Published online Dec 15, 2010. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i12.446

Revised: December 1, 2010

Accepted: December 8, 2010

Published online: December 15, 2010

Sarcomatoid carcinoma is a rare tumor with a poor prognosis, otherwise known as carcinosarcoma. Gastrointestinal origin is very rare and only a limited number of anal carcinosarcomas have been reported in the literature. The management of this rare cancer type is controversial. The aim of this case report was to confirm that by combining treatment modalities we can achieve long disease free intervals. Concomitant chemoradiotherapy led to a good partial response and this was followed by a consolidation surgical endo-anal excision.

- Citation: Mikropoulos C, Williams T, Munthali L, Summers J. A rare case of anal tumor: Anal carcinosarcoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2010; 2(12): 446-448

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v2/i12/446.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v2.i12.446

Anal carcinosarcomas are comprised of an epithelial component and a mesenchymal component. Histological examination reveals squamous cell carcinoma as well as spindle shaped sarcomatous elements. Kalogeropoulos et al[1] reported a case of a polypoidal spindle cell squamous carcinoma arising from the anus in 1985. The modern tools of immunohistochemistry were not available at the time and it was mainly the electron microscopy findings and the demonstration of keratin by an immunoperoxidase method that led to the diagnosis[1].

The mainstay of treatment remains surgery and adjuvant treatment has failed to offer any benefit[2]. A rare case of a successful treatment for an anal carcinosarcoma was published by Ozturk et al[3] in 2006. A 65 year old underwent an abdomino-perineal resection for an anal carcinosarcoma of the dentate line and had enjoyed a disease free survival of over 5 years. In the literature only a handful of colonic carcinosarcomas and even fewer anal carcinosarcomas have been reported[4].

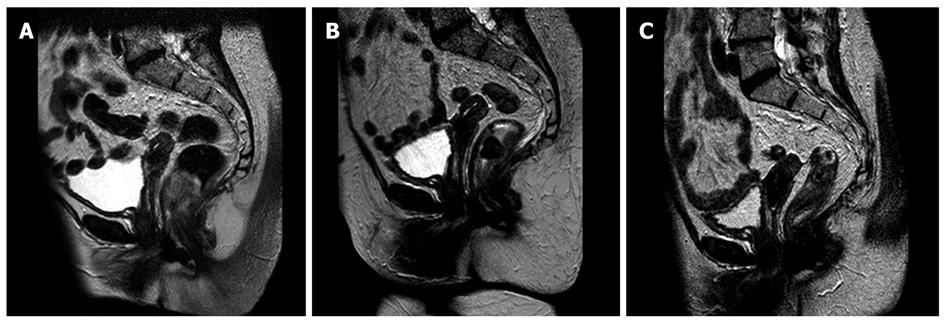

An 86-year-old patient presented with rectal bleeding, anaemia and weight loss on a background of diverticulosis. She was also passing mucus and had experienced a change in her bowel habit and was passing loose stools. Rigid sigmoidoscopy revealed a polypoidal very low rectal lesion on a narrow stalk. Examination under anaesthesia confirmed an unusually low left sided rectal polypoidal tumour arising in the transitional zone just above the dentate line. The tumour was mobile on the mucosa and had striking necrotic changes. The first biopsy of this bulky exophytic lesion failed to confirm malignancy. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the pelvis confirmed rectal wall invasion to over one third of the circumference of the rectum, extending beyond the rectal wall with ablated intersphincteric fat, with no mesorectal lymphadenopathy (T3N0) (Figure 1A). A computed tomography (CT) scan performed at the time showed 2 granulomatous lung lesions and failed to show any distant metastases.

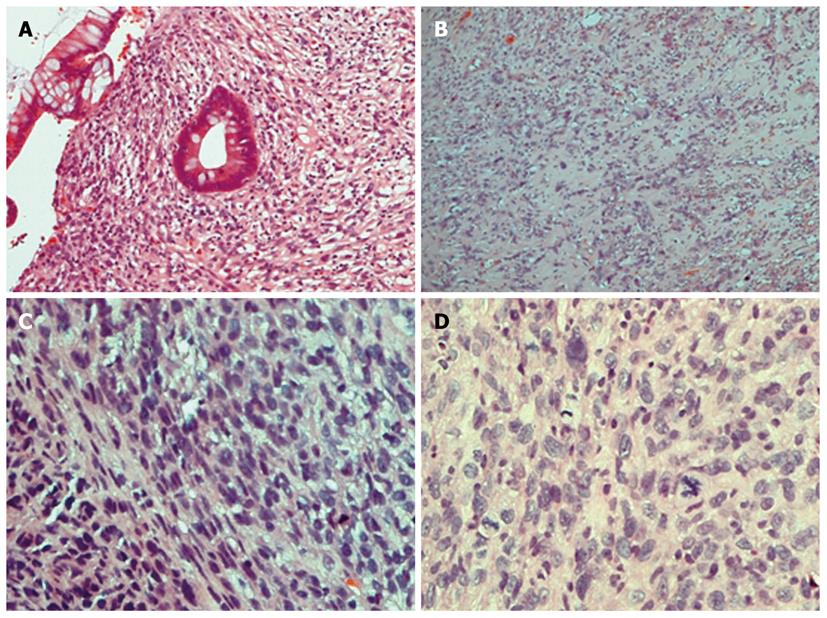

A repeat biopsy of the anal mass included squamous and glandular mucosa from the ano-rectal junction. There was severe dysplasia of the squamous mucosa with invasion. Marked florid spindle cell subepithelial proliferation was also noted. The immunohistochemical profile showed focal positivity for the pan-cytokeratin MNF116 as well as for SMA (α smooth muscle actin). The prevalent morphology was that of spindle cells with a high mitotic rate[5]. However, desmin staining was performed and was negative. Furthermore, C-Kit stain (CD-117) was negative which suggested this was not a GIST tumour. A negative S-100 stain excluded a melanocytic and neural lesions (Figure 2).

The patient underwent a defunctioning left iliac fossa colostomy prior to any other radical radiation treatment. She underwent treatment with chemoradiotherapy using conformal 3-dimensional planning with a four beam arrangement to a dose of 30.6 Gray in 17 fractions (1.8 Gray per fraction) to 100% of the ICRU reference point. Combination chemotherapy was given concomitantly with Mitomycin C 10 mg/m2 on day 1 followed by a 4 d of 5 Fluorouracil 750 mg/m2 as a 24 h infusion. Chemoradiotherapy was well tolerated with grade 2 skin erythema and desquamation, grade 1 fatigue and grade 1 diarrhoea, based on the NCI CTC criteria. Due to the patient’s age and performance status she was treated with a shortened radiotherapy treatment compared to the ACT protocol with only 30.6 out of 50.4 Gray administered and with the week 5 chemotherapy being omitted.

On an MRI scan performed 2 mo following completion of treatment a favourable response was reported with a reduction in size from 3 to 19 mm, but with a remaining suspicious area of rectal wall extension (T3) (Figure 1B). The patient then underwent an endo-anal excision of her residual lesion, which confirmed some residual sarcomatoid features with uncertain completeness of excision in view of fragmented tissue. Soon afterwards she had a reversal of the defunctioning stoma. An MRI scan 4 mo after excision showed no residual disease (Figure 1C). Sigmoidoscopy performed 6 mo later failed to show any evidence of tumour recurrence.

Further sigmoidoscopies and clinical examinations since then have failed to identify a recurrence. The patient is enjoying an excellent quality of life with no radiation late side-effects and she has now completed 2 disease free years.

Carcinosarcomas of the gastrointestinal tract commonly affect the oesophagus although there also are 40 reported cases in the gallbladder, 30 in the stomach and a small number at other sites. Only eight cases of colonic carcinosarcomas have been reported. The same treatment options that apply for the colonic adenocarcinoma are often used for colonic carcinosarcomas. Abdominoperineal resection is often performed followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The prognosis is very poor due to the aggressive nature of the rumour with a high risk of recurrence and distant spread[6]. A literature review by Tsekouras et al[7] indicated a median overall survival of 12 mo. Interestingly, early stage disease was not predictive of a favourable outcome[7].

Carcinosarcomas also arise in the oesophagus as bulky intraluminal polypoidal carcinomas with spindle-cell sarcomatous features. They give symptoms earlier and are diagnosed promptly leading to a more favourable prognosis. The diagnostic and therapeutic management does not vary from that for any other malignant oesophageal lesion[8]. Five year survival rates for oesophageal carcinosarcomas vary from 2% to 6%[9].

Based on the ACT trial results published in 1996, combined modality chemoradiation is recommended as first line treatment for all anal carcinoma patients, with salvage surgery reserved for those who fail on this regimen[10]. Patients are offered external beam radiotherapy using a parallel opposed pair in two phases with concomitant chemotherapy. In the first phase the fields are more generous in order to cover the nodes at risk to a dose of 30.6 Gray in 17 fractions prescribed to mid-separation. In the second phase the primary and the involved nodes are treated to a dose of 19.8 gray in 11 fractions. Concomitant chemotherapy consists of mitomycin and a four day 5FU infusion on weeks 1 and 5. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has not improved either loco-regional or distant control[11].

In the case described above the patient received treatment as for a typical anal squamous cell carcinoma with radical chemoradiotherapy. The total dose and treatment administration was different to the ACT protocol. Due to the patient’s age and comorbidities it was not possible to administer the full 50.4 Gray without compromising her quality of life. In order to prevent severe acute radiotherapy side-effects and aiming to preserve sphincter function we opted for treatment with just one phase using 3-dimensional planning. Only week 1 chemotherapy was administered, avoiding mitomycin-C induced myelotoxicity. Radiation and chemotherapy toxicities including skin erythema, moist desquamation, soreness and fatigue were non-severe and never worse than grade 2; no significant myelotoxicity was recorded. Despite a favourable response to initial treatment a complete response was not feasible and the patient required a salvage endo-anal excision for completion.

The disease free survival exceeded two years and there was a lack of late radiation side-effects with a good anal function and a favourable quality of life profile. Compared to published data this case sets a paradigm for managing anal carcinosarcoma and offering radical treatment with a curative intent.

Peer reviewers: Marius Raica, Professor, Department of Histology and Cytology, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Pta Eftimie Murgu 2, 300041, Timisoara, Romania; Carol Bernstein, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, College of Medicne, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85724-5044, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Kalogeropoulos NK, Antonakopoulos GN, Agapitos MB, Papacharalampous NX. Spindle cell carcinoma (pseudosarcoma) of the anus: a light, electron microscopic and immunocytochemical study of a case. Histopathology. 1985;9:987-994. |

| 2. | Conzo G, Giordano A, Candela G, Insabato L, Santini L. Colonic carcinosarcoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:748-749. |

| 3. | Oztürk E, Yilmazlar T, Yerci O. A rare tumor located in the anorectal junction: sarcomatoid carcinoma. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2006;17:236-239. |

| 4. | Hemmings CT, Frizelle FA. Carcinosarcoma of the anus: report of a case with immunohistochemical study and literature review. Pathology. 2006;38:264-267. |

| 5. | Wick MR, Swanson PE. Carcinosarcomas: current perspectives and an historical review of nosological concepts. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1993;10:118-127. |

| 6. | Takeyoshi I, Yoshida M, Ohwada S, Yamada T, Yanagisawa A, Morishita Y. Skin metastasis from the spindle cell component in rectal carcinosarcoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1611-1614. |

| 7. | Tsekouras DK, Katsaragakis S, Theodorou D, Kafiri G, Archontovasilis F, Giannopoulos P, Drimousis P, Bramis J. Rectal carcinosarcoma: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1481-1484. |

| 8. | Gaur DS, Kishore S, Saini S, Pathak VP. Carcinosarcoma of the oesophagus. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:e283-e285. |

| 9. | Hinderleider CD, Aguam AS, Wilder JR. Carcinosarcoma of the esophagus: a case report and review of the literature. Int Surg. 1979;64:13-19. |