Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.103131

Revised: January 2, 2025

Accepted: February 18, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 136 Days and 9.1 Hours

Studies on the application of recombinant human endostatin (RH-endostatin) intraperitoneal perfusion in gastric cancer (GC) with malignant ascites are limited.

To explore the effectiveness, prognosis, and safety of intraperitoneal RH-endostatin perfusion in treating patients with GC and malignant ascites.

Patients with GC and malignant ascites were divided into the cisplatin intraperitoneal perfusion (control group) group and the cisplatin combined with RH-endostatin intraperitoneal perfusion group (RH-endostatin group). Efficient ascites control, overall survival (OS), quality of life, and adverse events were observed, and possible influencing factors on prognosis outcomes analyzed.

We identified no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the control and RH-endostatin groups. The latter group had higher ascites control rates than the control group. Treatment methods were identified as an independent OS factor. Clinically, RH-endostatin-treated patients had significantly improved OS rates when compared with control patients, particularly in those with small and moderate ascites volumes. Quality of life improvements in control patients were significantly lower when compared with RH-endostatin patients. Adverse events were balanced between the groups.

Overall, intraperitoneal RH-endostatin improved treatment efficacy and prolonged prognosis in patients with GC and malignant ascites. This approach may benefit further clinical applications for treating GC.

Core Tip: Recombinant human endostatin (RH-endostatin) is an angiogenesis-inhibiting drug; the present study demonstrates that the intraperitoneal perfusion of RH-endostatin prolongs the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer (GC) and malignant ascites, particularly in patients with small and moderate ascites volumes. Intraperitoneal RH-endostatin perfusion significantly improves the quality of life in patients with GC and ascites, with less toxicity.

- Citation: Liu Y, Liu HG, Zhao C. Intraperitoneal perfusion of endostatin improves the effectiveness and prolongs the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(4): 103131

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i4/103131.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.103131

Malignant ascites is a phenomenon observed in end-stage events and a common complication in numerous cancers; patients with malignant ascites have a decreased quality of life and a poor prognosis[1]. Peritoneal metastasis (PM) is a common occurrence in gastric cancer (GC). Notably, more than 50% of GC cases with PM are accompanied by malignant ascites[2]. Therapeutically, combined systemic chemotherapy and intraperitoneal drug infusion treatments are commonly used for patients with GC and malignant ascites[3]. Intraperitoneal perfusion therapy can increase tumor cell exposure times to drugs in the abdominal cavity, thus enhancing local drug concentrations. It was previously reported that peritoneal drug infusion combined with systemic chemotherapy improved the quality of life and prolonged survival in patients with GC and PM[4]. However, based on the peritoneal carcinomatosis index, cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy has led to promising results only in patients with early-stage GC or in selected patients with PM[5]. Abdominal puncture, ascites drainage, and intraperitoneal drug infusion with B-ultrasound/computed tomography (CT) are commonly used techniques for the majority of patients with GC with a higher peritoneal carcinomatosis index.

Controversy exists regarding intraperitoneal perfusion drugs. Although multiple clinical trials have reported on the clinical efficacy of infusing new drugs[6], these cannot be widely used in clinical practice. Intraperitoneal chemotherapeutic drug perfusion remains the mainstay for inhibiting peritoneal tumors and controlling ascites. Therefore, the identification of more efficient intraperitoneal perfusion drugs with low toxicity is urgently needed. Recombinant human endostatin (RH-endostatin) is an angiogenesis-inhibiting drug; it effectively suppresses endothelial cell migration, prevents tumor angiogenesis, and lowers the nutritional supply to tumor cells, ultimately inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis[7]. Clinically, RH-endostatin has yielded encouraging results across different solid tumor types[8]. Researchers have explored RH-endostatin serosal cavity infusion in pleural metastasis and PM in advanced-stage tumors. Some researchers reported that intrapleural RH-endostatin infusion alone or RH-endostatin combined with chemotherapeutic drugs exerted significant effects on lung adenocarcinoma with malignant pleural effusion[9]. Several prospective studies also demonstrated that RH-endostatin peritoneal perfusion enhanced treatment efficacy and improved the quality of life of patients with malignant cancers, with fewer side effects[10]. In a previous study using a mouse GC model with PM, simultaneous and sequential RH-endostatin and cisplatin inhibited peritoneal vascular endothelial growth[11].

However, studies investigating intraperitoneal RH-endostatin perfusion in GC with malignant ascites are currently limited. Therefore, to address this gap, we evaluated the clinical efficacy, prognoses, and safety of intraperitoneal RH-endostatin perfusion in patients with GC and malignant ascites.

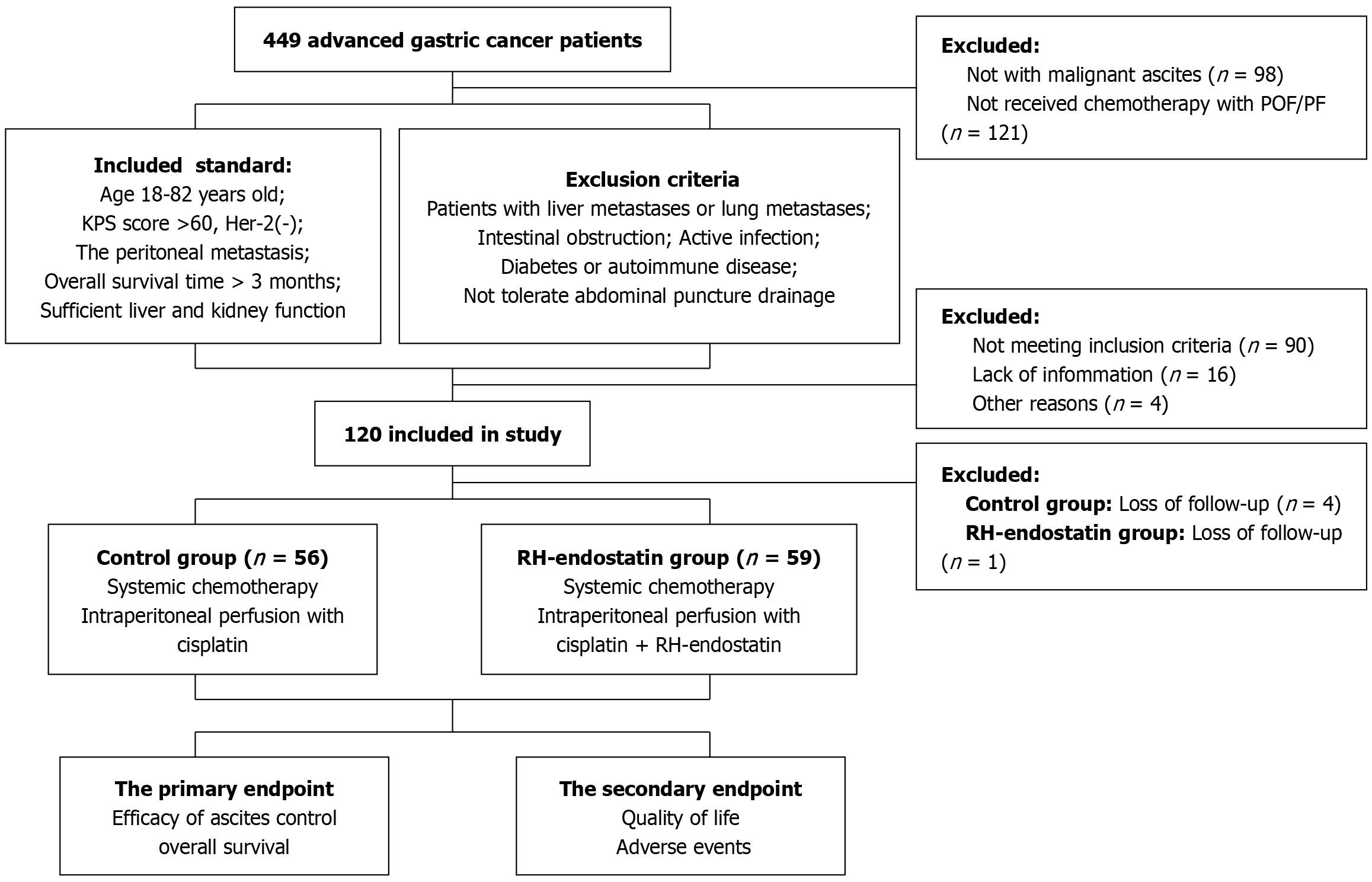

Between April 2021 and January 2022, patients with GC and malignant ascites at the First Teaching Hospital of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine were enrolled in this study. Eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) Aged 18-82 years; (2) A Karnofsky performance scale (KPS) score > 60; (3) An estimated overall survival (OS) time of > 3 months; (4) An Her-2 (-) status; (5) PM diagnosed by an abdominal or pelvic CT scan, and abdominal ascites measured using B-ultrasound; and (6) Sufficient liver and kidney function to tolerate systemic therapy.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with GC and liver or lung metastases; (2) Severe gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal obstruction, or active infection; (3) Severe or uncontrollable diabetes or autoimmune disease; (4) Patients with GC who could not tolerate abdominal puncture drainage; and (5) Patients who underwent previous palliative gastrectomy (Figure 1).

All 115 patients underwent systemic chemotherapy and intraperitoneal perfusion therapy. Systemic chemotherapy regimens were based on NCCN guidelines [oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin regimen or paclitaxel/5-FU/leucovorin regimen]. Intraperitoneal perfusion therapy was simultaneously administered during systemic chemotherapy. All patients underwent abdominal ultrasonography to localize ascites, followed by puncture catheter insertion. According to patient tolerance, ascites were continuously or intermittently drained. Intraperitoneal perfusion therapy was performed after the peritoneal effusion was drained off.

Patient groups were as follows: (1) Control group: Patients were treated with intraperitoneal cisplatin perfusion at 40 mg/m² (Qilu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) (d1); and (2) RH-endostatin group: Patients were treated with intraperitoneal cisplatin perfusion at 40 mg/m² (d1) and RH-endostatin (Shandong Simcere Medgenn Bio-Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) (d1, 4, and 7 repeated three times for one cycle). Following perfusion and to ensure that drugs had come into complete contact with the peritoneal cavity, patients were requested to adjust their position every 15 minutes; and within 6 hours, the drainage tube was clamped for 24 hours following drug infusion. During intraperitoneal perfusion, blood pressure, heart rate, pulse, and respiration levels were observed. Evaluations were performed every second cycle until progressive disease (PD) or mortality.

Primary indicators included the efficacious control of ascites and improved OS, while secondary indicators were quality of life and adverse events. To ascertain ascites control, ascites levels were evaluated using B-ultrasound. According to World Health Organization ascites standards, efficacious ascites control is represented as follows: Complete remission (CR), disappeared ascites; partial remission (PR), ascites numbers have significantly decreased by > 50% (≥ 4 weeks); stable disease (SD), ascites numbers have decreased by < 50% or increased but not by > 25%; and PD, ascites numbers have increased by > 25%. The overall remission rate (ORR) was calculated as follows: ORR = (CR + PR)/total cases × 100%; the disease control rate (DCR) was calculated as follows: DCR = (CR + PR + SD)/total cases × 100%, as previously described[11]. OS rates were determined from the time of treatment to mortality. To assess quality of life, the KPS was recorded as follows: Significant improvement (subtraction between pre-treatment KPS and KPS treatment ≥ +20), improvement (+10 to 19), unaltered (+10 to -10), and decreased (≥ -10). Improvement rates in the quality of life were calculated as follows: Quality of life = (significant improvement + improvement) cases/total cases × 100%. Adverse events (including chemotherapy and anti-vascular specific toxicity) were based on National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) (V.4.0)[12].

All patients were followed up via telephone or hospitalization. The median follow-up time for patients was 17 months. All patients were followed-up every 3 months until their demise. Routine blood and blood biochemistry analyses, ascites volume measurements, and B-ultrasounds were performed at each visit. An abdominal or pelvic CT scan was performed every 3-6 months. The last follow-up was performed in October 2024.

Categorical data differences were estimated using χ² tests. OS was determined using the Kaplan-Meier method, and log-rank tests were used to determine significance. Univariate survival analysis and multivariate analysis were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model to estimate independent OS risk factors. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS Statistics 25 software (IBM Corp.). A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Of the 120 patients who were examined for study inclusion, 115 were eligible to participate. Of these, 56 patients were assigned to the control group, while 59 were assigned to the RH-endostatin group. Median patient age at the time of diagnosis was 59.4 years (range, 36-79 years). The overall gender composition was 73 (63.5%) males and 42 (36.5%) females. Patients were grouped according to tumor location: 37 patients (32.2%) had tumors in the lower 1/3 of the stomach, 32 (27.8%) had tumors in the middle 1/3 of the stomach, and 46 (40.0%) had tumors in the upper 1/3 of the stomach. The differentiation degree was as follows: 41 patients (35.7%) had well/moderate differentiation and 74 (64.3%) had poor differentiation. Patients were also grouped according to ascites levels: 17 patients (14.8%) had small effusions, 34 (29.6%) had moderate effusions, and 64 (55.6%) had massive effusions. PM composition was as follows: 21 patients (18.3%) had oligo-metastases and 94 (81.7%) had multiple metastases. No significant differences in these characteristics were recorded between the groups (Table 1).

| Variables | Total (n = 115) | Control group (n = 56) | RH-endostatin group (n = 59) | χ2 | P value |

| Sex | 0.045 | 0.832 | |||

| Male | 73 (63.5) | 35 (62.5) | 38 (64.4) | ||

| Female | 42 (36.5) | 21 (37.5) | 21 (35.6) | ||

| Age (59.4 ± 10.2 years) | 0.475 | 0.491 | |||

| ≤ 60 | 64 (55.7) | 33 (58.9) | 31 (52.5) | ||

| > 60 | 51 (44.3) | 23 (41.1) | 28 (47.5) | ||

| Location of tumor | 0.036 | 0.982 | |||

| Lower 1/3 | 37 (32.2) | 18 (32.2) | 19 (32.2) | ||

| Middle 1/3 | 32 (27.8) | 16 (28.5) | 16 (27.1) | ||

| Upper 1/3 | 46 (40.0) | 22 (39.3) | 24 (40.7) | ||

| Degree of differentiation | 0.141 | 0.707 | |||

| Well/moderate | 41 (35.7) | 19 (34.0) | 22 (37.3) | ||

| Poor | 74 (64.3) | 37 (66.0) | 37 (62.7) | ||

| Amount of ascites | 1.173 | 0.556 | |||

| Small | 17 (14.8) | 7 (12.5) | 10 (16.9) | ||

| Moderate | 34 (29.6) | 15 (26.8) | 19 (32.2) | ||

| Massive | 64 (55.6) | 34 (60.7) | 30 (50.8) | ||

| Peritoneal metastases | 1.794 | 0.180 | |||

| Oligo | 21 (18.3) | 13 (23.2) | 8 (13.6) | ||

| Multiple | 94 (81.7) | 43 (76.8) | 51 (86.4) | ||

In the control group, CR cases numbered 8 (14.3%), PR cases numbered 20 (35.7%), SD cases numbered 12 (21.4%), and PD cases numbered 16 (28.6%). The ORR was 50.0% and the DCR was 74.5%. In the RH-endostatin group, CR cases numbered 11 (18.6%), PR cases numbered 30 (50.8%), SD cases numbered 8 (13.7%), and PD cases numbered 10 (16.9%). The ORR was 71.4% and the DCR was 83.1%. The ORR in the RH-endostatin group was significantly superior to that in the control group (P = 0.033), while no statistically significant difference in DCR was recorded between the groups (P = 0.136) (Table 2).

| Variables | Total (n = 115) | Control group (n = 56) | RH-endostatin group (n = 59) | χ2 | P value |

| CR | 19 (16.5) | 8 (14.3) | 11 (18.6) | ||

| PR | 50 (43.5) | 20 (35.7) | 30 (50.8) | ||

| SD | 20 (17.4) | 12 (21.4) | 8 (13.7) | ||

| PD | 26 (22.6) | 16 (28.6) | 10 (16.9) | ||

| ORR | 69 (60.0) | 28 (50.0) | 41 (69.4) | 4.548 | 0.033 |

| DCR | 89 (77.4) | 40 (71.4) | 49 (83.1) | 2.218 | 0.136 |

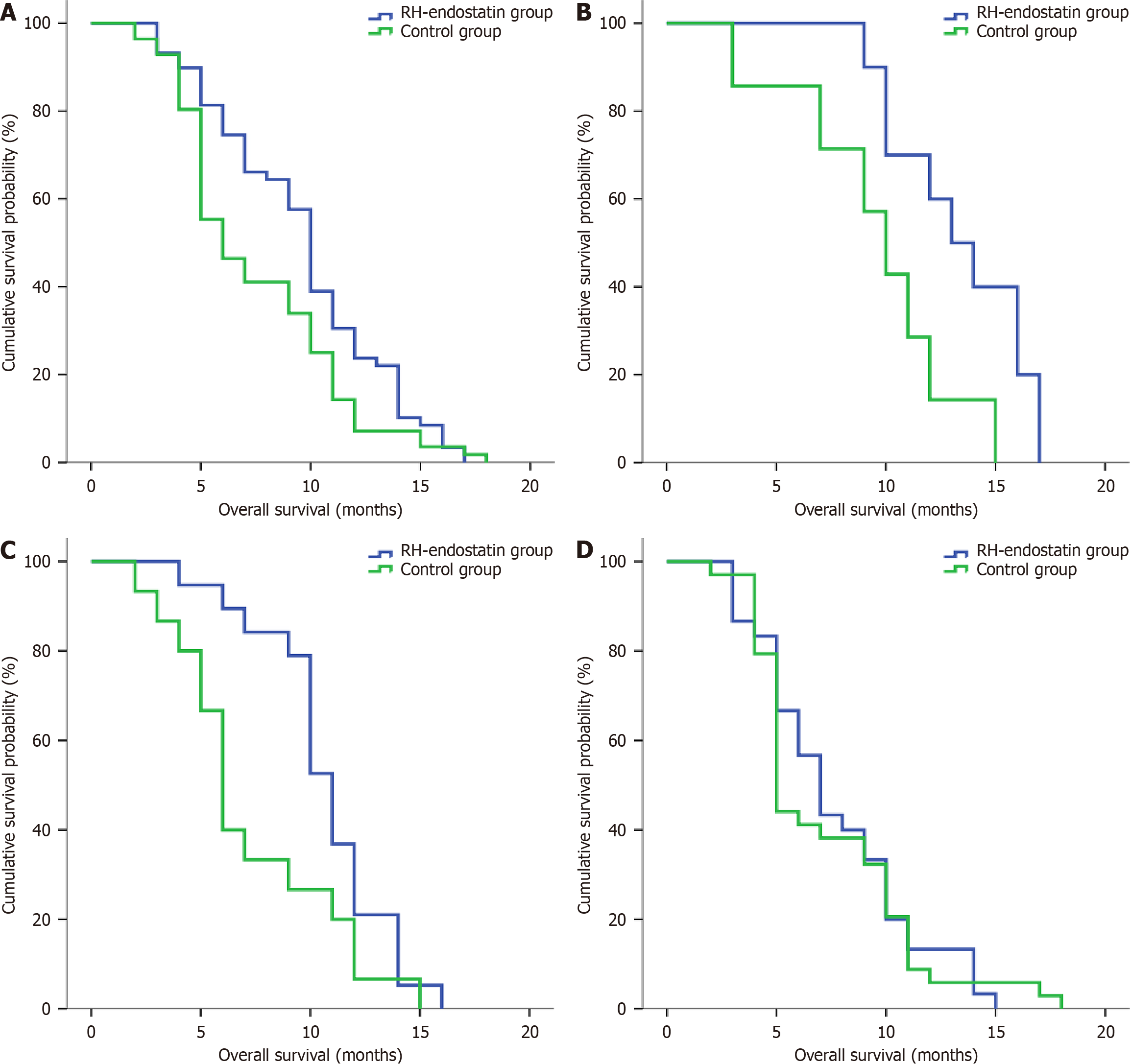

Patients in the control group had significantly lower OS rates when compared with patients in the RH-endostatin group

Univariate analysis revealed significant associations between OS and ascites levels [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.396; P = 0.005], PMs (HR = 0.604; P = 0.033), and treatment methods (HR = 1.516; P = 0.028). However, no association with sex, age, tumor location, or the differentiation degree was detected (P > 0.05). Significant variables from univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis; PMs (HR = 0.611; P = 0.042) and treatment methods (HR = 1.516; P = 0.036) were identified as independent OS factors (Table 3).

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR value (95%CI) | P value | HR value | P value | |

| Sex (male vs female) | 0.893 (0.606-1.316) | 0.893 | ||

| Age (≤ 60 vs > 60 years) | 0.956 (0.657-1.391) | 0.814 | ||

| Location of tumor (lower 1/3 vs middle 1/3 vs upper 1/3) | 1.077 (0.866-1.339) | 0.505 | ||

| Degree of differentiation (well/moderate vs poor) | 1.460 (0.992-2.147) | 0.055 | ||

| Amount of ascites (small vs moderate vs massive) | 1.396 (1.108-1.758) | 0.005 | 1.263 (1.027-2.240) | 0.061 |

| Peritoneal metastases | 0.604 (0.379-0.961) | 0.033 | 0.611 (0.374-0.997) | 0.042 |

| (Oligo vs multiple) | ||||

| Treatment methods (control group vs RH-endostatin group) | 1.516 (1.045-2.198) | 0.028 | 1.516 (1.027-2.240) | 0.036 |

In the control group, significant improvements in KPS scores were identified in six patients (10.7%), improved scores occurred in 15 patients (26.8%), stable scores in 24 patients (42.9%), and decreased scores in 11 patients (19.6%); thus, the improvement rate was 37.5%. In the RH-endostatin group, significant improvements in KPS scores were identified in 10 patients (16.9%), improved scores occurred in 27 patients (45.8%), stable scores in 15 patients (25.4%), and decreased scores in seven patients (11.9%); thus, the improvement rate was 62.7%. It was evident that RH-endostatin patients experienced significantly superior improvement rates when compared with control patients (P = 0.033) (Table 4).

| Variables | Total (n = 115) | Control group (n = 56) | RH-endostatin group (n = 59) | χ2 | P value |

| Significantly improved | 16 (13.9) | 6 (10.7) | 10 (16.9) | ||

| Improved | 42 (36.5) | 15 (26.8) | 27 (45.8) | ||

| Stable | 39 (34.0) | 24 (42.9) | 15 (25.4) | ||

| Decreased | 18 (15.6) | 11 (19.6) | 7 (11.9) | ||

| Improvement rate | 58 (50.4) | 21 (37.5) | 37 (2.7) | 7.305 | 0.007 |

Using NCI-CTCAE (V.4.0) guidelines, hematological, non-hematological, and anti-vascular specific toxicity events were observed, evaluated, and recorded. All hematological and non-hematological toxicity cases were grades I-III, with no severe adverse events occurring in both groups. Hematological toxicity mainly consisted of leucopenia, while non-hematological toxicity was mainly nausea and vomiting. The RH-endostatin group showed no increase in chemotherapy toxicity when compared with the control group.

Anti-vascular specific toxicities in the RH-endostatin group were secondary hypertension, secondary proteinuria, hemorrhage, and chemical peritonitis. No statistically significant differences in anti-vascular specific toxicity were recorded between the groups (Table 5).

| Variables | Total (n = 115) | Control group (n = 56) | RH-endostatin group (n = 59) | χ2 | P value |

| Hematological toxicity | 55 (47.8) | 30 (53.5) | 25 (42.3) | 1.444 | 0.230 |

| Leucopenia | 35 (30.4) | 19 (33.9) | 16 (27.1) | ||

| Anemia | 8 (7.0) | 5 (8.9) | 3 (5.1) | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | 12 (10.4) | 6 (10.7) | 6 (10.2) | ||

| Non-hematological toxicity | 58 (50.4) | 32 (57.1) | 26 (44.1) | 2.507 | 0.113 |

| Nausea, vomiting | 33 (28.7) | 18 (32.1) | 15 (25.4) | ||

| Constipation | 7 (6.1) | 4 (7.1) | 3 (5.1) | ||

| Tiredness | 12 (10.4) | 7 (12.5) | 5 (8.5) | ||

| Liver dysfunction | 6 (5.2) | 3 (5.4) | 3 (5.1) | ||

| Anti-vascular specific toxicity | 14 (12.1) | 9 (15.2) | 5 (8.5) | 1.566 | 0.2611 |

| Secondary hypertension | 2 (1.7) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | ||

| Secondary proteinuria | 4 (3.5) | 3 (5.4) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| Hemorrhage | 3 (2.6) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| Chemical peritonitis | 5 (4.3) | 2 (3.6) | 3 (5.1) |

The peritoneum is the most frequent metastasis site in patients with advanced-stage GC; 14%-43% of patients with primary GC are diagnosed with PM, and 35% of patients with recurrence and metastasis are diagnosed with PM following curative surgery and chemotherapy[13]. The peritoneal dissemination of tumor cells may cause excessive fluid accumulation in the peritoneal cavity. The main causes of malignant ascites may be lymphatic blockage, increased peritoneal capillary permeability, or disturbed lymphatic reflux. Ascites in the abdominal cavity are directly related to abdominal pain, gastrointestinal dysfunction, and tachycardia. Systemic chemotherapeutic drugs cannot effectively infiltrate the peritoneal cavity due to the peritoneal-plasma barrier, while a disordered blood supply in PM cancer also has critical roles in this process. Additionally, repeated ascites drainage may cause cachexia, and nutrients such as protein and fat-soluble vitamins can be lost after drainage, which may severely affect antitumor efficacy.

The prognosis of patients with GC and malignant ascites is poorer when compared with those without ascites[14]. Therefore, strategies reducing ascites are critical for treating patients with GC and PM plus ascites. Intraperitoneal perfusion therapy is a vital local treatment and has been commonly used to treat PM in different solid tumor types; it improves antitumor effects by increasing local drug concentrations in the abdominal cavity[5]. Intraperitoneal perfusion following ascites drainage using CT or B-ultrasound scans is a widely used treatment method. Intraperitoneal perfusion therapy can also prolong the survival of patients with GC and PM[15]. The PHOENIX-GC trial demonstrated the superiority of intraperitoneal paclitaxel plus systemic chemotherapy for the survival of patients with GC and PM with or without ascites. However, no standard recommended intraperitoneal perfusion drugs exist for GC[16]. Although several studies have investigated intraperitoneal drug perfusion for treating GC with ascites, the number of studies comparing efficacy outcomes between multiple treatments is limited, and results have been inconsistent[11]. Intraperitoneal chemotherapeutic drug perfusion remains the mainstay.

Cisplatin, which is included in the first generation of platinum-based drugs, has been widely used in clinical practice; it penetrates tumor surfaces and directly kills tumor cells; is easily absorbed by peritoneal capillaries to exert cytotoxic effects, and its effectiveness has been proven in studies[17]. However, some patients with advanced-stage GC or with GC and cachexia cannot tolerate the adverse events associated with traditional chemotherapy. Therefore, identifying intraperitoneal perfusion drugs with low toxicity that can effectively treat patients with GC and malignant ascites is urgent.

Angiogenesis has crucial roles in tumor occurrence and development, with anti-angiogenic therapy a key component in antitumor therapeutics. RH-endostatin is a short-term angiogenesis inhibitor; it directly inhibits vascular endothelial cell proliferation via multiple tumor targets[18], and exerts antitumor effects through vascular normalization. It has been shown that systemic chemotherapy with intravenous RH-endostatin injection may be clinically beneficial for several solid tumors[8]. It was previously reported that RH-endostatin effectively inhibited GC cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis in vitro[19]. Yao et al[20] evaluated the clinical effectiveness of RH-endostatin and oxaliplatin chemotherapy in patients with advanced-stage GC, and found that the combination exerted therapeutic benefits and was associated with improved survival rates and low adverse reactions. In recent years, it was reported that malignant serous cavity effusion and pleural or PM nodes had higher vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels; therefore, anti-VEGF pathway drugs (e.g., bevacizumab or RH-endostatin) could reduce the development of malignant cavity effusion[9]. In a mouse PM model, peritoneal RH-endostatin injection downregulated VEGF and its receptor; and furthermore, effectively controlled malignant ascites formation in mice[21]. In a recent clinical meta-analysis, intraperitoneal/pleural endostatin effusion alone or in combination with platinum effectively controlled malignant cavity effusion, and significantly prolonged the time to disease progression[9]. However, the value of intraperitoneal RH-endostatin perfusion in GC with ascites remains unclear. Previous retrospective studies have emphasized the short-term effectiveness of such perfusions in GC; however, only a limited number of studies have examined its effects on prognosis outcomes[22-24].

To explore the value of intraperitoneal RH-endostatin perfusion in patients with GC and malignant ascites, this double-blind clinical trial was designed to examine the efficacy of ascites control, survival, quality of life, and adverse events in patients with GC, and the possible factors influencing prognosis. We included 115 patients with GC and malignant ascites. Based on different intraperitoneal perfusion drugs, patients were divided into the group treated with an intraperitoneal perfusion of cisplatin alone (control group) and the group treated with an intraperitoneal perfusion of both cisplatin and RH-endostatin (RH-endostatin group). In terms of ascites control efficacy, the ORR in the control group was significantly lower when compared with the RH-endostatin group; RH-endostatin and cisplatin exerted synergistic effects in controlling ascites and inhibiting PM. However, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Ling et al[24] hypothesized that VEGF-induced KDR/Flk-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in endothelial cells could be inhibited by RH-endostatin, and that the drug exerted anti-angiogenic effects in peritoneal tissue.

In terms of prognostic value, treatment methods were identified as independent OS factors in patients. Control group patients had lower OS rates than those in the RH-endostatin group. To identify the most suitable patients, OS differences were analyzed in relation to different ascites levels. We observed that patients in the RH-endostatin group with small and moderate ascites volumes had significantly improved OS rates. Patients with GC and a massive ascites volume did not benefit from intraperitoneal RH-endostatin perfusion. It was considered that in such patients with massive ascites volumes, often with multiple PM and a large tumor burden, anti-angiogenesis therapy would result in low tumor control efficacy. In terms of quality of life, the control group had significantly lower improvements when compared with the RH-endostatin group. Hematological and non-hematological toxicity events were also observed and acceptable in both groups. The RH-endostatin group did not exhibit any increased toxicity when compared with the control group. Furthermore, anti-angiogenesis drug side effects were specifically observed in the RH-endostatin group, with no significant differences in secondary hypertension, secondary proteinuria, hemorrhage, and chemical peritonitis. Intraperitoneal RH-endostatin perfusion significantly improved the quality of life in patients with GC and ascites, with less toxicity.

Our study had some limitations. For example, enrolled patients with GC and PM were diagnosed by CT scan, and patients did not undergo laparoscopic examination. This led to a low proportion of peritoneal oligo-metastases. We also did not explore the underlying molecular interactions between RH-endostatin and cisplatin; however, these will be studied in the future.

We showed that intraperitoneal RH-endostatin perfusion improved treatment efficacy and prolonged prognosis outcomes in patients with GC and malignant ascites. This approach may benefit clinical applications in treating GC.

| 1. | Zhang J, Qi Z, Ou W, Mi X, Fang Y, Zhang W, Yang Z, Zhou Y, Lin X, Hou J, Yuan Z. Advances in the treatment of malignant ascites in China. Support Care Cancer. 2024;32:97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huang XZ, Pang MJ, Li JY, Chen HY, Sun JX, Song YX, Ni HJ, Ye SY, Bai S, Li TH, Wang XY, Lu JY, Yang JJ, Sun X, Mills JC, Miao ZF, Wang ZN. Single-cell sequencing of ascites fluid illustrates heterogeneity and therapy-induced evolution during gastric cancer peritoneal metastasis. Nat Commun. 2023;14:822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Senthil M, Dayyani F. Role of Iterative Normothermic Intraperitoneal Paclitaxel Combined with Systemic Chemotherapy in the Management of Gastric Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:694-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bhutiani N, Grotz TE, Concors SJ, White MG, Helmink BA, Raghav KP, Taggart MW, Beaty KA, Royal RE, Overman MJ, Matamoros A, Scally CP, Rafeeq S, Mansfield PF, Fournier KF. Repeat Cytoreduction and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Recurrent Mucinous Appendiceal Adenocarcinoma: A Viable Treatment Strategy with Demonstrable Benefit. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:614-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wahba R, Schmidt T, Buchner D, Wagner T, Bruns CJ. [Surgical treatment of pseudomyxoma peritonei-Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy]. Chirurgie (Heidelb). 2023;94:840-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang B, Zhong C, Liao Z, Wang H, Cai X, Zhang Y, Wang J, Wang T, Yao H. Effectiveness and safety of human type 5 recombinant adenovirus (H101) in malignant tumor with malignant pleural effusion and ascites: A multicenter, observational, real-world study. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14:3051-3057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Anakha J, Dobariya P, Sharma SS, Pande AH. Recombinant human endostatin as a potential anti-angiogenic agent: therapeutic perspective and current status. Med Oncol. 2023;41:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhu J, Chen G, Niu K, Feng Y, Xie L, Qin S, Wang Z, Li J, Lang S, Zhuo W, Chen Z, Sun J. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human endostatin during peri-radiotherapy period in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2022;18:1077-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jie Wang X, Miao K, Luo Y, Li R, Shou T, Wang P, Li X. Randomized controlled trial of endostar combined with cisplatin/ pemetrexed chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced malignant pleural effusion of lung adenocarcinoma. J BUON. 2018;23:92-97. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Wei H, Qin S, Yin X, Chen Y, Hua H, Wang L, Yang N, Chen Y, Liu X. Endostar inhibits ascites formation and prolongs survival in mouse models of malignant ascites. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:2694-2700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Oriuchi N, Nakajima T, Mochiki E, Takeyoshi I, Kanuma T, Endo K, Sakamoto J. A new, accurate and conventional five-point method for quantitative evaluation of ascites using plain computed tomography in cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:386-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liu YJ, Zhu GP, Guan XY. Comparison of the NCI-CTCAE version 4.0 and version 3.0 in assessing chemoradiation-induced oral mucositis for locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:554-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li Z, Wang J, Wang Z, Xu Y. Towards an optimal model for gastric cancer peritoneal metastasis: current challenges and future directions. EBioMedicine. 2023;92:104601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zheng LN, Wen F, Xu P, Zhang S. Prognostic significance of malignant ascites in gastric cancer patients with peritoneal metastasis: A systemic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3247-3258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Coccolini F, Cotte E, Glehen O, Lotti M, Poiasina E, Catena F, Yonemura Y, Ansaloni L. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer. Meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:12-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ishigami H, Fujiwara Y, Fukushima R, Nashimoto A, Yabusaki H, Imano M, Imamoto H, Kodera Y, Uenosono Y, Amagai K, Kadowaki S, Miwa H, Yamaguchi H, Yamaguchi T, Miyaji T, Kitayama J. Phase III Trial Comparing Intraperitoneal and Intravenous Paclitaxel Plus S-1 Versus Cisplatin Plus S-1 in Patients With Gastric Cancer With Peritoneal Metastasis: PHOENIX-GC Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1922-1929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Murata S, Yamamoto H, Naitoh H, Yamaguchi T, Kaida S, Shimizu T, Shiomi H, Naka S, Tani T, Tani M. Feasibility and safety of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy using 5-fluorouracil combined with cisplatin and mitomycin C in patients undergoing gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:1159-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li K, Shi M, Qin S. Current Status and Study Progress of Recombinant Human Endostatin in Cancer Treatment. Oncol Ther. 2018;6:21-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang YB, Liu JH, Song ZM. Effects of recombinant human endostatin on the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human gastric cancer cell line MGC-803. Biomed Rep. 2013;1:77-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yao J, Fan L, Peng C, Huang A, Liu T, Lin Z, Yang Q, Zhang T, Ma H. Clinical efficacy of endostar combined with chemotherapy in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in gastric cancer: results from a retrospective study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:70788-70797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jia L, Ren S, Li T, Wu J, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Wu J, Liu W. Effects of Combined Simultaneous and Sequential Endostar and Cisplatin Treatment in a Mice Model of Gastric Cancer Peritoneal Metastases. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:2920384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhan Z, Wang X, Yu J, Zheng J, Zeng Y, Sun M, Peng L, Guo Z, Chen B. Intraperitoneal infusion of recombinant human endostatin improves prognosis in gastric cancer ascites. Future Oncol. 2022;18:1259-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liang J, Dai W, Li Z, Liang X, Xiao M, Xie C, Li X. Evaluating the efficacy and microenvironment changes of HER2 + gastric cancer during HLX02 and Endostar treatment using quantitative MRI. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ling Y, Yang Y, Lu N, You QD, Wang S, Gao Y, Chen Y, Guo QL. Endostar, a novel recombinant human endostatin, exerts antiangiogenic effect via blocking VEGF-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of KDR/Flk-1 of endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:79-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |