Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.104088

Revised: January 2, 2025

Accepted: February 7, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 81 Days and 2.8 Hours

Sepsis is a severe complication in hospitalized patients with diabetic foot (DF), often associated with high morbidity and mortality. Despite its clinical sig

To identify key risk factors and evaluate the predictive value of a nomogram model for sepsis in this population.

This retrospective study included 216 patients with DF admitted from January 2022 to June 2024. Patients were classified into sepsis (n = 31) and non-sepsis (n = 185) groups. Baseline characteristics, clinical parameters, and laboratory data were analyzed. Independent risk factors were identified through multivariable logistic regression, and a nomogram model was developed and validated. The model's performance was assessed by its discrimination (AUC), calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow test, calibration plots), and clinical utility [decision curve analysis (DCA)].

The multivariable analysis identified six independent predictors of sepsis: Dia

The nomogram prediction model, based on six key risk factors, demonstrates strong predictive value, calibration, and clinical utility for sepsis in patients with DF. This tool offers a practical approach for early risk stratification, enabling timely interventions and improved clinical management in this high-risk population.

Core Tip: Sepsis remains a significant complication in diabetic foot (DF) patients, often associated with poor outcomes and high mortality. However, early identification of at-risk individuals remains a clinical challenge. In our study, we identified six independent risk factors-diabetes duration, DF Texas grade, white blood cell count, glycated hemoglobin, C-reactive protein, and albumin-that contribute significantly to the risk of sepsis. We developed a nomogram incorporating these factors, demonstrating excellent diagnostic performance and clinical utility.

- Citation: Han WW, Fang JJ. Analysis of risk factors and predictive value of a nomogram model for sepsis in patients with diabetic foot. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(4): 104088

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i4/104088.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.104088

Diabetic foot (DF) is a significant consequence of diabetic mellitus, marked by infection, ulceration, and/or deep tissue loss linked to neurological impairments and various levels of peripheral vascular disease (PVD). It presents a considerable global public health concern due to its elevated morbidity and mortality rates, together with its huge economic burden on healthcare systems[1,2]. Sepsis, a life-threatening organ failure resulting from a dysregulated host response to infection, is a significant consequence of DF. Individuals with DF face heightened susceptibility to sepsis owing to chronic infections, protracted wound healing, and compromised immune responses, highlighting the necessity for prompt detection and efficient management approaches[3,4].

Sepsis in DF patients is a multifactorial condition driven by risk factors such as age, comorbidities, glycemic control, and infection severity. Early detection of sepsis risk is essential to prevent progression from localized infection to systemic organ failure. However, due to the complex nature of sepsis in this population, current tools often lack the necessary sensitivity and specificity. This underscores the need for predictive models that can assist clinicians in early diagnosis and targeted interventions, ultimately improving patient outcomes. The nomogram, a graphical depiction of a statistical model, has become an essential instrument in clinical research for forecasting personalized risks and outcomes[5-7]. Nomograms integrate several characteristics into a singular prediction model, offering an intuitive and accurate risk estimation that assists doctors in early diagnosis and tailored treatment planning. In recent years, nomograms have been extensively utilized in multiple medical disciplines, including oncology, cardiology, and infectious diseases, due to their capacity to improve prognostic precision and guide evidence-based therapies. Nonetheless, their utilization in sepsis prediction among DF patients is constrained, underscoring a deficiency in existing studies[8-10]. Existing models for DF complications focus on local factors but overlook systemic markers crucial for early sepsis detection. Tools like the Wagner Classification and Pedal Arterial Disease Score lack sensitivity and specificity for predicting sepsis, highlighting the need for more comprehensive models to guide timely intervention.

We hypothesize that specific clinical and laboratory parameters are significantly associated with the development of sepsis in patients with DF, and that a nomogram model incorporating these factors can accurately predict the risk of sepsis in this high-risk population. This study intends to thoroughly examine the risk factors linked to sepsis in patients with DF and to assess the predictive efficacy of a nomogram model specifically designed for this high-risk group. This study aims to identify and validate essential clinical and laboratory indicators to develop a reliable predictive tool that aids healthcare providers in the early detection of sepsis and enhances therapy options.

This retrospective study, performed at our institution from January 2022 to June 2024, examined risk factors and assessed the predictive efficacy of a nomogram model for sepsis in patients with DF. Patients were included if they had a confirmed diagnosis of DF, defined by the International Working Group on the DF guidelines, with evidence of infection, ulceration, or tissue destruction associated with diabetic neuropathy and/or PVD. Complete medical records, including clinical, laboratory, and imaging data, were required, and all participants provided written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included non-DF conditions (e.g., traumatic ulcers), terminal illnesses (e.g., advanced malignancy), severe systemic diseases, immunocompromised states (e.g., HIV/AIDS, immunosuppressive therapy), or recent major surgery or trauma. A total of 216 patients were enrolled, consisting of 31 in the sepsis group and 185 in the non-sepsis group. The research complied with the STROBE requirements[11] and received approval from the hospital's Ethics Committee.

Demographic and baseline characteristics: Key information included age, gender, medical history, smoking and alcohol drinking history, and family history of pertinent diseases. These baseline characteristics were collected to investigate potential predisposing factors and demographic impacts.

Clinical parameters: The clinical data included the duration of diabetes mellitus and the Texas categorization of DF severity. These measures provide insights about the disease's course and the degree of foot involvement.

Laboratory data were collected within 24 hours of patient arrival to ascertain baseline biochemical and hematological status. Included key indices: (1) Hematological markers: White blood cell count (WBC), neutrophil count (NEU), lymphocyte count (LYM), and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR); (2) Red blood cell parameters: Hemoglobin and red cell distribution width; (3) Platelet and protein levels: Platelet count and albumin (Alb); (4) Glycemic and inflammatory markers: Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and C-reactive protein (CRP); and (5) Renal and liver function indicators: Total bilirubin, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and serum creatinine.

The severity of DF lesions was assessed using the Texas Grading System. This classification system stratifies lesions by grade and stage: Grade 0: History of foot ulcer without active ulceration. Grade 1: Superficial ulcer. Grade 2: Ulcer extending to tendons. Grade 3: Ulcer involving bone or joint structures. Stages: Stage A: No infection or ischemia. Stage B: Presence of infection. Stage C: Presence of ischemia. Stage D: Coexistence of infection and ischemia.

Peripheral neuropathy: Peripheral neuropathy was assessed through clinical symptoms and physical examination results. When required, nerve conduction studies and additional neurophysiological evaluations were conducted to validate the diagnosis.

PVD: PVD was diagnosed through clinical signs and imaging investigations. Diagnostic modalities including Doppler ultrasonography, computed tomography angiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and digital subtraction an

Diabetic retinopathy: Diabetic retinopathy (DR) was evaluated with dilated fundoscopic examination. The existence of microaneurysms or more pronounced retinal alterations was deemed diagnostic of DR.

Diabetic nephropathy: Diabetic nephropathy (DN) was diagnosed based on an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/min/1.73 m² or a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio greater than 30 mg/g for a duration beyond three months.

The main endpoint of this study was the incidence of sepsis during hospitalization. Sepsis was diagnosed according to the sepsis-3 criteria, which characterize sepsis as a life-threatening organ failure resulting from a dysregulated host response to infection. Organ dysfunction was assessed with the sequential organ failure assessment score, where an increase of ≥ 2 points signifies substantial organ failure. Clinical and laboratory signs, including fever or hypothermia, tachycardia, hypotension, altered mental status, leukocytosis or leukopenia, and high levels of CRP and procalcitonin, were utilized to substantiate the diagnosis.

Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing SPSS version 27.0 and R version 4.3.1. Continuous variables adhering to a normal distribution were represented as mean ± SD and analyzed using independent sample t-tests to evaluate inter-group differences. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, with relationships examined using χ² testing; where the assumptions for the χ² test were not satisfied, Fisher's exact test was utilized. An analysis of multicollinearity was conducted to exclude predictors exhibiting direct correlations, hence confirming the reliability of the results. Multivariable logistic regression was utilized to ascertain risk variables for sepsis in patients with DF, and a nomogram model was developed based on the identified factors. The model's performance was evaluated based on discrimination, utilizing the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC); calibration, assessed via the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and calibration plots; and clinical utility, analyzed through decision curve analysis (DCA). The model underwent internal validation through the bootstrap resampling technique. Statistical significance was assessed using two-tailed tests, with a P value of less than 0.05 deemed significant for all analyses.

The study comprised 216 patients with DF, with a mean age of 63.50 ± 11.40 years. The cohort was predominantly male, constituting 69.44% of the participants, whilst females comprised 30.56%. Comorbidities were common in the study population, with 62.96% exhibiting hypertension, 48.61% indicating coronary heart disease, and 31.94% having a history of cerebrovascular disease. Furthermore, peripheral neuropathy and PVD were prevalent, noted in 98.61% and 97.69% of patients, respectively. Diabetic complications comprised DR in 25.93% of individuals and DN in 20.83%. 39.35% of patients reported smoking, while 30.56% reported alcohol intake. Additionally, 53.70% of the group indicated a familial history of diabetes-related ailments. Concerning the length of diabetes, 80.09% of patients experienced a disease course of 10 years or more, underscoring the chronic nature of the ailment in this demographic. The severity of DF was evaluated utilizing the Texas grading system, revealing that 70.37% of patients were categorized as Grade 3 Stage D, signifying advanced disease (Table 1).

| Factors | β value | Standard error value | Wald value | OR value | 95%CI for OR | P value |

| Diabetes duration | 1.052 | 0.501 | 4.302 | 2.714 | 1.053-7.308 | 0.039 |

| Diabetic foot Texas grade | 0.828 | 0.401 | 4.129 | 2.314 | 1.014-5.273 | 0.046 |

| WBC | 0.153 | 0.057 | 7.675 | 1.133 | 1.042-1.291 | 0.007 |

| Alb | -0.120 | 0.049 | 6.481 | 0.851 | 0.805-0.972 | 0.011 |

| HbA1c | 0.412 | 0.089 | 22.975 | 1.536 | 1.278-1.784 | < 0.001 |

| CRP | 0.006 | 0.005 | 5.161 | 1.008 | 1.000-1.016 | 0.038 |

| Factors | β value | Standard error value | Wald value | OR value | 95%CI for OR | P value |

| Diabetes duration | 1.052 | 0.501 | 4.302 | 2.714 | 1.053-7.308 | 0.039 |

| Diabetic foot Texas grade | 0.828 | 0.401 | 4.129 | 2.314 | 1.014-5.273 | 0.046 |

| WBC | 0.153 | 0.057 | 7.675 | 1.133 | 1.042-1.291 | 0.007 |

| Alb | -0.120 | 0.049 | 6.481 | 0.851 | 0.805-0.972 | 0.011 |

| HbA1c | 0.412 | 0.089 | 22.975 | 1.536 | 1.278-1.784 | < 0.001 |

| CRP | 0.006 | 0.005 | 5.161 | 1.008 | 1.000-1.016 | 0.038 |

The univariate analysis indicated multiple significant differences between the sepsis and non-sepsis groups in terms of clinical features and laboratory markers. Notably, individuals with sepsis demonstrated a substantially longer duration of diabetes (≥ 10 years: 93.55% vs 77.84%; P = 0.043) and more severe DF severity, as determined by the Texas grading system (Grade 3 Stage D: 87.10% vs 67.57%; P = 0.028). Among laboratory indicators, markers of inflammation and immune response exhibited the most significant disparities. The sepsis cohort exhibited elevated CRP levels [110.00 (77.50, 187.50) vs 25.00 (8.00, 64.00); P < 0.001], WBC counts [14.10 (11.00, 18.50) vs 8.10 (6.40, 10.80); P < 0.001], and NEU counts [10.90 (8.30, 15.50) vs 5.80 (4.10, 8.00); P < 0.001]. The NLR was markedly increased in the sepsis group [10.30 (5.80, 16.00) vs 3.80 (2.30, 6.30); P < 0.001], indicating an intensified inflammatory condition. Conversely, LYM levels were markedly reduced in the sepsis cohort [1.20 (0.80, 1.50) vs 1.50 (1.10, 2.00); P < 0.001] (Table 1).

Moreover, dietary and renal function metrics exhibited substantial differences across the groups. Serum Alb concentrations were significantly reduced in the sepsis cohort (29.70 ± 3.90 g/L vs 35.70 ± 4.70 g/L; P < 0.001), reflecting inferior nutritional status. BUN values were significantly increased in the sepsis group [8.10 (5.70, 11.20) vs 6.80 (5.10, 8.70); P < 0.001], indicating compromised renal function. Glycemic control, measured by HbA1c, was inferior in the sepsis group [11.20 (9.00, 12.20) vs 8.30 (7.00, 9.90); P < 0.001]. Other parameters, such as age, gender, comorbidities (hypertension, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease), and lifestyle factors (smoking and alcohol intake), exhibited no significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1). In conclusion, severe DF conditions, extended duration of diabetes, heightened inflammatory markers, suboptimal nutritional status, and compromised glycemic and renal functions were strongly correlated with the onset of sepsis in patients with DF.

Multivariate logistic regression study showed numerous independent risk factors related with the development of sepsis in individuals with DF. Among these, diabetes duration and the severity of DF lesions, as judged by the Texas grading system, were significant predictors. Patients with a diabetic duration of ≥ 10 years had a greater risk of sepsis (OR = 2.714, 95%CI: 1.053-7.308, P = 0.039). Similarly, patients with advanced DF severity (Grade 3 Stage D) demonstrated a higher chance of sepsis (OR = 2.314, 95%CI: 1.014-5.273, P = 0.046). Laboratory indications also underlined the connection between systemic inflammation and sepsis. Elevated WBC levels were a strong predictor of sepsis (OR = 1.133, 95%CI: 1.042-1.291, P = 0.007), as were higher HbA1c levels (OR = 1.536, 95%CI: 1.278-1.784, P < 0.001) and CRP levels (OR = 1.008, 95%CI: 1.000-1.016, P = 0.038). These findings underline the significance of both glycemic imbalance and inflammatory load in the etiology of sepsis in this population. Conversely, nutritional status, as measured by serum Alb levels, was inversely linked with sepsis risk. Lower Alb levels significantly increased the incidence of sepsis (OR = 0.851, 95%CI: 0.805-0.972, P = 0.011), suggesting that low nutritional reserves may predispose individuals to systemic infections (Table 2). In conclusion, prolonged diabetes duration, advanced DF severity, raised inflammatory markers (WBC, CRP), poor glycemic control (HbA1c), and low serum Alb levels were independently related with an increased risk of sepsis in DF patients.

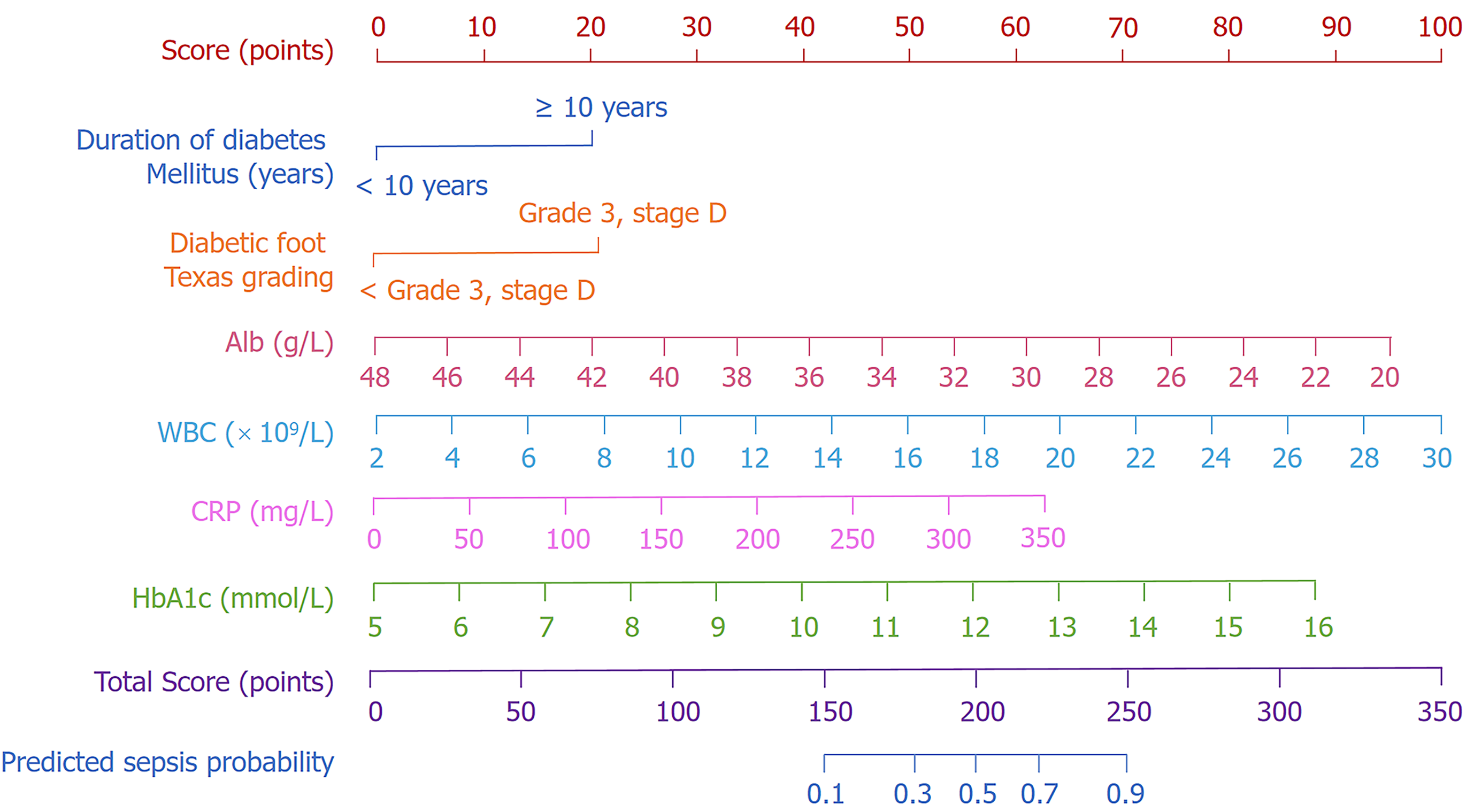

A nomogram prediction model was created to estimate the likelihood of sepsis in hospitalized patients with DF, utilizing six independent risk factors identified through multivariate logistic regression analysis. These factors comprised duration of diabetes, DF Texas grade, WBC, HbA1c, CRP, and serum Alb levels. Each variable was assigned a specific score reflecting its contribution to sepsis risk. The cumulative scores of all variables were aggregated to derive a total score, which was subsequently correlated to a probability of sepsis using the scale at the bottom of the nomogram (Figure 1). The model demonstrates that elevated total scores correlate with an increased risk of sepsis, serving as a quantitative instrument for personalized risk assessment.

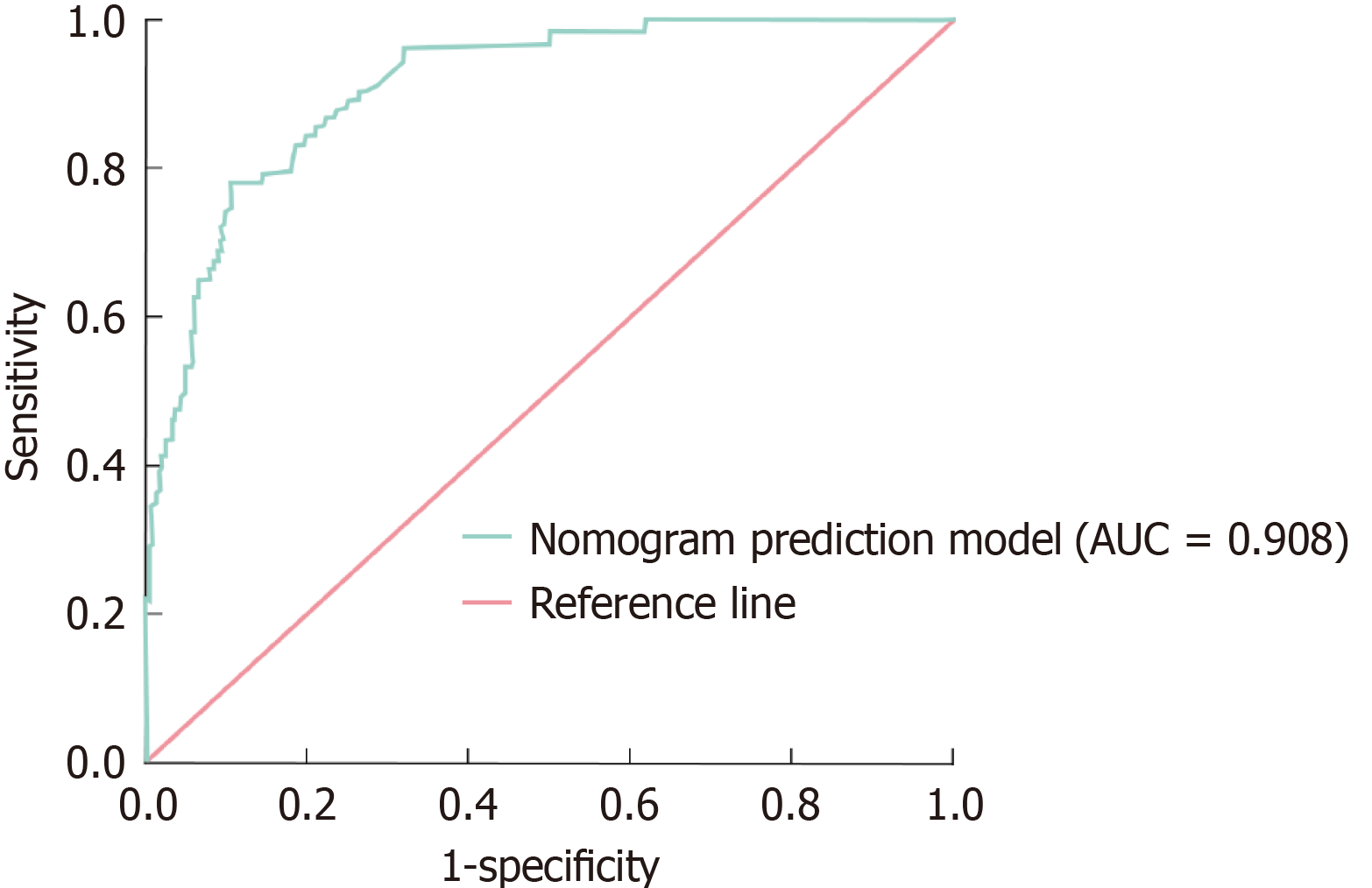

The diagnostic efficacy of the nomogram prediction model for sepsis in hospitalized patients with DF was assessed using the AUC. The model exhibited remarkable diagnostic efficacy, with an AUC of 0.908 (95%CI: 0.865-0.956). At the optimal threshold established by the maximal Youden score, the model attained a sensitivity of 85.8% and a specificity of 81.6%, underscoring its efficacy in differentiating between patients with and without sepsis (Figure 2). Bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations) was performed to guarantee the model's resilience and dependability. Following resampling, the model's AUC remained constant at 0.906 (95%CI: 0.863-0.952), demonstrating reliable predicted performance across diverse data samples. These results validate the model's significant diagnostic utility in clinical environments.

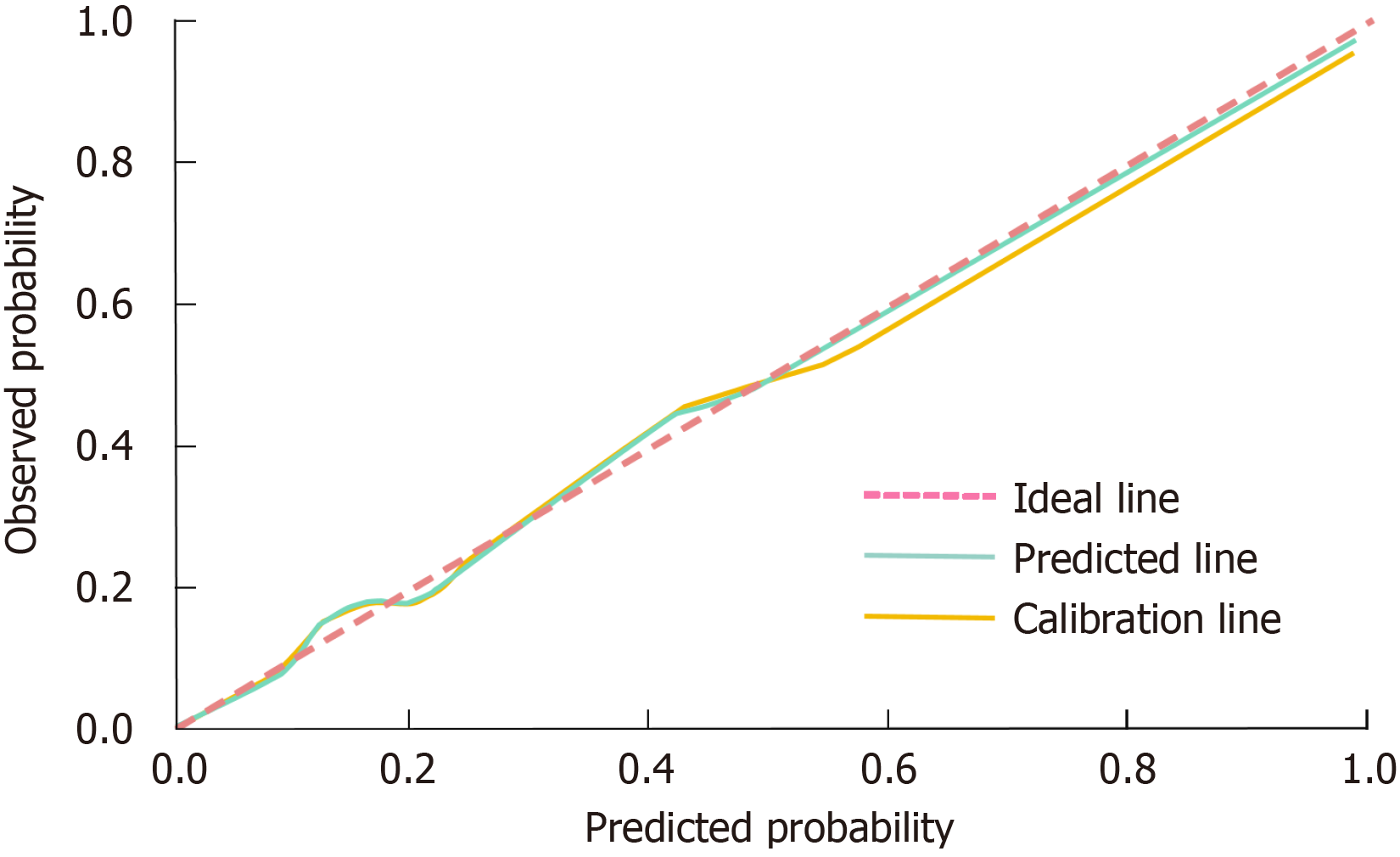

The calibration of the nomogram prediction model was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and calibration curves. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test produced a χ² value of 2.958 and a P value of 0.926, signifying no significant discrepancy between predicted and observed outcomes. This finding indicates that the model exhibits excellent calibration and is appropriate for clinical prediction. Furthermore, the calibration curve corroborated the model’s reliability, as the predicted probabilities closely matched the actual probabilities across the spectrum of risk scores, demonstrating strong concordance and consistency. The calibration curve's visual proximity to the reference line (indicative of perfect prediction) underscores the model's ability to provide accurate probability estimates for sepsis occurrence (Figure 3).

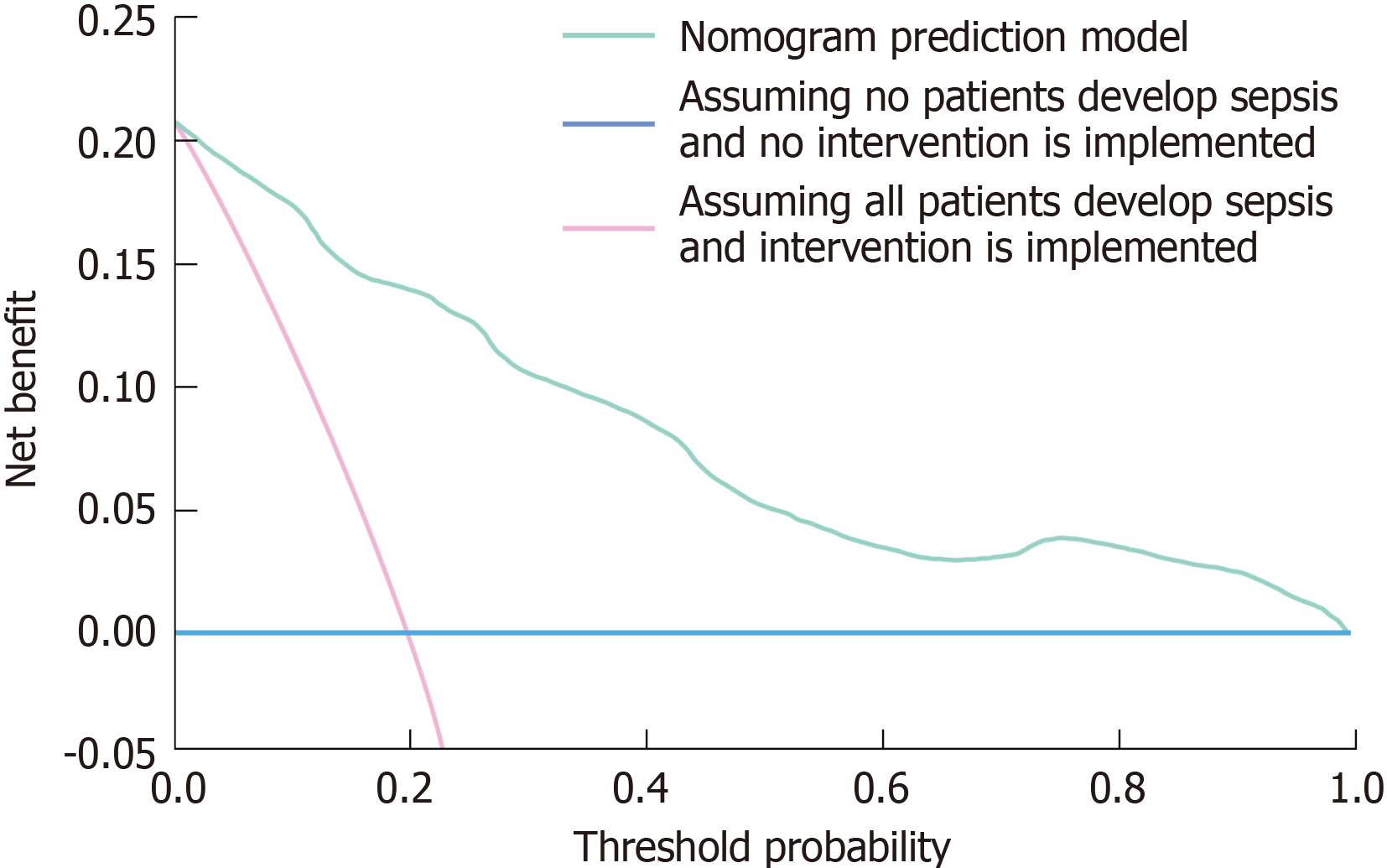

The clinical efficacy of the nomogram prediction model was evaluated utilizing DCA. The DCA curve visually illustrates the net benefit of the model at various threshold probabilities. The horizontal line in the analysis signifies the assumption that no patients contract sepsis, leading to the absence of interventions and a net benefit of zero. In contrast, the diagonal line presupposes that all patients acquire sepsis and undergo therapies, leading to a net adverse effect due to superfluous procedures in low-risk individuals. The nomogram prediction model exhibited a significantly greater net benefit than the two extreme scenarios across various threshold probabilities (Figure 4). This discovery underscores the model's capacity to precisely identify individuals at elevated risk of sepsis, so reducing wasteful treatments while facilitating prompt therapy for those truly at danger. The enhanced net benefit of the nomogram prediction model demonstrates its significant therapeutic usefulness. Integrating this technology into clinical practice enables healthcare practitioners to increase decision-making, optimize resource allocation, and improve outcomes for hospitalized patients with DF at risk of sepsis.

Sepsis, a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in DF patients, is influenced by factors such as peripheral neuropathy, vascular insufficiency, and immune dysfunction due to chronic hyperglycemia, with early risk prediction remaining a clinical challenge[12,13]. Matsinhe et al[14] explored the use of machine learning algorithms to predict mortality in diabetic foot sepsis patients during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in South Africa, while Wang et al[15] developed machine learning models to predict the risk of hard-to-heal diabetic foot ulcers in the Chinese population. Similarly, our study addresses the identification of sepsis risk factors in diabetic foot patients, but employs a traditional nomogram-based model. The nomogram provides a visual tool that allows clinicians to quickly assess patient risk by simply referencing a chart. Its structure is intuitive, requiring no advanced technical expertise to interpret, unlike machine learning models that typically require specialized data science knowledge. A key advantage of the nomogram is its interpretability, clearly demonstrating how each variable contributes to the overall risk prediction, enabling clinicians to understand the factors driving a patient's risk score. Additionally, the nomogram is not resource-intensive and can be implemented in hospitals without the need for complex computational infrastructure. This is especially important in resource-limited settings, where machine learning models may be impractical due to the requirement for high-performance computing and large datasets. While machine learning models often require extensive datasets for training and validation, the nomogram is based on a relatively small set of clinical variables, making it feasible for hospitals with limited data. It is also easy to update as new clinical data becomes available, offering flexibility for continuous improvement. While we acknowledge the successful application of machine learning methods in certain fields, our nomogram model remains a practical alternative, particularly for clinicians who lack expertise in machine learning, as well as interdisciplinary clinicians who may not possess sufficient clinical experience. Future research may explore combining these approaches to further enhance prediction accuracy.

The univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that prolonged diabetes duration and advanced DF severity (Grade 3 Stage D) were independently associated with an increased risk of sepsis. Chronic hyperglycemia in long-standing diabetes contributes to microvascular and macrovascular complications, which compromise immune function and wound healing, creating a favorable environment for severe infections. The Texas grading system's association with sepsis underscores the critical role of tissue destruction and infection severity in promoting systemic inflammation. Laboratory indicators highlighted the significant contribution of inflammatory and immune dysregulation to sepsis development. Elevated WBC, CRP, and NEU levels, along with a heightened NLR, reflect a systemic inflammatory response characteristic of sepsis. These markers are indicative of the host's attempt to combat infection; however, excessive and dysregulated inflammation can lead to organ dysfunction, a hallmark of sepsis. The lower LYM levels observed in the sepsis group suggest immune exhaustion or suppression, further exacerbating the risk of infection spread and systemic involvement. Additionally, poor nutritional and metabolic statuses were significant contributors to sepsis risk. Hypoalbuminemia was strongly associated with sepsis, reflecting not only malnutrition but also a hypercatabolic state driven by systemic inflammation. Elevated HbA1c levels in the sepsis group highlight the impact of poor glycemic control, which impairs immune responses, promotes bacterial growth, and delays tissue repair. These findings emphasize the need for comprehensive management of metabolic and nutritional factors in patients with DF.

Univariate and multivariate studies indicated that extended diabetes duration and severe DF (Grade 3 Stage D) were independently correlated with an elevated risk of sepsis. Persistent hyperglycemia in prolonged diabetes leads to microvascular and macrovascular problems, impairing immune function and wound healing, hence fostering conditions conducive to serious infections. The Texas grading system's correlation with sepsis highlights the essential influence of tissue damage and infection severity in exacerbating systemic inflammation. Laboratory markers emphasized the substantial role of inflammatory and immunological dysfunction in the progression of sepsis. Increased WBC, CRP, and NEU levels, coupled with an elevated NLR, indicate a systemic inflammatory response typical of sepsis. These signs signify the host's effort to counteract infection; nevertheless, severe and uncontrolled inflammation may result in organ malfunction, a characteristic of sepsis. The diminished LYM levels reported in the sepsis cohort indicate immunological exhaustion or inhibition, hence increasing the probability of infection dissemination and systemic involvement[16,17]. Moreover, inadequate dietary and metabolic conditions were substantial factors in the risk of sepsis. Hypoalbuminemia was significantly correlated with sepsis, indicating both malnutrition and a hypercatabolic condition induced by systemic inflammation. Increased HbA1c levels in the sepsis cohort underscore the effects of inadequate glycemic regulation, which hinders immunological responses, facilitates bacterial proliferation, and postpones tissue repair. These findings underscore the necessity for thorough control of metabolic and dietary variables in patients with DF[18,19].

This study's predictive nomogram model incorporates six independent risk factors: Length of diabetes, severity of DF, WBC, HbA1c, CRP, and Alb levels. The model offers a comprehensive tool for personalized risk evaluation by integrating clinical and laboratory characteristics. The elevated AUC values (0.919 prior to and 0.918 subsequent to Bootstrap resampling) indicate the model's superior diagnostic efficacy. Its capacity to attain elevated sensitivity and specificity highlights its promise for the early identification of high-risk individuals, facilitating prompt interventions. The model's calibration was verified using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and calibration curves, demonstrating a robust concordance between predicted and observed probabilities. This consistency guarantees the model's dependability across various clinical environments. DCA further illustrated the model's clinical utility by indicating a greater net benefit relative to extreme intervention scenarios, underscoring its significance in improving resource allocation and reducing unnecessary treatments[20,21].

A post hoc power analysis was conducted to assess the adequacy of the sample size in detecting significant predictors among the six identified risk factors: Diabetes duration, DF grading, WBC count, HbA1c, CRP, and serum Alb levels. With 216 patients (31 sepsis, 185 non-sepsis), the observed OR ranged from 0.851 to 2.714. The analysis indicated that the sample size provides sufficient power (85%) to detect moderate to large effect sizes (e.g., OR ≥ 1.5), exceeding the conventional threshold of 80%. Even for smaller effect sizes (e.g., CRP, OR = 1.008), the significant P value supports adequate power. Therefore, the sample size is deemed sufficient to reliably identify and validate the six risk factors for sepsis in DF patients. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify the final six independent risk factors, selected based on their statistical significance in univariate analyses and established relevance to sepsis pathophysiology. Non-significant variables, including age, gender, and comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, coronary heart disease), were excluded due to their lack of significant association with sepsis (P > 0.05). Including these variables could lead to overfitting and diminish the model’s predictive accuracy. By focusing on the most significant predictors-diabetes duration, DF severity, WBC, HbA1c, CRP, and Alb-the final nomogram enhances predictive reliability. This streamlined model offers improved clinical utility for early sepsis detection and targeted intervention, ultimately contributing to better patient outcomes.

However, limitations should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective design inherently carries the risk of selection bias, as patients who did not seek treatment or who presented with milder disease may not have been included. Additionally, reliance on clinical records introduces the possibility of misclassification bias, as not all relevant clinical data may have been consistently recorded across patients. Despite efforts to ensure completeness and accuracy, missing or incomplete data could still influence the study’s results. Second, while multivariable logistic regression and internal validation through bootstrap resampling were used to adjust for confounders and assess the model's robustness, the retrospective nature of the study means that unmeasured confounders, such as patients' adherence to treatment or socio-economic factors, may not have been accounted for. These factors could affect sepsis development and thus influence the model's predictive accuracy. Third, the study was conducted at a single center, which may limit the external generalizability of our findings. Our cohort predominantly consisted of patients from a specific geographic region and healthcare setting, and the model’s performance may vary in different clinical contexts or populations. Therefore, external validation with larger and more diverse populations is needed to confirm the model's applicability across different clinical settings.

The nomogram prediction model incorporating six key factors-diabetes duration, DF Texas grade, WBC, HbA1c, CRP, and Alb-could offer strong predictive value for sepsis in hospitalized patients with DF. This model might provide a reliable tool for early risk stratification, potentially enabling timely interventions and improved clinical management in this high-risk population. However, further prospective studies and external validation are needed to confirm its generalizability and clinical applicability.

We sincerely thank every patient who participated in this study.

| 1. | Armstrong DG, Tan TW, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Review. JAMA. 2023;330:62-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 245.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rehman ZU, Khan J, Noordin S. Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Contemporary Assessment And Management. J Pak Med Assoc. 2023;73:1480-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sun B, Chen Y, Man Y, Fu Y, Lin J, Chen Z. Clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and prognostic nutritional index on prediction of occurrence and development of diabetic foot-induced sepsis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1181880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Costantini E, Carlin M, Porta M, Brizzi MF. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and sepsis: state of the art, certainties and missing evidence. Acta Diabetol. 2021;58:1139-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dmitriyeva M, Kozhakhmetova Z, Urazova S, Kozhakhmetov S, Turebayev D, Toleubayev M. Inflammatory Biomarkers as Predictors of Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcer. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2022;18:e280921196867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Russell CD, Parajuli A, Gale HJ, Bulteel NS, Schuetz P, de Jager CPC, Loonen AJM, Merekoulias GI, Baillie JK. The utility of peripheral blood leucocyte ratios as biomarkers in infectious diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2019;78:339-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jalali A, Alvarez-Iglesias A, Roshan D, Newell J. Visualising statistical models using dynamic nomograms. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0225253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xu T, Hu L, Xie B, Huang G, Yu X, Mo F, Li W, Zhu M. Analysis of clinical characteristics in patients with diabetic foot ulcers undergoing amputation and establishment of a nomogram prediction model. Sci Rep. 2024;14:27934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lin L, Wang J, Wan Y, Gao Y. [Establishment and evaluation of a nomogram model for predicting the risk of sepsis in diabetic foot patients]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2024;36:693-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang B, Lin T, Wu J, Gong H, Ren Y, Zha P, Chen L, Liu G, Chen D, Wang C, Ran X. [Development and Validation of a Risk Prediction Model for Prolonged Hospitalization in Patients With Diabetic Foot Ulcers]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2024;55:972-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5754] [Cited by in RCA: 9895] [Article Influence: 582.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yuzuguldu B, Zengin B, Simsir IY, Cetinkalp S. An Overview of Risk Factors for Diabetic Foot Amputation: An Observational, Single-centre, Retrospective Cohort Study. touchREV Endocrinol. 2023;19:85-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sánchez CA, Galeano A, Jaramillo D, Pupo G, Reyes C. Risk factors for 30-day hospital readmission in patients with diabetic foot. Foot Ankle Surg. 2025;31:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Matsinhe C, Kagodora SB, Mukheli T, Mokoena TP, Malebati WK, Moeng MS, Luvhengo TE. Machine Learning Algorithm-Aided Determination of Predictors of Mortality from Diabetic Foot Sepsis at a Regional Hospital in South Africa During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60:1718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang S, Xia C, Zheng Q, Wang A, Tan Q. Machine Learning Models for Predicting the Risk of Hard-to-Heal Diabetic Foot Ulcers in a Chinese Population. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2022;15:3347-3359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Syed MH, Al-Omran M, Ray JG, Mamdani M, de Mestral C. High-Intensity Hospital Utilization Among Adults With Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Population-based Study. Can J Diabetes. 2022;46:330-336.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Meloni M, Bouillet B, Ahluwalia R, Sanchez-Rios JP, Iacopi E, Izzo V, Manu C, Julien V, Luedmann C, Garcia-Klepzig JL, Guillaumat J, Lazaro-Martinez JL. Validation of the Fast-Track Model: A Simple Tool to Assess the Severity of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. J Clin Med. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li X, Wen S, Dong M, Yuan Y, Gong M, Wang C, Yuan X, Jin J, Zhou M, Zhou L. The Metabolic Characteristics of Patients at the Risk for Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Comparative Study of Diabetic Patients with and without Diabetic Foot. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023;16:3197-3211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bechara N, Gunton JE, Flood V, Hng TM, McGloin C. Associations between Nutrients and Foot Ulceration in Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Adeleye OO, Ugwu ET, Gezawa ID, Okpe I, Ezeani I, Enamino M. Predictors of intra-hospital mortality in patients with diabetic foot ulcers in Nigeria: data from the MEDFUN study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020;20:134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ha EY, Park IR, Chung SM, Roh YN, Park CH, Kim TG, Kim W, Moon JS. The Potential Role of Presepsin in Predicting Severe Infection in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers. J Clin Med. 2024;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |