Published online Mar 15, 2017. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v9.i3.121

Peer-review started: November 4, 2016

First decision: November 30, 2016

Revised: December 13, 2016

Accepted: January 2, 2017

Article in press: January 3, 2017

Published online: March 15, 2017

Processing time: 127 Days and 19.9 Hours

To characterize patients with gastric peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) and their typical clinical and treatment course with palliative systemic chemotherapy as the current standard of care.

We performed a retrospective electronic chart review of all patients with gastric adenocarcinoma with PC diagnosed at initial metastatic presentation between January 2010 and December 2014 in a single tertiary referral centre.

We studied a total of 271 patients with a median age of 63.8 years and median follow-up duration of 5.1 mo. The majority (n = 217, 80.1%) had the peritoneum as the only site of metastasis at initial presentation. Palliative systemic chemotherapy was eventually planned for 175 (64.6%) of our patients at initial presentation, of which 171 were initiated on it. Choice of first-line regime was in accordance with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for Gastric Cancer Treatment. These patients underwent a median of one line of chemotherapy, completing a median of six cycles in total. Chemotherapy disruption due to unplanned hospitalizations occurred in 114 (66.7%), while cessation of chemotherapy occurred in 157 (91.8%), with 42 cessations primarily attributable to PC-related complications. Patients who had initiation of systemic chemotherapy had a significantly better median overall survival than those who did not (10.9 mo vs 1.6 mo, P < 0.001). Of patients who had initiation of systemic chemotherapy, those who experienced any disruptions to chemotherapy due to unplanned hospitalizations had a significantly worse median overall survival compared to those who did not (8.7 mo vs 14.6 mo, P < 0.001).

Gastric PC carries a grim prognosis with a clinical course fraught with disease-related complications which may attenuate any survival benefit which palliative systemic chemotherapy may have to offer. As such, investigational use of regional therapies is warranted and required validation in patients with isolated PC to maximize their survival outcomes in the long run.

Core tip: We present a retrospective review of the clinical course and treatment outcomes of patients with gastric peritoneal carcinomatosis. It carries a poor prognosis with a clinical course fraught with disease-related complications which disrupts planned systemic palliative chemotherapy in the majority of patients. Such disruptions attenuate the benefits of systemic chemotherapy and decrease overall survival. Patients with isolated peritoneal disease may as such benefit from investigational loco-regional therapies pending further studies and validation.

- Citation: Tan HL, Chia CS, Tan GHC, Choo SP, Tai DWM, Chua CWL, Ng MCH, Soo KC, Teo MCC. Gastric peritoneal carcinomatosis - a retrospective review. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2017; 9(3): 121-128

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v9/i3/121.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v9.i3.121

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer across the world, accounting for 723000 deaths per year, the third most frequent cause of cancer-related deaths[1-3]. In Singapore, gastric cancer ranks as the seventh and ninth most common cancers, but accounts for the fourth and fifth most frequent cancer deaths amongst males and females respectively[4]. The poor prognosis of gastric cancer has in part been attributed to the high incidence of advanced disease at presentation, with up to 39% harboring disseminated disease at diagnosis[5]. Metastatic gastric cancer carries a grim prognosis with a median overall survival of approximately four months and five-year survival rates of 3%-6%[1,6,7]. Although palliative systemic chemotherapy has been demonstrated in numerous trials to improve survival amongst patients with metastatic gastric cancer to a median of 7.5-12.3 mo[8-11], whether such a benefit accrues equally to all sites of gastric cancer metastases is unclear.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) is recognized as an independent poor prognostic factor and is known to have a penchant for causing a wide range of troubling clinical symptoms including symptomatic ascites, intestinal obstruction, perforation and obstructive uropathy[12]. This can result in repeated hospitalizations, therapeutic interventions and rapid deterioration of a patient’s performance status, which may serve to interrupt and prematurely terminate any planned palliative systemic chemotherapy regime a patient might be on. There is a paucity of literature on the characteristics of patients with gastric PC[5], with virtually no studies examining the clinical and treatment course of these patients. The advent of studies examining the role of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for the treatment of gastric PC was borne from the concept of peritoneal metastases being a loco-regional disease extension rather than a true systemic dissemination of gastric cancer[13-18]. Should patients with gastric PC be less likely to complete planned courses of palliative systemic chemotherapy and hence perform relatively poorly, it would further bolster the case for studying CRS and HIPEC for a select group of patients with gastric PC to maximize their survival.

As such, we aim to characterize patients with gastric PC and their typical clinical and treatment course to glean a better understanding of how well this subset of metastatic gastric cancer patients are doing with palliative systemic chemotherapy as the current standard of care.

We performed a retrospective review of all patients with metastatic gastric cancer managed at the National Cancer Centre Singapore, the largest tertiary referral centre for cancer treatment locally, over a 5-year period between January 2010 and December 2014. All patients with gastric adenocarcinoma with peritoneal metastasis diagnosed at initial metastatic presentation, with or without other concomitant distant sites of metastasis, were included in our study. Patients with isolated positive peritoneal cytology were excluded. Electronic records were reviewed for various patient characteristics including patient demographics, gastric cancer characteristics, treatments administered and subsequent clinical course through each patient’s follow-up duration.

All patients included in the study had computed tomography scans of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis performed for initial staging following the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma. Patients without radiological evidence of metastatic disease then underwent staging laparoscopy with intra-operative frozen section assessment of peritoneal deposits.

Palliative systemic chemotherapy was offered as the standard of care in our institution to all patients with metastatic gastric cancer in close discussion with each patient. The first-line palliative systemic chemotherapy regime for each patient was chosen in accordance to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for Gastric Cancer Treatment with consideration to each patient’s performance status and preferences, favoring two to three-agent chemotherapy combinations over single-agent chemotherapy where possible[19]. Trastuzumab was additionally offered in cases which were positive for Her2/Neu overexpression. Chemotherapy regime was switched or discontinued based on clinician discretion during the course of follow-up if patients experienced unacceptable levels of toxicity or had clinical evidence of disease progression. Chemotherapy was also put on hold or stopped entirely in the event of acute deteriorations in patients’ functional and/or medical conditions. Other therapeutic interventions including surgery, endoscopic therapy and radiotherapy were also undertaken where clinically indicated. Follow-up duration of each patient is calculated in months beginning from initial diagnosis till the last follow-up or death at the point of data collection.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics Version 19.0 (Armonk NY: IBM Corp). Continuous and categorical variables and survival data were analyzed using the Student’s t-test, χ2 test and Kaplan-Meier analysis respectively, with a statistical significance level of 5% used.

We studied a total of 271 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma with PC diagnosed at initial metastatic presentation with a median follow-up duration of 5.1 mo (IQR: 2.2-11.7). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 63.8 years (range 26.9-89.0), with relatively equal gender proportions (49.4% male) and a predominant Chinese ethnicity (74.9%). The majority of patients had good functional and medical conditions at the point of diagnosis, with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ratings of 0-1 in 82.6% and American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) scores of 1-2 in 86.7%.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Median age (range) (yr) | 63.8 (26.9-89.0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Chinese | 203 (74.9) |

| Indian | 13 (4.8) |

| Malay | 20 (7.4) |

| Others | 35 (12.9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 134 (49.4) |

| Female | 137 (50.6) |

| ECOG status | |

| 0 | 89 (32.8) |

| 1 | 135 (49.8) |

| 2 | 28 (10.3) |

| 3 | 11 (4.1) |

| 4 | 8 (3.0) |

| ASA score | |

| 1 | 107 (39.5) |

| 2 | 128 (47.2) |

| 3 | 36 (13.3) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 56 (20.7) |

| Hypertension | 124 (45.8) |

| Cardiac comorbidities | 43 (15.9) |

| Respiratory comorbidities | 15 (5.5) |

| Chronic renal impairment | 10 (3.7) |

| Central nervous system comorbidity | 19 (7.0) |

| Previous cancer | 27 (10.0) |

| Cigarette smoking | 58 (21.4) |

| Regular alcohol use | 31 (11.4) |

The bulk of our patients (n = 258, 95.2%) had peritoneal metastasis diagnosed at initial gastric cancer diagnosis, while the remaining 13 (4.8%) cases of PC were diagnosed as a metastatic recurrence of previously treated gastric cancer. In our cohort, 217 (80.1%) patients had the peritoneum as the only site of metastasis at initial presentation, while 54 (19.9%) had other concomitant distant site(s) of metastasis. Approximately half of the diagnosis of PC was made radiologically (n = 134, 49.4%) while the remainder was made intra-operatively. Other gastric cancer-related characteristics of our cohort are summarized in Table 2. Of note, when comparing patients with peritoneal metastasis only to patients with other concomitant distant sites of metastasis, there was a higher proportion of females (53.9% vs 37.0%, P = 0.026) and diffuse histology (57.1% vs 33.3%, P = 0.002), and a lower proportion of HER2/Neu overexpression (16.4% vs 33.3%, P = 0.029).

| Characteristic (n = 271) | n (%) |

| Presentation of peritoneal metastases | |

| At initial gastric cancer diagnosis | 258 (95.2) |

| Recurrence of treated gastric cancer | 13 (4.8) |

| Site of metastases | |

| Peritoneal only | 217 (80.1) |

| Peritoneal and distant site(s) | 54 (19.9) |

| Primary gastric cancer location | |

| Gastroesophageal junction | 23 (8.5) |

| Proximal gastric | 16 (5.9) |

| Gastric body | 101 (37.3) |

| Distal gastric | 103 (38.0) |

| Linitis plastica | 28 (10.3) |

| Lauren’s classification | |

| Intestinal | 129 (47.6) |

| Diffuse | 142 (52.4) |

| c-erb-B2 receptor status (n = 195) | |

| Positive | 37 (19.0) |

| Negative | 158 (81.0) |

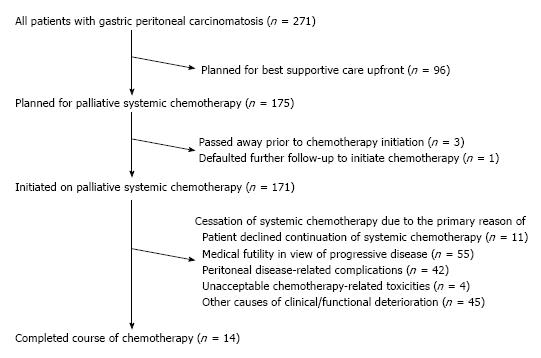

Palliative systemic chemotherapy was offered as standard of care in all patients with metastatic gastric cancer in our institution in close discussion with each patient, with 175 (64.6%) patients eventually planned for systemic chemotherapy following initial metastatic presentation. The subsequent chemotherapy-related clinical course of these patients is summarized in Figure 1. Expectedly, the baseline functional and medical status of patients planned for systemic chemotherapy were significantly better than those who opted for best supportive care upfront, with ECOG ratings 0-2 in 98.9% vs 82.3% (P < 0.001) and ASA scores of 1-2 in 92.0% vs 77.1% (P = 0.001). Four patients planned for systemic chemotherapy did not eventually initiate chemotherapy as three passed away prior to chemotherapy initiation due to cancer-related complications while one defaulted further follow-up for chemotherapy initiation.

The most common first-line chemotherapy regimes utilized in our cohort are summarized in Table 3. Notably, of the 171 patients who eventually initiated chemotherapy, 138 (80.7%) patients received two or three-agent chemotherapy regimes as first-line therapy. Our patients underwent a median of one line of chemotherapy (IQR 1-2), completing a median of six cycles in total (IQR 3-11). Chemotherapy was disrupted in 114 (66.7%) cases due to unplanned hospitalizations, with a median duration of disruption of two weeks (IQR 1-2.25) each time. Chemotherapy-related toxicity was documented in 81 (47.4%) of cases, most commonly affecting the gastrointestinal (n = 28, 34.6%), neurological (n = 23, 28.4%) and hematological (n = 22, 27.2%) systems.

| Chemotherapy regime (n = 171) | n (%) |

| Anthracycline + platinum-based agent + nucleotide analogue Examples epirubicin + cisplatin + 5-fluorouracil epirubicin + oxaliplatin + 5-fluorouracil | 13 (7.6) |

| Platinum-based agent + nucleotide analogue Examples cisplatin + 5-fluorouracil oxaliplatin + capecitabine cisplatin + S-1 | 97 (56.7) |

| Nucleotide analogue monotherapy Examples 5-fluorouracil capecitabine S-1 | 30 (17.5) |

| FOLFOX (5-fluorouracil + leucovorin + oxaliplatin) | 24 (14.0) |

| Other regimes (e.g., Docetaxel + cisplatin + 5-fluorouracil) | 7 (4.2) |

Cessation of systemic chemotherapy occurred in 157 (91.8%) of patients due to a variety of reasons as delineated in Figure 1. Of note, slightly over a quarter (n = 42, 26.8%) of cessations were primarily attributable to peritoneal disease-related complications. Eventually, only 14 (8.2%) patients completed their courses of chemotherapy with subsequent close clinical surveillance.

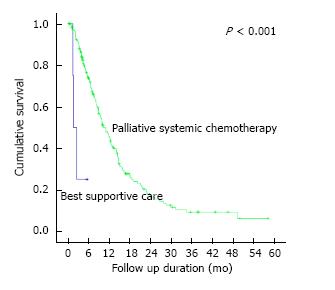

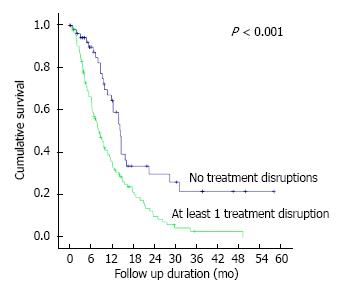

Through the course of follow-up, 201 (74.2%) patients required unplanned hospitalizations (median number of hospitalizations = 2, IQR 1-3) following initial diagnosis for various disease and/or treatment-related complications including symptomatic ascites, sepsis, gastric outlet obstruction and gastrointestinal tract bleeding (Table 4). 242 (89.3%) patients required some form of therapeutic intervention in an outpatient and/or inpatient setting including surgery, endoscopic stenting, feeding tube insertion and radiotherapy (Table 5). Median overall survival of our patient cohort was 8.7 mo (95%CI: 7.3-10.1) with a trend towards longer survival amongst patients with peritoneal metastasis only as compared to those with other concomitant distant sites of metastasis (median survival 8.9 mo vs 7.0 mo, P = 0.061). The 171 patients who initiated systemic chemotherapy, when compared to the rest of the patients who received best supportive care upfront, had a significantly better median overall survival of 10.9 mo vs 1.6 mo (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). Of these patients who initiated systemic chemotherapy, the ones who experienced any disruptions to chemotherapy due to unplanned hospitalizations had a significantly worse median survival compared to those without chemotherapy disruptions (8.7 mo vs 14.6 mo, P < 0.001) (Figure 3).

| Reason (n = 201) | n (%) |

| Symptomatic ascites | 64 (31.8) |

| Sepsis | 64 (31.8) |

| Gastric outlet obstruction | 60 (29.9) |

| Bleeding GIT | 60 (29.9) |

| Intestinal obstruction | 59 (29.4) |

| Chemotherapy-related toxicity | 23 (11.4) |

| Obstructive jaundice | 17 (8.5) |

| Obstructive uropathy | 17 (8.5) |

| Tumour perforation | 7 (3.5) |

| Treatment category | Treatment | n (%) |

| Surgery | Palliative gastrectomy | 32 (36.0) |

| n = 89 (32.8%) | Surgical bypass | 46 (51.7) |

| Open gastrostomy | 2 (2.2) | |

| Feeding jejunostomy | 5 (5.6) | |

| Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy | 1 (1.1) | |

| Others | 3 (3.3) | |

| Endoscopic intervention | Feeding tube insertion only | 45 (78.9) |

| n = 57 (21.0%) | Stenting only | 8 (14.0) |

| Feeding tube insertion and stenting | 4 (7.0) | |

| Radiotherapy | Radiotherapy to gastric tumour | 29 (82.9) |

| n = 35 (12.9%) | Radiotherapy to other sites | 6 (17.1) |

Existing literature on gastric cancer has largely evaluated metastatic gastric cancer as a homogeneous, undifferentiated entity, with clinical features, prognostic factors, treatment outcomes and overall survival examined as a single patient group[1-3]. In a similar vein, treatment for metastatic gastric cancer has also been predominated by palliative systemic chemotherapy and supportive care[20]. There has been a growing interest in the treatment of PC with the advent of CRS and HIPEC especially in colorectal and appendiceal malignancies. The idea of peritoneal metastasis representing loco-regional disease extension as opposed to systemic dissemination in other sites of metastasis has likewise encouraged ventures at examining the benefit of CRS and HIPEC in the treatment of PC of other primaries, including gastric cancer[21]. Our understanding of the clinical characteristics of this subgroup of metastatic gastric cancer patients with PC and how they fare with the current gold standard of treatment - palliative systemic chemotherapy - remains limited, a knowledge gap we sought to address through this study.

Gastric PC was reported by Thomassen et al[5] to account for a sizeable 35.0% of metastatic disease at presentation, with PC as the only site of metastasis in 68.6% of cases, comparable to 80.1% of cases in our cohort. It similarly represents 36.0%-45.9% of metastatic recurrences after previous curative treatment for gastric cancer[22,23]. Several studies have reported clinical characteristics predictive of peritoneal metastasis at presentation or recurrence including a younger age, female gender, serosal involvement of primary tumor and a diffuse histology. We found the female gender, diffuse histology and absence of HER2/Neu overexpression to be associated with PC as the sole site of metastatic disease in gastric cancer[5,23].

Palliative systemic chemotherapy has been well established as the current standard of care for patients with metastatic gastric cancer. A recent meta-analysis of 35 trials involving 5726 patients demonstrated that, in terms of overall survival, systemic chemotherapy achieves superior outcomes compared to best supportive care, and that combination chemotherapy is superior to single-agent chemotherapy with the trade-off of increased incidence of chemotherapy-related toxicity[20].

Despite the fact that the subgroup of our patient cohort planned for systemic chemotherapy had highly optimal baseline functional and medical statuses (98.9% with ECOG ratings of 0-2 and 92.0% with ASA scores of 1-2) with a large proportion (80.7%) undergoing two to three-agent combination chemotherapy regimes upfront, only a mere 14 (8.2%) patients eventually completed their chemotherapy regimes with subsequent close clinical surveillance. This could be attributed to several reasons.

Firstly, a significant proportion of patients who initiated chemotherapy had clinical evidence of progressive disease in spite of treatment, and even after a trial of second, third or fourth-line regimes in a handful of patients, 32.2% eventually opted for supportive care in view of treatment futility. The poor response of PC to conventional systemic chemotherapy could in part be accounted for by the poor penetration of peritoneal deposits by chemotherapeutic agents administered systemically[24]. This has spurred efforts at studying the efficacy of a combined bidirectional intravenous and intraperitoneal route of chemotherapy administration for PC, which has been proven to confer survival benefit in ovarian cancer, and has been tested in several phase 2 trials for gastric PC with encouraging results[25,26].

Secondly, a large proportion of our cohort (74.2%) required unplanned hospitalizations due to disease and/or treatment-related complications, each of which could significantly accelerate the process of clinical deterioration. The median number of hospitalizations each of these patients required was 2, for a variety of complications including those attributable to PC including symptomatic ascites, bowel obstruction, obstructive uropathy and obstructive jaundice. Besides resulting in unforeseen breaks in systemic chemotherapy occurring in 66.7% of our patients who underwent chemotherapy, these acute clinical events also directly contributed to significant clinical and functional decline necessitating premature cessation of chemotherapy in a quarter of cases (Figure 1). Considering that a sizeable proportion of patients who ceased chemotherapy due to other causes of clinical/functional deterioration were attributable to nosocomial infections contracted during admissions for peritoneal disease-related complications, the inadvertent impact of PC on cessation of systemic chemotherapy in these patients may indeed be even greater. The consequent impact on survival outcomes is evident from our finding of a significantly worse overall survival amongst patients on systemic chemotherapy who experienced treatment disruptions (Figure 3).

We report an overall survival of 8.7 mo in our cohort, comparable to survival outcomes of 7.5-12.3 mo achieved by patients on systemic chemotherapy in several trials[8-11]. Stratified analysis revealed a trend towards improved survival in patients with isolated peritoneal metastasis, in keeping with findings of Thomassen et al[5] which reported median survival of 4.6 and 3.3 mo in patients with isolated peritoneal metastasis and peritoneal plus other concomitant distant sites of metastasis respectively. This is consistent with proposed theories of isolated PC as a loco-regional disease extension rather than a true systemic dissemination of metastatic disease, which further lends support to the investigational use of aggressive loco-regional treatment with CRS and HIPEC in at least selected cases to maximize survival outcomes.

While we recognize the limitations inherent to the retrospective nature of our study, it is, to the best of our knowledge, the only study after Thomassen et al[5] to examine the demographic and disease characteristics of gastric PC, and the first study to examine the clinical and treatment course of these patients.

Looking ahead, further studies could examine and compare the clinical course and outcomes of gastric cancer patients with different groups of metastatic sites (e.g., peritoneal metastasis vs isolated liver metastasis vs other distant sites of metastasis). Additionally, delving further into gastric PC, further work could be put into determining if the extent of peritoneal involvement affects clinical course and outcomes, which could in turn help better define a patient subgroup which may best benefit from aggressive loco-regional treatment options.

Gastric PC carries a grim prognosis with a clinical course fraught with disease-related complications which may attenuate any survival benefit palliative systemic chemotherapy has to offer. As such, investigational use of regional therapies is warranted and required validation in patients with isolated PC to maximize their survival outcomes in the long run.

Systemic palliative chemotherapy is the current standard of care for all metastatic gastric cancers, including cases with peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC). Gastric PC is known to cause symptoms requiring repeated hospitalizations which may interrupt and terminate planned palliative systemic chemotherapy. There exists a paucity of literature examining the clinical course of patients with gastric PC. The authors aimed to characterize patients with gastric PC and their typical clinical and treatment course with palliative systemic chemotherapy as the current standard of care.

While systemic palliative chemotherapy has been established as the standard of care through several randomized controlled trials demonstrating survival benefit, the overall prognosis of metastatic gastric cancer remains poor. Investigational loco-regional treatment options such as intraperitoneal chemotherapy and cytoreductive surgery are currently being studied and validated as alternative treatment of patients with gastric PC.

This is, to the best of the knowledge, the only study after Thomassen et al to examine the demographic and disease characteristics of gastric PC, and the first study to examine the clinical and treatment course of these patients.

The authors demonstrated that patients with gastric PC have a grim prognosis, with frequent disease-related complications requiring unplanned hospitalizations which disrupt and terminate planned palliative systemic chemotherapy. As such, patients with gastric PC may benefit from investigational loco-regional treatment options as an alternative.

The authors present a retrospective study of a cohort of patients with gastric cancer and peritoneal metastases treated in a single oncology center. The rationale for the study is important as the prognosis remains poor in this group of patients. The study derives a lot of clinical data describing patients’ baseline characteristics and their course during palliative therapy. The results are consistent with those presented in previous studies.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Singapore

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chrom P, Fujita T, Ilson DH S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Arndt V. Epidemiology of stomach cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:467-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2137-2150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2591] [Cited by in RCA: 2646] [Article Influence: 139.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stomach Cancer Estimated Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. [accessed 2016 Dec 1]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/old/FactSheets/cancers/stomach-new.asp. |

| 4. | Lee HP. Trends in Cancer Incidence in Singapore 2010-2014. Singapore Cancer Registry. [published 2015 May 26]. Available from: https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/default-document-library/cancer-trends-2010-2014_interim-annual-report_final-(public).pdf?sfvrsn=0. |

| 5. | Thomassen I, van Gestel YR, van Ramshorst B, Luyer MD, Bosscha K, Nienhuijs SW, Lemmens VE, de Hingh IH. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of gastric origin: a population-based study on incidence, survival and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:622-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yang D, Hendifar A, Lenz C, Togawa K, Lenz F, Lurje G, Pohl A, Winder T, Ning Y, Groshen S. Survival of metastatic gastric cancer: Significance of age, sex and race/ethnicity. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;2:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Liu X, Cai H, Sheng W, Wang Y. Long-term results and prognostic factors of gastric cancer patients with microscopic peritoneal carcinomatosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Murad AM, Santiago FF, Petroianu A, Rocha PR, Rodrigues MA, Rausch M. Modified therapy with 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and methotrexate in advanced gastric cancer. Cancer. 1993;72:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pyrhönen S, Kuitunen T, Nyandoto P, Kouri M. Randomised comparison of fluorouracil, epidoxorubicin and methotrexate (FEMTX) plus supportive care with supportive care alone in patients with non-resectable gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:587-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 571] [Cited by in RCA: 579] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Scheithauer W. Palliative chemotherapy versus supportive care in patients with metastatic gastric cancer: a randomized trial. Second International Conference on Biology, Prevention and Treatment of GI Malignancy, Koln. 1995;68 (abstract). |

| 11. | Glimelius B, Ekström K, Hoffman K, Graf W, Sjödén PO, Haglund U, Svensson C, Enander LK, Linné T, Sellström H. Randomized comparison between chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care in advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:163-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sangisetty SL, Miner TJ. Malignant ascites: A review of prognostic factors, pathophysiology and therapeutic measures. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;4:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Gill RS, Al-Adra DP, Nagendran J, Campbell S, Shi X, Haase E, Schiller D. Treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC: a systematic review of survival, mortality, and morbidity. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:692-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fujimoto S, Takahashi M, Mutou T, Kobayashi K, Toyosawa T, Isawa E, Sumida M, Ohkubo H. Improved mortality rate of gastric carcinoma patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemoperfusion combined with surgery. Cancer. 1997;79:884-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yonemura Y, Fujimura T, Nishimura G, FallaR T, Katayama K, Tsugawa K, Fushida S, Miyazaki I, Tanaka M, Endou Y. Effects of intraoperative chemohyperthermia in patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Surgery. 1996;119:437-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rossi CR, Pilati P, Mocellin S, Foletto M, Ori C, Innocente F, Nitti D, Lise M. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal intraoperative chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis arising from gastric adenocarcinoma. Suppl Tumori. 2003;2:S54-S57. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Glehen O, Schreiber V, Cotte E, Sayag-Beaujard AC, Osinsky D, Freyer G, François Y, Vignal J, Gilly FN. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia for peritoneal carcinomatosis arising from gastric cancer. Arch Surg. 2004;139:20-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yonemura Y, Endou Y, Shinbo M, Sasaki T, Hirano M, Mizumoto A, Matsuda T, Takao N, Ichinose M, Mizuno M. Safety and efficacy of bidirectional chemotherapy for treatment of patients with peritoneal dissemination from gastric cancer: Selection for cytoreductive surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:311-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Gastric Cancer Version 3.2015. [accessed 2016 Mar 27]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf. |

| 20. | Wagner AD, Unverzagt S, Grothe W, Kleber G, Grothey A, Haerting J, Fleig WE. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD004064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yan TD, Black D, Sugarbaker PH, Zhu J, Yonemura Y, Petrou G, Morris DL. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials on adjuvant intraperitoneal chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2702-2713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Roviello F, Marrelli D, de Manzoni G, Morgagni P, Di Leo A, Saragoni L, De Stefano A. Prospective study of peritoneal recurrence after curative surgery for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1113-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yoo CH, Noh SH, Shin DW, Choi SH, Min JS. Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2000;87:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 555] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schneider JG. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1994;21:195-212. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Yamaguchi H, Kitayama J, Ishigami H, Emoto S, Yamashita H, Watanabe T. A phase 2 trial of intravenous and intraperitoneal paclitaxel combined with S-1 for treatment of gastric cancer with macroscopic peritoneal metastasis. Cancer. 2013;119:3354-3358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ishigami H, Kitayama J, Kaisaki S, Hidemura A, Kato M, Otani K, Kamei T, Soma D, Miyato H, Yamashita H. Phase II study of weekly intravenous and intraperitoneal paclitaxel combined with S-1 for advanced gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |