INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a highly malignant, generally fatal neoplasm arising from hepatocytes. HCC accounts for over 80% of all primary liver cancers, which rank fourth among the organ-specific causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide[1]. Extrahepatic metastases are not rare at diagnosis of HCC[2] and the most frequent sites of extrahepatic metastases are lung, abdominal lymph node and bone[3,4]. A review of the literature involving the surgical pathology of 355 solitary metastases to the pancreas identified 5 isolated pancreatic metastases from HCC[5]. Of these, 2 cases showed synchronous metastases and 3 cases were found at autopsy[6]. To the best of our knowledge, solitary pancreatic metastasis of HCC, which developed after curative resection, has never been described previously.

A variety of malignant tumors have been shown to metastasize to the pancreas[7-9]. At autopsy, pancreatic metastases are common and the primary carcinoma is usually located in the lung or in the gastrointestinal tract. In contrast, isolated pancreatic metastases at the time of diagnosis are rare and only account for only 2% to 3% of solid tumors of the pancreas[10]. Most do not present before the end stage of various primary neoplasms. At least 40% of these isolated metastases are derived from renal cell carcinomas while common primary sites for the remainder include lung cancer, breast cancer, colon cancer, melanoma and sarcomas[8,10,11].

A minority of these metastases are identified by imaging at the time of diagnosis of the primary tumor, while the majority are diagnosed at follow-up, either because of routine imaging or because of the development of symptoms[8]. In renal cell carcinoma, the mean interval between nephrectomy and the diagnosis of an isolated pancreatic metastasis is approximately 9 years. Unfortunately, pancreatic metastases are difficult to differentiate from primary pancreatic neoplasms. In particular, there are similar clinical presentations and similar features on radiological imaging. In this article, we report a case of isolated metastasis of an HCC to the pancreas 28 mo after curative resection of HCC.

CASE REPORT

A 46-year-old man with a history of surgical resection of hepatitis B associated HCC presented with a pancreatic mass that was identified with contrast enhanced dynamic computed tomography (CT) at follow-up. Two years and 4 mo previous to follow up, he was treated with an extended left hemihepatectomy for a 16.5 cm × 9 cm-sized solitary HCC compressing the intrahepatic duct. The pathology report disclosed a grade III HCC with portal vein invasion, but the resection margin was free of tumor. No obvious bile duct invasion or intrahepatic micrometastasis was noted. The patient was diagnosed as T3N0M0 stage IIIA disease by AJCC and modified UICC stage. The patient recovered well and subsequently had a 3 mo follow-up examination including liver dynamic CT and a serum α-fetoprotein test. Although series examinations revealed no definite intrahepatic recurrence, liver dynamic CT showed an irregular mass in the tail of the pancreas that was associated with dilatation of the distal pancreatic duct (Figure 1A). With a contrast-enhanced scan, the mass projected into the splenic vein (arrow, Figure 1B). Liver dynamic CT and 18F-FDG-positron emission tomography (PET) showed no recurrence of the primary HCC in the remnant. On FDG-PET, there was hypermetabolic activity in the pancreatic mass. Endosonography (EUS) revealed a rounded, well-defined mass (5 cm in diameter) in the tail of the pancreas (Figure 2). EUS-guided fine needle aspirations revealed a poorly differentiated carcinoma with histological features consistent with his previous HCC (Figure 3). The lesion was successfully resected, and no other metastatic lesions have been found in follow-up. Gross specimen study showed a mass in the tail of the pancreas, invading the splenic vein (Figure 4A). Microscopic examination revealed metastatic HCC in the pancreas (Figure 4B).

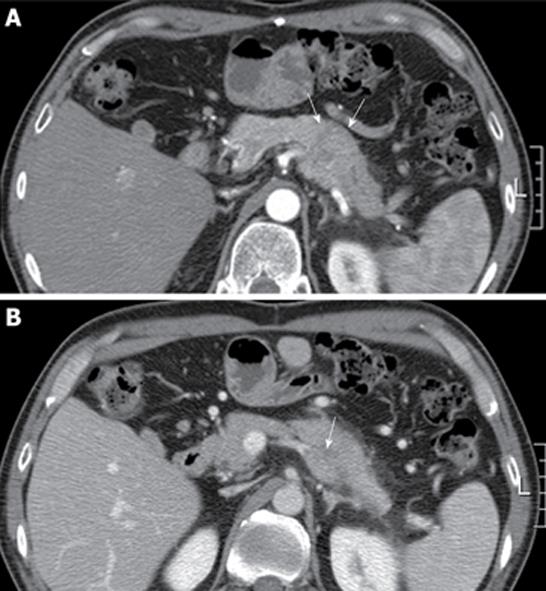

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography finding.

A: Computed tomography showed an irregular mass in the tail of the pancreas that was associated with dilatation of the distal pancreatic duct (arrow); B: With a contrast-enhanced scan, the mass projected into the splenic vein (arrow).

Figure 2 Linear endosonography (EUS) image revealing fine needle aspiration of a rounded, well-defined mass (5 cm in diameter) in tail of pancreas.

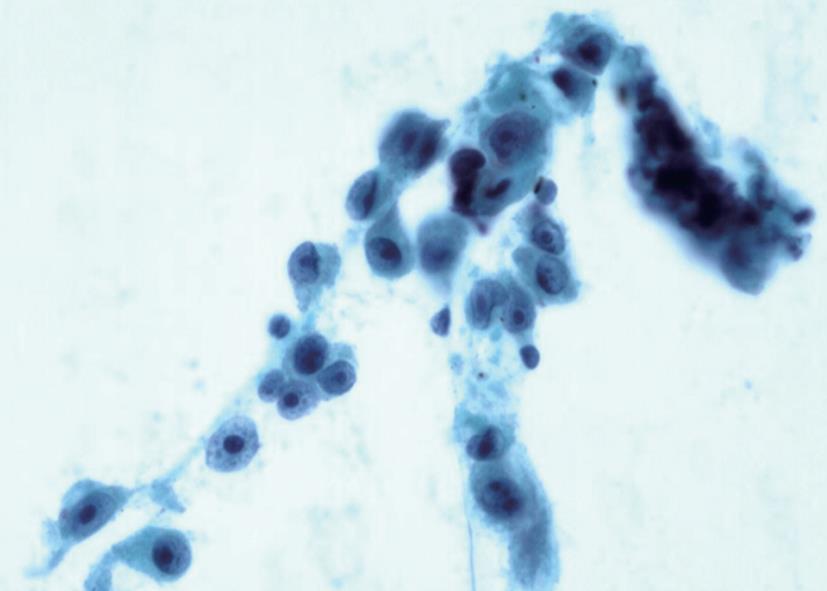

Figure 3 Photomicrograph of cytologic specimen obtained by EUS-guided showing a poorly differentiated carcinoma with histological features consistent with a metastasis from his previous hepatocellular carcinoma (Papanicolaou stain, × 200).

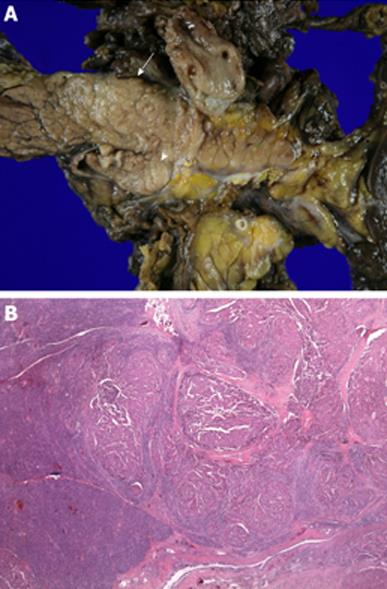

Figure 4 Surgical specimen.

A: The tumor was 4.5 cm × 3.4 cm × 2 cm in size in the tail of the pancreas (arrow) and invaded the splenic vein (arrow head); B: Microscopic examination revealed metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma in the pancreas (HE, × 40).

DISCUSSION

Differential diagnosis between a solitary pancreatic metastasis from a primary cancer and a double primary pancreatic cancer is difficult in almost all cases. The symptoms of metastases confined to the pancreas at the time of diagnosis are unspecific diagnostically, and imaging also rarely shows abnormalities seen only in primary neoplasms. This, together with the generally rare occurrence of solitary pancreatic metastases, explains why solitary pancreatic metastases are sometimes mistaken for primary tumors, particularly if there is a long interval from the resection of the underlying primary neoplasm. For differential diagnosis, solitary pancreatic metastases should be distinguished from primary neoplasms of the pancreas. Therefore, the diagnostic workup for tumors in the pancreas requires meticulous elaboration of the medical history.

The typical features of metastases from renal cell cancer detected by imaging studies (e.g. ultrasonography, CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and endoscopic ultrasonography) have been described repeatedly[12-15]. However, because these features are not confined to metastases from renal cell carcinoma, differentiation from other neoplasms of the pancreas is problematic in individual cases. Tissue diagnosis can be established before surgery with fine-needle aspiration biopsy, ultrasonography guided[16], CT guided[17], or endoscopic ultrasonography guided[18,19]. These techniques allow definitive tissue diagnosis, as well as an assessment of resectability. In the case of a pancreatic mass, rare causes, such as pancreatic metastasis, should also be taken into consideration besides the most common diagnosis, adenocarcinoma pancreas with its dismal prognosis. In particular, in cases where a patient is not undergoing surgical resection, a biopsy is mandatory to determine a definite diagnosis.

Surgical treatment of solitary pancreatic metastases from neoplasms other than renal cell cancer carries a poor prognosis, because they often signal the onset of disseminated metastatic disease[7,20]. Although resectable pancreatic metastasis is uncommon[7], metastatic pancreatic tumor from renal cell carcinoma is one of the favorable indications for radical surgery because it may offer a better prognosis for the patient[8,21,22]. Results of surgical extirpation of isolated metastases to the pancreas, not only from renal cell carcinoma but also from various primary tumors, provide improvement in long-term survival, revealing a clearly better prognosis than for primary pancreatic cancer[23,24]. This positive outcome suggests that solitary pancreatic metastases must not be regarded as accidental initial manifestations of impending diffuse metastatic disease and that a point must be made to correctly diagnose solitary pancreatic metastases and subject them to radical resection.

The result of treatment for extrahepatic recurrent HCC is poor[2,25,26]. Most metastases of HCC are multiple and are not amenable to surgical resection. Solitary metastases may be encountered occasionally. If considered resectable, the patient should be examined to exclude the presence of other metastasis, especially in the liver remnant, before embarking on surgery. Resection of isolated extrahepatic recurrences of HCC has been shown to prolong survival in selected patients[27-30]. The unusually positive outcome after treatment prompted a research group to question, rightfully, whether the positive outcome was really attributable to the successful removal of the metastases or whether it reflected an extremely protracted natural history of solitary pancreatic metastases.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of solitary pancreatic metastases of HCC that developed after curative resection. Our patient developed solitary pancreatic metastasis, which was documented 28 mo after resection of HCC. In patients with a pancreatic mass and history of HCC, the possibility of metastasis to the pancreas should also be taken into consideration besides the most common diagnosis, adenocarcinoma pancreas with its dismal prognosis.