Published online Mar 15, 2016. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i3.321

Peer-review started: October 4, 2015

First decision: November 5, 2015

Revised: December 11, 2015

Accepted: December 19, 2015

Article in press: December 21, 2015

Published online: March 15, 2016

Processing time: 156 Days and 12 Hours

Myeloid sarcoma, also known as granulocytic sarcoma or chloroma is an unusual accumulation of malignant myeloid precursor cells in an extramedullary site, which disrupts the normal architecture of the involved tissue. It is known to occur more commonly in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia and less commonly in those with myelodysplastic syndrome and myeloproliferative neoplasm, such as chronic myelogenous leukemia. The most common sites of involvement include bone, skin and lymph nodes. However, rare cases have been reported in the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, or breast. Most commonly, a neoplastic extramedullary proliferation of myeloid precursors in a patient would have systemic involvement of a myeloid neoplasm, including in the bone marrow and peripheral blood. Infrequently, extramedullary disease may be the only site of involvement. It may also occur as a localized antecedent to more generalized disease or as a site of recurrence. Herein, we present the first case in the English literature of a patient presenting with an isolated site of myeloid sarcoma arising in the form of a colonic polyp which, after subsequent bone marrow biopsy, was found to be a harbinger of chronic myelogenous leukemia.

Core tip: Myeloid sarcoma rarely presents in the gastrointestinal tract. Rarer still, does myeloid sarcoma manifest in the gastrointestinal tract without systemic involvement by a myeloid neoplasm. This case report documents the first instance in the English literature wherein an isolated extramedullary site of myeloid sarcoma adopting the form of a colonic polyp was found to be a harbinger of chronic myelogenous leukemia.

- Citation: Rogers R, Ettel M, Cho M, Chan A, Wu XJ, Neto AG. Myeloid sarcoma presenting as a colon polyp and harbinger of chronic myelogenous leukemia. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2016; 8(3): 321-325

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v8/i3/321.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v8.i3.321

Myeloid sarcoma (MS) is defined as an extramedullary tumor composed of myeloid precursors which efface the normal architecture of the involved tissue[1-3]. There is a predilection for males and the median age at diagnosis is 56 years[1-3]. MS occurring de novo is considered the equivalent of a diagnosis of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML)[1-3]. It may precede or coincide with AML, signify a relapse in AML or constitute an acute blastic transformation of myelodysplastic syndrome or myeloproliferative neoplasms, such as chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) (663, 742)[1-3]. In this case report, we illustrate a novel presentation of this lesion, discuss its histologic appearance and hematopathologic workup, and review the pertinent literature.

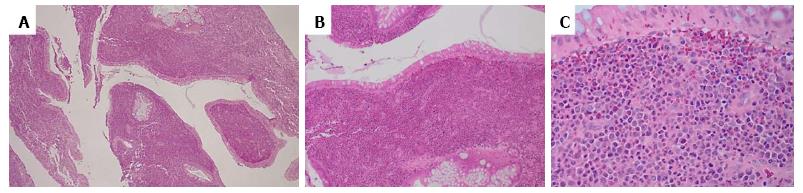

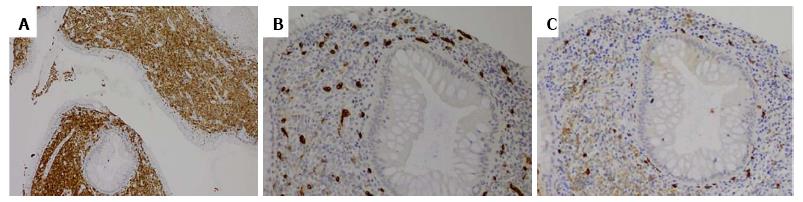

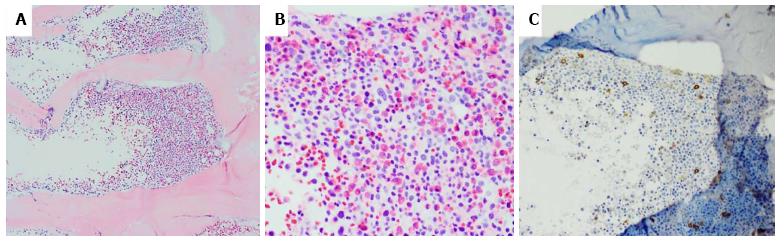

A 55-year-old man with hematochezia for an unknown period of time underwent colonoscopy. A polyp (< 1 cm) was seen in the colon, 20 cm from the anal verge, and was retrieved. No other endoscopic findings were identified. HE slides and accompanying immunostained slides from the colon polyp were evaluated at our institution after referral from the outside institution. HE sections showed polypoid colonic mucosa markedly expanded by an infiltrate of sheets of large neoplastic cells exhibiting fine chromatin, prominent nucleoli and moderately irregular nuclear contour (Figure 1). The background stroma was expanded by a mixed cellular infiltrate. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the large, immature appearing neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for myeloproxidase, lysozyme, CD43, CD15, and CD33 (Figure 2), while negative for B-cell markers (CD20, CD79a, Pax5), T/NK-cell markers (CD3, CD56, granzyme), and plasma cell marker (CD138). Few scattered neoplastic cells were positive for CD34 and CD117 (Figure 2). In addition, the neoplastic cells were negative for CD30, CD61 and glycophorin. The findings support the diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma (MS). The neoplastic cells were limited to the polyp with adjacent fragments of colonic mucosa in the biopsy showing unremarkable findings. During subsequent workup, the patient was noted to have a leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 221 k/μL, Hgb 11.7 g/dL, MCV 89.1 fL, and platelets 366 k/μL. The bone marrow biopsy showed hypercellular marrow with myeloid hyperplasia (Figure 3). There was no evidence of increased blasts (Figure 3). Cytogenetics reported a t(9;22) translocation in the bone marrow. A diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia, Ph+ was rendered. A retrospective FISH analysis for t(9;22) performed on the colonic polyp was negative. Because Ph chromosome + CML with MS in the colon is considered equivalent to a blast crisis, the patient received systemic chemotherapy, with protein kinase inhibitors (PKIs) and Dasatinib. Repeat colonoscopies two and three years later showed no residual or recurrent disease. Follow up bone marrow biopsies over a five-year period demonstrated a cytogenetic and morphologic complete response with minimal residual CML by molecular analysis. A bone marrow biopsy in 2014 showed that the number of cells carrying the t(9;22) translocation had risen from < 1% previously to 13%. The most recent bone marrow biopsy in March 2015 was stable with the prior biopsy. The patient did not receive bone marrow transplantation.

MS has been referred to as chloroma because of the green hue imparted to the cut surface of the tumor due to the presence of myeloperoxidase, an enzyme present in granulocytic cells. MS is known to occur in patients with various myeloid neoplasms. It occurs predominantly in four clinicopathological situations: (1) as a harbinger of AML in the non-leukemic patient; (2) as a sign of impending blast crisis in CML or leukemic transformation in myelodysplastic disorders; (3) as an additional manifestation in patients with known AML; and (4) as an isolated event, preceding the onset in the marrow by months to years[4-9].

Our case showed an unusual presentation of hematochezia resulting from an isolated colonic polyp which subsequently revealed Ph+ CML upon workup. This unexpected diagnosis of MS, an AML equivalent, prompted the systemic chemotherapy and evaluation for potential bone marrow transplant as a future therapy modality. Recognition of MS is clinically critical for the choice of treatment modality. However, the majority of MS do not produce clinical signs and symptoms, hence the difficulty in making the diagnosis either clinically or histologically; it is most often discovered at autopsy[4]. Soft tissue, bone/spine, skin, lymph nodes and the periosteum are the commonest sites of involvement. MS infrequently involves the gastrointestinal tract[7-12]. Neiman et al[13] reported 61 such tumors and found gastrointestinal involvement in only 4 (7%) of the tumors[3]. Choi et al[7] reported 8 cases where the small bowel and large intestine were affected. It has been reported that the ileum is the most affected area in the intestine[14]. Isolated primary involvement of the colon and rectum is exceedingly rare with secondary extension from the peritoneum being more common[7]. Several reported cases of MS presented as an intraluminal polypoid mass, diffuse polyposis[7], or rarely, coexisting with adenoma[12]. Our case is one of the few cases that presented as polyp in the large intestine without any other manifestation of a leukemic process and the first case to reveal Ph+ CML upon subsequent workup.

When present in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in the intestine, the most common complication of leukemic involvement is massive hemorrhage, perforation, necrosis, acute or intermittent abdominal pain from partial to complete bowel obstruction and intussusceptions[4,15,16]. Nevertheless, MS of the gastrointestinal tract can be also an isolated manifestation in the absence of any hematologic disorder, thereby precluding an overt diagnosis of MS[4,7,9,17,18]. The diagnosis of MS can be challenging and confused with other malignant tumors by histomorphologic evaluation. The morphologic features of the tumors can be poorly differentiated or that of nondistinct hematolymphoid neoplasms with little or no evidence of myeloid differentiation by morphology. To that end, a significant proportion of tumors (47%-56%) are initially misdiagnosed as malignant lymphoproliferative disorders including Hodgkin lymphoma, lymphoblastic lymphoma,Burkitt’s lymphoma, large cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, small round blue cell tumors (Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma), or poorly differentiated carcinoma[14,19]. An accurate diagnosis of MS is of great clinical importance in the ongoing management of hematologic malignancies, and must be distinguished from extranodal lymphoma and other entities aforementioned, in order to achieve optimal therapeutic benefit and avoid detrimental outcome[12,19]. If left untreated, the majority (88%) of MS patients progress to AML within 11 mo whereas a much longer disease free interval is noted in patients receiving upfront treatment with AML chemotherapy[12]. Of note, patients with isolated MS of the GI tract who are treated with standard induction chemotherapy appear to have a substantially lower probability of subsequent development of leukemic form of AML[7,20].

The current World Health Organization classification system states that MS most commonly consists of myeloblasts with or without maturation that partially or totally efface the tissue architecture in an extramedullary site[1]. Tumors with other hematopoietic elements such as erythroid precursors or megakaryocytes are rare and may occur in conjunction with transformation of myeloproliferative neoplasms[1,3]. In a significant proportion of cases, MS displays myelomonocytic or pure monoblastic phenotypes[1-3]. The common cytogenetics abnormalities include trisomy 8, t(8;21), inv(16), and rearrangement involving MLL[1]. Of note, it bears mentioning that extramedullary hematopoietic tumor (EMT) is not considered the same tumor, has a different prognosis, warrants different treatment strategy and is not covered here.

In our patient with Ph+ CML, myeloid sarcoma in the colon polyp failed to demonstrate the presence of t(9;22) translocation by FISH analysis. There have been reported cases of development of clonal unrelated AML or myeloid sarcoma in CML patients. These patients usually had a prolonged history of CML with interferon and busulphan treatment or tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment[21,22], which was not the case with our patient. The possibility of a false negative result exists with FISH analysis. However, given the limited material, further confirmatory testing by cytogenetic analysis or molecular sequencing studies could not be performed.

As a general rule, systemic chemotherapy is recommended, given that MS has a dismal prognosis with a median survival of 9 mo from the time of diagnosis[23,24]. Because most cases of MS progress to AML, the majority of investigators recommend the treatment for AML[4,7,25]. Most of the tumors respond to chemotherapy or external radiation. Patients with MS should also be considered as high risk AML with a poor outcome and an early and intensive therapy according to AML protocols, possibly including allogenic/autologous bone marrow transplantation in the first remission, is strongly suggested in order to avoid systemic involvement which could occur with the use of only local surgical or radiation therapies[4,26]. The clinical behavior and response to therapy seem not to be influenced by any of the following factors: Age, sex, anatomical site(s) involved, de novo presentation, histological features, immunophenotype, cytogenetic findings or clinical history related to AML, myelodysplastic syndrome, and myeloproliferative neoplasms[1,3]. Patients who undergo allogenic or autologous bone marrow transplantation seem to have a higher probability of prolonged survival or cure[1,3,27]. Our patient is still living at the time of this report, six years from his initial presentation.

In summary, MS presenting as a colonic polyp is infrequent. We describe an unusual presentation and emphasize the need to be aware of granulocytic sarcomas presenting in the GI tract, as they may precede or occur concurrently with acute myeloid leukemia, or reveal blastic transformation of chronic myeloproliferative disorders or myelodysplastic syndromes. MS can be easily misdiagnosed in this site, especially without a previous history of such disease. Indeed, experienced pathologists encounter difficulty with this lesion as incorrect initial diagnosis occurs in up to 50% of cases, most of which are diagnosed as high grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Therefore careful evaluation of morphology for evidence of myeloid differentiation, use of an immunohistochemistry panel, and high index of suspicion when confronted with a less differentiated neoplasm are required to avoid diagnostic pitfalls. Awareness and prompt recognition of this disease entity is of great clinical importance given that an early start of anti-leukemic therapy could lead to a longer survival for these patients. The prognosis is in general poor and comparable to that of other acute leukemias[4].

A 55-year-old man with no significant medical history presented with hematochezia.

Colonoscopy revealed a subcentimeter colon polyp located 20 cm from the anal verge.

Hyperplastic polyp, adenomatous polyp, malignant polyp.

White blood cell count was elevated (221 k/μL).

Myeloid sarcoma forming a colon polyp with subsequent cytogenetic studies of a bone marrow biopsy revealing chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

The patient received systemic chemotherapy including protein kinase inhibitors and a tyrosine inhibitor, Dasatinib.

There are infrequent reports of isolated primary involvement of the colon and rectum by myeloid sarcoma. This case is one of a few documented instances of myeloid sarcoma presenting as a colon polyp without any manifestations of a leukemic process and the first to reveal Ph+ CML upon subsequent workup.

Myeloid sarcoma is an extramedullary tumor composed of myeloid blasts with or without maturation which effaces the normal architecture of the involved tissue.

This case report serves to illustrate a unique manifestation of myeloid sarcoma. CML with myeloid sarcoma is considered equivalent to a blast crisis, and should be treated accordingly.

The paper is well-written. This is an interesting case.

P- Reviewer: Arasaradnam RP, Shehata MMM S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Pileri SA, Orazi A, Falini B. Myeloid Sarcoma. WHO Classification Of Tumours Of Haematopoietic And Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press 2008; 140-141. |

| 2. | Falini B, Lenze D, Hasserjian R, Coupland S, Jaehne D, Soupir C, Liso A, Martelli MP, Bolli N, Bacci F. Cytoplasmic mutated nucleophosmin (NPM) defines the molecular status of a significant fraction of myeloid sarcomas. Leukemia. 2007;21:1566-1570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pileri SA, Ascani S, Cox MC, Campidelli C, Bacci F, Piccioli M, Piccaluga PP, Agostinelli C, Asioli S, Novero D. Myeloid sarcoma: clinico-pathologic, phenotypic and cytogenetic analysis of 92 adult patients. Leukemia. 2007;21:340-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 518] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sevinc A, Aydogdu I. Extramedullary myeloid leukemia mimicking lepromatous leprosy. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1036-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Krause JR. Granulocytic sarcoma preceding acute leukemia: a report of six cases. Cancer. 1979;44:1017-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Meis JM, Butler JJ, Osborne BM, Manning JT. Granulocytic sarcoma in nonleukemic patients. Cancer. 1986;58:2697-2709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Choi ER, Ko YH, Kim SJ, Jang JH, Kim K, Kang WK, Jung CW, Kim DH. Gastric recurrence of extramedullary granulocytic sarcoma after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e54-e55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Singhal S, Powles R, Kulkarni S, Treleaven J, Saso R, Mehta J. Long-term follow-up of relapsed acute leukemia treated with immunotherapy after allogeneic transplantation: the inseparability of graft-versus-host disease and graft-versus-leukemia, and the problem of extramedullary relapse. Leuk Lymphoma. 1999;32:505-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chong G, Byrnes G, Szer J, Grigg A. Extramedullary relapse after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for haematological malignancy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:1011-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kaddu S, Beham-Schmid C, Zenahlik P, Kerl H, Cerroni L. CD56+ blastic transformation of chronic myeloid leukemia involving the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:497-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kuwabara H, Nagai M, Yamaoka G, Ohnishi H, Kawakami K. Specific skin manifestations in CD56 positive acute myeloid leukemia. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gorczyca W, Weisberger J, Seiter K. Colonic adenomas with extramedullary myeloid tumor (granulocytic sarcoma). Leuk Lymphoma. 1999;34:621-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Neiman RS, Barcos M, Berard C, Bonner H, Mann R, Rydell RE, Bennett JM. Granulocytic sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 61 biopsied cases. Cancer. 1981;48:1426-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ghafoor T, Zaidi A, Al Nassir I. Granulocytic sarcoma of the small intestine: an unusual presentation of acute myelogenous leukaemia. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60:133-135. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Steinberg J, Brandt LJ, Brenner S, Mahadevia P. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia with infiltration of the colon. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:1002-1004. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kohl SK, Aoun P. Granulocytic sarcoma of the small intestine. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1570-1574. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Byrd JC, Edenfield WJ, Dow NS, Aylesworth C, Dawson N. Extramedullary myeloid cell tumors in myelodysplastic-syndromes: not a true indication of impending acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;21:153-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee KH, Lee JH, Choi SJ, Lee JH, Kim S, Seol M, Lee YS, Kim WK, Seo EJ, Park CJ. Bone marrow vs extramedullary relapse of acute leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: risk factors and clinical course. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:835-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Toki H, Okabe K, Kimura Y, Kiura K, Shibata H, Hara K, Moriwaki S, Nanbu T, Iwashita A. Granulocytic sarcoma of the intestine as a primary manifestation nine months prior to overt acute myelogenous leukemia. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1987;17:79-85. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Au WY, Kwong YL, Lie AK, Ma SK, Liang R. Extra-medullary relapse of leukemia following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Hematol Oncol. 1999;17:45-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Manley R, Cochrane J, McDonald M, Rigby S, Moore A, Kirk A, Clarke S, Crossen PE, Morris CM, Patton WN. Clonally unrelated BCR-ABL-negative acute myeloblastic leukemia masquerading as blast crisis after busulphan and interferon therapy for BCR-ABL-positive chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1999;13:126-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Perrotti D, Jamieson C, Goldman J, Skorski T. Chronic myeloid leukemia: mechanisms of blastic transformation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2254-2264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Park FD, Bain AJ, Mittal RK. Granulocytic sarcoma of the colon. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:A26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, Yahalom J. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3785-3793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Eshghabadi M, Shojania AM, Carr I. Isolated granulocytic sarcoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:912-917. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Breccia M, D’Andrea M, Mengarelli A, Morano SG, D’Elia GM, Alimena G. Granulocytic sarcoma of the pancreas successfully treated with intensive chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. Eur J Haematol. 2003;70:190-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Breccia M, Mandelli F, Petti MC, D’Andrea M, Pescarmona E, Pileri SA, Carmosino I, Russo E, De Fabritiis P, Alimena G. Clinico-pathological characteristics of myeloid sarcoma at diagnosis and during follow-up: report of 12 cases from a single institution. Leuk Res. 2004;28:1165-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |