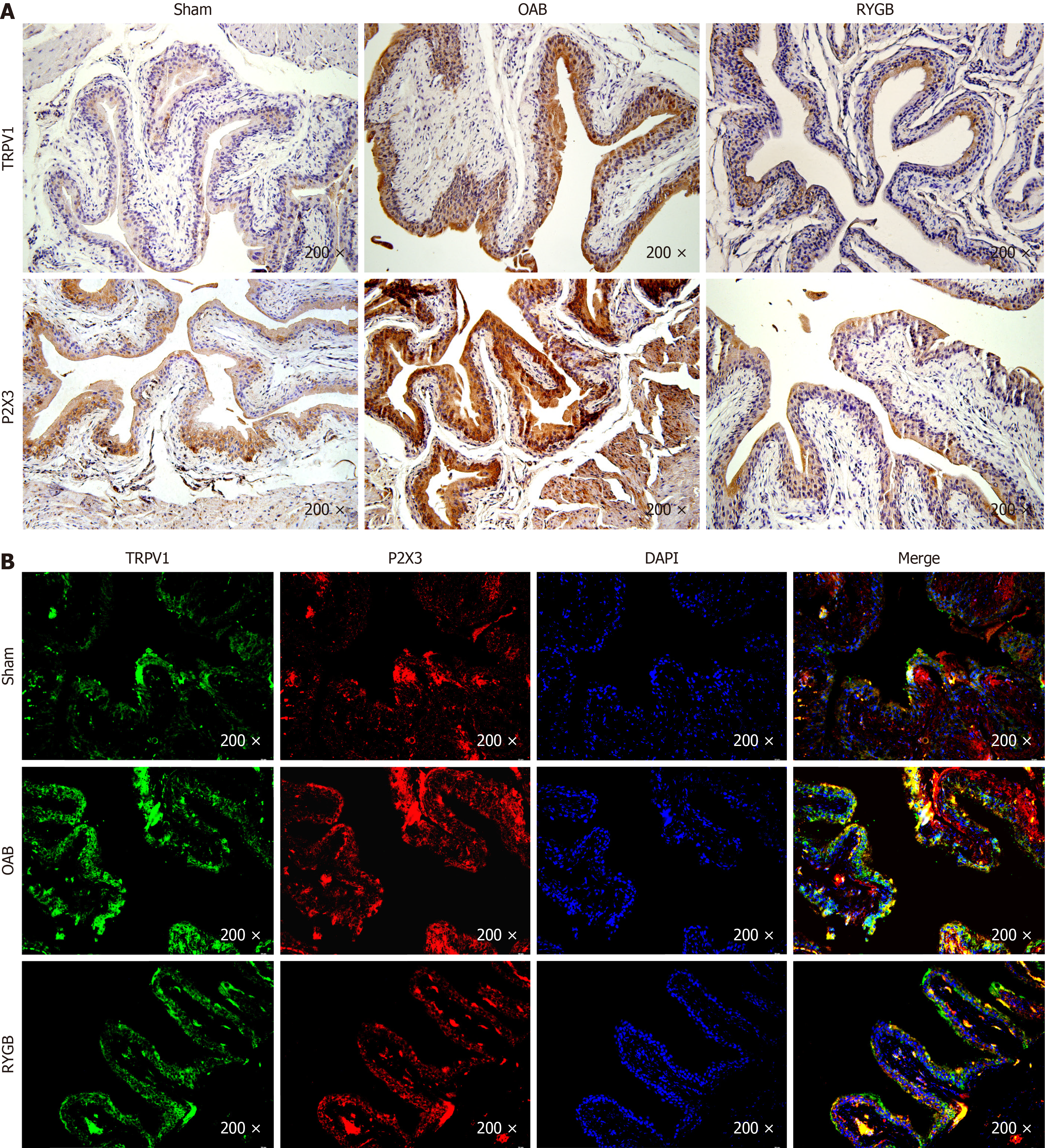

Immunohistochemical results showed that both TRPV1 and P2X3 were expressed in the epithelial layer of the bladder (Figure 5A). The TRPV1 and P2X3 positive staining depths of mice in the OAB group were significantly higher than those of mice in the control group. The TRPV1 and P2X3 positive staining depths of mice in the RYGB group were significantly lower than those of mice in the OAB group. Immunofluorescence costaining results (Figure 5B) showed that TRPV1 and P2X3 expressed in the bladder epithelium shared a positive region, and the costained regions in the RYGB group were lower in intensity and area than those in the OAB group.

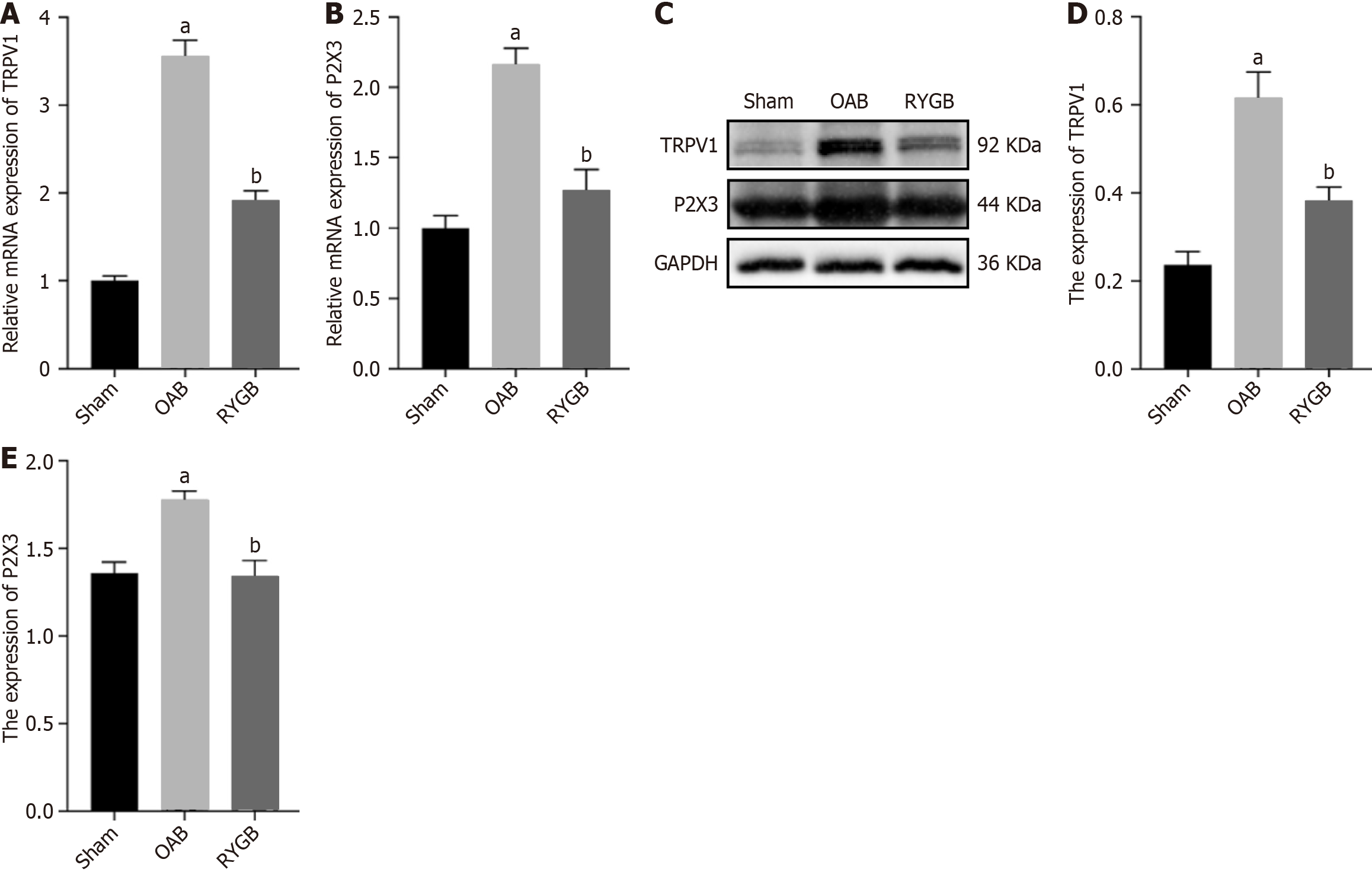

To further determine the expression levels of TRPV1 and P2X3 in the bladder of different groups, we tested the gene and protein differences of TRPV1 and P2X3 in bladder tissue. RT-PCR results showed significantly increased mRNA expression of TRPV1 and P2X3 in the OAB group and significantly decreased mRNA expression of TRPV1 and P2X3 in the RYGB group, as determined by relative quantification of mRNA (Figure 6A and B). In addition, western blot results showed that the protein levels of TRPV1 and P2X3 in the RYGB group were significantly lower than those in the OAB group (Figure 6C-E).

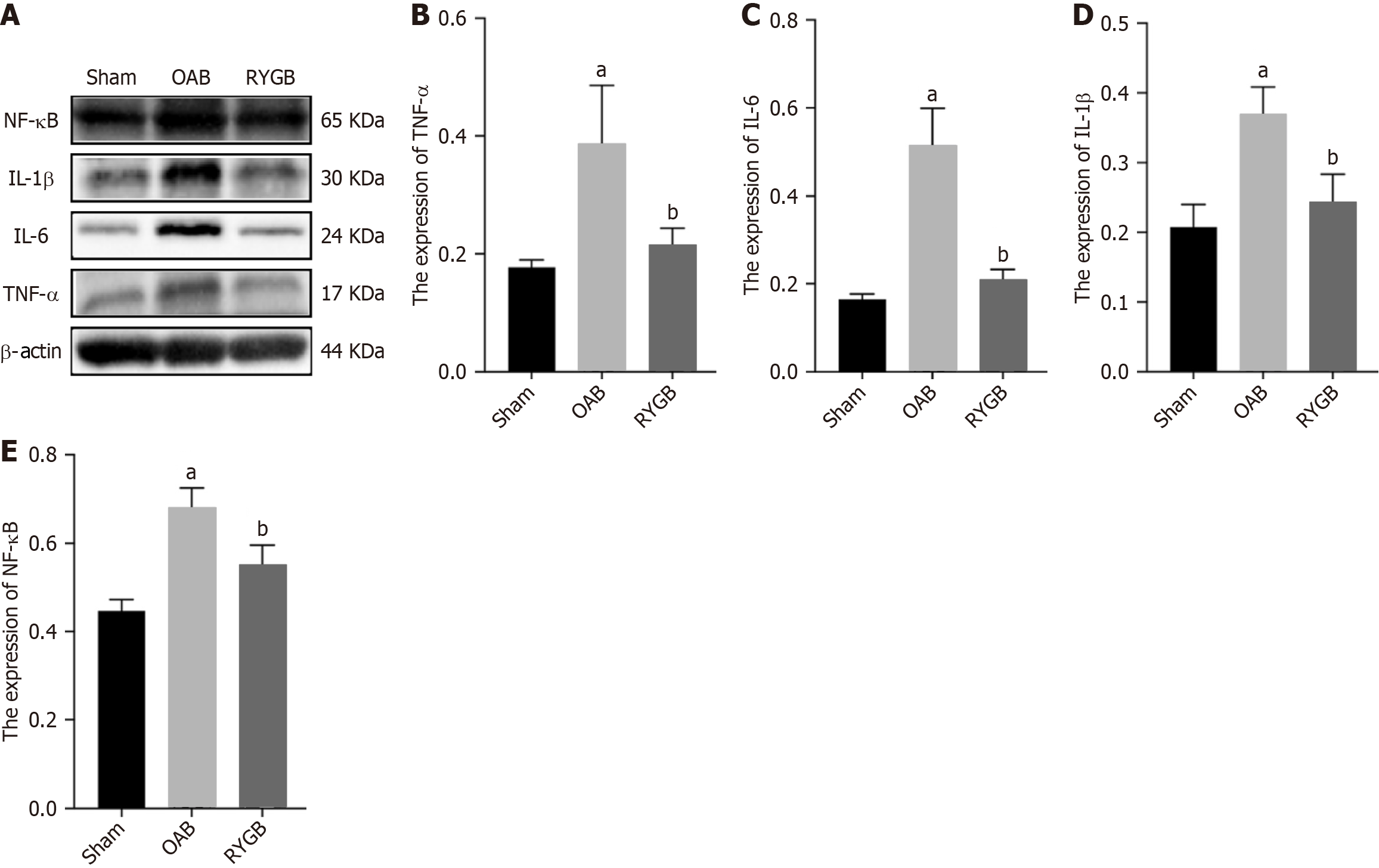

The level of inflammatory factors in bladder tissue of mice was detected by western blot, and the effect of RYGB treatment on the inflammatory state of the body was discussed. The results showed that the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and NF-κB in OAB mice increased significantly (Figure 7). Compared with OAB mice, the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and NF-κB in RYGB treated mice were significantly decreased (Figure 7).

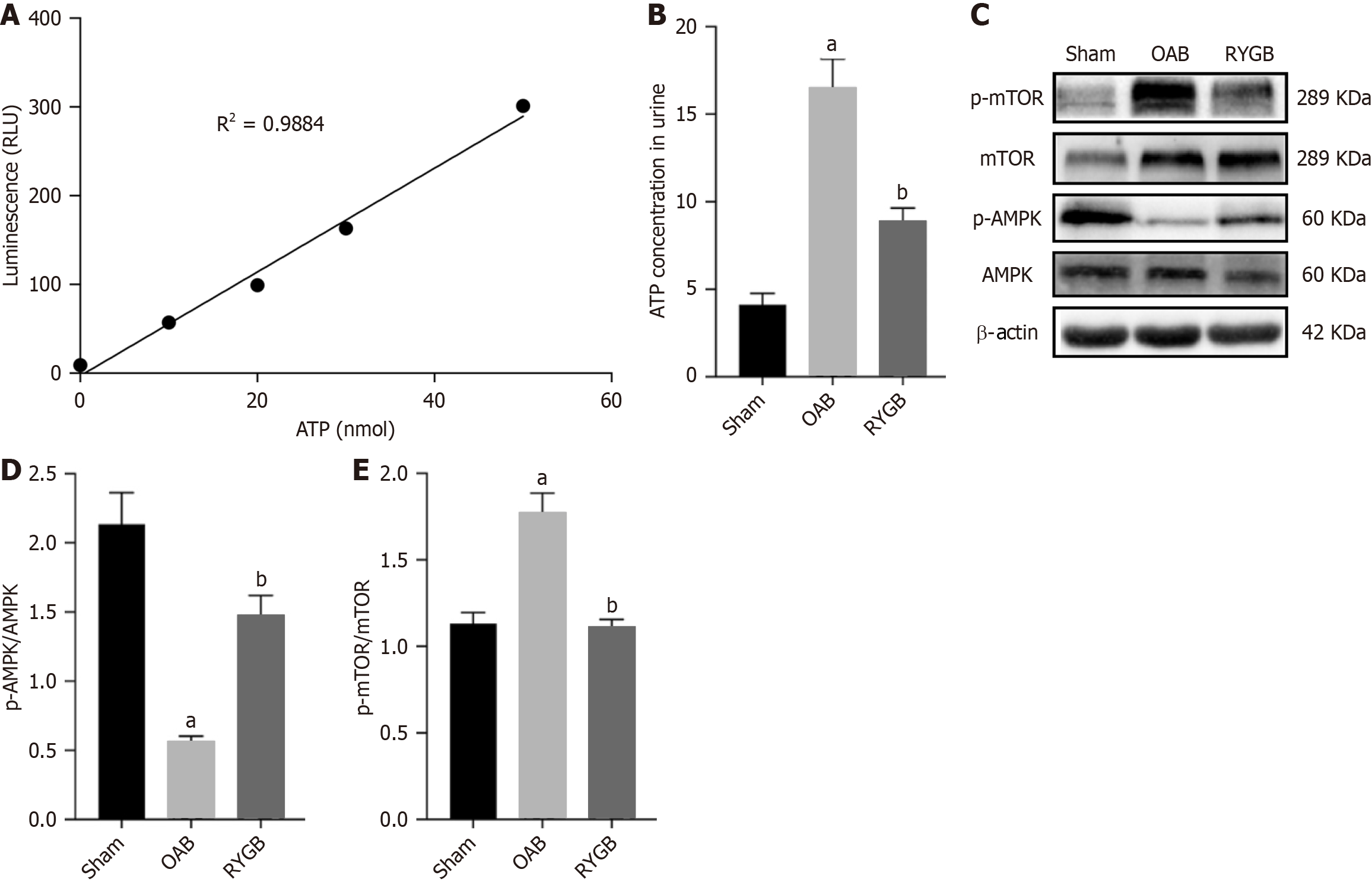

ATP is a key factor in the activation of P2X3, so we measured the level of ATP in the urine to reflect the activation of P2X3. Analysis of ATP levels in the urine of mice showed that OAB mice significantly increased ATP levels in the urine, but RYGB significantly decreased urine ATP content (Figure 8A and B). In addition, we also detected changes in the energy signaling pathway in the bladder tissue, and the OAB group showed decreased p-AMPK expression and increased p-mTOR expression. P-AMPK expression was increased while p-mTOR expression was decreased in the RYGB group (Figure 8C-E).

T2DM is an extremely prevalent form of diabetes that accounts for 90% of diagnosed cases and is associated with insulin resistance and chronic hyperglycemia[27]. Many clinical studies reported a broad spectrum of LUT symptoms in 90%-95% of patients with DM[28]. In addition, epidemiological study has shown that DM is an independent risk factor for OAB[29].The management of T2DM and its associated LUT symptoms is increasingly placing a financial strain on both individual patients and the healthcare system. Consequently, the search for a lasting cure has gained urgency[30]. Metabolic surgery provides superior glucose control and remission of T2DM compared with medical management alone[31].

RYGB had beneficial effects on weight loss and glucose metabolism. Rats that were treated with RYGB maintained a steady low level of weight, lower post\operative AUCGTT values, and lower AUCITT values[32]. This is consistent with our results. The mice lost much weight, and the blood glucose level and insulin sensitivity were remarkably improved 30 days after RYGB. It implies that RYGB improved hepatic insulin action (at least in the fasting state) or a change in the ability of factors other than insulin to regulate glucose production[33].

OAB is an early compensatory stage manifestation of diabetic bladder dysfunction, which mainly manifests as frequent micturition, enhanced bladder contractility, and increased bladder sensory sensitivity[34]. Our urine spot test and urodynamic findings showed that T2DM mice also exhibited the same OAB characteristics induced by an HFD, but the OAB symptoms of the mice were significantly relieved after RYGB surgical treatment. We suspect that the recovery of bladder function is related to the improvement of glucose metabolism in mice by RYGB because RYGB can improve the hyperglycemic environment and reduce the burden on bladder.

In streptozotocin diabetic rats 9 weeks after onset, scanning electron microscopy showed defective urothelial cells present in the bladders compared with controls, indicating a significant breach of the urothelial barrier[6]. Our results showed that after RYGB treatment, the bladder epithelial structure of T2DM mice recovered significantly, especially the umbrella cell layer and lamina propria. Overall, these findings suggest a potential unintended benefit of RYGB, likely due to weight loss or reducing hyperglycemia, and the specific reasons need further research and exploration.

P2X3 is not only involved in the regulation of afferent activities of the LUT but also has a positive effect on the occurrence of OAB[35]. TRPV1 plays an important role in OAB[36]. It has been demonstrated that diabetes increases the functional expression of bladder TRPV1[37]. Our results do support the notion that TRPV1 and P2X3 not only have increased expression in bladder epithelial tissue but also have the same localization. Following RYGB surgery, the expression of TRPV1 and P2X3 in the bladder epithelium was reduced at both the gene and protein levels.

The specific reason may be related to the reduction of inflammatory response by RYGB. DM is well known to confer a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. Many studies point to this inflammatory state as an underlying mechanism for the development of insulin resistance in obesity and T2DM[38]. Interestingly, bladder inflammation increased expression of TRPV1 channels in the membrane of urothelial cells[39]. Meanwhile, RYGB significantly decreases the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in peripheral monocytes isolated from patients with obesity and T2DM and contributes to hyperglycemia remission in T2DM rats[40]. By measuring the levels of inflammatory factors in the bladder tissue, we found that compared with the ham group, NF-κB, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α were significantly reduced in the RYGB group, indicating that RYGB significantly reduced the chronic inflammatory state caused by T2DM. Therefore, in the above experimental results and analysis, we believe that RYGB can alleviate the inflammatory state by reducing inflammatory factors, thereby reducing the expression of TRPV1 and P2X3.

Existing literature supports that ATP released from urothelial cells during bladder distention is a prime mediator to initiate the voiding reflex via the activation of P2X3 receptors on suburothelial sensory nerve fibers[41]. It has been confirmed that the effect of stretch is a major stimulus to release ATP. Acid-evoked ATP release was not pH-dependent and appeared to be mediated via both ASIC and TRPV1 receptors[42]. But capsaicin (receptor antagonist of TRPV1) can block the reaction to acid-evoked ATP release[42]. This means that TRPV1 may promote the activity of releasing ATP from UT. Therefore, TRPV1 may affect P2X3 activity by regulating ATP release.

Our results suggested that urine ATP content of mice treated with RYGB was significantly reduced compared with mice in the OAB group, indicating that RYGB might reduce ATP synthesis in bladder epithelium. To further verify our hypothesis and rule out the interference of urine ATP content reduction caused by the reduction of TRPV1 released by bladder epithelium due to RYGB, we detected the energy signaling pathway (AMPK) related to changes in ATP synthesis.

As an important physiological energy sensor, AMPK is the main regulator of cell energy homeostasis, which coordinates multiple metabolic pathways to balance energy supply[43]. ATP, as an important energy signaling molecule in the body, is naturally closely related to AMPK. AMPK activity is regulated by relative levels of ATP and AMP, both of which competitively bind to their γ subunits[44], by activating AMPK when ATP levels and ATP/AMP levels are decreased. It has been reported in the literature that p-AMPK, a direct downstream target of AMPK in the glomeruli of DM rats, is significantly reduced, and RYGB surgery showed a strong inhibition on these changes, leading to the restoration of AMPK activity to the normal level[45].

Our results were consistent with that of reduced p-AMPK expression in the OAB group compared with the sham group. However, after RYGB surgical treatment, the p-AMPK expression level of the mice was increased compared with the OAB group. Therefore, we believe that AMPK of OAB mice caused by T2DM is in an inhibitory state, which indirectly reflects the increase of ATP synthesis in bladder tissue. After the treatment with RYGB surgery, ATP synthesis in bladder is decreased, and AMPK is reactivated. Based on the above results, we suspect that RYGB surgery may have a role in balancing energy metabolism and thus inhibits the synthesis of excessive ATP in the bladder of HFD-induced T2DM mice. When the synthesis of ATP in the bladder is reduced, the effect of P2X3 will be significantly inhibited, thereby reducing the impulse of the afferent nerve of the bladder and improving the OAB of T2DM mice.

In addition, AMPK is also a negative regulator of mTOR[46]. Therefore, the AMPK-mTOR pathway also has signal transduction effects that regulate cell metabolism, energy homeostasis, and cell growth[47]. It has been summarized in review articles that activation of mTOR promotes the regeneration of adult retinal ganglion cells after optic nerve injury, and the overactivation of mTOR in astrocytes also promotes the formation of glial scars[48]. Thus, activation of mTOR leads to beneficial or negative proliferation of the body. As mentioned above, the morphological compensatory changes of bladder in HFD-induced T2DM mice are mainly related to the proliferation of muscle and collagen fibers.

In our results, the expression of p-mTOR in the sham group increased, along with the increase in the content of collagen fibers and α-SMA in the bladder. Following surgical treatment with RYGB, there were significant decreases in p-mTOR levels as well as decreases in bladder collagen fibers and α-SMA. Therefore, RYGB surgery may inhibit the expression of downstream mTOR by activating AMPK, ameliorate the adverse proliferation of bladder tissue components in OAB stage due to T2DM, and restore the normal tissue morphology and function of the bladder.

RYGB may inhibit the expression of TRPV1 and P2X3 in bladder epithelium by reducing inflammatory factors and further affect the synthesis of ATP in bladder through the AMPK-mTOR signaling pathway, which together improve diabetic bladder dysfunction.

| 1. | Agochukwu-Mmonu N, Pop-Busui R, Wessells H, Sarma AV. Autonomic neuropathy and urologic complications in diabetes. Auton Neurosci. 2020;229:102736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xu D, Gao J, Wang X, Huang L, Wang K. Prevalence of overactive bladder and its impact on quality of life in 1025 patients with type 2 diabetes in mainland China. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31:1254-1258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | He Q, Wu L, Deng C, He J, Wen J, Wei C, You Z. Diabetes mellitus, systemic inflammation and overactive bladder. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1386639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wei B, Zhao Y, Lin P, Qiu W, Wang S, Gu C, Deng L, Deng T, Li S. The association between overactive bladder and systemic immunity-inflammation index: a cross-sectional study of NHANES 2005 to 2018. Sci Rep. 2024;14:12579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Andersson KE. Treatment-resistant detrusor overactivity--underlying pharmacology and potential mechanisms. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2006;8-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hanna-Mitchell AT, Ruiz GW, Daneshgari F, Liu G, Apodaca G, Birder LA. Impact of diabetes mellitus on bladder uroepithelial cells. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R84-R93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li M, Sun Y, Simard JM, Chai TC. Increased transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) signaling in idiopathic overactive bladder urothelial cells. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:606-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cho KJ, Koh JS, Choi JB, Park SH, Lee WS, Kim JC. Changes in transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 and transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 in patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction. Investig Clin Urol. 2022;63:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Keay SK, Birder LA, Chai TC. Evidence for bladder urothelial pathophysiology in functional bladder disorders. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:865463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Birder LA, Wolf-Johnston AS, Sun Y, Chai TC. Alteration in TRPV1 and Muscarinic (M3) receptor expression and function in idiopathic overactive bladder urothelial cells. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2013;207:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling in the urinary tract in health and disease. Purinergic Signal. 2014;10:103-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling in the lower urinary tract. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2013;207:40-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Andersson KE. Potential Future Pharmacological Treatment of Bladder Dysfunction. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;119 Suppl 3:75-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ford AP. In pursuit of P2X3 antagonists: novel therapeutics for chronic pain and afferent sensitization. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:3-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | North RA, Jarvis MF. P2X receptors as drug targets. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83:759-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gonzalez JM, Ouazzani S, Berdah S, Cauche N, Delattre C, Peetermans JA, Santoro-Schulte A, Gjata O, Barthet M. Feasibility of a new bariatric fully endoscopic duodenal-jejunal bypass: a pilot study in adult obese pigs. Sci Rep. 2022;12:20275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Affinati AH, Esfandiari NH, Oral EA, Kraftson AT. Bariatric Surgery in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19:156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Peck BCE, Seeley RJ. How does 'metabolic surgery' work its magic? New evidence for gut microbiota. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2018;25:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Courcoulas AP, Gallagher JW, Neiberg RH, Eagleton EB, DeLany JP, Lang W, Punchai S, Gourash W, Jakicic JM. Bariatric Surgery vs Lifestyle Intervention for Diabetes Treatment: 5-Year Outcomes From a Randomized Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:866-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ikramuddin S, Korner J, Lee WJ, Thomas AJ, Connett JE, Bantle JP, Leslie DB, Wang Q, Inabnet WB 3rd, Jeffery RW, Chong K, Chuang LM, Jensen MD, Vella A, Ahmed L, Belani K, Billington CJ. Lifestyle Intervention and Medical Management With vs Without Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and Control of Hemoglobin A1c, LDL Cholesterol, and Systolic Blood Pressure at 5 Years in the Diabetes Surgery Study. JAMA. 2018;319:266-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bal BS, Finelli FC, Shope TR, Koch TR. Nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:544-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pareek M, Schauer PR, Kaplan LM, Leiter LA, Rubino F, Bhatt DL. Metabolic Surgery: Weight Loss, Diabetes, and Beyond. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:670-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Argyropoulos G. Bariatric surgery: prevalence, predictors, and mechanisms of diabetes remission. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Buchwald H, Buchwald JN. Metabolic (Bariatric and Nonbariatric) Surgery for Type 2 Diabetes: A Personal Perspective Review. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:331-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | He R, Yin Y, Li Y, Li Z, Zhao J, Zhang W. Esophagus-duodenum Gastric Bypass Surgery Improves Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Mice. EBioMedicine. 2018;28:241-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lai H, Yan Q, Cao H, Chen P, Xu Y, Jiang W, Wu Q, Huang P, Tan B. Effect of SQW on the bladder function of mice lacking TRPV1. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ferreira PEB, Beraldi EJ, Borges SC, Natali MRM, Buttow NC. Resveratrol promotes neuroprotection and attenuates oxidative and nitrosative stress in the small intestine in diabetic rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;105:724-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wang J, Lian DW, Yang XF, Xu YF, Chen FJ, Lin WJ, Wang R, Tang LY, Ren WK, Fu LJ, Huang P, Cao HY. Suo Quan Wan Protects Mouse From Early Diabetic Bladder Dysfunction by Mediating Motor Protein Myosin Va and Transporter Protein SLC17A9. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang CC, Jiang YH, Kuo HC. The Pharmacological Mechanism of Diabetes Mellitus-Associated Overactive Bladder and Its Treatment with Botulinum Toxin A. Toxins (Basel). 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Scott JD, O'Connor SC. Diabetes Risk Reduction and Metabolic Surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2021;101:255-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Nanni G, Castagneto M, Bornstein S, Rubino F. Bariatric-metabolic surgery versus conventional medical treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: 5 year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:964-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 852] [Cited by in RCA: 887] [Article Influence: 88.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang C, Zhang H, Liu H, Zhang H, Bao Y, Di J, Hu C. The genus Sutterella is a potential contributor to glucose metabolism improvement after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in T2D. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shah M, Laurenti MC, Dalla Man C, Ma J, Cobelli C, Rizza RA, Vella A. Contribution of endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 to changes in glucose metabolism and islet function in people with type 2 diabetes four weeks after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). Metabolism. 2019;93:10-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Klee NS, Moreland RS, Kendig DM. Detrusor contractility to parasympathetic mediators is differentially altered in the compensated and decompensated states of diabetic bladder dysfunction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019;317:F388-F398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ford AP, Undem BJ, Birder LA, Grundy D, Pijacka W, Paton JF. P2X3 receptors and sensitization of autonomic reflexes. Auton Neurosci. 2015;191:16-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bevan S, Quallo T, Andersson DA. TRPV1. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;222:207-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sharopov BR, Gulak KL, Philyppov IB, Sotkis AV, Shuba YM. TRPV1 alterations in urinary bladder dysfunction in a rat model of STZ-induced diabetes. Life Sci. 2018;193:207-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ying W, Fu W, Lee YS, Olefsky JM. The role of macrophages in obesity-associated islet inflammation and β-cell abnormalities. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:81-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 52.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Coelho A, Wolf-Johnston AS, Shinde S, Cruz CD, Cruz F, Avelino A, Birder LA. Urinary bladder inflammation induces changes in urothelial nerve growth factor and TRPV1 channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:1691-1699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Li M, Zhao Y, Zhang B, Wang X, Zhao T, Zhao T, Ren W. Hyperglycemia remission after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Implicated to altered monocyte inflammatory response in type 2 diabetes rats. Peptides. 2022;158:170895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Timóteo MA, Carneiro I, Silva I, Noronha-Matos JB, Ferreirinha F, Silva-Ramos M, Correia-de-Sá P. ATP released via pannexin-1 hemichannels mediates bladder overactivity triggered by urothelial P2Y6 receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;87:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sadananda P, Kao FC, Liu L, Mansfield KJ, Burcher E. Acid and stretch, but not capsaicin, are effective stimuli for ATP release in the porcine bladder mucosa: Are ASIC and TRPV1 receptors involved? Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;683:252-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Allain EP, Rouleau M, Vanura K, Tremblay S, Vaillancourt J, Bat V, Caron P, Villeneuve L, Labriet A, Turcotte V, Le T, Shehata M, Schnabl S, Demirtas D, Hubmann R, Joly-Beauparlant C, Droit A, Jäger U, Staber PB, Lévesque E, Guillemette C. UGT2B17 modifies drug response in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Cancer. 2020;123:240-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ke R, Xu Q, Li C, Luo L, Huang D. Mechanisms of AMPK in the maintenance of ATP balance during energy metabolism. Cell Biol Int. 2018;42:384-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 40.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wei X, Lu Z, Li L, Zhang H, Sun F, Ma H, Wang L, Hu Y, Yan Z, Zheng H, Yang G, Liu D, Tepel M, Gao P, Zhu Z. Reducing NADPH Synthesis Counteracts Diabetic Nephropathy through Restoration of AMPK Activity in Type 1 Diabetic Rats. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Cao L, Yin G, Du J, Jia R, Gao J, Shao N, Li Q, Zhu H, Zheng Y, Nie Z, Ding W, Xu G. Salvianolic Acid B Regulates Oxidative Stress, Autophagy and Apoptosis against Cyclophosphamide-Induced Hepatic Injury in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Animals (Basel). 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Schuster S, Penke M, Gorski T, Gebhardt R, Weiss TS, Kiess W, Garten A. FK866-induced NAMPT inhibition activates AMPK and downregulates mTOR signaling in hepatocarcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;458:334-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Huang S. mTOR Signaling in Metabolism and Cancer. Cells. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |