Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.103311

Revised: January 1, 2025

Accepted: February 10, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 130 Days and 2.9 Hours

Palliative care for unresectable pancreatic cancer (PC) focuses mainly on the symptoms of the disease, including abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, and malnutrition. Biliary stent placement using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to relieve biliary obstruction has become an internationally recognized treatment. Although a few studies have evaluated the efficacy of endoscopic pancreatic duct stenting in advanced PC, no consensus exists on the use of endoscopic treatment to relieve pain and improve nutritional status.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of early pancreatic duct stenting in patients with unresectable PC.

Patients with unresectable PC were recruited. The participants were randomized into two groups: The double-stent group underwent ERCP with a fully-covered self-expandable metallic biliary stent (FCSEMS) and a pancreatic duct stent, while the single-stent group underwent ERCP with an FCSEMS only. Abdominal pain, nutritional status, and incidence of adverse events were compared between the two groups using the SPSS software.

Seventy-eight patients with unresectable PC were included in the analysis (40 and 38 in the double- and single-stent groups, respectively). The median pain scores of patients in the double-stent group were lower than those in the single-stent group at 1 (0 vs 2.5, P = 0.002), 2 (0 vs 3, P < 0.001), 3 (0 vs 4, P < 0.001), and 6 months (0 vs 4, P < 0.001) after ERCP. Total serum protein levels in patients in the double-stent group were higher than those in the single-stent group (66.6 ± 8.4 g/L vs 60.4 ± 4.0 g/L, P = 0.046) 6 months postoperatively. The body mass index (BMI) of patients in both groups decreased at six months. However, the BMI in the single-stent group was higher than that in the double-stent group (P < 0.001).

Early pancreatic duct stenting reduces abdominal pain and improves nutritional status in patients with unre

Core Tip: The early and effective improvement of abdominal pain and malnutrition in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer (PC) is a key component of clinical treatment. Our findings suggest that early pancreatic duct stenting can reduce abdominal pain and improve the nutritional status of patients with unresectable PC.

- Citation: Sun MH, Shen HZ, Jin HB, Yang JF, Zhang XF. Efficacy and safety of early pancreatic duct stenting for unresectable pancreatic cancer: A randomized controlled trial. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(4): 103311

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i4/103311.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.103311

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is a highly lethal malignancy and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, accounting for 510000 new cases and 467000 deaths annually, according to GLOBOCAN 2022 estimates[1]. Owing to the insidious onset of PC, 80%-85% of patients present with unresectable disease at the time of detection, and the 5-year survival rate is only 11%[1,2]. Therefore, for patients with unresectable disease, clinical treatment is mainly aimed at addressing complications, including obstructive jaundice, abdominal pain, digestive outlet obstruction, and malnutrition, to improve the quality of life.

Pain is present in 80% of the patients throughout the course of the disease, with nearly half experiencing severe pain that seriously affects their diet, sleep, and mood[3]. Two main mechanisms underlie cancer pain: Pancreatic neuropathy and pancreatic duct obstruction[3,4]. The mechanism of ductal obstructive pain is believed to be similar to that of chronic pancreatitis, in that compression of the pancreatic duct by the tumor affects the secretion of pancreatic enzymes, leading to increased interstitial and intraductal pressures, which in turn produces pain[3]. Computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging of the pancreas often reveals dilatation of the pancreatic duct due to tumor compression. Abdominal pain caused by pancreatic duct obstruction can be relieved by placing a pancreatic duct stent (PDS) to relieve pancreatic duct hypertension[5].

Almost 85% of patients are at high risk of malnutrition or are already malnourished, with significant weight loss and functional disabilities[6]. Malnutrition is caused by tumor hypermetabolism, loss of appetite, and malabsorption of food due to poor flow of bile and pancreatic juice. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) caused by tumor compression of the pancreatic duct has been observed in 72% of patients[7]. In clinical practice, gastrointestinal symptoms are primarily improved by oral supplementation of digestive enzyme preparations.

Most patients seek treatment for obstructive jaundice. While endoscopic biliary stenting relieves biliary obstruction, patients without concomitant moderate to severe pancreatic duct dilatation and severe obstructive pain do not typically undergo early intervention for pancreatic duct stenting. However, > 70% of patients experience symptoms of pancreatic duct obstruction, such as abdominal pain and dyspepsia, in later stages. Subsequent endoscopic placement of a PDS not only increases hospitalization costs and the incidence of adverse events (AEs), but also reduces the patient’s quality of life. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the improvements in abdominal pain and nutritional status in patients with unresectable PC who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for biliary stenting to relieve biliary obstruction, along with early placement of a PDS, prior to the development of moderate-to-severe pancreatic ductal dilatation and abdominal pain.

Consecutive patients diagnosed with PC (diagnostic criteria: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline 2023[8]) at the Department of Gastroenterology, Affiliated Hangzhou First People’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Westlake University (Zhejiang, China) were enrolled between January 2021 and December 2022. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1.

| The inclusion and exclusion criteria | |

| Inclusion criteria | (1) Diagnosed with pancreatic cancer |

| (2) Confirmed unresectable pancreatic cancer (according to 8th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual) | |

| (3) Age ≥ 18 years old | |

| (4) Presence of biliary obstruction: Imaging showed that the bile duct diameter was greater than 1.0 cm with elevated direct bilirubin (greater than 50 mmol/L) | |

| (5) The diameter of the main pancreatic duct is less than 5 mm | |

| (6) Pain score ≤ 4 point | |

| Exclusion criteria | (1) Unable to give informed consent |

| (2) Life expectancy of less than 4 weeks | |

| (3) Pregnancy | |

| (4) Severe comorbidities precluding the endoscopic procedure (such as cardiopulmonary disease, sepsis, or a bleeding disorder) |

This study was designed as an open-label, randomized controlled trial. The patients were randomly assigned to two groups at a 1:1 ratio: Double-stent; and single-stent. The double-stent group underwent ERCP followed by the placement of a fully covered self-expandable metallic biliary stent (FCSEMS) and PDS, whereas the single-stent group underwent ERCP followed by FCSEMS placement without PDS. A scientific assistant created the order using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). This assistant was not involved in the subsequent enrollment of patients, data collection, or data analysis. The investigators performing the follow-up were blinded to the clinical data and treatment groups until the end of the study.

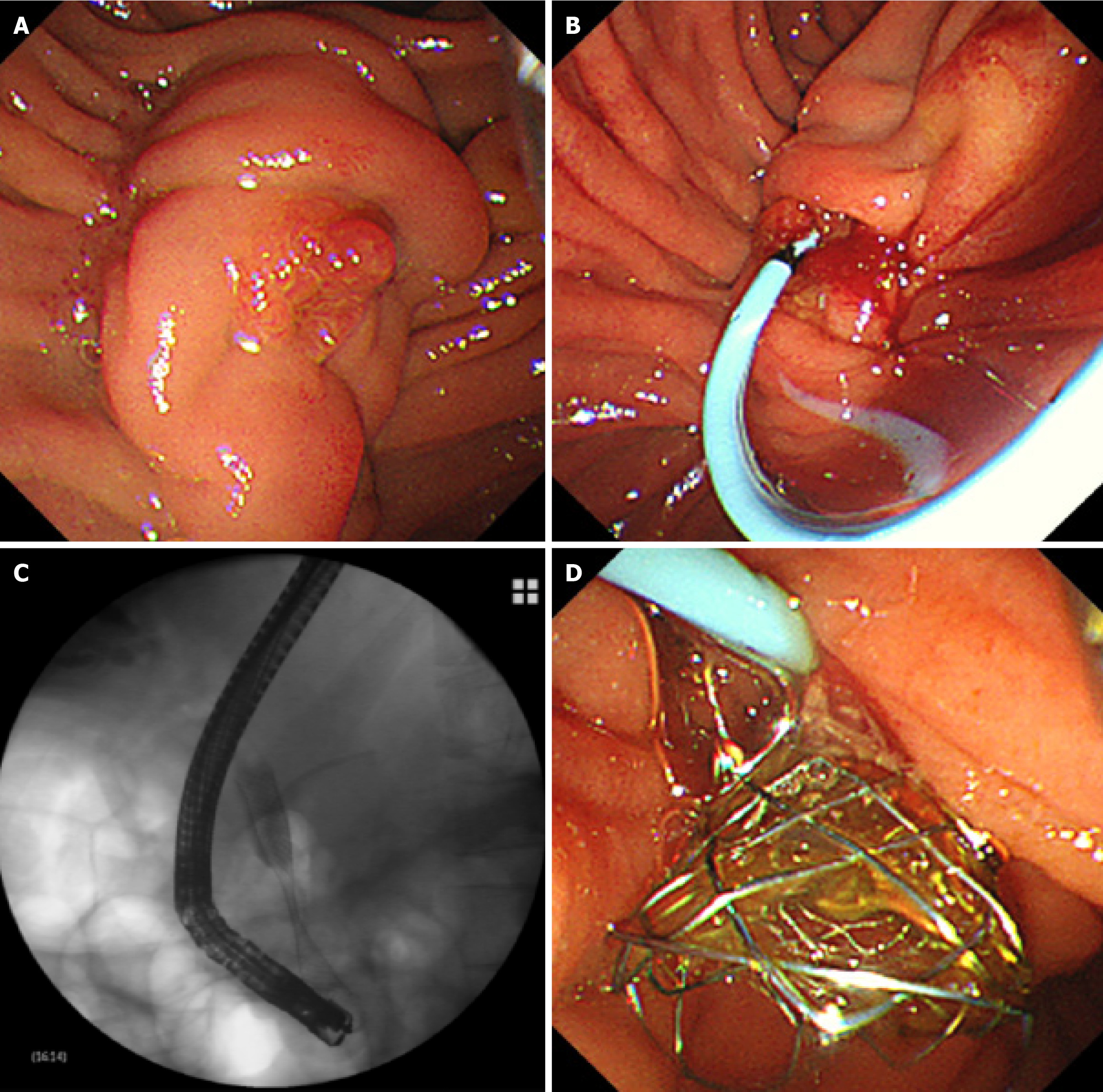

The patients were positioned prone or laterally and received oxygen during electrocardiographic monitoring. After the endoscope reached the duodenal papilla, the papillary morphology and the manifestations of tumor invasion were observed. An ERCP catheter and guidewire (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, United States) were used for pancreatic duct intubation. After successful intubation, pancreatography was performed to identify the main stricture location and a suitable PDS (Xinchang, Shanghai, China) was placed. Common bile duct cannulation and cholangiography were performed to identify the primary stricture location. Accordingly, a suitable FCSEMS was selected for placement in the biliary duct. A small incision (0.3 cm) was made along the bile duct by using a triple-lumen sphincterotome (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). After papillary dilation, an FCSEMS was inserted into the biliary duct along the guidewire, with both ends 2 cm across the obstruction (Figure 1).

Post-ERCP AEs, including bleeding, acute pancreatitis, perforation, biliary infection, and adverse outcomes requiring hospital admission, were monitored. The severity of AEs was graded according to the Cotton criteria[9]. The frequency and severity of postoperative AEs and the recovery time in the two groups were recorded.

All patients were asked to rate their pain levels using a visual analog scale (VAS) preoperatively and 1, 4, 8, 12, and 24 weeks after ERCP. Routine blood and liver function tests were performed preoperatively, and at 1 and 4 weeks postoperatively. Serum protein levels and body mass index (BMI) were monitored preoperatively 3 and 6 months after ERCP. Abdominal computed tomography was performed every 3 months to evaluate the position of the stent. Abdominal pain was the primary outcome measure in this study. The secondary outcome measures included liver function, nutritional status, technical success rate, and post-ERCP AEs. The technical success rate was defined as the successful placement of the target stent under the endoscopy.

According to previous studies, the mean (± SD) pain score of patients in the single-stent group was 7.8 ± 1.3 at 6 months after ERCP, and that the pain score in the double-stent group was expected to decrease by 1.0 point. Setting the bilateral

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, United States). Measurement data with a normal distribution are expressed as mean ± SD, while those with a skewed distribution are expressed as median [interquartile range (IQR)]. Comparisons between the two groups were performed using Student’s t-test or nonparametric tests. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the two groups. Paired-sample t-tests were used for intragroup comparisons.

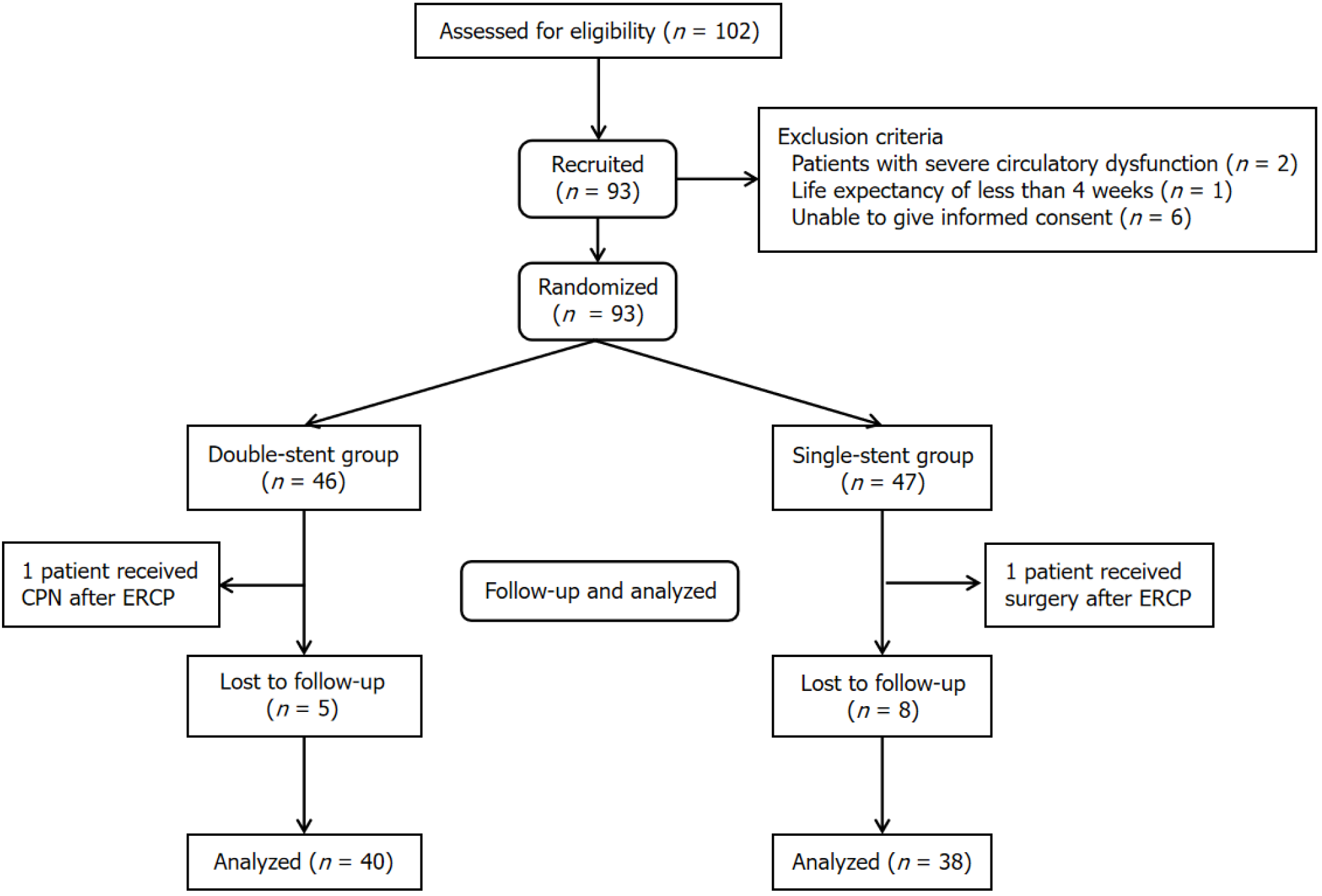

Between January 2021 and December 2022, 102 patients were screened, and nine were excluded. One patient from the double-stent group was excluded because of celiac plexus neurolysis after ERCP. One patient in the single-stent group was excluded because of surgery after ERCP. Thirteen patients (5 in the double-stent group and 8 in the single-stent group) were lost to follow-up; thus, 40 and 38 patients in the double-stent and single-stent groups, respectively, were included in the final analysis (Figure 2). There were no statistical differences in the background demographics between the groups, except for the method PC diagnostic method (Table 2).

| Double-stent group (n = 40) | Single-stent group (n = 38) | P value | |

| Sex, male/female, n | 20/20 | 16/22 | 0.4841 |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 73 ± 11 | 71 ± 12 | 0.3332 |

| Hypertension | 12 (30.0) | 17 (44.7) | 0.1781 |

| Diabetes | 14 (35.0) | 12 (31.6) | 0.7491 |

| Diagnostic method | 0.0141 | ||

| Biopsy | 21 (52.5) | 30 (78.9) | - |

| Imaging | 19 (47.5) | 8 (21.1) | - |

| Tumor location | 0.3421 | ||

| Head | 37 (92.5) | 35 (92.1) | - |

| Neck | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.3) | - |

| Body | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Tail | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | - |

| Tumor staging | 0.6871 | ||

| III stage | 27 (67.5) | 24 (63.2) | - |

| IV stage | 13 (32.5) | 14 (36.8) | - |

| Chemotherapy | 16 (40.0) | 11 (28.9) | 0.3341 |

| Analgesic | > 0.999 | ||

| None | 23 (57.5) | 23 (60.5) | - |

| Nonopioid analgesic | 16 (40.0) | 15 (39.5) | - |

| Moderate opioid | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Strong opioids | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

There were no significant differences in the VAS scores between the two groups preoperatively or at 1 week postoperatively. The median VAS scores of the patients in the double-stent group were lower than those in the single-stent group at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after ERCP (P < 0.05; Table 3). We categorized the patients' abdominal pain into pain-free/mild pain and moderate/severe pain based on VAS scores. The incidence of pain-free or mild pain at 2 months after ERCP was 95.0% and 68.4% in the single- and double-stent groups, respectively, and the incidence of pain-free or mild pain at 3 months after ERCP was 95.0% and 47.4%, respectively. The incidence of pain-free or mild pain at 6 months after ERCP was 77.5% and 15.8%, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001; Table 4). In addition, we compared postoperative analgesic drug use according to the World Health Organization (WHO) three-step analgesic ladder. The double-stent group exhibited significantly lower use of moderate and strong opioids than the single-stent group at 1, 3, and 6 months after ERCP (Table 5).

| Point, M (IQR) | Double-stent group (n = 40) | Single-stent group (n = 38) | P value |

| Preoperative | 0 (2) | 0 (2) | 0.655 |

| After 1 week | 0 (1) | 0 (2) | 0.065 |

| After 1 month | 0 (2) | 2.5 (4) | 0.002 |

| After 2 months | 0 (1) | 3 (4) | < 0.001 |

| After 3 months | 0 (1) | 4 (2) | < 0.001 |

| After 6 months | 1.5 (3) | 4 (1) | < 0.001 |

| Pain-free/mild pain | Moderate/severe pain | Difference, % (95%CI) | P value | |||

| Double-stent group | Single-stent group | Double-stent group | Single-stent group | |||

| Preoperative | 39 (97.5) | 36 (94.7) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.3) | 0.056 (0.175, 0.063) | 0.610 |

| After 1 week | 38 (95) | 35 (92.1) | 2 (5) | 3 (7.9) | 0.058 (0.207, 0.091) | 0.671 |

| After 1 month | 37 (92.5) | 31 (81.6) | 3 (7.5) | 7 (18.4) | 0.218 (-0.407, -0.029) | 0.187 |

| After 2 months | 38 (95) | 26 (68.4) | 2 (5) | 12 (31.6) | 0.532 (-0.711, -0.353) | 0.003 |

| After 3 months | 38 (95.0) | 18 (47.4) | 2 (5.0) | 20 (52.6) | 0.85 (0.7304, 0.9656) | < 0.001 |

| After 6 months | 31 (77.5) | 6 (15.8) | 9 (22.5) | 32 (84.2) | 0.13 (1.0185, 1.4495) | < 0.001 |

| None | Nonopioid analgesic | Moderate opioid | Strong opioid | P value | ||

| After 1 month | Double-stent group | 24 (60.0) | 13 (32.5) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.0) | 0.026 |

| Single-stent group | 11 (28.9) | 19 (42.1) | 5 (13.2) | 3 (7.9) | ||

| After 2 months | Double-stent group | 22 (55.0) | 14 (35.0) | 2 (5.0) | 2 (5.0) | 0.051 |

| Single-stent group | 10 (26.3) | 18 (47.4) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (15.8) | ||

| After 3 months | Double-stent group | 19 (57.5) | 18 (57.5) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.0) | < 0.001 |

| Single-stent group | 6 (15.8) | 14 (36.8) | 8 (21.1 | 10 (36.3) | ||

| After 6 months | Double-stent group | 16 (40.0) | 16 (40.0) | 5 (12.5) | 3 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| Single-stent group | 3 (7.9) | 3 (7.9) | 16 (42.1) | 16 (42.1) | ||

The changes in albumin, serum total protein levels, and BMI showed no significant differences 3 months postoperatively. Serum total protein level in patients in the double-stent group was higher than that in the single-stent group at 6 months postoperatively (66.6 ± 8.4 g/L vs 60.4 ± 4.0 g/L, P = 0.046). The BMI of patients in both groups decreased at 6 months; however, the decrease in BMI in the single-stent group was statistically significant (P < 0.001; Table 6).

| Double-stent group (n = 40) | Single-stent group (n = 38) | P value | |

| Albumin, mean ± SD, g/L | |||

| Preoperative | 33.5 ± 5.4 | 33.7 ± 4.9 | 0.866 |

| After 3 months | 35.1 ± 4.2 | 35.0 ± 4.7 | 0.962 |

| After 6 months | 35.2 ± 4.6 | 32.2 ± 4.1 | 0.179 |

| Serum total protein, mean ± SD, g/L | |||

| Preoperative | 63.5 ± 6.8 | 62.2 ± 7.4 | 0.431 |

| After 3 months | 63.4 ± 7.1 | 62.6 ± 5.9 | 0.775 |

| After 6 months | 66.6 ± 8.4 | 60.4 ± 4.0 | 0.046 |

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | |||

| Preoperative | 21.3 ± 3.1 | 20.8 ± 3.1 | 0.448 |

| After 3 months | 19.7 ± 2.9 | 19.4 ± 3.2 | 0.756 |

| After 6 months | 20.3 ± 3.1 | 17.9 ± 2.7c | 0.061 |

All the patients underwent SEMS placement with stent sizes of 10 mm × 4 cm (2/78), 10 mm × 6 cm (75/78), and 10 mm × 8 cm (1/78). The PDS sizes in the double-stent group were 5 Fr (26/40), 6 Fr (6/40), and 7 Fr (8/40), respectively.

There was no significant difference in the technical success rate (97.5% vs 100%, P = 0.327) or post-ERCP AEs [4/40 (10.0%) vs 6/38 (15.8%), P = 0.710] between the groups. In the double-stent group, one patient failed placement of SEMS on the first attempt; only a nasobiliary tube was placed for biliary drainage, and a second attempt was made 3 days later to successfully place an FCSEMS and PDS. Four AEs occurred in the double-stent group: Mild acute pancreatitis (n = 3) and acute cholangitis (n = 1). Six AEs occurred in the single-stent group: Mild acute pancreatitis (n = 5) and acute cholangitis (n = 1). All patients improved with conservative treatment(s) (Table 7).

| Double-stent group (n = 40) | Single-stent group (n = 38) | P value | |

| Adverse events | 4 (10.0) | 6 (15.8) | 0.710 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 3 (7.5) | 5 (13.2) | - |

| Acute cholangitis | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.6) | - |

| Hemorrhage | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Perforation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

The results of the present study demonstrate that early PDS can reduce abdominal pain and improve the nutritional status of patients with unresectable PC. There were no significant differences in the ERCP success rates or post-ERCP AEs between the groups.

For the endoscopic treatment of abdominal pain, our predecessors performed preliminary explorations and found that PDS may have a palliative effect on obstructive pain in patients with PC. Drawing on the endoscopic approach to chronic pancreatitis, in 1898, Harrison and Hamilton[10] first reported a case of relief of intractable abdominal pain in a patient with PC by placing a PDS to relieve pancreatic ductal obstruction, and the patient experienced recurrence with severe abdominal pain after the stent was dislodged. Over the following 15 years, Costamagna et al[11], Tham et al[12], and Wehrmann et al[13], conducted small-sample observational studies, that confirmed the efficacy of PDS in patients with obstructive pain, with postoperative pain relief rates ranging from 61% to 100%. However, these are case reports and small-sample observational studies that need to be further confirmed by high-quality controlled studies. In a prospective study by Gao et al[14] in 2014, patients with advanced PC were divided into pancreatic duct dilation and non-dilatation groups to explore the efficacy of PDS in improving pain. The results demonstrated higher pain improvement rates in the pancreatic duct dilation group than in the non-dilation group at 1 month (74.3% vs 16.1%, P < 0.001) and 3 months (55.2% vs 16.7%, P < 0.001). Based on these findings, the PDS appeared to be more effective in patients with obstructive pain and pancreatic duct dilatation.

Our team conducted a prospective controlled study in 2013 and found that the simultaneous placement of a biliary stent and a PDS in patients with PC presenting with obstructive jaundice provided superior pain relief and improvement in quality of life to the placement of a biliary stent alone[15]. However, patients in previous studies had moderate-to-severe pain or even endured pain for a significant period and required long-term pain relief with opioid analgesics. Currently, interventional analgesic therapy is recommended as soon as possible without waiting for the poor effects of strong opioid analgesics or intolerance to the adverse effects of opioid analgesics[16]. Therefore, we envisioned that if a biliary stent is placed to relieve biliary obstruction when the patient is not experiencing pain or only mild pain, PDS should be placed at this early stage, thus leaving the patient in a state of pain-free or mild pain state for a prolonged period after the procedure. The mean preoperative VAS score of the 78 patients in our study was 0.8, and the median VAS scores were significantly lower in the double-stent group than in the single-stent group at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months postoperatively (P < 0.05). Postoperative pain scores increased in both groups 6 months after ERCP. This is because the included patients were at the stage of tumor progression, and the placement of the biliopancreatic stent was only a palliative treatment; as the disease progresses, neuropathy and organ failure caused by the direct action of the tumor cause increased pain in the patients. Patients in the double-stent group had a higher incidence of no or mild pain than those in the single-stent group at 2 (95.0% vs 68.4%, P = 0.003), 3 (95.0% vs 47.4%, P < 0.001), and 6 months (77.5% vs 15.8%, P < 0.001). In addition, we compared postoperative analgesic drug use according to the WHO three-step analgesic ladder. The use of moderate and strong opioids was lower in the double-stent group than in the single-stent group at 1, 3, and 6 months post-ERCP.

Another advantage of PDS demonstrated in this study is that it can improve nutritional status. There are two possible explanations for this observation. First, patients are either pain-free or experience only mild pain for a prolonged period after PDS, which improves their mood, appetite, and sleep. Second, after PDS, pancreatic juice can pass into the intestine, facilitating the digestion and absorption of food. PEI occurs in more than 70% of patients with advanced PC, and tumors in the pancreatic head have a higher prevalence than those in the tail or body[7]. It is caused by a decrease in digestive enzymes secreted by the pancreas, and the tumor compresses the main pancreatic duct. Thus, pancreatic juices are unable to enter the intestinal tract, and digestive and absorptive functions are impaired. In clinical practice, PEI is treated with oral supplementation of adequate amounts of digestive enzyme preparations that effectively improve abdominal symptoms and promote weight gain[7]. No relevant clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of PDS in improving the nutritional status or PEI in patients with advanced PC. In our study, BMI, serum total protein, and albumin levels were used to evaluate the nutritional status of patients with advanced PC. Six months after ERCP, the double-stent group had a higher total protein level than the single-stent group (66.6 ± 8.4 g/L vs 60.4 ± 4.0 g/L, P = 0.046), and the single-stent group experienced more weight loss than the double-stent group (P < 0.001).

According to the literature, the incidence of AEs after ERCP ranges from 1.3% to 14.7%, and includes bleeding, acute pancreatitis, perforation, and biliary infection. The incidence of acute pancreatitis reported in meta-analyses varies from 3.5% to 9.7%[17]. Procedure-related risk factors for acute pancreatitis in our study included difficult cannulation, pancreatic injection, pancreatic endoscopic sphincterotomy, and biliary balloon sphincter dilation. The double-stent group required manipulation within the pancreatic duct during ERCP, and the placement of the PDS itself could play a role in preventing acute pancreatitis. Our study demonstrated that, although the number of cases of acute pancreatitis in the double-stent group was smaller than that in the single-stent group, the difference in the incidence of acute pancreatitis between the two groups was not statistically significant (7.5% vs 13.2%, P > 0.05).

The present study has some limitations. This was an open-label, single-center, small-sample study. Owing to the nature of this study, it was not possible to blind the subjects and investigators, and there may have been unconscious information bias, which may have affected the accuracy of the study results. Owing to the small sample size, the study was not stratified by the age of the patients, the site of the tumor, or tumor stage, and there may be confounding bias, which may affect the accuracy of the study results. The results of this study need to be validated in additional medical centers with larger sample sizes. In addition, the present study had a short follow-up period of 6 months, and it may be better to extend the follow-up period to 9- or even 12- months to accumulate more adequate data. In addition, this study did not sufficiently explore PEI. Fecal elastase-1 Levels should be further examined in both groups to better evaluate the effects of PDS on PEI treatment[7].

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that early PDS can reduce abdominal pain and improve the nutritional status of patients with unresectable PC. Technical success rates and AEs were similar between groups.

We gratefully acknowledge the support from our research assistants, for their contributions to study design, patient enrollment, and follow-up.

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 8001] [Article Influence: 8001.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Mizrahi JD, Surana R, Valle JW, Shroff RT. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2020;395:2008-2020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 869] [Cited by in RCA: 1660] [Article Influence: 332.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Koulouris AI, Banim P, Hart AR. Pain in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer: Prevalence, Mechanisms, Management and Future Developments. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:861-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | di Mola FF, di Sebastiano P. Pain and pain generation in pancreatic cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:919-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Siddappa PK, Hawa F, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Abu Dayyeh BK, Chandrasekhara V, Topazian MD, Bazerbachi F. Endoscopic pancreatic duct stenting for pain palliation in selected pancreatic cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2021;9:105-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Poulia KA, Antoniadou D, Sarantis P, Karamouzis MV. Pancreatic Cancer Prognosis, Malnutrition Risk, and Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2022;14:442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Iglesia D, Avci B, Kiriukova M, Panic N, Bozhychko M, Sandru V, de-Madaria E, Capurso G. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:1115-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Conroy T, Pfeiffer P, Vilgrain V, Lamarca A, Seufferlein T, O'Reilly EM, Hackert T, Golan T, Prager G, Haustermans K, Vogel A, Ducreux M; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Pancreatic cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:987-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 97.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cotton PB, Garrow DA, Gallagher J, Romagnuolo J. Risk factors for complications after ERCP: a multivariate analysis of 11,497 procedures over 12 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:80-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Harrison MA, Hamilton JW. Palliation of pancreatic cancer pain by endoscopic stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:443-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Costamagna G, Gabbrielli A, Mutignani M, Perri V, Crucitti F. Treatment of "obstructive" pain by endoscopic drainage in patients with pancreatic head carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:774-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tham TC, Lichtenstein DR, Vandervoort J, Wong RC, Slivka A, Banks PA, Yim HB, Carr-Locke DL. Pancreatic duct stents for "obstructive type" pain in pancreatic malignancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:956-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wehrmann T, Riphaus A, Frenz MB, Martchenko K, Stergiou N. Endoscopic pancreatic duct stenting for relief of pancreatic cancer pain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:1395-1400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gao F, Ma S, Zhang N, Zhang Y, Ai M, Wang B. Clinical efficacy of endoscopic pancreatic drainage for pain relief with malignant pancreatic duct obstruction. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:6823-6827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fan Z, Zhang XF, Zhang X, Lv W, Guo YH, Yuan QF, Zhao YA. [Biliary-pancreatic double stents for pancreatic cancer with obstructive jaundice]. Zhonghua Xiaohua Neijing Zazhi. 2013;30:181-184. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Fallon M, Dierberger K, Leng M, Hall PS, Allende S, Sabar R, Verastegui E, Gordon D, Grant L, Lee R, McWillams K, Murray GD, Norris L, Reid C, Sande TA, Caraceni A, Kaasa S, Laird BJA. An international, open-label, randomised trial comparing a two-step approach versus the standard three-step approach of the WHO analgesic ladder in patients with cancer. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:1296-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dumonceau JM, Kapral C, Aabakken L, Papanikolaou IS, Tringali A, Vanbiervliet G, Beyna T, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Hritz I, Mariani A, Paspatis G, Radaelli F, Lakhtakia S, Veitch AM, van Hooft JE. ERCP-related adverse events: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2020;52:127-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 99.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |