INTRODUCTION

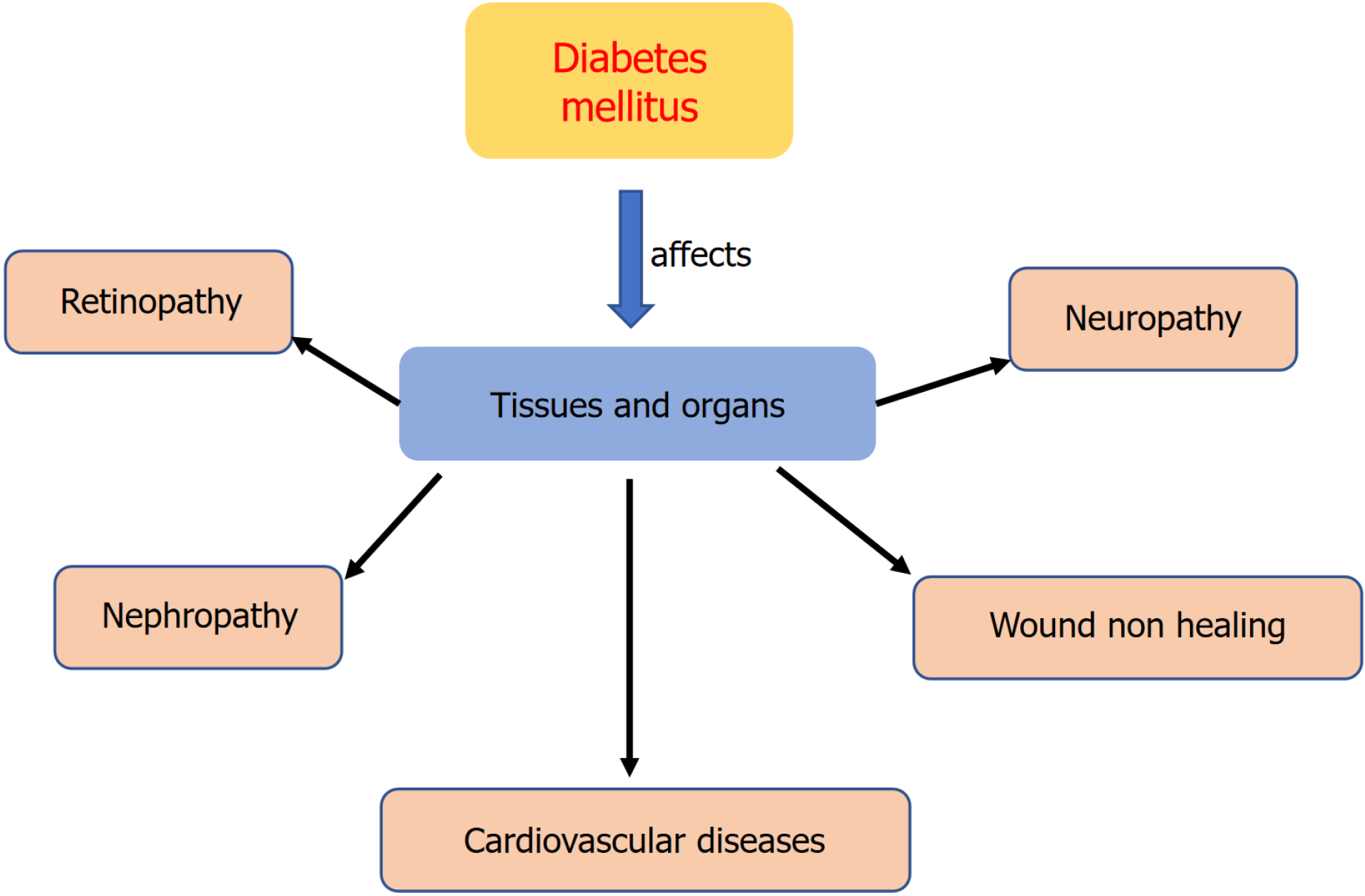

Diabetes mellitus is defined as hyperglycemia in both the fasting and postprandial states[1]. Insulin serves as the primary regulator of blood glucose levels. Insufficient insulin release and suppressed insulin action (named insulin resistance) lead to increased glucose production in the liver and decreased glucose uptake by muscles and fat tissues, resulting in elevated blood glucose concentrations, which are dangerous to human health[2,3]. Hyperglycemia can contribute to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and upregulate markers of inflammation, which ultimately cause tissue dysfunction. Conversely, increased oxidative stress and inflammation further increase insulin resistance and impair insulin secretion[2,4,5]. Diabetes can cause serious health complications. In patients with diabetes, persistent hyperglycemia and disorders of metabolic pathways cause damage to various tissues and organs, which increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and can result in disorders such as diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy (Figure 1)[6-8]. The complications of diabetes are far more harmful than those of diabetes itself[7].

Figure 1 Common complications of diabetes mellitus.

Chronic hyperglycemia stimulates tissues and organs, which causes multiple problems and pathological changes including retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic healing.

Diabetic nephropathy (DN), one of the most important long-term complications of diabetes, is the major cause of end-stage renal disease and high mortality in patients with diabetes[9,10]. Thus, protecting the kidney is very important for patients with diabetes. High blood glucose and oxidative stress are the major contributors to kidney injury; therefore, anti-DN is aimed at inhibiting excess blood glucose and ROS overproduction[1,4].

Glucose is taken up in the kidney via sodium-D-glucose cotransporters (SGLTs), which further maintain high levels of serum glucose to play an important role in diabetic kidney injury. The two most well-known members of the SGLT family are SGLT1 and SGLT2[11]. SGLT1 is located on the apical side of the proximal tubule and facilitates the reabsorption of urinary glucose from the glomerular filtrate. SGLT1 accounts for most of the dietary glucose absorption in the intestine and the renal reabsorption of glucose in the kidney, especially in patients with uncontrolled diabetes and those receiving SGLT2 inhibitors[12,13]. Inhibiting SGLT1 can reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and improve nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by reducing glycogen accumulation and decreasing the production of mitochondrial ROS[13-15]. Currently, novel antidiabetic drugs aimed at lowering blood glucose through the inhibition of SGLT in the intestine and kidney have been developed. Mizagliflozin (MIZ) is a potent, orally active, and selective SGLT1 inhibitor that has been used as an antidiabetic agent that can modify postprandial blood glucose excursion[16-18].

MECHANISMS OF HIGH GLUCOSE TRIGGER OXIDATIVE STRESS AND KIDNEY INFLAMMATORY INJURY

Oxidative stress, which is defined by a disturbance in the balance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses, plays a critical role in cellular physiology and pathophysiology and is associated with the initiation and progression of numerous diseases[19,20]. Chronic oxidative stress induces lipid peroxidation, protein modifications, and DNA damage[21]. Increased ROS generation plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of diabetes, including DN[2]. Mitochondria, as the power plants of cells, play pivotal roles in adenosine triphosphate production and ROS generation. They are extremely sensitive to environmental stimuli, including hypoxia, drugs, toxicity, and changes in nutrient supply[22,23]. Mitochondrial alterations serve as the primary driving force for cellular malfunction before and after insulin resistance[24]. Dysfunctional mitochondria-produced ROS overwhelm intrinsic antioxidant defenses, causing oxidative stress, which can lead to deleterious oxidative damage to DNA, proteins, and membrane lipids and chronic inflammation[25]. Conversely, inflammation can lead to oxidative stress[26].

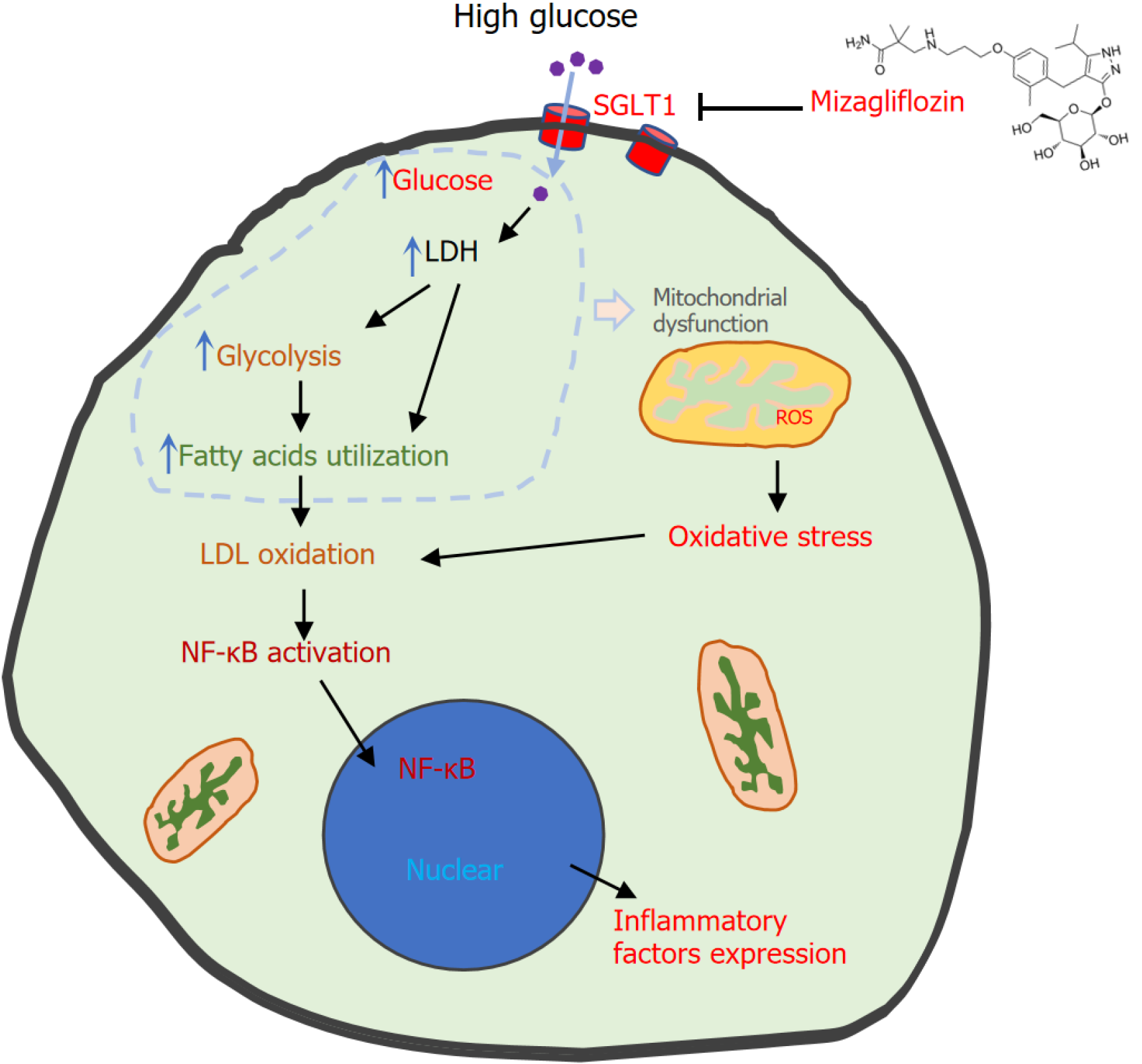

At present, there is strong evidence that the hyperglycemia-induced overproduction of superoxide by the extracellular matrix proteins and attenuated antioxidant defenses are recognized as major causes of the clinical complications associated with diabetes[2,27]. High blood glucose triggers lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) overexpression and enhances the rate of the anaerobic glycolytic pathway, reduces glucose oxidation, and decreases fatty acid β-oxidation[28,29]. Dysfunctional metabolism causes mitochondrial dysfunction, which augments ROS generation. Moreover, long-chain free fatty acid accumulation can inactivate mitochondrial enzymatic activity and hinder electron transport, thus further increasing ROS production, and saturated free fatty acids can also induce chronic inflammation[30-32]. Other metabolic pathways are also involved in oxidative stress development, including the enhanced formation of advanced glycation end products, the hexosamine pathway, the polyol metabolism pathway, and the activation of protein kinase C, which are thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of DN[2,33,34]. Mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming is characterized by mitochondrial biosynthesis dysfunction, increased glycolysis, and abnormal lipid and amino acid metabolism, which significantly influences the pathophysiological progression of DN. Increased fatty acid oxidation in diabetes leads to an increase in the level of oxidized low-density lipoproteins, which activates the nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway[35]. Once activated, it translocates to the nucleus and is bound to a specific section of DNA that triggers the expression of various proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and transforming growth factor beta, and chemokines (Figure 2)[36].

Figure 2 High glucose induces kidney cell injury and the protective effect of mizagliflozin.

High glucose is absorbed into the cytosol and induces lactate dehydrogenase overexpression and thus shifts metabolism (glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation), which causes mitochondrial dysfunction. Dysfunctional mitochondria generate excessive reactive oxygen species, causing oxidative stress. Low-density lipoprotein oxidation leads to nuclear factor kappa B activation, which further triggers the expression of inflammatory factors. Oxidative stress and inflammation contribute to kidney cell injury. Mizagliflozin inhibits sodium-D-glucose cotransporter 1 and changes these processes, thus protecting cells. LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; LDL: Low-density lipoproteins; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa B; ROS: reactive oxygen species; SGLT1: Sodium-D-glucose cotransporter 1.

Glucose levels and metabolite-generated ROS play major roles in the development of various diabetes-related complications. Therefore, antidiabetic therapies are aimed at decreasing blood glucose and oxidative stress[2,37]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of various antioxidants (Q10, α-lipoic acid, coenzymes, and glutathione are the principal intracellular antioxidant buffers against oxidative stress) in the treatment of diabetes mellitus[38,39].

MIZ TARGETS SGLT2 TO DECREASE GLUCOSE REABSORPTION IN THE KIDNEY

MIZ, a potent selective SGLT1 inhibitor, can decrease glucose reabsorption in the kidney. Lin et al[40] reported that “mizagliflozin ameliorates diabetes induced kidney injury by inflammation and oxidative stress”. High glucose increased the expression of SGLT1, LDH, TNF-α/β, and IL-1β and the levels of superoxide dismutase and malondialdehyde and decreased the levels of catalase and glutathione peroxidase. MIZ treatment decreased the protein expression of SGLT1, which decreased glucose reabsorption under high-glucose conditions. It would be better if these effects were supported with SGLT1 knockdown studies. Decreased cellular glucose can normalize glucose metabolism and thus reverse LDH expression and ROS generation[40]. If mitochondrial functions were measured, the authors could see the restoration of those functions. For oxidative stress, it is necessary to analyze the level of ROS, which are the major mediators of oxidative stress, via confocal microscopy or spectrophotometer via the use of mitochondrial ROS or 2’7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate dye. The decreased ROS restored antioxidant defenses and deactivated the nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway, which reduced TNF-α/β and IL-1β expression and apoptosis (should be analyzed in cells). Thus, MIZ effectively ameliorated kidney injury in patients with diabetes (Figure 2).

Compared with canagliflozin, MIZ resulted in greater improvement in LDH levels caused by high glucose. In addition to reducing serum glucose and kidney protection, most SGLT1 and SGLT2 inhibitors provide cardiovascular and liver protection[41]. However, SGLT2 has rarely been detected in human hearts, whereas SGLT1 is highly expressed in the myocardium. As SGLT2 inhibitors also have a moderate inhibitory effect on SGLT1, the cardiovascular protection of SGLT2 inhibitors may be due to SGLT1 inhibition[42].

CONCLUSION

High glucose-induced cellular metabolism triggers mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation in diabetes. Thus, restoring glucose metabolism and mitochondrial function is important for diabetic therapy. Inhibiting glucose absorption and reabsorption through the suppression of SLGT1 plus antioxidants represents a potentially new therapeutic approach in the diabetic mellitus therapeutic process. Given the role of mitochondria in metabolism and ROS generation, future efforts should focus on validating mitochondrial protection mechanisms in DN.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade B, Grade C, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Correa TL; Hu WG; Kehinde SA S-Editor: Luo ML L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xu ZH