Published online Feb 15, 2013. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v5.i2.34

Revised: September 26, 2012

Accepted: December 1, 2012

Published online: February 15, 2013

Diffuse intestinal ganglioneuromatosis is a hamartomatous polyposis characterized by a disseminated, intramural or transmural proliferation of neural elements involving the enteric plexuses. It has been associated with MEN II, neurofibromatosis type 1 and hamartomatous polyposis associated with phosphatase and tensin homolog mutation. We report the case of a female patient with a history of a breast and endometrial tumor who presented in a colonoscopy performed for rectal bleeding diffuse ganglioneuromatosis, which oriented the search for other characteristic findings of Cowden syndrome given the personal history of the patient. The presence of an esophagogastric polyposis was also noted. Cowden syndrome is characterized by skin lesions, but it is rarely diagnosed by these lesions, because they are usually overlooked. Intestinal polyposis is not a major diagnostic criterion but it is very useful for early diagnosis. The combination of colonic polyposis and glucogenic acanthosis should orient the diagnosis to Cowden syndrome.

- Citation: Herranz Bachiller MT, Barrio Andrés J, Pons F, Alcaide Suárez N, Ruiz-Zorrilla R, Sancho del Val L, Lorenzo Pelayo S, De La Serna Higuera C, Atienza Sánchez R, Perez Miranda M. Diffuse intestinal ganglioneuromatosis an uncommon manifestation of Cowden syndrome. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2013; 5(2): 34-37

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v5/i2/34.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v5.i2.34

Intestinal ganglioneuromatosis is a hamartomatous polyposis usually reported in children and uncommon in adults consisting of hyperplasia of the myenteric plexus and the enteric nerve fibers[1]. The most common symptoms caused are change in bowel habit and gastrointestinal bleeding. Diagnosis is always microscopic although the digitiform morphology of this type of polyps may be suggestive. It may be a single, multiple or diffuse polyposis, characterized by a disseminated, intramural or transmural proliferation of neural elements involving the enteric plexuses. The diffuse form has been related to systemic diseases such as MEN II, neurofibromatosis type 1 and hamartomatous polyposis associated with phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mutation, including Cowden syndrome, although ganglioneuromatosis has not been associated with any specific gene mutation[2]. Cowden syndrome is an autosomal dominant disease characterized by the presence of multiple hamartomas of ectodermal, mesodermal and endodermal origin, and an increased risk of development of malignant disease. The most typical finding is mucocutaneous lesions present in almost 100% of the cases[3]. It is also commonly associated with gastrointestinal polyposis, the most common histology being hamartomas, although fibromatous, lipomatous or hyperplastic polyps, adenomas and sometimes ganglioneuromas have also been reported. Many patients present several histological types simultaneously[4]. We report a case of intestinal ganglioneuromatosis that oriented the diagnosis to Cowden syndrome.

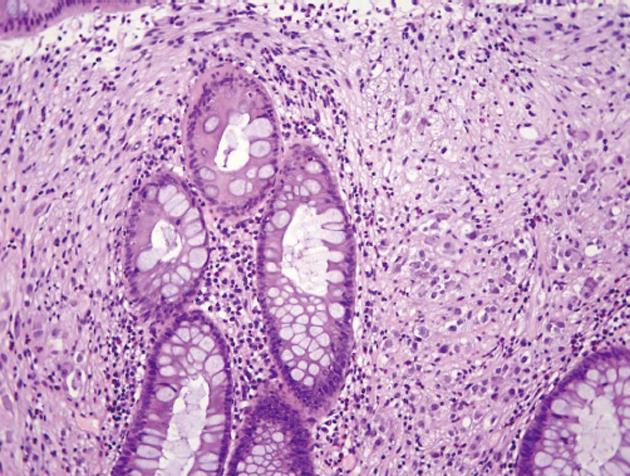

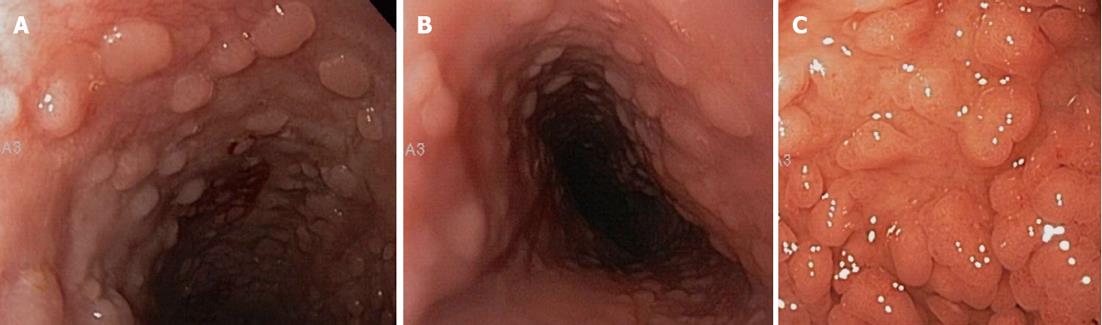

We report the case of a 40-year-old female patient who presented to the gastrointestinal clinic in 2005 for rectal bleeding associated with a change in bowel habit. She had as personal history at that time of hemithyroidectomy due to hyperfunctional thyroid nodules, a bilateral mastectomy for multicenter intraductal carcinoma and 4 abortions. Laboratory tests was performed with normal complete blood count, glucose, urea, creatinine, ions, liver profile, lipid profile, and hormone study. A colonoscopy was requested revealing multiple polyposis in all colon segments, with polypectomy of over 50 polyps being performed. Findings in the pathological study of the excised tissue were: hyperplastic, adenomatous polyps and ganglion cells in lamina propria of some excised polyps. In 2008, she required hysterectomy and right adnexectomy due to endometrial squamous metaplasia and an eroded ovarian cyst. That same year a colonoscopy was performed for postpolypectomy control in which multiple polypectomy was repeated. On this occasion, the pathological study revealed diffuse intestinal ganglioneuromatosis in the material provided (Figure 1). Based on these findings and given its possible relationship, it was decided to perform screening for MEN II, which was negative. Suspecting possible Cowden syndrome, a targeted skin examination was requested, in which multiple papular facial lesions were identified, some of them of papillomatous appearance, which were biopsied, with several showing pathological features of trichilemmomas. A gastroscopy was subsequently performed showing esophagogastric polyposis (Figure 2), with esophageal polyps consistent with glucogenic acanthosis. The patient met clinical diagnostic criteria for Cowden syndrome (Table 1), currently pending genetic study (PTEN gene). Associated pathology at the cerebellar level was discarded by magnetic resonance imaging. The recommended preventive follow-up was performed, requiring in 2010 thyroid resection of thyroid remnants due to papillary microcarcinoma and new endoscopic colonic polypectomies (Pathology report: ganglioneuromas with intestinal pneumatosis).

| Pathognomonic criteria |

| Lhermitte-duclos disease-adult |

| Mucocutaneous lesions |

| Trichilemmomas, facial |

| Acral keratoses |

| Papillomatous lesions |

| Major criteria |

| Breast cancer |

| Thyroid cancer (papillary or follicular) |

| Macrocephaly (≥ 97% ile) |

| Endometrial cancer |

| Minor criteria |

| Other structural thyroid lesions (e.g., adenoma, multinodular goiter) |

| Mental retardation (i.e., intelligence quotient ≤ 75) |

| Gastrointestinal hamartomas |

| Fibrocystic disease of the breast |

| Lipomas |

| Fibromas |

| Genitourinary tumours (e.g., uterine fibroids, renal cell carcinoma) or |

| genitourinary structural malformations |

| Uterine fibroids |

| Operational diagnosis in an individual (any of the following) |

| Mucocutaneous lesions alone if: |

| There are six or more facial papules, of which three or more must be trichilemmoma; or |

| Cutaneous facial papules and oral mucosal papillomatosis; or |

| Oral mucosal papillomatosis and acral keratoses; or |

| Palmoplantar keratoses, six or more |

| Two or more major criteria, but one must include macrocephaly or lhermitte-duclos disease |

| One major and three minor criteria; or |

| Four minor criteria |

| Operational diagnosis in a family where one individual is diagnostic for Cowden |

| One pathognomonic criterion |

| Any one major criterion with or without minor criteria |

| Two minor criteria |

| History of Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome |

Cowden syndrome is considered an uncommon syndrome of hamartomatous polyposis caused by germinal changes in the PTEN tumor suppressor gene localized on chromosome 10 (10q23)[5,6], which could be involved as a regulator of multiple processes of cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis, all of which are important processes for adequate cell growth. Other syndromes that have been associated with a mutation of this gene are the Bannayan-Riley-Rubalcaba syndrome, proteus and proteus-like syndrome and adult Lhermite-Duclos disease, as well as autism syndromes associated with macrocephalia[6].

The prevalence of Cowden syndrome has been estimated at 1/200 000-250 000 inhabitants in a German series published in 1999[7], but it is thought that its prevalence is underestimated as it is a difficult disease to diagnose because of the variability of its expression and since many of its manifestations may go unnoticed[5].

Diagnosis is based on clinical criteria, the most recent criteria from 2008 have been previously described. Our patient had 2 pathognomonic criteria (papillomatous papules, trichilemmomas), 3 major criteria (breast cancer, thyroid cancer, endometrial cancer) and 2 minor criteria (gastrointestinal hamartomas and benign thyroid disease). These criteria lead us to the diagnosis but do not provide an early diagnosis of syndrome, since the skin lesions, pathognomonic of this disease, usually go unnoticed and are diagnosed by a targeted examination when one starts to suspect this condition, as occurred also in our case. Gastrointestinal polyposis is considered a minor criterion due to the lack of systematic studies to determine its true frequency and histology[4]. It is actually a very common finding, with an estimated prevalence of up to 80% in patients with Cowden syndrome. In a series of 127 patients with PTEN gene mutation, the presence of gastrointestinal polyposis was seen in 50% of the total and in 93% of patients who underwent an endoscopy, thus indicating an underestimated frequency of this manifestation since an endoscopic study is performed in only a percentage of patients, generally those who are symptomatic[4]. The histopathology of the polyps found in colon is similar to that found in duodenum and stomach but not in the esophagus, where it is usually a diffuse glucogenic acanthosis, as in our case, and less commonly consists of pseudo polyps of inflammatory appearance. It has been suggested that the association of benign gastrointestinal polyposis and esophageal glucogenic acanthosis should be considered as a pathognomonic criterion for Cowden syndrome[3,8]. The implementation of surveillance programs in patients with hereditary diseases with an increased risk of malignancy is necessary but in the case of Cowden syndrome it is a controversial subject since the association with increased breast, thyroid and endometrial cancer is clear, but the association to other cancers including melanoma, renal cell or colon cancer has not been established due to the lack of sufficient data[6]. In the previously mentioned series of 127 patients[4], colorectal cancer was detected in 7.1% of patients, all under 50 years of age. Based on these data and the earlier published cases referring to a possible association between Cowden syndrome and colon carcinoma, numerous recommendations for colon cancer screening were made in this type of patients. From the laxest which recommend monitoring as in the general population starting after 50 years[9] to the strictest which recommend starting at 15 years and monitoring every 1-2 years[10], through an intermediate and more reasonable recommendation starting at 35 years, or earlier if there are symptoms, with a variable monitoring according to macroscopic and histopathological findings[4].

In conclusion, Cowden syndrome is a disease with increased risk of malignancy, whose clinical manifestations are highly variable making diagnosis difficult. Gastrointestinal polyposis is a common manifestation but systematic studies are required to reach a criterion of greater weight in diagnosis of this pathology. The histology if gastrointestinal polyps is varied, and the same patient may present 2 or more histological types, including ganglioneuromas, which when they are of the diffuse type orient the diagnosis more quickly to Cowden syndrome. Additional studies are needed to assess the malignization risk of this polyposis and unify the recommendations for colon cancer screening in this type of population.

P- Reviewer Raica M S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Chambonnière ML, Porcheron J, Scoazec JY, Audigier JC, Mosnier JF. [Intestinal ganglioneuromatosis diagnosed in adult patients]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2003;27:219-224. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Chan OT, Haghighi P. Hamartomatous polyps of the colon: ganglioneuromatous, stromal, and lipomatous. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1561-1566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kay PS, Soetikno RM, Mindelzun R, Young HS. Diffuse esophageal glycogenic acanthosis: an endoscopic marker of Cowden’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1038-1040. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Heald B, Mester J, Rybicki L, Orloff MS, Burke CA, Eng C. Frequent gastrointestinal polyps and colorectal adenocarcinomas in a prospective series of PTEN mutation carriers. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1927-1933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Farooq A, Walker LJ, Bowling J, Audisio RA. Cowden syndrome. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:577-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pilarski R. Cowden syndrome: a critical review of the clinical literature. J Genet Couns. 2009;18:13-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nelen MR, Kremer H, Konings IB, Schoute F, van Essen AJ, Koch R, Woods CG, Fryns JP, Hamel B, Hoefsloot LH. Novel PTEN mutations in patients with Cowden disease: absence of clear genotype-phenotype correlations. Eur J Hum Genet. 1999;7:267-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Umemura K, Takagi S, Ishigaki Y, Iwabuchi M, Kuroki S, Kinouchi Y, Shimosegawa T. Gastrointestinal polyposis with esophageal polyposis is useful for early diagnosis of Cowden’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5755-5759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Riegert-Johnson DL, Gleeson FC, Roberts M, Tholen K, Youngborg L, Bullock M, Boardman LA. Cancer and Lhermitte-Duclos disease are common in Cowden syndrome patients. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2010;8:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schreibman IR, Baker M, Amos C, McGarrity TJ. The hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: a clinical and molecular review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:476-490. [PubMed] |