Published online Sep 15, 2017. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v9.i9.354

Peer-review started: April 13, 2017

First decision: May 8, 2017

Revised: May 13, 2017

Accepted: May 30, 2017

Article in press: May 31, 2017

Published online: September 15, 2017

Processing time: 150 Days and 22.3 Hours

To investigate the importance of a three-tiered histologic grade on outcomes for patients with mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma (MAA).

Two hundred and sixty-five patients with MAA undergoing cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy were identified from a prospective database from 2004 through 2014. All pathology was reviewed by our gastrointestinal subspecialty pathologists and histological grade was classified as well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated. Survival analysis was performed using Cox proportional hazards regression.

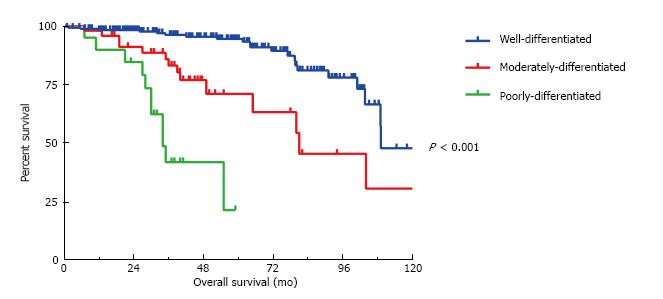

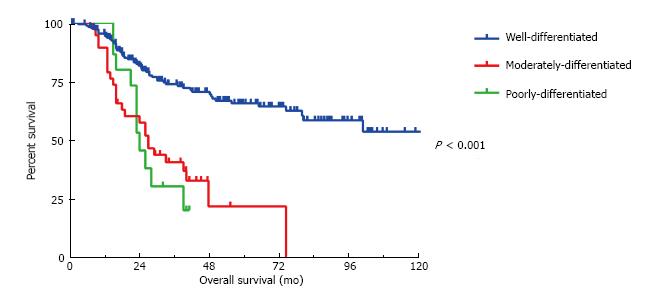

There were 201 (75.8%) well-, 45 (16.9%) moderately- and 19 (7.2%) poorly-differentiated tumors. Histological grade significantly stratified the 5-year overall survival (OS), 94%, 71% and 30% respectively (P < 0.001) as well as the 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) 66%, 21% and 0%, respectively (P < 0.001). Independent predictors of DFS included tumor grade (HR = 1.78, 95%CI: 1.21-2.63, P = 0.008), lymph node involvement (HR = 0.33, 95%CI: 0.11-0.98, P < 0.02), previous surgical score (HR = 1.31, 95%CI: 1.1-1.65, P = 0.03) and peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI) (HR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.02-1.08, P = 0.002). Independent predictors of OS include tumor grade (HR = 2.79, 95%CI: 1.26-6.21, P = 0.01), PCI (HR = 1.10, 95%CI: 1.03-1.16, P = 0.002), and complete cytoreduction (HR = 0.32, 95%CI: 0.11-0.92, P = 0.03). Tumor grade and PCI were the only independent predictors of both DFS and OS. Furthermore, histological grade and lymphovascular invasion stratified the risk of lymph node metastasis into a low (6%) and high (40%) risk groups.

Our data demonstrates that moderately differentiated MAA have a clinical behavior and outcome that is distinct from well- and poorly-differentiated MAA. The three-tier grade classification provides improved prognostic stratification and should be incorporated into patient selection and treatment algorithms.

Core tip: The natural history of mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma encompasses a wide spectrum of clinical outcomes. This study illustrates that classification of these tumors using tumor cellularity, architectural features and cytologic abnormalities into three distinct histological grades; well-, moderately- and poorly-differentiated allows the clinician to better estimate relative risk of recurrence and death. Thus facilitating patient selection, education and comparison of different treatments.

- Citation: Grotz TE, Royal RE, Mansfield PF, Overman MJ, Mann GN, Robinson KA, Beaty KA, Rafeeq S, Matamoros A, Taggart MW, Fournier KF. Stratification of outcomes for mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma with peritoneal metastasis by histological grade. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2017; 9(9): 354-362

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v9/i9/354.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v9.i9.354

Mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma (MAA) is a rare tumor. The vast majority of these lesions are thought to arise from low-grade appendiceal neoplasms which have a unique biological predisposition for peritoneal spread, with rare lymphatic and hematogenous metastasis. These tumors can produce abundant mucin causing abdominal distension and the clinical condition known as pseudomyxoma peritonei. The spectrum of biological aggressiveness of these tumors varies widely leading to difficulties in classification of both the primary tumor and secondary peritoneal metastasis. This has led to confusing nomenclature. Ronnett et al[1], in a retrospective review proposed a three-tier staging system according to the histology of the peritoneal disease rather than the primary. Peritoneal tumors with abundant extracellular mucin containing scant, simple to focally proliferative, mucinous epithelium, with little cytological atypia or mitotic activity was classified as diffuse peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM). In contrast, peritoneal tumors composed of more abundant mucinous epithelium with the architectural and cytological features of carcinoma were classified as peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis (PMCA). Peritoneal tumors with a histology intermediate to DPAM and PMCA were classified as PMCA-Intermediate[1]. This classification stratified tumor behavior well and has been supported by others[2-4]. Others have proposed a two tier system combining either the intermediate and high grade groups or the intermediate and low-grade groups because of their presumed similar prognosis[5,6].

A consensus statement published in 2008 highlighted the controversy as 44% of participants used the Ronnett three-tier classification and the remaining 56% used a two-tier classification system[5]. In the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging Manual, appendiceal carcinomas are now classified separately from colorectal carcinomas[7]. Currently, the histologic grading scheme endorsed by AJCC is unclear. The AJCC staging form allows for a 2-, 3-, or 4-tier system while the staging criterion to stratify stage IV disease appears to use a three-tier system (designated by “G”). Comparisons of these systems are made under the grade explanation, with G1 and well-differentiated corresponding to “mucinous low grade” and G2/G3 and moderately to poorly differentiated corresponding to “mucinous high grade”. G4 corresponds to an undifferentiated tumor. Within the AJCC system currently in use, there is no distinction between mucinous tumors arising from a low-grade appendiceal neoplasm and the less common MAA showing conventional colonic-type features (infiltrating glands associated with destructive invasion and desmoplasia), although, this distinction has begun to be recognized in the 8th edition of the AJCC Staging manual[7].

These challenges and controversies were discussed at the 2012 World Congress of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) in Berlin where an expert panel achieved a consensus using a three-tier system using both histological grade and signet ring cell morphology; low grade, high grade and high grade with signet ring cells[8]. However, a recent investigation of the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result (SEER) database did not support the merging of moderately and poorly differentiated grades into a single high-grade category as moderately differentiated tumors had a survival that was intermediate to well differentiated and poorly differentiated tumors[9]. Therefore, we sought to evaluate our outcomes following cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) according to the degree of metastatic tumor differentiation.

This study was approved by an Institutional Review Board at University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center. Consecutive patients with MAA, who underwent CRS and HIPEC at our institution between January 2004 and December 2014, were identified from a prospectively maintained database. All patient evaluations included a complete history and physical exam, laboratory studies, assessment of tumor markers (CA 19-9, CA-125 and CEA) and imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. All pathology was reviewed by our gastrointestinal subspecialty pathologists and histological grade was classified as well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated based on tumor cellularity, architectural features (strips of cells, clustering, complex architecture such as cribriform structures, papillae, or pseudopapillae), and cytologic abnormalities (nuclear polarity, presence of mitotic figures and/or apoptotic bodies, nuclear size, and chromatin characteristics). If signet ring cells within mucin were not a significant component of the tumor (i.e., less than 10% of the neoplastic cells), these were not incorporated into the grade but were annotated. In general, well-differentiated MAA are paucicellular, consisting mostly of strips of epithelium with little complexity and bland to slightly atypical cytologic features. Poorly differentiated MAA showed cellular tumors with clusters of tumor cells within (instead of, or in addition to, lining) mucin pools. The neoplastic epithelium has either easily identifiable cytologic atypia (enlarged nuclei, open chromatin, apoptotic bodies, loss of polarity) and/or architectural complexity, and/or loss of cohesion (clusters of neoplastic cells and/or abundant single cells). Moderately differentiated MAA often have features in between these two ends of the spectrum. When tumor heterogeneity is present between different specimens in the same case, the highest grade was utilized for analysis. CRS and HIPEC was performed in our standard closed fashion with Mitomycin C (20-25 mg/m2) for 90 min at 40.5 °C, as previously described[10].

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and proportions for categorical data, and medians and interquartile range for continuous outcomes were calculated for all study measures. Associations between categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Overall survival (OS) was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. OS was calculated from the date of first treatment to the date of death or last follow up. Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated from the date of CRS and HIPEC to time of first recurrence identified on imaging. Multivariate analysis was performed with Cox regression analysis in which a backward elimination process was used for variable selection with an entry and removal limit of P < 0.1 and P < 0.05, respectively. All analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). All graphs were made using GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, United States, http://www.graphpad.com). All P-values were two-sided and a P value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Baseline, clinical and pathological characteristics for the entire cohort are stratified by histological grade and are reported in Table 1. Two hundred and sixty-five patients with MAA undergoing CRS and HIPEC were identified. Preoperative diagnosis was confirmed in all patients. A percutaneous biopsy or laparoscopic biopsy/appendectomy was performed in 104 (39.2%). A pre-referral laparotomy with limited resection was performed in 75 (28.3%) and previous (pre-referral) extended resection was performed in 59 (22.3%) and cytoreduction in 27 (10.2%). The pre-operative pathology was classified as well differentiated in 198 (73.9%) patients, moderately differentiated in 49 (18.3%) patients and poorly differentiated in 18 (6.7%) patients. The pre-operative pathology was discordant with the pathology at the time of CRS and HIPEC in 32 (12.1%) patients. In 14 (43.8%) the pathology was downgraded at the time of CRS and in 18 (56.3%) it was upgraded.

| Characteristics of the entire cohort (n = 265) | Well-differentiated (n = 201) | Moderately-differentiated (n = 45) | Poorly-differentiated (n = 19) | Total | P value |

| Age | 53.1 (45-59) | 54.9 (46-59) | 49.6 (45-60) | 53.4 (45-59) | P = 0.963 |

| Sex | P = 0.622 | ||||

| Male | 78 (39) | 21 (47) | 8 (42) | 107 (40.4) | |

| Female | 123 (61) | 24 (53) | 11 (58) | 158 (59.6) | |

| Signet ring cell | P < 0.00112 | ||||

| > 50% | 0 | 3 (7) | 11 (58) | 14 (5.3) | |

| 1%-50% | 6 (3) | 4 (9) | 0 | 10 (3.8) | |

| None | 195 (97) | 38 (84) | 8 (42) | 241 (90.9) | |

| LVI | P < 0.00112 | ||||

| Yes | 3 (1) | 8 (18) | 9 (47) | 20 (7.5) | |

| No | 198 (98) | 35 (78) | 3 (16) | 241 (90.9) | |

| LN involvement | P < 0.00112 | ||||

| Yes | 11 (5) | 4 (9) | 8 (42) | 23 (8.7) | |

| No | 160 (80) | 38 (84) | 4 (21) | 208 (78.5) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemo | P < 0.00112 | ||||

| Yes | 29 (14) | 21 (47) | 15 (79) | 65 (24.5) | |

| No | 172 (86) | 24 (53) | 4 (21) | 200 (75.5) | |

| Adjuvant chemo | P < 0.00112 | ||||

| Yes | 12 (6) | 3 (7) | 8 (42) | 23 (8.7) | |

| No | 189 (94) | 42 (93) | 11 (58) | 242 (91.3) | |

| PSS | P = 0.0522 | ||||

| 0 | 77 (38) | 20 (44) | 7 (37) | 104 (39.2) | |

| 1 | 59 (29) | 13 (29) | 3 (16) | 75 (28.3) | |

| 2 | 44 (22) | 6 (13) | 9 (47) | 59 (22.3) | |

| 3 | 21 (10) | 6 (13) | 0 | 27 (10.2) | |

| Albumin | 4.2 (4.0-4.4) | 4.3 (4.1-4.5) | 4.2 (4.0-4.9) | 4.2 (4.1-4.5) | P = 0.773 |

| CEA | 2.8 (1.3-10.7) | 4.5 (2.4-15.7) | 2.2 (1.4-4.9) | 3.4 (1.5-10.5) | P = 0.923 |

| PCI | 17.5 (11-26) | 14 (8-24) | 15.5 (12-25) | 16.5 (10-25) | P = 0.453 |

| Completeness of cytoreduction | P = 0.322 | ||||

| CC 0-1 | 176 (88) | 40 (89) | 15 (79) | 231 (87.2) | |

| CC 2-3 | 19 (9) | 5 (11) | 4 (21) | 28 (10.6) | |

| Unknown | 6 (2.3) | ||||

| OR time | 9.2 (7.7-11.4) | 8.7 (6.9-10.0) | 7.9 (6.9-10.5) | 8.9 (7.5-11.1) | P = 0.823 |

| Blood loss | 600 (350-997) | 375 (250-588) | 350 (250-550) | 500 (300-900) | P = 0.00713 |

| LOS | 19 (13-27) | 13 (10-22) | 16 (10-23) | 17 (12-26) | P = 0.00813 |

| 30 d morbidity any grade | 108 (54) | 28 (68) | 11 (58) | 149 (55) | P = 0.492 |

| 90 d grade III/IV | 35 (17) | 14 (31) | 2 (10) | 51 (19.2) | P = 0.352 |

| 90 d mortality | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.8) | P = 0.732 |

At the time of cytoreduction 34 (12.8%) patients had acellular mucin only; 167 (63.0%) had well differentiated MAA; 45 patients had moderately differentiated MAA and 19 patients had poorly differentiated MAA. Figure 1 illustrates the 5-year OS is 94%, 71% and 20% respectively (P < 0.001). Similarly, the 5-year DFS is 66%, 21% and 20%, respectively (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). Regardless of the initial pathology, the finding of acellular mucin only at time of CRS and HIPEC was associated with a 93% 5-year DFS and 100% 5-year OS. Important prognostic variables for DFS on multivariate analysis (Table 2) include: Tumor grade (HR = 1.78, 95%CI: 1.21-2.63, P = 0.008), lymph node involvement (HR = 0.33, 95%CI: 0.11-0.98, P < 0.02), previous surgical score (PSS) (HR = 1.31, 95%CI: 1.1-1.65, P = 0.03) and PCI (HR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.02-1.08, P = 0.002). Important prognostic factors for OS on multivariate analysis (Table 2) include: Tumor grade (HR = 2.79, 95%CI: 1.26-6.21, P = 0.01), PCI (HR = 1.10, 95%CI: 1.03-1.16, P = 0.002), and complete cytoreduction (HR = 0.32, 95%CI: 0.11-0.92, P = 0.03). Tumor grade and PCI were the only independent predictors of both DFS and OS.

| Disease-free survival | Overall survival | ||||||

| Univariate | P value | Multivariate (HR, 95%CI) | P value | Univariate | P value | Multivariate (HR, 95%CI) | P value |

| Age | 0.45 | Age | 0.35 | ||||

| Sex | 0.051 | 0.59 | Sex | < 0.0011 | 0.13 | ||

| Albumin | 0.27 | Albumin | 0.28 | ||||

| ECOG status | 0.38 | ECOG status | 0.0061 | 0.15 | |||

| Pre-op CEA | 0.39 | Pre-op CEA | 0.07 | 0.51 | |||

| Grade | < 0.0011 | 1.8 (1.2-2.8) | 0.0081 | Grade | < 0.0011 | 2.80 (1.26-6.21) | 0.011 |

| Signet ring cell | < 0.0011 | 0.828 | Signet ring cell | < 0.0011 | 0.22 | ||

| Lympho-vascular invasion | < 0.0011 | 0.15 | Lympho-vascular invasion | < 0.0011 | 0.82 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | < 0.0011 | 0.42 (0.20-0.88) | 0.021 | Lymph node metastasis | < 0.0011 | 0.47 | |

| PSS | 0.09 | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 0.031 | PSS | 0.14 | ||

| PCI | 0.031 | 1.05 (1.02-1.08) | 0.0021 | PCI | < 0.001 | 1.10 (1.03-1.16) | 0.0021 |

| CC0 resection | < 0.0011 | 0.32 (0.11-0.92) | 0.03 | ||||

All three histological grades were significantly different from each other in terms of overall survival (all P < 0.001). However, in terms of disease-free survival the moderately differentiated tumors were significantly different (P < 0.001) from the well-differentiated but not the poorly differentiated tumors (P = 0.31).

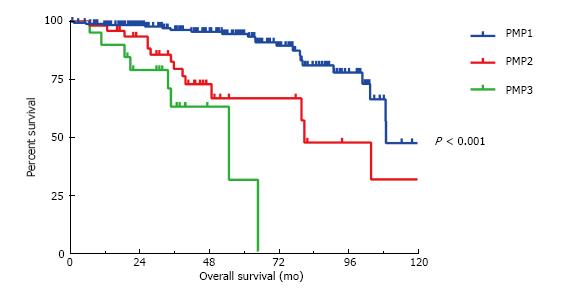

The presence of signet rings cells was significant predictor of OS on univariate but not multivariate analysis and therefore the tumors were alternatively classified according to Shetty classifications of well differentiated (PMP1) and moderately and poorly differentiated MAA without signet ring cells (PMP2) and with signet ring cells (PMP3). The median OS for the three groups are 109 mo, 81 mo and 55 mo, respectively (P < 0.001) (Figure 3). However, the presence or absence of signet ring cells failed to significantly stratify survival outcomes between the PMP2 and the PMP3 categories in regards to DFS (P = 0.76) and OS (P = 0.08). Patients with < 50% signet rings cells did similarly as poor as those with > 50% signet ring cells (median OS 43 mo vs 34 mo) when compared to those without signet rings cells (median OS 109 mo) (P < 0.001 when comparing < 50% signet rings cells to no signet ring cells and when comparing > 50% signet ring cells to no signet ring cells. No statistical difference between those with < 50% signet ring cells and those with > 50% signet rings cells, P = 0.64).

The presence of lymph node metastasis varied by histological grade (P < 0.001) but not by the presence of signet ring cells (P = 0.08). Lymphovascular invasion was also a significant predictor of nodal positivity and significantly stratified the risk of lymph node metastasis for the moderately-differentiated MAA (Table 3). Moderately-differentiated MAA without lymphovascular invasion had the same low incidence of lymph node metastasis as the well-differentiated tumors. In contrast, the moderately-differentiated MAA with lymphovascular invasion had the same high incidence of lymph node metastasis as the poorly-differentiated MAA.

| Incidence of lymph node metastasis | ||

| Histological grade | P < 0.001 | |

| Well-differentiated | 5.50% | |

| Moderately-differentiated | 10.80% | |

| Poorly-differentiated | 42.10% | |

| Signet ring cell | P = 0.08 | |

| Absent | 7.50% | |

| Present | 20.80% | |

| Moderately-differentiated and LVI- | 6% | P = 0.008 |

| Moderately-differentiated and LVI+ | 40% |

This analysis highlights the important prognostic distinction of an intermediate classification for MAA based on histological grade alone. Although histological grade has previously been demonstrated to have a major prognostic impact on survival, most authors combine either the intermediate and high grade groups or the intermediate and low grade groups because of their presumed similar prognosis. The 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual recognized the significance of histological grade and incorporated it into the staging classification of MAA[11]. While there is a suggestion by the WHO[12] and AJCC[7], as well as other authors[5,6], to use a two-tiered system, this is not supported by a population based study utilizing the SEER database which demonstrated that moderately differentiated MAA have a distinctly different clinical behavior than that of well differentiated and poorly differentiated MAA[13]. Similarly, we found moderately differentiated MAA have a survival intermediate to well and poorly differentiated MAA and should be categorized separately.

The unique biological behavior of MAA makes classification of both the primary tumor and metastatic peritoneal spread difficult and there has been considerable debate in the literature about the correct terminology[1,2,4,6]. Unfortunately, the end result has been a variety of different proposed classifications that has led to confusion within the literature and among treating clinicians. Issues that plague grading schema include subjectivity, sampling, tumor characteristics, tumor heterogeneity, and even recognition of differing biologic behaviors depending on the appendiceal primary. Unfortunately, grading relies often on subjective observation rather than objective measurement; although attempts have been made to provide objective criteria, it can be difficult in these tumors[14]. Tumor heterogeneity between sites, or even within the same site, in a patient is not uncommon. Because of this, sampling artifact can be problematic both at the clinical level (needle biopsy vs larger biopsy) or at the time of pathologic dissection. Histologic characteristics also play a role. While most of the mucinous tumors arise in a background of low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMN), a smaller percentage of MAA arise either de novo (possibly obliterating the precursor lesion) or in association with an adenoma and have the appearance of a mucinous type colonic adenocarcinoma. The latter lesions may have more gland formation, allowing categorization into a “moderately differentiated”/intermediate grade category. These tumors are much more likely to show lymphovascular invasion and lymph node metastases. In an attempt to standardize terminology and clarify histological classification the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) formed an international expert panel to achieve a consensus. Within the expert panel there were 6 different classification systems used. The final recommendations were similar to the Shetty classification in which low grade tumors consist of well-differentiated MAA and the moderately and poorly differentiated MAA are grouped into a high grade category stratified by the presence of signet ring cells[8]. However, the definition of signet ring cells is inconsistent. The Shetty classification defined signet ring cells as any percentage of signet ring cells. Other reports suggest that only infiltrative signet ring cells are prognostic and not degenerative cells floating in mucin, which may mimic signet ring cells[14,15]. AJCC and the PSOGI consensus utilized the WHO classification of signet ring cell adenocarcinoma which is defined as a tumor composed of > 50% of cells. In the current study, we found that the presence of any degree of signet ring cells was prognostic not just those with > 50% signet ring cells. Furthermore, we found that histological grade not signet ring cells was an independent predictor of DFS. Histological grade also stratified nodal metastasis risk and signet ring cells did not. Our data is unique in that we found a truly intermediate prognosis for the moderately differentiated MAA. Also we demonstrate the importance of histological grade as it was the only independent predictor of both DFS and OS. Therefore, we conclude that histological grade is superior to the presence of signet ring cells in stratifying both DFS and OS and should be incorporated into the AJCC staging criteria for stage IV MAA.

Consistently differentiating and reporting MAA into unambiguous histological classifications is imperative as they reflect the divergent biology of the tumor. This information may be then used to develop the divergent treatment approaches that are employed. For example, well-differentiated MAA are likely to behave in an indolent fashion and therefore, aggressive cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with the intent of removing all tumor burden to ≤ 2.5 mm has been demonstrated to substantially prolong survival[16]. However, adjuvant systemic chemotherapy has been demonstrated to provide no benefit for well-differentiated tumors[17]. In contrast, poorly-differentiated MAA which are likely to behave aggressively derive survival benefit from adjuvant systemic chemotherapy and the aggressiveness of surgical cytoreduction must be carefully weighed against the morbidity and reduced probability of long-term survival. Moderately-differentiated MAA exhibit an intermediate biology that appears to respond to systemic chemotherapy[17] and warrant a more aggressive approach to surgical cytoreduction given the higher likelihood of long-term survival[18].

Furthermore, performing a right hemicolectomy is predicated on the risk of lymph node metastasis. Our data demonstrates that the risk of lymph node metastasis is well stratified by the histological grade and presence of lymphovascular invasion. Well-differentiated MAA have a low risk of nodal metastasis and therefore a right hemicolectomy is unwarranted. In contrast, a poorly-differentiated MAA has a 40% incidence of lymph node metastasis and a right hemicolectomy is indicated. As anticipated a moderately differentiated tumor has an incidence of lymph node metastasis that is intermediate to the well- and poorly-differentiated tumors. However, our data suggests that the presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion further stratifies risk such that moderately-differentiated MAA without lymphovascular invasion demonstrate the same low incidence of nodal metastasis is as well-differentiated MAA and therefore no colectomy is warranted. In contrast, moderately-differentiated MAA with lymphovascular invasion have a high incidence of lymph node metastasis similar to poorly-differentiated MAA and therefore a right hemicolectomy is warranted.

We recognize there are significant limitations to the study as in all retrospective single institutional reports including the small sample size, selection bias and non-uniformity of treatment. In addition, while the grade was determined prospectively by our group of subspecialized gastrointestinal pathologists, the cases were not re-reviewed by a single pathologist to eliminate interobserver variability. However, potential strengths of this study include the large sample size, consistent reporting of histological grade, lymphovascular invasion, and presence of signet ring cells in order to inform standardized care, and the long-term follow up.

In conclusion, histological grade is independently associated with DFS and OS and accurately predicts risk of nodal metastasis. Our data supports a three-tier histological grading system for peritoneal carcinomatosis from MAA. This classification best stratifies survival outcomes and should be incorporated into patient selection and treatment algorithms and potentially into future AJCC staging updates. The 8th edition of the AJCC staging system currently groups grade G2 and G3 (moderate and poorly differentiated) MAA into the same Stage IVB group. Our data suggests a separate Stage IV for each grade may be more appropriate.

The authors would like to acknowledge Sun and Do Lee, Harold Allen and Andrew Schroeder for their contribution to GI Cancer Research at MD Anderson.

The authors’ understanding of mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma (MAA) is plagued by confusing and indescript terminology, which does not capture the heterogeneous biology and outcomes of these tumors. There remains an unmet need for further investigation of the clinical behavior and outcomes of clearly defined histological classifications.

Survey results show that even amongst experts at high volume centers there is considerable discrepancy in the terminology and classification of MAA. A consensus conference was unable to agree on a single terminology and the AJCC staging system allows both two and three-tiered grading system. Further evidence is necessary to bring clarification to this field.

This is one of the largest single institutional investigations of MAAs with consistent and clearly defined histological grading and the associated long-term outcomes following cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). The data demonstrates that moderately differentiated carcinomas have a clinical behavior and outcome that is distinct from well- and poorly-differentiated carcinomas.

The three-tier grade classification provides improved prognostic stratification and should be incorporated into patient selection and treatment algorithms and potentially into future AJCC staging updates. The 8th edition of the AJCC staging system currently groups grade G2 and G3 (moderate and poorly differentiated) MAA into the same Stage IVB group. The data suggests a separate Stage IV for each grade may be more appropriate.

CRS involves a full midline laparotomy and systematic evaluation of the entire peritoneal surface including all recesses. All visible tumor is then removed by means of peritonectomy or resection of underlying organs. HIPEC is the subsequent administration of high dosages of chemotherapy into the peritoneum under hyperthermia (40 °C-42 °C) for 60-90 min under constant agitation.

This article is to investigate the importance of a three-tiered histologic grade on outcomes for patients with MAA. The study is good.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Barreto S, Tang Y, Tsikouras PPT S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ronnett BM, Zahn CM, Kurman RJ, Kass ME, Sugarbaker PH, Shmookler BM. Disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis and peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis. A clinicopathologic analysis of 109 cases with emphasis on distinguishing pathologic features, site of origin, prognosis, and relationship to “pseudomyxoma peritonei”. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1390-1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 599] [Cited by in RCA: 545] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ronnett BM, Yan H, Kurman RJ, Shmookler BM, Wu L, Sugarbaker PH. Patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei associated with disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis have a significantly more favorable prognosis than patients with peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis. Cancer. 2001;92:85-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bruin SC, Verwaal VJ, Vincent A, van’t Veer LJ, van Velthuysen ML. A clinicopathologic analysis of peritoneal metastases of colorectal and appendiceal origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2330-2340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shetty S, Natarajan B, Thomas P, Govindarajan V, Sharma P, Loggie B. Proposed classification of pseudomyxoma peritonei: influence of signet ring cells on survival. Am Surg. 2013;79:1171-1176. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Moran B, Baratti D, Yan TD, Kusamura S, Deraco M. Consensus statement on the loco-regional treatment of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms with peritoneal dissemination (pseudomyxoma peritonei). J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:277-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bradley RF, Stewart JH, Russell GB, Levine EA, Geisinger KR. Pseudomyxoma peritonei of appendiceal origin: a clinicopathologic analysis of 101 patients uniformly treated at a single institution, with literature review. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:551-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Edge SB. American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual. New York: Springer 2010; . |

| 8. | Carr NJ, Cecil TD, Mohamed F, Sobin LH, Sugarbaker PH, González-Moreno S, Taflampas P, Chapman S, Moran BJ. A Consensus for Classification and Pathologic Reporting of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei and Associated Appendiceal Neoplasia: The Results of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) Modified Delphi Process. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:14-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Choe JH, Overman MJ, Fournier KF, Royal RE, Ohinata A, Rafeeq S, Beaty K, Phillips JK, Wolff RA, Mansfield PF. Improved Survival with Anti-VEGF Therapy in the Treatment of Unresectable Appendiceal Epithelial Neoplasms. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2578-2584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Grotz TE, Mansfield PF, Royal RE, Mann GN, Rafeeq S, Beaty KA, Overman MJ, Fournier KF. Intrathoracic Chemoperfusion Decreases Recurrences in Patients with Full-Thickness Diaphragm Involvement with Mucinous Appendiceal Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2914-2919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Edge SB. American Joint Committee on Cancer., American Cancer Society. AJCC cancer staging handbook: from the AJCC cancer staging manual. New York: Springer 2010; . |

| 12. | Aaltonen LA, Hamilton SR. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon Oxford: IARC Press 2000; . |

| 13. | Overman MJ, Fournier K, Hu CY, Eng C, Taggart M, Royal R, Mansfield P, Chang GJ. Improving the AJCC/TNM staging for adenocarcinomas of the appendix: the prognostic impact of histological grade. Ann Surg. 2013;257:1072-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Davison JM, Choudry HA, Pingpank JF, Ahrendt SA, Holtzman MP, Zureikat AH, Zeh HJ, Ramalingam L, Zhu B, Nikiforova M. Clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of disseminated appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: identification of factors predicting survival and proposed criteria for a three-tiered assessment of tumor grade. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:1521-1539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sirintrapun SJ, Blackham AU, Russell G, Votanopoulos K, Stewart JH, Shen P, Levine EA, Geisinger KR, Bergman S. Significance of signet ring cells in high-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma of the peritoneum from appendiceal origin. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:1597-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chua TC, Moran BJ, Sugarbaker PH, Levine EA, Glehen O, Gilly FN, Baratti D, Deraco M, Elias D, Sardi A. Early- and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2449-2456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 658] [Cited by in RCA: 780] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Asare EA, Compton CC, Hanna NN, Kosinski LA, Washington MK, Kakar S, Weiser MR, Overman MJ. The impact of stage, grade, and mucinous histology on the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy in adenocarcinomas of the appendix: Analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2016;122:213-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Smeenk RM, Verwaal VJ, Antonini N, Zoetmulder FA. Survival analysis of pseudomyxoma peritonei patients treated by cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 2007;245:104-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |