INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that there are over 1.9 million new cancer cases and 904000 of colorectal cancer deaths in 2022, representing nearly one in ten cancer cases and deaths[1]. Colorectal cancer ranks third among cancers worldwide in terms of incidence, and second in terms of mortality. The high incidence of colon cancer in developed countries is mainly due to a prevalence of risk factors such as obesity and an unhealthy diet[2]. Treatment of colon cancer mainly relies on the chemotherapeutic agent capecitabine. Remarkable progress has also been made in surgery, immunotherapy, stereotactic radiotherapy, and new chemotherapy drugs[3]. Early stage colon cancer patients can be treated by surgical resection. Unfortunately, due to the absence of distinctive clinical symptoms and inadequate colon cancer screening, a significant number of patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage[4]. Furthermore, many patients have already experienced local or distant spread at the time of diagnosis, the benefits of chemotherapy in relieving symptoms, prolonging progression free survival, and improving patients' quality of life are limited. Moreover, drug resistance, one of the main causes of chemotherapeutic failure, emerges in virtually all patients, resulting in a diminished therapeutic efficacy of anticancer agents[5]. Therefore, searching for novel drugs for the treatment of colon cancer is of utmost importance.

Tetramethylpyrazine (TMP), a component of the traditional Chinese medicine Chuanxiong Hort, has a long history of use in traditional Chinese medicine[6]. TMP is extensively utilized in treating neurovascular and cardiovascular conditions. Its potential mechanisms include the inhibition of platelet aggregation, peroxyl radical scavenging, and prevention of cell apoptosis, as well as interactions with superoxide and hydroxyl radicals[7,8]. Recent studies have demonstrated that TMP exhibits potent inhibitory effects on various types of tumors, including lung cancer, gastric cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, osteosarcoma, leukemia, and hepatocellular carcinoma, primarily through the inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and the promotion of apoptosis[9-13]. TMP can also reverse multidrug resistance on many types of tumors, such as bladder cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma[14,15]. We previously demonstrated that TMP inhibited the proliferation of colon cancer cells by inducing cell apoptosis and arresting the cell cycle at the G0/G1 phase[16]. However, the mechanisms of TMP-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells are not yet fully known.

Cell apoptosis, a highly regulated and controlled process, plays important roles in development, cell proliferation, and stress responses[17]. The two main apoptotic pathways are the death receptor-mediated pathway and mitochondria-mediated pathway; both pathways induce cell death by activating the caspase cascade[18]. Aberrant apoptosis results in uncontrolled cell proliferation and thus plays a key role in tumorigenesis[19]. Tumorigenesis is intricately associated with alterations in the expression of apoptotic genes and involves the activation of multiple apoptotic pathways[20].

Cancer cells have high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). However, excessive accumulation of ROS can exacerbate oxidative damage to cellular DNA and trigger apoptosis in cancer cells[21]. ROS are naturally occurring oxygenic reactive chemical compounds that emerge as by-products of cellular metabolism. They are pivotal in tumor biology, influencing various cellular processes and playing a significant role in cancer development and progression. The accumulation of intracellular ROS induces damage to proteins, enzymes, and organelle membranes, thereby activating apoptosis signaling pathways and leading to cancer cell death[22,23]. While oxidative stress is required for tumor growth, metastasis, and dissemination, an increase in basal oxidative stress also makes tumors more susceptible to the effects of chemotherapy drugs[24]. Therefore, increasing oxidative stress is now seen as an innovative and promising therapeutic strategy to selectively eliminate cancer cells.

In this study, we investigated the mechanism by which TMP induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Our data showed that TMP is an inducer of ROS in colon cancer cells, which activates the caspase cascade and induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Our research uncovered the mechanism of TMP-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells, and suggested that TMP may be a potential therapeutic option for colon cancer treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents

The human colon cancer cell lines HCT116 and SW480 were purchased from the Cell Resource Center of the Institute of Basic Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. The cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, United States) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone, United States) in a cell incubator with an atmosphere of 50 mL/L CO2 at 37 °C. TMP was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (United States) and dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, United States). Z-VAD-FMK was purchased from Med Chem Express (United States). N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) was purchased from Beyotime Institute (China). The Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) kit was purchased from BD (United States).

Morphological observation

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well) and cultured for 24 hours. Cells were treated with TMP at a final concentration of 600 µg/mL with or without Z-VAD-FMK and NAC for 12 hours. The cellular morphology was assessed under an inverted light microscope. Cell viability was determined through crystal violet staining. Briefly, cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well in 6-well plates and cultured for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with TMP for 48 hours, with cells treated with 0 µg/mL TMP serving as the control group. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated in crystal violet solution for 10 minutes. The morphology of the cells was re-examined under an inverted light microscope. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Cell apoptosis assay

Cells were incubated with TMP at a concentration of 600 µg/mL, with or without Z-VAD-FMK and NAC, for 12 hours. Subsequently, cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI for 30 minutes at 0 °C in the dark, following the manufacturer's protocol. The percentage of viable cells was quantified by flow cytometry. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Measurement of intracellular ROS

Intracellular ROS levels were quantified using the Oxygen Species Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates and allowed to adhere for 12 hours, followed by a 12-hour treatment with the specified agents. Subsequently, cells were incubated with DCFH-DA probes at 37 °C in a dark environment. The fluorescence intensity of DCF was quantified using flow cytometry (BD Bioscience, CA, United States).

Evaluation of caspase 3/9 activity

Caspase 3 and caspase 9 activities were assessed using assay kits (Beyotime Institute, Jiangsu, China) following the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates and incubated for 12 hours, followed by a 24-hour treatment with the designated agents. After treatment, cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were normalized prior to evaluating caspase activities following the kit instructions.

Western blot analysis

Cells were resuspended in Laemmli Buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, United States). Protein concentrations were quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pierce, United States). Equal amounts of protein were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, United States). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature.

Establishment of xenografts

Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Xingtai People’s Hospital. All surgical and animal care procedures were conducted following the NIH guidelines. Fifteen BALB/c nude male mice (18-22 g, 5-6 weeks old) were purchased from Vital River Laboratory (Beijing, China). The mice were assigned to three groups (n = 5 mice/group). Tumor xenografts were established by subcutaneously injecting 5 × 106 SW480 tumor cells into the right flanks of mice. Once the tumor xenografts became palpable, mice were given TMP (0, 50, or 100 mg/kg body weight) through oral gavage once every three days with careful administration. Tumor sizes were assessed every five days using digital calipers, and tumor volumes were calculated using the formula: Volume = 0.5 × length × width2. One month after the initiation of treatment, the mice were euthanized, and tumors were excised and weighed.

Malondialdehyde assay

The malondialdehyde (MDA) content in xenografts was determined using the MDA Assay Kit (Beyotime Technologies, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD from a minimum of three independent experiments. GraphPad Prism6 was used to perform statistical analyses and figure processing. The significance of difference was determined by one-way ANOVA with the least-significant difference test, and Student’s t-test was used for comparisons between two groups. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TMP-induced colon cancer cell apoptosis is mediated by accumulation of intracellular ROS

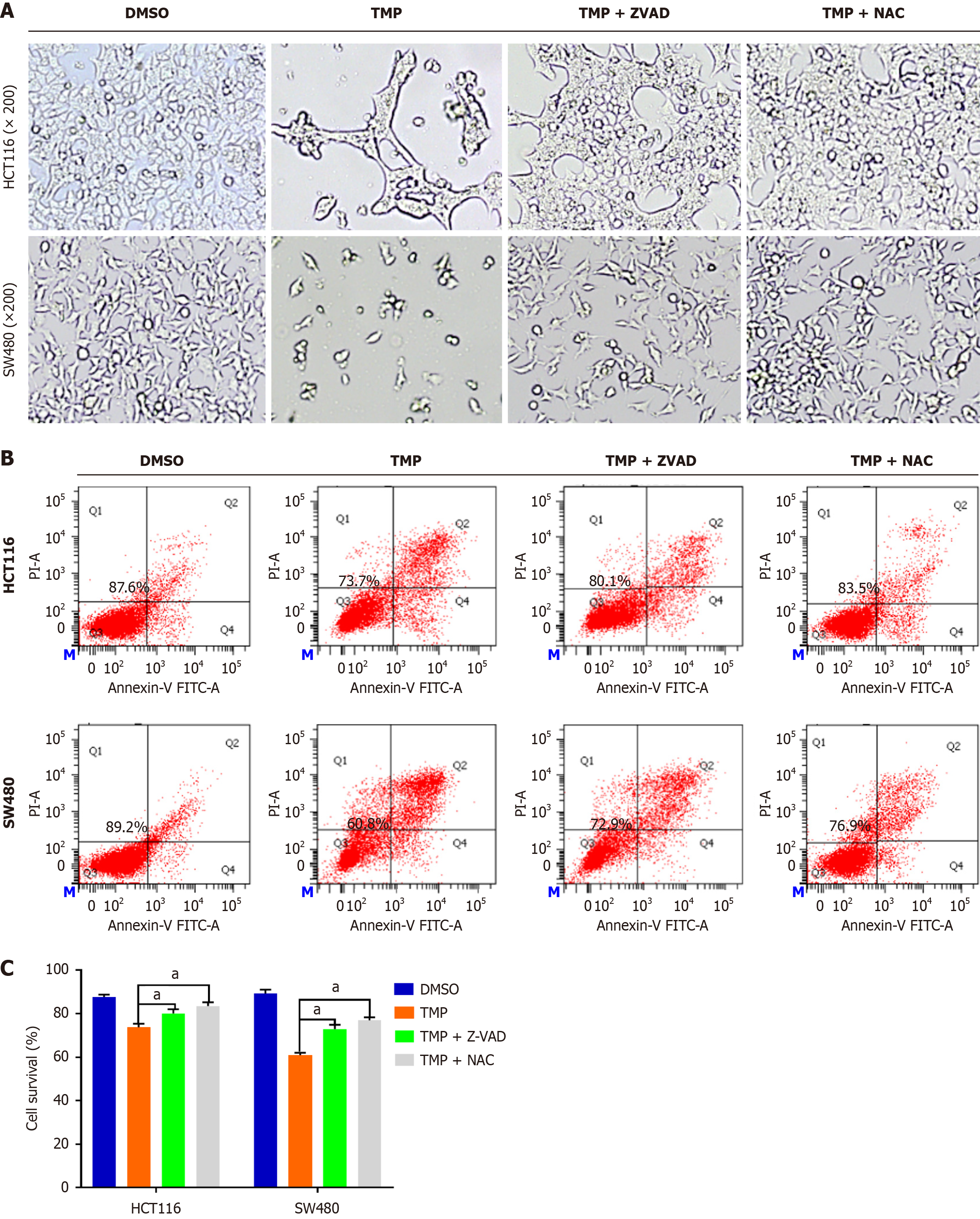

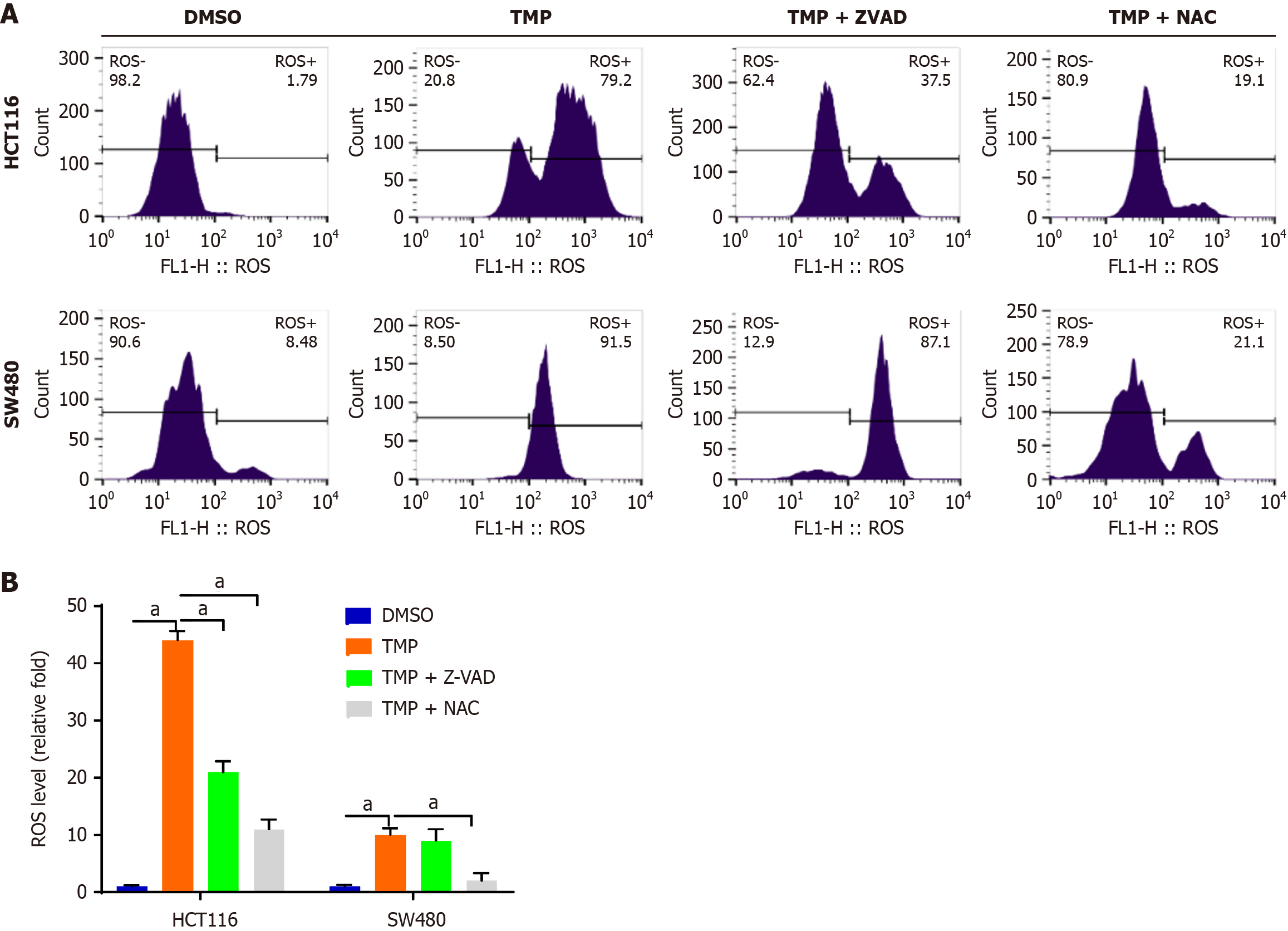

The generation of ROS closely correlates with tumor cell death. Intracellular ROS can be elevated as a result of abnormal metabolism and by drugs[25]. To examine the role of intracellular ROS in TMP-induced colon cancer cell death, we used the ROS scavenger NAC and the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK. Intracellular ROS convert non-fluorescing DCFH probes to fluorescent DCF probes, allowing for detecting them using flow cytometry. This process helps gain valuable insights into cellular oxidative stress. We found that NAC and Z-VAD-FMK inhibited TMP-induced cell apoptosis (Figure 1). The TMP group showed a significant reduction in cell numbers compared with the control group. Compared with the TMP group, the TMP + NAC and TMP + Z-VAD-FMK groups showed a significant increase in cell numbers. These results indicate that NAC and Z-VAD-FMK markedly reversed the killing effect of TMP on colon cancer cells. We subsequently assessed the production of ROS in HCT116 and SW480 cells following TMP treatment, and observed that TMP significantly elevated the levels of intracellular ROS in colon cancer cells (Figure 2). The antioxidant NAC inhibited the generation of ROS induced by TMP in both cell lines; ZVAD-FMK inhibited TMP-induced ROS production to a lesser degree in HCT116 cells and had no impact in SW480 cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 1 N-acetyl-L-cysteine and Z-VAD-FMK inhibit tetramethylpyrazine-induced cell apoptosis.

A: Cell morphology of SW480 and HCT116 cells treated with tetramethylpyrazine (TMP) with or without Z-VAD-FMK and N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) observed by inverted light microscopy; B: Percentage of apoptotic cells in SW480 and HCT116 cells treated with TMP with or without Z-VAD-FMK and NAC determined by flow cytometry; C: Cell survival rate of SW480 and HCT116 cells treated with TMP with or without Z-VAD-FMK and NAC. aP < 0.05. TMP: Tetramethylpyrazine; NAC: N-acetyl-L-cysteine.

Figure 2 N-acetyl-L-cysteine and Z-VAD-FMK inhibit tetramethylpyrazine-induced accumulation of intracellular reactive oxygen species.

A: Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) of SW480 and HCT116 cells treated with tetramethylpyrazine with or without Z-VAD-FMK and N-acetyl-L-cysteine detected by flow cytometry; B: Bar chart of intracellular ROS level in four groups of SW480 and HCT116 cells treated as indicated. aP < 0.001. TMP: Tetramethylpyrazine; NAC: N-acetyl-L-cysteine.

TMP-induced colon cancer cell apoptosis is mediated by mitochondria through ROS

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death and the mitochondrial apoptosis-induced pathway serves as an early indicator of apoptosis initiation[26]. Mitochondria occupy a pivotal position in the apoptotic pathway by supplying numerous critical factors, among which are those that trigger caspase activation and chromosome fragmentation[27]. The mitochondrial apoptosis signaling pathway is indispensable in the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells, as it is a key regulator of the cell death process. Mitochondria serve not only as the "energy factories" of cells, but also as central regulators of cellular survival and death. Dysfunction of mitochondria results in excessive ROS generation, which induces oxidative stress and further exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately leading to apoptosis[28]. ROS have been shown to promote mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis[29]. Our results showed that TMP may induce ROS and apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway.

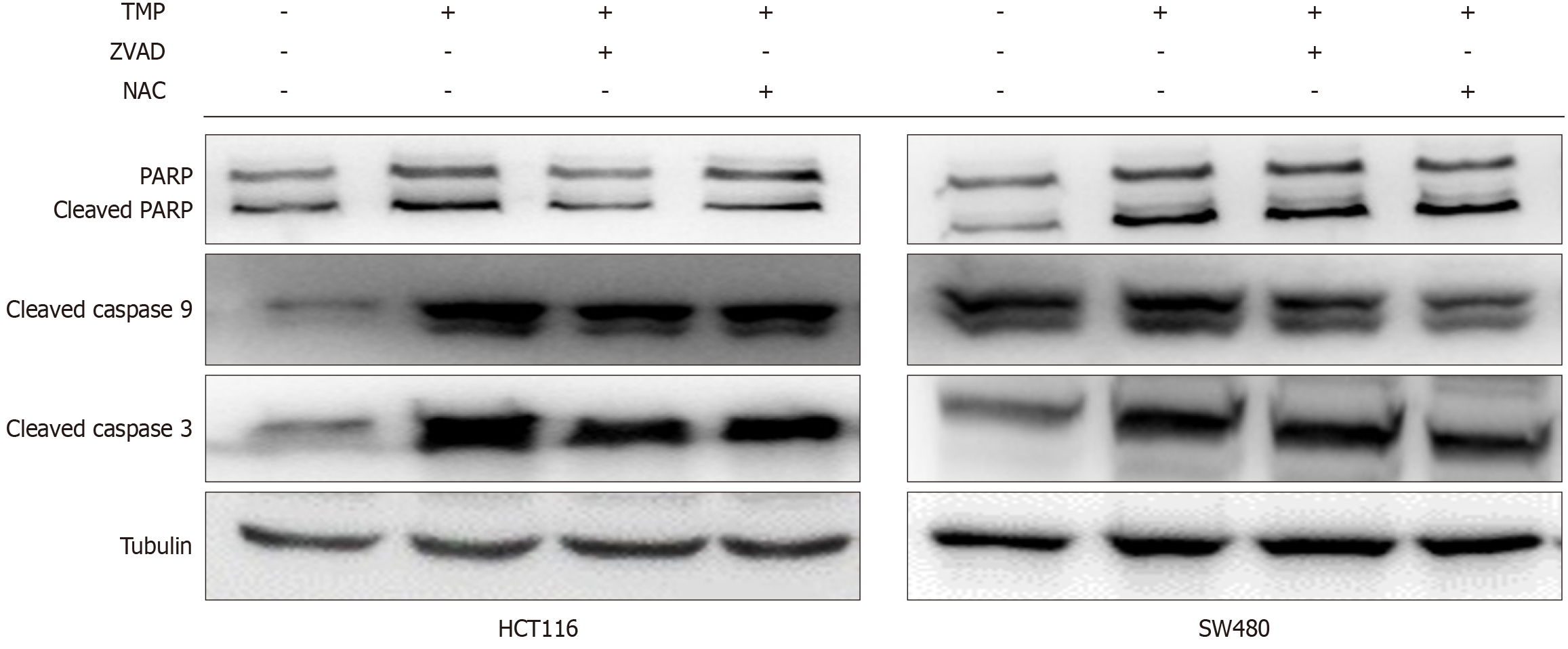

Western blot analysis showed increased cleaved caspase 3 and caspase 9 expression, markers of apoptosis, in both cell lines with the treatment of TMP (Figure 3). Caspase 3 and 9 cleavage induced by TMP was inhibited by NAC and Z-VAD-FMK. Additionally, the ROS scavenger NAC significantly inhibited TMP-induced activation and expression of caspases 3 and 9. However, the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK had reduced effects. These data suggested that TMP induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells via activation of the mitochondrial pathway through ROS.

Figure 3 Caspases 3 and 9 cleavage induced by tetramethylpyrazine is inhibited by N-acetyl-L-cysteine and Z-VAD-FMK.

Western blot analysis showed increased cleaved caspase 3 and caspase 9 expression in SW480 and HCT116 cells treated with tetramethylpyrazine with or without Z-VAD-FMK and N-acetyl-L-cysteine. TMP: Tetramethylpyrazine; NAC: N-acetyl-L-cysteine.

TMP inhibits tumor growth and induces apoptosis in xenograft models in vivo

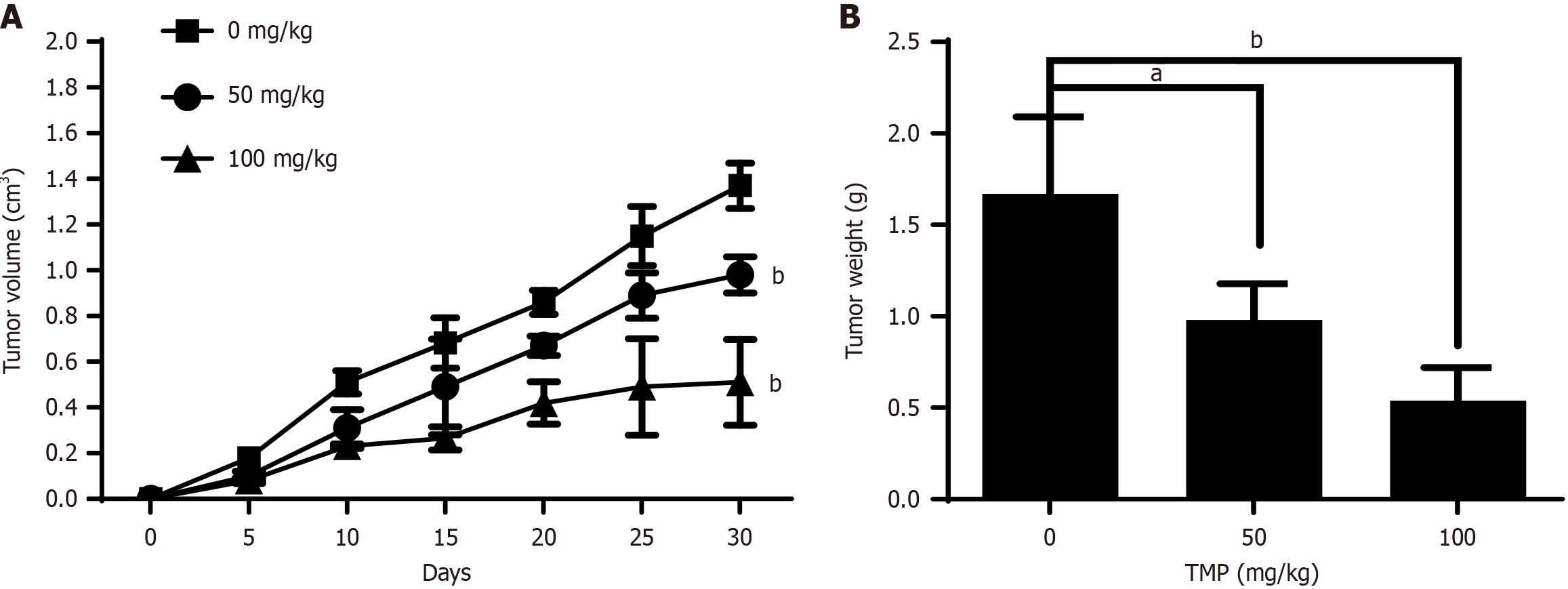

To evaluate the in vivo anticancer efficacy of TMP, we established xenograft models in immunodeficient mice by inoculating SW480 colon cancer cells. Cells were subcutaneously implanted into mice, and tumor-bearing mice were administered 50 or 100 mg/kg of TMP via gavage. Mice were monitored for 30 days. Tumor growth was effectively inhibited in both groups of mice treated with TMP compared with untreated model mice (Figure 4A). TMP also significantly reduced tumor weight (Figure 4B). These results demonstrated that TMP has a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on tumor growth in xenografts in mice.

Figure 4 Tetramethylpyrazine inhibits tumor growth in a xenograft mouse model.

A: Tumor volumes were calculated in mice treated with different concentrations of tetramethylpyrazine (TMP; 0, 50, and 100 mg/kg body weight) for 30 days (n = 5 mice/group); B: Tumor weight was calculated in mice treated with different concentrations of TMP (0, 50, and 100 mg/kg body weight) for 30 days (n = 5 mice/group). aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01. TMP: Tetramethylpyrazine.

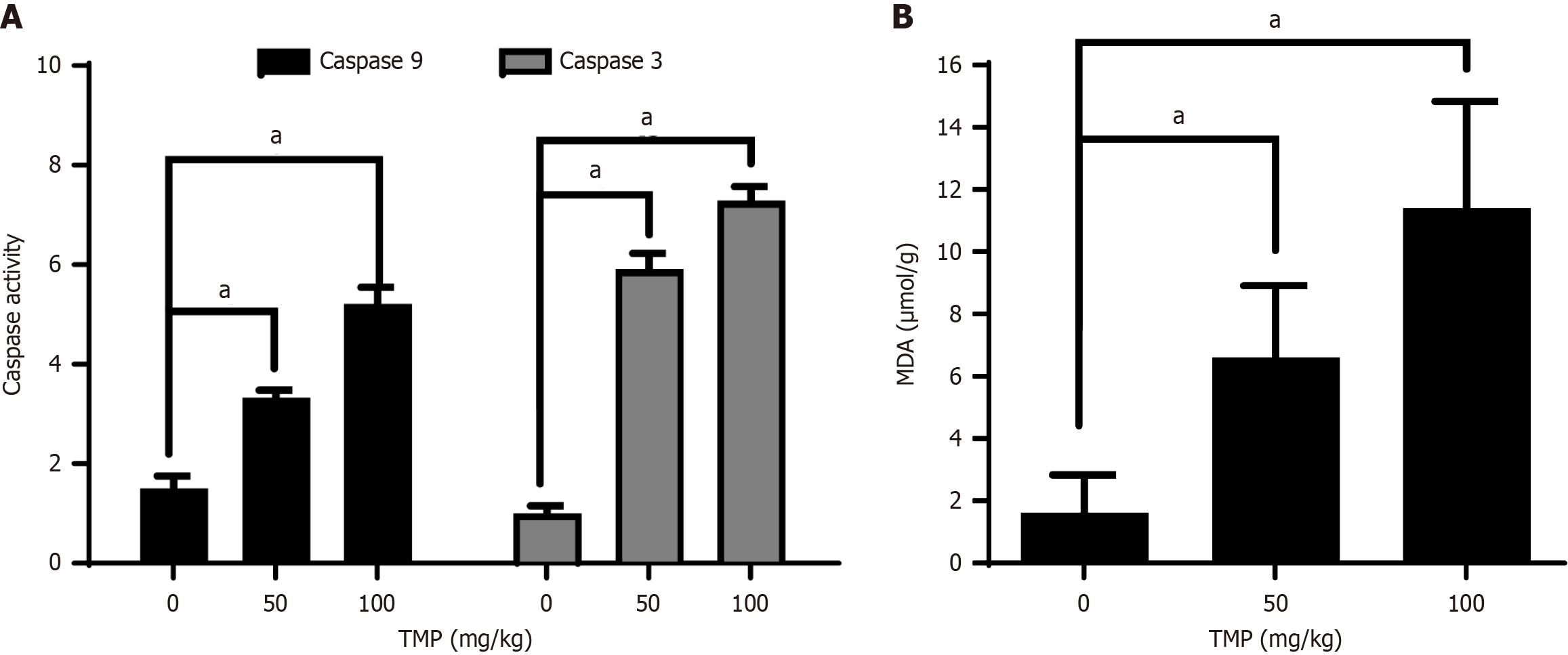

MDA is a key breakdown product of lipid peroxidation and serves as an important marker of oxidative damage. We found that MDA content in tumors increased in the groups treated with TMP (Figure 5A), suggesting that TMP increases oxidative stress and the generation of ROS in the mouse model. Increased caspases 3 and 9 activities were also detected in xenograft tumors of TMP-treated animals (Figure 5B), suggesting that TMP induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in vivo. These results suggested that TMP exhibits antitumor activities in vivo, with the accumulation of intracellular ROS in tumors.

Figure 5 Tetramethylpyrazine increases reactive oxygen species accumulation and induces apoptosis in xenograft tumors.

A: Malondialdehyde content in xenograft tumors increased with increasing tetramethylpyrazine (TMP); B: TMP treatment resulted in enhanced caspases 3 and 9 activities in xenograft tumors. aP < 0.01. TMP: Tetramethylpyrazine.

DISCUSSION

Cancer constitutes a significant societal, public health, and economic challenge in the 21st century, accounting for nearly one-sixth (16.8%) of global deaths and approximately one-quarter (22.8%) of fatalities due to noncommunicable diseases[1]. While surgery remains the primary curative treatment for colon cancer, chemotherapy continues to play a crucial role, given that many patients present with regional or distant metastases at the time of diagnosis[30]. Hence, searching for effective anti-tumor medicines has been a focus of research. The emergence of innovative therapeutic agents provides a promising alternative strategy to combat drug resistance in colon cancer. Plants have been identified as a rich source of anti-tumor compounds, and numerous plant-derived substances have been successfully utilized in clinical settings for cancer treatment, including vincristine, paclitaxel, and topotecan[31]. TMP is an alkaloid monomer present in the roots and stems from a Chinese herbal medicine plant and is considered to be safe because of its long history of use in Chinese traditional medicine. In addition to modulating the malignant biological behavior of tumor cells, TMP exhibits protective effects on adjacent non-tumor tissues. TMP can be synergistically used with chemotherapeutic agents to enhance tumor damage and mitigate their toxic side effects, including cardiac and renal toxicity[32]. In the present study, we found that TMP induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial-related pathway mediated by ROS.

We previously showed that TMP inhibited the proliferation of colon cancer cells. In this study, we first evaluated the production of ROS in colon cancer cells and found that TMP increased the generation of intracellular ROS. To identify the role of intracellular ROS in TMP-induced colon cancer cell death, the ROS scavenger NAC and the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK were used. The antioxidant NAC inhibited the generation of ROS induced by TMP in both cell lines; Z-VAD-FMK inhibited TMP-induced ROS production to a lesser degree in HCT116 cells and had no impact in SW480 cells. We found that NAC and Z-VAD-FMK inhibited TMP-induced cell apoptosis. This suggested that the cytotoxic effect of TMP on colon cancer cells was closely related to the production of ROS.

Apoptosis, an elegantly orchestrated form of programmed cell death, serves as a critical and indispensable mechanism in both physiological processes and pathological conditions[33]. Apoptosis mainly occurs through the mitochondrial-dependent (intrinsic) pathway and death receptor–dependent (extrinsic) pathway. The mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is one of the major apoptotic pathways[34]. Activation of both pathways involves the activation of a series of caspases. The extrinsic pathway is activated by cell surface death receptors, whereas the intrinsic pathway is triggered by formation of the cytosolic apoptosome composed of apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (Apaf-1), procaspase 9, and cytochrome c released from mitochondria[35]. Its release from the mitochondria initiates the formation of the apoptosome, a complex comprising Apaf-1, ATP, and procaspase-9, which activates the effectors caspase 3 and caspase 7, ultimately resulting in oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation[36]. In this study, Western blot analysis showed that caspases 3 and 9 cleavage increased with the treatment of TMP. The levels of cleaved caspases 3 and 9 induced by TMP treatment were inhibited by Z-VAD-FMK and NAC. These data suggested that TMP induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells through the activation of the mitochondrial pathway.

To further clarify the anticancer activities of TMP in vivo, we established xenograft models in immunodeficient mice. Mice treated with TMP showed a significant reduction in tumor weight. Moreover, TMP also enhanced caspases 3 and 9 activities in xenografts in vivo. MDA is a key byproduct of lipid peroxidation and serves as an important marker of oxidative damage. The MDA content in tumors increased with TMP treatment. These results suggested that TMP exerted antitumor effects in colon cancer in vivo and led to the accumulation of intracellular ROS in tumors.