Published online Sep 15, 2017. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v9.i9.385

Peer-review started: May 18, 2016

First decision: July 5, 2016

Revised: August 29, 2016

Accepted: September 7, 2016

Article in press: September 8, 2016

Published online: September 15, 2017

Processing time: 481 Days and 12.7 Hours

Desmoid type fibromatosis (DTF) is a rare, locally invasive, non-metastasizing soft tissue tumor. We report an interesting case of DTF involving the pancreatic head of a 54-year-old woman. She presented with intermittent dysphagia and significant weight loss within a 3-mo period. Laboratory findings showed mild elevation of transaminases, significant elevation of alkaline phosphatase and direct hyperbilirubinemia, indicating obstructive jaundice. Computerized tomography of the abdomen revealed a mass in the head of the pancreas, dilated common bile duct, and dilated pancreatic duct. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasound showed a large hypoechoic mass in the head of the pancreas causing extrahepatic biliary obstruction and pancreatic ductal dilation. The patient underwent a successful partial pancreatico-duodenectomy and cholecystectomy. She received no additional therapy after surgery, and liver function tests were normalized within nine days after surgery. Currently, surgical resection is the recommended first line treatment. The patient will be followed for any recurrence.

Core tip: Desmoid type fibromatosis (DTF) is a rare, locally invasive, non-metastasizing soft tissue tumor. We report an extremely rare case of DTF in the pancreatic head with an unusual etiology. This case study is valuable for the understanding of the diagnosis and treatment of DTF of the pancreatic head.

- Citation: Jafri SF, Obaisi O, Vergara GG, Cates J, Singh J, Feeback J, Yandrapu H. Desmoid type fibromatosis: A case report with an unusual etiology. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2017; 9(9): 385-389

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v9/i9/385.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v9.i9.385

Desmoid type fibromatosis (DTF), also known as a desmoid tumor, deep fibromatosis, or aggressive fibromatosis, is a rare, locally invasive, non-metastasizing soft tissue tumor with a high potential for recurrence after resection. It accounts for 3% of all soft tissue tumors[1]. While the etiology is still unknown, it can arise sporadically at any anatomical site throughout the body[2]. DTF is categorized by location as extra-abdominal, abdominal wall, and intra-abdominal.

Intra-abdominal DTF is associated with sites of previous trauma, scarring, or irradiation[3]. An association occurs in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Gardner syndrome, showing 7.5% of patients with DTF to have FAP[4]. To our knowledge, sporadic intra-abdominal DTF cases are very uncommon with only 10 cases having been previously reported, and cases of pancreatic origin being even more uncommon[1,3,5-11].

Here, we report the case of a 54-year-old female patient presenting with obstructive jaundice due to a sporadic DTF, located at the pancreatic head. The patient underwent a successful Whipple procedure and will be followed for any possible recurrence.

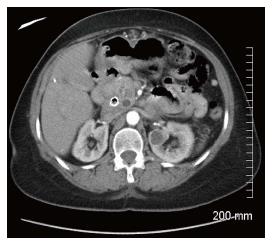

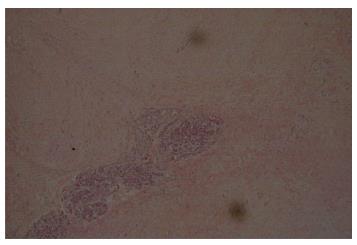

A 54-year-old female presented to the emergency department with intermittent dysphagia and a 60-pound weight loss within a 3-mo period. The patient denied any complaints of nausea or vomiting. Computerized tomography (CT) (Figure 1) of the abdomen revealed a mass in the head of the pancreas, a dilated common bile duct, and a dilated pancreatic duct. Her past surgical history included a total hysterectomy and bilateral tubal ligation. There was no family history to suggest a genetic hereditary disease. Laboratory tests showed mild elevation of transaminases, significant elevation of alkaline phosphatase and direct hyperbilirubinemia, indicating obstructive jaundice. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 was elevated (380 IU/mL) and carcinoembryonic antigen was unremarkable. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed a large 2.5 cm irregular, ill-defined mass at the head of the pancreas causing complete bile and pancreatic duct obstruction. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) (Figure 2) showed a 2.5 cm × 2.2 cm hypoechoic mass in the head of the pancreas causing extrahepatic biliary obstruction and pancreatic ductal dilation. Marked edematous and inflammatory changes were noted around this area. A fine needle aspiration of the pancreatic mass showed predominantly fibrotic, bland spindle cells with scattered normal skeletal muscle components. Immunohistochemical stains for CD117, CD34, and Pancytokeratin were negative. No pancreatic epithelial elements or significant inflammatory infiltrates were noted. Surgery was recommended on the suspicion of a reactive fibroinflammatory pseudotumor. However, surgery was deferred due to underlying pancreatitis.

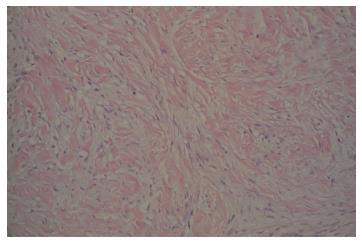

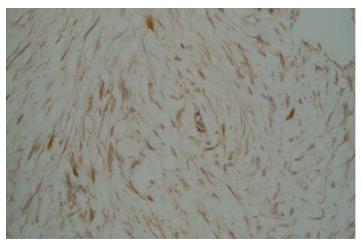

Two months after the emergency department admission, she underwent a new abdominal CT scan, which showed an enlarging of 5.2 cm × 4.2 cm in the pancreatic head. This had not changed significantly on a repeat CT scan after seven weeks. A repeat EUS guided fine needle aspiration was performed due to high suspicion of malignancy. Cytological examination was again negative for epithelial malignancy. Four months after initial presentation, the patient underwent a Whipple procedure with end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy, cholecystectomy, an end-to-side choledochojejunostomy, a wedge liver biopsy of segment 3, a biopsy of the superior pancreatic lymph node, and a retrocolic end-to-end gastrojejunostomy. The procedure was successful, and a feeding jejunal tube was placed. On pathologic microscopic examination, the surgical margins of the liver and lymph node biopsies were negative for a tumor. The pancreatic head lesion showed typical features of DTF. A poorly circumscribed uniform fascicular spindle cell proliferation infiltrates the pancreatic parenchyma among remnants of normal pancreatic epithelial structures (Figure 3). The spindled myofibroblasts exhibit low cellularity and bland cytology (no atypia, no mitosis) with scattered keloid-like collagen and minimal inflammation within a collagenous stroma (Figure 4). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated positive Vimentin (mesenchymal marker) and Actin (focal, patchy, myofibroblast marker). Markers for myogenic cells (Desmin), stromal cells (CD117, CD34), neural cells (S-100) and epithelial cells (Pancytokeratin) were all negative. An initial pathologic impression of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor was made after an additional immunohistochemical stain for ALK-1 was interpreted as showing “staining of spindle cells within the lesion”. However, further consultative review (Gerardo G Vergara) disclosed histologic features more consistent with DTF and the ALK-1 immunostain (faint, patchy staining of spindle cells) was essentially negative. An additional immunostain for Beta-catenin was diffusely nuclear positive (Figure 5), supportive and diagnostic of DTF.

Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor exhibits more cellularity, cellular atypia, more inflammation, and ALK-1 positivity. In reactive fibroblastic/myofibroblastic proliferative lesion, cells are cytologically indistinguishable but architecturally different from fibromatosis and are B-catenin negative. The final diagnosis was therefore changed to DTF.

Recognizing and distinguishing between these lesions are clinically important due to different prognostic and treatment implications, which is key in our case. The patient received no additional therapy after surgery. The patient’s liver function tests normalized within nine days after surgery.

DTF is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm that develops from muscle connective tissue, fasciae, and aponeuroses[12]. Although it is benign, it can be life threatening due to aggressive local invasion, which can result in adverse events through compression and/or obstruction of the digestive system, urinary system, or blood vessels. While the etiology of DTF is unknown, identified risk factors include surgical scars, FAP, and high-estrogen states[13]. And although intra-abdominal DTF is rare, DTF of the pancreas is even rarer, with only 10 cases being reported[1,3,5-11]. Of these 10 reported cases, DTF was located in the pancreatic head in only two cases[3,7].

A confirmed diagnosis of sporadic intra-abdominal DTF is not very probable to be reached before surgery. It is very difficult to diagnose DTF symptomatically. Patients are often asymptomatic or have non-specific symptoms such as weight loss or epigastric pain[4]. Symptoms depend on the location and extent. Painless jaundice, a classic manifestation of pancreatic head cancer, is rarely seen in patients with pancreatic head DTF, as it usually does not obstruct the common bile duct[8]. However, in our case, the patient had painless jaundice due to the obstruction of the common bile duct.

Additionally, the patient had an elevated aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin. ERCP and EUS both showed a mass in the head of the pancreas causing extrahepatic biliary obstruction and pancreatic ductal dilation. Dilation of the pancreatic duct is usually indicative of pancreatic adenocarcinoma[14]. According to Tummala et al[14], in 81.2% of patients with dilation of the pancreatic duct associated with a pancreatic lesion, the lesion was found to be malignant with pancreatic adenocarcinoma comprising the majority (71.6%) of the lesions.

Due to a high suspicion of malignancy, fine needle aspiration of the pancreatic mass was done. However, a definitive diagnosis was not possible. After repeat testing yielded the same results, a reactive fibroinflammatory pseudotumor was suspected. A fibroinflammatory pseudotumor radiographically presents as a mass that resembles a carcinoma or a sarcoma[15]. There have been a number of reported inflammatory pseudotumors of the pancreas, which were frequently localized in the head of the pancreas, were fibrous in appearance, and involved the distal bile duct[15]. The definitive diagnosis of such psuedotumors is usually obtained through a total or partial surgical resection[16].

Histologically, differentiation of DTF from other soft tissue neoplasms can sometimes be challenging, particularly when it occurs in an uncommon site (in our case, the pancreas) or with a low index of suspicion. DTF typically consists of spindle cells and fibroblasts with a low mitotic rate[17]. However, reaching a confirmed diagnosis is still unlikely until surgery is performed with total tumor removal, as in the case of an inflammatory pseudotumor. Immunohistochemistry against specific cell markers in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic DTF is useful, supportive and diagnostic. Positive staining for Vimentin and Actin are indicative of mesenchymal cells and myofibroblasts, respectively, while positive staining for beta-catenin helps distinguish DTF from other fibroblastic and myofibroblastic lesions[18]. In 80%-90% of sporadic cases, somatic mutations of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene and activating mutations in CTNNB1 (beta-catenin gene) usually result in the accumulation of beta-catenin. This accumulation triggers fibroblastic proliferation[19]. This was relevant in our case, as the initial diagnosis was inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor was later changed to DTF.

The mainstay treatment for DTF is surgery with wide microscopic resection of the margins[20]. However, there is a very high chance of local recurrence with surgical resection. Long-term prognosis is currently unknown. Recurrence of pancreatic DTF has not been seen except in one patient with FAP[9]. In the current case, the patient will be followed for any possible recurrence and possible work up for FAP.

In conclusion, sporadic DTF of the pancreas is extremely rare. Although it is benign, it is locally aggressive and can be life threatening. Since it can be asymptomatic or present with non-specific symptoms, diagnosis can be difficult clinically or by imaging studies and requires adequate tissue sample, high index of suspicion, and recognition of typical histopathology and immunohistochemistry. Distinguishing this lesion from other lesions is clinically significant, both for prognosis and treatment decision-making. First line treatment is surgical resection. As there is a high chance of local recurrence and an unknown long-term prognosis, follow-up is necessary.

A 54-year-old female presenting with intermittent dysphagia and a 60-pound weight loss within a 3-mo period.

Desmoid type fibromatosis (DTF) of the pancreatic head.

Reactive fibroinflammatory pseudotumor, pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Obstructive jaundice.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showed a large 2.5 cm irregular, ill-defined mass at the head of the pancreas causing complete bile and pancreatic duct obstruction. Endoscopic ultrasound (Figure 2) showed a 2.5 cm × 2.2 cm hypoechoic mass in the head of the pancreas causing extrahepatic biliary obstruction and pancreatic ductal dilation. Computed tomography showed a persistent mass of 5.2 cm × 4.2 cm in the pancreatic head.

DTF.

Successful surgical resection with no complicaitons.

Sporadic DTF of the pancreas is extremely rare.

Although DTF of the pancreas is benign, it is locally aggressive and can be life threatening. As there is a high chance of local recurrence and an unknown long-term prognosis, follow-up is necessary.

This manuscript was reported about a rare case of DTF at the pancreatic head.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kainuma O, Xu Z S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Amiot A, Dokmak S, Sauvanet A, Vilgrain V, Bringuier PP, Scoazec JY, Sastre X, Ruszniewski P, Bedossa P, Couvelard A. Sporadic desmoid tumor. An exceptional cause of cystic pancreatic lesion. JOP. 2008;9:339-345. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Fisher C, Thway K. Aggressive fibromatosis. Pathology. 2014;46:135-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jia C, Tian B, Dai C, Wang X, Bu X, Xu F. Idiopathic desmoid-type fibromatosis of the pancreatic head: case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nieuwenhuis MH, Casparie M, Mathus-Vliegen LM, Dekkers OM, Hogendoorn PC, Vasen HF. A nation-wide study comparing sporadic and familial adenomatous polyposis-related desmoid-type fibromatoses. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:256-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Roggli VL, Kim HS, Hawkins E. Congenital generalized fibromatosis with visceral involvement. A case report. Cancer. 1980;45:954-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bruce JM, Bradley EL, Satchidanand SK. A desmoid tumor of the pancreas. Sporadic intra-abdominal desmoids revisited. Int J Pancreatol. 1996;19:197-203. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sedivy R, Ba-Ssalamah A, Gnant M, Hammer J, Klöppel G. Intraductal papillary-mucinous adenoma associated with unusual focal fibromatosis: a “postoperative” stromal nodule. Virchows Arch. 2002;441:308-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nursal TZ, Abbasoglu O. Sporadic hereditary pancreatic desmoid tumor: a new entity? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:186-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pho LN, Coffin CM, Burt RW. Abdominal desmoid in familial adenomatous polyposis presenting as a pancreatic cystic lesion. Fam Cancer. 2005;4:135-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Weiss ES, Burkart AL, Yeo CJ. Fibromatosis of the remnant pancreas after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:679-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Polistina F, Costantin G, D’Amore E, Ambrosino G. Sporadic, nontrauma-related, desmoid tumor of the pancreas: a rare disease-case report and literature review. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010:272760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stanek K. Intra-abdominal Desmoid Tumor. J Diagn Med Sonog. 2007;23:212-14. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Laufer I, Wolinsky JP, Gokaslan ZL. Desmoid tumors. World Neurosurg. 2013;79:97-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tummala Md P, Rao Md S, Agarwal Md B. Differential Diagnosis of Focal Non-Cystic Pancreatic Lesions With and Without Proximal Dilation of Pancreatic Duct Noted on CT Scan. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2013;4:e42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zamboni G, Capelli P, Scarpa A, Bogina G, Pesci A, Brunello E, Klöppel G. Nonneoplastic mimickers of pancreatic neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:439-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lopez-Tomassetti Fernandez EM, Luis HD, Malagon AM, Gonzalez IA, Pallares AC. Recurrence of inflammatory pseudotumor in the distal bile duct: lessons learned from a single case and reported cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3938-3943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nakayama T, Tsuboyama T, Toguchida J, Hosaka T, Nakamura T. Natural course of desmoid-type fibromatosis. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bhattacharya B, Dilworth HP, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Ricci F, Weber K, Furlong MA, Fisher C, Montgomery E. Nuclear beta-catenin expression distinguishes deep fibromatosis from other benign and malignant fibroblastic and myofibroblastic lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:653-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cheon SS, Cheah AY, Turley S, Nadesan P, Poon R, Clevers H, Alman BA. beta-Catenin stabilization dysregulates mesenchymal cell proliferation, motility, and invasiveness and causes aggressive fibromatosis and hyperplastic cutaneous wounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6973-6978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Colombo C, Gronchi A. Desmoid-type fibromatosis: what works best? Eur J Cancer. 2009;45 Suppl 1:466-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |