Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.103629

Revised: January 9, 2025

Accepted: February 8, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 120 Days and 8.7 Hours

Oesophageal cancer is a significant health concern worldwide, with high inci

To explore the relationship between the mortality rate of oesophageal cancer patients and insurance type, out-of-pocket ratio, and the joint effects of insurance type and out-of-pocket ratio.

The χ2 test was used to analyze patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics. Multivariate logistic regression, the Cox proportional hazard model, and the competitive risk model were used to calculate the cumulative hazard ratios (HRs) of all-cause death and oesophageal cancer-specific death among patients with different types of insurance and out-of-pocket ratios.

Compared with patients covered by basic medical insurance for urban and rural residents, patients covered by urban employee basic medical insurance for urban workers (UEBMI) had a 23.30% increased risk of oesophageal cancer-specific death [HR = 1.233, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.093-1.391, P < 0.005]. Compared with patients in the low out-of-pocket ratio group, patients in the high out-of-pocket ratio group had a 25.80% reduction in the risk of oesophageal cancer-specific death (HR = 0.742, 95%CI: 0.6555-0.84, P < 0.005). With each 10% increase in the out-of-pocket ratio, the risk of oesophageal cancer-specific death decreased by 10.10% in patients covered by UEBMI. However, the risk of oesophageal cancer-specific death increased by 26.90% in patients in the high out-of-pocket ratio group.

This study reveals the relationships of the specific mortality rate of patients with oesophageal cancer with the out-of-pocket ratio and medical insurance types as well as their combined effects. This study provides practical suggestions and guidance for the formulation of relevant policies in this area.

Core Tip: The study reveals the intricate relationship between public health insurance, out-of-pocket payment ratios, and oesophageal cancer-specific mortality. It underscores the importance of insurance policy optimization to mitigate the mortality risk among high-risk groups and emphasizes the role of early intervention strategies in improving patient outcomes.

- Citation: Wu XL, Li XS, Cheng JH, Deng LX, Hu ZH, Qi J, Lei HK. Oesophageal cancer-specific mortality risk and public health insurance: Prospective cohort study from China. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(4): 103629

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i4/103629.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.103629

According to Global Cancer Statistics data, oesophageal cancer ranked eighth in incidence and sixth in mortality among all malignant tumours worldwide in 2020[1]. In the same year, China reported approximately 320000 new oesophageal cancer cases and 300000 oesophageal cancer-related deaths, accounting for 53.70% and 55.35% of the global figures, respectively. The burden of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) due to oesophageal cancer in China reached a staggering 5.76 million in 2019, accounting for 49.40% of the global burden. The age group with the highest DALYs was 65 to 69 years, reaching a total of 1.02 million person-years. This trend is consistent with the global distribution, high

Public health insurance, as a primary means of health care financing, contributes to sharing the disease risk of the entire population, but the effectiveness of risk sharing is influenced by a combination of patient demographic characteristics, clinical features, and medical insurance type. Therefore, studies on how to optimize the health care insurance system to reduce the mortality rate and economic burden of oesophageal cancer patients are particularly urgent. Most available studies on oesophageal cancer investigated the relationship between medical insurance and the economic burden on patients[2,6-8]. However, there is limited research on the relationship between medical insurance and patient prognosis[9,10]. This study is based on a prospective cohort study of oesophageal cancer patients in Chongqing, China, from July 1, 2018, to December 31, 2020, and it explores the relationships of the mortality rate of oesophageal cancer patients with insurance type and out-of-pocket ratio, as well as the joint effects of insurance type and the out-of-pocket ratio.

The data for this study were derived from the oesophageal cancer patient follow-up database at Chongqing University Cancer Hospital in China. Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, we conducted a selection process for all patients who entered the database between July 1, 2018 and December 31, 2020. A total of 2543 oesophageal cancer patients were included in the study, establishing a prospective cohort research sample. We gathered essential information on these patients, encompassing demographic characteristics (age at diagnosis, gender, marriage, nation, insurance type, medical expenses), clinical features (underlying diseases, pathological types, cancer staging), treatment modalities (surgery, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy), key biochemical indicators [body mass index (BMI), Karnofsky performance status (KPS), etc.], and follow-up information.

This study employed specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria encompassed individuals meeting the following conditions: (1) Being pathologically diagnosed with oesophageal cancer for the first time; (2) Completing primary treatment at the research hospital; and (3) Patients aged 18 years or older. Exclusion criteria involved the individuals meeting the following conditions: (1) Concomitant malignancies other than oesophageal cancer; (2) Incomplete treatment information; and (3) Lacked contact information or relevant data for follow-up and outcomes.

The follow-up period was measured in months and initiated from the time of the patient’s initial diagnosis of oesophageal cancer. It concluded either at the time of the patient’s death or on June 30, 2023, whichever came earlier. Follow-up procedures included both active clinic visits and passive telephone follow-ups. The primary cause of death was predominantly ascertained through medical records, supplemented by information provided by immediate family members.

Currently, the primary components of China’s basic public health insurance system include the urban employee basic medical insurance (UEBMI) for urban workers and the urban and rural resident basic medical insurance (URBMI) for urban and rural residents. Both insurance programs boast a coverage rate close to 100%, significantly alleviating the economic burden of cancer patients[5,11,12]. UEBMI funding mainly comes from contributions by employees and their employers, while URBMI funding primarily relies on contributions from unemployed residents and government subsidies. Due to the varying economic capacities of funding entities, UEBMI exhibits higher funding levels and reimbursement rates than URBMI. Consequently, patients are categorized into UEBMI and URBMI groups. In this study, total expenses refer to all costs incurred by patients from the initial diagnosis of oesophageal cancer to the completion of treatment. Out-of-pocket expenses denote the portion of total expenses paid by the patients themselves. The patient’s out-of-pocket ratio is influenced by various factors such as pathological type, cancer staging, treatment modality, insurance category, age, and occupation[13]. Patients are divided into two groups based on the median out-of-pocket ratio (60%): The low out-of-pocket ratio group (less than or equal to 60%) and the high out-of-pocket ratio group (greater than 60%).

Firstly, we conducted a descriptive analysis of patients’ data, representing count data using frequencies and percentages. We employed χ2 tests to analyze differences in other variables among patients with different insurance types and out-of-pocket ratio groups. Adjusted according to different variables, multivariate logistic regression was utilized to separately analyze the relationship between treatment modalities and insurance categories and out-of-pocket ratio groups.

Secondly, using the URBMI group as a reference, we employed Cox regression models[14] to calculate the hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for oesophageal cancer-specific mortality and all-cause mortality to compare the mortality risk of patients with different insurance types. The same model was applied to two patient groups based on out-of-pocket ratios, with the low out-of-pocket ratio group as the reference. Both models did not violate the proportional hazards assumption based on Schoenfeld residual tests. We also utilized a competing risks model to calculate and plot the cumulative risks of oesophageal cancer-specific and all-cause mortality.

Finally, to further explore the joint effects of insurance types and out-of-pocket ratios, we analyzed the association between a 10% increase in out-of-pocket ratio and the risk of oesophageal cancer-specific mortality and all-cause mortality. In model A, we adjusted for demographic and clinical characteristics, including age at diagnosis, gender, marriage, nation, BMI, KPS, underlying diseases, pathological type, and tumor node metastasis. In model B, based on model A, we further adjusted for treatment modalities, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, surgery, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy. In model C, building upon model B, we additionally adjusted for biochemical indicators (as potential mediators), including fibrinogen, β2-microglobulin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), platelet to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, albumin to globulin ratio (ALB/GLB) and cluster of differentiation (CD) 4/CD8. All analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 4.3.2), and a significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we ultimately included 2543 oesophageal cancer patients. The average age at diagnosis was 65.46 ± 8.57 years, with a predominance of males, married individuals, and Han nationality, accounting for 2088 (82.11%), 2381 (93.63%), and 2519 (99.06%) individuals, respectively. Among the included patients, 1871 (73.57%) were covered by URBMI, and 1450 (57.02%) had an out-of-pocket ratio of less than or equal to 60%. Among patients covered by URBMI, 1058 (56.55%) patients had an out-of-pocket ratio exceeding 60%, whereas among those covered by UEBMI, only 35 (5.21%) patients had an out-of-pocket ratio exceeding 60% (P < 0.001). The insurance groups were not significantly different in terms of age, marital status, nationality, pathological category, surgical status, LDH level, or CD4/CD8 ratio. In contrast, differences in other variables were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Except for surgery status, the ALB/GLB ratio, and the CD4/CD8 ratio, the differences among the different out-of-pocket ratio groups were consistent with those of the insurance categories. The detailed results are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | All (n = 2543) | By insurance type | By out-of-pocket ratio | ||||

| URBMI (n = 1871) | UEBMI (n = 672) | P value | ≤ 60% (n = 1450) | > 60% (n = 1093) | P value | ||

| Age | 65.46 ± 8.57 | 65.50 ± 8.21 | 65.36 ± 9.50 | 0.703 | 65.50 ± 9.07 | 65.41 ± 7.86 | 0.787 |

| Sex | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Male | 2088 (82.11) | 1465 (78.30) | 623 (92.71) | 1246 (85.93) | 842 (77.04) | ||

| Female | 455 (17.89) | 406 (21.70) | 49 (7.29) | 204 (14.07) | 251 (22.96) | ||

| Marriage | 0.245 | 0.498 | |||||

| Married | 2381 (93.63) | 1745 (93.27) | 636 (94.64) | 1353 (93.31) | 1028 (94.05) | ||

| Others | 162 (6.37) | 126 (6.73) | 36 (5.36) | 97 (6.69) | 65 (5.95) | ||

| Nation | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Han | 2519 (99.06) | 1853 (99.04) | 666 (99.11) | 1436 (99.03) | 1083 (99.09) | ||

| Other minority | 24 (0.94) | 18 (0.96) | 6 (0.89) | 14 (0.97) | 10 (0.91) | ||

| BMI | < 0.001 | 0.003 | |||||

| 18.5-23.9 | 1550 (60.95) | 1181 (63.12) | 369 (54.91) | 856 (59.03) | 694 (63.49) | ||

| ≥ 24 | 594 (23.36) | 424 (22.66) | 170 (25.30) | 336 (23.17) | 258 (23.60) | ||

| < 18.5 | 399 (15.69) | 266 (14.22) | 133 (19.79) | 258 (17.79) | 141 (12.90) | ||

| KPS | 83.68 ± 8.10 | 83.90 ± 7.74 | 83.06 ± 9.02 | 0.020 | 82.94 ± 8.44 | 84.66 ± 7.53 | < 0.001 |

| Base disease | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 2033 (79.94) | 1567 (83.75) | 466 (69.35) | 1109 (76.48) | 924 (84.54) | ||

| Yes | 510 (20.06) | 304 (16.25) | 206 (30.65) | 341 (23.52) | 169 (15.46) | ||

| Pathological | 0.297 | 0.365 | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2453 (96.46) | 1800 (96.21) | 653 (97.17) | 1394 (96.14) | 1059 (96.89) | ||

| Others | 90 (3.54) | 71 (3.79) | 19 (2.83) | 56 (3.86) | 34 (3.11) | ||

| TNM | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| I | 196 (7.71) | 156 (8.34) | 40 (5.95) | 66 (4.55) | 130 (11.89) | ||

| II | 634 (24.93) | 492 (26.30) | 142 (21.13) | 324 (22.34) | 310 (28.36) | ||

| III | 989 (38.89) | 734 (39.23) | 255 (37.95) | 584 (40.28) | 405 (37.05) | ||

| IV | 724 (28.47) | 489 (26.14) | 235 (34.97) | 476 (32.83) | 248 (22.69) | ||

| Radiotherapy | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 1554 (61.11) | 1214 (64.89) | 340 (50.60) | 627 (43.24) | 927 (84.81) | ||

| Yes | 989 (38.89) | 657 (35.11) | 332 (49.40) | 823 (56.76) | 166 (15.19) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 0.002 | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 1488 (58.51) | 1129 (60.34) | 359 (53.42) | 712 (49.10) | 776 (71.00) | ||

| Yes | 1055 (41.49) | 742 (39.66) | 313 (46.58) | 738 (50.90) | 317 (29.00) | ||

| Surgery | 0.732 | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 1365 (53.68) | 1000 (53.45) | 365 (54.32) | 852 (58.76) | 513 (46.94) | ||

| Yes | 1178 (46.32) | 871 (46.55) | 307 (45.68) | 598 (41.24) | 580 (53.06) | ||

| Immunotherapy | 0.000 | 0.027 | |||||

| No | 2332 (91.70) | 1740 (93.00) | 592 (88.10) | 1314 (90.62) | 1018 (93.14) | ||

| Yes | 211 (8.30) | 131 (7.00) | 80 (11.90) | 136 (9.38) | 75 (6.86) | ||

| Targeted | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 2450 (96.34) | 1827 (97.65) | 623 (92.71) | 1372 (94.62) | 1078 (98.63) | ||

| Yes | 93 (3.66) | 44 (2.35) | 49 (7.29) | 78 (5.38) | 15 (1.37) | ||

| FIB | < 0.001 | 0.006 | |||||

| ≤ 3.66 | 1635 (64.29) | 1265 (67.61) | 370 (55.06) | 899 (62.00) | 736 (67.34) | ||

| > 3.66 | 908 (35.71) | 606 (32.39) | 302 (44.94) | 551 (38.00) | 357 (32.66) | ||

| β2 microglobulin | 0.000 | 0.032 | |||||

| ≤ 3.62 | 2246 (88.32) | 1679 (89.74) | 567 (84.38) | 1263 (87.10) | 983 (89.94) | ||

| > 3.62 | 297 (11.68) | 192 (10.26) | 105 (15.62) | 187 (12.90) | 110 (10.06) | ||

| LDH | 0.260 | 0.280 | |||||

| ≤ 236.4 | 2228 (87.61) | 1648 (88.08) | 580 (86.31) | 1261 (86.97) | 967 (88.47) | ||

| > 236.4 | 315 (12.39) | 223 (11.92) | 92 (13.69) | 189 (13.03) | 126 (11.53) | ||

| PLR | 0.022 | 0.024 | |||||

| ≤ 222.22 | 2082 (81.87) | 1552 (82.95) | 530 (78.87) | 1165 (80.34) | 917 (83.90) | ||

| > 222.22 | 461 (18.13) | 319 (17.05) | 142 (21.13) | 285 (19.66) | 176 (16.10) | ||

| LMR | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| ≤ 3.18 | 1181 (46.44) | 812 (43.40) | 369 (54.91) | 718 (49.52) | 463 (42.36) | ||

| > 3.18 | 1362 (53.56) | 1059 (56.60) | 303 (45.09) | 732 (50.48) | 630 (57.64) | ||

| NLR | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| ≤ 5.28 | 2178 (85.65) | 1647 (88.03) | 531 (79.02) | 1201 (82.83) | 977 (89.39) | ||

| > 5.28 | 365 (14.35) | 224 (11.97) | 141 (20.98) | 249 (17.17) | 116 (10.61) | ||

| ALB/GLB | 0.006 | 0.171 | |||||

| ≤ 1.08 | 436 (17.15) | 297 (15.87) | 139 (20.68) | 262 (18.07) | 174 (15.92) | ||

| > 1.08 | 2107 (82.85) | 1574 (84.13) | 533 (79.32) | 1188 (81.93) | 919 (84.08) | ||

| CD4/CD8 | 0.394 | < 0.001 | |||||

| ≤ 1.78 | 1484 (58.36) | 1082 (57.83) | 402 (59.82) | 899 (62.00) | 585 (53.52) | ||

| > 1.78 | 1059 (41.64) | 789 (42.17) | 270 (40.18) | 551 (38.00) | 508 (46.48) | ||

We analyzed the effect of insurance type and the out-of-pocket ratio on the treatment choices of oesophageal cancer patients, considering treatment modality as the dependent variable and insurance type and the out-of-pocket ratio as independent variables. After adjusting for age, sex, marital status, nationality, pathological diagnosis, cancer stage, and biochemical indicators, patients covered by UEBMI were significantly more likely to choose radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy than patients covered by the URBMI (P < 0.05). Patients in the high out-of-pocket ratio group were less likely to choose radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy than those in the low out-of-pocket ratio group. Instead, they were more likely to choose surgical treatment, and these differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The detailed results are presented in Table 2.

| Variables | n (%) | 1Model A | 2Model B | 3Model C | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Radiotherapy | |||||||

| Insurance type | |||||||

| URBMI | 657 (35.11) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| UEBMI | 332 (49.4) | 1.874 (1.561-2.25) | < 0.001 | 1.823 (1.509-2.203) | < 0.001 | 1.949 (1.606-2.365) | < 0.001 |

| Out-of-pocket ratio | |||||||

| ≤ 60% | 823 (56.76) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 60% | 166 (15.19) | 0.124 (0.101-0.152) | < 0.001 | 0.124 (0.101-0.152) | < 0.001 | 0.118 (0.096-0.146) | < 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | |||||||

| Insurance type | |||||||

| URBMI | 131 (7.00) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| UEBMI | 80 (11.90) | 1.375 (1.139-1.659) | 0.001 | 1.283 (1.052-1.566) | 0.014 | 1.333 (1.089-1.632) | 0.005 |

| Out-of-pocket ratio | |||||||

| ≤ 60% | 136 (9.38) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 60% | 75 (6.86) | 0.351 (0.294-0.418) | < 0.001 | 0.363 (0.302-0.437) | < 0.001 | 0.351 (0.291-0.423) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery | |||||||

| Insurance type | |||||||

| URBMI | 742 (39.66) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| UEBMI | 313 (46.58) | 0.977 (0.813-1.173) | 0.800 | 1.075 (0.881-1.312) | 0.478 | 1.106 (0.904-1.354) | 0.329 |

| Out-of-pocket ratio | |||||||

| ≤ 60% | 738 (50.9) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 60% | 317 (29) | 1.599 (1.36-1.88) | < 0.001 | 1.351 (1.134-1.609) | 0.001 | 1.344 (1.126-1.603) | 0.001 |

| Immunotherapy | |||||||

| Insurance type | |||||||

| URBMI | 871 (46.55) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| UEBMI | 307 (45.68) | 1.889 (1.396-2.556) | < 0.001 | 1.763 (1.292-2.406) | < 0.001 | 1.755 (1.281-2.403) | < 0.001 |

| Out-of-pocket ratio | |||||||

| ≤ 60% | 598 (41.24) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 60% | 580 (53.06) | 0.683 (0.507-0.92) | 0.012 | 0.729 (0.538-0.989) | 0.042 | 0.699 (0.514-0.951) | 0.023 |

| Targeted | |||||||

| Insurance type | |||||||

| URBMI | 131 (7) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| UEBMI | 80 (11.9) | 3.702 (2.393-5.727) | < 0.001 | 3.525 (2.253-5.515) | < 0.001 | 3.857 (2.443-6.089) | < 0.001 |

| Out-of-pocket ratio | |||||||

| ≤ 60% | 136 (9.38) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 60% | 75 (6.86) | 0.224 (0.127-0.394) | < 0.001 | 0.229 (0.129-0.407) | < 0.001 | 0.215 (0.12-0.385) | < 0.001 |

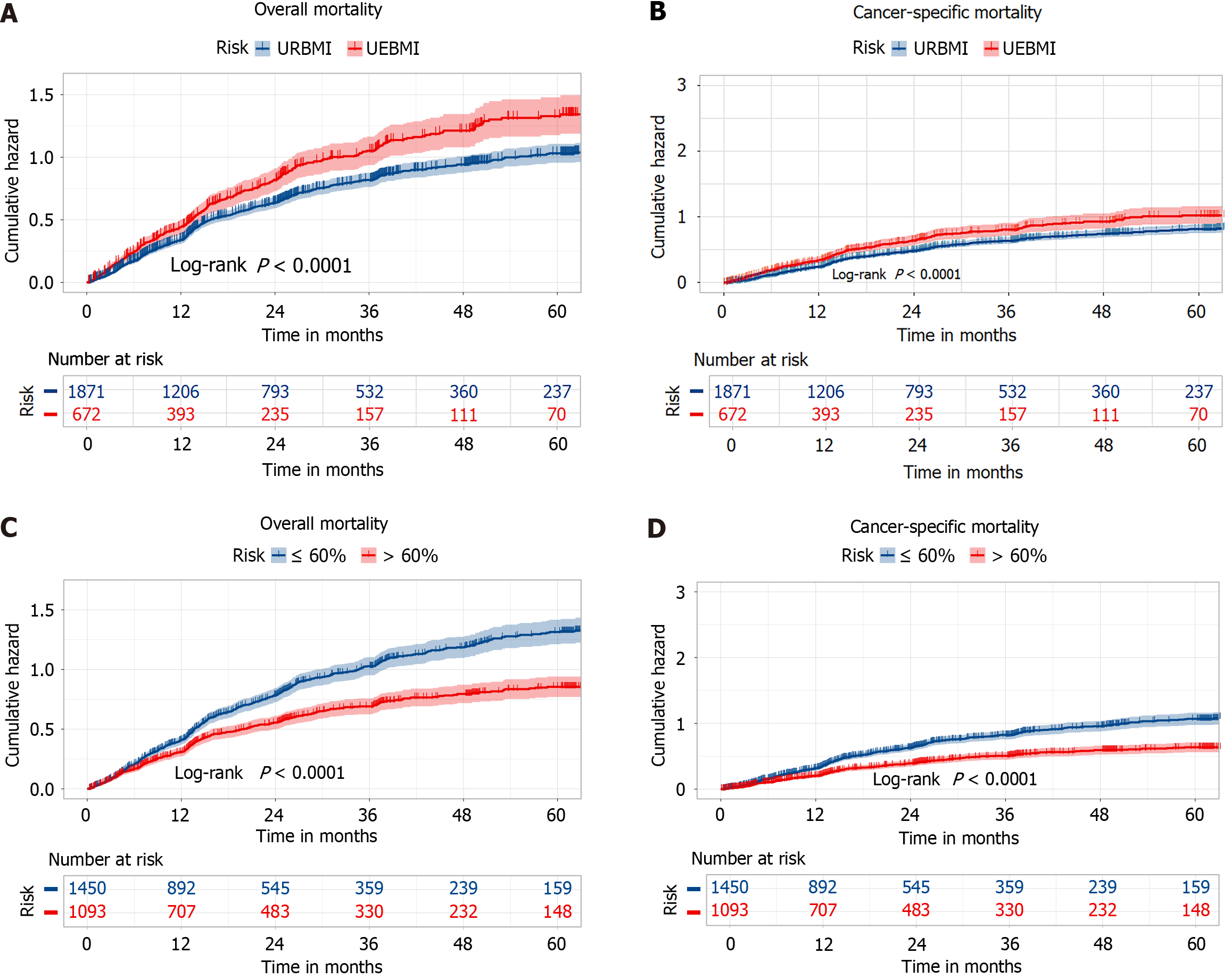

During the follow-up period (median: 48.50 months, interquartile range: 22.39-26.41 months), a total of 1438 deaths were observed, with 1106 attributed to oesophageal cancer. The patients covered by UEBMI had a higher cumulative risk of oesophageal cancer-specific mortality compared to those covered by URBMI. Similarly, patients in the low out-of-pocket ratio group had a higher cumulative risk of oesophageal cancer-specific mortality compared to those in the high out-of-pocket ratio group. The risk patterns for all-cause mortality were consistent with those for oesophageal cancer-specific mortality. The detailed results are shown in Figure 1.

After adjusting for demographic characteristics, clinical features, treatment modalities, and biochemical indicators, the risk of oesophageal cancer-specific mortality increased by 23.30% (HR = 1.233, 95%CI: 1.093-1.391), and the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 22.30% (HR = 1.233, 95%CI: 1.066-1.402, P < 0.005) for UEBMI patients compared to URBMI patients. The patients in the high out-of-pocket ratio group had a 25.80% decreased risk of oesophageal cancer-specific mortality (HR = 0.742, 95%CI: 0.655-0.840, P < 0.005) and a 33.20% decreased risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 0.668, 95%CI: 0.579-0.772) compared to those in the low out-of-pocket ratio group. Detailed results are presented in Table 3.

| Variables | Patients (n) | Events (n) | Rate | 1Model A | 2Model B | 3Model C | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | ||||

| Overall mortality | |||||||||

| Insurance type | 2543 | 1438 | 13.46 | ||||||

| URBMI | 1871 | 1012 | 13.24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| UEBMI | 672 | 426 | 17.43 | 1.199 (1.066-1.348) | 0.002 | 1.29 (1.145-1.453) | < 0.001 | 1.233 (1.093-1.391) | 0.001 |

| Out-of-pocket ratio | |||||||||

| ≤ 60% | 1450 | 924 | 17.50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 60% | 1093 | 514 | 10.13 | 0.85 (0.761-0.95) | 0.004 | 0.715 (0.632-0.809) | < 0.001 | 0.742 (0.655-0.84) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer-specific mortality | |||||||||

| Insurance type | 2543 | 1106 | 8.64 | ||||||

| URBMI | 1871 | 776 | 8.63 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| UEBMI | 672 | 330 | 10.74 | 1.218 (1.066-1.392) | 0.004 | 1.285 (1.122-1.472) | < 0.001 | 1.223 (1.066-1.402) | 0.004 |

| Out-of-pocket ratio | |||||||||

| ≤ 60% | 1450 | 741 | 11.74 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 60% | 1093 | 365 | 6.01 | 0.747 (0.657-0.850) | < 0.001 | 0.649 (0.562-0.748) | < 0.001 | 0.668 (0.579-0.772) | < 0.001 |

In analyzing the combined effects of insurance types and out-of-pocket ratios, we sequentially adjusted for patient demographics and clinical characteristics, treatment modalities, and biochemical indicators. Without grouping, for every 10% increase in the out-of-pocket ratio, the oesophageal cancer-specific mortality risk for all patients decreased by 5.30% (HR = 0.947, 95%CI: 0.915-0.980, P < 0.05), and all-cause mortality risk decreased by 4.50% (HR = 0.955, 95%CI: 0.927-0.984, P < 0.05).

After grouping by insurance type, for every 10% increase in the out-of-pocket ratio, patients covered by UEBMI experienced a 10.10% decrease in oesophageal cancer-specific mortality risk (HR = 0.899, 95%CI: 0.825-0.981, P < 0.05) and an 8.40% decrease in all-cause mortality risk (HR = 0.916, 95%CI: 0.849-0.988, P < 0.05).

While grouping by out-of-pocket ratio groups, for every 10% increase in out-of-pocket ratio, patients in the high out-of-pocket ratio group saw a 26.90% increase in oesophageal cancer-specific mortality risk (HR = 1.269, 95%CI: 1.087-1.481, P < 0.05) and a 17.40% increase in all-cause mortality risk (HR = 1.174, 95%CI: 1.026-1.342, P < 0.05). Detailed results are presented in Table 4.

| Variables | Patients (n) | Events (n) | Rate | 1Model A | 2Model B | 3Model C | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | ||||

| Overall mortality | |||||||||

| Any type per 10% increase | 2543 | 1438 | 13.46 | 0.972 (0.945-0.999) | 0.045 | 0.943 (0.916-0.972) | < 0.001 | 0.955 (0.927-0.984) | 0.002 |

| Within URBMI per 10% increase | 1871 | 1012 | 13.24 | 1.029 (0.988-1.071) | 0.173 | 0.984 (0.941-1.029) | 0.483 | 0.988 (0.945-1.034) | 0.608 |

| Within UEBMI per 10% increase | 672 | 426 | 17.43 | 0.893 (0.832-0.958) | 0.002 | 0.902 (0.838-0.971) | 0.006 | 0.916 (0.849-0.988) | 0.023 |

| Within ≤ 60% per 10% increase | 1450 | 924 | 17.50 | 0.958 (0.912-1.006) | 0.084 | 0.97 (0.923-1.02) | 0.239 | 0.986 (0.937-1.037) | 0.579 |

| Within > 60% per 10% increase | 1093 | 514 | 10.13 | 1.294 (1.151-1.456) | < 0.001 | 1.174 (1.029-1.338) | 0.017 | 1.174 (1.026-1.342) | 0.020 |

| Cancer-specify mortality | |||||||||

| Any type per 10% increase | 2543 | 1106 | 8.64 | 0.955 (0.925-0.985) | 0.004 | 0.936 (0.905-0.968) | < 0.001 | 0.947 (0.915-0.980) | 0.002 |

| Within URBMI per 10% increase | 1871 | 776 | 8.63 | 1.001 (0.955-1.048) | 0.982 | 0.982 (0.932-1.034) | 0.486 | 0.984 (0.934-1.036) | 0.533 |

| Within UEBMI per 10% increase | 672 | 330 | 10.74 | 0.877 (0.808-0.951) | 0.002 | 0.890 (0.818-0.969) | 0.007 | 0.899 (0.825-0.981) | 0.016 |

| Within ≤ 60% per 10% increase | 1450 | 741 | 11.74 | 0.976 (0.923-1.031) | 0.381 | 0.992 (0.938-1.049) | 0.776 | 1.010 (0.954-1.068) | 0.742 |

| Within > 60% per 10% increase | 1093 | 365 | 6.01 | 1.380 (1.205-1.581) | < 0.001 | 1.273 (1.095-1.48) | 0.002 | 1.269 (1.087-1.481) | 0.003 |

On the basis of data from 2543 oesophageal cancer patients in the follow-up database of Chongqing University Cancer Hospital in China, we analyzed the relationships of patient mortality with insurance type and out-of-pocket ratio, as well as the joint effects of insurance type and out-of-pocket ratio. Patients in the high out-of-pocket ratio group had a significantly lower cumulative mortality rate than those in the low out-of-pocket ratio group, and patients covered by the URBMI had a significantly lower cumulative mortality rate than those covered by UEBMI. Owing to the higher out-of-pocket ratio of patients covered by URBMI than of patients covered by UEBMI, the trends of the impact of insurance type and out-of-pocket ratio on oesophageal cancer patients were consistent. Moreover, the joint effects of insurance type and out-of-pocket ratio showed that for every 10% increase, the oesophageal cancer-specific mortality risk and all-cause mortality risk for all patients decreased by 5.30% and 4.50%, respectively. This trend was more pronounced in patients covered by UEBMI, with decreases of 10.10% and 8.40%, respectively. However, this trend was not statistically significant in patients covered by URBMI (P > 0.05).

Among patients with the same treatment modality and treatment cost, higher health insurance reimbursement rates (lower out-of-pocket ratios) were associated with greater payment capability for oesophageal cancer patients. This would theoretically facilitate active participation in treatment[15-18] and lead to better prognosis outcomes, such as decreased mortality rates. However, the results of this study contradicted expectations, and three possible reasons were proposed. First, patients covered by URBMI and those with higher out-of-pocket ratios might have utilized high-value consumables and drugs outside the scope of public health insurance coverage for better efficacy. We found that patients in the high out-of-pocket ratio group were more likely to choose surgical treatment, which often involves the use of special medical consumables to improve the operation success rate and postoperative survival quality, as well as drugs with immunoreactivity. These consumables and drugs are often imported, costly, and not fully covered by public health insurance. Second, the study population was in the early stage of the implementation of centralized procurement policies for drugs and consumables, and some of the procured drugs and consumables had side effects and complications, negatively impacting the prognosis of insured patients.

Encouragingly, the Chinese government has recognized these issues. In the 2023 National Medical Insurance Drug Catalog released by the National Medical Security Administration, 111 new drugs were added, including drugs for the treatment of various cancers, such as lung, breast, lymphoma, and oesophageal cancer. This addition is expected to significantly alleviate the economic burden of such drugs[19]. Furthermore, by adhering to the principle of “value-based procurement”, the National Medical Security Administration has established a set of objective and quantitative evaluation indicators focusing on the quality of drugs and consumables. This approach determines pricing on the basis of patient benefits, significantly improving the cost-effectiveness of newly admitted drugs and consumables and increasing the degree of social recognition.

Third, owing to the high cost of self-payment, patients covered by URBMI and those with a high out-of-pocket ratio usually had stronger self-recovery awareness, had better nutritional support, and participated in more rehabilitation exercises after their operations, which consequently resulted in a better surgical prognosis[20,21] and lower mortality risk.

Notably, with every 10% increase in the out-of-pocket ratio, patients covered by UEBMI experienced a decrease in oesophageal cancer-specific mortality risk and overall mortality risk. In contrast, patients in the high out-of-pocket ratio group had an increased risk of oesophageal cancer-specific mortality. This suggests that, on the one hand, the self-payment amount of patients in the high out-of-pocket ratio group may have reached a “Pareto optimum”. Increasing their out-of-pocket spending on medical treatments may simultaneously exacerbate physical and financial burdens, adversely affecting patient prognosis. On the other hand, some patients in the high out-of-pocket ratio group may have relatively severe conditions; therefore, increasing out-of-pocket spending on medical treatments may not fundamentally alter their risk of mortality[22]. Therefore, early oesophageal cancer screening and surveillance for key populations (such as young males)[23-26] and the implementation of early detection, diagnosis, and treatment are essential strategies for radically reducing the risk of oesophageal cancer-specific mortality[23]. We suggest that the medical sector expand the list of basic medical insurance and include more drugs or methods for treating oesophageal cancer patients in medical insurance coverage to reduce patients’ out-of-pocket payments and improve access to medical resources.

The advantages of this study lie in its innovative analysis of the relationship between the mortality rate of oesophageal cancer patients and medical insurance, as well as the relationship between their mortality rate and the combined effects of insurance type and out-of-pocket ratio. The limitations of this study include that we focused on hospital treatment costs for oesophageal cancer patients, excluding out-of-hospital expenses. Additionally, we focused on patients from a specific tertiary cancer hospital in Chongqing without patients from other hospitals. Furthermore, the primary outcome was the mortality rate, and patient survival time was not considered. Future research should consider including all treatment costs for a larger sample of patients and refine the outcomes. In a follow-up study, we will further explore, on the basis of the current results, how much the out-of-pocket ratio can significantly improve patients with prognostic effects; moreover, for those who cannot effectively reduce the risk of death by changing the out-of-pocket ratio, we will explore whether other means or treatments can improve their prognosis. Finally, we intend to conduct a multicentre study to collect data and complete the analysis in multiple regions to increase the credibility of the findings in different regions.

Among the oesophageal cancer patients included in this study, those in the URBMI group and those in the high out-of-pocket ratio group had a lower risk of mortality. This could be because some oesophageal cancer patients prefer to choose high-value and high-quality drugs and consumables that are beyond the scope of public health insurance coverage to achieve better treatment outcomes. Additionally, these patients may have a greater awareness of rehabilitation and invest more in their recovery. To ensure the quality of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis for oesophageal cancer patients, the National Medical Security Administration has recognized these issues. Specifically, the National Medical Security Administration has addressed these issues by expanding public health insurance coverage and strengthening the quality evaluation of drugs and consumables covered by insurance. However, for oesophageal cancer patients who already have a higher out-of-pocket ratio, further increasing the self-payment rate does not reduce their risk of mortality. This means that blindly increasing the use of expensive and high-quality drugs and consumables is not a universal “prescription” for preventing and controlling oesophageal cancer. Effective implementation of measures for early detection, diagnosis, and treatment is the preferred strategy to reduce the risk of oesophageal cancer in high-risk populations.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64037] [Article Influence: 16009.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (174)] |

| 2. | Guo LW, Huang HY, Shi JF, Lv LH, Bai YN, Mao AY, Liao XZ, Liu GX, Ren JS, Sun XJ, Zhu XY, Zhou JY, Gong JY, Zhou Q, Zhu L, Liu YQ, Song BB, Du LB, Xing XJ, Lou PA, Sun XH, Qi X, Wu SL, Cao R, Lan L, Ren Y, Zhang K, He J, Zhang JG, Dai M; Health Economic Evaluation Working Group, Cancer Screening Program in Urban China (CanSPUC). Medical expenditure for esophageal cancer in China: a 10-year multicenter retrospective survey (2002-2011). Chin J Cancer. 2017;36:73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cai Y, Lin J, Wei W, Chen P, Yao K. Burden of esophageal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019. Front Public Health. 2022;10:952087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pan R, Zhu M, Yu C, Lv J, Guo Y, Bian Z, Yang L, Chen Y, Hu Z, Chen Z, Li L, Shen H; China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. Cancer incidence and mortality: A cohort study in China, 2008-2013. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:1315-1323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yang S, Lin S, Li N, Deng Y, Wang M, Xiang D, Xiang G, Wang S, Ye X, Zheng Y, Yao J, Zhai Z, Wu Y, Hu J, Kang H, Dai Z. Burden, trends, and risk factors of esophageal cancer in China from 1990 to 2017: an up-to-date overview and comparison with those in Japan and South Korea. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yao A, Shen X, Chai J, Cheng J, Liu R, Feng R, Wang D. Characteristics and implications of insurance-reimbursed inpatient care for gastric and oesophageal cancers in Anhui, China. Int Health. 2021;13:446-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang Z, Zeng H, Xia R, Liu Q, Sun K, Zheng R, Zhang S, Xia C, Li H, Liu S, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Guo G, Song G, Zhu Y, Wu X, Song B, Liao X, Chen Y, Wei W, Zhuang G, Chen W. Annual cost of illness of stomach and esophageal cancer patients in urban and rural areas in China: A multi-center study. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018;30:439-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Guo LW, Shi CL, Huang HY, Wang L, Yue XP, Liu SZ, Li J, Su K, Dai M, Sun XB, Shi JF. [Economic burden of esophageal cancer in China from 1996 to 2015: a systematic review]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2017;38:102-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Niroomand E, Kumar SR, Goldberg D, Kumar S. Impact of Medicaid Expansion on Incidence and Mortality from Gastric and Esophageal Cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:1178-1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huang H, Fang W, Lin Y, Zheng Z, Wang Z, Chen X, Yu K, Lu G. Predictive Model for Overall Survival and Cancer-Specific Survival in Patients with Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. J Oncol. 2021;2021:4138575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dou G, Wang Q, Ying X. Reducing the medical economic burden of health insurance in China: Achievements and challenges. Biosci Trends. 2018;12:215-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen C, Liu M. Achievements and Challenges of the Healthcare System in China. Cureus. 2023;15:e39030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tramontano AC, Chen Y, Watson TR, Eckel A, Hur C, Kong CY. Esophageal cancer treatment costs by phase of care and treatment modality, 2000-2013. Cancer Med. 2019;8:5158-5172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang Y, Lei H, Li X, Zhou W, Wang G, Sun A, Wang Y, Wu Y, Peng B. Lung Cancer-Specific Mortality Risk and Public Health Insurance: A Prospective Cohort Study in Chongqing, Southwest China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:842844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Parsons M, Lloyd S, Johnson S, Scaife C, Varghese T, Glasgow R, Garrido-Laguna I, Tao R. Refusal of Local Therapy in Esophageal Cancer and Impact on Overall Survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:663-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Schlottmann F, Gaber C, Strassle PD, Herbella FAM, Molena D, Patti MG. Disparities in esophageal cancer: less treatment, less surgical resection, and poorer survival in disadvantaged patients. Dis Esophagus. 2020;33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Asokan S, Sridhar P, Qureshi MM, Bhatt M, Truong MT, Suzuki K, Mak KS, Litle VR. Presentation, Treatment, and Outcomes of Vulnerable Populations With Esophageal Cancer Treated at a Safety-Net Hospital. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;32:347-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rahouma M, Harrison S, Kamel M, Nasar A, Lee B, Port J, Altorki N, Stiles B. Consequences of Refusing Surgery for Esophageal Cancer: A National Cancer Database Analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:1476-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yang Y, Zhang Y, Wagner AK, Li H, Shi L, Guan X. The impact of government reimbursement negotiation on targeted anticancer medicines use and cost in China: A cohort study based on national health insurance data. J Glob Health. 2023;13:04083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mayer PK, Kao PY, Lee YC, Liao YF, Ho WC, Ben-Arie E. Acupuncture effect on dumping syndrome in esophagus cancer patients with feeding jejunostomy: A study protocol for a single blind randomized control trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e33895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Su J, Jiang Y, Fan X, Tao R, Wu M, Lu Y, Hua Y, Jin J, Guo Y, Lv J, Pei P, Chen Z, Li L, Zhou J. Association between physical activity and cancer risk among Chinese adults: a 10-year prospective study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2022;19:150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ye ZM, Xu Z, Wang HL, Wang YY, Chen ZC, Zhou Q, Li XP, Zhang YY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy as the first-line treatment for advanced esophageal cancer. Cancer Med. 2023;12:6182-6189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zeng H, Ran X, An L, Zheng R, Zhang S, Ji JS, Zhang Y, Chen W, Wei W, He J; HBCR Working Group. Disparities in stage at diagnosis for five common cancers in China: a multicentre, hospital-based, observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e877-e887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tian H, Hu Y, Li Q, Lei L, Liu Z, Liu M, Guo C, Liu F, Liu Y, Pan Y, Dos-Santos-Silva I, He Z, Ke Y. Estimating cancer survival and prevalence with the Medical-Insurance-System-based Cancer Surveillance System (MIS-CASS): An empirical study in China. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;33:100756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Seo JH, Kim YD, Park CS, Han KD, Joo YH. Hypertension is associated with oral, laryngeal, and esophageal cancer: a nationwide population-based study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:10291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhang S, Guo J, Zhang H, Li H, Hassan MOO, Zhang L. Metastasis pattern and prognosis in men with esophageal cancer patients: A SEER-based study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e26496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |