Published online Mar 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i3.99124

Revised: November 12, 2024

Accepted: December 25, 2024

Published online: March 15, 2025

Processing time: 214 Days and 23.8 Hours

Colorectal cancer, one of the most common malignancies, is primarily treated through surgery. With the widespread use of laparoscopy, gastrointestinal re

To investigate the safety and short-term outcomes of IISSA with hand-sewn closure of the common opening compared to EA.

Patients who underwent laparoscopic radical colon cancer surgery between January 2018 and June 2022 at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University were retrospectively analyzed. Surgical, postoperative, and pathological features of the IA and EA groups were observed before and after propensity score matching. Patients with right-sided and left-sided colon cancer were separated, each further divided into IA and EA groups (R-IA vs R-EA for right-sided, L-IA vs L-EA for left-sided), for stratified analysis of the aforementioned indicators.

After propensity score matching, 63 pairs were matched in each group. In surgical characteristics, the IA group exhibited less blood loss and shorter incisions than the EA group. Regarding postoperative recovery, the IA group showed earlier recovery of gastrointestinal function. Pathologically, the IA group had greater lymph node clearance. Relative to the R-EA group, the R-IA group experienced reduced blood loss, shorter assisted incisions, earlier recovery of gastrointestinal functions and greater lymph node dissection. When compared to the L-EA group, the L-IA group demonstrated earlier postoperative anal exhaust and defecation, along with a reduced length of hospitalization. Regarding postoperative complications, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups either after matching or in the stratified analyses.

Compared to EA, IISSA with hand-sewn closure of the common opening is a safe and feasible option for laparoscopic radical colon cancer surgery.

Core Tip: This is a study to verify the safety and short-term outcomes of intraperitoneal isoperistaltic side-to-side anastomosis with hand-sewn closure of the common opening in laparoscopic radical resection of colon cancer by comparing with extraperitoneal anastomosis. The results confirmed that intraperitoneal isoperistaltic side-to-side anastomosis with hand-sewn closure of the common opening had better short-term efficacy under the premise of ensuring safety. This study provides a reliable method of digestive tract reconstruction for colon cancer radical resection.

- Citation: Wu B, Zhu JT, Lin HX, Dai YH, Lin TS, Huang AL, Chen YN, Li YW, Wang HB, Chen YF, Chen DH, Yu HD, You J, Hong QQ. Is intraperitoneal isoperistaltic side-to-side anastomosis a safe surgical procedure in radical colon cancer surgery. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(3): 99124

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i3/99124.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i3.99124

According to the Global Cancer Statistics 2020, colorectal cancer represents 10% of all cancer cases, ranking as the third most common cancer[1]. Currently, surgery remains the primary treatment approach for colon cancer. Laparoscopic techniques are now well-established and widely used in colon cancer treatment. Anastomosis with staplers in the extraperitoneal cavity currently forms the cornerstone of gastrointestinal reconstruction in laparoscopic radical colon cancer surgery. However, this method requires a long auxiliary incision and poses risks such as considerable post

In this study, we collected data from patients who underwent laparoscopic radical colon cancer surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University between January 2018 and June 2022. Out of the total, 336 cases were selected for the study, divided into two groups: The IA group (n = 70) with IISSA, and the extraperitoneal anastomosis (EA) group (n = 266) without this procedure. This study was approved and registered by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, with approval number: [2023] Scientific Research Ethics Review No. 005.

The inclusion criteria are: (1) Age between 18 and 80 years; (2) Preoperative pathological biopsy confirming colon cancer without evidence of distant metastasis; (3) Absence of preoperative local complications, including obstruction, massive active bleeding, perforation, abscess formation, and invasion of adjacent organ tissues; (4) No concurrent multiple primary malignancies; and (5) No preoperative neoadjuvant therapy.

The exclusion criteria are: (1) History of previous surgery for colorectal malignancy; (2) Emergency surgery for bowel obstruction, perforation, or bleeding; (3) Primary tumor invasion into the abdominal wall and/or adjacent organs; (4) Presence of multiple primary tumors; (5) Women who are pregnant or lactating; and (6) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) performance status of grade IV or higher and/or the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group physical status of 2 or higher.

Clinical characteristics include gender, age, body mass index (BMI), ASA performance status, comorbidities, and tumor location. Surgery-related indicators encompass operation duration, blood loss, anastomotic techniques, and size of the auxiliary incision. Pathologic outcomes include tumor size, gross and histological types, pathological T and N stages, number of lymph nodes removed, neurovascular invasion, and surgical margins. Post-operative recovery metrics cover time to flatus, defecation and feeding, duration of abdominal drainage tube retention, length of postoperative hospital stay, and complications.

All postoperative complications are categorized using the Clavien-Dindo classification, with only those of grade 2 or higher included in this study. Diagnostic criteria for paralytic intestinal obstruction include no flatus or defecation for 4 or more days post-surgery, accompanied by optional symptoms of abdominal distension, pain, and vomiting. Chyle leak diagnosis involves no decrease in the amount of drainage fluid for 48 hours, presence of chyle-like material in the drainage, and a positive chyle test for confirmation. Postoperative intra-abdominal infections, categorized as surgical site infections, are diagnosed based on clinical symptoms within 30 days post-surgery and confirmed through drainage fluid analysis or examination. Pulmonary infection diagnosis requires substantial lung inflammation from bacterial, fungal, or other pathogens within 2 weeks post-surgery, confirmed via imaging or bacteriological tests. Anastomotic leak is diagnosed by sudden fever with peritonitis signs post-surgery, purulent or fecal-like discharge from the anus or drainage tube, fluid or gas near the anastomosis on computed tomography, or a positive Melan test. Incision-related complications, such as bleeding, infection, and poor healing, are identified by redness, swelling, warmth, pain, or purulent discharge at the incision site within 30 days post-surgery, confirmed through bacteriological examination.

All patients receive an oral magnesium sulphate solution for standardized bowel preparation the day before the procedure. Prophylactic antibiotics are administered 1 hour before surgery, then every 3 hours during the operation, and continued postoperatively for up to 48 hours. Postoperative analgesia is administered for 1 to 2 days. The resumption of eating is determined by the recovery of gastrointestinal function post-surgery, assessed based on the time to flatus and bowel movements. Patients are discharged once they can tolerate food.

Surgical steps include: (1) Establish and maintain an artificial CO2 pneumoperitoneum at 13 mmHg; (2) Trocar positions follow the conventional five-hole method, with placement tailored to the tumor’s location; (3) Perform D3 radical surgery, including exploration, lymph node dissection, and resection of the primary site, as per the Japanese Classification of Colorectal, Appendiceal, and Anal Carcinoma; and (4) The IA group employs isoperistaltic side-to-side anastomosis, while the EA group uses end-to-end, end-to-side, or side-to-side anastomosis based on the surgeon’s preference and patient’s condition.

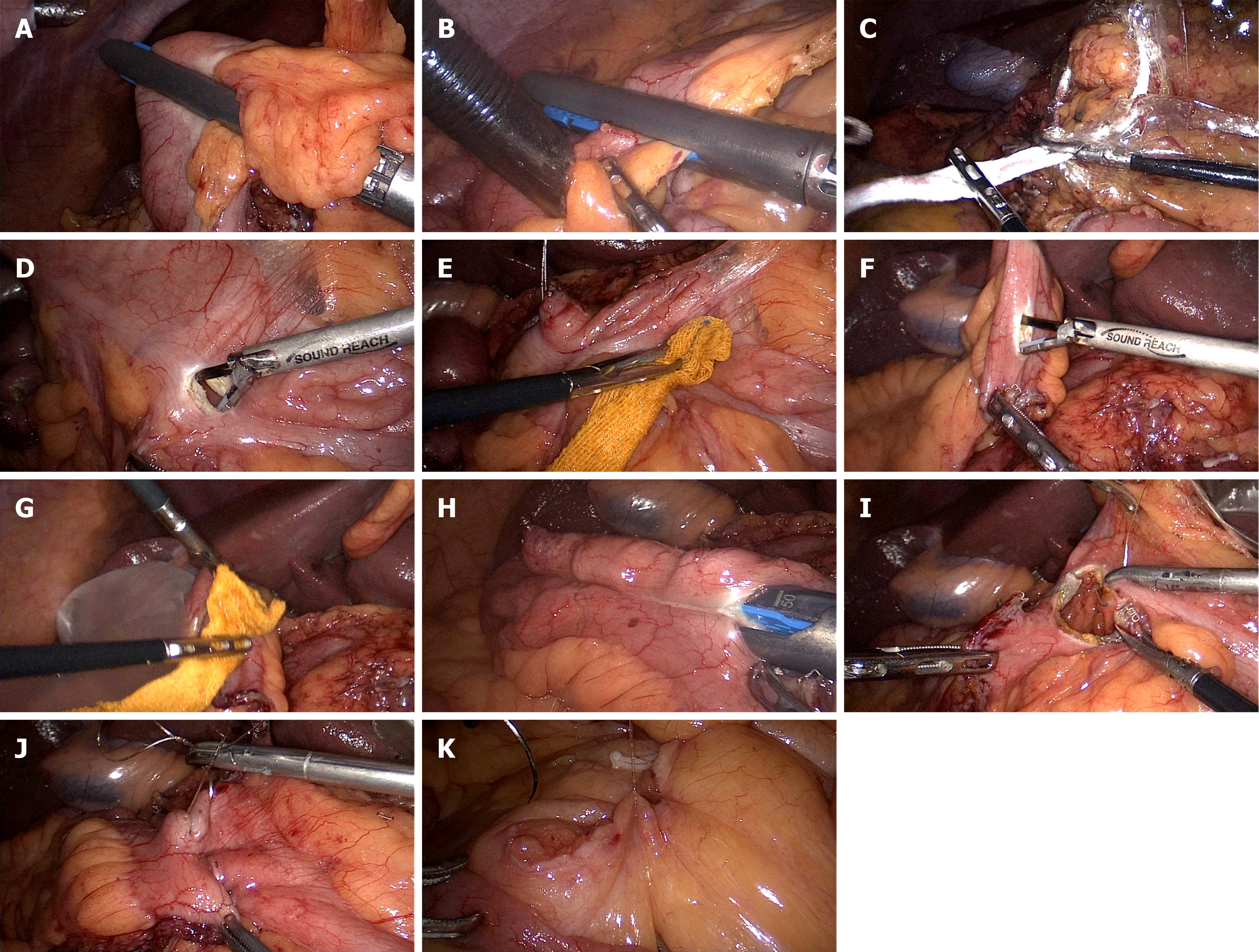

For IISSA, start by closing and disconnecting the intestinal canal using a 60 mm linear cutter at the planned resection site (Figure 1A and B). Place the specimen in a bag (Figure 1C) and position it in the pelvis. Next, align the proximal and distal intestinal segments in an isoperistaltic manner. Create two small holes, each about the size of an ultrasound tip, using an ultrasonic knife 2 cm from the proximal and 8 cm from the distal segment, opposite the mesenteric margin. Disinfect these holes with iodophor-soaked gauze (Figure 1D-G), then place them in a specimen bag. Insert a 60 mm linear cutter into both the distal and proximal holes. Clamp the intestinal wall opposite the mesentery to perform the anastomosis (Figure 1H). A continuous suture (mid-point suture) using a 4-0 barbed suture is performed on the entire intestinal layer of the common opening, encapsulating, and reinforcing the serous and muscle layers (Figure 1I and J). Reinforce and embed both the distal and proximal intestinal breaks. Finally, close the mesenteric fissure with a 4-0 barbed suture (Figure 1K). Enlarge the navel observation hole to about 3 cm, adjustable based on tumor size, and remove the specimen bag under an incision protector after accessing the abdomen in layers. Complete the digestive tract reconstruction.

For the mid-point suture, identify the two endpoints A and B, and midpoints M1 and M2 of the common opening. The surgeon and assistant apply tension to the AB points of the common opening. Next, suture from point M1 to M2 using a 4-0 barbed thread. This step forms two smaller common openings. Then, suture from point M to A, sealing one side of the opening, and return to M to encase the unilateral plasma membrane and muscle layers. Repeat this procedure for the other side of the opening. Close the auxiliary incision and trocar holes, leaving 1-2 drainage tubes in the intra-abdominal cavity. Conclude the procedure.

To minimize selective bias and balance confounding factors’ effects on short-term postoperative outcomes, we employed a logistic regression model for propensity score matching. Dependent variables comprised gender, age, ASA performance status, comorbidities, and tumor location. Using a caliper value of 0.02 and a 1:1 matching ratio, we successfully matched 63 pairs. Data were compared before and after matching both sets. Measurements with normal distribution are presented as mean ± SD, with t-tests used for intergroup comparisons. Measurements with skewed distribution are expressed as M(Q), compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. Statistical data are reported as rates, with the χ2-test employed for intergroup comparisons. A P value of < 0.05 is considered statistically significant for differences between the two groups.

Recognizing the anatomical and oncological differences between the left and right colon, we segregated the matched patients into left and right groups. Furthermore, to mitigate the impact of these differences on our results, we conducted separate statistical analyses on their intraoperative and postoperative data.

Before matching, there were 70 patients in the IA group and 266 in the EA group. The difference in tumor site between the groups was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Other factors, such as age (60.86 ± 11.79 years vs 59.72 ± 11.97 years, P = 0.479), gender (P = 0.266), BMI (22.40 ± 2.60 kg/m2vs 22.92 ± 3.08 kg/m2, P = 0.194), ASA performance status (P = 0.762), and comorbidities (P = 1.000), showed no significant differences between the groups. After matching, both the IA and EA groups had 63 cases each, with an equal distribution of tumor cases at each site: 7 in the ileocecal, 26 in the ascending colon, 18 in the transverse colon, 11 in the descending colon, and 1 in the sigmoid colon. Post-matching, the differences in clinical characteristics were not statistically significant (P > 0.050). Clinical characteristics before and after matching are detailed in Table 1.

| Before matching, IA (n = 70) | Before matching, EA (n = 266) | Before matching, P value | After matching, IA (n = 63) | After matching, EA (n = 63) | After matching, P value | |

| Sex | 0.266 | 0.372 | ||||

| Male | 34 (48.6) | 149 (56) | 32 (50.8) | 27 (42.9) | ||

| Female | 36 (51.4) | 117 (44) | 31 (49.2) | 36 (57.1) | ||

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 60.86 ± 11.79 | 59.72 ± 11.97 | 0.479 | 61.33 ± 11.56 | 60.52 ± 11.35 | 0.638 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 22.40 ± 2.60 | 22.92 ± 3.08 | 0.194 | 22.58 ± 2.60 | 22.93 ± 2.66 | 0.481 |

| ASA score | 0.762 | 0.433 | ||||

| 2 | 66 (94.3) | 245 (92.1) | 59 (93.7) | 60 (95.2) | ||

| 3 | 4 (5.7) | 20 (7.5) | 4 (6.3) | 2 (3.2) | ||

| 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | ||

| Comorbidity | 1.000 | 0.854 | ||||

| None | 45 (64.3) | 171 (64.3) | 39 (61.9) | 40 (63.5) | ||

| Yes | 25 (35.7) | 95 (35.7) | 24 (38.1) | 23 (36.5) | ||

| Tumor site | < 0.001 | 1.000 | ||||

| Ileocecum | 8 (11.4) | 14 (5.3) | 7 (11.1) | 7 (11.1) | ||

| Ascending colon | 26 (37.2) | 61 (22.9) | 26 (41.3) | 26 (41.3) | ||

| Transverse colon | 24 (34.3) | 21 (7.9) | 18 (28.5) | 18 (28.5) | ||

| Descending colon | 11 (15.7) | 43 (16.2) | 11 (17.5) | 11 (17.5) | ||

| Sigmoid | 1 (1.4) | 103 (38.7) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.6) | ||

| Upper rectum | 0 (0) | 24 (9.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Surgical characteristics remained consistent before and after matching. After matching, the IA group exhibited a longer operative time (194 ± 47.04 minutes vs 219.11 ± 43.04 minutes, P = 0.001) than the EA group, but with less blood loss (56.19 ± 36.21 mL vs 84.76 ± 63.45 mL, P = 0.02) and smaller incision size (3.49 ± 0.83 cm vs 5.63 ± 1.32 cm, P < 0.001). Surgical characteristics before and after matching are detailed in Table 2.

| Before matching, IA (n = 70) | Before matching, EA (n = 266) | Before matching, P value | After matching, IA (n = 63) | After matching, EA (n = 63) | After matching, P value | |

| Operation time, minutes | 217.47 ± 43.33 | 177.17 ± 46.04 | < 0.001 | 219.11 ± 43.04 | 194.00 ± 47.04 | 0.001 |

| Blood loss, mL | 55.29 ± 35.21 | 71.88 ± 55.99 | 0.010 | 56.19 ± 36.21 | 84.76 ± 63.45 | 0.002 |

| Incision size, cm | 3.57 ± 0.97 | 5.48 ± 1.16 | < 0.001 | 3.49 ± 0.83 | 5.63 ± 1.32 | < 0.001 |

Before matching, the IA group had a shorter postoperative hospital stay compared to the EA group, a statistically significant difference (10.64 ± 4.05 days vs 12.13 ± 6.21 days, P = 0.030). After matching, the IA group continued to have a shorter postoperative hospital stay, though the difference diminished (10.92 ± 4.18 days vs 11.97 ± 5.31 days, P = 0.124). Additionally, both before and after matching, the IA group showed shorter times to flatus, defecation, feeding, and drainage tube retention compared to the EA group (P < 0.05). The incidence of postoperative complications was comparable between the groups (19.0% vs 22.2%, P = 0.660). Postoperative characteristics before and after matching are detailed in Table 3.

| Before matching, IA (n = 70) | Before matching, EA (n = 266) | Before matching, P value | After matching, IA (n = 63) | After matching, EA (n = 63) | After matching, P value | |

| Exhaust time, days | 3.21 ± 1.19 | 4.79 ± 1.84 | < 0.001 | 3.22 ± 1.24 | 4.86 ± 1.62 | < 0.001 |

| Defecation time, days | 6.67 ± 1.59 | 8.26 ± 2.60 | < 0.001 | 6.70 ± 1.64 | 8.17 ± 1.72 | < 0.001 |

| Eating time, days | 4.33 ± 1.61 | 5.52 ± 1.94 | < 0.001 | 4.38 ± 1.68 | 5.57 ± 1.71 | < 0.001 |

| Peritoneal drainage time, days | 8.11 ± 2.72 | 10.62 ± 7.32 | 0.003 | 8.24 ± 2.83 | 9.95 ± 3.26 | 0.002 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, days | 10.64 ± 4.05 | 12.13 ± 6.21 | 0.030 | 10.92 ± 4.18 | 11.97 ± 5.31 | 0.124 |

| Complication, n (%) | 0.273 | 0.660 | ||||

| Yes | 13 (18.6) | 66 (24.8) | 12 (19.0) | 14 (22.2) | ||

| No | 57 (81.4) | 200 (75.2) | 51 (81.0) | 49 (77.8) |

The overall rate of postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo classification ≥ 2) was 19.0% in the IA group and 22.2% in the EA group, without a statistically significant difference. In the IA group, there were 10 cases of grade II complications and 2 cases of grade III complications. In the EA group, there were 13 cases of grade II complications and 1 case of grade III complications. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups for both levels of complications. Paralytic intestinal obstruction and intra-abdominal infection were evaluated separately. In the IA group, the incidence of paralytic intestinal obstruction was 1.6% and of abdominal infection was 4.8%. In the EA group, these incidences were 9.5% and 1.6% respectively. Nevertheless, these differences were not statistically significant. Table 4 details the postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo classification ≥ 2) for both groups after matching.

| IA (n = 63) | EA (n = 63) | P value | |

| All, n (%) | 12 (19.0) | 14 (22.2) | 0.660 |

| CD2 | 10 | 13 | 0.489 |

| Paralytic ileus | 1 | 6 | 0.052 |

| Anastomotic leak | 1 | 0 | |

| Delayed healing of incision | 1 | 3 | |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 3 | 1 | 0.310 |

| Pneumonia | 2 | 3 | |

| Chyle leak | 2 | 0 | |

| CD3 | 2 | 1 | 0.559 |

| Incisional infections | 2 | 1 |

The IA group had more lymph nodes cleared than the EA group, a significant difference both before and after matching (Before: 34.71 ± 16.21 vs 26.29 ± 12.35, P < 0.001; After: 33.51 ± 15.86 vs 28.71 ± 11.91, P = 0.031). After matching, differences in tumor size (4.29 ± 1.79 mm vs 4.11 ± 1.82 mm, P = 0.587), gross type (P = 0.202), histological type (P = 0.405), T-stage (P = 0.291), N-stage (P = 0.137), neurovascular invasion (P = 1.000), and cut margin status (P = 1.000) were not statistically significant between the groups. Pathological features before and after matching are detailed in Table 5.

| Before matching, IA (n = 70) | Before matching, EA (n = 266) | Before matching, P value | After matching, IA (n = 63) | After matching, EA (n = 63) | After matching, P value | |

| Tumor size, mm (mean ± SD) | 4.32 ± 1.74 | 4.15 ± 1.78 | 0.463 | 4.29 ± 1.79 | 4.11 ± 1.82 | 0.587 |

| Gross type | 0.871 | 0.202 | ||||

| Protuberant type | 33 (47.1) | 129 (48.5) | 27 (42.8) | 34 (54.0) | ||

| Ulcerative type | 35 (50.0) | 132 (49.6) | 34 (54.0) | 29 (46.0) | ||

| Infiltrative type | 2 (2.9) | 5 (1.9) | 2 (3.2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Histological type | 0.599 | 0.405 | ||||

| Well | 3 (4.3) | 12 (4.5) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (3.2) | ||

| Mod | 58 (82.8) | 197 (74.1) | 54 (85.7) | 47 (74.6) | ||

| Por | 7 (10.0) | 44 (16.5) | 5 (7.9) | 9 (14.3) | ||

| Muc | 2 (2.9) | 12 (4.5) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (7.9) | ||

| Else | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Pathological T status | 0.568 | 0.291 | ||||

| Tis | 3 (4.3) | 4 (1.5) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (3.2) | ||

| 1 | 7 (10.0) | 27 (10.2) | 7 (11.1) | 5 (7.9) | ||

| 2 | 6 (8.6) | 32 (12.0) | 5 (7.9) | 6 (9.5) | ||

| 3 | 36 (51.4) | 120 (45.1) | 32 (50.8) | 22 (34.9) | ||

| 4a | 18 (25.7) | 82 (30.8) | 17 (27.0) | 28 (44.5) | ||

| 4b | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Cleared lymph nodes (mean ± SD) | 34.71 ± 16.21 | 26.29 ± 12.35 | < 0.001 | 33.51 ± 1.86 | 28.71 ± 11.91 | 0.031 |

| Pathological N status | 0.253 | 0.137 | ||||

| 0 | 38 (54.3) | 171 (64.3) | 32 (50.8) | 43 (68.3) | ||

| 1a | 16 (22.9) | 32 (12.4) | 16 (25.4) | 9 (14.3) | ||

| 1b | 8 (11.4) | 24 (9.0) | 8 (12.7) | 6 (9.5) | ||

| 1c | 0 (0) | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| 2a | 5 (7.1) | 23 (8.6) | 4 (6.3) | 5 (7.9) | ||

| 2b | 3 (4.3) | 11 (4.2) | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Neurovascular invasion | 0.910 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 30 (42.9) | 112 (42.1) | 26 (41.3) | 26 (41.3) | ||

| No | 40 (57.1) | 154 (57.9) | 37 (58.7) | 37 (58.7) | ||

| Surgical margin | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Positive | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Negative | 70 (100) | 266 (100) | 63 (100) | 63 (100) |

The entire cohort was divided based on tumor location into the left-side group (n = 32) and the right-side group (n = 94). Results for the right-side group (R-IA = 47, R-EA = 47) were similar to the overall findings. Within the left-side group (L-IA = 47, L-EA = 47), the L-IA group experienced a shorter postoperative hospital stay than the L-EA group, with no significant differences in blood loss, operative time, time to postoperative feeding and drainage tube retention, or lymph node dissection. Tables 6 and 7 detail the results for the right-side and left-side groups following stratified analysis.

| R-IA (n = 47) | R-EA (n = 47) | P value | |

| Age, years | 62.32 ± 10.55 | 60.19 ± 11.97 | 0.363 |

| Sex, n (%) | 1.000 | ||

| Male | 22 (46.8) | 22 (46.8) | |

| Female | 25 (53.2) | 25 (53.2) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.69 ± 2.38 | 5.66 ± 1.83 | 0.777 |

| Incision size, cm | 3.65 ± 0.85 | 5.72 ± 1.41 | < 0.001 |

| Blood loss, mL | 55.96 ± 34.56 | 88.09 ± 68.45 | 0.005 |

| Operation time, hours | 226.06 ± 40.48 | 193.57 ± 44.68 | < 0.001 |

| Exhaust time, days | 3.15 ± 1.32 | 4.94 ± 1.75 | < 0.001 |

| Defecation time, days | 6.81 ± 1.61 | 8.19 ± 1.81 | < 0.001 |

| Eating time, days | 4.38 ± 1.71 | 5.66 ± 1.83 | 0.001 |

| Peritoneal drainage time, days | 8.15 ± 3.07 | 9.98 ± 3.44 | 0.008 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, days | 11.26 ± 4.55 | 11.63 ± 5.43 | 0.712 |

| Cleared lymph nodes | 37.15 ± 14.17 | 29.74 ± 11.11 | 0.006 |

| Complication, n (%) | 0.797 | ||

| Yes | 10 (21.3) | 9 (19.1) | |

| No | 37 (78.7) | 38 (80.9) |

| L-IA (n = 16) | L-EA (n = 16) | P value | |

| Age, years | 58.44 ± 14.1 | 61.50 ± 9.57 | 0.478 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.077 | ||

| Male | 10 (62.5) | 5 (68.7) | |

| Female | 6 (37.5) | 11 (31.3) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.23 ± 3.21 | 23.21 ± 2.90 | 0.370 |

| Incision size, cm | 3.03 ± 0.53 | 5.38 ± 1.02 | < 0.001 |

| Blood loss, mL | 56.88 ± 41.91 | 75.00 ± 46.19 | 0.254 |

| Operation time, hours | 198.69 ± 45.12 | 196.56 ± 54.95 | 0.254 |

| Exhaust time, days | 3.44 ± 0.96 | 4.63 ± 1.15 | 0.004 |

| Defecation time, days | 6.38 ± 1.75 | 8.13 ± 1.45 | 0.004 |

| Eating time, days | 4.38 ± 1.63 | 5.31 ± 1.30 | 0.082 |

| Peritoneal drainage time, days | 8.50 ± 2.03 | 9.88 ± 2.78 | 0.121 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, days | 9.94 ± 2.72 | 12.94 ± 5.00 | 0.046 |

| Cleared lymph nodes | 22.81 ± 11.14 | 25.69 ± 13.94 | 0.524 |

| Complication, n (%) | 0.200 | ||

| Yes | 2 (12.5) | 5 (31.3) | |

| No | 14 (87.5) | 11 (68.7) |

This study applied propensity score matching to examine the safety and short-term outcomes of IA in radical colon cancer surgery. After matching, the influence of tumor site on baseline variables was neutralized. It was found that IISSA with hand-sewn closure of the common opening shortened postoperative recovery time while ensuring tumor eradication and surgical safety. Regarding surgical metrics, the IA group showed advantages in blood loss and incision length over the EA group, albeit with a longer operative time. Stratified analysis revealed that these differences were more pronounced in the right-side group. Conclusions regarding operation times are corroborated by most studies[2-4], though a few found no significant differences[5,6]. In the left-side group, no significant differences in blood loss or operative time were noted between the two procedures, with the exception of a smaller assisted incision in the IA-L group. Similar findings were reported in the study by Wang et al[7]. We hypothesize that the difference in operative time between the IA and EA groups in this study is primarily due to gastrointestinal reconstruction. For anastomotic reinforcement, the EA group used conventional surgical instruments under direct vision, whereas the IA group required laparoscopic instruments, which increased procedural difficulty and slowed suturing speed, thereby extending the operative time. In the stratified analysis, the left-sided group primarily involved colo-colonic anastomosis, where L-EA required mobilization of a longer segment of intestine, whereas L-IA saved time by bypassing this step, thereby reducing the time difference during anastomotic reinforcement. In right-sided group, primarily involving ileocolonic anastomosis, neither R-EA nor R-IA required further mobilization of the ileum. Due to the larger proportion of the right-sided group in the study, the IA group showed longer operative times. In terms of postoperative recovery indicators, the IA group demonstrated superior short-term outcomes, including shorter times for postoperative flatus, defecation, eating, and drainage tube retention. These results align closely with those of a previous study[8]. Notably, before matching, the IA group had a shorter postoperative hospital stay than the EA group, a difference that disappeared after matching. We hypothesized that this discrepancy might be related to the tumor’s location, a hypothesis confirmed through stratified analysis. In the left-side group, the IA-L group had a shorter length of stay compared to the EA-L group, while in the right-side group, there was no significant difference. These findings are consistent with those reported by Sakurai et al[4], for right hemicolectomy and Grieco et al[9] for left hemicolectomy[7,10].

Regarding postoperative complications, the overall incidence was comparable between the two groups, aligning with findings from most academic studies[11,12]. However, the EA group exhibited higher odds of paralytic intestinal obstruction (9.25% vs 1.59%, P = 0.052). This is consistent with the findings of Kim et al[13]. Conversely, the IA group had higher odds of intra-abdominal infection (4.76% vs 1.59%, P = 0.559). Even though the difference between the two complication rates is not statistically significant, we can still subjectively assume that there is some bias in the type of complications between the two different procedures. The likely reasons for these differences are thought to relate mainly to the anastomosis position and the anastomotic device type. Given that the IA group’s anastomosis occurs within the abdominal cavity and takes longer, this may facilitate bacterial migration during anastomosis, raising the likelihood of postoperative intra-abdominal infection. To reduce the incidence of such infections, we recommend: (1) Thorough preoperative gastrointestinal preparation with enemas or oral laxatives to clear intestinal contents; (2) Standardized perioperative prophylactic antibiotic use; (3) Adequate pre-anastomosis disinfection and minimizing unnecessary manipulation; (4) In case of accidental intraoperative bowel content spillage, immediate aspiration and disinfection are necessary, followed by adequate flushing of the abdominal cavity; and (5) Improved laparoscopic anastomosis techniques to shorten exposure time. In the EA group, a portion of the cases involve end-to-side anastomoses, where post-reconstruction, both the anastomotic area and line length are significantly smaller compared to side-to-side anastomosis. We suspect that the improved postoperative blood supply and wider anastomosis in IA contribute to earlier bowel function recovery and a reduced incidence of paralytic bowel obstruction.

In terms of postoperative pathology, IA resulted in a higher lymph node yield compared to EA. However, this difference was not statistically significant within the left-side group. Other studies have less frequently observed this phenomenon[4,9,14]. Nonetheless, it cannot be denied that IA may enhance the radicality of hemicolectomy. The number of lymph nodes dissected is associated with the effectiveness of tumor eradication, as thorough dissection can potentially reduce recurrence risk by eliminating potential cancer cell spread pathways, thereby improving postoperative survival rates. Additionally, a higher lymph node dissection count may contribute to more accurate tumor staging and provide valuable insights for determining appropriate postoperative adjuvant therapy.

In this study, we conducted IISSA in the IA group, closing the common opening with hand-sewn sutures. The midpoint suture method was primarily used for closing the common opening. The primary advantages of this anastomosis technique include: (1) It minimizes intestinal mobilization and preserves blood supply, thereby reducing the assisted abdominal incision length, enhancing aesthetics, and lessening postoperative pain; (2) Earlier gastrointestinal recovery, as previously discussed; and (3) Midpoint hand stitching for closing the common opening avoids challenges associated with uneven lengths. This approach, compared to linear cutting closures, reduces the number of anastomoses used, lowering patient costs and the likelihood of anastomotic stricture, thus decreasing postoperative bowel obstruction risk. However, manual suturing demands high proficiency in laparoscopic suturing and is more time-consuming. Our study has some limitations: (1) Being retrospective in nature, despite employing propensity score matching, selective bias was inevitable; and (2) The distribution of tumor cases across different colon cancer sites was unequal. Even with 1:1 matching, the sample size for left hemicolectomy remained smaller than that for the right.

Compared to the EA group, the IA group demonstrated superior immediate postoperative outcomes without an increased rate of postoperative complications. IISSA with hand-sewn closure of the common opening is a safe and feasible approach in radical colon cancer surgery.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64637] [Article Influence: 16159.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (176)] |

| 2. | Liao CK, Chern YJ, Lin YC, Hsu YJ, Chiang JM, Tsai WS, Hsieh PS, Hung HY, Yeh CY, You JF. Short- and medium-term outcomes of intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic right colectomy: a propensity score-matched study. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shapiro R, Keler U, Segev L, Sarna S, Hatib K, Hazzan D. Laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with intracorporeal anastomosis: short- and long-term benefits in comparison with extracorporeal anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3823-3829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sakurai T, Yamaguchi T, Noguchi T, Sakamoto T, Mukai T, Hiyoshi Y, Nagasaki T, Akiyoshi T, Fukunaga Y. Short-term outcomes of intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic surgery for right-sided colon cancer: A propensity score-matched study. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2023;16:14-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Małczak P, Wysocki M, Pisarska-Adamczyk M, Major P, Pędziwiatr M. Bowel function after laparoscopic right hemicolectomy: a randomized controlled trial comparing intracorporeal anastomosis and extracorporeal anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:4977-4982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Scatizzi M, Kröning KC, Borrelli A, Andan G, Lenzi E, Feroci F. Extracorporeal versus intracorporeal anastomosis after laparoscopic right colectomy for cancer: a case-control study. World J Surg. 2010;34:2902-2908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang LM, Jong BK, Liao CK, Kou YT, Chern YJ, Hsu YJ, Hsieh PS, Tsai WS, You JF. Comparison of short-term and medium-term outcomes between intracorporeal anastomosis and extracorporeal anastomosis for laparoscopic left hemicolectomy. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brown RF, Cleary RK. Intracorporeal anastomosis versus extracorporeal anastomosis for minimally invasive colectomy. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;11:500-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Grieco M, Cassini D, Spoletini D, Soligo E, Grattarola E, Baldazzi G, Testa S, Carlini M. Intracorporeal Versus Extracorporeal Anastomosis for Laparoscopic Resection of the Splenic Flexure Colon Cancer: A Multicenter Propensity Score Analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2019;29:483-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Swaid F, Sroka G, Madi H, Shteinberg D, Somri M, Matter I. Totally laparoscopic versus laparoscopic-assisted left colectomy for cancer: a retrospective review. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2481-2488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Biondi A, Santocchi P, Pennestrì F, Santullo F, D'Ugo D, Persiani R. Totally laparoscopic right colectomy versus laparoscopically assisted right colectomy: a propensity score analysis. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:5275-5282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ozawa H, Sakamoto J, Nakanishi H, Fujita S. Short-term outcomes of intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis after laparoscopic colectomy: a propensity score-matched cohort study from a single institution. Surg Today. 2022;52:616-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim IY, Cho MY, Kim YW. Synchronous multiple colonic adenocarcinomas arising in patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2014;87:156-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hamamoto H, Suzuki Y, Takano Y, Kuramoto T, Ishii M, Osumi W, Masubuchi S, Tanaka K, Uchiyama K. Medium-term oncological outcomes of totally laparoscopic colectomy with intracorporeal anastomosis for right-sided and left-sided colon cancer: propensity score matching analysis. BMC Surg. 2022;22:345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |