Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.100089

Revised: December 5, 2024

Accepted: February 5, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 230 Days and 4.7 Hours

Pancreatic fistula is the most common complication of pancreatic surgeries that causes more serious conditions, including bleeding due to visceral vessel erosion and peritonitis.

To develop a machine learning (ML) model for postoperative pancreatic fistula and identify significant risk factors of the complication.

A single-center retrospective clinical study was conducted which included 150 patients, who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy. Logistic regression, random forest, and CatBoost were employed for modeling the biochemical leak (symptomless fistula) and fistula grade B/C (clinically significant complication). The performance was estimated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under the curve (AUC) after 5-fold cross-validation (20% testing and 80% training data). The risk factors were evaluated with the most accurate algorithm, based on the parameter “Importance” (Im), and Kendall correlation, P < 0.05.

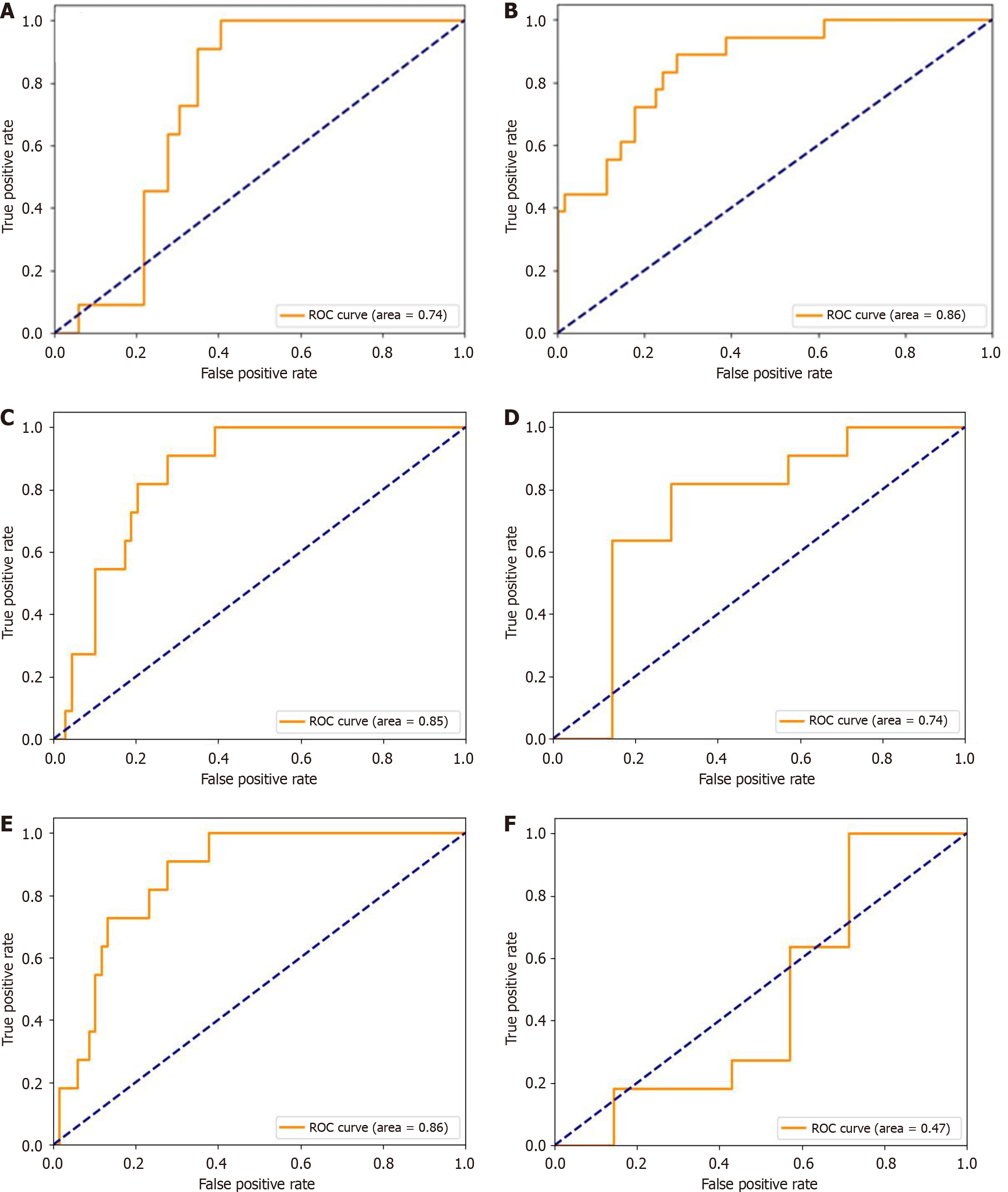

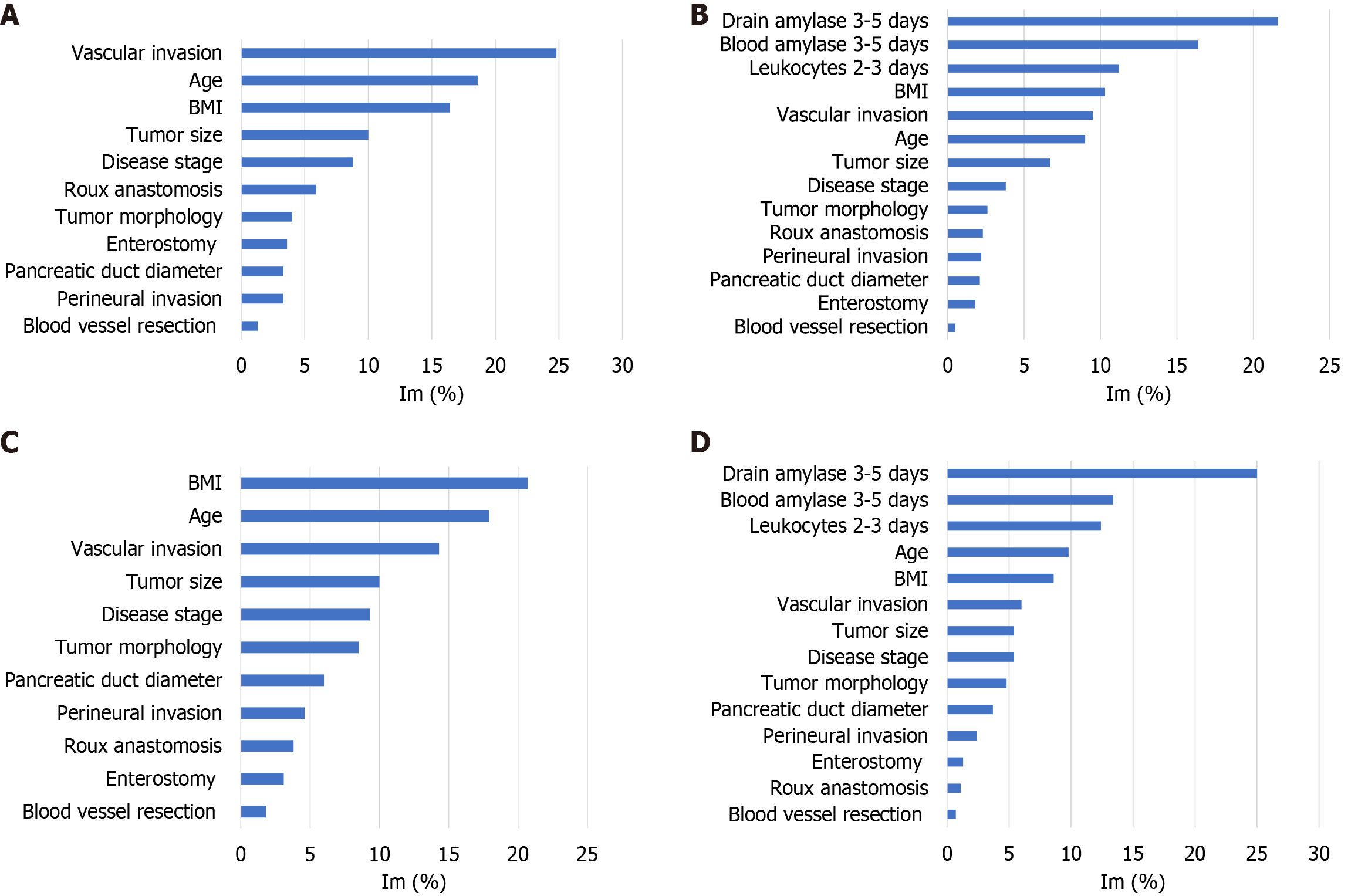

The CatBoost algorithm was the most accurate with an AUC of 74%-86%. The study provided results of ML-based modeling and algorithm selection for pancreatic fistula prediction and risk factor evaluation. From 14 parameters we selected the main pre- and intraoperative prognostic factors of all the fistulas: Tumor vascular invasion (Im = 24.8%), age (Im = 18.6%), and body mass index (Im = 16.4%), AUC = 74%. The ML model showed that biochemical leak, blood and drain amylase level (Im = 21.6% and 16.4%), and blood leukocytes (Im = 11.2%) were crucial predictors for subsequent fistula B/C, AUC = 86%. Surgical techniques, morphology, and pancreatic duct diameter less than 3 mm were insignificant (Im < 5% and no correlations detected). The results were confirmed by correlation analysis.

This study highlights the key predictors of postoperative pancreatic fistula and establishes a robust ML-based model for individualized risk prediction. These findings contribute to the advancement of personalized perioperative care and may guide targeted preventive strategies.

Core Tip: The study provides a machine-learning approach with a focus on medical data evaluation, based on algorithm selection. The best algorithm was CatBoost. Young age and large tumor size were associated with fistula B/C and biochemical leak development. Blood and drain amylase level increases and biochemical leak were the major risk factors of subsequent fistula B/C development.

- Citation: Potievskiy MB, Petrov LO, Ivanov SA, Sokolov PV, Trifanov VS, Grishin NA, Moshurov RI, Shegai PV, Kaprin AD. Machine learning for modeling and identifying risk factors of pancreatic fistula. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(4): 100089

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i4/100089.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.100089

According to World Health Organization statistics, pancreatic cancer is associated with poor prognosis and is considered one of the most common causes of mortality in oncological patients[1,2]. The main step in pancreatic cancer treatment is surgery: Pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) and distal pancreatic resection. Pancreatic surgery requires high-level techniques, and is associated with a high risk of complications. Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is the most common com

The main fistula criterion is an increase of more than 3-fold in pancreatic amylase level in drain fluid, compared to the normal blood level. The International Group of Studying Pancreatic Fistula (IGSPF) classified pancreatic fistula into 3 grades: Biochemical leak (grade A fistula before 2016), grade B and C fistulas[8,9]. Biochemical leak is an isolated increase in pancreatic amylase drain level, considered clinically insignificant. Fistulas B and C are characterized by clinical symptoms with different severity. Fistulas are usually diagnosed within the first 5 days after surgery; however, fistulas that develop up to 30 days after surgery are also common[5,6,9-11].

The IGSPF identified other intraoperative risk factors: Soft pancreatic texture, severe hemorrhage, long duration of surgery, and tumor morphology. The criteria were included in the fistula risk score calculator[5,12-14]. There were several attempts to develop a wider scale for pancreatic fistula risk, but the quality of results was insufficient[7,15]. Other potential risk factors may be evaluated before and after surgery and include clinical, demographic parameters, and surgical techniques. Possible risk factors are high body mass index (BMI), age, and male sex, comorbidities, and surgical techniques[6,16,17]; however, their significance is controversial. Pancreatic duct diameter is an important predictor of POPF; however, different studies consider high or low values a risk factor[16,17]. In addition, Villodre et al[18] in 2023 suggested tumor vascular invasion as a risk factor of pancreatic fistula.

High drain amylase level should be considered not only the diagnostic criterion for biochemical leak but also one of the main postoperative risk factors for subsequent pancreatic fistula B/C[12,19,20]. Nevertheless, the significance of the early increase in drain amylase level (within 5 days after PD) was validated in association with other possible risk factors, applying the evidence-based approach[21,22].

We believe that the implementation of a personal approach in pancreatic cancer surgery will help to predict pancreatic fistula and correct the treatment strategy[23,24]. Machine learning (ML) as a group of artificial intelligence (AI) methods is successfully implemented in various branches of industry and science[25]. Applied to clinical data, ML technologies provide the ability to create prognostic models of complication development and allow physicians to personalize treatment and diagnostic strategies[26]. Such models are usually used for individual prognosis[27-30]. There have been several attempts at AI-based POPF modeling. Lee et al[31] developed a deep learning based model of fistula after PD that included computed tomography and clinical data. Other studies presented a ML model based on preoperative data[32,33] and a drain-removal prediction model[34]. The latter included in the analysis, only classification ML algorithms without logistic regression. Selection of an optimal algorithm from various types will help to develop the best model[34]. We believe that by presenting the ML-based solution to a crucial problem in surgery, we will translate the effectiveness of the approach for precision medicine[30].

This study aimed to develop a predictive ML model for POPF and identify the main risk factors of the complication. By incorporating a comprehensive dataset including preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative parameters, we sought to develop an accessible and accurate risk prediction tool for clinical practice.

We performed a single-center retrospective clinical study, which included 150 patients who underwent PD in FSBI NMRRC from 2018 to 2023. The inclusion criteria were age 18-75 years, verified diagnosis of neoplasm in the pancreaticoduodenal region, PD, and stage of the disease: Early, locally advanced, and marginally resectable. The non-inclusion/exclusion criteria were: Severe comorbidity, age less than 18 and more than 75 years, performance status Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 2 or more before surgery, metastases, and inability to perform radical operation. All the patients, meeting the inclusion criteria without non-inclusion/exclusion criteria were included in the study. We performed initial diagnosis and treatment in association with NCCN guidelines[35]. The patient list was obtained from the clinic database. All the data, including results of postoperative laboratory tests, were collected from medical records, according to the guidelines for retrospective studies[11].

All the patients underwent surgery via the standard surgical protocol of PD. This protocol involves the en bloc resection of the pancreatic head, duodenum, proximal jejunum, common bile duct, and gallbladder. The resection is followed by meticulous reconstruction to restore gastrointestinal continuity. The protocol included standard lymphadenectomy and vascular resection and reconstruction in case of vascular involvement. Patient data were collected from electronic medical records and included demographic characteristics, comorbidities, intraoperative parameters, and postoperative outcomes.

The patients were divided into 3 groups: “no fistula”, “biochemical leak”, and “fistula B/C”. Pancreatic fistula was diagnosed using IGSPF criteria[9]. Patients, included in the "fistula B/C” group had increased drain amylase levels 3 times greater than normal blood levels with clinical symptoms of fistula B/C. Biochemical leak was defined as an increased drain amylase level without clinical symptoms. Patients with “no fistula” had drain amylase levels no more than 3 times the normal blood level without clinical symptoms of pancreatic fistula. Due to the considered clinical insignificance of biochemical leak, we studied joined groups: “Fistula B/C and biochemical leak” and “no fistula and biochemical leak”. The fraction of patients with biochemical leak was 12.3% and with fistula B/C was 14.2%.

ML mathematical modeling includes several steps: Model feature selection, model training, quality check, algorithm selection, and risk factor evaluation. We developed two types of models: Binary and 3-dimensional. The binary model included two classes: Patients with no fistula and patients with biochemical leak or fistula B/C. The 3-dimensional model included 3 classes: No fistula, biochemical leak, and fistula B/C. The models were developed with the pre- and intraoperative data and with additional clinical information, collected 3-5 days after the surgery.

In the first step, we selected features for ML modeling. To develop an accurate ML model, suitable for implementation in clinical practice, evaluation of clinical parameters is required. We selected 25 potential risk factors, based on the latest scientific data and available medical records[3,5,12]. Next, from 25 clinical parameters we selected 14 features for optimal model development (Table 1) with simulated annealing, which is a randomized algorithm of suboptimal optimization. The algorithms make small random changes in a subset of features, optimizing the function of POPF. According to the latest research, this step is crucial for high-quality ML model development[29,36-38].

| Groups parameters | All patients | No fistula | No fistula and biochemical leak | Fistula B/C and biochemical leak | Biochemical leak | Fistula B/C |

| Qualitative disease and treatment parameters (%) | ||||||

| Blood vessel resection | 15.3 | 19.8 | 16.8 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 0 |

| Perineural invasion | 46.9 | 55.6 | 52.6 | 23.3 | 14.3 | 31.3 |

| Vascular invasion | 48.7 | 59.3 | 54.7 | 20 | 14.3 | 25 |

| Enterostomy | 23.1 | 76.2 | 24.7 | 25 | 50 | 14.3 |

| Roux anastomosis | 36.3 | 87.9 | 37.7 | 20 | 0 | 28.6 |

| Tumor morphology (%) | ||||||

| Benign tumor | 2.02 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 4 | 10 | 0 |

| Neuroendocrine cancer | 10.1 | 6.8 | 9.5 | 20 | 30 | 13.3 |

| Epithelial malignant tumor | 87.9 | 91.9 | 88.1 | 76 | 60 | 86.7 |

| Disease stage (%) | ||||||

| I | 17 | 16.9 | 16.5 | 17.2 | 14.3 | 20 |

| IIa | 24 | 22.5 | 22.4 | 27.6 | 21.4 | 33.3 |

| IIb | 30 | 29.6 | 30.6 | 31 | 35.7 | 26.7 |

| III | 20 | 21.1 | 21.2 | 17.2 | 21.4 | 13.3 |

| IV | 9 | 9.9 | 9.4 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 6.7 |

| Quantitative parameters, median (interquartile range) | ||||||

| Age | 61 (53.75, 66) | 62 (54.75, 68) | 60.5 (54, 66) | 56.5 (46, 62.75) | 61 (50.75, 64.75) | 54.5 (46, 59.5) |

| Blood amylase 3-5 days, mM | 50 (29.5, 91.7) | 44 (24, 70) | 51 (30, 91.6) | 81 (37, 138) | 45.5 (32.5, 97.15) | 91.8 (66.5, 246) |

| Drain amylase 3-5 days, mM | 81 (17.75, 1243) | 23 (13.5, 44.5) | 81 (19.25, 1341) | 2445 (628.2; 3725) | 932.5 (370.25, 1653.75) | 4065 (3707, 5000) |

| Leukocytes 2-3 days, 109/L | 13.1(9.25, 17.45) | 12.4 (9.225, 15.7) | 12.8 (9.3, 17.2) | 16.7 (11.85, 20.35) | 16.7 (11.7, 20.8) | 14.85 (12.1, 19.025) |

| Tumor size, mm3 | 12.5 (5.1, 32) | 5 (3, 7.25) | 12.5 (5.25, 36.26) | 3 (2.5, 4.375) | 3 (2.5, 3.75) | 3 (2.95, 4.5) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.26 (23.1, 28.21) | 25.3 (23, 28.1) | 25.3 (23, 28.1) | 25.8 (23, 28.1) | 24.5 (21.6, 27.5) | 25.9 (23.9, 28.2) |

| Pancreatic duct diameter, mm | 4.5 (2.5, 7) | 5 (3, 7.25) | 4.5 (2.5, 7) | 3 (2.5, 4.36) | 3 (2.5, 3.75) | 3 (2.95, 4.5) |

The parameters included were demographic and clinical characteristics (age, BMI, and disease stage I-IV), operative approaches (applied Roux anastomosis, enterostomy, blood vessel resection), instrumental values (tumor volume, vascular, perineural invasion, and diameter of pancreatic duct), and tumor type (benign, neuroendocrinal, and epithelial malignancies). Laboratory values included were blood and drain amylase levels, measured 3-5 days after surgery, and blood leukocyte level at 2-3 days. Tumor morphology and vascular and perineural invasion were initially studied before surgery with biopsy and the morphological diagnosis was confirmed after the operation. Qualitative parameters were transformed into numerical equivalents. We classified the tumor morphological types by clinical prognosis: Benign: 0, neuroendocrinal malignancies: 1, and epithelial malignancies: 2. We studied pancreatic fistula as the primary outcome of PD which was selected as the target variable for all the models.

We developed logistic regression, random forest, and CatBoost algorithms to select the most accurate one. Logistic regression is a linear algorithm that is effective for modeling qualitative parameters. Random forest and CatBoost are non-linear ML algorithms, based on decision trees[38,39] and the latter includes ordered gradient boosting. CatBoost is considered unbiased and effective in classification models with categorical variables[40-42]. Thus, we selected one linear and two non-linear algorithms to select the most accurate one suitable to the dataset.

To prevent overtraining, we performed a 5-fold cross-validation[43]. We tested the model quality with metric receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under the curve (AUC)[43,44]. ROC is a function between specificity and 1-sensitivity and ROC AUC is an integral of the parameters. To improve the model qualities we searched for the best hyperparameters with the GridSearch algorithm[45]. Hyperparameter tuning is a procedure of search for the optimal configurable parameters of the ML model. The most accurate algorithm was selected for risk factor evaluation.

The code was developed in Jupyter Notebook, Anaconda 3, Python 3.7. We developed the algorithms and selected hyperparameters with the sklearn library. Cross-validation was performed with sklearn.model_selection.StratifiedKFold, and hyperparameters were selected with sklearn.model_selection.GridSearchCV[45].

The risk factors were evaluated with standard approaches available in the sklearn library. Logistic regression evaluates risk factors by the coefficients and their significance. In the case of the decision tree algorithm, the parameter “Importance” (Im) is estimated, which is a relative value of Gini impurity change, corrected on standard deviation. Gini impurity measures how often a randomly chosen element of a set would be incorrectly labeled if it were labeled randomly and independently according to the distribution of labels in the set[39].

To evaluate possible risk factors, associated with POPF, we combined ML modeling with Kendall correlation analysis, P < 0.05. In cases of multiplicity, we employed family-wise error rate Bonferroni correction to adjust P values and prevent correlations from incorrectly appearing to be statistically significant[46]. The statistical analysis was performed in Statistica 13.2 and RStudio with the programming language R.

We detected a significant positive correlation between blood and drain amylase level increase and subsequent development of biochemical leak and pancreatic fistula B/C (r = 0.25, P = 0.017 and r = 0.74, P = 8.37 × 10-9), including joint groups: “Fistula B/C and biochemical leak” (r = 0.24, P = 0.02 and r = 0.77, P = 1.56 × 10-7) and “no fistula and biochemical leak” (r = 0.24, P = 0.02 and r = 0.77, P = 1.56 × 10-7). The same results were received for young age (r = -0.23,

| Correlated groups parameters | No fistula-0; biochemical leak-1; fistula-2 | No fistula and biochemical leak- 0; fistula B/C-1 | No fistula-0; biochemical leak and fistula B/C-1 | |||

| r value | P value | r value | P value | r value | P value | |

| Age | -0.23 | 0.021a | -0.24 | 0.014b | -0.21 | 0.031a |

| Enterostomy | -0.05 | 0.637 | -0.06 | 0.536 | -0.04 | 0.676 |

| Roux anastomosis | -0.2 | 0.064 | -0.09 | 0.409 | -0.22 | 0.04 |

| Blood vessel resection | -0.13 | 0.226 | -0.2 | 0.071 | -0.12 | 0.288 |

| Disease stage | -0.12 | 0.251 | -0.11 | 0.3 | -0.12 | 0.259 |

| Blood amylase 3-5 days | 0.25 | 0.017b | 0.24 | 0.024a | 0.24 | 0.02a |

| Drain amylase 3-5 days | 0.74 | 8.37 × 10-9b | 0.51 | 0.0004b | 0.7 | 1.56 × 107b |

| Leukocytes 2-3 days | 0.16 | 0.121 | 0.09 | 0.371 | 0.17 | 0.1 |

| Tumor morphology | 0.16 | 0.127 | 0.12 | 0.222 | 0.16 | 0.117 |

| Tumor size, mm3 | -0.01 | 0.934 | -0.06 | 0.571 | 0.004b | 0.975 |

| Perineural invasion | -0.31 | 0.002b | -0.18 | 0.062 | -0.33 | 0.001b |

| Vascular invasion | -0.32 | 0.001b | -0.17 | 0.088 | -0.35 | 0.0003b |

| BMI | -0.04 | 0.239 | 0.001 | 0.672 | -0.04 | 0.382 |

| Pancreatic duct diameter | -0.08 | 0.437 | 0.03 | 0.743 | -0.11 | 0.293 |

According to the IGSPF, fistula B/C is a clinically significant complication in contrast to biochemical leak[8]. However, biochemical leak may increase the risk of fistula B/C development[12]. Therefore, at the first step of the study, we developed binary ML models (logistic regression, random forest, and CatBoost) that distinguish patients with no fistula from patients with fistula B/C or biochemical leak. We developed ML models, based on pre- and intraoperative data, and additional data, collected 3-5 days after surgery. After cross-validation and hyperparameters selection, CatBoost was detected as the most accurate algorithm, with the best ROC AUC (Table 3).

| Algorithm model | Logistic regression | Random forest | CatBoost |

| 5-fold cross validation ROC AUC1 | |||

| Pre- and intraoperative data model | 0.71 ± 0.11 | 0.77 ± 0.08 | 0.74 ± 0.1 |

| 3-5 days after surgery | 0.86 ± 0.09 | 0.8 ± 0.11 | 0.87 ± 0.07 |

| 5-fold cross validation ROC AUC2 | |||

| Pre- and intraoperative data model | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| 3-5 days after surgery | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.86 |

We developed a three-dimensional model, distinguishing no fistula, fistula B/C, and biochemical leak. The model was employed in two ways: To predict fistula B/C in general, considering biochemical leak as no fistula (fistula B/C vs other classes) and to predict fistula B/C in patients with an increased amylase drain level according to the IGSPF criteria (fistula B/C vs biochemical leak). The quality of each prediction was evaluated separately (Table 4).

| Algorithm model | Logistic regression | Random forest | CatBoost |

| 5-fold cross validation ROC AUC1 | |||

| Pre- and intraoperative data model | 0.71 ± 0.088 | 0.67 ± 0.09 | 0.68 ± 0.07 |

| 3-5 days after surgery | 0.77 ± 0.145 | 0.726 ± 0.145 | 0.74 ± 0.16 |

| 5-fold cross validation ROC AUC2 | |||

| Pre- and intraoperative data model: Fistula B/C vs other classes | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.85 |

| 3-5 days after surgery: Fistula B/C vs other classes | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.86 |

| Pre- and intraoperative data model: Fistula B/C vs biochemical leak | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.74 |

| 3-5 days after surgery: Fistula B/C vs biochemical leak | 0.39 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

In the case of the three-dimensional model, CatBoost was also the most accurate algorithm with the best ROC AUC. We suggest that the result is associated with the inclusion of qualitative parameters with different classes as boosting algorithms are good for such data analysis[30,42,47].

All the models had good quality, but the lowest ROC AUC was detected for logistic regression which may indicate non-linear data. Random forest and CatBoost are quite similar algorithms, based on decision trees; therefore it is enough to employ the best one in accordance with the ROC AUC, for risk factor evaluation. Thus, we selected the CatBoost algorithm for risk factor evaluation, based on the quality of binary and three-dimensional algorithms (Table 3 and Table 4). All further predictions and risk factor analysis were based on CatBoost ML models. To measure the importance of potential risk factors, we calculated the relative parameter Im[42].

There are various ways to select the main predictors from an ML model. Our study aimed to scale the possible risk factors, and at the same time select the main risk factors considering the highest difference between Ims as the border, and employing cut-offs of Im (5%)[48-51].

According to the binary CatBoost model, developed using pre- and intraoperative data, ROC AUC = 74% (Table 3 and Figure 1A), the main risk factors of fistula B/C and biochemical leak were tumor vascular invasion, age, and BMI, Im = 24.8, 18.6, and 16.4, respectively (Figure 2A). Risk factors with lower significance were tumor size, disease stage, and Roux anastomosis Im = 10, 8.8, and 5.9, respectively. Tumor morphology, enterostomy, pancreatic duct diameter, perineural invasion, and blood vessel resection Ims were below 5%.

The binary model, based on the data known at 3-5 days after surgery, ROC AUC = 86% (Table 3 and Figure 1B), detected the main risk factors: Drain and amylase levels on 3-5 days after surgery, blood leukocytes, measured at 2-3 days, Im = 21.6%, 16.4%, and 11.2%, respectively. According to the IGSPF, the main diagnostic criterion of pancreatic fistula is an increase in the amylase drain level more than 3 times that in the blood; therefore, the results support the validity of the model. BMI, tumor vascular invasion, and age were also important risk factors, Im = 10.3%, 9.5%, and 9%, respectively. The Im of tumor size was 6.7%, and the Ims of the remaining parameters were less than 5% (Figure 2B).

The same results were obtained from the correlation analysis. Tumor vascular invasion was more common in patients with no fistula in comparison to patients with biochemical leak, fistula B/C, and the joint group “biochemical leak and fistula B/C” (Table 1). Patients with fistula B/C and patients in the joint group “biochemical leak and fistula B/C” were younger, compared to the “no fistula” group. Tumors with morphology associated with worse prognosis, were more common in patients with pancreatic fistula. All the parameters were significantly correlated with fistula B/C and biochemical leak, especially the amylase drain level (Table 2).

According to the three-dimensional postoperative model, ROC AUC = 85% (Figure 1C and Table 4), the main general risk factors of pancreatic fistula B/C were BMI, age, tumor vascular invasion, and tumor size, Im = 20.7%, 17.9%, 14.3%, and 10%, respectively. Disease stage, tumor morphology, and pancreatic duct diameter were also important factors, Im = 9.3%, 8.5%, and 6%, respectively. The Ims of other parameters were below 5% (Figure 2C).

Similar results were obtained from the correlation analysis: Young age was more common in patients with biochemical leak and pancreatic fistula B/C development (Table 1 and Table 2). The model was also effective in distinguishing between the risk of pancreatic fistula B/C and biochemical leak, ROC AUC = 74% (Figure 1D).

Based on the 3-5 postoperative days data, the quality of fistula B/C prediction was higher, ROC AUC = 86% (Figure 1E). Similar to the binary model, the main risk factors were drain and blood amylase level 3-5 days after surgery, blood leukocytes, measured at 2-3 days, Im = 25%, 13.4%, and 12.4%, respectively. Age and BMI were also important factors, Im = 9.8% and 8.6%. Vascular invasion, tumor size, and disease stage were the next parameters sorted at the significance level, Im = 6%, 5.4%, and 5.4%, respectively. Importances, calculated for tumor morphology, pancreatic duct diameter, perineural invasion, enterostomy, Roux anastomosis, and blood vessel resection were less than 5% (Figure 2D).

We obtained low quality in the model to distinguish biochemical leak and fistula B/C after surgery, ROC AUC = 47% (Figure 1F). Therefore at 3-5 days after PD, biochemical leak and fistula B/C have the same predictors and a significant increase in pancreatic amylase drain level leads to subsequent fistula B/C.

We employed logistic regression, random forest, and CatBoost algorithms to develop models of POPF. Based on the ROC AUC metrics, the CatBoost ML algorithm was the most effective. The CatBoost model predicted fistula B/C and biochemical leak with high quality (> 70%)[28,38,52], ROC AUC = 74%-86%, based on pre- and intraoperative data with additional data, obtained 3-5 days after surgery. The quality is enough for risk factor detection and clinical implementation[30,42,43]. We provide results of the first implementation of the ML approach, based on the selection of algorithms and their hyperparameters for pancreatic fistula prediction and risk factor detection. Previous studies that aimed to extend ISGPF classification and scale risk factors, did not employ hyperparameter selection[15]. Usually, ML is used for predictive modeling; however, in our study, we also provide risk factor analysis.

Our study scaled 14 clinical parameters as risk factors for pancreatic fistula. We selected the main pre- and intraoperative prognostic factors of all the fistulas: Tumor vascular invasion, age, and BMI, ROC AUC = 74%. The ML model confirmed biochemical leak, blood and drain amylase level, and blood leukocytes as crucial predictors for subsequent fistula B/C, ROC AUC = 86%. Surgical techniques, tumor size, morphology, and pancreatic duct diameter less than 3 mm were insignificant.

Increases in amylase drain and blood levels after surgery were the main risk factors for the subsequent development of pancreatic fistulas B/C. Since 2016, the IGSPF has considered biochemical leak as a clinically insignificant condition[9,10]. We included biochemical leak in our novel model and showed that the increase in pancreatic amylase drain level and biochemical leak were associated with the development of fistulas with clinical symptoms. Thus, we consider it important to timely detect biochemical leak early after surgery to predict and prevent fistula grade B and C. These results prove the crucial role of pancreatic blood and drain amylase levels from an evidence-based point of view[14,21,53].

Young patient age was a significant risk factor for fistula development which was also confirmed in previously published results[7]. BMI and large tumor size were also significant in the models. There are a few published studies, dedicated to the significance of tumor size as a pancreatic fistula risk factor; however, similar results were obtained in a retrospective observational study by Mostafa et al[54]. The role of BMI is contradictory in different studies[16], and we proved its significance. Thus, we consider these parameters as preoperative risk factors.

According to the ML models and correlation analysis, perineural, and vascular invasion were associated with a better prognosis of pancreatic fistula. Similar results regarding vascular invasion were obtained in the retrospective multicenter observational study by Villodre et al[18]. We verified the clinical significance of these parameters and suggest perineural and vascular invasion should be evaluated in biopsy material, as prognostic factors of POPF. We did not find any publications dedicated to preoperative evaluation of perineural and vascular invasion, and these parameters are not highlighted in the clinical guidelines. Thus, we believe that our results will demonstrate their significance.

ML modeling results were confirmed by classical statistics, and correlation analysis, whereas some literature data are contradictory. Different studies consider high or low pancreatic duct diameter a risk factor[16,17]; the observations on BMI and surgical techniques are controversial[6,16,55]. Being important for ML model development, BMI was not correlated with pancreatic fistula (Kendall correlation, P < 0.05). Considering the controversial literature data[6,16], we suggest a complicated association between these parameters that is difficult to detect with the classical statistical analysis employed in previous studies. At the same time, ML modeling may stay challenging without a big dataset that is difficult to collect for pancreatic cancer[56,57].

The novelty of the study includes the implementation of a ML approach with a focus on medical data evaluation, based on algorithm selection. There are no previous publications describing three-dimensional ML models of POPF and the study of biochemical leak. We provide the results of ML modeling, based on pre- and intraoperative data with additional clinical information, 3-5 days after surgery.

This study is limited by its retrospective design, which may introduce selection bias. Additionally, the single-center nature of the dataset limits the generalizability of the findings. While the model demonstrated robust performance in internal validation, external validation in multicenter datasets is necessary to confirm its utility across diverse populations. We included only patients, who underwent PD and excluded patients with distal pancreatic cancer who may have a different prognosis. From a technical point of view, the workflow for risk factor analysis included Ims evaluation. If the Im of a parameter, such as the drain amylase level increases with a gap, all other Im values decrease about the gap[39] which may lead to bias.

This study highlights the key predictors of POPF and establishes a robust ML-based model for individualized risk prediction. The results of the risk factor analysis were confirmed by correlation analysis and indicated the main risk factors for this complication. Thus, young age and large tumor size are associated with fistula B/C and biochemical leak development. Blood and drain amylase level increases and biochemical leak are the major risk factors of subsequent fistula B/C development. By identifying high-risk individuals, the developed model has the potential to guide personalized management strategies for patients undergoing PD.

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55765] [Article Influence: 7966.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 2. | WHO. World health statistics 2020: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. [cited January 17, 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240005105. |

| 3. | Callery MP, Pratt WB, Vollmer CM Jr. Prevention and management of pancreatic fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:163-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lin JW, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Riall TS, Lillemoe KD. Risk factors and outcomes in postpancreaticoduodenectomy pancreaticocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:951-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Marchegiani G. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. HPB. 2019;21:S913-S914. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Machado NO. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatectomy: definitions, risk factors, preventive measures, and management-review. Int J Surg Oncol. 2012;2012:602478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vallance AE, Young AL, Macutkiewicz C, Roberts KJ, Smith AM. Calculating the risk of a pancreatic fistula after a pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17:1040-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula Definition. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3512] [Article Influence: 175.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 9. | Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, Del Chiaro M, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Fingerhut A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hackert T, Izbicki J, Lillemoe KD, Neoptolemos JP, Olah A, Schulick R, Shrikhande SV, Takada T, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vollmer CM, Wolfgang CL, Yeo CJ, Salvia R, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery. 2017;161:584-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3041] [Cited by in RCA: 2947] [Article Influence: 368.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 10. | Bassi C, Butturini G, Molinari E, Mascetta G, Salvia R, Falconi M, Gumbs A, Pederzoli P. Pancreatic fistula rate after pancreatic resection. The importance of definitions. Dig Surg. 2004;21:54-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jansen AC, van Aalst-Cohen ES, Hutten BA, Büller HR, Kastelein JJ, Prins MH. Guidelines were developed for data collection from medical records for use in retrospective analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:269-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khalil L, Huang Z, Zakka K, Jiang R, Penley M, Alese OB, Shaib WL, Wu C, Behera M, Reid MD, El-Rayes BF, Akce M. Survival and Prognostic Factors in Patients With Pancreatic Colloid Carcinoma Compared With Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2023;52:e75-e84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hirashita T, Ohta M, Tada K, Saga K, Takayama H, Endo Y, Uchida H, Iwashita Y, Inomata M. Prognostic factors of non-ampullary duodenal adenocarcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:743-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hackert T, Hinz U, Pausch T, Fesenbeck I, Strobel O, Schneider L, Fritz S, Büchler MW. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: We need to redefine grades B and C. Surgery. 2016;159:872-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bonsdorff A, Sallinen V. Prediction of postoperative pancreatic fistula and pancreatitis after pancreatoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy: A review. Scand J Surg. 2023;112:126-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zarzavadjian Le Bian A, Fuks D, Montali F, Cesaretti M, Costi R, Wind P, Smadja C, Gayet B. Predicting the Severity of Pancreatic Fistula after Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Overweight and Blood Loss as Independent Risk Factors: Retrospective Analysis of 277 Patients. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2019;20:486-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Peng YP, Zhu XL, Yin LD, Zhu Y, Wei JS, Wu JL, Miao Y. Risk factors of postoperative pancreatic fistula in patients after distal pancreatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Villodre C, Del Río-Martín J, Blanco-Fernández G, Cantalejo-Díaz M, Pardo F, Carbonell S, Muñoz-Forner E, Carabias A, Manuel-Vazquez A, Hernández-Rivera PJ, Jaén-Torrejimeno I, Kälviäinen-Mejia HK, Rotellar F, Garcés-Albir M, Latorre R, Longoria-Dubocq T, De Armas-Conde N, Serrablo A, Esteban Gordillo S, Sabater L, Serradilla-Martín M, Ramia JM. Textbook outcome in distal pancreatectomy: A multicenter study. Surgery. 2024;175:1134-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | El Nakeeb A, El Sorogy M, Ezzat H, Said R, El Dosoky M, Abd El Gawad M, Elsabagh AM, El Hanafy E. Predictors of long-term survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for peri-ampullary adenocarcinoma: A retrospective study of 5-year survivors. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2018;17:443-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | El Nakeeb A, El Shobary M, El Dosoky M, Nabeh A, El Sorogy M, El Eneen AA, abu Zeid M, Elwahab MA. Prognostic factors affecting survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (single center experience). Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:1426-1438. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Liu Y, Li Y, Wang L, Peng CJ. Predictive value of drain pancreatic amylase concentration for postoperative pancreatic fistula on postoperative day 1 after pancreatic resection: An updated meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Villafane-Ferriol N, Shah RM, Mohammed S, Van Buren G 2nd, Barakat O, Massarweh NN, Tran Cao HS, Silberfein EJ, Hsu C, Fisher WE. Evidence-Based Management of Drains Following Pancreatic Resection: A Systematic Review. Pancreas. 2018;47:12-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Douglas MJ, Callcut R, Celi LA, Merchant N. Interpretation and Use of Applied/Operational Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2023;103:317-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yang F, Windsor JA, Fu DL. Optimizing prediction models for pancreatic fistula after pancreatectomy: Current status and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:1329-1345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Sasubilli G, Kumar A. Machine Learning and Big Data Implementation on Health Care data. 2020 4th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS) 2020; May 13-15; Madurai, India. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Edsjö A, Holmquist L, Geoerger B, Nowak F, Gomon G, Alix-Panabières C, Ploeger C, Lassen U, Le Tourneau C, Lehtiö J, Ott PA, von Deimling A, Fröhling S, Voest E, Klauschen F, Dienstmann R, Alshibany A, Siu LL, Stenzinger A. Precision cancer medicine: Concepts, current practice, and future developments. J Intern Med. 2023;294:455-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Corny J, Rajkumar A, Martin O, Dode X, Lajonchère JP, Billuart O, Bézie Y, Buronfosse A. A machine learning-based clinical decision support system to identify prescriptions with a high risk of medication error. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:1688-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine Learning in Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1347-1358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1274] [Cited by in RCA: 1591] [Article Influence: 265.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cuocolo R, Caruso M, Perillo T, Ugga L, Petretta M. Machine Learning in oncology: A clinical appraisal. Cancer Lett. 2020;481:55-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bertsimas D, Wiberg H. Machine Learning in Oncology: Methods, Applications, and Challenges. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:885-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lee W, Park HJ, Lee HJ, Song KB, Hwang DW, Lee JH, Lim K, Ko Y, Kim HJ, Kim KW, Kim SC. Deep learning-based prediction of post-pancreaticoduodenectomy pancreatic fistula. Sci Rep. 2024;14:5089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ashraf Ganjouei A, Romero-Hernandez F, Wang JJ, Casey M, Frye W, Hoffman D, Hirose K, Nakakura E, Corvera C, Maker AV, Kirkwood KS, Alseidi A, Adam MA. A Machine Learning Approach to Predict Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula After Pancreaticoduodenectomy Using Only Preoperatively Known Data. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:7738-7747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Verma A, Balian J, Hadaya J, Premji A, Shimizu T, Donahue T, Benharash P. Machine Learning-based Prediction of Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula Following Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2024;280:325-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Shen Z, Chen H, Wang W, Xu W, Zhou Y, Weng Y, Xu Z, Deng X, Peng C, Lu X, Shen B. Machine learning algorithms as early diagnostic tools for pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy and guide drain removal: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2022;102:106638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, Behrman SW, Benson AB, Cardin DB, Chiorean EG, Chung V, Czito B, Del Chiaro M, Dillhoff M, Donahue TR, Dotan E, Ferrone CR, Fountzilas C, Hardacre J, Hawkins WG, Klute K, Ko AH, Kunstman JW, LoConte N, Lowy AM, Moravek C, Nakakura EK, Narang AK, Obando J, Polanco PM, Reddy S, Reyngold M, Scaife C, Shen J, Vollmer C, Wolff RA, Wolpin BM, Lynn B, George GV. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:439-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 689] [Article Influence: 172.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Johnson JM, Khoshgoftaar TM. Survey on deep learning with class imbalance. J Big Data. 2019;6:27. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 37. | Krupinova JA, Elfimova AR, Rebrova OY, Voronkova IA, Eremkina AK, Kovaleva EV, Maganeva IS, Gorbacheva AM, Bibik EE, Deviatkin AA, Melnichenko GA, Mokrysheva NG. Mathematical model for preoperative differential diagnosis for the parathyroid neoplasms. J Pathol Inform. 2022;13:100134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Geurts P, Ernst D, Wehenkel L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach Learn. 2006;63:3-42. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3062] [Cited by in RCA: 1871] [Article Influence: 98.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The Elements of Statistical Learning. Springer Series in Statistics 2009. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 40. | Sharchilev B, Ustinovsky Y, Serdyukov P, de Rijke M. Finding Influential Training Samples for Gradient Boosted Decision Trees. 2018. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 41. | Rigatti SJ. Random Forest. J Insur Med. 2017;47:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 56.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Hancock JT, Khoshgoftaar TM. CatBoost for big data: an interdisciplinary review. J Big Data. 2020;7:94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 54.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Berrar D. Cross-Validation. In: Encyclopedia of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology. Elsevier, 2019: 542-545. |

| 44. | Kohavi R. A Study of Cross-Validation and Bootstrap for Accuracy Estimation and Model Selection. In: IJCAI International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 1995: 1137-1143. |

| 45. | Veena Kumari HM, Suresh DS, Dhananjaya PE. Clinical Data Analysis and Multilabel Classification for Prediction of Dengue Fever by Tuning Hyperparameter using GridsearchCV. 2022 14th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (CICN) 2022; 04-06. Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 46. | Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014;34:502-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1208] [Cited by in RCA: 1627] [Article Influence: 147.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Sakamoto T, Goto T, Fujiogi M, Kawarai Lefor A. Machine learning in gastrointestinal surgery. Surg Today. 2022;52:995-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Wallace ML, Mentch L, Wheeler BJ, Tapia AL, Richards M, Zhou S, Yi L, Redline S, Buysse DJ. Use and misuse of random forest variable importance metrics in medicine: demonstrations through incident stroke prediction. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2023;23:144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Matsuo R, Yamazaki T, Suzuki M, Toyama H, Araki K. A random forest algorithm-based approach to capture latent decision variables and their cutoff values. J Biomed Inform. 2020;110:103548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Kanerva N, Kontto J, Erkkola M, Nevalainen J, Männistö S. Suitability of random forest analysis for epidemiological research: Exploring sociodemographic and lifestyle-related risk factors of overweight in a cross-sectional design. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46:557-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Akarachantachote N, Chadcham S, Saithanu K. Cutoff Threshold of Variable Importance in Projection for Variable Selection. Int J of Pure and Appl Math. 2014;94. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Sidey-Gibbons JAM, Sidey-Gibbons CJ. Machine learning in medicine: a practical introduction. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 614] [Cited by in RCA: 556] [Article Influence: 92.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Schuh F, Mihaljevic AL, Probst P, Trudeau MT, Müller PC, Marchegiani G, Besselink MG, Uzunoglu F, Izbicki JR, Falconi M, Castillo CF, Adham M, Z'graggen K, Friess H, Werner J, Weitz J, Strobel O, Hackert T, Radenkovic D, Kelemen D, Wolfgang C, Miao YI, Shrikhande SV, Lillemoe KD, Dervenis C, Bassi C, Neoptolemos JP, Diener MK, Vollmer CM Jr, Büchler MW. A Simple Classification of Pancreatic Duct Size and Texture Predicts Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula: A classification of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery. Ann Surg. 2023;277:e597-e608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 62.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Mostafa A, Habeeb TA, Neri V, Elshahidy TM, A Fiad A. Risk factors for postoperative pancreatic fistula following non-traumatic, pancreatic surgery. Retrospective observational study. Ann Ital Chir. 2023;94:435-442. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Wang H, Shao Z, Guo SW, Jing W, Song B, Li G, He TL, Zhou XY, Zhang YJ, Zhou YQ, Hu XG, Jin G. [Analysis of prognostic factors for hyperamylasemia following pancreaticoduodenectomy]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2019;57:534-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Gaddam S, Abboud Y, Oh J, Samaan JS, Nissen NN, Lu SC, Lo SK. Incidence of Pancreatic Cancer by Age and Sex in the US, 2000-2018. JAMA. 2021;326:2075-2077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12667] [Cited by in RCA: 15297] [Article Influence: 3059.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |