Published online May 15, 2011. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v3.i5.71

Revised: April 23, 2011

Accepted: April 29, 2011

Published online: May 15, 2011

Flavonoids, secondary plant products which could be essential for normal physiology in humans and animals, may be the vitamins of the next century. Flavonoids belong to the polyphenols and possess antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic and anticarcinogenic properties. Among the various flavonoid species, tea flavonoids such as apigenin (from camomile) and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG from green tea) can be used for the prevention of intestinal neoplasia, especially for adenoma and cancer prevention in the gastrointestinal tract. Numerous experimental studies with molecular and biological end points support the therapeutic efficacy of bioflavonoids. Clinical studies with cohorts and case-control trials suggest that flavonoids are effective in tertiary bioprevention but, as yet, there are no controlled randomized clinical trials. Flavonoids can inhibit inflammatory pathways and could be useful for chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Flavonoid deficiency syndromes could be therapeutic targets in the future.

- Citation: Hoensch HP, Oertel R. Emerging role of bioflavonoids in gastroenterology: Especially their effects on intestinal neoplasia. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2011; 3(5): 71-74

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v3/i5/71.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v3.i5.71

At a conference of nutritional science a few years ago, it was suggested that flavonoids could become the vitamins of the next century. At that time I thought that this is an outrageous claim. However, since then there is mounting evidence that flavonoids could fulfil this promise.

Flavonoids are secondary plant metabolites that are ubiquitous in fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds and as plants, are parts of human nutrition[1,2]. Some of them exhibit a broad spectrum of physiological and pharmacological properties such as antioxidant, radical-scavenging, anti-inflammatory, anti-viral and -bacterial, anti-atherogenic and anti-carcinogenic activities[3]. It is reported that human intake of all flavonoids is a few hundred milligrams to 650 mg/d in our western diet. Their entry into the body takes place via the gastrointestinal tract and therefore this organ and especially the epithelial lining cells are exposed to fairly high concentrations of flavonoids[4]. There is some controversy about the bioavailability of nutritional flavonoids and about which type of flavonoids will be taken up and absorbed from the average food that we consume. Data on bioavailability vary wildly depending on many factors including the source, the specific molecular species, the presence of fat and the degree of food processing. Due to modern food technology, the flavonoid content of food is diminished, as can be shown in chocolate[5] and apple juice[6].

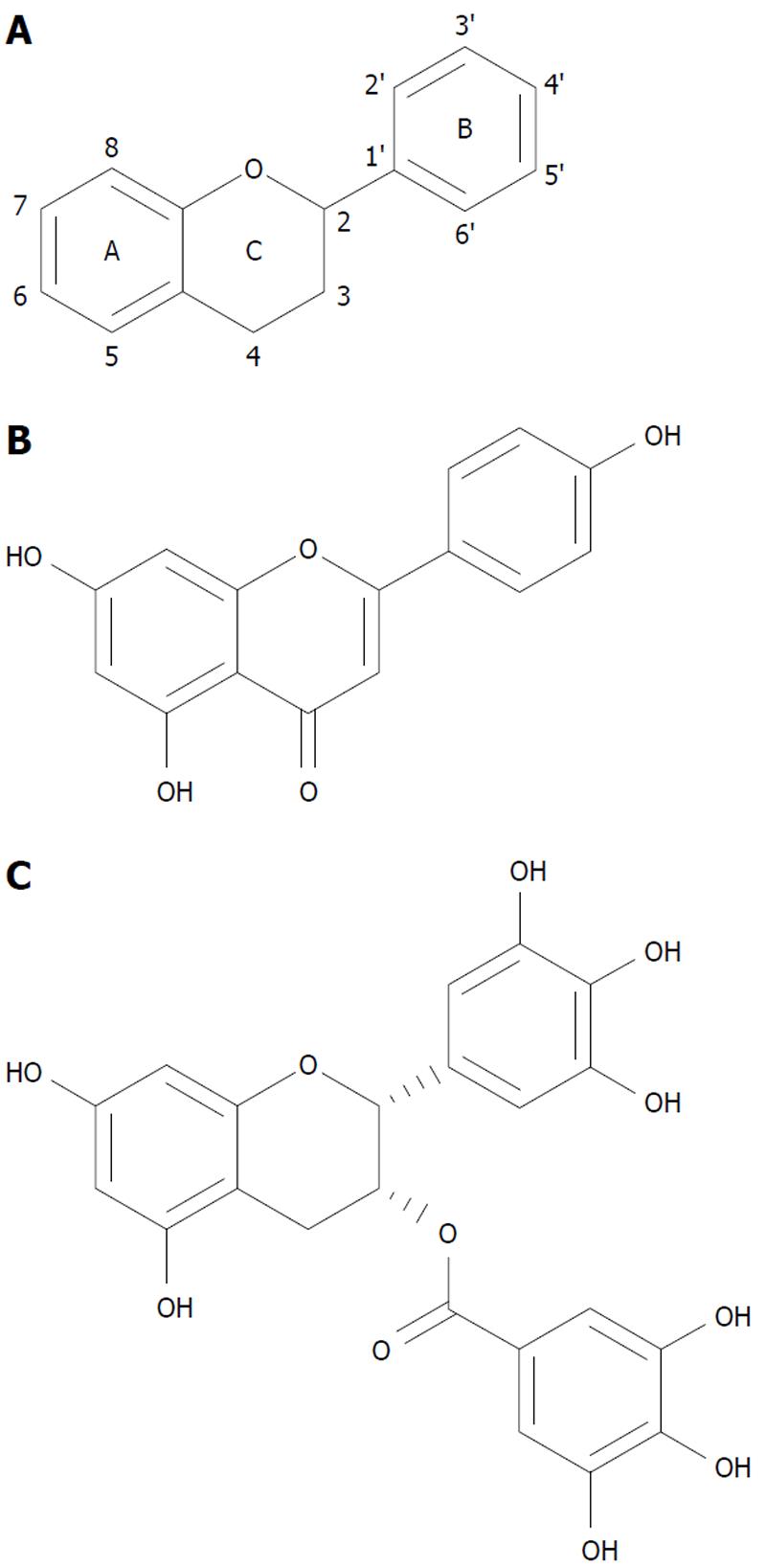

The most abundant flavonoids from nature originate from fruits (apples, onions and citrus fruits), teas (camomile, green tea), vegetables (cabbage, broccoli), seasonings (parsley, celery) and berries. These products of nature contain flavons (apigenin, luteolin), flavonols (quercetin, kaempferol), flavanols (epigallocatechin-3-gallate- EGCG), flavanons (naringenin, hesperidin) and isoflavons (genistein from soja) as well as anthocyanidins (from berries). The basic chemical structure of flavonoids is illustrated in Figure 1A and that of two of its major species (apigenin and EGCG) in Figure 1B and C.

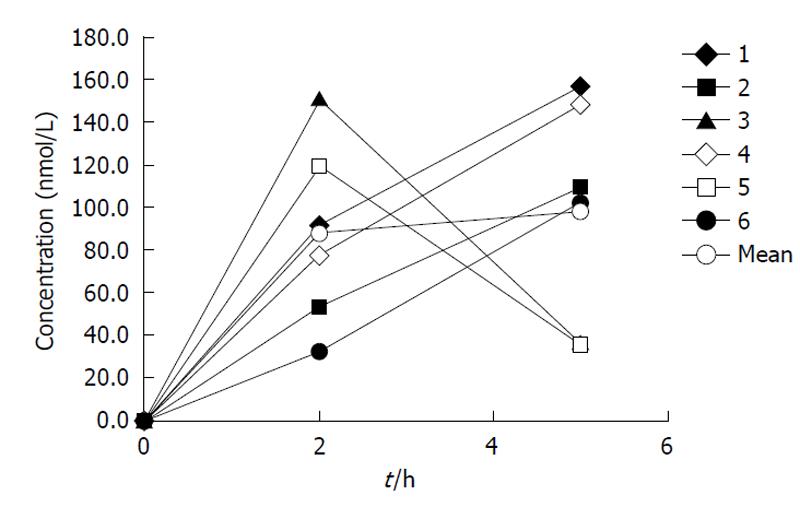

Epidemiological studies have indicated decreased cancer occurrence in people who regularly drink green tea and, conversely, low intake could be associated with an enhanced risk of cancer[4]. Several constituents, including apigenin 7-O-glucoside and EGCG which accounts for about 60%-70% of total catechins, have been studied with respect to their anti-cancerogenic activities and it appears that these substances could be the most potent compounds in tea for inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis of cancer cells[7]. Thus, regarding their safety, flavonoids are likely to have a potential value in preventive and therapeutic roles in cancerogenic conditions. Apigenin, a flavonoid present in camomile tea, parsley and celery, is a unique flavonoid because it is not detectable in the blood of individuals with a conventional western diet while other compounds like EGCG reach the central compartment and can be found in the serum[8]. We measured apigenin levels (50-150 nmol/L) after ingestion of 5 flavonoid tablets (Figure 2), each containing a mixture of tea flavonoids including apigenin (10 mg), EGCG (10 mg) and other tea flavonoids[9].

The results indicate that the absorption of food flavonoids from a conventional western diet is not sufficient to provide detectable and quantifiable apigenin levels. However, measurable exposure to at least apigenin can be found on nutritional supplements such as extracts from tea plants (camomile, green tea -“Flavo-Natin”®).

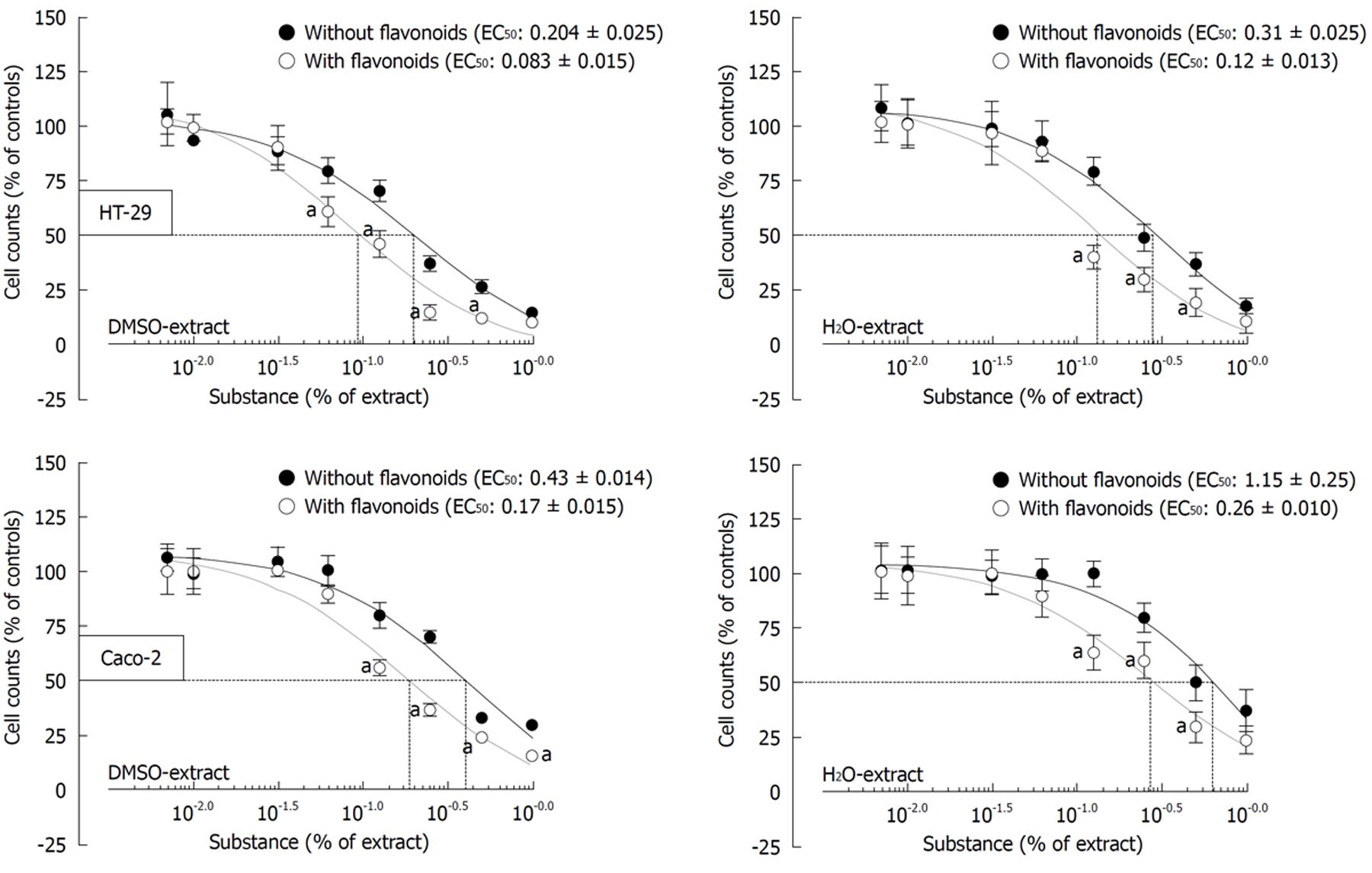

Increasingly, epidemiological and experimental studies demonstrate that modulation of the carcinogenic response by natural phytochemicals plays an important role in the prevention, mitigation and treatment of many diseases, especially in colorectal cancer (CRC)[10]. Exposure of colon-cancer cell lines (Caco-2 and HT-29 cell lines) to apigenin and EGCG from the nutritional supplement (Flavo-Natin®) leads to a significant inhibition of tumor cell proliferation in vitro (Figure 3).

Numerous in vitro studies elucidated the beneficial molecular biological effects of flavonoids among which the inhibition of the Wnt/β-cathenin and nuclear factor κB pathways, inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor expression by blocking phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/AKT signalling are the most important targets[11]. Moreover, studies with biological end points revealed that flavonoids can suppress neoangiogenesis and increase apoptosis resulting in anti-carcinogenic and anti-mutagenic effects[12].

Clinical studies such as cohort and case-control trials suggest that increasing dietary flavonoids can be associated with a lower incidence and prevalence of CRC and colon adenomas. EGCG, flavons and flavonols can prevent growth of early forms of neoplasia such as adenomatous polyps and could be used for biological prevention[13,14]. Flavonoid treatment of at risk patients has the potential for tumor suppression in the gastrointestinal tract, as was shown for post surgical patients with resected CRC[15]. Tertiary bioprevention with flavonoids seems to be an appropriate target for improving the outcome of CRC survivors. Beside epidemiological studies, we need controlled randomized clinical trials to answer the question of whether flavonoids are useful for neoplasia prevention. It is unlikely that flavonoids are capable of treating advanced forms of neoplasia.

There is a great interest in new approaches to prevent and inhibit cancers of the pancreas, the prostate gland and the urinary tract using flavonoids. Some evidence indicates that flavonoids could be a new way to suppress these types of cancer.

Flavonoids belong to the polyphenols and possess anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties. For this reason, they are strong candidates for a new treatment option for patients with chronic inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). In CD and UC there is a sustained over expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as well as an accumulation of chronically activated inflammatory cells like lymphocytes and macrophages. Flavonoids can inhibit inflammatory pathways in vitro and in animal experiments[16]. Clinical pilot trials with these agents should be performed to assess their clinical activities in CD and UC since these botanicals are without relevant side effects compared to biological agents currently in use.

There might be a deficiency of certain flavonoids in our food due to insufficient intake of fruits and vegetables, the methods of industrialized agriculture and the modes of nutritional preservation and storage. Particularly, chemically defined forms of enteral and parenteral nutrition are deficient in flavonoids and other polyphenols[17]. Deficiencies of these compounds and other plant agents could be responsible for derailing the healthy steady state within and outside exposed epithelial cells. Without certain secondary plant metabolites, the microenvironment is disturbed by exogenous and endogenous toxins leading to a proinflammatory and mutagenic milieu with ensuing DNA damage. Neoplastic cells can proliferate in a milieu with inflammatory cytokines, free oxygen species and other radicals. Flavonoids could act as protective agents and block this unfavourable environment by inhibition of mutagenic and carcinogenic pathways. Deprived of these stimuli, neoplastic cells could cease to proliferate. Instead of trying to destroy the neoplastic cells by chemotherapy, secondary plant metabolites such as flavonoids could possibly be used to stabilize the extracellular environment to prevent enhanced carcinogenic cell proliferation.

Plants have developed antioxidative mechanisms for their evolution and to maintain their health. Like vitamins, flavonoids could play an emerging role for human health, cancer prevention and well being.

The first challenge in the future will be to define degenerative diseases for which flavonoids might be useful. This concept could apply to intestinal neoplasia and chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, as well as to neurodegenerative and chronic cardiovascular disorders. The second challenge will be to develop specific flavonoid preparations to deliver these compounds to the target structures and their receptors. If this can be accomplished, it may be possible to use flavonoids as tools for prevention and treatment, much like the vitamins did in the past.

The in vitro cell proliferation data were analyzed using the “Methodenplattform” (http://www.methodenplattform.de) from the Institut of Nutritional Science (University of Giessen, Germany).

Peer reviewer: Seung Joon Baek, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, The University of Tennessee, 2407 River Drive, Rm A228, Knoxville, TN 37996, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:727-747. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Chun OK, Chung SJ, Song WO. Estimated dietary flavonoid intake and major food sources of U.S. adults. J Nutr. 2007;137:1244-1252. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Yang CS, Wang X, Lu G, Picinich SC. Cancer prevention by tea: animal studies, molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:429-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 925] [Cited by in RCA: 829] [Article Influence: 51.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hoensch H, Richling E, Kruis W, Kirch W. [Colorectal cancer prevention by flavonoids]. Med Klin (Munich). 2010;105:554-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | McShea A, Ramiro-Puig E, Munro SB, Casadesus G, Castell M, Smith MA. Clinical benefit and preservation of flavonols in dark chocolate manufacturing. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:630-641. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Gerhauser C. Cancer chemopreventive potential of apples, apple juice, and apple components. Planta Med. 2008;74:1608-1624. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kuntz S, Wenzel U, Daniel H. Comparative analysis of the effects of flavonoids on proliferation, cytotoxicity, and apoptosis in human colon cancer cell lines. Eur J Nutr. 1999;38:133-142. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Radtke J, Linseisen J, Wolfram G. Fasting plasma concentrations of selected flavonoids as markers of their ordinary dietary intake. Eur J Nutr. 2002;41:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hoensch HP, Kirch W. Potential role of flavonoids in the prevention of intestinal neoplasia: a review of their mode of action and their clinical perspectives. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005;35:187-195. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Pan MH, Lai CS, Wu JC, Ho CT. Molecular mechanisms for chemoprevention of colorectal cancer by natural dietary compounds. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:32-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rajamanickam S, Agarwal R. Natural products and colon cancer: current status and future prospects. Drug Dev Res. 2008;69:460-471. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Yang CS, Wang X. Green tea and cancer prevention. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62:931-937. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Shimizu M, Fukutomi Y, Ninomiya M, Nagura K, Kato T, Araki H, Suganuma M, Fujiki H, Moriwaki H. Green tea extracts for the prevention of metachronous colorectal adenomas: a pilot study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3020-3025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Boehm K, Borrelli F, Ernst E, Habacher G, Hung SK, Milazzo S, Horneber M. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) for the prevention of cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD005004. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hoensch H, Groh B, Edler L, Kirch W. Prospective cohort comparison of flavonoid treatment in patients with resected colorectal cancer to prevent recurrence. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2187-2193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |