INTRODUCTION

Peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) is a common evolution of cancer of the gastrointestinal tract (48% of gastric cancer with serosal erosion[1]). It has long been considered as the terminal stage of disease, and most oncologists have regarded it as a condition only to be treated with palliative care because most patients with carcinomatosis die within six months[2]. Since the 1980’s, a renewed interest in peritoneal surface malignancies developed through new multimodal therapeutic approaches. Cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has known an important development during the last 20 years, thanks to its favourable oncological results. However, it carries a significant morbidity and mortality, and it is time and resource consuming. Careful patient selection is required to improve outcomes and oncological results. Large multicenter studies have identified several prognostic factors that can be used for a better selection of patients who can benefit from the combination of cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC[3,4]. A consensus for those indications has been established within peritoneal surface malignancy treatment centers but has not been validated by prospective studies[5].

ORIGIN OF PERITONEAL CARCINOMATOSIS

Indications for the treatment of PC with cytoreduction and HIPEC are now validated for several diseases: peritoneal mesothelioma, pseudomyxoma peritonei, PC from appendix, and colorectal cancer.

In fact, it was demonstrated by several studies that long-term survival for peritoneal mesothelioma is higher with HIPEC and cytoreduction than with systemic chemotherapy[6-8].

Pseudomyxoma peritonei are also an excellent indication for HIPEC. In a large French multicenter study, including 277 patients treated by cytoreduction combined with HIPEC for pseudomyxoma peritonei, the median survival was not reach and higher than 100 mo[4]. The five and ten years overall survivals rates were respectively 73% and 55%.

The same study and others also reported survival rates for CP arising from adenocarcinoma of the appendix of up to 80% after five years[4,9,10].

The combination of cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC had demonstrated a survival benefit for the treatment of selected patients with resectable colorectal carcinomatosis in several prospective and retrospective studies, and in one randomised controlled trial. Two large multicenter registrations, including more than 500 patients, reported median survival of more than 30 mo and a 5-year survival rate of more than 30%[3,4]. Moreover, the long-term results of a randomised Dutch trial comparing HIPEC with mitomycin C and cytoreductive surgery to systemic chemotherapy alone (5-fluorouracil and leucovorin) for the treatment of carcinomatosis from colorectal origin, were recently reported[11]. The benefit of this combined procedure was clearly demonstrated (two-year survival rate of 43% in the HIPEC group versus 16% in the control, P = 0.014) and the trial was stopped for ethical reasons. This benefit was confirmed by the long-term results, which showed a 5-year survival rate of 45% for patients treated in the experimental arm.

In occidental countries, HIPEC is still in evaluation for gastric PC. Oncological results are limited, even if prolonged survival was reported in many series[12-14]. In Japan, several randomised trials have shown that HIPEC should be used to prevent PC in advanced gastric cancer[15]. These results have to be confirmed by an occidental randomised trial.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer might also benefit from the combination of cytoreduction and HIPEC. This kind of treatment is still under discussion for this indication. The usual indication is recurrent peritoneal carcinomatosis; however, indication at the first or second look might be considered and require more investigations in prospective trials.

According to their poor prognosis, mammary, pancreatic, biliary, or hepatic PC are contra-indications for HIPEC. HIPEC without cytoreduction might be considered eventually to treat refractory ascites for palliative treatment (drying up in 70% of cases[16]).

Due to a lack of large series for PC from sarcomatosis, endocrine or gastro-intestinal stromal tumor, no recommendations should be made. However, some authors report interesting results, and cytoreduction combined with HIPEC might be discussed in these cases as a therapeutic option for young people with a favourable health status.

HEALTH STATUS AND SYMPTOMS

Physiological age higher than 65 years, a World Health Organization (WHO) index more than two and severe medical history (severe cardio-pulmonary or renal failure) have to be considered as major contraindication[4,17].

Morbid obesity (BMI > 40), poor nutrition and intestinal obstruction are considered as minor contraindications. Intestinal obstruction is most often the sign of an extended PC and is described as a predictive factor for incomplete cytoreduction with poorer results than other patients[18,19]. However, in cases of bowel obstruction, surgery is often considered because systemic chemotherapy cannot be started. Averbach and Sugarbaker have evaluated the association of cytoreduction and early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for patients with recurrent intraabdominal malignancy causing intestinal obstruction[20]. They concluded that an aggressive treatment might be considered for palliation in these cases with acceptable morbidity and mortality (respectively 55% and 7.14%) and interesting oncological results (3-year survival was 32.7%). With nutritional care and medical treatment, these minor contraindications might disappear.

EXTENT OF DISEASE

Extraperitoneal metastasis

Extra-abdominal metastasis or massive retroperitoneal lymph nodes involvement are absolute contraindications[21,22]. Liver metastases are also a contraindication except for colorectal carcinomatosis. Several studies have shown that the presence of few (one to three) liver metastases did not influence survival if they could be surgically removed for PC from colorectal cancer[4,23,24]. For other origins, no results have been reported. Thus, no recommendations could made for PC in case of synchronous liver metastasis arising from non-colorectal cancer.

Extent of carcinomatosis and staging

The most important prognostic factor, whatever the origin of PC, is the completeness of cytoreduction (CCR)[25]. The residual disease after cytoreductive surgery is classified using the CCR score. CCR-0 indicates no visible residual tumor and CCR-1 indicates residual tumor nodules ≤ 2.5 mm. CCR-2 indicates residual tumor nodules between 2.5 mm and 2.5 cm. CCR-3 indicates a residual tumor > 2.5 cm. HIPEC is indicated when carcinomatosis is amenable to effective cytoreductive surgery allowing a CCR score ≤ 1. The probability of complete cytoreduction is correlated with the extent of PC.

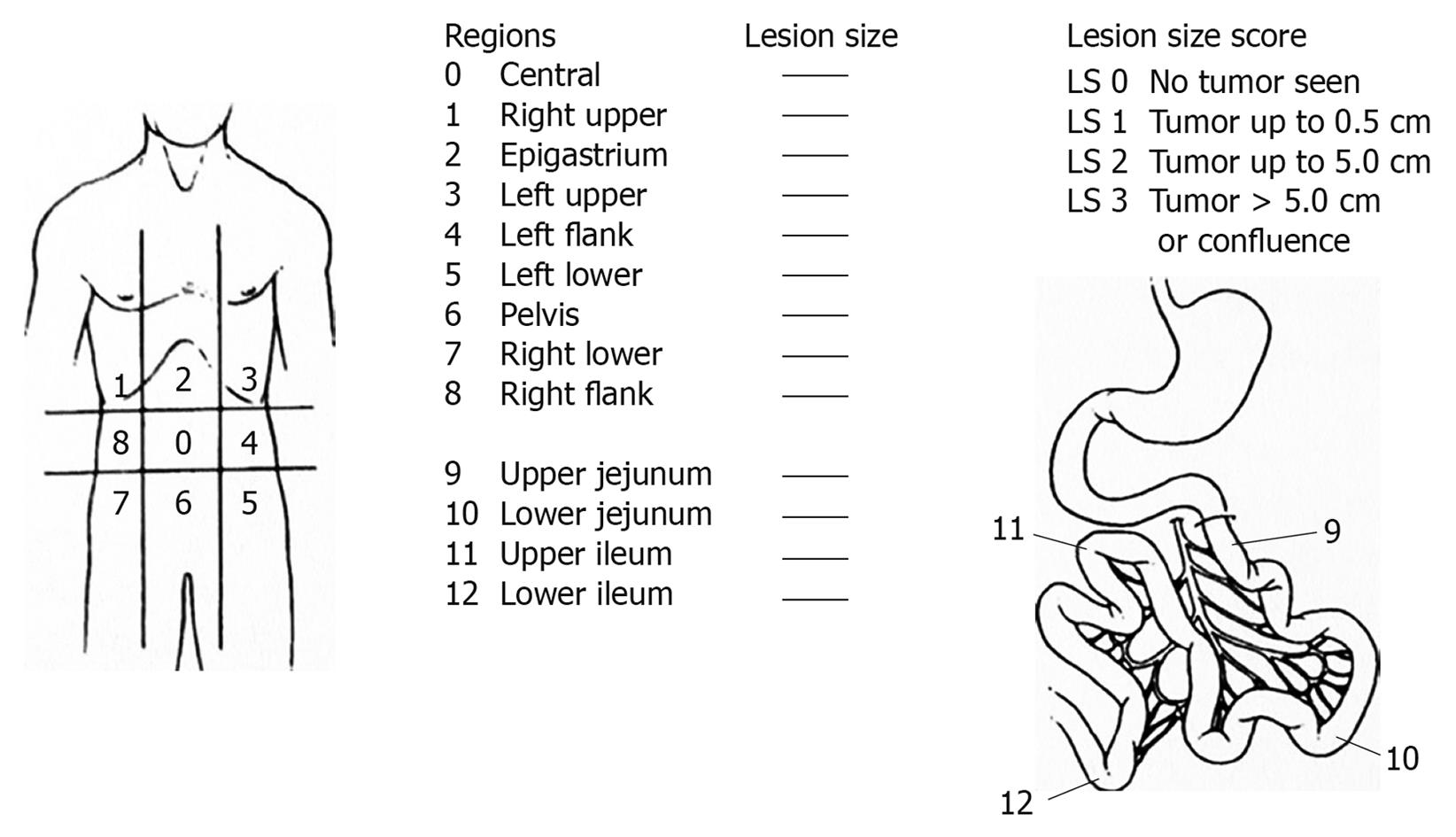

Thus, the extent of carcinomatosis represents one of the most important prognostic factors. It was the first factor investigated in a large multicenter trial of 1290 patients[4]. Several methods of classification have been used to investigate the extent of carcinomatosis. The Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) of Sugarbaker (Figure 1) was chosen by an expert panel as a useful quantitative prognostic tool[26]. It is a more precise assessment of carcinomatosis quantification and distribution. It was described by Jacquet and Sugarbaker[27]. It assesses the distribution and implant size of the cancer throughout the abdomen and the pelvis quantitatively. The abdomen and pelvis are divided by lines into nine regions (AR 0-8). The small bowel is then divided into four regions. Regions 9 and 10 define upper and lower portions of the jejunum, and regions 11 and 12 define the upper and lower portions of the ileum. The lesion size of the largest implant is scored as lesion size 0 through 3 (LS-0 to LS-3). LS-0 means no implants are seen throughout the regions. LS-1 refers to implants that are visible up to 0.5 cm in greatest diameter. LS-2 identifies nodules greater than 0.5 cm and up to 5 cm. LS-3 refers to implants 5 cm or greater in diameter. This measurement is made after a complete lysis of all adhesions and the complete inspection of all parietal and visceral peritoneal surfaces. This method quantifies the extent of the disease within each region of the abdomen and pelvis, and they can be summed as a numerical score (varying from 1 to 39) for the peritoneal cavity as a whole. This score allows an estimation of the probability of a complete cytoreduction. For colorectal carcinomatosis, Elias et al[28] reported that the survival results were significantly better when the PCI was lower than 16 than when 16 or higher. For Sugarbaker the limit should be 20, and colorectal carcinomatosis with a PCI of greater than 20 should be treated only palliatively. HIPEC is seldom indicated[29]. These limits vary with the origin of PC. For gastric carcinomatosis, some authors recommend limits of the indications for PC of PCI < 15 or < 10[30,31]. In patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei PCI > 20 is not an absolute exclusion criterion[32].

Figure 1 Peritoneal Cancer Index of Sugarbaker.

More than the quantity of PC, the distribution of PC in the abdomen constitutes the principal limitation for performing cytoreductive surgery. Massive involvement of the hepatic pedicle or ureteral obstruction are contraindications for cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC. The most frequent contraindication is a massive involvement of the small bowel or its mesentery, which involves a large sacrifice of the small bowel. Some clinical and radiographic variables have been associated with an increased probability of achieving a complete cytoreductive surgery in patients with PC from a colonic origin: no evidence of extra-abdominal disease, up to three small resectable parenchymal hepatic metastases, no evidence of biliary obstruction, no evidence of ureteral obstruction, no evidence of gross disease in the mesentery with several segmental sites of parietal obstruction, and small volume disease in gastro-hepatic ligament[30].

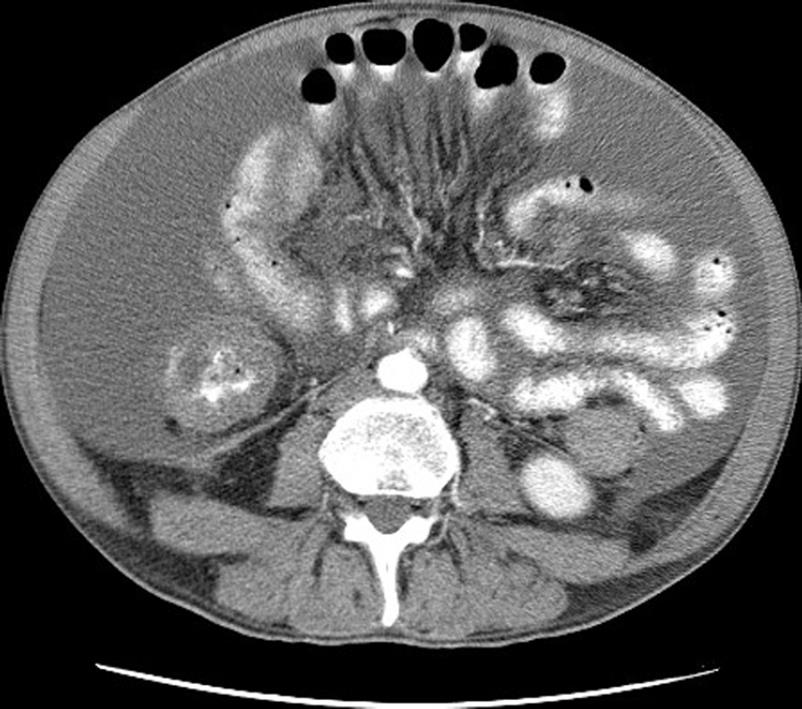

Contrast-enhanced multi-sliced computed tomography is a powerful instrument in the preoperative selection of patients for cytoreductive surgery. The Peritoneal Surface Malignancy Group considered that it is the fundamental imaging modality in preoperative selection[33]. It allows preoperative staging of PC, detection of retroperitoneal involvement, and detection of extra-abdominal metastasis. Studies correlating preoperative computed tomography findings with treatment outcome have been conducted in PC from peritoneal mesothelioma, colorectal, and appendiceal origin[19,34]. In these studies, it appeared to be possible to estimate the probability of complete cytoreduction with preoperative computed tomography. Yan et al[19] carried out a study in peritoneal mesothelioma. Two radiographic parameters were predictive for the completeness of cytoreductive surgery: the presence of a tumor > 5 cm in the epigastric region and the involvement of the small bowel and mesentery with nodular thickening, segmental obstruction and loss of mesenteric vessel clarity (Figure 2). When these two parameters were present, the probability of suboptimal cytoreduction was 100%, whereas when these two parameters were absent, the probability for complete cytoreduction was 94%. However, conclusions obtained in one type of malignancy should not be applied arbitrarily in another histology. Computed tomography is not able to detect all the contra-indications for cytoreductive surgery, notably it is unable to detect small nodules < 5 mm in the serosal surface of the small bowel. A carcinomatosis miliary on the small bowel is most often a contra-indication for cytoreductive surgery. Thus, computed tomography contributes greatly to one part of patient selection. However, surgical exploration is still necessary when no contra-indications are detected on the pre-operative exams. Unfortunately, in 20%-30% of cases, this surgical exploration finds lesions that are not amenable to complete cytoreduction. Laparoscopy has been proposed to improve preoperative carcinomatosis staging. It is associated with less pain, shorter hospitalisation and shorter recovery time in comparison to an exploration by laparotomy. Two studies demonstrated that it is possible to achieve full laparoscopic PCI assessment for a large majority of patients (96/97 in Valle’s study and 7/8 in Pomel’s study) with a few cases of carcinomatosis understaged (respectively 2/96 and 1/8)[35,36]. Despite these advantages, there are some limitations associated with laparoscopy. It is technically difficult to evaluate patients with intra-abdominal adhesions due to prior extensive abdominal surgery, and because of lymph node involvement in the retroperitoneal space. Another disadvantage of laparoscopic exploration is the risk of port track seeding. The international consensus made in 2006 in Milan did not recommended laparoscopic exploration as a routine investigational modality[33]. It was considered useful, as along with magnetic resonance imagery, in some specific cases. Positron emission tomography (PET) with 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) or preferably FDG-PET with computed tomography was also considered useful to detect extra-abdominal metastasis or to specify the nature of non-specific nodules (whether tumoral or not).

Figure 2 Contrast-enhanced computed tomography.

Typical mesenteric retraction with ascites.

EVOLUTION OF THE DISEASE

Except for pseudomyxoma peritonei and peritoneal mesothelioma, which are primitive carcinomatosis and frequently not sensitive to systemic chemotherapy, a progression of the PC during systemic chemotherapy should be considered as a contra-indication for cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC[37]. For young patients, who are assumed to have a limited and resectable PC, this rule may be discussed. A stabilization of the PC during systemic chemotherapy is equivalent to a positive response, and stabilization shouldn’t contra-indicate cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC. Finally, it is important to emphasize that ovarian metastases are considered intractable to systemic chemotherapy[38]. The evaluation of chemotherapy efficacy shouldn’t be done on the evolution of ovarian metastasis on radiographic examination.

MINIMAL PREOPERATIVE INVESTIGATIONS

The minimal preoperative investigations have to include: (1) physical examination; (2) cardiopulmonary investigation with cardiac echography and functional pulmonary exploration; (3) nephrological investigation: creatininemia and clearance of creatinine; (4) biologic evaluation of the hepatic function; (5) evaluation of nutrional state: body mass index, albuminemia and pro-albuminemia; and (6) extent of disease and staging: contrast-enhanced multi-sliced computed tomography, and if necessary FDG-PET, magnetic resonance imagery or laparoscopic exploration.