Published online Mar 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i3.99129

Revised: November 22, 2024

Accepted: December 19, 2024

Published online: March 15, 2025

Processing time: 214 Days and 21 Hours

Acute cholecystitis due to unintended cystic artery embolism is an uncommon and mostly self-limiting complication after transarterial chemoembolization procedure for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Usually, conservative management is sufficient for complete recovery of patients who develop this complication. If conservative treatment is ineffective, urgent surgical inter

This article reports a rare and serious case of acute cholecystitis complicated by gallbladder necrosis and biliary peritonitis, which was initially treated conservatively but eventually necessitated emergency laparotomy. The patient initially presented with equivocal symptoms of fever and upper abdominal pain and dis

After cholecystostomy, the patient showed symptom relief and was discharged, surviving 11 months post-stage IIIB liver cancer diagnosis.

Core Tip: Acute cholecystitis due to cystic artery embolism after transarterial chemoembolization is an uncommon and mostly self-limiting complication. We present a rare case of acute cholecystitis complicated by gallbladder necrosis and biliary peritonitis, which required emergency laparotomy and cholecystostomy creation.

- Citation: Chen YF, Lin ZY, Chen LT, Zhang Y, Du ZQ. Cystic artery embolism after transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(3): 99129

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i3/99129.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i3.99129

Worldwide, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks as the 6th most common cancer as well as the 4th leading cause of cancer-related mortality[1]. A range of treatment modalities, ranging from surgical resection to locoregional and systemic therapies, offer options for curative or palliative treatment across different stages of HCC[1]. In particular, the treatment modalities available for unresectable HCC include vascular interventions, local ablative techniques, radiotherapy, targeted therapies, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy[2]. The utilization of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) has demonstrated enhanced survival rates in patients with unresectable liver cancer, establishing it as an efficacious the

Persistent left upper abdominal discomfort for 1 month, followed by fever and abdominal distension 2 weeks after TACE.

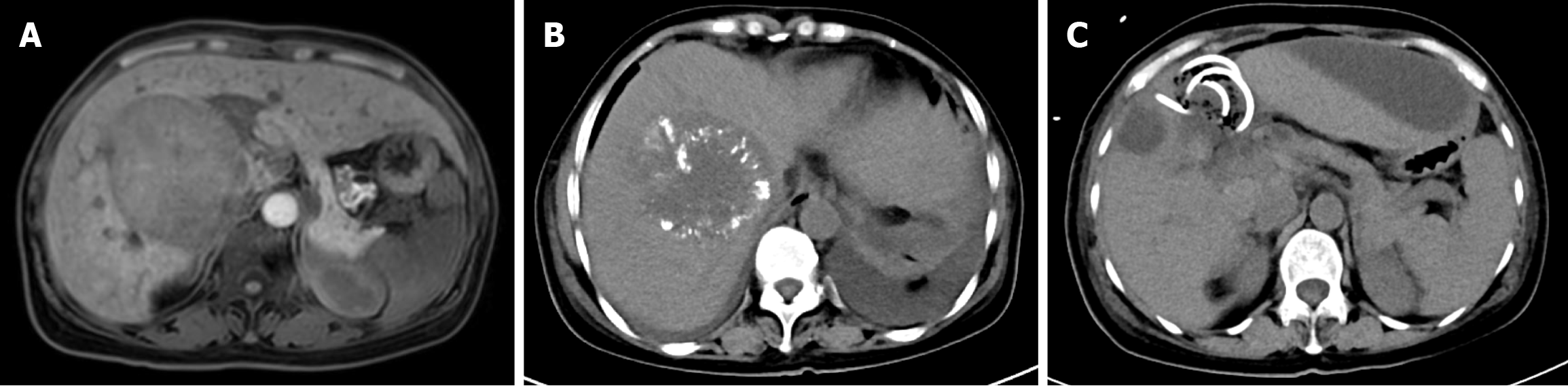

The patient, a 51-year-old woman, was admitted to Shaanxi Provincial People's Hospital due to recurrent left upper abdominal discomfort for a duration of 1 month. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the upper abdomen revealed a space-occupying lesion measuring 7.4 cm × 9.1 cm × 7.1 cm in the anterior right quadrant of the liver, with invasion of the middle hepatic vein (Figure 1A). The blood test results showed elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 120 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 128 U/L, positive hepatitis B surface antigen, alpha fetoprotein (AFP) at 6.05 ng/mL, and CA19-9 at 201.23 U/mL. Puncture histopathology indicated necrotic tissue with a few degenerated hepatocytes present. No nodal involvement or distant metastasis was found. The initial diagnosis for the patient was HCC. TNM stage T4N0M0, which corresponds to AJCC stage IIIB. This was associated with hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis.

The treatment option consisted of sorafenib combined with TACE. Following the 3rd TACE procedure, the patient presented with unexplained high fever, recurrent upper abdominal pain, and abdominal distention without nausea or vomiting. Laboratory results revealed a white blood cell count of 8.53 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage of 80.9%, total bilirubin (TBiL) level of 11.29 μmol/L, and ALT level of 63 U/L (Table 1). Abdominal ultrasound examination did not reveal any obvious abnormalities. On the 10th day after the operation, an abdominal CT scan showed a round low-density shadow in the gallbladder fossa accompanied by gas accumulation and surrounding exudation (Figure 1B). Cystic artery embolism leading to acute cholecystitis was considered as a potential complication - a rare and serious occurrence following TACE procedures. Subsequently, percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGD) was performed under local anesthesia to address this complication. During the procedure, no signs of perforation were observed and clear visibility of the gallbladder was maintained. After placement of a drainage tube, minimal bilious drainage contents were obtained, which did not significantly improve infection markers. Furthermore, bedside ultra

| Blood test (reference value) | 1 week after TACE | 2 weeks after TACE | Before exploratory laparotomy | 2 days after surgery | 1 week after surgery |

| Hb (115-150 g/L) | 111 | 115 | 86 | 73 | 112 |

| PLT (125-350 × 109/L) | 75 | 113 | 190 | 152 | 217 |

| WBC (3.5-9.5 × 109/L) | 8.53 | 13.12 | 15.34 | 15.11 | 10.69 |

| N (0.4-0.75) | 0.809 | 0.925 | 0.83 | 0.874 | 0.77 |

| ALP (50-135 U/L) | 122 | 160 | 157 | 117 | 443 |

| TBil (0-23 umol/L) | 11.29 | 19.93 | 31.17 | 16 | 35.9 |

| ALB (40-55 g/L) | 22.8 | 23.6 | 36.9 | 30.2 | 42.4 |

| ALT (7-40 U/L) | 63 | 118 | 37 | 30 | 19 |

| AST (13-35 U/L) | 44 | 77 | 29 | 30 | 27 |

| GGT (7-45 U/L) | 76 | 89 | 84 | 48 | 250 |

Two weeks post-TACE, the patient presented with sudden abdominal distension, exacerbated abdominal pain, and evident signs of peritonitis. Blood analysis revealed a white blood cell count of 15.34 × 109/L, with neutrophils accounting for 83% (Table 1). Urgent bedside ultrasound examination demonstrated multiple areas of peritoneal fluid accumulation that progressively increased in size, leading to a suspected diagnosis of biliary peritonitis.

The patient had no significant past medical history, with no history of liver disease, diabetes, hypertension, or other chronic conditions.

The patient led a regular lifestyle with no harmful habits, and had no history of smoking or alcohol consumption. There was no history of long-term medication use. There was no family history of liver disease, malignancies, or hereditary diseases, and no history of hepatitis or liver cirrhosis in direct relatives.

The patient was conscious but in a poor mental state. There was no significant change in weight. The conjunctiva was not jaundiced, the oral cavity was clean, and the gingiva showed no signs of bleeding. There was no enlargement of bilateral cervical lymph nodes, the thyroid was not enlarged, and the trachea was in the midline. Breathing was stable, and bilateral lung sounds were clear, with no wheezing or crackles. The heart rate was regular, and no murmurs were heard on cardiac auscultation. The abdomen was distended, with tympanic percussion and tenderness on palpation mainly in the right upper quadrant, without rebound tenderness. The liver edge was palpable, firm in texture, and tender. No ascites was detected, and bowel sounds were normal. There was no obvious splenomegaly. There was no edema in the lower extremities, and the limbs were freely movable. No other abnormalities were noted on examination.

At admission, the patient presented with elevated liver enzymes (ALT and AST), mild bilirubin elevation, and positive hepatitis B surface antigen, indicating liver damage and hepatitis B virus infection. The tumor markers AFP and CA19-9 were also elevated, suggesting the possibility of HCC.

After the third TACE treatment, the patient showed improvement in TBiL, with a reduction in ALT levels. However, blood tests still indicated mild infection, with white blood cell count and neutrophil percentage remaining elevated, suggesting an ongoing inflammatory response.

Ten days post-procedure, the patient's white blood cell count significantly increased, with a higher percentage of neutrophils, indicating acute infection. Although ALT levels remained stable, the patient continued to show signs of infection and inflammation, likely due to complications from the procedure.

Imaging at admission: A space-occupying lesion was identified in the anterior right quadrant of the liver, measuring 7.4 cm × 9.1 cm × 7.1 cm, with invasion of the middle hepatic vein (Figure 1A). This imaging finding suggests a possible HCC with vascular invasion.

Imaging after the 3rd TACE treatment (10 days post-procedure): A round low-density shadow was observed in the gallbladder fossa, accompanied by gas accumulation and surrounding exudation (Figure 1B). This suggests acute cholecystitis with gas formation, possibly due to complications after TACE, such as gallbladder perforation or biliary infection.

Imaging after complications (2 weeks post-procedure): Multiple areas of peritoneal fluid accumulation were observed, progressively increasing in size, leading to a suspected diagnosis of biliary peritonitis. This imaging finding further supports the diagnosis of peritonitis, likely caused by biliary tract infection.

The patient is a middle-aged female with a confirmed diagnosis of HCC. Following the third session of TACE, she developed acute cholecystitis secondary to cystic artery embolization. Subsequent PTGD was performed, but her symptoms worsened, with laboratory findings indicating leukocytosis and ultrasound revealing signs of peritonitis. Biliary peritonitis was ultimately suspected.

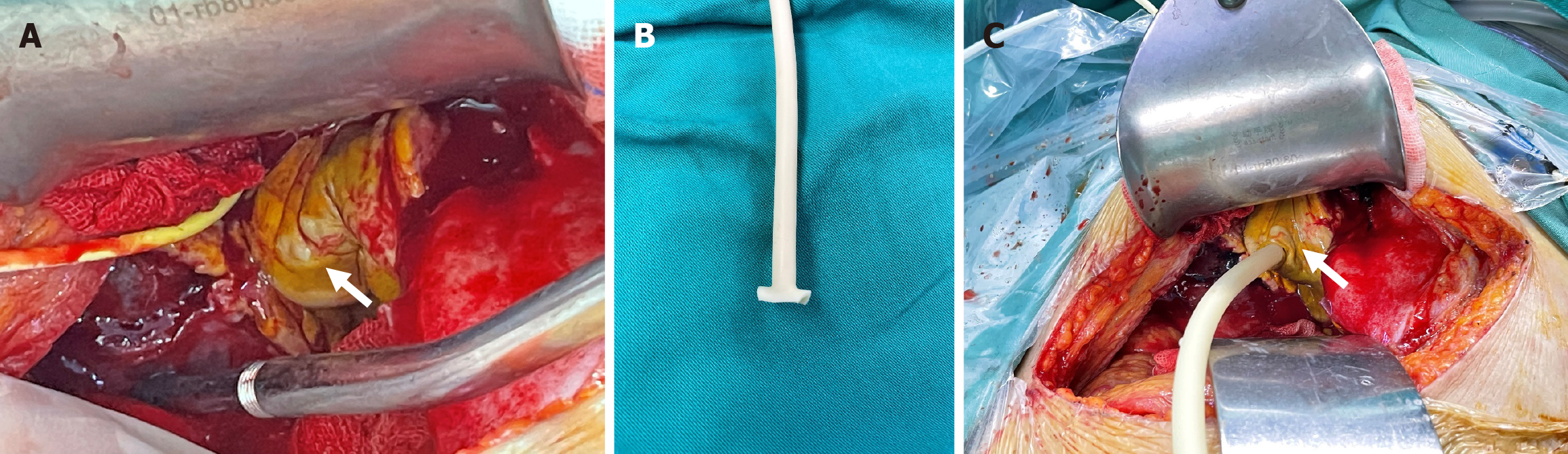

Consequently, an emergency laparotomy was performed, revealing severe local inflammation and necrosis of the gallbladder along with a distorted anatomy in the hepatic hilar region. Due to the distorted anatomy of the Calot’s triangle which increases risk of biliary tract damage if cholecystectomy was performed, the surgical intervention chosen involved irrigation and debridement as well as cholecystostomy (Figure 1C and Figure 2).

Following surgery, the patient experienced symptom relief and was discharged two weeks later with a drainage tube. The patient received regular post-discharge follow-up and subsequently required repeated hospitalizations due to episodes of cholangitis and blockage of the drainage tube. Follow-up imaging revealed progressive tumor growth, accompanied by deterioration in liver function and overall condition. Ultimately, the patient succumbed to multiple organ failure resulting from advanced liver cancer 11 months after initial diagnosis.

TACE is the recommended treatment modality for patients with inoperable HCC with preserved liver function[3,7,10,13,14]. It involves two main mechanisms to eliminate tumor cells: One the one hand, a chemotherapeutic agent, usually doxorubicin, exerts cytotoxic effects on tumor cells; on the other hand, embolization of the feeding artery of the tumor causes tumor cells to undergo ischemia and necrosis[8,13]. In terms of embolic agent selection, TACE with lipiodol mixed with anticancer drugs and GS particles, transarterial embolization with GS particles (GS-TAE), transarterial radioembolization with yttrium-90 microspheres (TARE), and TACE with drug-loaded microspheres (doxorubicin) have been reported to enhance tumor response and mitigate severe complications[13,15-20].

Complications from TACE are infrequent and predominantly benign[8]; studies have reported a range of such serious but rare complications including hepatic abscess leading to sepsis, bile duct necrosis, biloma formation, biliary stricture, intrahepatic bile duct dilation, hepatic infarction, tumor rupture, gastric mucosa injury and gastrointestinal bleeding, acute pancreatitis, liver rupture, pulmonary embolism, femoral artery pseudoaneurysm, acute tumor lysis syndrome, and acute cholecystitis[4,6,7,10,16,21-23]. Among these, acute cholecystitis is a relatively more common complication and its incidence ranges from 0.3% to 10%[6,10,12,13,20,23-26]. The majority of patients experiencing complications exhibited Child-Pugh Class B liver function and had a model for end-stage liver disease score of at least 9[27]. Multiple administrations can also increase the risk of acute cholecystitis[13]. Our patient underwent three TACE procedures that could have put her at higher risk of the complication. The risk of unintended embolization of the cystic artery can be reduced through techniques like highly selective microcatheter embolization[12].

In the case of radioembolization (TARE), a higher incidence of cholecystitis and other gallbladder related complications has been reported, at 2.4%-24%[12]. In TARE, cholecystitis is caused by radiation rather than ischemia[12].

The main cause of acute cholecystitis after TACE is likely from technical problems, reflux of embolized material, or embolization of the cystic artery leading to its occlusion[3,9]. Hence, it is crucial to tailor the choice of embolization and chemotherapy drugs to the patient and ensure precise placement of the catheter[7,27]. Despite that, the backflow of embolized material may occur even when a super-selective catheter is placed away from the origin of the cystic artery[4].

Because the cystic artery is the primary source of blood supply to the gallbladder, and, unlike the liver, the gallbladder does not have a dual blood supply[4], embolism of the cystic artery can result in gallbladder ischemia, leading to acute cholecystitis, which, if unresolved, can progress to gallbladder necrosis[4,9].

The cystic artery primarily originates from the right hepatic artery[28], thus when employing the proximal right hepatic artery (or proper hepatic artery) approach, there is a higher likelihood of cystic artery embolization[13,29]. Selective techniques comes with a lower risk of cholecystitis[13]; however, it has been reported that chemoembolization procedures in segments IV and V of the liver may also increase risk of cholecystitis and hence may require additional precaution[13]. At the same time, rare anatomical variations to the origin of the cystic artery also exist, such as that arising from the left hepatic artery, common hepatic artery, or the superior mesenteric artery[4,13]. In these cases, embolization of the left hepatic artery may have an increased risk of occluding the cystic artery.

Patients who develop acute cholecystitis post-TACE may report symptoms of right upper abdominal pain (which can last from a few days to a month) and fever and show signs of guarding or tenderness[4,7,13]. Severe abdominal pain and/or persistent symptoms despite treatment may suggest more serious complications like gallbladder necrosis or perforation[4,22]. These non-specific symptoms make diagnosis difficult because most patients will often experience such nonspecific symptoms like fever, fatigue, abdominal pain (in the right upper quadrant), nausea, vomiting and ileus following TACE, and this has been has been extensively reported in the literature as the self-limiting “post-embolisation syndrome”[7,10,17,22], which can affect up to 20%-90% of patients[8]. Other complications such as hepatic abscess and hepatic infarction may also present similarly, with abdominal pain and fever as the main symptoms[9]. Yet, clinicians involved in the care of patients post-TACE should be more cautious of acute cholecystitis in particular in patients with right-sided HCC who report such symptoms post-TACE, especially if they persist.

It is important to note that most of the complications occur within a 2-week period following TACE[7]. Early recognition and prompt initiation of treatment are important because delayed recognition can carry the risk of progression to gangrenous cholecystitis and gallbladder necrosis[7,12,22]. Our patient presented initially with similar symptoms as those in the literature, with high fever, abdominal pain, and abdominal distention, which could have prompted a consideration of acute cholecystitis; however, there were insufficient clues, with laboratory indicators unspecific and imaging inconclusive. The development of more severe symptoms 2 weeks after the procedure, however, was suggestive of more serious complications, which was confirmed to be biliary peritonitis by bedside ultrasound.

Various imaging modalities may be necessary to aid the diagnosis of patients with acute cholecystitis (as well as other complications), including CT, MRI, digital subtraction angiography, and ultrasound[7,30]. CT and ultrasound findings of a dilated gallbladder with wall thickening may be suggestive of cholecystitis and are described in many reports[9,13,31]; other CT criteria for cholecystitis may include presence of “sandwich-like layering of the gallbladder wall” suggesting submucosal edema, “gas in the gallbladder”, “pericholecystic stranding” in fat surrounding gallbladder, “indistinct interface of gallbladder wall and adjacent liver”, and presence of “pericholecystic abscess”, as well as deposition of “lipiodol in the walls of the gallbladder”[31]. Discontinuous enhancement of the gallbladder wall seen on CT can suggest necrosis of the gallbladder[9], while interruption of the gallbladder wall together with fluid collection originating from the gallbladder (and sometimes gas) may suggest a perforated gallbladder[22]. In our case, initial ultrasound did not show any abnormalities; however, on the 10th day after the procedure, abdominal CT showed a round low-density shadow in the gallbladder fossa accompanied by gas accumulation and surrounding exudation, which can suggest cholecystitis.

In terms of laboratory indicators, white blood cell count, neutrophil percentage, TBiL, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), procalcitonin, and other indicators can serve as markers for acute cholecystitis. Elevated white blood cell counts and an increase in neutrophil percentage can suggest the possibility of an infection[10]. However, leukocytosis and raised transaminases are also reported in post-embolisation syndrome[8,20,25,31]. These changes are probably due to necrosis of tumor cells and surrounding healthy hepatocytes, causing lysis and release of intracellular enzymes[4,31]. Thus, such indicators may not differentiate patients with acute cholecystitis from those without[31]. In our patient, initial laboratory values were inconclusive with leucocyte count (8.53 × 109/L) and ALP (122 U/L) in the normal range and slight elevation of neutrophil ratio (80.9%); when her symptoms worsened two weeks after TACE, laboratory values also became more suggestive of a serious complication with a marked increase in leucocytes (13.12 × 109/L), neutrophil percentage (92.5%), as well as ALP value (160 U/L).

HCC complicated with cholecystitis can impact the treatment and prognosis of patients[12]. However, as a complication of TACE, it is generally self-limiting for most patients[9,31], and most achieve complete recovery with conservative management[9,12,29,31]. Close observation, fasting, and intravenous administration of antibiotics such as piperacillin with tazobactam are usually sufficient[9,32].

However, a small subset may exhibit worsening local inflammation of the gallbladder leading to gallbladder necrosis and perforation accompanied by acute peritonitis[12,13,22]. Gangrenous cholecystitis, emphysematous cholecystitis, and lipoidal cholecystitis are other serious complications[13,31]. In such cases where conservative treatment proves ineffec

| Ref. | Findings | Contributions |

| Marcacuzco Quinto et al[6] | Out of the 196 patients with liver tumors who had undergone 322 TACE procedures, 4 developed acute cholecystitis | To review the complications following TACE for liver tumors |

| Xue et al[10] | Severe complications were few (4.9%), acute cholecystitis (n = 4 in 511) | A large cohort study of TACE for huge HCC with a diameter over 10 cm |

| Cosgrove et al[14] | Severe procedure-related complications were seen in 3.2% (cholecystitis, n = 1 in 62 patients) | An open-label study of 62 patients with DEB-TACE for unresectable HCC |

| Dhamija et al[8] | Biliary complications of various severities developed in 6 (3.6%) patients, leading to an incidence of 1.9% (6/305) | The incidence and presentation of biliary complications following TACE in patients with HCC |

| Tu et al[7] | The incidence was 2.1% per patient and 0.84% per TAE/TACE procedure. The complications included cholecystitis (n = 2). Major complications are mostly benign, but some are lethal | The incidence and outcome of major complications following conventional TAE/TACE therapy for HCC |

| Tarazov et al[30] | Serious ischemic complications of TACE occur in about 5% of patients and can be successfully managed without open surgery | The frequency, character, methods of treatment, and outcome of ischemic complications after TACE |

| Jayakrishnan et al[12] | Hepatic artery-based therapies carry a risk of cholecystitis (0.02%-24%), although the risk is reduced with selective catheterization | Review of the impact of antineoplastic therapies on the risk for cholelithiasis and acute cholecystitis |

| Malagari et al[26] | Severe procedure-related complications were seen in 4.2% (cholecystitis: n = 1; liver abscess: n = 1; pleural effusion: n = 1) | The results of segmental transcatheter arterial chemoembolization with doxorubicin-loaded DC bead in the treatment of HCC in non-surgical candidates |

| Biselli et al[23] | A significantly more favorable survival was observed for TACE-treated patients compared with IAC-treated patients; the side effect after the intraarterial procedure was chemical cholecystitis (8%) | TACE and IAC have a primary role in treating patients with unresectable HCC larger than 5 cm |

| Chen et al[2] | Metaanalysis provides preliminary evidence for the comparative safety and efficacy of HAIC and TACE combined with sorafenib, and indicates the dominance of HAICoxaliplatin in HCC interventional therapy | A systematic review and network metaanalysis of comparative effectiveness of interventional therapeutic modalities for unresectable HCC |

| Hidaka et al[17] | Combined therapy involving bland GS-TAE followed by Lip-TACE can be performed safely and may improve survival in patients with huge HCCs. Severe adverse events were seen in two patients, acute cholecystitis and tumor rupture (n = 21) | To assess the efficacy of combined therapy involving bland TAE using gelatin sponge particles followed by TACE using lipiodol mixed with anticancer agents and GS particles |

| Llovet and Bruix[3] | Sensitivity analysis showed a significant benefit of chemoembolization with cisplatin or doxorubicin but none with embolization alone | Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable HCC, and chemoembolization improves survival |

| Monier et al[29] | DEB-TACE was associated with increased hepatic toxicities compared to conventional TACE | Comparison between drug-eluting beads and lipiodol emulsion in liver and biliary damages following TACE of HCC |

| Wagnetz et al[31] | There was a 49% incidence of acute cholecystitis for TACE of HCC, and a lobar TACE of the right hepatic artery likely carries the highest risk of post-TACE cholecystitis | Acute ischemic cholecystitis is self-limiting and does not seem to require any intervention or surgery |

| Karaman et al[13] | The possibility of cholecystitis is always remembered during TACE-DEB for tumors in segments IV and/or V | A case of ischemic cholecystitis after DEB-TACE that required cholecystectomy |

| Karavias et al[11] | Super selective embolization significantly reduces the risk of cholecystitis. In most cases, management is conservative and only severe cases require further intervention | Gangrenous cholecystitis related to TACE treatment for HCC |

| Chung et al[20] | Important predisposing factors were major portal vein obstruction, compromised hepatic functional reserve, biliary obstruction, previous biliary surgery, excessive amount (> 20 mL) of iodized oil, hepatic arterial occlusion after repeated transcatheter oily chemoembolization (TOCE), and nonselective embolization | The major complications and their predisposing factors in TOCE for hepatic tumors |

| Kim et al[15] | Adjustments in the amounts of iodized oil or gelatin sponge particles and in the sites of embolization may reduce ischemic biliary injuries after TACE | The exact pathogenic mechanisms and clinical implications of the ischemic bile duct injury after TACE in patients with HCC |

| Song et al[21] | The biliary abnormality prone to ascending biliary infection was the most important predisposing factor to the development of liver abscess after TOCE | The incidence, predisposing factors for, and clinical outcome of liver abscess developing in patients with hepatic tumors after TOCE |

| Vasudevan et al[9] | The differential diagnosis in a patient with abdominal pain after TACE including post-embolization syndrome and, less commonly, hepatic abscess formation, one must consider cholecystitis especially for right-sided hepatic tumors | A case of acute ischemic cholecystitis following DEB-TACE |

| Lim et al[22] | The presence of gallbladder perforation must be recognized in patients with persisting symptoms and imaging evidence | A rare but serious complication: Gallbladder perforation following TACE |

| Kuroda et al[32] | Patients with post-TAE infarction of the gallbladder can be treated conservatively | Gallbladder infarction developing after TAE in patients with malignant hepatic tumors was studied |

| Sun et al[4] | If a hepatic resection is carried out after TACE, the gallbladder should be removed simultaneously. In addition, once a patient has developed an infarcted gallbladder, a cholecystectomy becomes necessary | The incidence, diagnosis, treatment, outcome, and mechanism of hepatic and biliary damage after TACE for malignant hepatic tumors |

In the case that we report, the patient presented with localized gallbladder necrosis accompanied by peritonitis following ectopic embolization of the cystic artery using lipiodol embolization. Following cholecystostomy treatment, the patient experienced symptom relief and was subsequently discharged. Ultimately, the patient achieved a survival of 11 months after being diagnosed with stage IIIB liver cancer.

We thank supports from the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery of the Shaanxi Provincial People's Hospital and Professor Rong-Qian Wu for his contribution to the language aspect of the draft.

| 1. | Brown ZJ, Tsilimigras DI, Ruff SM, Mohseni A, Kamel IR, Cloyd JM, Pawlik TM. Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:410-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Chen XL, Yu HC, Fan QG, Yuan Q, Jiang WK, Rui SZ, Zhou WC. Comparative effectiveness of interventional therapeutic modalities for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Oncol Lett. 2022;24:366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2207] [Cited by in RCA: 2271] [Article Influence: 103.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sun Z, Li G, Ai X, Luo B, Wen Y, Zhao Z, Dong S, Guan J. Hepatic and biliary damage after transarterial chemoembolization for malignant hepatic tumors: incidence, diagnosis, treatment, outcome and mechanism. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;79:164-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Boteon APCDS, Boteon YL, Vinuela EF, Derosas C, Mergental H, Isaac JR, Muiesan P, Mehzard H, Ma YT, Shah T, Mirza DF, Perera MTPR. The impact of transarterial chemoembolization induced complications on outcomes after liver transplantation: A propensity-matched study. Clin Transplant. 2018;32:e13255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Marcacuzco Quinto A, Nutu OA, San Román Manso R, Justo Alonso I, Calvo Pulido J, Manrique Municio A, García-Sesma Á, Loinaz Segurola C, Martínez Caballero J, Jiménez Romero LC. Complications of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in the treatment of liver tumors. Cir Esp (Engl Ed). 2018;96:560-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tu J, Jia Z, Ying X, Zhang D, Li S, Tian F, Jiang G. The incidence and outcome of major complication following conventional TAE/TACE for hepatocellular carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dhamija E, Paul SB, Gamanagatti SR, Acharya SK. Biliary complications of arterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:1169-1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vasudevan A, Spanger M, Lubel JS. Abdominal pain following drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolisation. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2015;5:105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xue T, Le F, Chen R, Xie X, Zhang L, Ge N, Chen Y, Wang Y, Zhang B, Ye S, Ren Z. Transarterial chemoembolization for huge hepatocellular carcinoma with diameter over ten centimeters: a large cohort study. Med Oncol. 2015;32:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Karavias D, Kourea H, Sotiriadi A, Karnabatidis D, Karavias D. Gangrenous Cholecystitis Related to Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization (TACE) Treatment for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:2093-2095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jayakrishnan TT, Groeschl RT, George B, Thomas JP, Clark Gamblin T, Turaga KK. Review of the impact of antineoplastic therapies on the risk for cholelithiasis and acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:240-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Karaman B, Battal B, Ören NC, Üstünsöz B, Yağci G. Acute ischemic cholecystitis after transarterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads. Clin Imaging. 2012;36:861-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cosgrove DP, Reyes DK, Pawlik TM, Feng AL, Kamel IR, Geschwind JF. Open-Label Single-Arm Phase II Trial of Sorafenib Therapy with Drug-eluting Bead Transarterial Chemoembolization in Patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Clinical Results. Radiology. 2015;277:594-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Atassi B, Bangash AK, Lewandowski RJ, Ibrahim S, Kulik L, Mulcahy MF, Murthy R, Ryu RK, Sato KT, Miller FH, Omary RA, Salem R. Biliary sequelae following radioembolization with Yttrium-90 microspheres. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:691-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hidaka T, Anai H, Sakaguchi H, Sueyoshi S, Tanaka T, Yamamoto K, Morimoto K, Nishiofuku H, Maeda S, Nagata T, Kichikawa K. Efficacy of combined bland embolization and chemoembolization for huge (≥10 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2021;30:221-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Klompenhouwer EG, Dresen RC, Verslype C, Laenen A, De Hertogh G, Deroose CM, Bonne L, Vandevaveye V, Maleux G. Safety and Efficacy of Transarterial Radioembolisation in Patients with Intermediate or Advanced Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma Refractory to Chemoembolisation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017;40:1882-1890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Malagari K, Chatzimichael K, Alexopoulou E, Kelekis A, Hall B, Dourakis S, Delis S, Gouliamos A, Kelekis D. Transarterial chemoembolization of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: results of an open-label study of 62 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:269-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chung JW, Park JH, Han JK, Choi BI, Han MC, Lee HS, Kim CY. Hepatic tumors: predisposing factors for complications of transcatheter oily chemoembolization. Radiology. 1996;198:33-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Song SY, Chung JW, Han JK, Lim HG, Koh YH, Park JH, Lee HS, Kim CY. Liver abscess after transcatheter oily chemoembolization for hepatic tumors: incidence, predisposing factors, and clinical outcome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:313-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | 21 Kim HK, Chung YH, Song BC, Yang SH, Yoon HK, Yu E, Sung KB, Lee YS, Lee SG, Suh DJ. Ischemic bile duct injury as a serious complication after transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:423-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | 22 Lim EJ, Spanger M, Lubel JS. Gallbladder perforation following transarterial chemoembolisation; a rare but serious complication. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2013;4:135-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Biselli M, Forti P, Mucci F, Foschi FG, Marsigli L, Caputo F, Ravaglia G, Bernardi M, Stefanini GF. Chemoembolization versus chemotherapy in elderly patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma and contrast uptake as prognostic factor. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M305-M309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | 24 Zhang XF, Lai EC, Kang XY, Qian HH, Zhou YM, Shi LH, Shen F, Yang YF, Zhang Y, Lau WY, Wu MC, Yin ZF. Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive fraction of alpha-fetoprotein as a marker of prognosis and a monitor of recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative liver resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2218-2223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Asazawa H, Kamada Y, Takeda Y, Takamatsu S, Shinzaki S, Kim Y, Nezu R, Kuzushita N, Mita E, Kato M, Miyoshi E. Serum fucosylated haptoglobin in chronic liver diseases as a potential biomarker of hepatocellular carcinoma development. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53:95-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Malagari K, Alexopoulou E, Chatzimichail K, Hall B, Koskinas J, Ryan S, Gallardo E, Kelekis A, Gouliamos A, Kelekis D. Transcatheter chemoembolization in the treatment of HCC in patients not eligible for curative treatments: midterm results of doxorubicin-loaded DC bead. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:512-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pietrosi G, Miraglia R, Luca A, Vizzini GB, Fili' D, Riccardo V, D'Antoni A, Petridis I, Maruzzelli L, Biondo D, Gridelli B. Arterial chemoembolization/embolization and early complications after hepatocellular carcinoma treatment: a safe standardized protocol in selected patients with Child class A and B cirrhosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:896-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jones MW, Hannoodee S, Young M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Gallbladder. 2022 Oct 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Monier A, Guiu B, Duran R, Aho S, Bize P, Deltenre P, Dunet V, Denys A. Liver and biliary damages following transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison between drug-eluting beads and lipiodol emulsion. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:1431-1439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tarazov PG, Polysalov VN, Prozorovskij KV, Grishchenkova IV, Rozengauz EV. Ischemic complications of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in liver malignancies. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:156-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wagnetz U, Jaskolka J, Yang P, Jhaveri KS. Acute ischemic cholecystitis after transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma: incidence and clinical outcome. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010;34:348-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kuroda C, Iwasaki M, Tanaka T, Tokunaga K, Hori S, Yoshioka H, Nakamura H, Sakurai M, Okamura J. Gallbladder infarction following hepatic transcatheter arterial embolization. Angiographic study. Radiology. 1983;149:85-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |