Published online Jan 15, 2016. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i1.67

Peer-review started: June 24, 2015

First decision: August 25, 2015

Revised: September 22, 2015

Accepted: November 10, 2015

Article in press: November 11, 2015

Published online: January 15, 2016

Processing time: 204 Days and 22.6 Hours

For a long time, treatment of peritoneal metastases (PM) was mostly palliative and thus, this status was link with “terminal status/despair”. The current multimodal treatment strategy, consisting of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), has been strenuously achieved over time, but seems to be the best treatment option for PM patients. As we reviewed the literature data, we could emphasize some milestones and also, controversies in the history of proposed multimodal treatment and thus, outline the philosophy of this approach, which seems to be an unusual one indeed. Initially marked by nihilism and fear, but benefiting from a remarkable joint effort of human and material resources (multi-center and -institutional research), over a period of 30 years, CRS and HIPEC found their place in the treatment of PM. The next 4 years were dedicated to the refinement of the multimodal treatment, by launching research pathways. In selected patients, with requires training, it demonstrated a significant survival results (similar to the Hepatic Metastases treatment), with acceptable risks and costs. The main debates regarding CRS and HIPEC treatment were based on the oncologists’ perspective and the small number of randomized clinical trials. It is important to statement the PM patient has the right to be informed of the existence of CRS and HIPEC, as a real treatment resource, the decision being made by multidisciplinary teams.

Core tip: The multimodal treatment of peritoneal metastases (PM), involving cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, has been strenuously achieved over time, but seems to be the best treatment option, for selected cases. This paper addresses data about the multimodal treatment strategy, focused to patient’s survival, the key indicator for assessing results, in the case of PM. Also, it were highlighted the treatment key aspects and the controversies, high in the 35 years of treatment implementing. By understanding the philosophy of multimodal treatment, physicians will be able to offer an alternative to the routine systemic chemotherapy.

- Citation: Lungoci C, Mironiuc AI, Muntean V, Oniu T, Leebmann H, Mayr M, Piso P. Multimodality treatment strategies have changed prognosis of peritoneal metastases. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2016; 8(1): 67-82

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v8/i1/67.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v8.i1.67

Peritoneal metastases (PM) were described by Sampson et al[1] (1931) in an ovarian cancer patient. For a long time since then, treatment was mostly palliative and thus, PM was linked to “terminal status/despair”. The current multimodal treatment consisting of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has been strenuously achieved over time, but seems to be the best treatment option for selected PM cases.

As we reviewed the literature data, we could emphasize some milestones and also, controversies in the history of PM treatment and thus, outline the philosophy of proposed multimodal radical treatment, which seems to be an unusual one indeed. To understand this radical treatment, we start with the natural evolution of PM and “conventional” systemic chemotherapy approach, in fact the treatment of choice for stage IV cancer, regardless of the dissemination type and location. Four periods must be considered in the evolution of “dedicated” PM treatment: Before 1980; 1980-2000; 2000-2010 and 2010-present. The first time period, before 1980, was a period of palliative intraperitoneal treatment of ascites. In 1980-2000 were proposed the methods and define the foundation laying for a new multimodal approach of PM by intraperitoneal chemotherapy and CRS. The next periods, until 2010, were those of the progressive development of dedicated multimodal treatment strategy, concluding with the actual CRS-HIPEC. From 2010, the studies were focused about new research pathways. The PM treatment approach related survival was the main issue considered in this review.

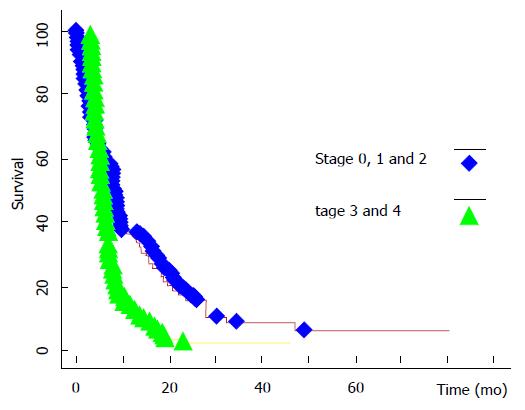

In the literature concerned with PM, the EVOCAPE I study[2] is classical and it reflected the natural evolution of patients with non-gynecological PM. The mean survival (mS) was 6 mo, significantly correlated with the PM stage (Figure 1), according Gilly system[3] (nodules/lumps < 5 mm: 9.8 mo; > 2 cm: 3.1 mo). PM of pancreatic origin had the lowest mS (2.9 mo), followed by PM of gastric origin (6.5 mo) and of colorectal origin (6.9 mo). The degree of differentiation had no influence on survival.

Several other “historical”[4-6] studies confirmed the unfavorable prognosis of PM. Ascites is a negative prognostic factor: In pancreatic cancer, median survival (MS) was < 1 mo, with an important negative impact on the quality of life. Surgery was aimed at palliating gastrointestinal complications, as it was contraindicated in patients with gastric, pancreatic tumors or ascites[4]. In colorectal cancer (marked by a favorable biological pattern), MS was significantly less for synchronous PM than that in metachronous (7 mo vs 28 mo, P < 0.001)[6].

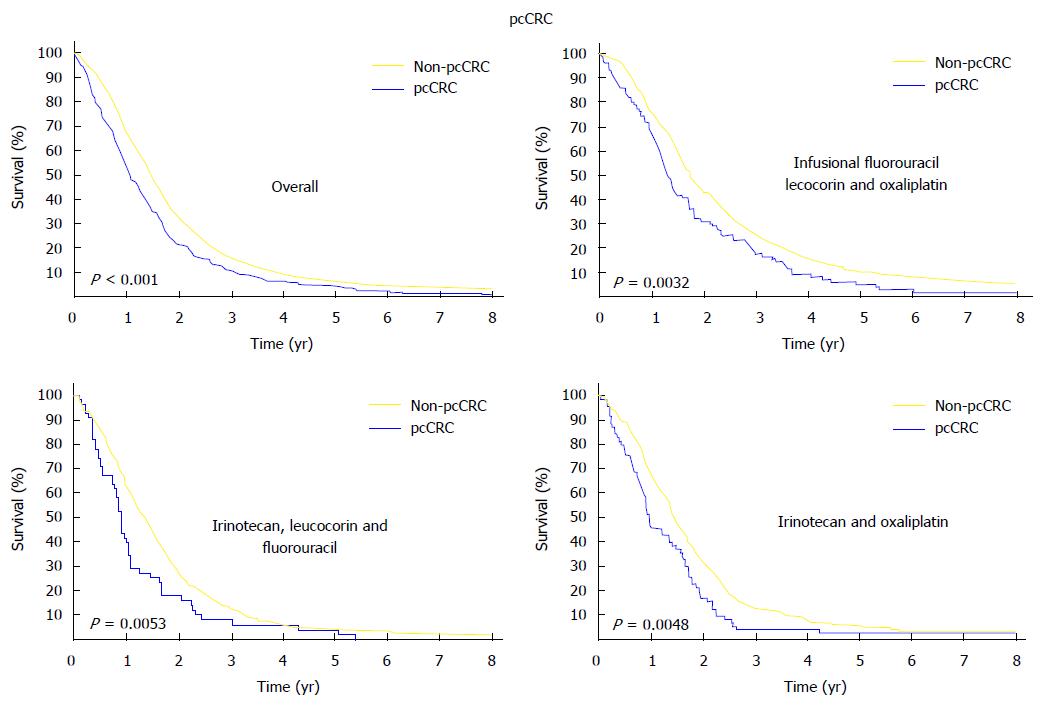

Recent studies on colorectal cancer compared patients having only PM, as a distant metastatic location, with patients having other systemic dissemination. Franko et al[7] (2012) revealed a significantly lower (P < 0.001) global MS (12.7 mo vs 17.6 mo) and disease-free survival (5.8 mo vs 7.2 mo) for patients with PM vs other metastatic locations. Also, the poor global MS of PM metastasis patient was unchanged by various chemotherapy regimens (Figure 2).

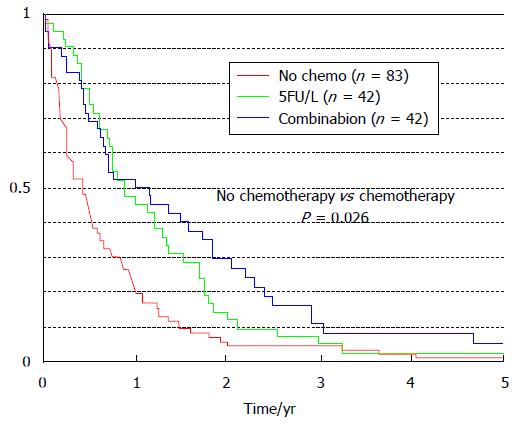

Systemic chemotherapy carried MS significant benefit (P = 0.026) in colorectal PM patients only compared to those patients who did not receive chemotherapy (Figure 3): Increasing from 5 mo without chemotherapy (95%CI: 3-7 mo) to 11 mo with the fluorouracil-leucovorin protocol (95%CI: 6-9 mo), and to 12 mo with the oxaliplatin-irinotecan protocol (95%CI: 4-20 mo)[8].

Despite the progressive development of systemic chemotherapy, in a population-based study, Lemmens et al[9] confirmed the poor MS in PM patients (1995-2001: 7 mo; 2002-2008: 8 mo), unlike that of patients with liver metastases, which underwent improvement (1995-2001: 8 mo; 2002-2008: 12 mo).

The first attempts for a treatment approach of peritoneal malignancies began in 1950, with the sporadic use of intraperitoneal chemotherapy for malignant ascites. For this intraperitoneal treatment, hemisulphur mustard[10], thiotepa[11], nitrogen mustard[12], quinacrine[13] and bleomycin[14] were used. Nitrogen mustard had a high digestive toxicity, so it was replaced by thiotepa (considered elective for ascites control in 1964), but even at that time it was foreseen that it would be replaced by 5-flurouracil in digestive cancer palliation[15]. Nevertheless, nitrogen mustard was the basis for developing further drugs: Cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, uramustine, ifosfamide, melphalan, and bendamustine.

In 1978-1980, the first documented data became available, at first referring to the clearance of intraperitoneal cytostatic drugs[16], then to circulating intraperitoneal cytostatic solutions, all thanks to the contributions of Speyer et al[17] and Spratt et al[18]. They were “the fathers” of regional intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Spratt augmented the cytostatic effect by hyperthermia using a specially designed device (Thermal Infusion Filtration System). Thus, the foundation was laid for a multimodal treatment of PM by normothermic and HIPEC.

The mechanism by which hyperthermia cytotoxic effects associating with and increasing the cytostatic drug effect is due to certain particularities of these drugs; studies regarding this aspect are exhaustive[19-25].

The key merit in developing and implementing this multimodal treatment strategy belongs to Sugarbaker, who outlined and detailed the premises substantiating it. The starting model was that of PM in appendiceal cancer[26]. The most important phase was the adjustment in the existing pathophysiological concept of PM, as a systemic disease and, consecutively, its treatment with systemic chemotherapy. In the new approach, the peritoneum was regarded as an organ (similar to the liver), the pathogeny of PM implying, first and foremost, peritoneal dissemination. Thus, it appears natural to use a regional treatment in PM[27-31]. Sugarbaker’s research was regarded mistrustfully, and 25 years had to pass before the “European contributions to the Sugarbaker protocol”[32] appeared: One multicenter retrospective study[33], two randomized prospective phase III studies[34,35] and the use of oxaliplatin and irinotecan as new cytostatic drugs in the protocols for intraperitoneal chemotherapy[36,37].

Sugarbaker also has the merit of being the first to have described and implemented the surgical procedures associated with regional chemotherapy, generically named “Peritonectomy”[38]. So, the road lay open for the PM multimodal treatment by CRS and HIPEC.

He then brought in other special aspects regarding the surgical technique of Peritonectomy procedures: Required electrocautery, circumferential skin traction, dissection of subpyloric space and falciform ligament[39-42]. He also described a method for staging PM and assessing the result of CRS, which were subsequently used in the majority of studies: The “Peritoneal Cancer Index” (PCI), based on the extension of peritoneal injury and the size of peritoneal deposits, respectively, the “Completeness of Cytoreduction Score” (CCRS), based on the size of the remaining peritoneal nodules/lumps[43].

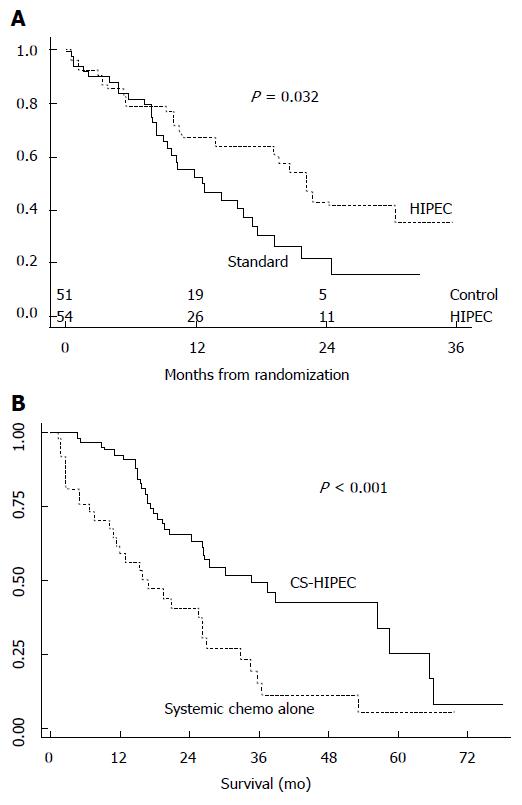

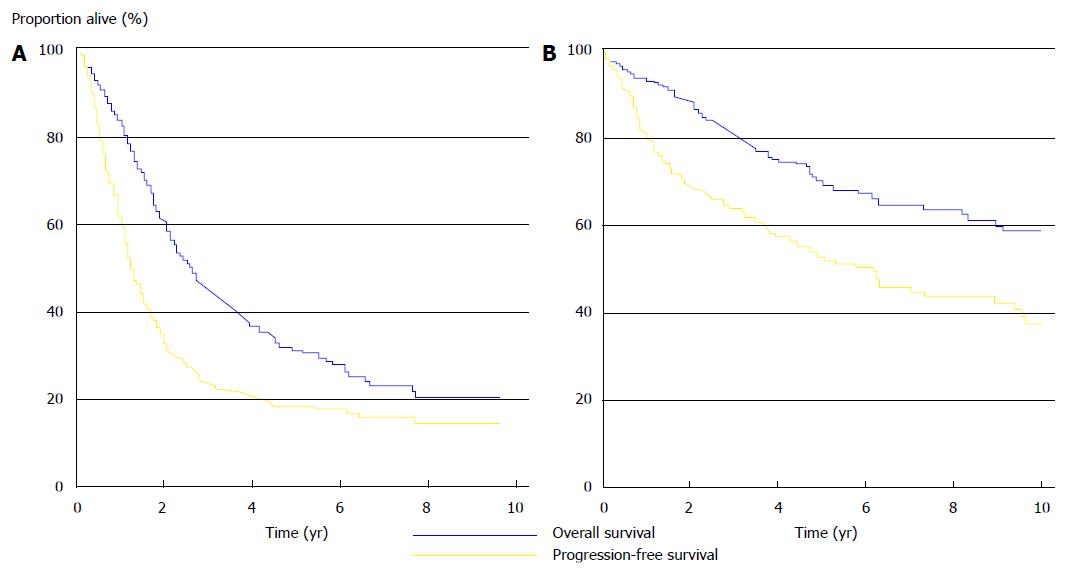

Although the number of patients progressively and significantly increased and the so-called “long-term survivors” were identified, it took about 20 years before the “confirmations of a multimodal treatment option for PM” appeared. The initiator was Verwaal (2003)[35], who carried out a randomized clinical trial for patients with colorectal PM. He showed that, during a mean follow-up of 21.6 mo, the MS of patients treated with CRS-HIPEC (22.3 mo) was significantly (P < 0.032) improved compared to patients treated with palliative surgery and systemic chemotherapy with fluorouracil-leucovorin (12.6 mo) (Figure 4A).

Verwaal’s research was confirmed by two other reference-worthy studies, which had the merit of comparing CRS-HIPEC with modern systemic chemotherapy treatment, in colorectal PM. Elias et al[44] (2009) compared systemic irinotecan-oxaliplatin chemotherapy with CRS-HIPEC. Global survival in the CRS-HIPEC group (2 years: 81%, 5 years: 51%) was significantly (P < 0.05) improved compared to the systemic chemotherapy (2 years: 65%, 5 years: 13%). Franko et al[45] (2010) analyzed systemic chemotherapy with irinotecan, oxalipatin, bevacizumab, and cetuximab. MS in the CRS-HIPEC treatment group (34.7 mo) was significantly (P < 0.01) longer than systemic chemotherapy (16.8 mo) (Figure 4B). It was emphasized that the best results were achieved by associating CRS-HIPEC treatment with systemic chemotherapy.

For gastric PM, studies also showed a benefit in terms of survival. The prospective randomized clinical trial GYMSSA[46] compared survival in patients treated with CRS-HIPEC and systemic chemotherapy vs systemic chemotherapy treatment alone. Within the limitation of a small number of patients, it showed a longer MS (11.3 mo vs 4.3 mo) for CRS-HIPEC treatment trial arm.

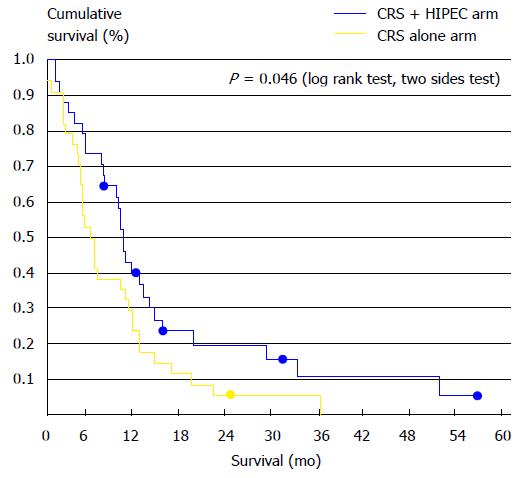

Likewise, Yang et al[47] showed in a phase III randomized clinical trial the importance of connecting CRS with HIPEC, in the treatment of PM of gastric cancer origin. The CRS-HIPEC association vs CRS alone significantly (P = 0.046) increased MS: 11 mo (95%CI: 10-11.9 mo) vs 6.5 mo (95%CI: 4.8-8.2 mo) (Figure 5).

A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials performed by Yan et al[48] showed that in advanced gastric cancer, HIPEC associated with surgery led to a significant increase in survival, compared with patients benefiting from surgery alone.

In addition to randomized clinical trials (the gold standard in the treatment implementation), there are a series of multi-center studies showing survival results for patients treated with CRS-HIPEC.

Thus, several multi-center studies, focused on pseudomyxoma peritonei, colorectal and ovarian cancers, were conducted in France (Figure 6). For the treatment of pseudomyxoma peritonei, CRS-HIPEC was designated the “gold standard” due to the yielded results (at 5 years: 73% global survival, 56% disease-free survival)[49]. Favorable results were shown for colorectal cancer (at 5 years: 27% global survival, 10% disease-free survival)[50], and also for ovarian cancer (global survival: Advanced forms 35.4 mo, recurrent forms 45.7 mo)[51].

The results were also confirmed by a long-term data analysis in the Netherlands, after the implementation of the CRS-HIPEC treatment: MS was 33 mo (95%CI: 28-38 mo) in colorectal cancer and 130 mo (95%CI: 98-162 mo) in pseudomyxoma peritonei (Figure 6)[52].

The experience of a reference center for PM treatment (St. George’s Hospital, Sydney) sustains the higher results obtained by the use of CRS-HIPEC treatment in pseudomyxoma peritonei (MS 104 mo; 5-year survival 75%) and colorectal cancer (MS 33 mo; 3-year survival 46%)[53].

A series of systematic reviews were conducted under the leadership of Sugarbaker, demonstrating a better survival for CRS-HIPEC treatment compared to conventional systemic chemotherapy. PMs of different origins were analyzed: Colorectal[54], gastric[48], ovarian[55] cancers, and malignant peritoneal mesothelioma[56]. Other systematic review studies also reported higher results for CRS-HIPEC in colorectal[57] and gastric[58] cancers.

All these studies (numerous and enrolling an increased number of patients) shows joint international efforts to identify the role of CRS-HIPEC in multimodal PM treatment. They have allowed the development of an important medical database which, by confirming the higher results in terms of survival and disease-free survival, upholds this treatment strategy. This is also confirmed by the evidence-based medicine approach studies[59].

The MS, as a result of CRS-HIPEC treatment, related to the tumor entities and study type, were presented in Table 1.

| Primitive tumor origin | Study type | Median survival (mo) |

| Colorectal | Randomized clinical trials | 22.3[35] |

| Single center experience | 33[53], 34.7[45] | |

| Systematic reviews | 13-29[54] | |

| Multi-institutional studies | 33[52] | |

| Gastric | Randomized clinical trials | 11.3[46], 11[47] |

| Pseudomyxoma peritonei | Single center experience | 104[53] |

| Multi-institutional studies | 130[52] | |

| Ovarian | Multi-institutional studies | 35.4-45.7[51] |

| Systematic reviews | 22-54[55] | |

| Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma | Systematic reviews | 34-92[56] |

As a recognition of the foundation-laying treatment of PM with CRS-HIPEC, this was included in the treatment guidelines in France[60], Germany[61], United Kingdom (http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/IPG331/PublicInfo), the Netherlands[52,62]. There are a number of ongoing symposia focused on Peritoneal Surface Malignancies, under the patronage of the European Society of Surgical Oncology, as well as a world congress.

The view of those who consider that multimodal PM treatment is “more of an experimental kind, based on common-sense evidence rather than on solid data”[63,64] is already obsolete. Even so, the confirmation of CRS-HIPEC, as an effective treatment approach by medical studies, such as randomized clinical trials, is not mandatory[65]. And more than that, the life of patients could be endangered by denying them a treatment resource, since the validation process may take as long as 40 years[66].

Unfortunately, there is no single perfect treatment option, valid in any setting, so the problems raised were concerned with treatment risk (morbidity, mortality, medical team risk), costs and with the indication of CRS-HIPEC, in terms of prognostic factors.

In the beginning, morbidity and mortality were the key factors initiating distrust among patients and physicians[67]. The causes of morbidity and mortality may well be suspected to belong to either CRS (surgery proper), or HIPEC (thermal effects of circulating fluid and toxic cytostatic drug effects). In a systematic-review study, morbidity was 21.5% and mortality 4.8%[68], but literature reports data within a large range: Morbidity 12%-67% and mortality 0%-9%. The main complications include digestive fistulae, postoperative bleeding, pleural-pulmonary complications, bone marrow suppression, hemodynamic instability and renal failure. Protective ileostomy, chest drain and postoperative thoracic imaging are routinely used.

However, it was shown that morbidity and mortality were not significantly increased, compared to extensive organ resection surgery (e.g., Whipple’s operation)[69]. Treatment complications were significantly correlated with the number of Peritonectomy procedures, left diaphragmatic Peritonectomy, duration of surgery and the number of large bowel anastomoses[70]. The global incidence for the 1th to 4th degree of gastrointestinal toxicities (according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events) was 17%, and for symptomatic surgical site infections incidence reached 35.85% (with a global morbidity of 45%)[71].

The learning curve must be respected by any medical procedure, even more so when it implies new skills for the surgeon. The “breaking points” of the learning curve in achieving complete CRS, of a morbidity less than 3th degree and an absence of treatment-related mortality are evaluated to be 141, 158 and 144 cases, respectively (the Milan experience), or 126, 134 and 60 cases, respectively (the Bentivoglio experience)[72].

As the Dutch model of CRS multimodal treatment implementation was analyzed, it was proven that, unlike in the initial stage (experience gathering), in the stage of treatment becoming standard, the percentage of radical surgeries increased significantly (66% vs 86%, P < 0.001) and major morbidity (3th-5th degree) decreased significantly (64% vs 32%, P < 0.001)[73].

If there existed accreditation centers and HIPEC registers, coursing through the learning curve could be faster[74]. Suggestions were made for training in CRS-HIPEC to begin during the residency programmer[75].

As for the risks the medical team are exposed to during HIPEC, it was shown in several pharmacological studies that, in relation to the HIPEC method (closed/open), with required training, these risks may be reduced to a minimum[76-78].

The costs implied by CRS-HIPEC treatment are definitely high, but financial calculations show that it is a better solution in terms of treatment results[53,79-81]. This is why in Germany, HIPEC is adopted, considered a surgical procedure and coded as such[61].

One of today’s challenges in treating PM is patient selection. This is why literature studies are focused on factors/variables correlating with survival.

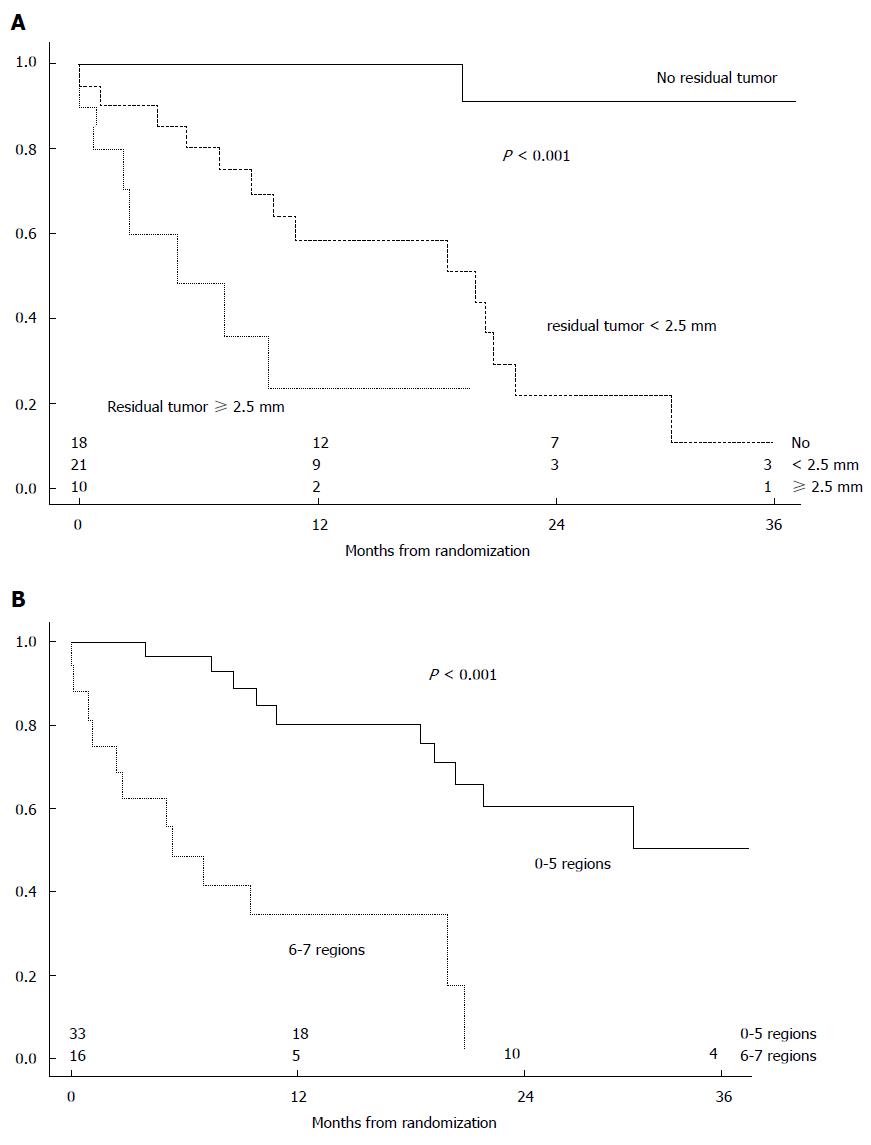

The randomized clinical trial performed by Verwaal et al[35] showed that in colorectal cancer, the variables with the highest impact are extension of PM and the radical feature of CRS (P < 0.0001) (Figure 7). The GYMSSA randomized clinical trial[46] also showed that essential conditions for a significant increase in survival in gastric cancer are complete CRS and a PCI ≤ 15.

A single-center experience, the most comprehensive in terms of the number of patients (1000 patients), shows that the prognostic factors significantly correlated with survival (P < 0.001) are: The performance index, the location of the primary tumor, the CCRS, and the center experience[82]. Another single-center experience (109 patients) correlated survival to the following factors: Histology of non-adenocarcinoma (P = 0.001), appendiceal location (P = 0.001), absence of liver metastases (P = 0.01), and complete resection of all gross disease (P < 0.001)[83].

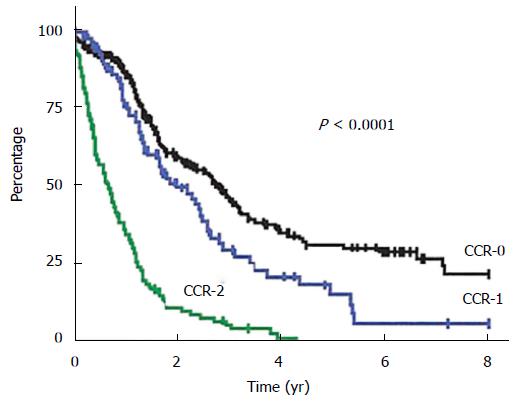

A multi-center French study shows that in colorectal cancer, CCRS is the most important prognostic factor for MS: 32.4 mo for complete vs 8.4 mo for incomplete CCRS (P < 0.001) (Figure 8)[33]. The multi-center SITILO study[84] also reveals in colorectal cancer the following independent prognostic variables correlated with survival: PCI, CCRS, and presence of hepatic metastases.

The consensus conference on PM treatment in colon cancer statutes that the indication of CRS-HIPEC treatment should be based on complete CRS[85].

All those prognostic factors are in dynamics, the trend being towards broadening the indication range, except for the radical feature of CRS: It is absolutely necessary that this should be complete, or at least optimal. Traditionally, the treatment approach in PM was reserved for colon or appendicular cancer, pseudomyxoma peritonei and peritoneal malignant mesothelioma, but now the range of indications includes rectal, gastric and ovarian cancers. The importance of PCI is not an absolute one, it must be correlated with primary tumor location (colonic PM origin vs gastric), histological grading (well and moderate differentiated vs poorly differentiated and undifferentiated), and the anatomical sites involved (Treitz ligament, porta hepatis and suprahepatic veins, coelic axis and mesenteric vessels). The presence of other systemic dissemination (abdominal or extra-abdominal) was a contraindication for the treatment approach in PM, but this is no longer (Figure 9) the case provided that complete CRS can be obtained[86-89].

Except for the patient status (evaluated by the performance index), the main CRS-HIPEC treatment contraindication is small bowel involvement[90], which is regarded as an independent prognostic factor[91-93].

A series of studies have confirmed the prognostic value of tumor grading in colorectal cancer. The “signet-ring cell”vs other types of differentiation has a significantly poorer MS (14.1 mo vs 35.1 mo; P < 0.01) and an increased relapse rate (68.8% vs 43.7%; P = 0.05)[94]. CRS-HIPEC treatment carries no survival benefit in colorectal PM with signet-ring cell histology, unless complete CRS is obtained[95]. Also, for the aggressive type of pseudomyxoma peritonei, systemic chemotherapy is indicated instead of CRS-HIPEC treatment[96].

In some studies, the prognostic factors were grouped into scores. The Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score may be used to stratify patients in clinical trials[97]. Different scores used in PM of colorectal origin are: The Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score, the Prognostic Score, and the Colorectal Peritoneal Score. The Colorectal Peritoneal Score (value ≥ 6) identifies patients with an unfavorable prognosis in terms of survival, and it does so better than PCI (value > 20) or the other two scoring systems[98].

At the same time, there are also reserved attitudes regarding the CRS-HIPEC approach of PM. This is mainly the position of oncologists, who are refractory to this treatment option, using the argument of the risk/benefit ratio. The theoretical premise they use is based on the lack of difference (pathophysiology, evolution, and treatment) between PM and other systemic dissemination. The treatment is not adapted, so different protocols of systemic chemotherapy (from the classic de Gramont chemotherapy to oxaliplatin, irinotecan and biological molecular agents) are given in different clinical trials, without considering the variances between the specific dissemination biology[99-101]. The indispensable condition that oncologists require for inclusion in a clinical trial is the presence of measurable lesions. In the case of PM, this condition is almost impossible to meet. Imaging modalities have a low sensitivity in detecting the peritoneal dissemination, and this is true for computer tomography as well as for magnetic resonance imaging. The only parameters based on which the results of CRS-HIPEC treatment may be assessed are disease-free survival and global survival.

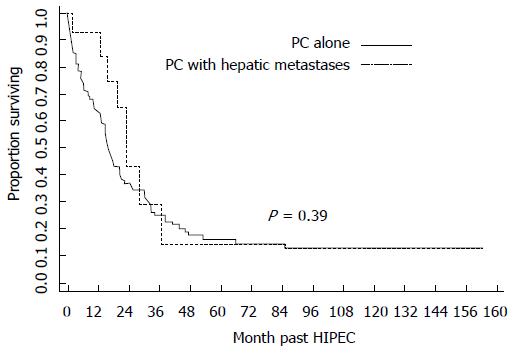

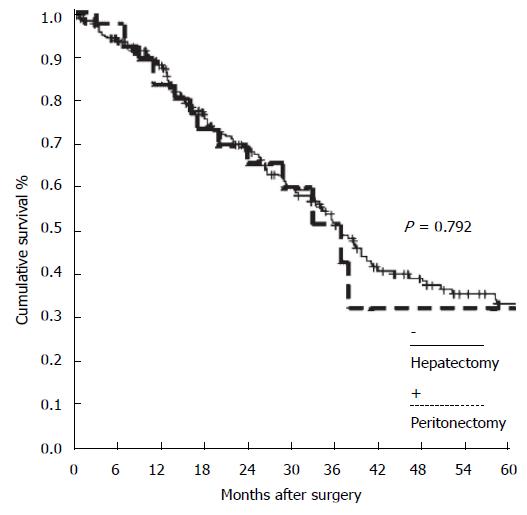

Furthermore, concerning the oncologists’ perspective, there is at least one more important argument supporting the dedicated multimodal treatment of PM: The studies matching hepatic metastases vs PM. These have shown that the pathway of dissemination are different and the treatment results are comparable (Figure 10), if treatment is potentially radical[102-104].

Nowadays, in colorectal cancer, by analogy with Hepatic Metastases, multimodal CRS-HIPEC treatment has been adopted and is the indicated approach for CP, in most institutions in the United States[31].

Currently, there is reason to talk about a higher level, where the problem of timing for CRS-HIPEC is raised. There are studies showing that PM prophylaxis is a valid approach.

“Proactive management” defines a treatment concept, targeting patients with a high risk to develop PM, and prescribes surgery with HIPEC. In colorectal cancer, this has brought about a significant results (P < 0.03), related to control group (only surgery), in terms of PM developed and local recurrence (4% vs 28%, over a 48-mo follow-up period). Patients had also significant longer MS (59.2 mo vs 52 mo; P < 0.04) and disease-free survival (P < 0.05)[105].

There was a hypothesis of second-look surgery at 1 year in patients at high risk for PM, after the first radical surgery for colorectal cancer. PM might be identified and treated at an earlier stage in about 55% of patients[106]. Such researches were also led for gastric cancer, with promising preliminary results[107,108].

In the same context of colorectal PM prophylaxis, the HIPEC laparoscopic approach was described and indicated after a mean interval of 6 wk (3-9 wk). This approach showed its feasibility[109].

The main issue is selecting high-risk patients for developing PM. The debated risk factors are: Invasion of or beyond the serosa (pT3, pT4), perforated tumors, positive peritoneal cytology (augmented by immunohistochemistry), occurrence of Krukenberg tumors and mucinous type of tumor[110]. Following a systematic review, three situations were identified to be associated with an increased frequency of metachronous PM development: Synchronous PM, ovarian metastases, and perforated tumor[111].

Despite all human and material efforts dedicated to CRS-HIPEC treatment, there are patients in whom evolving disease occurs. The right question is whether iterative treatment of PM might be a solution. There are at least three problems: Estimate the morbidity/mortality associated with the iterative treatment; documentation the prognostic factors; estimation the treatment results in terms of survival. The only few related studies define no clear attitude, supported by statistically significant data. Morbidity/mortality does not seem to differ significantly[112-114], only one single study reporting increased values[115].

HIPEC remains an important tool in the treatment of recurrent PM. Age (P = 0.049), time lapse between surgeries (P = 0.08), association of HIPEC (P = 0.005), and small bowel resections (P < 0.001) are statistically correlated with survival in PM appendiceal origin and malignant peritoneal mesothelioma[113]. The iterative approach of colorectal PM results in a MS of 22.6 mo, with the following survival percentages: 1 year - 94%; 2 years - 48%; 3 years - 12%[114].

The iterative approach treatment of the patient with PM and Hepatic Metastases has also promising results[116].

An important research pathway is the way by which chemotherapy might be integrated into various treatment approaches: Perioperative neoadjuvant; HIPEC; bidirectional intraoperative; early postoperative intraperitoneal. The multidisciplinary approach of PM is based on treatment with complete CRS. Unfortunately, this cannot be achieved in approximately 70% of patients[31].

The place of systemic chemotherapy in PM multimodal treatment is difficult to assess. There are definite reports regarding the results of perioperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy, demonstrated by histological response in colon cancer[117] and by increased survival in appendix cancer[118]. Likewise, in gastric cancer, survival benefits have been shown for perioperative neoadjuvant and early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy[119].

The complexity of multimodal treatment approach is also certified by the wide range of cytostatic drugs and the occurrence of new principles. It is possible that Mitomycin C, in colorectal PM, in the context of complete CRS, may yield superior survival results compared to oxaliplatin[120]. For gastric PM, catumaxomab seems to confirm positive results[119], but in colorectal PM, bevacizumab leads to a double mortality rate after CRS-HIPEC treatment[121].

Furthermore, as far as the array of CRS treatment is concerned, along with visceral resection and Peritonectomy procedures, surgery on the urinary tract was assessed. Partial cystectomy and ureter segmental resection were the most used. There was no further increase in the recorded morbidity or mortality and survival was comparable to that of patients with CRS-HIPEC without urinary tract surgery[122,123]. The same statute was dedicated to the hepatobiliary procedures[124].

At present, there are over 50 clinical trials underway, aimed at assessing multimodal radical PM treatment (http://clinicaltrialsfeeds.org/clinical-trials/results/term=HIPEC). Out of these, some were reported in the literature: GASTRICHIP (D2 gastric resection and HIPEC for locally advanced gastric cancer)[125], COMBATAC (multimodal treatment of PM of appendiceal and colorectal origin)[126], NCT01095523 (second-look and CRS-HIPEC treatment for colorectal cancer at risk for PM)[127].

Key aspects and PM model in the evolution of multimodal treatment strategies

We summarized the key aspects of the evolution of multimodal treatment strategies in Table 2.

| Period | PM treatment | Key aspects | PM model |

| All the period | “Conventional” systemic chemotherapy | Significant lower survival for PM vs other type of metastases | Colo-rectal |

| 1950-1980 | “Dedicated” intraperitoneal treatment - Palliative treatment | The basis for developing further cytostatic drugs | Malignant ascites |

| 1980-2000 | “Dedicated” intraperitoneal treatment - Multimodal radical treatment | Regional intraperitoneal normothermic and hyperthermic chemotherapy | Appendicular |

| Peritonectomy procedures | |||

| Define PCI and CCRS | |||

| 2000-2010 | Multimodal radical treatment - confirmation, aspects, patient selection, controversies | Significant higher survival vs palliative surgery and diverse systemic chemotherapy regimes | Colo-rectal |

| Acceptable morbidity and mortality, no significant risk for medical team | Appendicular | ||

| Respect de learning curve | Pseudomyxoma peritonei | ||

| High costs | Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma | ||

| Define the prognostic factors | Gastric | ||

| Position of oncologists | Ovarian | ||

| Comparison with hepatic metastases | PM with hepatic metastases | ||

| 2010-2014 | Multimodal treatment – research pathways | PM prophylaxis | High-risk patients for developing PM |

| Laparoscopic HIPEC | Recurrent PM | ||

| Integration of chemotherapy with surgery | |||

| Extension of CRS |

Initially marked by nihilism and fear, but benefiting from a remarkable joint effort of human and material resources (multi-center and -institutional research), over a period of 30 years, CRS-HIPEC found its place in the multimodal treatment of PM. The next 4 years were dedicated to the refinement of multimodal treatment, by launching research pathways. In selected patients, with requires training, it demonstrated a significant survival results (similar to the Hepatic Metastases treatment), with acceptable risks and costs. Also, CRS-HIPEC opens a lot of new opportunities with reference to the patients’ selection and adopted methodology of this multimodal treatment.

The main debates regarding CRS-HIPEC were based on the oncologists’ perspective and the small number of randomized clinical trials. It is hard to find a common view on different challenges, raised by CRS-HIPEC in the treatment of PM. Probably, Dr. Bernard Fisher met the same mistrust as he revolutionized breast cancer treatment and the same could be said about the surgical approach to metastatic melanoma. Indeed, there is a discrepancy between the great number of multi-center, -institutional studies and the small number of randomized clinical trials.

We may say that there are a series of determining factors, for the long-term assessment of multimodal PM treatment and the bias in medical studies type. Treatment complexity, results from the interaction between different therapeutic principles (surgery, chemotherapy, and hyperthermia), are an essential factor. Also, the peritoneal cavity is a complex anatomical space, and the pathogenesis of PM is indeed multifactorial conditioning (loco-regional and systemic dissemination). Not least, the multidisciplinary approach of PM implies the teamwork of specialists with different training, treatment concepts and results assessment, making it difficult to find a common view.

It is important to statement the patients with colo-rectal, appendicular, gastric, and ovarian peritoneal carcinomatosis, as well as patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei and peritoneal malignant mesothelioma must be informed about CRS-HIPEC as a valid treatment resource. The eligibility criteria for patients’ selection will be assessed by multidisciplinary teams, in high level, dedicated treatment centers, according to the performance index, PCI, histological grading, the perspective to obtaining a complete CRS, and the availability of sustaining chemotherapy protocols.

P- Reviewer: Caronna R, Garcia-Vallejo L, Mais V, Sammartino P S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Sampson JA. Implantation Peritoneal Carcinomatosis of Ovarian Origin. Am J Pathol. 1931;7:423-444.39. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O, Beaujard AC, Rivoire M, Baulieux J, Fontaumard E, Brachet A, Caillot JL, Faure JL. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE 1 multicentric prospective study. Cancer. 2000;88:358-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gilly FN, Carry PY, Sayag AC, Brachet A, Panteix G, Salle B, Bienvenu J, Burgard G, Guibert B, Banssillon V. Regional chemotherapy (with mitomycin C) and intra-operative hyperthermia for digestive cancers with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:124-129. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Chu DZ, Lang NP, Thompson C, Osteen PK, Westbrook KC. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in nongynecologic malignancy. A prospective study of prognostic factors. Cancer. 1989;63:364-367. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Glehen O, Osinsky D, Beaujard AC, Gilly FN. Natural history of peritoneal carcinomatosis from nongynecologic malignancies. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12:729-739, xiii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jayne DG, Fook S, Loi C, Seow-Choen F. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1545-1550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 598] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Franko J, Shi Q, Goldman CD, Pockaj BA, Nelson GD, Goldberg RM, Pitot HC, Grothey A, Alberts SR, Sargent DJ. Treatment of colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis with systemic chemotherapy: a pooled analysis of north central cancer treatment group phase III trials N9741 and N9841. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:263-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 440] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Pelz JO, Chua TC, Esquivel J, Stojadinovic A, Doerfer J, Morris DL, Maeder U, Germer CT, Kerscher AG. Evaluation of best supportive care and systemic chemotherapy as treatment stratified according to the retrospective peritoneal surface disease severity score (PSDSS) for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lemmens VE, Klaver YL, Verwaal VJ, Rutten HJ, Coebergh JW, de Hingh IH. Predictors and survival of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2717-2725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Green TH. Hemisulfur mustard in the palliation of patients with metastatic ovarian carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1959;13:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kottmeier HL. Treatment of ovarian cancer with thiotepa. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1968;11:428-438. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Jordan E, Karnicka-Mlodkowska H. [Intrapleural and intraperitoneal instillation of nitrogen mustard in palliative treatment of malignant effusions]. Pol Tyg Lek. 1971;26:676-678. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Lee M, Boyes DA. The use of quinacrine hydrochloride for the control of malignant serous effusions. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1971;78:843-844. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Baas EU, Krönig B. [Volume determination of ascites using intraperitoneal bromsulphalein administration]. Verh Dtsch Ges Inn Med. 1971;77:1374-1376. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hart GD. Palliative management of gastrointestinal cancer. Can Med Assoc J. 1964;90:1265-1268. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Dedrick RL, Myers CE, Bungay PM, DeVita VT. Pharmacokinetic rationale for peritoneal drug administration in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62:1-11. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Speyer JL, Myers CE. The use of peritoneal dialysis for delivery of chemotherapy to intraperitoneal malignancies. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1980;74:264-269. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Spratt JS, Adcock RA, Muskovin M, Sherrill W, McKeown J. Clinical delivery system for intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1980;40:256-260. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Hahn GM, Braun J, Har-Kedar I. Thermochemotherapy: synergism between hyperthermia (42-43 degrees) and adriamycin (of bleomycin) in mammalian cell inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:937-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Urano M, Ling CC. Thermal enhancement of melphalan and oxaliplatin cytotoxicity in vitro. Int J Hyperthermia. 2002;18:307-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mohamed F, Marchettini P, Stuart OA, Urano M, Sugarbaker PH. Thermal enhancement of new chemotherapeutic agents at moderate hyperthermia. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:463-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Smythe WR, Mansfield PF. Hyperthermia: has its time come? Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:210-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lepock JR. How do cells respond to their thermal environment? Int J Hyperthermia. 2005;21:681-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: Rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:68-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pelz JO, Vetterlein M, Grimmig T, Kerscher AG, Moll E, Lazariotou M, Matthes N, Faber M, Germer CT, Waaga-Gasser AM. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis: role of heat shock proteins and dissecting effects of hyperthermia. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1105-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sugarbaker PH, Chang D, Koslowe P. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from appendiceal cancer: A paradigm for treatment of abdomino-pelvic dissemination of gastrointestinal malignancy. Eur Surg. 1996;28:4-8. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sugarbaker PH. Metastatic inefficiency: the scientific basis for resection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol Suppl. 1993;3:158-160. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Sugarbaker PH. It’s what the surgeon doesn’t see that kills the patient. J Nippon Med Sch. 2000;67:5-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sugarbaker PH. Overview of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Cancerologia. 2008;3:119-124. |

| 30. | Sugarbaker PH. Surgical responsibilities in the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:713-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sugarbaker PH. Cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic perioperative chemotherapy for selected patients with peritoneal metastases from colorectal cancer: a new standard of care or an experimental approach? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:309417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gómez Portilla A, Cendoya I, Olabarría I, Martínez de Lecea C, Gómez Martínez de Lecea C, Gil A, Martín E, Muriel J, Magrach L, Romero E. The European contribution to “Sugarbaker’s protocol” for the treatment of colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101:97-102, 103-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Glehen O, Kwiatkowski F, Sugarbaker PH, Elias D, Levine EA, De Simone M, Barone R, Yonemura Y, Cavaliere F, Quenet F. Cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: a multi-institutional study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3284-3292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 860] [Cited by in RCA: 882] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Elias D, Delperro JR, Sideris L, Benhamou E, Pocard M, Baton O, Giovannini M, Lasser P. Treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: impact of complete cytoreductive surgery and difficulties in conducting randomized trials. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:518-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, van Sloothen GW, van Tinteren H, Boot H, Zoetmulder FA. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3737-3743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1396] [Cited by in RCA: 1512] [Article Influence: 68.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Elias DM, Sideris L. Pharmacokinetics of heated intraoperative intraperitoneal oxaliplatin after complete resection of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12:755-769, xiv. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Elias D, Matsuhisa T, Sideris L, Liberale G, Drouard-Troalen L, Raynard B, Pocard M, Puizillou JM, Billard V, Bourget P. Heated intra-operative intraperitoneal oxaliplatin plus irinotecan after complete resection of peritoneal carcinomatosis: pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and tolerance. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1558-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sugarbaker PH. Dissection by electrocautery with a ball tip. J Surg Oncol. 1994;56:246-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Sugarbaker PH. The subpyloric space: an important surgical and radiologic feature in pseudomyxoma peritonei. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:443-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Sugarbaker PH. Circumferential cutaneous traction for exposure of the layers of the abdominal wall. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:472-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sugarbaker PH. Pont hepatique (hepatic bridge), an important anatomic structure in cytoreductive surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:251-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Sugarbaker PH. Technical Handbook for the Integration of Cytoreductive Surgery and Perioperative Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy into the Surgical Management of Gastrointestinal and Gynecologic Malignancy. 4th ed. Michigan: The Ludann Company Grand Rapids 2005; 19-24. |

| 44. | Elias D, Lefevre JH, Chevalier J, Brouquet A, Marchal F, Classe JM, Ferron G, Guilloit JM, Meeus P, Goéré D. Complete cytoreductive surgery plus intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia with oxaliplatin for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 618] [Cited by in RCA: 667] [Article Influence: 41.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Franko J, Ibrahim Z, Gusani NJ, Holtzman MP, Bartlett DL, Zeh HJ. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion versus systemic chemotherapy alone for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer. 2010;116:3756-3762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Rudloff U, Langan RC, Mullinax JE, Beane JD, Steinberg SM, Beresnev T, Webb CC, Walker M, Toomey MA, Schrump D. Impact of maximal cytoreductive surgery plus regional heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) on outcome of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of gastric origin: results of the GYMSSA trial. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:275-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Yang XJ, Huang CQ, Suo T, Mei LJ, Yang GL, Cheng FL, Zhou YF, Xiong B, Yonemura Y, Li Y. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: final results of a phase III randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1575-1581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Yan TD, Black D, Sugarbaker PH, Zhu J, Yonemura Y, Petrou G, Morris DL. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials on adjuvant intraperitoneal chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2702-2713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Elias D, Gilly F, Quenet F, Bereder JM, Sidéris L, Mansvelt B, Lorimier G, Glehen O. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: a French multicentric study of 301 patients treated with cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:456-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Elias D, Gilly F, Boutitie F, Quenet F, Bereder JM, Mansvelt B, Lorimier G, Dubè P, Glehen O. Peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis treated with surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: retrospective analysis of 523 patients from a multicentric French study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:63-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Bakrin N, Bereder JM, Decullier E, Classe JM, Msika S, Lorimier G, Abboud K, Meeus P, Ferron G, Quenet F. Peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with cytoreductive surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) for advanced ovarian carcinoma: a French multicentre retrospective cohort study of 566 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:1435-1443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Kuijpers AM, Mirck B, Aalbers AG, Nienhuijs SW, de Hingh IH, Wiezer MJ, van Ramshorst B, van Ginkel RJ, Havenga K, Bremers AJ. Cytoreduction and HIPEC in the Netherlands: nationwide long-term outcome following the Dutch protocol. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4224-4230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Chua TC, Liauw W, Morris DL. The St George Hospital Peritoneal Surface Malignancy Program--where are we now? ANZ J Surg. 2009;79:416-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Yan TD, Black D, Savady R, Sugarbaker PH. Systematic review on the efficacy of cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4011-4019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Bijelic L, Jonson A, Sugarbaker PH. Systematic review of cytoreductive surgery and heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in primary and recurrent ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1943-1950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Yan TD, Welch L, Black D, Sugarbaker PH. A systematic review on the efficacy of cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for diffuse malignancy peritoneal mesothelioma. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:827-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Cao C, Yan TD, Black D, Morris DL. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cytoreductive surgery with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2152-2165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Matharu G, Tucker O, Alderson D. Systematic review of intraperitoneal chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1225-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Nissan A, Stojadinovic A, Garofalo A, Esquivel J, Piso P. Evidence-based medicine in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis: Past, present, and future. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:335-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Kavanagh M, Ouellet JF. [Clinical practice guideline on peritoneal carcinomatosis treatment using surgical cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy]. Bull Cancer. 2006;93:867-874. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Piso P, Leebmann H, März L, Mayr M. [Cytoreductive surgery for malignant peritoneal tumors]. Chirurg. 2015;86:38-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Verwaal VJ, Bruin S, Boot H, van Slooten G, van Tinteren H. 8-year follow-up of randomized trial: cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2426-2432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 710] [Cited by in RCA: 765] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Macrì A. New approach to peritoneal surface malignancies. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:9-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Evrard S, Mazière C, Désolneux G. HIPEC: standard of care or an experimental approach? Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e462-e463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Rawlins M, McCulloch P. When are randomised trials unnecessary? Picking signal from noise. BMJ. 2007;334:349-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Sugarbaker PH. Evolution of cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis: are there treatment alternatives? Am J Surg. 2011;201:157-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Spiegle G, Schmocker S, Huang H, Victor JC, Law C, McCart JA, Kennedy ED. Physicians’ awareness of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for colorectal cancer carcinomatosis. Can J Surg. 2013;56:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Gill RS, Al-Adra DP, Nagendran J, Campbell S, Shi X, Haase E, Schiller D. Treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC: a systematic review of survival, mortality, and morbidity. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:692-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Chua TC, Yan TD, Saxena A, Morris DL. Should the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy still be regarded as a highly morbid procedure?: a systematic review of morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg. 2009;249:900-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Saxena A, Yan TD, Morris DL. A critical evaluation of risk factors for complications after cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Surg. 2010;34:70-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Valle M, Federici O, Carboni F, Toma L, Gallo MT, Prignano G, Giannarelli D, Cenci L, Garofalo A. Postoperative infections after cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for peritoneal carcinomatosis: proposal and results from a prospective protocol study of prevention, surveillance and treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:950-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Kusamura S, Baratti D, Virzì S, Bonomi S, Iusco DR, Grassi A, Hutanu I, Deraco M. Learning curve for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in peritoneal surface malignancies: analysis of two centres. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:312-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Kuijpers AM, Aalbers AG, Nienhuijs SW, de Hingh IH, Wiezer MJ, van Ramshorst B, van Ginkel RJ, Havenga K, Heemsbergen WD, Hauptmann M. Implementation of a standardized HIPEC protocol improves outcome for peritoneal malignancy. World J Surg. 2015;39:453-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Pelz JO, Germer CT. [Morbidity and mortality of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion]. Chirurg. 2013;84:957-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Small T. Introduction of hyperthermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) to the surgery program. ORNAC J. 2013;31:12-17, 28-33. [PubMed] |

| 76. | Stuart OA, Stephens AD, Welch L, Sugarbaker PH. Safety monitoring of the coliseum technique for heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy with mitomycin C. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:186-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Schmid K, Boettcher MI, Pelz JO, Meyer T, Korinth G, Angerer J, Drexler H. Investigations on safety of hyperthermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) with Mitomycin C. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:1222-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Guerbet M, Goullé JP, Lubrano J. Evaluation of the risk of contamination of surgical personnel by vaporization of oxaliplatin during the intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:623-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Bonastre J, Chevalier J, Elias D, Classe JM, Ferron G, Guilloit JM, Marchal F, Meeus P, De Pouvourville G. Cost-effectiveness of intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Value Health. 2008;11:347-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Hultman B, Lundkvist J, Glimelius B, Nygren P, Mahteme H. Costs and clinical outcome of neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy followed by cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:112-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Mirnezami R, Mehta AM, Chandrakumaran K, Cecil T, Moran BJ, Carr N, Verwaal VJ, Mohamed F, Mirnezami AH. Cytoreductive surgery in combination with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival in patients with colorectal peritoneal metastases compared with systemic chemotherapy alone. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1500-1508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Levine EA, Stewart JH, Shen P, Russell GB, Loggie BL, Votanopoulos KI. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy: experience with 1,000 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:573-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Shen P, Levine EA, Hall J, Case D, Russell G, Fleming R, McQuellon R, Geisinger KR, Loggie BW. Factors predicting survival after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin C after cytoreductive surgery for patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Arch Surg. 2003;138:26-33. [PubMed] |

| 84. | Cavaliere F, De Simone M, Virzì S, Deraco M, Rossi CR, Garofalo A, Di Filippo F, Giannarelli D, Vaira M, Valle M. Prognostic factors and oncologic outcome in 146 patients with colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: Italian multicenter study S.I.T.I.L.O. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:148-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Esquivel J, Sticca R, Sugarbaker P, Levine E, Yan TD, Alexander R, Baratti D, Bartlett D, Barone R, Barrios P. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the management of peritoneal surface malignancies of colonic origin: a consensus statement. Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:128-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Varban O, Levine EA, Stewart JH, McCoy TP, Shen P. Outcomes associated with cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients with peritoneal surface disease and hepatic metastases. Cancer. 2009;115:3427-3436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Randle RW, Doud AN, Levine EA, Clark CJ, Swett KR, Shen P, Stewart JH, Votanopoulos KI. Peritoneal surface disease with synchronous hepatic involvement treated with Cytoreductive Surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1634-1638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Izzo F, Piccirillo M, Palaia R, Albino V, Di Giacomo R, Mastro AA. Management of colorectal liver metastases in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:345-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | de Cuba EM, Kwakman R, Knol DL, Bonjer HJ, Meijer GA, Te Velde EA. Cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for peritoneal metastases combined with curative treatment of colorectal liver metastases: Systematic review of all literature and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39:321-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Benizri EI, Bernard JL, Rahili A, Benchimol D, Bereder JM. Small bowel involvement is a prognostic factor in colorectal carcinomatosis treated with complete cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Chua TC, Koh JL, Yan TD, Liauw W, Morris DL. Cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis from small bowel adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:139-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Braam HJ, Boerma D, Wiezer MJ, van Ramshorst B. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy during primary tumour resection limits extent of bowel resection compared to two-stage treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:988-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Elias D, Mariani A, Cloutier AS, Blot F, Goéré D, Dumont F, Honoré C, Billard V, Dartigues P, Ducreux M. Modified selection criteria for complete cytoreductive surgery plus HIPEC based on peritoneal cancer index and small bowel involvement for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1467-1473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | van Oudheusden TR, Braam HJ, Nienhuijs SW, Wiezer MJ, van Ramshorst B, Luyer P, de Hingh IH. Poor outcome after cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis with signet ring cell histology. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Winer J, Zenati M, Ramalingam L, Jones H, Zureikat A, Holtzman M, Lee K, Ahrendt S, Pingpank J, Zeh HJ. Impact of aggressive histology and location of primary tumor on the efficacy of surgical therapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1456-1462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Faris JE, Ryan DP. Controversy and consensus on the management of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2013;14:365-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Esquivel J, Lowy AM, Markman M, Chua T, Pelz J, Baratti D, Baumgartner JM, Berri R, Bretcha-Boix P, Deraco M. The American Society of Peritoneal Surface Malignancies (ASPSM) Multiinstitution Evaluation of the Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score (PSDSS) in 1,013 Patients with Colorectal Cancer with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:4195-4201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Cashin PH, Graf W, Nygren P, Mahteme H. Comparison of prognostic scores for patients with colorectal cancer peritoneal metastases treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4183-4189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M, Homerin M, Hmissi A, Cassidy J, Boni C, Cortes-Funes H, Cervantes A, Freyer G. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2938-2947. [PubMed] |

| 100. | Douillard JY, Cunningham D, Roth AD, Navarro M, James RD, Karasek P, Jandik P, Iveson T, Carmichael J, Alakl M. Irinotecan combined with fluorouracil compared with fluorouracil alone as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1041-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2407] [Cited by in RCA: 2381] [Article Influence: 95.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 101. | Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335-2342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7832] [Cited by in RCA: 7730] [Article Influence: 368.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 102. | Cao CQ, Yan TD, Liauw W, Morris DL. Comparison of optimally resected hepatectomy and peritonectomy patients with colorectal cancer metastasis. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:529-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Tan GH, Teo MC, Chen W, Lee SY, Ng DW, Tham CK, Soo KC. Surgical management of colorectal peritoneal metastases: treatment and outcomes compared with hepatic metastases. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2013;44:170-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Blackham AU, Russell GB, Stewart JH, Votanopoulos K, Levine EA, Shen P. Metastatic colorectal cancer: survival comparison of hepatic resection versus cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2667-2674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Sammartino P, Sibio S, Biacchi D, Cardi M, Mingazzini P, Rosati MS, Cornali T, Sollazzo B, Atta JM, Di Giorgio A. Long-term results after proactive management for locoregional control in patients with colonic cancer at high risk of peritoneal metastases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1081-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Elias D, Goéré D, Di Pietrantonio D, Boige V, Malka D, Kohneh-Shahri N, Dromain C, Ducreux M. Results of systematic second-look surgery in patients at high risk of developing colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg. 2008;247:445-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Roviello F, Caruso S, Neri A, Marrelli D. Treatment and prevention of peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer by cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: overview and rationale. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:1309-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Saladino E, Fleres F, Mazzeo C, Pruiti V, Scollica M, Rossitto M, Cucinotta E, Macrì A. The role of prophylactic hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the management of serosal involved gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:2019-2022. [PubMed] |

| 109. | Sloothaak DA, Gardenbroek TJ, Crezee J, Bemelman WA, Punt CJ, Buskens CJ, Tanis PJ. Feasibility of adjuvant laparoscopic hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in a short stay setting in patients with colorectal cancer at high risk of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1453-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Sammartino P, Sibio S, Biacchi D, Cardi M, Accarpio F, Mingazzini P, Rosati MS, Cornali T, Di Giorgio A. Prevention of Peritoneal Metastases from Colon Cancer in High-Risk Patients: Preliminary Results of Surgery plus Prophylactic HIPEC. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:141585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Honoré C, Goéré D, Souadka A, Dumont F, Elias D. Definition of patients presenting a high risk of developing peritoneal carcinomatosis after curative surgery for colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:183-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Votanopoulos KI, Ihemelandu C, Shen P, Stewart JH, Russell GB, Levine EA. Outcomes of repeat cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of peritoneal surface malignancy. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:412-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Chua TC, Quinn LE, Zhao J, Morris DL. Iterative cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for recurrent peritoneal metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Williams BH, Alzahrani NA, Chan DL, Chua TC, Morris DL. Repeat cytoreductive surgery (CRS) for recurrent colorectal peritoneal metastases: yes or no? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:943-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Golse N, Bakrin N, Passot G, Mohamed F, Vaudoyer D, Gilly FN, Glehen O, Cotte E. Iterative procedures combining cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal recurrence: postoperative and long-term results. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:197-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Kianmanesh R, Scaringi S, Sabate JM, Castel B, Pons-Kerjean N, Coffin B, Hay JM, Flamant Y, Msika S. Iterative cytoreductive surgery associated with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin with or without liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2007;245:597-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Passot G, You B, Boschetti G, Fontaine J, Isaac S, Decullier E, Maurice C, Vaudoyer D, Gilly FN, Cotte E. Pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a new prognosis tool for the curative management of peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2608-2614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Bijelic L, Kumar AS, Stuart OA, Sugarbaker PH. Systemic Chemotherapy prior to Cytoreductive Surgery and HIPEC for Carcinomatosis from Appendix Cancer: Impact on Perioperative Outcomes and Short-Term Survival. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:163284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Montori G, Coccolini F, Ceresoli M, Catena F, Colaianni N, Poletti E, Ansaloni L. The treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in advanced gastric cancer: state of the art. Int J Surg Oncol. 2014;2014:912418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Prada-Villaverde A, Esquivel J, Lowy AM, Markman M, Chua T, Pelz J, Baratti D, Baumgartner JM, Berri R, Bretcha-Boix P. The American Society of Peritoneal Surface Malignancies evaluation of HIPEC with Mitomycin C versus Oxaliplatin in 539 patients with colon cancer undergoing a complete cytoreductive surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:779-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Eveno C, Passot G, Goéré D, Soyer P, Gayat E, Glehen O, Elias D, Pocard M. Bevacizumab doubles the early postoperative complication rate after cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1792-1800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Leapman MS, Jibara G, Tabrizian P, Franssen B, Yang MJ, Romanoff A, Hall SJ, Palese M, Sarpel U, Hiotis S. Genitourinary resection at the time of cytoreductive surgery and heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis is not associated with increased morbidity or worsened oncologic outcomes: a case-matched study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1153-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Votanopoulos KI, Randle RW, Craven B, Swett KR, Levine EA, Shen P, Stewart JH, Mirzazadeh M. Significance of urinary tract involvement in patients treated with cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:868-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Glockzin G, Renner P, Popp FC, Dahlke MH, von Breitenbuch P, Schlitt HJ, Piso P. Hepatobiliary procedures in patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1052-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 125. | Glehen O, Passot G, Villeneuve L, Vaudoyer D, Bin-Dorel S, Boschetti G, Piaton E, Garofalo A. GASTRICHIP: D2 resection and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in locally advanced gastric carcinoma: a randomized and multicenter phase III study. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |