Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.103113

Revised: January 7, 2025

Accepted: February 14, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 133 Days and 15.1 Hours

Colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) ranks second in terms of cancer-related deaths. We found that fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4), which is related to cell adhe

To verify the possibility of using FABP4 as a biomarker for COAD.

A total of 453 COAD tissue samples, along with 41 normal tissue samples, were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas database. The difference in FABP4 expression between COAD tissues and normal tissues was analyzed, and the results were verified by immunohistochemistry. The WGCNA algorithm links FABP4 expression with an enrichment analysis and with immune cell infiltration pathways. The biological functions of FABP4 and its coexpressed genes were explored through enrichment analyses. The ESTIMATE, CIBERSORT and ssGSEA methods were used for the immune infiltration analysis. Finally, risk scores were calculated by a Cox analysis. A nomogram was constructed by combining risk scores with routine clinicopathological factors. We assessed the accuracy of survival predictions based on the C-index. The C-index ranges from 0.5 to 1.0, and in general, a C-index value greater than 0.65 indicates a reasonable estimate. The results were validated using the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database.

FABP4 was significantly differentially expressed in COAD. It is a promising auxiliary biomarker for screening and diagnosis. Enrichment analyses suggested that FABP4 may influence the invasion and progression of COAD through cell adhesion. The immunological analysis revealed that FABP4 expression in COAD was significantly positively correlated with immune cell infiltration. Moreover, a nomogram to predict the survival of COAD patients was successfully constructed by integrating the calculated risk scores of 15 candidate genes and routine clinicopathological factors. This nomogram could effectively predict 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival (C-index = 0.786) and was verified (C-index = 0.73).

This study established FABP4 as an effective biomarker for screening, assisting in the diagnosis and determining the prognosis.

Core Tip: Fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4) can be used as a biomarker of colon adenocarcinoma (COAD). Based on this, a nomogram was constructed to effectively predict the survival of COAD patients. FABP4 influences COAD invasion and progression through cell adhesion and immune-related pathways.

- Citation: Zhang Y, Zhu WL, Wu M, Gao TY, Hu HX, Xu ZY. Using bioinformatics methods to elucidate fatty acid-binding protein 4 as a potential biomarker for colon adenocarcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(4): 103113

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i4/103113.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.103113

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, accounting for approximately 10% of all cancers, and ranks second in mortality[1,2]. Metastasis occurs in 50%-60% of CRC patients[3] with a five-year overall survival (OS) rate of less than 20%[4,5]. Colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), the main type of CRC, develops from gene mutations in adenomatous lesions[6]. Previous studies have shown that a tumor immune microenvironment analysis has the potential to predict and guide immunotherapy[7,8]. Many studies have shown that fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4) is inextricably related to tumor microenvironment (TME) disorders, and that the occurrence of colon cancer is inextricably related to TME disorders[9]. New sensitive and specific immunotherapy markers need further exploration due to tumor heterogeneity. Accordingly, novel and effective diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for the early screening and personalized treatment of COAD patients are needed.

FABP4 is an important member of the fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) family, and is found in adipocytes, endothelial cells, and immune cells[10]; and acts as a link between tumor cells and components of the TME[11]. FABP4 plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of various metabolic pathologies and has been shown to be abnormally expressed in several cancer types[11,12]. FABP4 has been identified as a biomarker and therapeutic target in tumors[11].

Recent studies have described the influence of FABP4 on tumor malignancy, such as its ability to drive tumor resistance to apoptosis and promote recurrence[13]. FABP4 enhances lipid transport and activates multiple signaling pathways involved in tumor transformation, proliferation, metastasis, and treatment resistance[14]. Several preliminary studies have shown a relationship between FABP4 expression and the immune status of patients with CRC[15], but the screening, diagnostic and prognostic value of FABP4 in COAD have not been extensively discussed.

Previous studies have shown an inextricable link between FABP4 and COAD, but no comprehensive bioinformatics studies have been conducted[9]. The aim of this study was to explore the combined value of FABP4 as a potential biomarker for COAD. We analyzed the expression levels of FABP4 and clinicopathological factors of COAD and normal tissues using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) databases, identified FABP4 as an adverse prognostic factor, and performed a functional enrichment analysis and immune infiltration analysis. Our findings indicate that cell adhesion is the main biological process (BP) associated with FABP4, suggesting that it plays a role in promoting the occurrence and development of COAD through this process. A significant positive correlation between FABP4 expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) was detected, indicating that FABP4 promotes the occurrence and development of COAD through immune-related pathways. Finally, a risk score was calculated for FABP4 and its OS-related coexpressed gene set, and a nomogram was constructed by combining conventional clinicopathological factors. It is a good predictor of the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival of COAD patients. This comprehensive analysis establishes FABP4 as a biomarker for COAD and improves our understanding of the molecular function (MF) of FABP4, providing new insights into the onset and progression of COAD.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wannan Medical College [Wuhu, China; ethical approval number: (2023) 215], and written informed consent was obtained from COAD patients to perform immunohistochemical staining for FABP4 (experiment date: December 2023). The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: Had COAD (aged 30 to 90 years), male and female half. The exclusion criteria were pregnant women and nursing mothers. The paired COAD tissue and paracancerous tissue samples were obtained from the same subject. Ten patients with COAD diagnosed at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Wannan Medical College were randomly selected for immunohistochemical staining, and tumor tissue and adjacent tissue samples were collected from each patient. All the samples were completely deidentified before the start of the immunohistochemical staining experiment. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were used for the immunohistochemical analysis of FABP4 expression according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, after partial paraffin dewaxing and antigen retrieval with citrate buffer, 3% hydrogen peroxide was used to block endogenous peroxidase activity. After blocking with serum, the sections were incubated with a primary antibody (Affinity Biosciences, Cat. No. DF6035) at 4 °C overnight and then with a secondary antibody for two hours, followed by DAB color development and hematoxylin staining. Images were captured at × 100 and × 200 magnifications using a Leica upright microscope (Germany). The positive intensity of immunostaining was scored as 0 points (colorless), 1 point (light yellow), 2 points (brown yellow), or 3 points (dark brown). According to the mean percentage of positive tumor cells, the ratio of positive cells to tumor cells was < 10%, 10%-50%, 50%-75%, or > 75%. The scores ranged from 1 to 4 points. The percentage of positive tumor cells and staining intensity were multiplied to produce a weighted score: < 3 score (-), 3-5 score (+), 6-9 score (++), and > 9 score (+++). Scoring was performed in a double-blinded manner by two senior diagnostic physicians[16].

The study cohort comprised TCGA COAD database, which consists of 453 samples of COAD tumor tissue and 41 normal tissue samples. Raw RNA-seq data (counts) and processed RNA-seq data (FPKM), along with clinicopathological factor and survival status data, were obtained from the University of California, Santa Cruz Xena platform (https://xena.ucsc.edu).

The samples included patients with comprehensive clinical information, including age; sex; T, N, and M classification; tumor stage; and vital statistics. Data were analyzed and processed using R version 4.2.2 and the relevant R packages. The raw RNA-seq data were subjected to analysis of variance and the processed RNA-seq data (FPKM) were subjected to further analysis.

This study examined the categorization of FABP4 mRNA expression levels in COAD samples and normal colon samples. The analysis involved ranking patients in the COAD database based on their mRNA expression level and determining the H-FABP4 group and L-FABP4 group based on the median value of FABP4 expression.

The R software package DESeq2 was used to compare expression profile data (counts) and identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between COAD samples and normal samples in TCGA database[17]. The threshold for determining DEGs was set at |log2 fold change| > 1.5, with a P value < 0.05 after adjustment.

The R package WGCNA was subsequently used to analyze the DEGs[18]. A power of two was selected to ensure that the constructed coexpression network approached a scale-free distribution. The DEGs were divided into ten different gene modules, with a minimum module size of 30. Correlations of the modules with the matrix score, immune score, estimated score, tumor purity, and FABP4 expression were computed.

The module with the highest absolute significance was identified as the key module, as determined based on module membership degree (representing the Pearson correlation coefficient between genes and modules, |module membership (MM)| > 0.6) and gene significance (representing the Pearson correlation coefficient between genes and clinical parameters, |gene significance (GS)| > 0.5). Ultimately, a total of 146 hub genes were obtained.

The DAVID tool (https://david-d.ncifcrf.gov/) was used to conduct Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses of the key modules identified via WGCNA.

Furthermore, for the FABP4 expression groups (H-FABP4 and L-FABP4), a gene variation analysis was performed according to the criteria of a |log2 fold change| > 1 and a P value < 0.05 after adjustment. A total of 1358 genes were selected for the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the clusterProfiler package (version 4.6.0) in R to explore the biological functions of FABP4 in COAD[19].

Simultaneously, gene set variation analysis (GSVA) was applied to examine the relationships between each patient and the biological functions. The biological functions of the genes identified via GSEA were obtained from the GSEA Molecular Signatures Database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp), and their scores were calculated using the R package GSVA (version 1.46.0). A heatmap of the enrichment results for COAD patients and the biological functions was generated using the pheatmap package in R.

The correlations between the expression of FABP4 and cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) were analyzed using the Pearson algorithm (63 major CAMs were selected according to the four major groups of CAMs)[20-22], with P < 0.05 and an absolute value of the correlation coefficient |R| > 0.4.

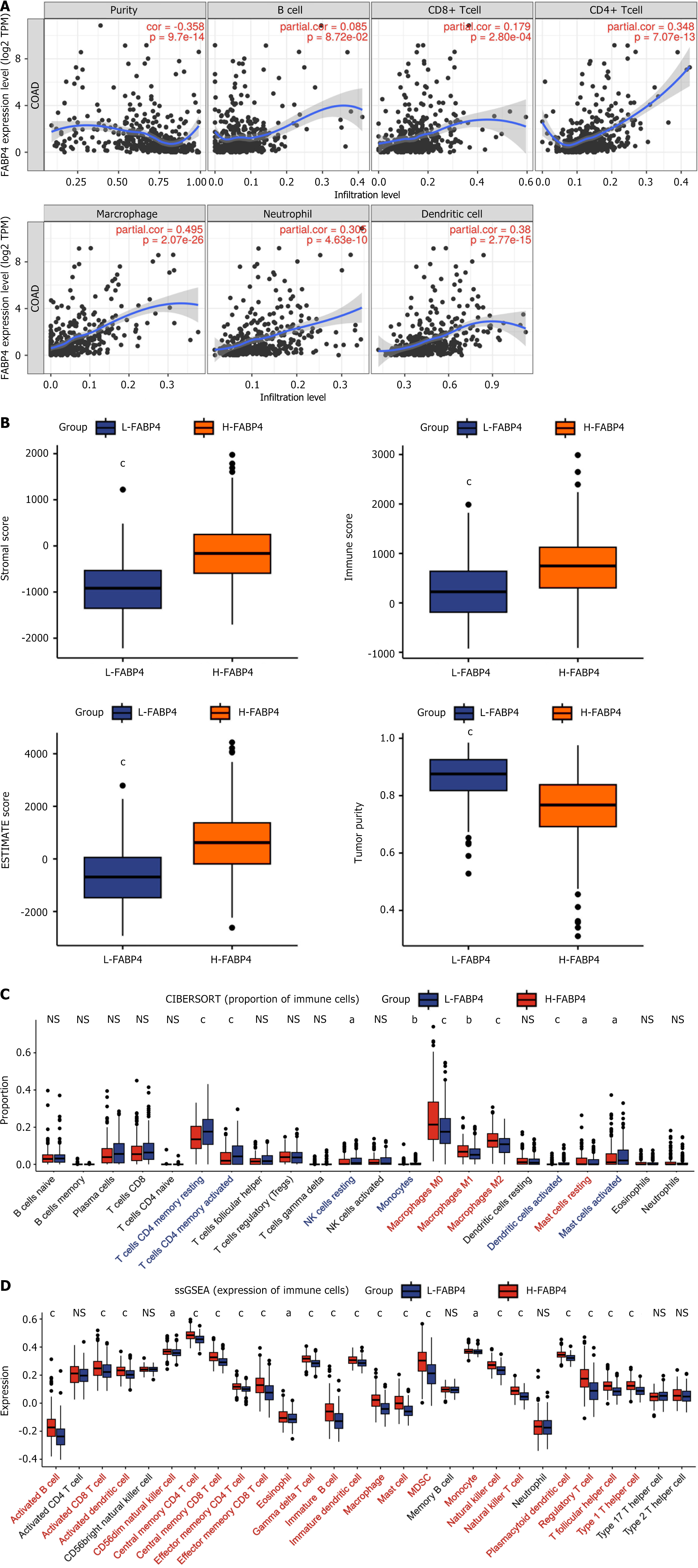

The TIMER online database (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) can be utilized to conduct a comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells[23]. This approach allows the calculation of FABP4 subtype expression and the levels of six different types of tumor-infiltrating immune cells [B cells, CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (DCs)] and their correlations with tumor purity.

In this study, the R package estimate was used to evaluate various aspects of the TME in COAD patients, including the stromal score, immune score, ESTIMATE score, and tumor purity[24]. CIBERSORT is a deconvolution algorithm that enables estimation of the proportions of 22 distinct immune cell types within each sample from COAD patients[25]. Single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA) is a quantitative method used to assess the levels of infiltration of 28 immune cell types based on their correlation with FABP4 expression[26]. In this analysis, the R package GSVA was used to calculate correlations and determine the degree of infiltration for each immune cell type[27].

Coexpressed genes with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.65 with FABP4 were selected for the Cox analysis, and the gene sets significantly associated with OS were selected to calculate the risk score.

The formula was developed as follows: Risk score = ∑ [c (genes) × Exp (genes)] where coef represents the coefficient of each gene in the Cox regression analysis and Exp represents the expression level of each gene.

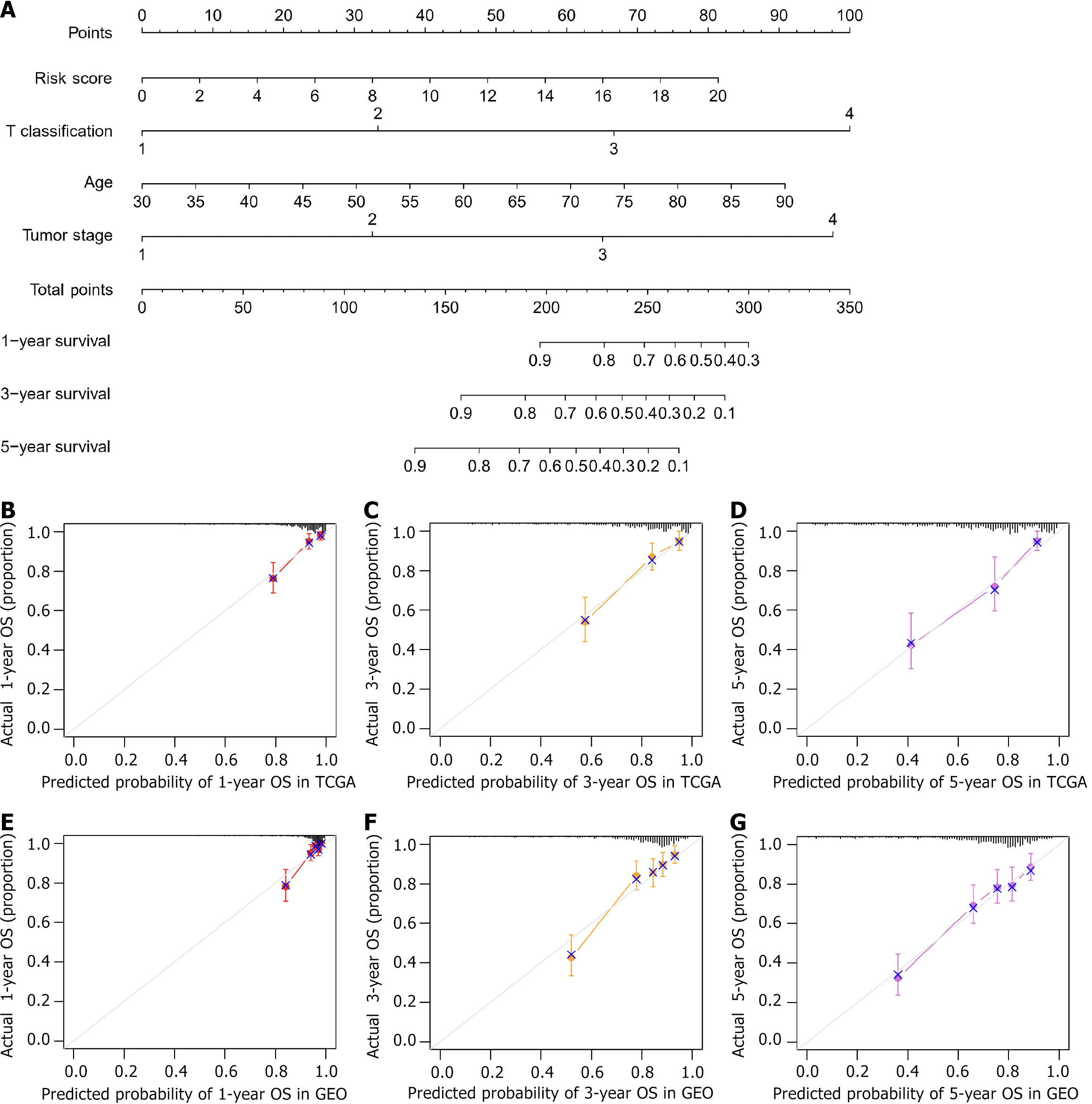

A nomogram was constructed via the rms package combined with the risk score and routine clinicopathological factors. The nomogram could effectively predict 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival. Calibration curves and the C-index were used to measure the accuracy of the nomogram. The calibration curves showed the consistency between the predicted OS and the actual OS. A C-index greater than 0.65 indicates a reasonable estimate[28].

For this study, we downloaded the expression matrix for RNA-seq data, clinicopathological factor data, and survival status data from the GSE39582 dataset from the National Center for Biotechnology Information GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). The GSE39582 cohort included 585 patients with stage I to IV COAD who underwent surgery between 1987 and 2007 at seven centers. The dataset consists of 566 COAD tissue samples (tumor) and 19 normal tissue samples (normal)[29]. We specifically included patients whose clinical information was complete in the analysis.

All clinical data, including age, sex, OS, tumor stage, T classification, N classification, and metastasis, along with the genetic expression matrix, were statistically analyzed using R version 4.2.2 and several R packages, such as tidyverse, DESeq2, ggplot2 and survminer. An unpaired t test was used to determine the significance of differences between two groups; one-way ANOVA was used to compare differences between three or more groups. Kaplan-Meier (K-M) curves were generated via the log-rank test to assess the significance of the difference in prognosis between the high FABP4 expression group and the low FABP4 expression group. Univariate and multifactorial analyses of OS were conducted with data from the TCGA to identify prognostic factors for COAD. The P value of the Pearson correlation analysis was corrected by the Bonferroni correction. For the immune infiltration analysis, P values are marked with asterisks. The notations used were "NS" for not statistically significant, aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, and cP < 0.001. A P value of less than 0.05 (with a 95%CI level) was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Compared with tissues in the normal control group, the tumor tissues in the experimental group presented significantly lower expression of the FABP4 mRNA (P < 0.001; Figure 1A). A receiver operating characteristic curve was generated to validate its reliability as a valuable tool for distinguishing COAD. The area under the curve was calculated to be 92.52% (95%CI: 90.13%-94.91%), indicating that FABP4 may serve as a highly effective tool to distinguish COAD (Figure 1B). Moreover, our immunohistochemical results revealed lower staining intensities in COAD tumor tissues than in adjacent noncancerous colon tissues, indicating lower protein expression in COAD (Figure 1C). Immunohistochemical scores are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

We assessed associations between FABP4 expression and various clinical factors, including age, sex, tumor stage, T stage, N stage, and metastasis. The results are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. We observed a significant increase in FABP4 expression in patients with an advanced tumor stage, advanced T classification, and advanced N classification.

Moreover, we conducted a subgroup analysis according to the tumor stage, T stage N stage, and metastasis. Interestingly, despite the low expression of FABP4 in COAD tumors, its expression gradually increased with increasing tumor stage. A comparative analysis of samples from different groups in TCGA database revealed that FABP4 was highly enriched in high-grade tumor stages (Supplementary Figure 1A), T stages (Supplementary Figure 1B), and N stages (Supplementary Figure 1C). Additionally, FABP4 was more highly expressed in metastatic COAD tumors. Although the trend in its expression was consistent across different stages, this difference was not statistically significant in TCGA dataset (Supplementary Figure 1D). These findings collectively suggest that FABP4 enrichment in COAD tissues is associated with increased malignancy.

Patients with varying levels of FABP4 expression presented distinct clinical and pathological features. As FABP4 expression increased, the tumor stage, T stage, and N stage exhibited nonuniform distributions. Additionally, the survival rate of patients exhibited a similar nonuniform distribution as the FABP4 expression level increased (Figure 2A).

A K-M survival analysis was conducted using TCGA database to investigate the prognostic value of FABP4 expression in COAD patients. The analysis revealed that the group with high FABP4 expression (H-FABP4) experienced significantly shorter OS than did the group with low FABP4 expression (L-FABP4) (P = 0.009; Figure 2B).

The univariate regression analysis and Cox regression analysis of TCGA data incorporating various established prognostic factors, such as the age at diagnosis, T stage, N stage, and disease type, showed that FABP4 was an independent prognostic factor (Table 1), with OS as the primary endpoint. The multivariate analysis revealed that FABP4 remained significant after adjusting for confounders. A hazard ratio (HR) of less than 1 was considered a good prognostic factor for COAD, whereas an HR greater than 1 was considered a poor prognostic factor for COAD.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| FABP4 expression | 1.175 (1.052-1.314) | 0.004a | 1.140 (1.015-1.280) | 0.03a |

| Age | 1.022 (1.004-1.040) | 0.01a | 1.028 (1.011-1.045) | 0.001a |

| T classification | 2.897 (1.934-4.339) | < 0.001b | 2.224 (1.463-3.380) | < 0.001b |

| N classification | 1.982 (1.572-2.499) | < 0.001b | 1.862 (1.478-2.346) | < 0.001b |

| Disease type | 1.149 (0.774-1.707) | 0.04a | 1.393 (0.938-2.068) | 0.10 |

A total of 3231 genes that were differentially expressed between COAD tissues and normal tissues were screened from TCGA to identify genes and modules associated with FABP4. A volcano plot and a heatmap (containing clustering relationships between genes) were generated to visually represent the DEGs (Figure 3A and B).

Subsequently, WGCNA was performed. The WGCNA parameters were adjusted, and the DEGs were organized into ten modules via the average linkage hierarchical clustering method (Figure 3C-E). Among these modules, the turquoise module comprised 1216 genes and presented the strongest correlation with FABP4 expression (Pearson’s correlation coefficient = 0.62, P < 0.001; Figure 3F).

A total of 146 genes were identified as hub genes in the turquoise module. These genes met the criteria of having an absolute module membership (MM) greater than 0.6 and an absolute gene significance (GS) greater than 0.5 (Figure 3G).

An analysis of the 146 hub genes in the blue module revealed that the cell adhesion pathway was the most prevalent. Specifically, the GO analysis of the BP, cellular component, and MF terms revealed "cell adhesion", "extracellular region", and "heparin binding", respectively, as the most significant terms (Figure 4A-C). Notably, "axon guidance" was identified as the most significant pathway in the KEGG analysis (Figure 4D).

Further investigation via GSEA was conducted to explore the mechanisms and functions of the 146 hub genes with the strongest correlation with FABP4 expression. The analysis revealed enrichment in several entries, including "cell-cell adhesion via plasma membrane adhesion molecules" and "cell adhesion" (Figure 4E).

The impact of FABP4 expression on BP terms and GSEA was evaluated in TCGA database to validate the results of the functional enrichment analyses. GSVA was utilized to determine functional enrichment scores based on their correlation with FABP4 expression. The results confirmed a significant positive correlation between FABP4 expression and cell adhesion (Figure 4F).

After the correlation coefficient was set, FABP4 was significantly correlated with 15 CAMs, arranged in descending order of correlation coefficients in the correlation chord diagram (Supplementary Figure 2A). Among them, an analysis of the expression levels of the top five CAMs (ITGA7, CDH19, CDH23, SELP, and PECAM1, P < 0.001) with correlation coefficients revealed that their expression levels in tumors were significantly downregulated similar to those of FABP4 (Supplementary Figure 2B-F).

WGCNA revealed a potential correlation between FABP4 expression and immune-related modules (Figure 3E), and an immune infiltration analysis of FABP4 was conducted to explore this result further. According to the TIMER analysis, CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and DCs were significantly positively correlated (P < 0.001) and tumor purity was significantly negatively correlated (P < 0.001) with FABP4 expression (Figure 5A).

ESTIMATE, CIBERSORT, and ssGSEA were conducted to verify these findings in two groups stratified according to the expression level of FABP4 in two groups: The high-expression group (H-FABP4) and the low-expression group (L-FABP4). The results of the ESTIMATE analysis revealed that the matrix score, immune score, and ESTIMATE score were higher in the H-FABP4 group than in the L-FABP4 group but that the tumor purity score was lower in the H-FABP4 group (Figure 5B). Further analysis revealed that the H-FABP4 group had greater proportions of macrophages and mast cells (Figure 5C). Moreover, ssGSEA revealed significant positive correlations between FABP4 expression and 22 of the 28 TIL subtypes in COAD (P < 0.05; Figure 5D). According to the preliminary findings of the TIMER analysis, FABP4 was associated with the immune cell infiltration in COAD. We further studied the relationship between FABP4 and a variety of TILs to verify this finding, and the results further expanded the findings of the TIMER analysis.

FABP4 and its coexpressed genes (correlation coefficient |r| > 0.65) were analyzed by Cox regression analysis. Fifteen genes that were significantly associated with OS were identified (FABP4, PRG4, CYP11A1, CLDN11, PTH1R, PPP1R1A, TUSC5, ABCA9, PDE1B, CILP, CIDEA, GPX3, MRAP, TNNT3, PP1R1A, and PCOLCE2). The risk score was calculated. When the survival analysis model was fitted with the risk score and clinicopathological factors from the TCGA, the risk score, T classification, age and tumor stage were used to construct a nomogram to predict the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival of COAD patients (Figure 6A), with a C-index = 0.786. The nomogram and actual observations in the calibration curve showed satisfactory overlap in the TCGA training cohort (Figure 6B-D), indicating optimal predictive accuracy.

Through our analysis of the GEO database, we determined that the expression level of FABP4 can be used to effectively distinguish between tumor tissues and normal tissues (Supplementary Figure 3A and B). The K-M survival analysis revealed a significantly shorter survival time for patients in the H-FABP4 group than for patients in the L-FABP4 group (Supplementary Figure 3C). Moreover, the enrichment analysis revealed that FABP4 is associated primarily with cell adhesion (Supplementary Figure 3D-G). The immune infiltration analysis revealed higher matrix, immune, and ESTIMATE scores for the H-FABP4 group than for the L-FABP4 group, although the tumor purity score was lower for the H-FABP4 group (Supplementary Figure 4A). Additionally, the H-FABP4 group presented greater proportions of macrophages and mast cells (Supplementary Figure 4B). FABP4 expression was significantly positively correlated with 24 of the 28 TIL subtypes in COAD (P < 0.05; Supplementary Figure 4C). Moreover, the nomogram calibration curve also showed good agreement between the predicted value and the actual value (Figure 6E-G), with a C-index = 0.73. These findings are consistent with our results based on TCGA dataset.

The incidence and mortality rates of CRC, particularly metastatic CRC, remain high, with an overall five-year survival rate of less than 20%. In recent years, the discovery of specific biomarkers and combinations has improved the accuracy of CRC screening and facilitated the development of targeted drugs. Moreover, many studies of TCGA-based biomarkers, such as single genes for a single cancer[30], gene sets for a single cancer[31], single genes for multiple cancers[32], and gene sets for multiple cancers[33], have been conducted. However, relatively few studies have investigated COAD biomarkers and their associated functions. Our study revealed that FABP4 affects the occurrence and development of COAD through cell adhesion and immune cell infiltration pathways, and is a potential biomarker for COAD. We found that FABP4 can assist in the diagnosis of COAD, as it is expressed at significantly lower levels in COAD tissues than in normal tissues. We further confirmed the diagnostic efficacy of FABP4 via our own immunohistochemical staining and GEO validation data. Additionally, we found that high expression of FABP4 is associated with an advanced tumor stage, T classification, and lymph node metastasis, suggesting that FABP4 promotes metastasis and acts as an adverse prognostic factor. Regression and survival analyses confirmed a significant negative correlation between FABP4 expression and the OS of COAD patients. Mouse experiments also support the hypothesis that inhibiting FABP4 can hinder the interaction between tumor cells and adipose tissue, leading to decreased tumor cell proliferation and metastasis and blood vessel growth in tumors[34,35]. These findings indicate the protumor role of FABP4 in COAD, and FABP4 was shown to be a potential biomarker for COAD.

Previous studies have shown that COAD and CAMs are closely related[36]. Our systematic study of the role of FABP4 in COAD revealed that FABP4 is involved in cell adhesion and immune cell infiltration. Altered cell adhesion often results in aggressive and migratory phenotypes in tumor cells[37], and FABP4 may impact the prognosis and survival of COAD patient through its influence on cell adhesion[37]. Studies indicate that FABP4 may produce energy through fatty acid oxidation in COAD, activating tumor cell metabolism and signaling pathways, which in turn enhance cell adhesion, migration, and invasion[35]. These results support our conclusion that FABP4 is significantly correlated with cell adhesion, indicating its potential role in promoting COAD invasion and spread via cell adhesion. Moreover, in recent decades, advancements in genomic research and the development of precision-targeted therapies have significantly improved the prognosis of patients with advanced CRC, including those with COAD[38]. CRC drugs targeting VEGF, EGFR, BRAFV600E, PDL1, and others are currently being used in first-line treatment or are included in clinical studies for CRC. Pan et al[39] found through immunohistochemistry that patients with COAD and elevated FABP4 expression had increased CD8 infiltration, suggesting that FABP4 is closely related to immune response and metastasis, and may be a potential therapeutic target for COAD. Our results revealed a significantly elevated ratio of macrophages to mast cells in the H-FABP4 group. FABP4 is expressed mainly in adipocytes, macrophages and endothelial cells[40-42], and FABP4 expression in macrophages can mediate the inflammatory response and cholesterol accumulation, which helps to provide a more favorable microenvironment for tumor growth. Cancer cells disrupt the integrity of the intestinal barrier by interacting with immune cells, stromal cells, and the extracellular matrix, which together form the TME[9]. The TME affects tumor progression, immunotherapy resistance, immune escape, and tumor invasion. High levels of M2 macrophage infiltration are associated with a poor prognosis, and mast cells are also involved in immune evasion in cancer[43,44]. These results suggest that FABP4 may promote the occurrence and development of COAD by suppressing immune function.

The predictive accuracy of the nomogram constructed in our research was a C-index of 0.786 in TCGA database and 0.73 in the verification analysis using the GEO database. These findings indicate that it can predict the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival of COAD patients well. The relevant literature has confirmed that FABP4 plays an important role in the prognostic assessment and survival prediction of COAD patients. Among them, based on FABP4-associated immunomodulators, the Chongqing Medical University team constructed a 2-immunomodulator signature to predict the prognosis of patients with COAD. The C-index of the nomogram they constructed in TCGA training set was 0.584, with no verification set[15]. The Miao et al[45] screened 12 immune genes, including FABP4, and constructed a nomogram to predict the survival of patients with COAD. The C-index of the nomogram was 0.77 in TCGA training set and 0.72 in the GEO verification set[45]. These findings further support the feasibility and value of FABP4 as a biomarker for COAD and indicate that the prediction model we constructed has better predictive accuracy.

However, our study has several limitations. First, this study lacked prospective clinical validation. The conclusions of the enrichment analysis and immune infiltration analysis should be verified in clinical trials. Previous studies used xenograft models of cancer. Our future studies that could validate these findings in patient-derived xenograft models or larger cohorts. Second, this study relied too heavily on retrospective datasets. Some clinicopathological factors in TCGA and GEO databases are incomplete, and thus the validation and application of the constructed nomogram for the prognostic value of FABP4 need to be further explored.

This study revealed that elevated FABP4 expression is strongly associated with COAD progression and a shortened survival time, indicating its potential as a biomarker for COAD. FABP4 promotes the invasion and metastasis of COAD cells by altering their adhesion characteristics and ultimately affects the prognosis and survival of COAD patients. A nomogram was constructed using the calculated risk scores of FABP4 and its coexpressed genes combined with clinicopathological factors to predict the survival of COAD patients. This study establishes the potential of FABP4 as a biomarker for COAD, provides a basis for further studies of FABP4, and provides new insights into cancer mechanisms.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64342] [Article Influence: 16085.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (175)] |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2279] [Cited by in RCA: 4610] [Article Influence: 4610.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Arain MA, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D, Farkas L, Garrido-Laguna I, Grem JL, Gunn A, Hecht JR, Hoffe S, Hubbard J, Hunt S, Johung KL, Kirilcuk N, Krishnamurthi S, Messersmith WA, Meyerhardt J, Miller ED, Mulcahy MF, Nurkin S, Overman MJ, Parikh A, Patel H, Pedersen K, Saltz L, Schneider C, Shibata D, Skibber JM, Sofocleous CT, Stoffel EM, Stotsky-Himelfarb E, Willett CG, Gregory KM, Gurski LA. Colon Cancer, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:329-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1054] [Cited by in RCA: 947] [Article Influence: 236.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (16)] |

| 4. | Biller LH, Schrag D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325:669-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 1417] [Article Influence: 354.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sonkin D, Thomas A, Teicher BA. Cancer treatments: Past, present, and future. Cancer Genet. 2024;286-287:18-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 173.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mutch MG. Molecular profiling and risk stratification of adenocarcinoma of the colon. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:693-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan V, Fearon DF, Merad M, Coussens LM, Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Hedrick CC, Vonderheide RH, Pittet MJ, Jain RK, Zou W, Howcroft TK, Woodhouse EC, Weinberg RA, Krummel MF. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med. 2018;24:541-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2019] [Cited by in RCA: 3795] [Article Influence: 542.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mei Y, Xiao W, Hu H, Lu G, Chen L, Sun Z, Lü M, Ma W, Jiang T, Gao Y, Li L, Chen G, Wang Z, Li H, Wu D, Zhou P, Leng Q, Jia G. Single-cell analyses reveal suppressive tumor microenvironment of human colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11:e422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hao M, Li H, Yi M, Zhu Y, Wang K, Liu Y, Liang X, Ding L. Development of an immune-related gene prognostic risk model and identification of an immune infiltration signature in the tumor microenvironment of colon cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Furuhashi M, Hotamisligil GS. Fatty acid-binding proteins: role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:489-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1415] [Cited by in RCA: 1329] [Article Influence: 78.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sun N, Zhao X. Therapeutic Implications of FABP4 in Cancer: An Emerging Target to Tackle Cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:948610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Furuhashi M. Fatty Acid-Binding Protein 4 in Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2019;26:216-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Luis G, Godfroid A, Nishiumi S, Cimino J, Blacher S, Maquoi E, Wery C, Collignon A, Longuespée R, Montero-Ruiz L, Dassoul I, Maloujahmoum N, Pottier C, Mazzucchelli G, Depauw E, Bellahcène A, Yoshida M, Noel A, Sounni NE. Tumor resistance to ferroptosis driven by Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase-1 (SCD1) in cancer cells and Fatty Acid Biding Protein-4 (FABP4) in tumor microenvironment promote tumor recurrence. Redox Biol. 2021;43:102006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Guaita-Esteruelas S, Gumà J, Masana L, Borràs J. The peritumoural adipose tissue microenvironment and cancer. The roles of fatty acid binding protein 4 and fatty acid binding protein 5. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;462:107-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wu D, Xiang L, Peng L, Gu H, Tang Y, Luo H, Liu H, Wang Y. Comprehensive analysis of the immune implication of FABP4 in colon adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0276430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sarela AI, Scott N, Ramsdale J, Markham AF, Guillou PJ. Immunohistochemical detection of the anti-apoptosis protein, survivin, predicts survival after curative resection of stage II colorectal carcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:305-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34752] [Cited by in RCA: 57122] [Article Influence: 5712.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10254] [Cited by in RCA: 16327] [Article Influence: 960.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16:284-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11591] [Cited by in RCA: 22035] [Article Influence: 1695.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Frenette PS, Wagner DD. Adhesion molecules--Part 1. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1526-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim HN, Ruan Y, Ogana H, Kim YM. Cadherins, Selectins, and Integrins in CAM-DR in Leukemia. Front Oncol. 2020;10:592733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ruan Y, Chen L, Xie D, Luo T, Xu Y, Ye T, Chen X, Feng X, Wu X. Mechanisms of Cell Adhesion Molecules in Endocrine-Related Cancers: A Concise Outlook. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:865436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu JS, Li B, Liu XS. TIMER: A Web Server for Comprehensive Analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e108-e110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2728] [Cited by in RCA: 4061] [Article Influence: 507.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martínez E, Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, Treviño V, Shen H, Laird PW, Levine DA, Carter SL, Getz G, Stemke-Hale K, Mills GB, Verhaak RG. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3056] [Cited by in RCA: 6413] [Article Influence: 583.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12:453-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4763] [Cited by in RCA: 8863] [Article Influence: 886.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Waldner M, Obenauf AC, Angell H, Fredriksen T, Lafontaine L, Berger A, Bruneval P, Fridman WH, Becker C, Pagès F, Speicher MR, Trajanoski Z, Galon J. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39:782-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1792] [Cited by in RCA: 2945] [Article Influence: 245.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hänzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7222] [Cited by in RCA: 9202] [Article Influence: 766.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Collins GS, de Groot JA, Dutton S, Omar O, Shanyinde M, Tajar A, Voysey M, Wharton R, Yu LM, Moons KG, Altman DG. External validation of multivariable prediction models: a systematic review of methodological conduct and reporting. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 532] [Cited by in RCA: 479] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Marisa L, de Reyniès A, Duval A, Selves J, Gaub MP, Vescovo L, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Schiappa R, Guenot D, Ayadi M, Kirzin S, Chazal M, Fléjou JF, Benchimol D, Berger A, Lagarde A, Pencreach E, Piard F, Elias D, Parc Y, Olschwang S, Milano G, Laurent-Puig P, Boige V. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 871] [Cited by in RCA: 1056] [Article Influence: 88.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Liu H, Weng J. A comprehensive bioinformatic analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) in glioma. Gene. 2022;822:146325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liu H, Dong A, Rasteh AM, Wang P, Weng J. Identification of the novel exhausted T cell CD8 + markers in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2024;14:19142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 66.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Liu H, Dilger JP, Lin J. A pan-cancer-bioinformatic-based literature review of TRPM7 in cancers. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;240:108302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Liu H, Weng J, Huang CL, Jackson AP. Voltage-gated sodium channels in cancers. Biomark Res. 2024;12:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nieman KM, Kenny HA, Penicka CV, Ladanyi A, Buell-Gutbrod R, Zillhardt MR, Romero IL, Carey MS, Mills GB, Hotamisligil GS, Yamada SD, Peter ME, Gwin K, Lengyel E. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat Med. 2011;17:1498-1503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1310] [Cited by in RCA: 1728] [Article Influence: 123.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Nieman KM, Romero IL, Van Houten B, Lengyel E. Adipose tissue and adipocytes support tumorigenesis and metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:1533-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 568] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Huang HW, Chang CC, Wang CS, Lin KH. Association between Inflammation and Function of Cell Adhesion Molecules Influence on Gastrointestinal Cancer Development. Cells. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lewczuk Ł, Pryczynicz A, Guzińska-Ustymowicz K. Cell adhesion molecules in endometrial cancer - A systematic review. Adv Med Sci. 2019;64:423-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bando H, Ohtsu A, Yoshino T. Therapeutic landscape and future direction of metastatic colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:306-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Pan B, Yue Y, Ding W, Sun L, Xu M, Wang S. A novel prognostic signatures based on metastasis- and immune-related gene pairs for colorectal cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1161382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hotamisligil GS, Bernlohr DA. Metabolic functions of FABPs--mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:592-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Li B, Hao J, Zeng J, Sauter ER. SnapShot: FABP Functions. Cell. 2020;182:1066-1066.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Lee CH, Lui DTW, Lam KSL. Adipocyte Fatty Acid-Binding Protein, Cardiovascular Diseases and Mortality. Front Immunol. 2021;12:589206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Xiong Y, Liu L, Xia Y, Qi Y, Chen Y, Chen L, Zhang P, Kong Y, Qu Y, Wang Z, Lin Z, Chen X, Xiang Z, Wang J, Bai Q, Zhang W, Yang Y, Guo J, Xu J. Tumor infiltrating mast cells determine oncogenic HIF-2α-conferred immune evasion in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68:731-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Chen R, Wu W, Liu T, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Zhang H, Wang Z, Dai Z, Zhou X, Luo P, Zhang J, Liu Z, Zhang LY, Cheng Q. Large-scale bulk RNA-seq analysis defines immune evasion mechanism related to mast cell in gliomas. Front Immunol. 2022;13:914001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Miao Y, Wang J, Ma X, Yang Y, Mi D. Identification prognosis-associated immune genes in colon adenocarcinoma. Biosci Rep. 2020;40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |