Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.101925

Revised: January 17, 2025

Accepted: February 5, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 175 Days and 13.3 Hours

Tissue hardness is closely related to disease pathophysiology. Shear-wave ela

To investigate SWE usefulness in measuring lymph node hardness to predict metastasis presence or absence in surgically removed lymph nodes.

This observational study obtained data from patients who underwent surgery for esophageal or gastric cancer at Nippon Medical School Hospital. The hardness of the surgically removed lymph nodes was measured using SWE. The lymph nodes with hardness values ≥ 2.2 m/s were considered clinically positive for metastasis, whereas those with lower hardness values were considered clinically negative. The lymph nodes subsequently underwent pathological examination to determine the presence of metastasis, and the SWE results and pathological assessments were compared.

A total of 1077 lymph nodes were evaluated; 18 and 15 cases of esophageal and gastric cancer were identified, respectively. The optimal cutoff value for lymph node size was calculated to be 5.1 mm, and the area under the curve value was 0.74 (95% confidence interval: 0.69-0.84). When limited to a lymph node larger than the cut off value, the SWE sensitivity and specificity for metastasis identification were 0.76 and 0.82, respectively.

SWE was useful in detecting lymph node metastases in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

Core Tip: Evaluating lymph node metastasis from malignant tumors is crucial because it significantly influences treatment planning and prognosis. Shear-wave elastography is a simple, noninvasive, and objective ultrasound method for measuring tissue stiffness. In this study, the hardness of lymph nodes removed during surgery for esophageal and gastric cancer was measured using shear-wave elastography and compared with the pathological examination. The sensitivity and specificity were 0.76 and 0.82, respectively, whereas the area under the curve was 0.74 (95% confidence interval: 0.69-0.84). Shear-wave elastography was useful in detecting lymph node metastases in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

- Citation: Suzuki M, Sakurazawa N, Hagiwara N, Kogo H, Haruna T, Ohashi R, Yoshida H. Usefulness of shear-wave elastography for detection of lymph node metastasis in esophageal and gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(4): 101925

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i4/101925.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.101925

Tissue hardness is closely associated with disease pathology; low and high hardness are more likely to indicate benign and malignant disease, respectively. Although tissue hardness is conventionally diagnosed by palpation, these assessments are subjective and difficult to perform for deep or small tissues. Consequently, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques have been developed for quantitative imaging of tissue hardness (elastography).

Shear-wave elastography (SWE), which uses ultrasound, is a simple and noninvasive technique. Multiple reports have described SWE use in areas close to the body surface such as the head and neck, skin, and breasts. For example, Liu et al[1] reported SWE is useful for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant thyroid nodules, with a sensitivity (Se) of 0.81 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.77-0.84] and specificity (Sp) of 0.84 (95%CI: 0.81-0.86). In addition, Liu et al[2] attempted to distinguish benign and malignant mass lesions of the breast with SWE and reported SWE had Se and Sp of 0.89 (95%CI: 0.86-0.91) and 0.87 (95%CI: 0.83-0.89), respectively.

In this study, we investigated the usefulness of SWE for measuring lymph node hardness and predicting the presence or absence of metastasis in surgically removed lymph nodes. For example, lymph nodes with higher hardness values are more likely positive for metastasis. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to objectively evaluate lymph node hardness by quantifying it using measurements from an ultrasound device. The secondary objective of this study was to clarify the relationship between lymph node stiffness and metastasis.

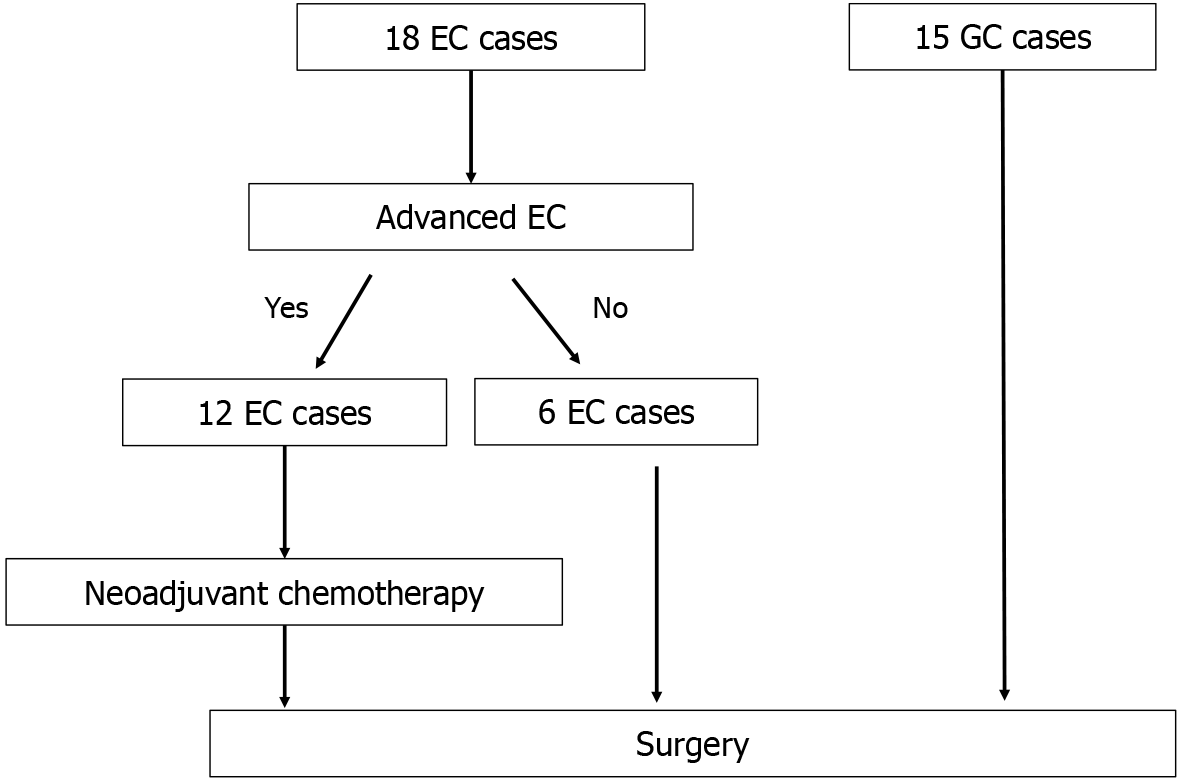

This study evaluated lymph nodes from surgical cases of esophageal cancer (EC) and gastric cancer (GC) that involved lymph node dissection at the Department of Surgery, Nippon Medical School Hospital (Sendagi, Bunkyo-ward, Tokyo, Japan) between October 1, 2022 and April 31, 2024. Patient sex and age, surgical technique, and approach method (open, laparoscopic, or robot-assisted) were not distinguished. Since neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is the standard treatment for advanced EC, the NAC group was also included for EC cases, whereas the NAC group was excluded for GC cases. Patients with benign diseases (such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors and leiomyomas) were also excluded from this study (Figure 1).

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nippon Medical School Hospital (Permit No. B-2022-582)[3]. Written consent was obtained from all the patients in this study.

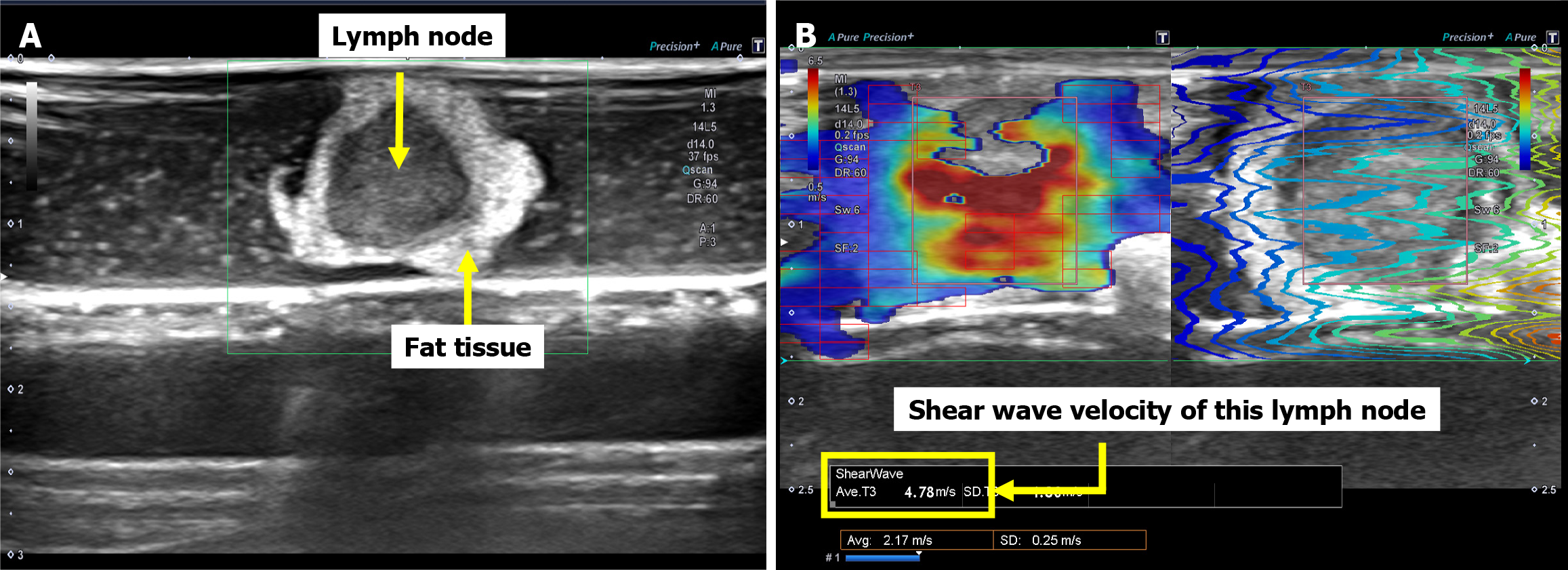

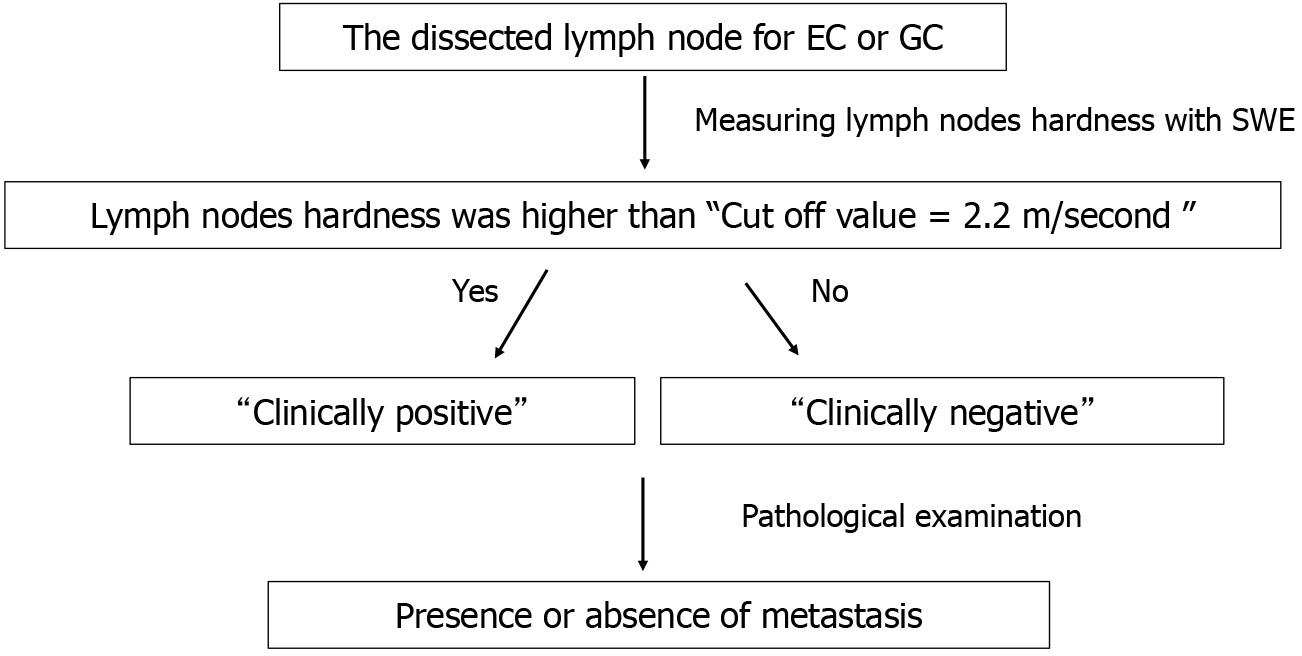

In surgeries performed for EC and GC, after specimen removal, the dissected lymph node was enucleated from the adipose tissue; placed in a petri dish soaked in 0.9% saline solution; and delineated using the B-mode of an ultrasound device for the SWE analysis (Figure 2). Lymph node measurements using SWE were performed only once on an image that accurately depicted the largest diameter of the lymph node. Since this study used surgical specimens, time was required to enucleate the lymph nodes from the adipose tissue after the specimens were removed. Therefore, SWE measurements for both EC and GC were performed 1-2 hours after specimen removal. Ten cases that were not included in the current study were analyzed in a pilot study, and the cutoff value of lymph node hardness that indicated metastasis was set at 2.2 m/s. We also referred to several previous studies on SWE for lymph nodes to confirm this cutoff value[4-6].

Two information items were collected for the main study: (1) Lymph node hardness (shear-wave velocity, m/s); and (2) Lymph node size (mm). We defined lymph node size as the largest diameter that could be delineated by the ultrasound device. In addition, lymph node measurements were performed only once on the image that depicted the largest diameter of the lymph node. Depth was adjusted according to the lymph node size. Since most lymph nodes were approximately 5 mm in size, the depth was basically set to the shallowest setting. However, for large lymph nodes greater than 1 cm, the depth was adjusted 2 to 4 steps deeper. The gain was maximized to clearly contrast the lymph nodes with the surrounding adipose tissue, thus measurements were performed with the gain maximized. Patients were diagnosed as clinically positive for metastasis if their lymph node hardness exceeded the cutoff value (2.2 m/s), and clinically negative for metastasis if the lymph node hardness was below the cutoff value. After the SWE measurements, the lymph nodes were subjected to pathological examination to evaluate the presence or absence of metastasis (Figure 3).

The SWE measurements were performed using an Aplio i800 system (Canon Medical System, Tochigi, Japan) along with a linear probe (Canon Medical System) suitable for SWE assessments. All lymph node hardness measurements using SWE were performed by a single experimenter. Therefore, there were no errors associated with different measures.

After the pathological results were obtained, the results of the SWE and pathological assessments were matched for the presence or absence of metastases. The Se, Sp, false negative (FN), false positive (FP), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated; receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated; and the area under the curve (AUC) value was determined. ROC curves were generated for lymph node size, and the optimal cutoff values were calculated.

Statistical analyses were performed using EZR (https://www.jichi.ac.jp/saitama-sct/SaitamaHP.files/statmed.html).

From October 1, 2022 and April 31, 2024, 33 surgical cases were eligible. The characteristics of the eligible patients are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. The study population included 18 EC cases and 15 GC cases.

| Characteristic | |||||

| Age: Minimum/maximum/median (years) | 50 | 84 | 71 | ||

| Sex: Men/women | 13 | 5 | |||

| Position: Ut/Mt/Lt/EGJ | 3 | 10 | 2 | 3 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy: Yes/no | 12 | 6 | |||

| Chemotherapy regimen: DCF/FP/5-FU + CDGP | 7 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Pathological histology of primary disease: Well/mod/por/tub2/other | 3 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| pT0/T1/T2/T3/T4 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| pN0/N1/N2/N3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| pStage 0 | 1 | ||||

| pStage IA/IB | 2 | 2 | |||

| pStage IIA/IIB | 2 | 3 | |||

| pStage IIIA/IIIB | 0 | 5 | |||

| pStage IVA | 3 | ||||

| Chemotherapy grade: 1a/2/3 | 7 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Characteristic | |||||

| Age: Minimum/maximum/median (years) | 32 | 89 | 72 | ||

| Sex: Men/women | 11 | 4 | |||

| Location: U/M/L | 4 | 6 | 5 | ||

| Operation: TG/DG/PG (laparoscopic operation) | 5 (1) | 10 (7) | 0 | ||

| Pathological histology of primary disease: Tub1/tub2/por1/por2/other | 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| pT1/T2/T3/T4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | |

| pN0/N1/N2/N3a/N3b | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| pStage I: A/B | 2 | 2 | |||

| pStage II: A/B | 1 | 2 | |||

| pStage III: A/B/C | 3 | 3 | 1 | ||

| pStage IV | 1 | ||||

The median age of the patients with EC was 71 (range 50-84) years. The 18 patients with EC comprised 13 men and 5 women. All the patients underwent mediastinoscopy/thoracoscopy with subtotal esophagectomy and laparoscopy-assisted gastric tube reconstruction (posterior sternal route). Of the 18 patients with EC, 12 received NAC; 7 patients received docetaxel + cisplatin + 5-fluorouracil, 2 received cisplatin + 5-fluorouracil, and 3 received 5-fluorouracil + nedaplatin. The main tumor locations were the upper thoracic esophagus in 2 patients, middle thoracic esophagus in 11 patients, lower thoracic esophagus in 2 patients, and esophagogastric junction in 3 patients. Histological assessment of the primary disease revealed 3 cases of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, 9 cases of moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, 2 cases of poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, and 2 cases of well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma. In 2 cases, only scars were detected in pathological assessments: 1 after endoscopic submucosal dissection and the other after the lesion disappeared with chemotherapy. The pathological results based on the Union for International Cancer Control classification (8th edition)[7] were: Stage 0, 1 case; Stage IA, 2 cases; Stage IB, 2 cases; Stage IIA, 2 cases; Stage IIB, 3 cases; Stage IIIB, 5 cases; Stage IVA, 3 cases. The lymph node classification was as follows: N0, 10 cases; N1, 3 cases; N2, 3 cases; and N3, 2 cases. In addition, the pathological efficacy evaluation in the NAC group indicated grade 1 in 7 cases, grade 2 in 4 cases, and grade 3 in 1 case.

Eleven patients with GC comprised 7 men and 4 women, with a median age of 78 (range 32-89) years. The surgical procedures performed were total gastrectomy in 5 patients (laparoscopic assistance, 1 patient) and distal gastrectomy in 10 patients (laparoscopic assistance, 7 patients). This study did not include patients who underwent proximal gastrectomy. The histologic types of the primary lesions were classified as follows: (1) Well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, 6 cases; (2) Moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, 2 cases; (3) Solid-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, 4 cases; (4) Non-solid-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, 2 cases; and (5) Equal amounts of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and non-solid-type poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, 1 case. Signet ring cell carcinoma was not detected in this study. The main tumor was in the upper region in 4 cases, middle region in 6 cases, and lower regions in 5 cases. The pathological results based on the Union for International Cancer Control classification (8th edition) were as follows: Stage IA, 2 cases; Stage IB, 2 cases; Stage IIA, 1 case; Stage IIB, 2 cases; Stage IIIA, 3 cases; Stage IIIB, 3 cases; Stage IIIC, 1 case; Stage IV, 1 case. One patient with stage IV disease showed postoperative peritoneal dissemination, resulting in the diagnosis of stage IV disease. The lymph node classification was as follows: N0, 5 cases; N1, 2 cases; N2, 4 cases; N3a, 2 cases; N3b, 2 cases.

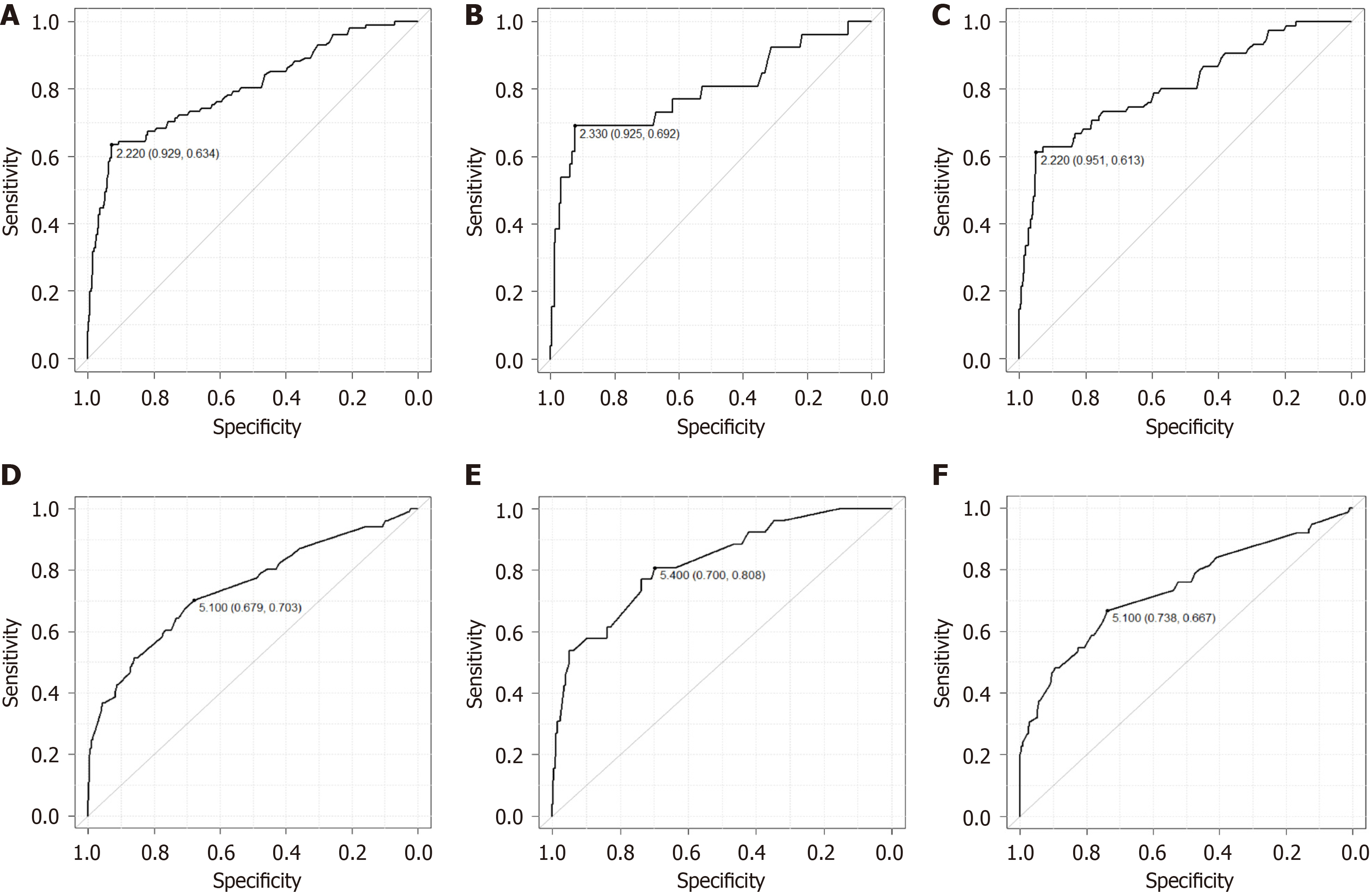

A total of 1077 lymph nodes were targeted, including 612 for EC and 465 for GC. Of the lymph nodes measured, 130 (12.1%) were diagnosed as clinically positive for metastasis with SWE > 2.2 m/s. The Se, Sp, FN, FP, PPV, and NPV of SWE are listed in Table 3. The overall Se, Sp, FN, FP, PPV, NPV were 0.63, 0.93, 0.37, 0.07, 0.46 and 0.96, respectively. The ROC curve showed an AUC of 0.80 (95%CI: 0.75-0.85). For EC, the Se, Sp, FN, FP, PPV, NPV, and AUC values were 0.69, 0.92, 0.31, 0.08, 0.28, 0.99, and 0.79 (95%CI: 0.68-0.91), respectively. The corresponding values for GC were 0.61, 0.95, 0.39, 0.05, 0.70, 0.93, and 0.81 (95%CI: 0.75-0.87), respectively (Figure 4A-C).

| Se | Sp | FN | FP | PPV | NPV | |

| All | 0.63 | 0.93 | 0.37 | 0.07 | 0.49 | 0.96 |

| EC | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.99 |

| GC | 0.61 | 0.95 | 0.39 | 0.05 | 0.7 | 0.93 |

To evaluate the effect of NAC on lymph node hardness in patients with EC, a comparison was performed between the NAC and non-NAC groups: 387 lymph nodes in 12 patients in the NAC group and 225 lymph nodes in 6 patients in the non-NAC group. A t-test determined hardness was significantly higher in the NAC group (P = 0.0455).

The size of the measured lymph nodes ranged from 2.0 mm to 42 mm (median, 5.0 mm) in EC, and the smallest node showing metastasis was 4.4 mm. For GC, the lymph nodes ranged from 2.1 to 36.1 mm (median 5.2 mm) in size, and the smallest lymph node showing metastasis was 2.8 mm. The cutoff value for the overall size of lymph nodes in EC and GC calculated using ROC curves was 5.1 mm (AUC = 0.74, 95%CI: 0.69-0.80) (Figure 4D-F). By organ, the cut off value was 5.4 mm (AUC = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.74-0.91) for EC and 5.1 mm (AUC = 0.74, 95%CI: 0.67-0.81) for GC. When the analysis was limited to lymph nodes larger than cut off value in size and SWE > 2.2 m/s, the overall Se, Sp, FN, FP, PPV, NPV were 0.76, 0.82, 0.23, 0.18, 0.53, and 0.94, respectively. The corresponding values for EC were 0.76, 0.80, 0.24, 0.20, 0.31, and 0.97, respectively; those for GC were 0.78, 0.86, 0.22, 0.14, 0.74, and 0.89, respectively (Table 4).

| Se | Sp | FN | FP | PPV | NPV | |

| All | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.94 |

| EC | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.97 |

| GC | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.74 | 0.89 |

The presence or absence of lymph node metastasis in malignant tumors greatly affects treatment strategy and prognosis. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET)-CT are widely used to examine lymph node metastasis of malignant tumors. Although metastatic lymph nodes are often enlarged on CT scans, the actual presence or absence of metastasis cannot be determined without biopsy, surgery, or pathological diagnosis. Findings that are suspicious for metastasis on contrast-enhanced CT include a short diameter of 8 mm or more, near circular shape, high degree of dark staining, and heterogeneous dark staining or necrosis[8,9]. Although the diagnostic accuracy of PET-CT is 68% for EC, the Se, Sp, and positive diagnosis rate for GC range from 17.6% to 64.5%, 85.7% to 100%, and 58% to 75.55%, respectively[10-13]. Contrast-enhanced CT and PET-CT are associated with problems such as radiation exposure, allergy to contrast agents, and high costs. In contrast, ultrasonography is a simple, non-invasive, and low cost examination. In addition, ultrasonography can allow dynamic state evaluations of the organism. Therefore, we consider it useful if ultrasonography can predict the presence of lymph node metastases.

An increasing number of reports have described the use of ultrasonography to predict the presence of metastases by measuring lymph node hardness, mainly in superficial regions of the body, and have reported good results. Suh et al[14] performed a meta-analysis of studies on metastasis identification in cervical lymph nodes using SWE and reported that the Se was 0.81 (95%CI: 72%-88%) and Sp was 0.85 (95%CI: 70%-93%). Gao et al[15] also performed a meta-analysis of SWE usefulness for the diagnosis of malignant tumors in cervical and axillary lymph nodes and reported that the Se was 0.78 (95%CI: 0.69-0.87) and Sp was 0.93 (95%CI: 0.88-0.98). However, there are few existing reports of studies evaluating lymph nodes in EC and GC by SWE due to the limiting effect of lymph node observation. In this study, we performed SWE on surgically removed specimens to solve the problem of limited observation. In the present study, we validated the lymph node hardness measured by SWE in EC and GC. The overall Se and Sp were 0.63 and 0.93, respectively, while the Se and Sp were 0.69 and 0.92 for EC and 0.61 and 0.95, respectively, for GC. When the lymph node size was limited to cut off or larger, the Se was 0.76 and Sp 0.82 overall, and 0.76 and Sp 0.80 for EC, while the Se improved to 0.78 and 0.86 for GC. The results were comparable to those of existing reports, and we believe that this study demonstrates the usefulness of SWE for evaluating lymph nodes in EC and GC. In the present study, a statistically significant difference was observed between the NAC and non-NAC groups in EC (P = 0.045). We consider the following possibilities; advanced EC patients who are eligible for NAC are more likely to have developed lymph node metastases than those in the non-NAC group. Therefore, the NAC group contained more lymph nodes with higher firmness than the non-NAC group, but after NAC, the lymph node metastases disappeared and only fibrosis remained. As a result, no metastases remained in the surgically removed lymph nodes, which were judged pathologically negative for metastasis, but the fibrosis remained high in firmness, which might have contributed to the significant difference. As for fibrosis in the lymph nodes, Takahashi et al[16] reported that histological observation of fibrosis or necrosis in the resected lymph nodes after chemoradiotherapy indicated the presence of lymph node metastasis before chemoradiotherapy. In the present results, PPV was relatively good at 0.70 for GC, while it decreased to 0.28 for EC. Although a clear mechanism cannot be determined, we speculated that the NAC affected the results. As mentioned above, advanced EC patients undergoing NAC often had lymph nodes with metastatic disease and high stiffness. These lymph nodes were judged pathologically negative because NAC eliminated metastases, but fibrosis remained, and stiffness was measured to be high. The high number of these false-positive lymph nodes may have affected the PPV results when compared to GC.

In EC and GC, measurement of lymph node hardness from the body surface using ultrasonography may help predict the presence or absence of metastasis. However, in many cases, ultrasound evaluations of lymph nodes related to EC and GC are difficult because of patient physique and the presence of air in the digestive tract. For example, evaluation of deeply located lymph nodes, such as those in the mediastinum in EC, and those in the pancreatic tail around the splenic artery in GC, is particularly difficult. In addition, small lymph nodes are difficult to delineate with ultrasonography from the body surface alone; thus, all lymph nodes cannot be evaluated using ultrasound equipment alone. Particularly in GC, lymph nodes < 2 mm may metastasize and should be treated with caution[17]. In this study, we resolved these limitations of observation by performing ultrasound observations on surgically removed specimens. In the excised specimens, lymph nodes as small as 2 mm could be measured without any problem. However, future improvements in the accuracy of ultrasound equipment will allow imaging of specimens using ultrasonography.

As mentioned previously, ultrasound examination has the advantage of being simple, non-invasive, and low cost. In addition, SWE is an objective examination and prompt results. Therefore, we expected the following utilization for intraoperative SWE and measurement of lymph node hardness: (1) Applications for reduction surgery; and (2) Evaluate enlarged lymph nodes that are difficult to dissect. Recent improvements in examination techniques, especially endoscopy, have allowed the detection and diagnosis of early-stage cancers that do not require lymph node dissection. In addition, the aging population will result in an increase in the number of patients who are intolerant to surgery, and the need for reduced surgery, which involves a reduced extent of lymph node dissection, is expected to increase. For breast cancer and malignant melanoma, sentinel node (SN) biopsy, a reduction technique based on nuclear medicine and dye-based methods, has been established. The residual income method using 99mTc is often used to identify SN in EC, and its results are generally good, with an identification rate of 88%-95% and a positive diagnosis rate of 91%-94%[18,19]. However, the indications should be carefully evaluated in cases of advanced cancer with tumor stage cT3 or higher, cases with clear positive lymph nodes, and cases in which preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy has been administered because destruction or alteration of lymphatic flow cannot be ruled out in such cases[20]. The concept of SN biopsy has also been proposed for early-stage GC. Niihara et al[21] studied 385 cases of cT1N0 and cT2N0 GC and reported that the concept of an SN is valid for GC if the tumor is cT1N0 and less than 4 cm in length. However, the accuracy of preoperative diagnosis for the extent and lymph node metastasis in GC is insufficient, and the safety and usefulness of SN biopsy for GC needs to be fully examined in the future. In addition, although intraoperative rapid diagnosis is used to evaluate SNs, its accuracy for the diagnosis of micro-metastasis is not sufficient because these evaluations are generally performed using any fragments. In this study, SWE predicted lymph node metastasis with a certain degree of accuracy regarding both Se and Sp, and SWE for SNs can be used as an adjunctive test for rapid intraoperative diagnosis, which may be useful when performing radical reduction surgery without compromising the curative effect of the procedure.

The observation of lymph nodes from the body surface with ultrasound equipment is affected by patient physique, air in the luminal organs, and varies from organ to organ. Lymph nodes close to the body surface can be adequately evaluated with ultrasound equipment from the body surface. Examples include cervical lymph nodes in EC and inguinal lymph nodes in rectal cancer. In contrast, lymph nodes in the mediastinum in EC are strongly influenced by the lungs, heart, and rib cage, making detailed evaluation from the body surface difficult in many cases. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can be useful for evaluating lymph nodes in the mediastinum, and Sazuka et al[22] reported good SWE results using EUS for lymph nodes in EC. In EC, the abdominal lymph nodes, and in GC, the lymph nodes around the gastric kyphosis and kyphoscoliosis, the celiac artery, and its branches, the common hepatic artery and splenic artery, are important, and they can be observed to some extent with ultrasound equipment from the body surface. However, since even smaller lymph nodes are more likely to be positive for metastasis in GC, this limits observation using ultrasound equipment from the body surface. In colon cancer, lymph nodes around the superior mesenteric artery and inferior mesenteric artery are important. The small intestine is extensively located ventral to the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries, and observation of lymph nodes in this region is often difficult because they are more affected by air in the lumen of the small intestine. Similarly, para-rectal lymph nodes in rectal cancer are difficult to observe, and as with lymph nodes in the thoracic cavity and mediastinum in EC, measurement using EUS is considered. We believe that by devising a method for each organ of interest, a simple, noninvasive, and highly accurate examination can be performed.

This study has a few limitations: (1) It was conducted using surgical specimens. Thus, blood and lymphatic flow were blocked, and measurements were made under conditions different from those in vivo; (2) The thermal damage caused by surgical manipulation, contusion, and fragmentation of the lymph nodes during specimen preparation may have influenced the results; and (3) Lymph nodes vary in shape, although most are spherical, they may be flattened or arranged in a dharma-like pattern in some cases. These changes may preclude correct measurements of hardness depending on the cross-sectional area depicted by ultrasound. Thus, awareness of the shape of the lymph nodes and scanning them systematically are important for accurate measurements of hardness.

In this study, SWE was performed on lymph nodes, which enabled the prediction of lymph node metastasis with high accuracy in upper gastrointestinal tract. In the future, we intend to expand the indication to other gastrointestinal cancers, such as colorectal and rectal cancer. Furthermore, although this study was conducted as a standalone test, further improvements in accuracy can be expected by combining SWE with other tests. In the future, we also plan to improve the accuracy of this technique by combining it with other techniques such as PET-CT, indocyanine green tests, and MRI-elastography. We believe that this study could serve as a basis for future research as mentioned above.

This study demonstrated that SWE may be useful for detection of lymph node metastases with high accuracy in upper gastrointestinal tract.

Cannon Medical provided technical information for the ultrasound equipment and SWE. The Department of Diagnostic Pathology at Nippon Medical School Hospital assisted with specimen preparation and pathological diagnosis.

| 1. | Liu BJ, Li DD, Xu HX, Guo LH, Zhang YF, Xu JM, Liu C, Liu LN, Li XL, Xu XH, Qu S, Xing M. Quantitative Shear Wave Velocity Measurement on Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Elastography for Differential Diagnosis between Benign and Malignant Thyroid Nodules: A Meta-analysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41:3035-3043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu B, Zheng Y, Huang G, Lin M, Shan Q, Lu Y, Tian W, Xie X. Breast Lesions: Quantitative Diagnosis Using Ultrasound Shear Wave Elastography-A Systematic Review and Meta--Analysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:835-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Otsuka T, Matsuyama K. Nippon Medical School's Ethical Review Processes for Studies Involving Human Subjects. J Nippon Med Sch. 2024;91:136-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen BB, Li J, Guan Y, Xiao WW, Zhao C, Lu TX, Han F. The value of shear wave elastography in predicting for undiagnosed small cervical lymph node metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A preliminary study. Eur J Radiol. 2018;103:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cheng KL, Choi YJ, Shim WH, Lee JH, Baek JH. Virtual Touch Tissue Imaging Quantification Shear Wave Elastography: Prospective Assessment of Cervical Lymph Nodes. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:378-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Togawa R, Binder LL, Feisst M, Barr RG, Fastner S, Gomez C, Hennigs A, Nees J, Pfob A, Schäfgen B, Stieber A, Riedel F, Heil J, Golatta M. Shear wave elastography as a supplemental tool in the assessment of unsuspicious axillary lymph nodes in patients undergoing breast ultrasound examination. Br J Radiol. 2022;95:20220372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Onbaş O, Eroglu A, Kantarci M, Polat P, Alper F, Karaoglanoglu N, Okur A. Preoperative staging of esophageal carcinoma with multidetector CT and virtual endoscopy. Eur J Radiol. 2006;57:90-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mazzeo S, Caramella D, Gennai A, Giusti P, Neri E, Melai L, Cappelli C, Bertini R, Capria A, Rossi M, Bartolozzi C. Multidetector CT and virtual endoscopy in the evaluation of the esophagus. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:2-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ba-Ssalamah A, Prokop M, Uffmann M, Pokieser P, Teleky B, Lechner G. Dedicated multidetector CT of the stomach: spectrum of diseases. Radiographics. 2003;23:625-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yun M, Lim JS, Noh SH, Hyung WJ, Cheong JH, Bong JK, Cho A, Lee JD. Lymph node staging of gastric cancer using (18)F-FDG PET: a comparison study with CT. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1582-1588. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lehmann K, Eshmuminov D, Bauerfeind P, Gubler C, Veit-Haibach P, Weber A, Abdul-Rahman H, Fischer M, Reiner C, Schneider PM. (18)FDG-PET-CT improves specificity of preoperative lymph-node staging in patients with intestinal but not diffuse-type esophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:196-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Han D, Yu J, Zhong X, Fu Z, Mu D, Zhang B, Xu G, Yang W, Zhao S. Comparison of the diagnostic value of 3-deoxy-3-18F-fluorothymidine and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the assessment of regional lymph node in thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a pilot study. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:416-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu Q, Li J, Xin B, Sun Y, Feng D, Fulham MJ, Wang X, Song S. (18)F-FDG PET/CT Radiomics for Preoperative Prediction of Lymph Node Metastases and Nodal Staging in Gastric Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:723345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Suh CH, Choi YJ, Baek JH, Lee JH. The diagnostic performance of shear wave elastography for malignant cervical lymph nodes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:222-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gao Y, Zhao Y, Choi S, Chaurasia A, Ding H, Haroon A, Wan S, Adeleke S. Evaluating Different Quantitative Shear Wave Parameters of Ultrasound Elastography in the Diagnosis of Lymph Node Malignancies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Takahashi Y, Soh J, Shien K, Yamamoto H, Yamane M, Kiura K, Kanazawa S, Yanai H, Toyooka S. Fibrosis or Necrosis in Resected Lymph Node Indicate Metastasis Before Chemoradiotherapy in Lung Cancer Patients. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:4419-4423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Noda N, Sasako M, Yamaguchi N, Nakanishi Y. Ignoring small lymph nodes can be a major cause of staging error in gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:831-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Takeuchi H, Fujii H, Ando N, Ozawa S, Saikawa Y, Suda K, Oyama T, Mukai M, Nakahara T, Kubo A, Kitajima M, Kitagawa Y. Validation study of radio-guided sentinel lymph node navigation in esophageal cancer. Ann Surg. 2009;249:757-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Uenosono Y, Arigami T, Yanagita S, Kozono T, Arima H, Hirata M, Kita Y, Uchikado Y, Okumura H, Matsumoto M, Natsugoe S. Sentinel node navigation surgery is acceptable for clinical T1 and N0 esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2003-2009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Takeuchi H, Kitagawa Y. [Preoperative diagnosis of lymph node metastases and sentinel node navigation surgery in patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer]. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2008;109:90-94. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Niihara M, Takeuchi H, Nakahara T, Saikawa Y, Takahashi T, Wada N, Mukai M, Kitagawa Y. Sentinel lymph node mapping for 385 gastric cancer patients. J Surg Res. 2016;200:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sazuka T, Akai T, Uesato M, Horibe D, Kuboshima M, Kitabayashi H, Matsunaga A, Kagaya A, Muto Y, Takeshita N, Maruyama T, Miyazawa Y, Shuto K, Shiratori T, Kono T, Akutsu Y, Hoshino I, Matsubara H. Assessment for diagnosis of lymph node metastasis in esophageal cancer using endoscopic ultrasound elastography. Esophagus. 2016;13:254-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |